Abstract

The NANP repeating sequence of the circumsporozoite protein of Plasmodium falciparum was displayed on the surface of fd filamentous bacteriophage as a 12-residue insert (NANP)3 in the N-terminal region of the major coat protein (pVIII). The structure of the epitope determined by multidimensional solution NMR spectroscopy of the modified pVIII protein in lipid micelles was shown to be a twofold repeat of an extended and non-hydrogen-bonded loop based on the sequence NPNA, demonstrating that the repeating sequence is NPNA, not NANP. Further, high resolution solid-state NMR spectra of intact hybrid virions containing the modified pVIII proteins demonstrate that the peptides displayed on the surface of the virion adopt a single, stable conformation; this is consistent with their pronounced immunogenicity as well as their ability to mimic the antigenicity of their native parent proteins.

Keywords: Peptide epitope, phage display, NMR spectroscopy, malaria, vaccine

Short peptides can be displayed in multiple copies on the surface of filamentous bacteriophages as inserts in the N-terminal region of the major coat protein (pVIII) (Felici et al. 1991; Greenwood et al. 1991; Minenkova et al. 1993; Iannolo et al. 1995). Recombinant virions of bacteriophage fd can be generated with inserts of up to 6–10 amino acids in all 2700 pVIII subunits. Longer peptides can also be displayed, but this requires the creation of hybrid virions in which generally only 5%–30% of the pVIII subunits are modified and contain the inserted residues and the remainder are the 50-residue wild-type protein (Felici et al. 1991; Greenwood et al. 1991; Malik et al. 1996). The physical accessibility of the displayed peptides on the outside of the virions (Terry et al. 1997) is reflected in their high level of immunogenicity (Greenwood et al. 1991; Minenkova et al. 1993). This leads to many potential uses in the exploration of the immune response and vaccine design (Veronese et al. 1994; Perham et al. 1995; De Berardinis et al. 1998). By inserting random DNA sequences into the appropriate positions in the bacteriophage gene encoding pVIII, vast peptide libraries can be constructed (Felici et al. 1991; Smith and Scott 1993). These libraries can then be screened against a given antibody, leading to the isolation of phage virions carrying specific peptides that mimic the original antigen. This technology is highly relevant to epitope mapping as well as drug design (Cortese et al. 1994; Kay et al. 1996; Lowman 1997).

Malaria is a deadly disease, affecting 300 million individuals per year and in equatorial Africa accounting for 50% of child mortality. The human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum has a complex life cycle involving three distinct developmental stages (Smyth 1994). In the first, infective stage, the sporozoite form is injected into the blood stream via a mosquito bite; subsequent stages involve the replication of the merozoite form in the liver and later in the blood (erythrocytes), where the pathology develops. Attempts to produce efficient vaccines at the merozoite stage have had limited success thus far (Fu et al. 1997). On the other hand, some success has been achieved in immunization against the early stage of malarial infection, mostly by targeting the sporozoite (Nardin and Nussenzweig 1993).

The principal protein on the surface of the P. falciparum sporozoite is the 412-residue circumsporozoite (CS) protein. The relevant structural gene has been cloned and sequenced (Dame et al. 1984). Near the middle of the primary structure of the CS protein, 41 tandem repeats of tetrapeptide sequences are found: 37 repeats of the sequence NANP and 4 repeats (units 2, 4, 6, and 22) of the sequence NVDP. Monoclonal antibodies react to this repetitive region and block infection, leading to the conclusion that the main antigenic determinant of the sporozoite is the NANP repeat region (Dame et al. 1984), as described for the corresponding (but different) repeating sequence in the CS protein of Plasmodium knowlesii (Ellis et al. 1983; Godson et al. 1983). Isolated peptides consisting of a large number of copies (16, 32, or 48) of the NANP repeat induce a biologically active immune response in mice (Young et al. 1985), and a promising resistance to malaria has been achieved with a recombinant vaccine embodying the extended repeat region (Stoute et al. 1997). The shorter 12-residue sequence (NANP)3 displayed on hybrid virions of bacteriophage fd is also highly immunogenic (Greenwood et al. 1991). More detailed analyses of related peptide sequences displayed on filamentous bacteriophages also point to the role of this sequence in immunogenicity (Wilson et al. 1997).

We have recently shown that it is possible to use multidimensional solution NMR spectroscopy to determine the structure of a six-residue peptide epitope, GPGRAF, derived from the surface glycoprotein of HIV-1, inserted between residues 3 and 4 in the N-terminal region of the pVIII protein of bacteriophage fd solubilized in lipid micelles (Jelinek et al. 1997). This peptide insert was found to assume a persistent double-turn structure, similar to that adopted by a synthetic peptide of the same sequence when bound to a monoclonal antibody directed against HIV-1 (Ghiara et al. 1994). This was surprising, given the lack of a persistent structure for the free peptide (Chandrasekhar et al. 1991; Zvi et al. 1992; Weliky et al. 1999), but was consistent with the ability of the peptide displayed on bacteriophage virions to elicit HIV-1-neutralizing antibodies in mice (Veronese et al. 1994).

The structure of the antigenic determinant of the CS protein has thus far eluded determination. NMR studies of synthetic peptides containing tandemly repeated tetrapeptide motifs, NANP or NPNA, suggested the presence of helical and/or β-turnlike structures based on the NPNA motif but only in rapid equilibrium with unfolded forms (Dyson et al. 1990). Molecular dynamics simulations of synthetic peptides with a potential β-turn (Bisang et al. 1998) have reinforced the view that the NPNA motif in the CS protein adopts the format of a type-I β-turn. Nonetheless, the actual three-dimensional structure has yet to be established by any experimental technique.

It is possible to use two fundamentally different NMR approaches to determine the structure of the 12-residue peptide (NANP)3 inserted in the N-terminal region of the pVIII protein of bacteriophage fd (Monette et al. 1996). Multidimensional solution NMR spectroscopy can be applied to coat protein monomers containing the epitope solubilized in lipid micelles, as before (Jelinek et al. 1997). The same protein can also be studied by means of solid-state NMR spectroscopy of the intact hybrid virion oriented in the magnetic field of the spectrometer. The results presented here reveal that the structural repeat in the antigenic determinant of the CS protein is a succession of non-hydrogen-bonded loops based on the repeating tetrapeptide NPNA. This strongly reinforces the view that small peptides with a propensity to fold can adopt persistent and biologically relevant structures in the milieu of the N-terminal region of the pVIII protein. This has important implications for our understanding of the structures of continuous epitopes on proteins. Furthermore, it establishes a general approach to determining the structures of peptide epitopes that are typically refractory to conventional experimental methods.

