Abstract

The high incidence of de novo chromosomal aberrations in a population of persons with autism suggests a causal relationship between certain chromosomal aberrations and the occurrence of isolated idiopathic autism. We report on the clinical and cytogenetic findings in a male patient with autism, no physical abnormalities and a de novo balanced (7;16)(p22.1;p16.2) translocation. G-banded chromosomes and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) were used to examine the patient's karyotype as well as his parents'. FISH with specific RP11-BAC clones mapping near 7p22.1 and 16p11.2 was used to refine the location of the breakpoints. This is, in the best of our knowledge, the first report of an individual with autism and this specific chromosomal aberration.

1. INTRODUCTION

Autism is a relatively common and heterogeneous neuropsychiatric disorder characterised by reduced social and interindividual contacts and interactions. Autism usually starts in early childhood. Complete absence of eye contact and speech can be observed in severe forms of autism [1]. Its incidence is estimated at about 1/1000 to 1/2000 with a biased male-to-female ratio of three or four to one (3-4 : 1) [2]. Studies of familial cases have demonstrated that genetic factors are involved in the aetiology of autism [3]. A number of balanced and unbalanced chromosomal aberrations have been found to be associated with autism [4–6].

In this study, we describe a reciprocal translocation t(7;16)(p22.1;p11.2) that occurred de novo in a 10-year-old boy with autism and psychomotor retardation and only minor additional anomalies or dysmorphic features. Neither chromosomal breakpoint has been mentioned in previous reports of cytogenetic aberrations seen in patients with autistic behaviour.

2. CASE REPORT

The 10-year-old patient is the younger of two children born at term from nonconsanguineous healthy parents. The father and the mother were, respectively, 34 and 30 years old when the child was born. Pregnancy was uneventful. Delivery was by caesarean section secondary to a narrow basin. Birth weight was 3350 kg, and no recognized malformations were noted. His older sister is healthy and developmentally normal.

Patient's psychomotor delays were noticed in the first months of life by his parents; they also reported frequent crying and sleep disturbances. He was unable to maintain eye contact and presented many motor stereotypes and ritualistic behaviours such as cutting papers into small pieces and aligning objects. Clinical assessment showed a boy with no dysmorphic signs (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The phenotype of the patient.

At the age of 4 years and 11 months, the patient was examined by an experienced child psychiatrist who found impairments in social interaction and communication according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-revision 4 (DSM-IV) and the Autism Diagnostic Interview (ADI-R), French version 1993, criteria and made the clinical diagnosis of autism.

Routine hearing tests and amino acid chromatography were normal. Brain CT scan revealed a cerebellar megacysterna in the posterior fossa and a temporal arachnoidal cyst. The electroencephalogram was normal. Southern blot analysis revealed the absence of FRAXA mutation.

3. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chromosomal abnormalities have been identified by using traditional cytogenetics and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH).

Chromosomes were prepared from phytohemagglutinin (PHA) stimulated peripheral blood lymphocytes of the proband and his parents following standard procedures. The healthy sister was not available for analysis. All chromosome preparations were G-banded and then analysed.

For FISH analysis, metaphase spreads obtained from an Epstein Barr virus (EBV) immortalised cell line from the patient were hybridised with bacterial artificial chromosome clones (BACs). The RPCI-11 BAC clones covering genomic regions on both chromosomes were selected according to the UCSC Genome browser (http://www.genome.ucsc.edu/) and Ensembl genome database (http://www.ensembl.org/Homo_sapiens/). They were provided by BACPAC resource centre (BPRC) (http://bacpac.chori.org) and professor Mariano Rocchi (University of Bari, Italy). Thesequence limits of the BACs were defined according to DECIPHER database (https://enigma.sanger.ac.uk/perl/PostGenomics/decipher);

BAC clones were biotinylated with biotin-11-dUTP (Sigma) by nick translation using the Bio Nick labelling system (Invitrogen Life Technologies). For the double colour FISH experiment, one probe was labelled with biotin-11-dUTP and the second probe, a commercially one, with Rhodamine (QBiogen).

