Abstract

We have used a structure energy-based computer program developed for protein design, Perla, to provide theoretical estimates of all specific side chain–side chain interaction energies occurring in α helices. The computed side chain–side chain interaction energies were used as substitutes for the corresponding values used by the helix/coil transition algorithm, AGADIR. Predictions of peptide helical contents were nearly as successful as those obtained with the originally calibrated set of parameters; a correlation to experimentally observed α-helical populations of 0.91 proved that our theoretical estimates are reasonably correct for amino acid pairs that are frequent in our database of peptides. Furthermore, we have determined experimentally the previously uncharacterized interaction energies for Lys–Ile, Thr–Ile, and Phe–Ile amino acid pairs at i,i + 4 positions. The experimental values compare favorably with the computed theoretical estimates. Importantly, the computed values for Thr–Ile and Phe–Ile interactions are better than the energies based on chemical similarity, whereas for Lys–Ile they are similar. Thus, computational techniques can be used to provide precise energies for amino acid pairwise interactions, a fact that supports the development of structure energy–based computational tools for structure predictions and sequence design.

Keywords: α Helix, helix/coil transition, peptide design, secondary structure

In recent years, enormous progress in the design of small proteins was made. Several computational approaches have been used to successfully design, in an automatic and rational fashion, protein cores (Dahiyat and Mayo 1996; Lazar et al. 1997; Desjarlais and Handel 1995; Lacroix 1999), protein surfaces (Dahiyat et al. 1997; Lacroix 1999) and a whole protein (Dahiyat and Mayo 1997). To design proteins efficiently, algorithms use a structural, atomic representation to model polypeptide sequences. Amino acid side chains are reconstructed on a defined structural template, and a sequence-structure–stability relationship is established to determine which sequences are advantageous according to a combination of molecular mechanics energy terms and statistical potentials for polypeptide solvation and entropy changes.

To test the nature of the energy function, molecular systems simpler than proteins could be used as, for instance, alanine-based α-helical peptides. The large amount of data available and the existence of computer programs able to predict the population of folded molecules with considerable accuracy (Lifson and Roig 1961; Muñoz and Serrano 1994a; Chakrabartty and Baldwin 1995; Andersen and Tong 1997; Lomize and Mosberg 1997; Misra and Wong 1997; Lacroix et al. 1998) are advantages supporting the use of helical peptides as models for the precise analysis of interaction energies determined from tridimensional models. An important similarity between computer programs developed for protein design and those used for helical content prediction is the pairwise expression of energy terms representing side chain interactions. Thus, one type of algorithm can be used as benchmark system for the development and refinement of the other.

Using our protein design computer program, Perla (Lacroix 1999), we have modeled all possible amino acid pairs placed in i,i + 3 and i,i + 4 positions at the center of an alanine-based α helix (Fig. 1 ▶). Theoretical estimates of the energies specific to the side chain interactions (ΔGSC) were obtained performing double-mutant cycles to follow a common experimental strategy (Fersht et al. 1992). These theoretical estimates were tested with AGADIR (Muñoz & Serrano 1994a; Lacroix et al. 1998), a fast and reliable algorithm for the prediction of α-helical contents, substituting the side chain interaction parameters by the calculated values. Finally, the interaction energies for three experimentally uncharacterized i,i + 4 amino acid pairs were determined experimentally and compared with the related theoretical estimates. Our results show that computational techniques can provide precise interaction energies for amino acid pairwise interactions.

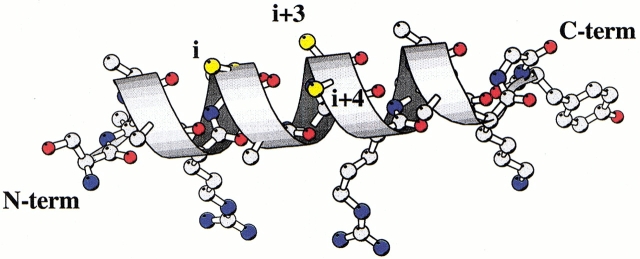

Fig. 1.

Ribbon representation of a model α helix. Some side chains are shown with atomic details. A pattern of i,i + 3 and i + 4 positions is shown in yellow.

Results

Analysis of the specific side chain interaction energies used by AGADIR

A number of tests were performed to determine whether a precise evaluation of i,i + 3 and i,i + 4 side chain interaction energies (ΔGSC) is essential to the success of the helix/coil transition method. We first tested AGADIR to confirm the necessity to include such interaction energies, analyzing the prediction of helical contents when all corresponding energy parameters are set to zero (both i,i + 3 and i,i + 4 interactions). Second, to determine the precision that the interaction energies should have to keep the correlation between predicted and experimental helical contents high enough, we have created new sets of parameters by adding a small energy perturbation, taken at random in a predetermined interval, to the side chain–side chain data sets of AGADIR, and recomputed the helical contents. Third, we checked the relevance of the assignment of interaction energies to specific pairs of side chains by rearranging randomly the i,i + 3 and i,i + 4 data sets.

Table 1 compares directly the side chain–side chain data sets of AGADIR to the perturbed data and summarizes the impact of the energy perturbations on the correlation between the prediction by AGADIR and the observed helical contents. The agreement between predicted and observed helical contents, for a set of 395 peptides (see Materials and Methods), significantly drops from rHel = 0.94 to rHel = 0.79, when all side chain–side chain interactions are set to zero. The modified sets of parameters obtained through the addition of a random noise have broader intervals of interaction energies. The larger the noise, the larger the interval and the lower the correlation to the initial data sets. In parallel, the agreement of the predictions by AGADIR with the experimental helical contents is decreasing (see the rHel correlation in Table 1). To keep a correlation between predictions and experiments of 0.9 (or above), the highest acceptable error is 0.3 kcal mole−1. The randomly reorganized interaction energies, which preserve the energy values in nonspecific patterns (no correlation to the correct data sets), produce poor agreement between predictions and experiments. Hence, the correct assignment of interactions energies to specific amino acid pairs is necessary to produce good estimations of peptide helical populations.

Table 1.