Results

Solution NMR spectroscopy of the epitope in pVIII solubilized in micelles

Multidimensional solution NMR spectroscopy is widely used to determine the structures of soluble globular proteins. The starting point for the experimental measurements that lead to structural parameters, such as short-range distance constraints, is generally a well-resolved two-dimensional heteronuclear correlation spectrum of a uniformly 15N-labeled sample. In this spectrum, each amide nitrogen site contributes a single resonance characterized by 1H and 15N chemical shift frequencies. Subsequently, three-dimensional experiments are used to detect through-bond (TOCSY) and through-space (NOESY) correlations, which enable the assignment of peaks that provide distance constraints. Uniformly 13C- and 15N-labeled protein samples are essential for additional three-dimensional experiments that are valuable for making sequential resonance assignments. pVIII is a hydrophobic membrane protein, which is insoluble when separated from the virion, and can only be studied with solution NMR methods when solubilized in lipid micelles. The three-dimensional structure of the membrane-bound form of the wild-type fd coat protein has been determined with this approach (Almeida and Opella 1997).

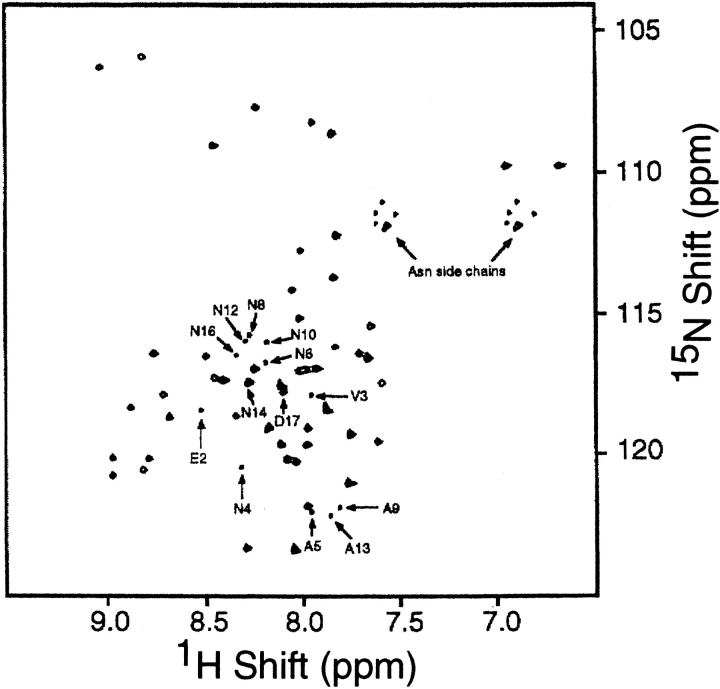

The two-dimensional 1H/15N heteronuclear single quantum correlation (HSQC) spectrum of a mixture of uniformly 15N-labeled wild-type and modified coat proteins containing the (NANP)3 insert, derived from hybrid virions solubilized in lipid micelles, is shown in Figure 1 ▶. The more intense resonances are readily identified and assigned by comparison with the spectrum of the 50-residue wild-type pVIII obtained under similar conditions (Almeida and Opella 1997). The resonances from the amino acid residues in the (NANP)3 epitope and a few neighboring sites in the modified pVIII can be recognized by their lower intensities, because only ∼25% of the polypeptides contain the peptide insert and thus have a total of 62 residues. Nine additional correlation resonances can be identified and assigned to the backbone amide sites of the amino acid residues of the 12-residue peptide insert: three alanine (A5, A9, and A13) and six asparagine (N4, N6, N8, N10, N12, and N14) resonances. Signals from the nitrogens of the three proline residues in the epitope and the one at position 6 in the wild-type protein (position 18 in the modified protein) do not appear in the spectrum because imino nitrogens do not have the attached hydrogens required for magnetization transfer. There are also small backbone amide resonances assigned to asparagine (N16) and a valine (V3) derived from the engineering of the restriction site to allow incorporation of the insert (Greenwood et al. 1991), and two additional neighboring amino acids (E2 and D17) have their resonances slightly shifted from the frequencies found in spectra of the wild-type coat protein. All of the amide resonances are well resolved in the two-dimensional spectrum, except for that from N14 of the modified protein, which was resolved and assigned in a three-dimensional TOCSY–HMQC spectrum.

Fig. 1.

Two-dimensional HSQC spectrum of a mixture of uniformly labeled mutant and wild-type coat proteins in lipid micelles at 35°C. The resonances from residues in the epitope are marked.

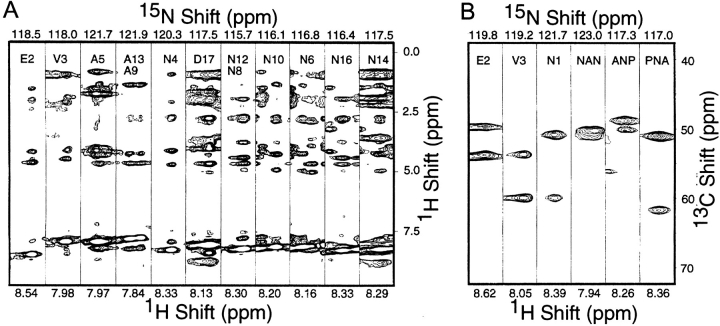

Figure 2A ▶ contains spectral strips from the three-dimensional NOESY–HMQC spectrum of the resonances assigned to the backbone amide sites of the epitope residues in the two-dimensional spectrum in Figure 1 ▶. The intraresidue NOE peaks were identified from the three-dimensional TOCSY–HMQC spectrum. The remaining NOE peaks were assigned to interresidue connectivities, and thus could be used as distance constraints in the structure calculations. The repetitive (NANP)3 sequence made the assignment process difficult using data only from uniformly 15N-labeled samples. However, the results of triple-resonance experiments performed on uniformly 13C- and 15N-labeled samples were able to reduce the number of NOE peaks with ambiguous assignments.

Fig. 2.

(A) Spectral strips extracted from the three-dimensional NOESY–HMQC spectrum of a mixture of uniformly labeled mutant and wild-type coat proteins in lipid micelles at 35°C. The NOE mixing time was 150 msec. (B) Spectral strips extracted from the three-dimensional HNCA spectrum of a mixture of labeled mutant and wild-type coat proteins in SDS micelles at 35°C.