4. RESULTS

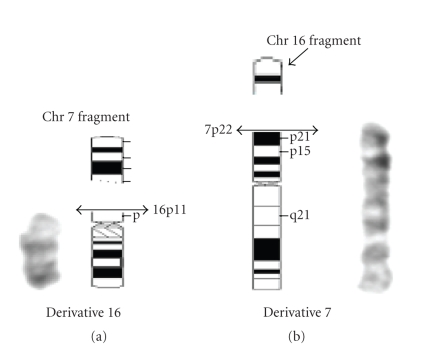

Routine and high-resolution chromosome studies revealed a de novo translocation carried by the proband. The G-band pattern suggested a balanced translocation involving 7p22 and 16p11.2 and established the karyotype as 46,XY,t(7;16)(p22; p11) (see Figure 2). The parent karyotypes were normal. To identify the translocation breakpoints, we used 16 bacterial artificial chromosome clones (BACS) from 7p22 and 16p11 in fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis (see Table 1).

Figure 2.

Partial GTG-banding karyotype of the patient. The patient derivative chromosomes 7 and 16 are shown. By comparing both respective ideogrammed chromosomes, the breakpoints were located in 7p22 and 16p11.2.

Table 1.

FISH results using BAC clones on 7p and 16p regions.

| RP11 clone ID | Map position | Start* | End* | FISH signal on normal chromosome 7 | FISH signal on Derivative 7 | FISH signal on normal chromosome 16 | FISH signal on Derivative 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 368N21 | 16p11.2 | 29408699 | 29609853 | − | + | + | − |

| 261H5 | 16p11.2 | 31120739 | 31307726 | − | + | + | − |

| 120K18 | 16p11.2 | 31163677 | 31329206 | − | + | + | − |

| 264M14 | 16p11.2 | 33282423 | 33452774 | − | + | + | + |

| 341P6 | 16p11.2 | 34263016 | 34452072 | − | + | + | + |

| 104C4 | 16p11.2 | 33362222 | 33555929 | − | − | + | + |

| 488I20 | 16p11.2 | 34359841 | 34490213 | − | − | + | + |

| 449P15 | 7p22.3 | 885103 | 1079306 | + | − | − | + |

| 42B7 | 7p22.2 | 4126462 | 4281105 | + | − | − | + |

| 33P21 | 7p22.1 | 4559141 | 4711177 | + | − | − | + |

| 32P3 | 7p22.1 | 4711178 | 4751000 | + | − | − | + |

| 160E17 | 7p22.1 | 4751001 | 4911018 | + | − | − | + |

| 805D5 | 7p22.1 | 4911019 | 4933256 | + | − | − | + |

| 730B22 | 7p22.1 | 4933257 | 5107654 | + | + | − | + |

| 147A22 | 7p22.1 | 5183822 | 5357984 | + | + | − | − |

| 1275H24 | 7p22.1 | 5427168 | 5510299 | + | + | − | − |

| 425P5 | 7p22.1 | 6233987 | 6446613 | + | + | − | − |

+ : presence of the signal hybridization.

− : absence of the signal hybridization.

* : nucleotide position according to DECIPHER (https://enigma.sanger.ac.uk/perl/PostGenomics/decipher).

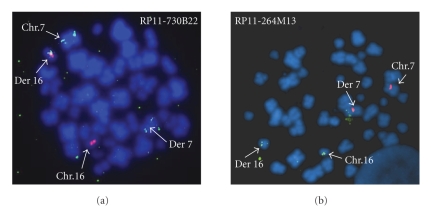

As shown in Figure 3(a), the RP11-730B22 BAC hybridized to both derivative 7 and the derivative 16 and the normal chromosome 7, but not to the normal chromosome 16, indicating that this clone spans the translocation breakpoint on chromosome 7.

Figure 3.

FISH analysis of the translocation breakpoints: (a) FISH analysis with the BAC RP11-730B22 (green) located in 7p22.1 and a centromeric probe of chromosome 16 (red), shows that this BAC is spanning the breakpoint on chromosome 7. (b) FISH analysis with BACs RP11-264M14 (green) showed that it spans the translocation breakpoint located on 16p11.2. It was hybridised with a chromosome 7 centromeric probe (red). (Chr.: chromosome, Der.: derivative).

Although we did not identify the actual sequence of the breakpoint on 7p22.1, we located it by BAC-FISH mapping between nucleotides 4933257 and 5107654.

According to Ensembl genome database (May 2006 version), there are 3 coding sequences corresponding to NP_976327.1, RBAK (RB-associated KRAB zinc finger) and RNF216L or Q6NUR6 (E3 UBIQUITIN LIGASE TRIAD3 EC6.3.2.) genes.