Agreement between predictions of AGADIR and experimentally determined helical contents, and comparison of the data sets representing the i,i+3 and i,i+4 specific side chain interaction energies

| Sets of parameters | 〈x〉i+3 | σi+3 | ri+3 | 〈x〉i+4 | σi+4 | ri+4 | rHel |

| AGADIR | −0.04 | 0.15 | 1.00/1.00 | −0.07 | 0.25 | 1.00/1.00 | 0.94 |

| Zeros | 0.0 | — | — | 0.0 | — | — | 0.79 |

| Noise addeda | |||||||

| ΔGSC ± 0.1 | −0.04 | 0.16 | 0.89/0.93 | −0.07 | 0.26 | 0.95/0.97 | 0.93 |

| ΔGSC ± 0.2 | −0.04 | 0.19 | 0.69/0.78 | −0.06 | 0.28 | 0.84/0.92 | 0.93 |

| ΔGSC ± 0.3 | −0.03 | 0.21 | 0.46/0.62 | −0.07 | 0.31 | 0.75/0.83 | 0.90 |

| ΔGSC ± 0.4 | −0.04 | 0.27 | 0.55/0.54 | −0.09 | 0.33 | 0.31/0.71 | 0.85 |

| ΔGSC ± 0.5 | −0.06 | 0.32 | 0.35/0.44 | −0.10 | 0.39 | 0.60/0.65 | 0.83 |

| ΔGSC ± 1.0 | −0.05 | 0.60 | 0.12/0.28 | −0.10 | 0.60 | 0.34/0.35 | 0.76 |

| Randomized dataa | |||||||

| Shuffle a | −0.04 | 0.15 | −0.19/−0.02 | −0.07 | 0.25 | 0.10/−0.05 | 0.84 |

| Shuffle b | −0.04 | 0.15 | −0.15/0.08 | −0.07 | 0.25 | 0.17/−0.05 | 0.83 |

| Shuffle c | −0.04 | 0.15 | −0.08/0.00 | −0.07 | 0.25 | 0.06/0.07 | 0.82 |

| Shuffle d | −0.04 | 0.15 | −0.16/0.00 | −0.07 | 0.25 | −0.03/−0.01 | 0.79 |

| Shuffle e | −0.04 | 0.15 | 0.11/0.04 | −0.07 | 0.25 | 0.02/0.07 | 0.79 |

a See text for details about the various data sets.

(〈x〉i+3) Average interaction energy for the i,i+3 side chain interactions; (σi+3) standard deviation for the i,i+3 side chain interactions; (ri+3) weighted correlation of the i,i+3 data set to that of AGADIR/regular correlation; (〈x〉i+4) average interaction energy for the i,i+4 side chain interactions; (σi+4) standard deviation for the i,i+4 side chain interactions; (ri+4) weighted correlation of the i,i+4 data set to that of AGADIR/regular correlation; (rHel) correlation between predicted and experimentally observed helical contents for our peptide database.

Computational estimation of specific side chain interaction energies

We have used Perla (see Materials and Methods) to determine theoretical estimates for all specific side chain interaction energies occurring in α helices. Two alanine-based structural templates of 16 residues were used to represent the α-helical folded state (Hel, φ≈−60° and ψ≈−40°) and an extended unfolded state (RC, φ≈−120° and ψ≈140°). Residues 7 and 10 or 11, were mutated to all 20 amino acids, thus modeling 800 sequences (each sequence with all possible combinations of the corresponding side chain rotamers) that contained either an i,i + 3 or i,i + 4-amino-acid pair. Double-mutant cycles were performed with the energies determined by Perla, EPerla, to extract the side chain interaction energies of amino acid pairs XY:

|

where Hel is the helical conformation and RC the extended conformation. Different calculations were performed with Perla, verifying how the data produced by the double-mutant cycle corresponded to the parameters used by AGADIR. Simultaneously, the calculated side chain–side chain energies were introduced into AGADIR and used to predict the experimental content of our peptide database.