Figure 2B ▶ shows selected strips from a three-dimensional HNCA spectrum (Bax and Ikura 1991). This experiment correlates the 1H and 15N chemical shifts of the amide site with the 13C chemical shifts of the α carbon of the same residue (large peak) and the α carbon of the previous residue (small peak). For example, the strip corresponding to V3 contains two resonances: one larger peak at 60 ppm from the α carbon of V3, and one smaller peak at 54 ppm corresponding to the α-carbon chemical shift of the preceding residue (E2) in the sequence. The repetitive nature of the (NANP)3 sequence rendered even this more powerful approach to making resonance assignments problematic. However, we were able to use the HNCA data to separate the asparagine residues into two different groups based on the chemical shifts of the small α-carbon peaks. An asparagine following the alanine in the NANP motif shows a small peak around 50 ppm, whereas an asparagine following a proline shows a smaller peak around 63 ppm, which is characteristic for the α carbon of proline. The CBCACONH experiment provided complementary information, for the amide resonances are correlated with the α-carbon and β-carbon resonances of the preceding residue. The generally greater dispersion of chemical shifts observed for the β carbons was helpful in confirming many of the assignments.

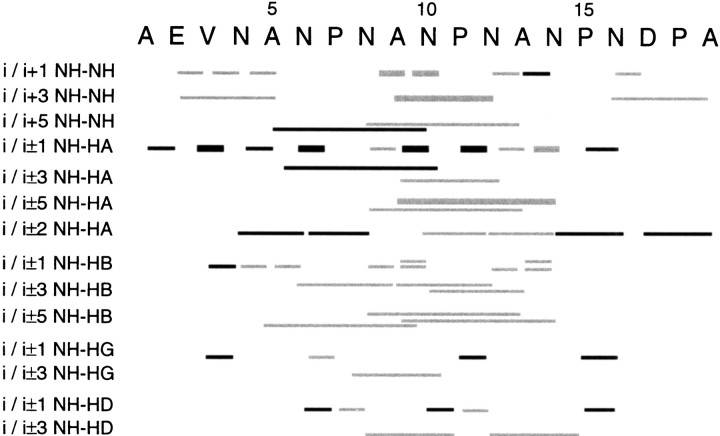

Figure 3 ▶ summarizes the interresidue NOEs extracted from the three-dimensional data shown in Figure 2A ▶. The dark solid lines represent the 19 unambiguously assigned NOEs, and the dotted lines represent the various possibilities for the 17 ambiguously assigned NOEs. A total of 67 constraints were used in the structure calculations performed with the program X-PLOR version 3.1 (Brunger 1992) that incorporates the protocol of Nilges (1995) for dealing with ambiguously assigned NOEs. The upper and lower bounds in the target function were calculated using the sum of all contributing NOEs. Strong, medium, or weak cross-peak intensities were taken to correspond to distance restraints of 1.9–2.7, 1.9–3.3, or 1.9–5 Å, respectively. Upper distance restraints involving methylene and methyl protons were adjusted for center averaging. Initial calculations started from a linear 20-residue peptide. After several iterations, the distances corresponding to the peak intensities were calibrated using sequential NOEs. From the set of 50 structures obtained from the final calculations, 32 had no upper-bound violations of more than 0.1 Å. A subset consisting of the 12 lowest energy structures was selected for further analysis. A steepest-descent minimization of 5000 steps using the CHARMM force field (Brooks et al. 1983) was sufficient to remove bad contacts and reduce the contribution of the Lennard–Jones term to the overall energy.

Fig. 3.

Summary of short-range structure constraints for the NANP epitope residues in coat proteins in lipid micelles.

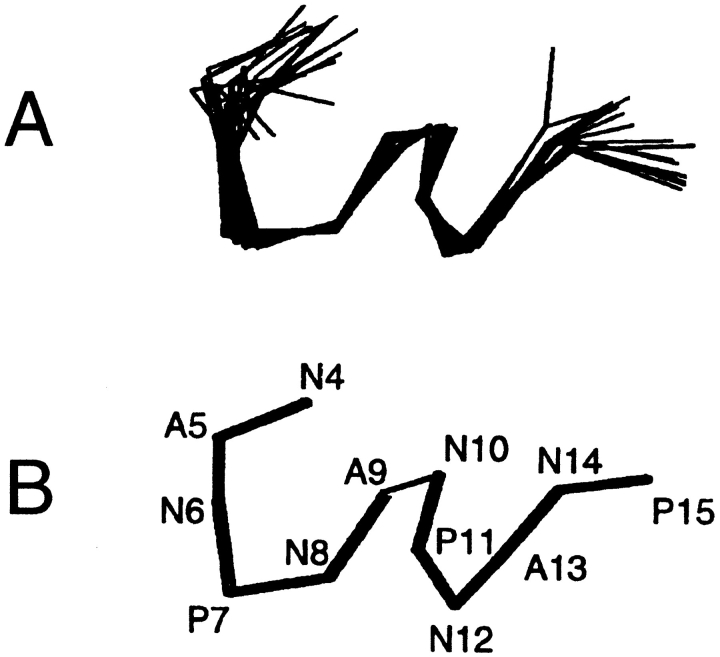

Figure 4A ▶ shows the superposition of the lowest energy structures, and Figure 4B ▶ shows the average structure of the epitope determined from the solution NMR data. The RMSD is <1 Å for the segment N6–N14. The epitope structure consists largely of two extended non-hydrogen-bonded NPNA loops. The α carbon dihedral angle is approximately 10° for the N6–A9 loop and 0° for the N10–A13 loop. These structures were analyzed with PROCHECK (Laskowski et al. 1993). N6 and N8 are in the β-region; and A9, N10, N12, and A13 are in the generous α-region. All the prolines fall in the favored region. The angles for these residues do not fall in the narrower "core" regions of the Ramachandran plots, but are rather distributed in the generously allowed α- and β- regions. This broader nonrepetitive distribution of the amino acids in the Ramachandran plot is typical of loops and turns. The rest of the PROCHECK analysis showed main-chain and side-chain sites well within one standard deviation of the mean. The RMSD for planarity also falls within one standard deviation of the mean. Favorable X1–X2 plots were also obtained for the asparagines, and none of the structures showed bad contacts. The overall G-factor, a measure of the normality of the structure, has an average value of −0.5, indicating good overall geometry. Our results show very clearly that the structurally conserved motif in the epitope is the NPNA tetrapeptide.