Seven but four BAC clones located on 16p11.2 gave two distinct hybridization signals on the normal 16p and the derivative 16 (see Table 1). The overlapping BAC, RP11-264M14, hybridized to both derivative 16 and derivative 7 chromosomes and to the normal chromosome 16, but not to the normal chromosome 7 (see Figure 3(b)). The clone RP11-264M14, on 16p11.2, was found to be devoid of known genes.

5. DISCUSSION

Genetic studies have yielded suggestive linkage and association to several different chromosomal regions, but up to now, the large number of association studies using a candidate gene approach has had limited success [7–10]. As an alternative approach, the characterisation of different types of chromosomal abnormalities could result in the identification of candidate genes for autism [11, 12]. Chromosomal abnormalities detected by cytogenetics or molecular cytogenetics are of major aid to locate relevant genes. About 3–5% of autistic patients have a chromosome abnormality visible with cytogenetic methods [13]. Almost all chromosomes have been involved including translocations and inversions resulting in disruption of genes at the breakpoints [14, 15].

Balanced chromosome rearrangements are observed at a significantly increased rate. Gillberg and Wahlström [16], in an epidemiological study done on 66 individuals with autism located in Sweden, found that less than 5% of the group had major chromosomal abnormalities. The same rate was found by Castermans et al. [17] when they karyotyped 525 individuals with idiopathic autism. This rate is much higher than would be expected from a general population (1/2000 for a reciprocal translocation and 1/10000 for an inversion) [18]. This suggests that certain chromosome aberrations like translocations, deletions, or inversions may involve genes acting as susceptible factors for autism.

In this article, we describe a 10-year-old child carrying a de novo balanced (7;16)(p22.1;p16.2) translocation associated with an autistic disorder, psychomotor delays, and no dysmorphic features.

This case represents both an unusual and useful opportunity to examine and compare the cytogenetic and the common physical features with the previously reported cases of autism and these specific regions. In Table 2, an overview is given of all patients with chromosomal anomalies involving the 7p22.1 and 16p11.2 regions that have been described in the literature. In the best of our knowledge, it is the first time the autism phenotype has been associated with a translocation in these specific chromosomal regions.

Table 2.

Autism related breakpoints on 7p22p and 16p11.2.

| Chromosome | Karyotype | Phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chr16 | 46, XX, dir dup(16)(p11.2p12.1) | autism, mild mental retardation | Finelli et al. [20] Engelen et al. [21] |

| Chr16 | 46, XY, dir dup(16)(p11.2p12) de novo | autistic behaviour, psychomotor retardation | Carrasco Juan et al. [22] |

| Chr16 | 46, XY, inv(2)(p11.2q13), 16qh- | autism | Vorsanova et al. [23] |

| Chr7 | del (7)(p22.2p22.2) | autism | Yu et al. [24] |

Chromosome 16p has been identified by a number of genome screens for autism and is likely to contain an autism-susceptibility variant. The 7p locus has been less consistently reported than the chromosome 16p one. Both regions remain an important area for future research [19].

Regarding the locus on 16p11.2, only duplications and one inversion have been reported [20–23]. Looking at the overall clinical phenotype of our patient and the literature described ones, the only shared features seem to be autistic behaviour. The observed phenotypic variety may be caused by the dissimilarity in the nature of the chromosomal abnormalities and by the size and the content of the interval.

Large-deletion alleles on chromosome 7p22 were found in kindreds with autism but not in healthy control subjects [24]. In these regions, genes are likely to contribute to autism in the individuals with the cytogenetic abnormality but appear to lack a significant effect at the population level. More than 100 genes have been mapped in the deleted interval (http://genome.ucsc.edu/), and so it is only possible to speculate about the potential role of specific genes in autism.

According to Ensembl genome databases, there are few genes listed in the breakpoint region on 7p22.1 : NP_976327.1, which is a hypothetical gene expressed in the cerebellum, RBAK gene may contribute to transcriptional activation and cell cycle arrest and RNF216L or Q6NUR6 gene which may be an E3 ubiquitin ligase. On the basis of their functions and expression patterns, these genes can be considered as candidate genes for autism.

Interestingly, the disruption of one of these genes by the translocation may cause a decreased dosage responsible for specific tissue and developmental effects leading to autistic traits. This is in agreement with the deletions on 7p22 reported on autistic patients by Yu et al. [24].

The characterisation of the translocation breakpoints will let as to narrow the interval and to identify candidate genes causative of the observed phenotype in our patient.