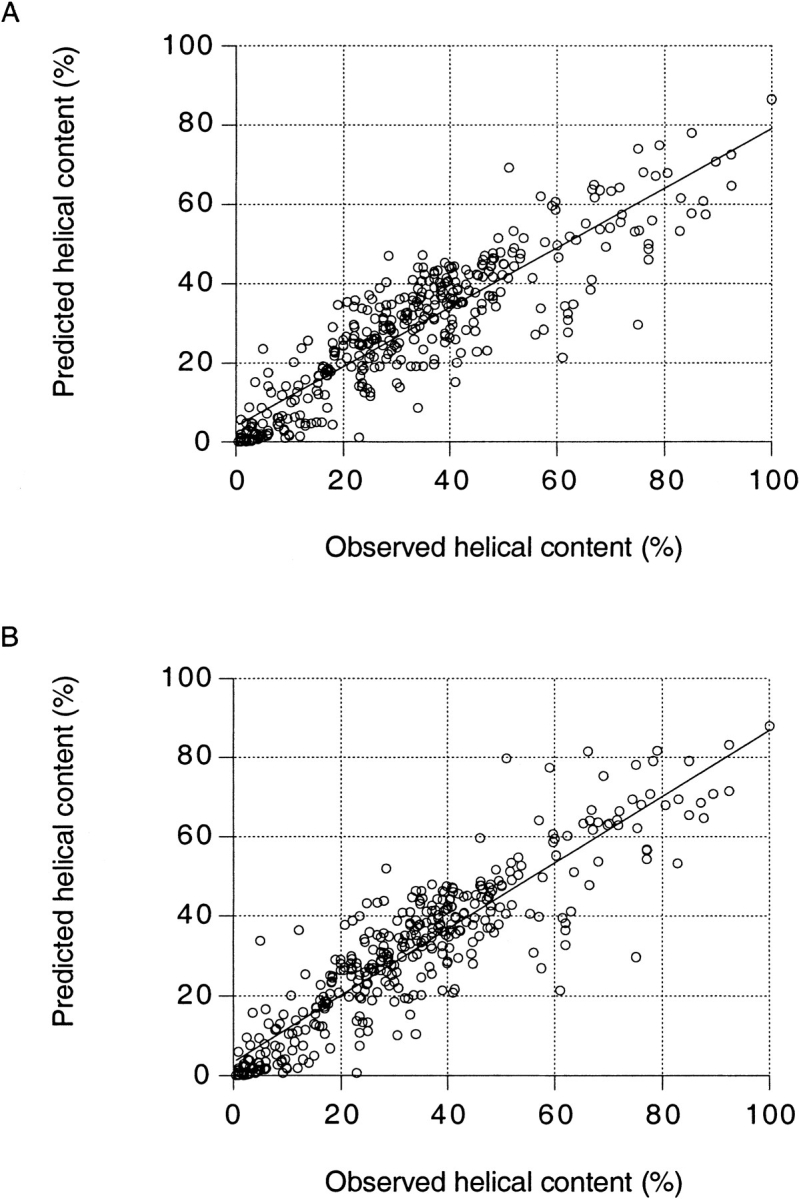

Table 2 presents the comparison of computed specific side chain i,i + 3 and i,i + 4 interaction energies with the data sets used by AGADIR, plus the correlation between experimental helical contents and predicted values using AGADIR and the computed data sets. The computed energy values are more broadly distributed than the parameters of AGADIR, as shown by the larger standard deviations, but have a mean value comparable to that of the AGADIR data sets. Importantly, although the calculated data sets are only partially correlated to the calibrated values used by AGADIR (r between 0.40 and 0.70), they can be used with AGADIR to obtain reasonably correct predictions of helical contents (rHel at least 0.90 for four of the new data sets; Fig. 2 ▶). In fact, the new interaction energies are comparable with the data sets we have generated previously adding a random noise in the [−0.3, +0.3] or [−0.4, +0.4] kcal mole−1 ranges, and they perform better than the shuffled data sets. Also, we have observed that the interaction energies calculated by Perla (data set that provides the highest rHel correlation; Table 2), Creamer and Rose (Creamer and Rose 1995) and those used in AGADIR enable similarly good predictions of helical contents for the subset of interactions between hydrophobic residues (rHel ∼ 0.94–0.95; data not shown). These results demonstrate that a double-mutant cycle performed with energies computed by Perla can produce reasonable interaction energies for i,i + 3 and i,i + 4 side chain interactions in α helices.

Table 2.

Agreement between predictions of AGADIR and experimentally determined helical contents, and comparison of the AGADIR and Perla data sets representing the i,i+3 and i,i+4 specific side chain interaction energies

| Sets of parameters | 〈x〉i+3 | σi+3 | ri+3 | 〈x〉i+4 | σi+4 | ri+4 | rHel |

| AGADIR | −0.04 | 0.15 | 1.0/1.0 | −0.07 | 0.25 | 1.0/1.0 | 0.94 |

| Zeros | 0.0 | — | — | 0.0 | — | — | 0.79 |

| Subrotamers: 2 × 5° | |||||||

| 150 K | −0.11 | 0.25 | 0.41/0.57 | −0.09 | 0.35 | 0.21/0.60 | 0.87 |

| 303 K | −0.08 | 0.24 | 0.60/0.34 | −0.05 | 0.34 | 0.49/0.23 | 0.90 |

| 350 K | −0.08 | 0.26 | 0.61/0.32 | −0.06 | 0.35 | 0.53/0.25 | 0.89 |

| 450 K | −0.07 | 0.32 | 0.60/0.25 | −0.04 | 0.40 | 0.40/0.20 | 0.86 |

| Subrotamers: 3 × 5° | |||||||

| 303 K | −0.08 | 0.23 | 0.62/0.32 | −0.11 | 0.33 | 0.66/0.33 | 0.87 |

| 350 K | −0.07 | 0.25 | 0.62/0.30 | −0.10 | 0.35 | 0.67/0.32 | 0.88 |

| 400 K | −0.07 | 0.28 | 0.61/0.26 | −0.08 | 0.36 | 0.60/0.28 | 0.90 |

| 450 K | −0.07 | 0.31 | 0.62/0.25 | −0.06 | 0.38 | 0.54/0.24 | 0.91 |

| 500 K | −0.06 | 0.34 | 0.61/0.23 | −0.06 | 0.41 | 0.55/0.24 | 0.90 |

See text for a description of the data sets obtained from calculations with Perla.

(〈x〉i+3) Average interaction energy for the i,i+3 side chain interactions; (σi+3) standard deviation for the i,i+3 side chain interactions; (ri+3) weighted correlation of the i,i+3 data set to that of AGADIR/regular correlation; (〈x〉i+4) average interaction energy for the i,i+4 side chain interactions; (σi+4) standard deviation for the i,i+4 side chain interactions; (ri+4) weighted correlation of the i,i+4 data set to that of AGADIR/regular correlation; (rHel) correlation between predicted and experimentally observed helical contents for our peptide database.

Fig. 2.

Prediction (by AGADIR) of the helical content for 395 peptides studied at pH between 6 and 8 and low ionic strength (part of the AGADIR database). The plot shows the prediction obtained with the parameters computed through the double-mutant cycle with the data calculated by Perla, with subrotamers and sampling temperature of 2 × 5° (A) and 303 K and 3 × 5° (B) and 450 K, respectively. Lines represent data fittings to linear equations.

A complete test of the theoretical estimates could not be achieved with the series of peptides used as a test database, however, because the majority (∼90%) of side chain–side chain interactions in the peptide sequences is represented by only one fourth of all possible amino acid pairs. Thus, most of the interaction energies in the i,i + 3 and i,i + 4 parameters sets do not contribute to the quality of the prediction of helical contents, and only about one fourth of the theoretical estimates can be considered correct (for computed parameters that give rHel at least 0.90). The data sets computed through double-mutant cycles with energy values determined by Perla are in fact only partially correlated to the parameters used by AGADIR (Table 2). An explanation is that the larger part of the computed data corresponding to interactions for which few or no cases are found in the peptide database, is quite divergent from the tabulated data of AGADIR. Larger energy differences for the infrequent amino acid interactions are indeed evidenced by the fact that the correlation established considering the importance of each amino acid pair in the peptide series (see Materials and Methods) is, in general, higher than the regular correlation.

Experimental test

The utility of the computational method (Perla) would be better demonstrated checking the accuracy of the theoretical estimates for several infrequent interactions, asking whether they are closer to the true values than the values of AGADIR. We chose to analyze experimentally the contribution to α-helix stability of the side chain–side chain interactions between Phe, Lys, or Thr and Ile placed one helical turn apart (in position i + 4; for the peptide series, see Materials and Methods). These specific interactions were not yet characterized experimentally and are not abounding in the peptide series used to test the prediction of helical contents: Only 6, 3, and 3 peptide sequences contain one or more KI, FI, or TI i,i+4 interactions, respectively, and there are in total 9, 4, and 3 cases of these interactions.

NMR analyses were performed for the series of peptides that corresponds to the double-mutant cycle of the TI interaction (peptides αAA, αAI, αTA and αTI). These experiments were conducted to demonstrate that the α-helical conformation ran across the peptide sequence from Ala2 to Lys16, a condition required to interpret the results in terms of helical side chain–side chain i,i + 4 interactions. Due to the high content in Ala residues, not all NMR peaks could be assigned unambiguously. Nevertheless, we could evaluate most conformational shifts (difference between observed chemical shifts and reference values typical of a random coil conformation) for 1Hα resonances. Negative conformational shifts typical of α helices were observed for residues 2–16 (data not shown).