Fig. 4.

(A) Superposition of the 12 lowest-energy calculated structures of the NANP epitope in coat proteins in lipid micelles. (B) The average structure obtained from the structures shown in A.

Solid-state NMR spectroscopy of the epitope in pVIII in the bacteriophage virion

Because the intact virion has a total molecular mass of 1.6 × 107 D, the pVIII subunits reorient too slowly for solution NMR methods or instrumentation to be applicable to the virion itself (Opella et al. 1987). The anisotropic (angular-dependent) characteristics of the spin interactions of the 1H and 15N nuclei are directly manifested in the absence of motional averaging, giving very broad and weak signals in solution NMR spectra. In contrast, solid-state NMR methods rely on radiofrequency irradiations and sample orientation to narrow the resonances and enhance the sensitivity in spectra of immobile proteins.

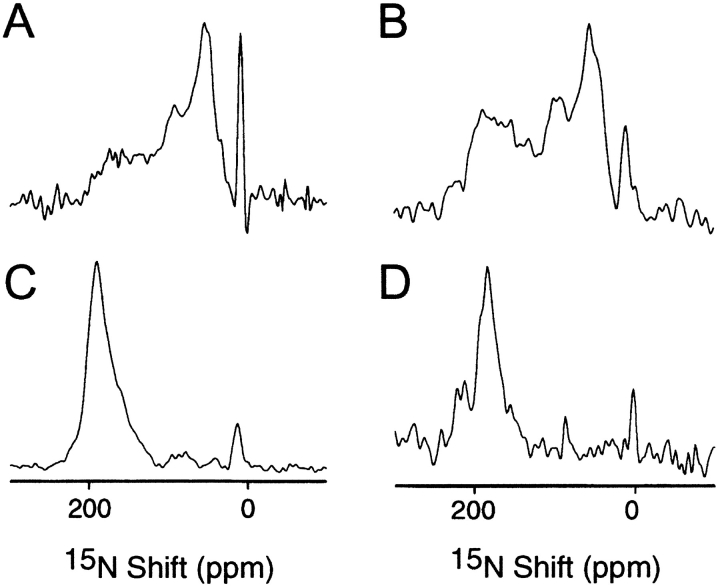

Solid-state NMR experiments were performed on both oriented and unoriented samples of 15N-labeled hybrid bacteriophage virions containing pVIII subunits displaying the (NANP)3 peptide insert. One-dimensional solid-state 15N NMR spectra are shown in Figure 5 ▶. The samples of unoriented virus gave spectra dominated by the characteristic 15N amide chemical shift anisotropy powder pattern. The N-terminal four to five amino acid residues of wild-type pVIII subunits in bacteriophage virions are motionally averaged, leading to a small narrow peak with a resonance frequency near the isotropic position (100 ppm) for amide 15N superimposed on the powder pattern. The N-terminal amino group of pVIII and the side chain amino groups of the five lysine residues give rise to the narrow peak near 10 ppm. When the same sample was oriented in the magnetic field with the long axis of the virion parallel to B0, the spectrum contained a resonance band near 200 ppm. This results from the overlap of 15N resonances with similar frequencies because the NH bonds of the vast majority of residues in the pVIII subunits are aligned approximately parallel to the direction of the applied magnetic field.

Fig. 5.

(A) One-dimensional NMR solid-state NMR spectrum of unoriented uniformly labeled virions containing a mixture of mutant and wild-type coat proteins. (C) Same as A, except the virions are oriented in the magnetic field of the NMR spectrometer. (B) Same as A, except that the sample was selectively labeled with Asn. (D) Same as B, except that the sample was selectively labeled with Asn.

The spectra in Figures 5A and 5B ▶ are similar to those obtained and analyzed previously from bacteriophage samples containing only wild-type pVIII (Cross and Opella 1983; Jelinek et al. 1995; Tan et al. 1999). Extra resonances from the amino acid residues in the peptide insert are difficult to identify in these spectra, because they are weak and overlap with wild-type resonances. Selective 15N labeling of the asparagine residues was particularly helpful, since wild-type pVIII contains no asparagine. The modified pVIII subunits containing the (NANP)3 insert have seven asparagine residues, of which six are in the epitope and one (derived from the cloning site) follows immediately at position 16. The spectrum in Figure 5C ▶ is from an unoriented phage sample selectively 15N-labeled at the backbone amide sites of the seven asparagine residues. The dominant powder pattern line shape indicates that all or nearly all of the residues in the insert are immobile on the timescale of the 15N chemical shift interaction (104 Hz). This is a crucial finding. It means that the peptide epitope is structured in the context of the N-terminal region of the coat protein, and is immobilized along with the bulk of the coat protein. This contrasts with the finding that the N-terminal residues of wild-type coat protein are mobile, and give isotropic resonance intensity. Furthermore, the NMR spectrum of the oriented 15N-Asn-labeled sample (Fig. 5D ▶) demonstrates that the asparagine residues are uniformly oriented along with the virus particles in the magnetic field of the spectrometer. This means that each copy of the epitope has the same conformation and that the three-dimensional structure can potentially be determined by solid-state NMR spectroscopy of oriented samples (Opella et al. 1987). The large peak near 190 ppm indicates that most of the asparagine backbone N–H bonds are approximately parallel to the long axis of the virion and the direction of the applied magnetic field. The first asparagine residue in the peptide insert might have some mobility, as suggested by the small peak at 100 ppm in the spectrum of the oriented sample (Fig. 5D ▶), and a hint of isotropic intensity superimposed on the powder pattern at the same frequency (Fig. 5C ▶). For technical reasons it is difficult to quantitate resonance intensities from mobile or partially mobile residues.