In conclusion, the case report presented here (1) places further emphasis on the importance of molecular cytogenetics in the study of de novo apparently balanced translocations with abnormal phenotype and (2) confirms the possibility that genes with an important contribution to the pathogenesis of autism are located in regions of the genome for which cytogenetic abnormalities have not been reported so far.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the patient and his family for their cooperation.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th edition. Washington, DC, USA: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fombonne E. The prevalence of autism. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(1):87–89. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hallmayer J, Glasson EJ, Bower C, et al. On the twin risk in autism. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2002;71(4):941–946. doi: 10.1086/342990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gillberg C. Chromosomal disorders and autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1998;28(5):415–425. doi: 10.1023/a:1026004505764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wassink TH, Piven J, Patil SR. Chromosomal abnormalities in a clinic sample of individuals with autistic disorder. Psychiatric Genetics. 2001;11(2):57–63. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200106000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Autism Genome Project Consortium Mapping autism risk loci using genetic linkage and chromosomal rearrangements. Nature Genetics. 2007;39(3):319–328. doi: 10.1038/ng1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klauck SM. Genetics of autism spectrum disorder. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2006;14(6):714–720. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bacchelli E, Maestrini E. Autism spectrum disorders: molecular genetic advances. American Journal of Medical Genetics C. 2006;142(1):13–23. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta AR, State MW. Recent advances in the genetics of autism. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61(4):429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freitag CM. The genetics of autistic disorders and its clinical relevance: a review of the literature. Molecular Psychiatry. 2007;12(1):2–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu J, Zwaigenbaum L, Szatmari P, Scherer SW. Molecular cytogenetics of autism. Current Genomics. 2004;5(4):347–364. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacquemont M-L, Sanlaville D, Redon R, et al. Array-based comparative genomic hybridisation identifies high frequency of cryptic chromosomal rearrangements in patients with syndromic autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2006;43(11):843–849. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.043166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vorstman JAS, Staal WG, van Daalen E, van Engeland H, Hochstenbach PFR, Franke L. Identification of novel autism candidate regions through analysis of reported cytogenetic abnormalities associated with autism. Molecular Psychiatry. 2006;11(1):18–28. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castermans D, Wilquet V, Parthoens E, et al. The neurobeachin gene is disrupted by a translocation in a patient with idiopathic autism. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2003;40(5):352–356. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.5.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sultana R, Yu C-E, Yu J, et al. Identification of novel gene on chromosome 7q11.2 interrupted by a translocation breakpoint in a pair of autistic twins. Genomics. 2002;80(2):129–134. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gillberg C, Wahlström J. Chromosome abnormalities in infantile autism and other childhood psychoses: a population study of 66 cases. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 1985;27(3):293–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1985.tb04539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castermans D, Wilquet V, Steyaert J, van de Ven W, Fryns J-P, Devriendt K. Chromosomal anomalies in individuals with autism: a strategy towards the identification of genes involved in autism. Autism. 2004;8(2):141–161. doi: 10.1177/1362361304042719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McFadden DE, Friedman JM. Chromosome abnormalities in human beings. Mutation Research. 1997;396(1-2):129–140. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(97)00179-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lamb JA, Parr JR, Bailey AJ, Monaco AP. Autism: in search of susceptibility genes. NeuroMolecular Medicine. 2002;2(1):11–28. doi: 10.1385/NMM:2:1:11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finelli P, Natacci F, Bonati MT, et al. FISH characterisation of an identical (16)(p11.2p12.2) tandem duplication in two unrelated patients with autistic behaviour. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2004;41(7):e90. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.016311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engelen JJM, de Die-Smulders CEM, Dirckx R, et al. Duplication of chromosome region (16)(p11.2 → p12.1) in a mother and daughter with mild mental retardation. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2002;109(2):149–153. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carrasco Juan JL, Cigudosa JC, Otero Gómez A, Acosta Almeida MT, García Miranda JL. De novo trisomy 16p. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1997;68(2):219–221. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19970120)68:2<219::aid-ajmg19>3.3.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vorsanova SG, Yurov IYu, Demidova IA, et al. Variability in the heterochromatin regions of the chromosomes and chromosomal anomalies in children with autism: identification of genetic markers of autistic spectrum disorders. Neuroscience and Behavioral Physiology. 2007;37(6):553–558. doi: 10.1007/s11055-007-0052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu C-E, Dawson G, Munson J, et al. Presence of large deletions in kindreds with autism. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2002;71(1):100–115. doi: 10.1086/341291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]