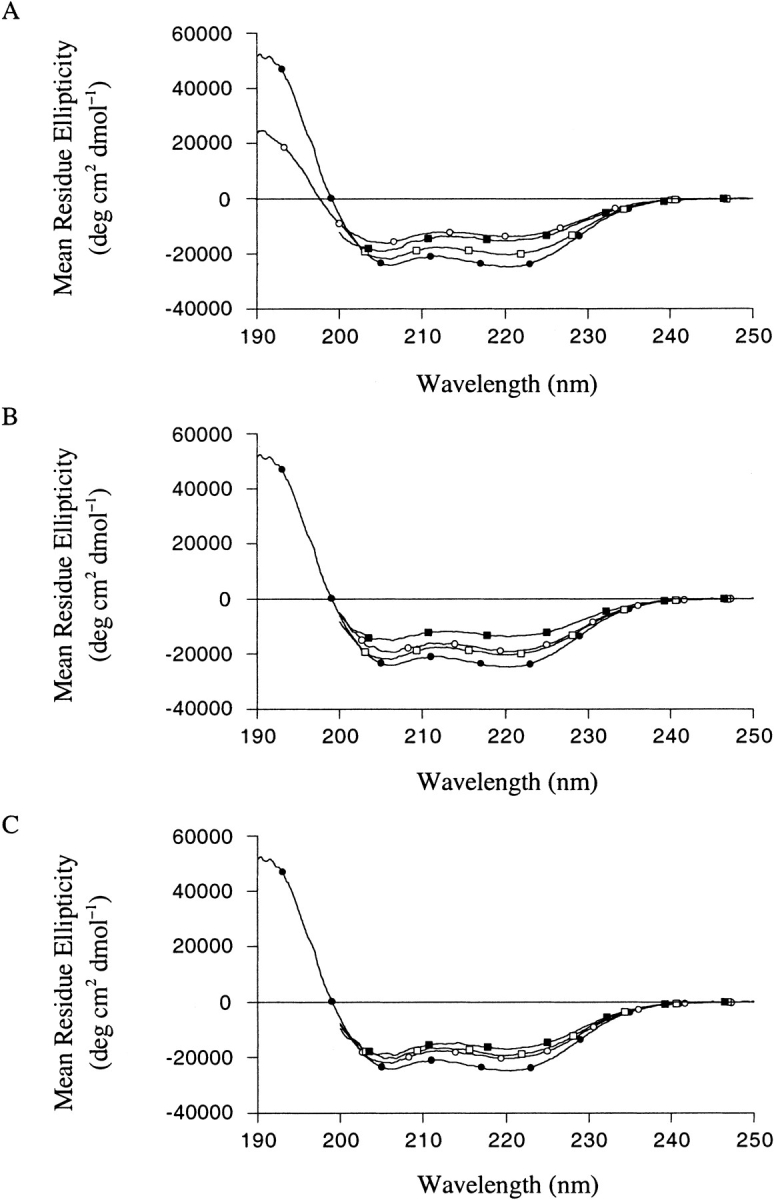

The helical conformation of the peptides was observed using CD spectroscopy. All far-UV CD spectra displayed curves typical of α helices with minima at 222 and 208 nm accompanied by a maximum around 190 nm (Fig 3 ▶). Helical contents were estimated from the signal at 222 nm obtained from three experiments, following the equation of Chen and co-workers (Chen et al. 1974). We estimate that the error made on the determination of the concentration leads to a maximum error in the helical content of approximately ±5% (the analysis of the R1 ratio (Bruch et al. 1991) indicates that the helical estimates are in fact more accurate). Table 3 summarizes the results of the CD measurements, and compares them with the predictions of AGADIR. After modifying the H-bonding contribution and the intrinsic propensities of Ile, Phe, Lys, and Thr (to match experimental and predicted helical contents of the αAI, αFA, αKA and αTA peptides; see Materials and Methods), the prediction for peptide αFI deviates significantly from the experimental data and that for peptide αTI is at the limit corresponding to experimental error. Thus, the specific side chain interaction energy used by AGADIR for the FI amino acid pair is not correct, while that used for the TI pair is quite inaccurate. Besides, if the interaction energies calculated with Perla are used instead of the AGADIR values, improved predictions are obtained for peptides αFI and αTI (Table 3), demonstrating that the theoretical estimates are good predictors for the interaction energies.

Fig. 3.

Far-UV CD spectra of the α-helical peptides, at pH 5 and 278 K. (Closed and open boxes) Peptides αAA and αAI, respectively. (A) Peptides αTA and αTI, (open and closed circles, respectively). (B) Peptides αFA and αFI, (open and closed circles, respectively). (C) Peptides αKA and αKI, (open and closed circles, respectively).

Table 3.

Helical content of the series of peptides analyzed by CD, at pH 5 and 278 K, and AGADIR predictions

| Peptide name | Observed (%) | AGADIRa | AGADIRb | AGADIRbc | AGADIRbcd | AGADIRbce |

| αAA | 65 | −4 | 0 | 0 | ||

| αAI | 59 | −7 | −2 | 0 | ||

| αFA | 58 | −10 | −5 | 0 | ||

| αKA | 57 | −4 | +1 | 0 | ||

| αTA | 47 | −8 | −2 | 0 | ||

| αFI | 49 | +5 | +9 | +15 | +7 | +8 |

| αKI | 51 | −5 | 0 | +2 | +5 | +5 |

| αTI | 45 | −15 | −9 | −5 | +2 | +2 |

a–e Differences (in percent points) between computed and observed helical contents.

a Standard version of the computer program.

b The contribution of the H-bond to helix stability was increased from −0.895 and −0.909 kcal mole−1

c The intrinsic propensities to adopt a helical conformation of Ile, Phe, Lys, and Thr were modified (from 1.08 to 1.0, 1.23 to 1.03, from 0.83 to 0.86, and from 1.51 to 1.45 kcal mole−1, respectively) to obtain an optimal prediction for the reference and single mutant peptides, so that the error of the prediction for the double mutant peptides is mainly due to the corresponding specific side chain interaction energies.

d,e Calculation using the best computed side chain interactions, using either 2 or 3 steps of 5° rotations to optimize the rotamer interaction energies (sampling temperatures were 303 K and 450 K, respectively).

The theoretical estimates for FI, KI, and TI interactions, derived from calculations with Perla, are compared in Table 4 with the specific side chain interaction energy values used in AGADIR and with interaction energies obtained fitting the prediction by AGADIR to the experimental helical contents of the corresponding three peptides. For the Phe–Ile interaction, the experimental net energy contribution is close to zero. The corresponding theoretical estimates (∼−0.27 kcal mole−1) are slightly off the error range defined tolerating a ±5% error range for the helical content predicted by AGADIR (still they are better than the −0.60 kcal mole−1 energy value normally used in AGADIR). For the Lys–Ile amino acid pair (−0.10 kcal mole−1), both the energy value used in AGADIR (−0.15 kcal mole−1) and the theoretical estimates (∼−0.27 kcal mole−1) lie within the ±5% error range (the value of AGADIR being slightly more accurate) and for the third amino acid pair, TI (−0.26 kcal mole−1), calculations with Perla produced interaction energies (∼−0.34 kcal mole−1) more accurate than the value of AGADIR (0.10 kcal mole–1).