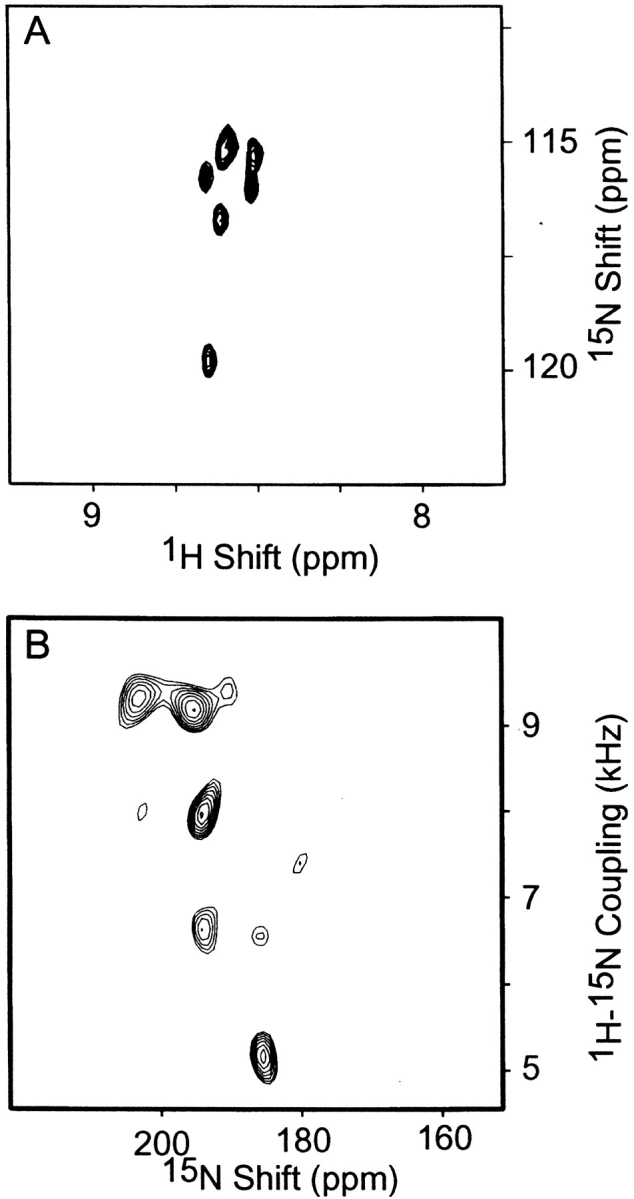

Because selective isotopic labeling in bacterial cultures can result in significant amounts of cross labeling, which in turn can lead to extra resonances in the spectra, control experiments are essential. Figure 6A ▶ shows the two-dimensional 1H/15N HMQC spectrum of selectively 15N-Asn-labeled pVIII proteins in SDS micelles that were isolated from the same preparation of virions used to obtain the solid-state NMR spectra shown in Figure 5 ▶. The resonances in the spectrum in Figure 6A ▶ are superimposable on those assigned to individual asparagine residues in the spectrum of uniformly 15N-labeled coat protein shown in Figure 1 ▶. Even at the baseline noise level of the spectrum, additional peaks are not detectable, indicating that a negligible amount of cross labeling had occurred. This sample contributes crucial and highly reliable data, because the labeled sites are exclusively in the modified pVIII. A two-dimensional polarization inversion spin exchange at the magic angle (PISEMA) spectrum (Wu et al. 1994; Jelinek et al. 1995) of selectively 15N-Asn-labeled hybrid virions oriented in the magnetic field is shown in Figure 6B ▶. Each amide resonance in a PISEMA spectrum is characterized by a 15N chemical shift frequency and a 1H–15N heteronuclear dipolar coupling frequency, both of which vary with the orientation of the peptide plane with respect to the direction of the applied magnetic field. The spectrum in Figure 6B ▶ has five peaks that are well resolved and have good line shapes in both frequency dimensions. This is possible only if the residues are in a single conformation for the length of the experiment. It is likely that the Asn residue nearest the N terminus of the modified pVIII protein, N4, contributes an isotropic 15N resonance that does not appear in this spectrum. One other resonance needs to be accounted for, and it may be the smaller peak near 185 ppm and 9.5 kHz, or it may overlap with one of the five large resonances. Because each resolved resonance in Figure 6B ▶ is characterized by unique chemical shift and dipolar coupling frequencies, the spectroscopic parameters can be translated into angles (α and β) defining the orientation of the peptide plane with respect to the direction of the applied magnetic field (Opella et al. 1987). The finding of specific orientations consistent with the experimental solid-state NMR data is very strong evidence that the residues in the epitope are immobile and uniquely oriented when displayed on the surface of the virion.

Fig. 6.

(A) Two-dimensional HMQC spectrum of a sample containing a mixture of mutant and wild-type coat proteins selectively labeled with Asn. (B) Two-dimensional PISEMA spectrum of an oriented phage sample containing a mixture of mutant and wild-type coat proteins selectively labeled with Asn.

Discusssion

Many proteins contain continuous peptide epitopes of five or six or more amino acid residues, in addition to the nonsequential or conformational antigenic determinants brought about by the three-dimensional folding of a protein (Laver et al. 1990; Arnon and van Regenmortel 1992). However, when a continuous epitope has been identified, it generally resists structural analysis in aqueous solution because of the lack of persistence in its three-dimensional structure typical of small peptides (Dyson and Wright 1991). It was therefore remarkable that a six-residue peptide GPGRAF, which forms an immunodominant epitope of the surface glycoprotein gp120 of HIV-1, should exhibit a persistent structure when inserted in the N-terminal region of the pVIII of filamentous bacteriophage fd (Jelinek et al. 1997). It was also remarkable that the structure of the peptide, established by means of solution NMR spectroscopy of the modified pVIII protein solubilized in lipid micelles, should so closely resemble that of a peptide of identical sequence in a complex with a monoclonal antibody directed against the native gp120 (Ghiara et al. 1994; Weliky et al. 1999). This indicated that the structure adopted by the peptide insert in pVIII is likely to be biologically relevant and similar to that in the native parent protein.

Here we show that a second continuous peptide epitope, the NANP repeating sequence of the CS protein of P. falciparum (Dame et al. 1984), also has a persistent structure when inserted in pVIII. The inserted sequence, (NANP)3, was selected because it represented three repeats of the NANP tetrapeptide. However, the structure derived from multidimensional NMR spectroscopy of the modified pVIII in lipid micelles is revealed as a twofold repeat of an extended and non-hydrogen-bonded loop based on the sequence NPNA. This unequivocally demonstrates that the repeating motif is NPNA, not NANP, as suspected from NMR studies of synthetic peptides (Dyson et al. 1990), molecular dynamics simulations (Nanzer et al. 1997), and an analysis of the structures of similar peptides (Wilson and Finlay 1997) including in the context of immunogenicity when displayed on filamentous bacteriophage (Wilson et al. 1997). The structure is wholly different from the double-turn structure adopted by the GPGRAF epitope (Jelinek et al. 1997) and therefore cannot be regarded as an artifactual folding imposed by the pVIII host environment. It is reasonable to suppose that the structure we have described is similar to that adopted by the repeating sequence in the native CS protein. Our results make it clear that different peptide inserts can take up different structures dictated presumably by their own propensity to fold, suggesting that the N-terminal region of pVIII is a sympathetic environment for peptide folding.