Table 4.

Specific side chain interaction energies determined from experiments and calculations with Perla (double-mutant cycles), for FI, KI, and TI i,i+4 interactions

| Sets of parameters | FI | KI | TI |

| AGADIRa | −0.60 | −0.15 | −0.10 |

| Calibratedb | −0.0 | −0.10 | −0.26 |

| [Low, high]c | [+0.17, −0.17] | [+0.07, −0.28] | [−0.10, −0.44] |

| 2 × 5° 303 Kd | −0.24 | −0.27 | −0.35 |

| 3 × 5° 450 Ke | −0.29 | −0.26 | −0.33 |

a Standard version of the computer program.

b Experimentally determined values based on the eight peptides studied (see Materials and Methods).

c Lower and higher limits of the interaction energies, which would lead to under- and overestimation of the helical content by ∼5%.

d,e Interaction energies computed from calculations performed with Perla, using 2 and 3 steps of 5° rotations to optimize the rotamer interaction energies (the sampling temperature was set as indicated), respectively.Interaction energies in kcal mole−1.

Discussion

Amino acid specific side chain–side chain interaction energies were derived from sequence modeling calculations performed with Perla, through a double-mutant cycle, using as the structural template an element of secondary structure considerably well understood: the α helix. Our helix/coil transition computer program that predicts helical contents of peptides, AGADIR, was used to test the computed energy values.

Contribution of side chain interaction energies to helix/coil transition

Helix/coil transition methods include several terms that contribute significantly to helical content. In fact, AGADIR defines ΔGHel (the free energy change between helical and random coil states for a particular peptide segment), considering α-helix intrinsic propensities, capping effects, main chain hydrogen bonding, electrostatics, the interaction of charged groups with the helix macro dipole and i,i + 3 as well as i,i + 4 specific side chain–side chain interaction energies (Lacroix et al. 1998; Muñoz and Serrano 1994a). Thus, side chain interactions only add partially to the balance between coil and helix. Nonetheless, we have found them to be sufficiently important, even though a database containing polyalanine-based peptides was used for the test. Good predictions further require that the interaction energies be specific and precisely determined. Side chain interaction energies should not be more than ∼0.3 kcal mole−1 apart from the parameter values set in AGADIR, if a correlation between predicted and observed helical content of at least 0.9 is to be kept. Also, we have shown that the distribution of energy values cannot be modified. This means that the energy term specifically attributed to side chain interactions truly performs its function, that is, the favorable impact on predictions is not due to the addition of a proper though unspecific amount of energy to the free energy of helical segments.

Overall quality of the data produced with Perla via the double-mutant cycle

With the double-mutant cycle, the contribution to helix stability specific to the side chain interactions of pairs of amino acids disposed in i,i + 3 or i,i + 4 patterns was evaluated from estimates of folding free energies determined using Perla. Predictions of helical contents by AGADIR, using the computed interaction energies, were in general superior to the predictions obtained with randomly redistributed parameters. Together with positive correlations to the data sets of AGADIR, this observation indicates that the computed interaction energies preserve the necessary specific assignment of interaction energies to particular pairs of amino acids. In other words, favorable and destabilizing interactions are computed where they are due. Moreover, the extent of precision of the best computed data is likely to be similar to that of the perturbed data set that contained an error within ±0.3 kcal mole−1.

Calibration of Perla

Using the quality of the prediction obtained with AGADIR as a selection criterion, we have determined that the most advantageous energy parameters (to represent accurately most of the i,i + 3 and i,i + 4 side chain interactions) were obtained from data sets constructed from two alternative calculations by Perla. Both calculations were performed scaling the force field energies of Perla by a factor of 0.5, except for the solvation energy term. They differ, however, in the manner used to optimize the rotamer interactions with the peptide template and with neighboring side chain rotamers. In one case, the conformational space available to the rotamers was determined by rotations within 10° of the configurations specified by the rotamer library, and optimal results were obtained with the standard sampling temperature (303 K). In the other case, larger rotations were permitted (up to 15°), and optimal results were obtained only if the sampling temperature was raised (to 450 K).

It is not straightforward to explain how the calculations performed with different optimization protocols apparently converged. Thanks to the larger rotations of the 3 × 5° protocol, side chains are more easily accommodated, the interaction energies are more favorable, and possibly, too stabilizing. Indeed, if ideal rotameric states were not possible, the α helix would most probably not fold. With the sampling temperature increase, the relative importance of unlikely favorable pairs of subrotamers (combinations of 15° rotations) is lessened, the interaction energies being leveled up toward those measured with fewer subrotamers. The dependence on sampling temperature of the average of the i,i + 4 interaction energies, for the calculations with three rotation steps (in either direction; Table 2), supports the possibility of a too efficient optimization being opposed by the generation of more uniform conformational samplings.

An interesting point is the fact that, to obtain a good estimation of the side chain–side chain interaction energies, we need to soften the force field energies of Perla. Several factors could contribute to the imprecision and overestimation of the interaction energies: systematic errors of the scoring function, conformational rearrangements of the peptide structure, and insufficient consideration of energy changes occurring in the protein unfolded state. Because peptides adopt multiple conformations, the structural representation issue is more complicated, and could be critical. For instance, the use of a unique regular α helix as a folded state and a unique regular extended peptide as the unfolded state seems to be, a priori, a poor simplification. The formation of contacts in the unfolded state ensemble and the attenuation of interaction energies in expanded configurations connected to the folded state ensemble both promote the reduction of the specific side chain interaction energies that favor (or not) the formation of an α helix. Hence, more adequate effective interaction energies would be computed if intermediate configurations (i.e., locally compact structures and irregular helical conformations) were considered. However, the overall success of AGADIR for prediction of helical contents, and the possibility to provide reasonable interaction energies assuming a two-state system as a basis for the structural templates used by Perla, demonstrate that there are viable alternatives to the precise description of the conformational space (as long as properly calibrated parameters are used).