The experiments on the intact hybrid virion displaying the (NANP)3 epitope demonstrate that it should be possible to determine the structure of the epitope directly by means of solid-state NMR spectroscopy. This would be an additional major step forward in the technology. What can be inferred already is that the displayed peptide has a defined structure, though whether it the same as that established for the micelle form remains to be established. However, it is obvious that peptides displayed on the surface of the virion can and do fold up in single, stable conformations. This is consistent with their pronounced immunogenicity as well as their ability to mimic the antigenic determinants of their native parent proteins (Greenwood et al. 1991; Veronese et al. 1994). It also adds weight to the view that their bulk after folding may be a major factor in preventing large peptides from being displayed on all 2700 copies of pVIII in a recombinant virion, since they would then render the diameter of the virion too large to pass through the trans-membrane pore of bacteriophage pIV proteins created for viral egress from the infected bacterial cell (Kazmierczak et al. 1994; Russel 1994; Malik et al. 1998).

The structure of the GPGRAF antigenic determinant of HIV-1 (Jelinek et al. 1997) has assumed a particular interest, in view of the fact that the V3 loop is one of several variable regions of the gp120 molecule that were deliberately excised in the creation of the core fragment whose crystal structure was solved in a complex with two immunogobulinlike domains from the CD4 receptor and an antibody fragment (Kwong et al. 1998). The V3 loop is therefore missing from the structure and, given its variability and potential for conformational flexibility, is unlikely to be well resolved in any further attempt to solve a crystal structure of gp120. Likewise, the curious and highly repetitive NANP sequence, together with the repetitive turn structure we have determined in the antigenic determinant of the P. falciparum CS protein, strongly suggest that it cannot form part of a conventional globular protein. This is likely to hinder or even prevent crystallization of the protein for X-ray diffraction, and the intact protein is too big to tackle by NMR spectroscopy. Similarly, the highly antigenic G–H loop region of the VPI protein of foot-and-mouth disease virions (FMDV) forms a protruding surface loop, too disordered to be seen in the X-ray crystallographic structure (Acharya et al. 1989). Nor does it adopt a persistent structure as an isolated synthetic peptide, as judged by NMR spectroscopy (de Prat-Gay 1997). However, it does become sufficiently ordered for X-ray analysis after chemical reduction of a disulfide bridge at the base of the loop in the intact virus crystal; it then assumes a turn/310-helix motif that is stabilized by its snuggling in a minor surface depression (Logan et al. 1993). When the same peptide is inserted in pVIII in a hybrid bacteriophage virion, it adopts a similar turn/helix conformation, as determined by the multidimensional NMR technologies described above, without the need for additional stabilization (unpublished results).

In light of our general knowledge of proteins and the structures of the three continuous epitopes that we have now solved (Jelinek et al. 1997; this work; unpubl.), we think it likely that many, if not all, such epitopes will consist of one or more exposed turns of various kinds coupled with other secondary structure motifs that differ from peptide sequences whose folding is defined by the local primary structure. They will generally be too exposed and conformationally flexible to be determined by X-ray crystallography, and they will probably lack persistent structure in solution as synthetic peptides. However, the capacity to adopt their natural structure, or something closely approaching it, when inserted in the N-terminal region of the pVIII of filamentous bacteriophage fd opens up a vital new strategy for determining the structure of such antigenic determinants. The importance for improving our understanding of the fundamental molecular basis of antigenicity and its exploitation in vaccine design is clear.

Materials and methods

Expression and purification of hybrid virions

A gene encoding a modified pVIII protein that contains the 12 extra amino acids of the (NANP)3 inserted between residues 3 and 4 was overexpressed from plasmid pKfdMAL1 (Greenwood et al. 1991) in Escherichia coli cells. The cells were grown at 37° C in minimal M9 medium containing (15NH4)2SO4 (1 g/L) (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Woburn, MA). For the uniformly 13C- and 15N-labeled sample, 13C-labeled glucose (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories) was added to the medium (4 g/L) as the only source of carbon. Protein selectively labeled with 15N-alanine was obtained by growing the cells in a M10 medium containing 15N-alanine (Isotec, Miamisburg, OH), (14NH4)2SO4, and unlabeled valine, leucine, isoleucine, and threonine (100 mg/L). 15N-amino-labeled asparagine (Isotec) (100 mg/L) was added to the usual minimal medium to prepare the selectively 15N-asparagine-labeled protein. When the culture reached an A600 of 0.4, the temperature was decreased to 30° C and the synthesis of the modified protein was induced by the addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of approximately 1 mM. After 1 h of induction, the cells were infected with wild-type bacteriophage fd and grown for an additional 7–12 h. Hybrid virions were produced in high yield (20–30 mg/L) and isolated by polyethylene glycol precipitation, followed by KBr gradient centrifugation (Malik et al. 1996). The ratio of modified to wild-type coat protein in the viral capsid was approximately 1 : 4, as judged by SDS-PAGE (Greenwood et al. 1991).

Solution NMR experiments

The labeled coat proteins (mutant and wild-type) were solubilized by adding SDS to a dilute suspension of hybrid phage virions with a total concentration of 2 mM. Typical samples contained a mixture of modified and wild-type pVIII proteins, 480 mM d25-sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS) (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories) and 40 mM NaCl at pH 4. The solutions were briefly centrifuged before transfer to NMR sample tubes. All solution NMR experiments were performed at 35° C on a Bruker (Bruker Instruments, Billerica, MA) DMX-750 NMR spectrometer with a triple-resonance, triple-gradient 5-mm probe. Suppression of the water resonance was accomplished with the WATERGATE (Sklenar et al. 1993) sequence before data acquisition. Data were processed with XWIN-NMR (Bruker Instruments) and analyzed using NMRCOMPASS (MSI, San Diego, CA).

Two-dimensional HMQC spectra were acquired with 128 increments in the 15N dimension, and 16 transients were co-added with a recycle delay of 1.5 or 2 sec. Time-proportional phase-sensitive incrementation (TPPI) was used for quadrature detection. The spectra were processed with exponential multiplication in the 1H dimension and sine bell multiplication in the 15N dimension. The final data matrix had 2048 × 256 points.

Two-dimensional HSQC spectra were obtained with 512 increments in the 15N dimension and 64 transients, and TPPI detection. Exponential and sine bell functions were applied as well. The final data matrix contained 4096 × 1024 points.

The three-dimensional HMQC–NOESY experiment was performed with a mixing time of 150 msec. The spectrum was acquired with 64 increments in the 15N dimension, 128 increments in the 1H indirect dimension, and 16 transients collected using the States–TPPI detection method. The data were processed with exponential multiplication in the 1H direct dimension and sine bell multiplication in the 1H indirect and 15N dimensions. The size of the final transformed matrix was 1024 × 256 × 128 points. All spectra are referenced internally to the residual 1H2O resonance at 4.75 ppm and externally to liquid ammonia (0 ppm). The three-dimensional HNCA (Bax and Ikura 1991) spectrum was obtained with 64 increments in both 15N and 13C dimensions, and 48 transients were collected using the States–TPPI detection method. The data were processed with exponential multiplication in the 1H direct dimension and sine bell multiplication in the 13C indirect dimension as well as the 15N dimension. In the 13C dimension, complex linear prediction was applied to 128 points (64 acquired points and 64 predicted points). After Fourier transformation, the size of the matrix was 1024 × 128 × 128 points.

Solid-state NMR experiments

The solid-state NMR experiments were performed on suspensions of bacteriophage virions. The concentrated gel obtained by ultracentrifugation (50,000 rpm for 2 h) was resuspended in sodium borate buffer (5 mM at pH 8.0) and diluted to 50 mg/mL to enable spontaneous orientation of the virions in the magnetic field. The spectra were acquired on home-built spectrometers with magnetic fields corresponding to 1H resonance frequencies of 550 and 700 MHz. The probes had solenoid coils of 5 mm or 7 mm I.D. double-tuned to the 1H and 15N resonance frequencies.

The one-dimensional spectra were obtained with a phase-cycled cross-polarization sequence in which the 90° pulse length was 4 μsec and the cross-polarization mixing time was 1 msec. A recycle delay greater than 5 sec was used to avoid heating the sample. For each spectrum 102–104 transients were signal-averaged. Exponential multiplication and zero filling to 512 points were performed before Fourier transformation.

The two-dimensional PISEMA spectra were acquired with 32–64 increments in the dipolar dimension, 102–103 transients, and a recycle delay of 5–7 sec. The data were processed with the FELIX program (MSI). Exponential multiplication in the 15N dimension, Gaussian multiplication in the 1H–15N dipolar coupling dimension, and zero-filling to 512 points were performed before Fourier transformation.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Mesleh for helpful discussions. This research was supported by grant R37 GM24266 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and by the Wellcome Trust. It utilized the Resource for Solid-State NMR of Proteins supported by grant P41RR09731 from the Biomedical Research Technology Program, National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health. M. Monette was supported by a Medical Research Council of Canada postdoctoral fellowship, and J. Greenwood was supported by a Lloyds of London Tercentenary Foundation Fellowship.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.35901.

References

- Acharya, R., Fry, E., Stuart, D., Graham, F., Rowlands, D., and Brown, F. 1989. The three-dimensional structure of foot-and-mouth disease virus at 2.9 Å resolution. Nature 337 709–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, F.C.L. and Opella, S.J. 1997. fd coat protein structure in membrane environments: Structural dynamics of the loop between the hydrophobic trans-membrane helix and the amphipathic in-plane helix. J. Mol. Biol. 270 481–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnon, R. and van Regenmortel, M. 1992. Structural basis of antigenic specificity and design of new vaccines. FASEB J. 6 3265–3274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bax, A. and Ikura, M. 1991. An efficient 3D NMR technique for correlating the proton and 15N backbone amide resonance with the α-carbon of the preceding residue in uniformly 15N/13C enriched proteins. J. Biomol. NMR 1 99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisang, C., Weber, C., Inglis, J. Schiffer, C.A., van Gunsteren, W.F., Jelesarov, I., Bosshard, H.R., and Robinson, J.A. 1998. Stabilization of type-I β-turn conformations in peptides containing the NPNA-repeat motif of the Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein by substituting proline for (S)-α-methylproline. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120 7439–7444. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, B.R., Bruccoleri, R.E., Olafson, B.D., States, D.J., Swaminathan, S., and Karplus, M. 1983. CHARMM: A program for macromolecular energy minimization and dynamics calculations: J. Comp. Chem. 4 187–217. [Google Scholar]

- Brunger, A.T. 1992. X-PLOR 3.1: A system for X-ray crystallography and NMR. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

- Chandrasekhar, K., Profy, A.T., and Dyson, H.J. 1991. Solution conformational preferences of immunogenic peptides derived from the principal neutralizing determinant of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp120. Biochemistry 30 9187–9194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortese, R., Felici, F., Galfre, G., Luzzago, A., Monaci, P., and Nicosia, A. 1994. Epitope discovery using peptide libraries displayed on phage. Trends Biotechnol. 12 262–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross, T.A. and Opella, S. J. 1983. Protein structure by solid-state NMR. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 105: 306–308. [Google Scholar]