Calculation of specific side chain interaction energies for subsets of hydrophobic or polar/charged amino acids

Creamer and Rose (1995) proposed a method to estimate specific side chain interaction energies in α helices, for hydrophobic residues only, using defined rotation steps to sample side chain conformations. As mentioned above, the hydrophobic subsets of side chain interaction energies obtained with Perla and those estimated by Creamer and Rose perform equally well when used as predictive parameters in AGADIR. For the computation of interaction energies between polar/charged amino acids, difficulties could be expected because of the more complex nature of the effective energy terms. The right balance of electrostatics, hydrogen bonding, entropy, and solvation has to be established, whereas for hydrophobic amino acids mostly van der Waals is important. In our calculations, we were able to tune the energy function of Perla to obtain good estimations of polar/charged interaction energies, which are as significant as interaction energies between hydrophobic residues. For instance, at positions i,i + 3, computed EK and KE interactions are worth ∼−0.3 kcal mole−1, in accordance with energy values used in AGADIR and those calibrated by Baldwin and co-workers (Scholtz et al. 1993). Our estimations for the EK (∼−0.2 kcal mole−1) and KE (∼−0.3 kcal mole−1) i,i + 4 interactions are not found to be as stabilizing as measured previously (about −0.5 kcal mole−1; Scholtz et al. 1993), though.

An advantage of our method is the use of rotamers instead of the more exhaustive conformational sampling chosen by Creamer and Rose (1995). This renders calculations faster, which is important to handle the broader number of conformations available to large side chains as Glu, Arg, and Lys. Yet, some chemical groups cannot be well represented by any small discrete set of conformations. Our calculations thus failed to attribute sufficient interaction energy to some hydrogen bonds, as optimal geometrical conditions were not met due to the discretized representation of carboxylic groups (data not shown). This explains the weak i,i + 4 EK and KE interactions. A similar problem is found with the hydrogen bonded QD (Huyghues-Despointes et al. 1995) and QN (Stapley and Doig 1997) i,i + 4 pairs. Our calculations predict no significant interaction at all, whereas these should be strongly stabilizing (−1.0 and −0.54 kcal mole−1 for QD and QN, respectively).

Prediction of uncharacterized side chain–side chain interaction energies

The values used by AGADIR are based on experimental determinations of helical contents and calibrations of specific amino acid interactions within the framework of statistical mechanics. Yet, not all of the possible 800 amino acid pairs (considering both i,i + 3 as well as i,i + 4 interactions) were analyzed experimentally. Uncharacterized energies were estimated, taking into account the known contribution of amino acid pairs that have similar physicochemical properties (e.g., the i,i + 4 interaction energy for Phe–Val and Trp–Val amino acid pairs was set to −0.30 kcal mole−1 by analogy to the experimentally measured specific interaction energy for the Tyr–Val pair). If there were no experimental data available for chemically similar amino pairs, the interaction energy was simply set to zero. Therefore, values established for infrequent amino acid pairs are quite uncertain. This is clearly demonstrated by the fact that AGADIR can perform very well when using side chain interaction energy parameters correlated only partially to its current sets of values.

Perla has led to the determination of reasonably correct energy values for the previously uncharacterized Lys–Ile, Phe–Ile and Thr–Ile i,i + 4 interaction energies, as was illustrated by the experimental characterization of related peptides and the subsequent determination of the actual interaction energies. Very importantly these values are derived from two different series of calculations, selected independently because of the overall good results obtained when used in AGADIR to predict the helical content of our peptide database. We should emphasize the fact that these pairs could only have a trivial influence on the AGADIR performance test, as there were very few sequences containing these particular amino acid pairs in our series of nearly 400 peptides (KI, FI and TI i,i + 4 interactions represent 0.2%, 0.1%, and 0.1% of the total number of interactions existing in our peptide series, respectively). Furthermore, it is exceptionally valuable that for two of the three amino acid pairs (FI and TI), the computed values are better than those used by AGADIR.

Conclusions and perspectives

A computer program that models amino acid sequences with structural details should use a sensible energy function. The correspondence between the energy parameters and experimental values provides a validation of the method of the computer program and enables a more intuitive comprehension of the computing process. We have shown that the energy function of Perla can be used to obtain a correct expression of side chain interactions in α helices, although refinements are required to better determine hydrogen bonding. Furthermore, our results suggest that secondary structure prediction algorithms could be constructed as Perla, using thus an explicit structural description instead of the more empirical, conformation-independent energy terms. Alternatively, computer simulations could be used to determine ab initio the optimal energy values for parameter sets not characterized experimentally, as our estimations of the KI, FI, and TI interaction energies demonstrate. Similarly, Perla could be used to obtain interaction energies for β hairpins and β sheets thus allowing, in the future, the prediction of their formation in a quantitative manner, as is currently done for α helices with good accuracy.

Materials and methods

Computational estimation of specific side chain interaction energies with Perla

A detailed description of the algorithm is available elsewhere (http://ProteinDesign.EMBL-Heidelberg.DE). Here, we just summarize those aspects relevant to this project. Perla builds selected amino acids in a polypeptide structural template. For this process, the program uses a custom-made side chain rotamer library constructed from the analysis of the protein database wherein all-atom configurations are given. The occupancy distribution of every side chain rotamer, for each sequence considered, is determined by use of the mean-field approximation (Koehl and Delarue 1994) with a temperature simulated annealing. The ECEPP/2 molecular mechanics energy force-field (Momani et al. 1975; Nemethy et al. 1983) is used to calculate the interaction energies. Van der Waals, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic (with a distance-dependent dielectric constant of 8.0) interaction energies are optimized, taking into account the side chain flexibility by sampling subrotamer configurations (obtained through rotations). An approximation of solvation energy changes (Street and Mayo 1998) is used during the side chain conformational sampling. After sampling, a single conformation defined by the set of the most likely side chain rotamers is used to re-evaluate the solvation energy from solvent accessible surface areas (ASA) with the solvation parameters of Eisenberg and McLachlan (1986). ASA calculations are realized with the NSC routine (Eisenhaber et al. 1995). Entropy is considered separately for the main chain and side chains. For the polypeptide backbone, tabulated entropy costs representing losses of conformational freedom are used (Muñoz and Serrano 1994b). For side chains, conformational entropy is determined from the probability distribution of all possible rotamers, which is produced from the mean-field approximation sampling method. In this work, the molecular mechanics force-field energies and entropy changes have been scaled by a factor 0.5.

Prediction of α-helical content with AGADIR

Perla computes energy terms assuming a neutral pH and low ionic strength, whereas AGADIR (Lacroix et al. 1998) is sensitive to pH values and salt concentrations. AGADIR, in fact, separates the electrostatic part (ΔGele) from the side chain interaction energy term, to include the dependence on pH and ionic strength. We have used a modified version of the helix/coil transition algorithm that considers only ΔGSC as if ΔGSC and ΔGele were combined into a unique energy term. We constructed two new data sets for the side chain–side chain interactions, adding the values corresponding to ΔGSC and ΔGele for all i,i +3 and i,i +4 interactions, setting the pH to 7, the ionic strength to 1 mM and the temperature to 298 K. These new side chain interaction energies can be used by the modified version of AGADIR, to predict the helical content of peptides characterized at pH and ionic strengths close to 7 and 1 mM, respectively. The effect of temperature on the helical content can still be modeled with the modified version of AGADIR, although with less precision, as the electrostatic energy is not determined any longer according to the temperature-dependent dielectric constant. All references to AGADIR, or to the side chain interaction data sets, correspond to the modified version of the algorithm and to the combined energies (if not explained otherwise). The database of helical peptides used during the development of AGADIR was filtered to extract 395 peptide sequences characterized at neutral pH and low ionic strength (pH between 6 and 8 and ionic strength below 5 mM). This reduced database of peptides was used to test the quality of the predictions of AGADIR, and its dependence on the actual sets of parameters used to describe the i,i + 3 and i,i + 4 interaction energies. For the test related to the hydrophobic interactions only, we have used the standard version of AGADIR (because these interactions are pH independent) and a database of 324 peptides (not filtered for pH or ionic strength), each peptide containing at least one hydrophobic i,i + 3 or i,i + 4 side chain interaction. Conventional statistics was used to calculate the mean values and standard deviations of the sets of parameters. Estimations of the correlation between the i,i + 3 or i,i + 4 data sets (ΔGSC) of AGADIR and any computed data set were obtained by use of regular statistics except for the weighted correlation described in Equation (1), where XY denotes one of the possible 400 amino acid pairs. The number of cases (NXY) and total number of side chain interactions (Ntotal) were determined by counting of the number of occurrences in the series of 395 peptides.

|

1 |

Calibration of the energy function of Perla

Interaction energies derived from calculations based on the standard ECEPP/2 energy force-field would give a correlation between predicted and observed helical contents in the 0.5–0.8 range. Better results are obtained scaling down the energy terms of the scoring function except for solvation. We used weights of 0.5 for the van der Waals, electrostatic, and hydrogen bonding energy terms. We have also divided by 2.0 the entropy losses for reducing the conformational space of the side chains. Note that the double-mutant cycle expressly removes the contribution of the side chain conformation-independent terms, such as the backbone entropy loss and the reference state parameters used by Perla for solvation and side chain entropy. Perla optimizes the interaction energies taking into account the side chain flexibility, which affects significantly the specific interaction energies extracted in double-mutant cycles. Hence, we have varied systematically the sampling temperature and the number of subrotamers. Subrotamers are constructed by Perla rotating the first two dihedral angles of the side chains taken from the rotamer library, using defined numbers of steps and step sizes (e.g., two steps of ±5°). The sampling temperature (normally around 300 K) is used to set up the mean field-based distribution of side chain rotamers and the subrotamer distributions that affect individual interaction energies. It controls the manner in which the interaction energies are weighted plus the side chain conformational entropy changes.

Design of the peptides

We have used the following sequence (as in Fig. 1 ▶) as a host to study the FI, KI, and TI side chain interactions: Ac-SAAAR AXiAAAYi+4RAAAKGY-Am.

The choice of amino acids ought to promote the formation of a highly populated α helix. Both peptide termini were protected with uncharged groups to remove the electrostatic repulsion between the charged ends and the helix macrodipole (partial charges located at the ends of the helix): the N-terminal group was acetylated (Ac-) and the C-terminal amidated (-Am). The first residue, Ser, is able to form a hydrogen bond with the free amide group of the fourth residue, thereby capping the helix (Doig et al. 1994). A Lys and two Arg residues were added to prevent peptide aggregation. The final Tyr serves as a spectroscopic probe to determine peptide concentrations; a Gly that acts as a flexible linker separates the Tyr from the helix to diminish the contribution of the aromatic ring to the far-UV circular dichroism (Chakrabartty et al. 1993). In total, eight peptides were synthesized: αAA, Ac-SAAARAAAAAARA AAKGY-Am; αAI, Ac-SAAARAAAAAIRAAAKGY-Am; αFA, Ac-SAAARAFAAAARAAAKGY-Am; αKA Ac-SAAARAKAA AARAAAKGY-Am; αTA, Ac-SAAARATAAAARAAAKGY-Am; αFI, Ac-SAAARAFAAAIRAAAKGY-Am; αKI, Ac-SAAA RAKAAAIRAAAKGY-Am; αTI Ac-SAAARATAAAIRAAAK GY-Am.

Peptide synthesis

Peptides were synthesized on polyoxyethylene–polystyrene graft resin. Chain assembly was performed by use of Fmoc chemistry (Carpino and Han 1972) and activation of amino acid building blocks by PyBOP (Coste et al. 1990). Peptides were purified by reverse phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC). Homogeneity (>98%) was determined by HPLC, and the molecular weight was checked by matrix-assisted laser desorption mass spectrometry (MALDI).

Determination of peptide concentrations

Peptide concentrations were determined, by use of the method of Gill and von Hippel (1989), from the absorbance (A280) of tyrosine residues.

NMR spectroscopy

NMR experiments were performed on either a Bruker DRX-500 or Bruker DRX-600 spectrometer at 280 K. Samples were about 1 mM peptide in 0.5 mL of H2O/D2O (9:1 vol/vol). pH was 5.0 (adjusted with HCl or NaOH). As an internal reference, 0.1 mM sodium 3-trimethylsilyl (2,2,3,3–2H4) propionate (TSP) was used at 0 ppm. Conventional pulse sequences and phase cycling were used for the two-dimensional total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY) and nuclear Overhauser enhancement spectroscopy (NOESY) experiments. Data were processed with the program X-WINNMR from Bruker.

Far-UV circular dichroism

CD spectra were recorded on a Jasco-710 instrument calibrated by use of D-10-camphorsulfonic acid. Measurements were made every 0.1 nm, with a response time of 1 s and a bandwidth of 1 nm, at a scan speed of 50 nm/min. Spectra shown in the text are the average of 30 scans, which were corrected for the baseline signal. Peptide concentrations were 10 μM and spectra were recorded in 5 mM sodium acetate (pH 5) at 278 K, in a cuvette with a 5-mm path.

Determination of the helical percentage from CD spectra

Helical populations of the peptides were estimated as indicated in Equation (2) (Chen et al. 1974) from the mean residue ellipticity at 222 nm (θ222), averaged over three separate experiments, taking into account the peptide length (n being the number of peptide bonds). No significant concentration dependence of the helical content was observed in the 10–500 μM range.

|

2 |

Determination of the specific side chain interaction energies

Experimental values for specific side chain–side chain interactions were obtained through an adaptation of the double-mutant cycle, in which the helical contents of four peptides are determined and compared. Because the host of the interacting amino acids is a peptide, which adopts multiple conformation (most of them helical segments), measurements are interpreted directly within the framework of the helix/coil transition, using AGADIR (Lacroix et al. 1998). First, a parameter of the helix/coil transition algorithm that is not dependent on amino acid types (e.g., H-bond contribution) is tuned to predict accurately the helical content of the reference peptide (αAA). Second, the intrinsic helical propensities of the amino acids participating in the specific interaction being analyzed are modified to optimize the prediction of the helical content of the intermediate single-residue mutants (e.g., peptides αTA and αAI). Third, the prediction for the double-mutant (e.g., peptide αTI) is refined, adjusting the value of the corresponding specific side chain interaction energy until the right energy balance is established.

Electronic supplemental material

The specific side chain interaction energies calculated by Perla are available as electronic supplemental material.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Maria Macias for the help at the NMR spectrometer, Frank Eisenhaber for assistance with the NSC routine, and Michael Petukhov for discussions and aid with the ECEPP/2 potential. This work has been partly supported by an EU grant (B104-C797–2086).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Supplemental material: See www.proteinscience.org.

Article and publication are at www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.34901.

References

- Andersen, N.H. and Tong, H. 1997. Empirical parameterization of a model for predicting peptide helix/coil equilibrium populations. Protein Sci. 6 1920–1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruch, M.D., Dhingra, M.M., and Gierasch, L.M. 1991. Side chain-backbone hydrogen bonding contributes to helix stability in peptides derived from an alpha-helical region of carboxypeptidase A. Proteins 10 130–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpino, L.A. and Han, G.Y. 1972. The 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl amino-protecting group. J.Organ. Chem. 37 3404–3409. [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabartty, A. and Baldwin, R.L. 1995. Stability of alpha-helices. Adv. Protein Chem./ITL 46 141–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabartty, A., Kortemme, T., Padmanabhan, S., and Baldwin, R.L. 1993. Aromatic side-chain contribution to far-ultraviolet circular dichroism of helical peptides and its effect on measurement of helix propensities. Biochemistry 32 5560–5565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.H., Yang, J.T., and Chau, K.H. 1974. Determination of the helix and beta form of proteins in aqueous solution by circular dichroism. Biochemistry 13 3350–3359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coste, J., Le-Nguyen, D., and Castro, B. 1990. PyBOP: A new peptide coupling reagent devoid of toxic byproducts. Tetrahedron Lett. 31 205–208. [Google Scholar]

- Creamer, T.P. and Rose, G.D. 1995. Interactions between hydrophobic side chains within alpha-helices. Protein Sci. 4 1305–1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahiyat, B.I. and Mayo, S.L. 1996. Protein design automation. Protein Sci. 5 895–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1997. De novo protein design: Fully automated sequence selection. Science 278 82–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahiyat, B.I., Gordon, D.B. and Mayo, S.L. 1997. Automated design of the surface positions of protein helices. Protein Sci. 6 1333–1337. 903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjarlais, J.R. and Handel, T.M. 1995. De novo design of the hydrophobic cores of proteins. Protein Sci. 4 2006–2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doig, A.J., Chakrabartty, A., Klingler, T.M., and Baldwin, R.L. 1994. Determination of free energies of N-capping in alpha-helices by modification of the Lifson–Roig helix-coil therapy to include N- and C-capping. Biochemistry 33 3396–3403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, D. and McLachlan, A.D. 1986. Solvation energy in protein folding and binding. Nature 319 199–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhaber, F., Lijnzaad, P., Argos, P., Sander, C., and Scharf, M. 1995. The double cubic lattice method: Efficient approaches to numerical integration of surface area and volume and to dot surface contouring of molecular assemblies. J. Comp. Chem. 16 273–284. [Google Scholar]

- Fersht, A.R., Matouschek, A. and Serrano, L. 1992. The folding of an enzyme. I. Theory of protein engineering analysis of stability and pathway of protein folding. J. Mol. Biol. 224 771–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill, S.C. and von Hippel, P.H. 1989. Calculation of protein extintion coefficients from aminoacid sequences data. Anal. Biochem. 182 319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huyghues-Despointes, B.M., Klingler, T.M. and Baldwin, R.L. 1995. Measuring the strength of side-chain hydrogen bonds in peptide helices: The Gln.Asp (i, i+4) interaction. Biochemistry 34 13267–13271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehl, P. and Delarue, M. 1994. Application of a self-consistent mean field theory to predict protein side-chains conformation and estimate their conformational entropy. J. Mol. Biol. 239 249–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix, E. 1999. "Protein design: A computer-based approach." Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium.

- Lacroix, E., Viguera, A.R. and Serrano, L. 1998. Elucidating the folding problem of alpha-helices: Local motifs, long-range electrostatics, ionic-strength dependence and prediction of NMR parameters . J. Mol. Biol. 284 173–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazar, G.A., Desjarlais, J.R. and Handel, T.M. 1997. De novo design of the hydrophobic core of ubiquitin. Protein Sci. 6 1167–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifson, R. and Roig, A. 1961. On the theory of helix-coil transitions in biopolymers. J. Chem. Phys. 34 1963–1974. [Google Scholar]

- Lomize, A.L. and Mosberg, H.I. 1997. Thermodynamic model of secondary structure for alpha-helical peptides and proteins. Biopolymers 42 239–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra, G.P. and Wong, C.F. 1997. Predicting helical segments in proteins by a helix-coil transition theory with parameters derived from a structural database of proteins. Proteins 28 344–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momani, F.A., McGuire, R.F., Burgess, A.W. and Scheraga, H.A. 1975. Energy parameters in polypeptides. VII Geometric parameters, partial atomic charges, nonbonded interactions, hydrogen bond interactions, and intrinsic torsional potentials for the naturally occurring amino acids. J. Phys. Chem. 79 2361–2381. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, V. and Serrano, L. 1994a. Elucidating the folding problem of helical peptides using empirical parameters. Nature Struct. Biol. 1 399–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1994b. Intrinsic secondary structure propensities of the amino acids, using statistical phi-psi matrices: Comparison with experimental scales. Proteins 20 301–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemethy, G., Pottle, M.S. and Scheraga, H.A. 1983. Updating of geometrical parameters, nonbonded interactions and hydrogen bond interactions for the naturally occurring amino acids. J. Phys. Chem. 87 1883–1887. [Google Scholar]

- Scholtz, J.M., Qian, H., Robbins, V.H. and Baldwin, R.L. 1993. The energetics of ion-pair and hydrogen-bonding interactions in a helical peptide. Biochemistry 32 9668–9676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapley, B.J. and Doig, A.J. 1997. Hydrogen bonding interactions between glutamine and asparagine in alpha-helical peptides. J. Mol. Biol. 272 465–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street, A.G. and Mayo, S.L. 1998. Pairwise calculation of protein solvent-accessible surface areas. Folding & Design 3 253–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]