- Dame, J.B., Williams, J.L., McCutchan, T.F., Weber, J.L., Wirtz, R.A., Hockmeyer, W.T., Maloy, W.L., Haynes, J.D., Schneider, I., Roberts, D., et al. 1984. Structure of the gene encoding the immunodominant surface antigen on the sporozoite of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Science 225 593–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Berardinis, P., D'Apice, L., Prisco, A., Ombra, M.N., Barba, P., Del Pozzo, G., Petukhov, S., Malik, P., Perham, R.N., and Guardiola, J. 1998. Recognition of HIV-derived B and T cell epitopes displayed on filamentous phages. Vaccine 17 1434–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Prat-Gay, G. 1997. Conformational preferences of a peptide corresponding to the major antigenic determinant of foot-and-mouth disease virus: Implications for peptide–vaccine approaches. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 341 360–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson, H.J. and Wright, P.E. 1991. Defining solution conformations of small linear peptides. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Chem. 20: 519–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson, H.J., Satterthwait, A.C., Lerner, R.A., and Wright, P.E. 1990. Conformational preferences of synthetic peptides derived from the immunodominant site of the circumsporozoite protein of Plasmodium falciparum by 1H NMR. Biochemistry 29 7828–7837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, J., Ozaki, L.S., Gwadz, R.W., Cochrane, A.H., Nussenzweig, V., Nussenzweig, R.S., and Godson, G.N. 1983. Cloning and expression in E. coli of the malarial sporozoite surface antigen gene from Plasmodium knowlesii. Nature 302 536–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felici, F., Castagnoli, L., Musacchio, A., Jappelli, R., and Cesareni, G. 1991. Selection of antibody ligands from a large library of oligopeptides expressed on a multivalent exposition vector. J. Mol. Biol. 222 301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y., Shearing, L.N., Haynes, S., Crewther, P., Tilley, L., Anders, R.F., and Foley, M. 1997. Isolation from phage display libraries of single chain variable fragment antibodies that recognize conformational epitopes in the malaria vaccine candidate, apical membrane antigen-1. J. Biol. Chem. 272 25678–25684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiara, J.B., Stura, E.A., Stanfield, R.L., Profy, A.T., and Wilson, I.A. 1994. Crystal structure of the principal neutralization site of HIV-1. Science 264 82–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godson, G.N., Ellis, J., Svec, P., Schlesinger, D.H., and Nussenzweig, V. 1983. Identification and chemical synthesis of a tandemly repeated immunogenic region of Plasmodium knowlesii circumsporozoite protein. Nature 305 29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, J., Willis, A.E., and Perham, R.N. 1991. Multiple display of foreign peptides on a filamentous bacteriophage. J. Mol. Biol. 220 821–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannolo, G., Minenkova, O., Petruzzelli, R., and Cesareni, G. 1995. Modifying filamentous phage capsid: Limits in the size of the major capsid protein. J. Mol. Biol. 248 835–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelinek, R., Ramamoorthy, A., and Opella, S.J. 1995. High-resolution three-dimensional solid-state NMR spectroscopy of a uniformly 15N-labeled protein. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 117 12348–12349. [Google Scholar]

- Jelinek, R., Terry, T.D., Gesell, J.J., Malik, P., Perham, R. N., and Opella, S.J. 1997. NMR structure of the principal neutralizing determinant of HIV-1 displayed in filamentous bacteriophage coat protein. J. Mol. Biol. 266 649–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay, B.K., Winter, J., and McCafferty, J., eds. 1996. Phage display of peptides and proteins. A laboratory manual. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- Kazmierczak, B., Mielke, D., Russel, M., and Model, P. 1994. Filamentous phage pIV forms a multimer that mediates phage export across the bacterial cell envelope. J. Mol. Biol. 238 187–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong, P.D., Wyatt, R., Robinson, J., Sweet, R.W., Sodroski, J., and Hendrickson, W.A. 1998. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature 393 648–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski, R.A., MacArthur, M.W., Moss, D.S., and Thornton, J.M. 1993. PROCHECK: A program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structure. J. Appl. Cryst. 26 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Laver, W.G., Air, G.M., Webster, R.G., and Smith-Gill, S.J. 1990. Epitopes on protein antigens: Misconceptions and realities. Cell 61 553–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan, D., Abu-Ghazaleh, R., Blakemore, W., Curry, S., Jackson, T., King, A., Lea, S., Lewis, R., Newman, J., Parry, N., et al. 1993. Structure of a major immunogenic site on foot-and-mouth disease virus. Nature 362 566–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowman, H.B. 1997. Baceriophage display and discovery of peptide leads for drug development. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 26 401–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik, P., Terry, T.D., Gowda, L.R., Langara, A., Petukhov, S.A., Symmons, M.F., Welsh, L.C., Marvin, D.A., and Perham, R.N. 1996. Role of capsid structure and membrane protein processing in determining the size and copy number of peptides displayed on the major coat protein of filamentous bacteriophage. J. Mol. Biol. 260 9–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik, P., Terry, T.D., Bellintani, F., and Perham, R.N. 1998. Factors limiting display of foreign peptides on the major coat protein of filamentous bacteriophage capsids and a potential role for leader peptidase. FEBS Lett. 436 263–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minenkova, O.O., Ilyichev, A.A., Kischenko, G.P., and Petrenko, V.A. 1993. Design of specific immunogens using filamentous phage as the carrier. Gene 128 85–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monette, M., Gratkowski, H., Opella, S.J., Greenwood, J., Willis, A.E., and Perham, R.N. 1996. Initial characterization of a peptide epitope displayed on the surface of fd bacteriophage by solution and solid-state NMR spectroscopy. In Techniques in Protein Chemistry VII, pp. 121–129. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- Nanzer, A.P., Torda, A.E., Bisang, C., Weber, C., Robinson, J.A., and van Gunsteren, W.F. 1997. Dynamical studies of peptide motifs in the Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite surface protein by restrained and unrestrained MD simulations. J. Mol. Biol. 267 1012–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardin, E.H. and Nussenzweig, R.S. 1993. T cell responses to pre-erythrocytic stages of malaria: Role in protection and vaccine development against pre-erythrocytic stages. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 11 687–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilges, M. 1995. Calculation of protein structures with ambiguous restraints. Automated assignments of ambiguous NOE cross-peaks and disulfide connectivities. J. Mol. Biol. 245 645–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opella, S.J., Stewart, P.L., and Valentine, K.G. 1987. Protein structure by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Quart. Rev. Biophys. 19 7–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perham, R. N., Terry, T. D., Willis, A.E., Greenwood, J., di Marzo Veronese, F., and Appella, E. 1995. Engineering a peptide epitope display system on filamentous bacteriophage. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 17 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russel, M. 1994. Mutants at conserved positions in gene IV, a gene required for assembly and secretion of filamentous phage. Mol. Microbiol. 14 357–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sklenar, V., Piotto, M., Leppik, R., and Saudek, V. 1993. Gradient-tailored water suppression for 1H–15N HSQC experiments optimized to retain full sensitivity. J. Magn. Reson. A 102 241–245. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G.P. and Scott, J.K. 1993. Libraries of peptides and proteins displayed on filamentous phage. Methods Enzymol. 217 228–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth, J.D. 1994. Introduction to animal parasitology, 3rd ed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Stoute, J.A., Slauoui, M., Heppner, D.G., Momin, P., Kester, K.E., Desmons, P., Wellde, B.T., Garcon, N., Krzych, U., and Marchand, M. 1997. A preliminary evaluation of a recombinant circumsporozoite protein vaccine against Plasmodium falciparum malaria. New Eng. J. Med. 336 86–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, W.M., Jelinek, R., Opella, S.J., Malik, P., Terry, T.D., and Perham, R.N. 1999. Effects of temperature and Y21M mutation on conformational heterogeneity of the major coat protein (pVIII) of filamentous bacteriophage fd. J. Mol. Biol. 286 787–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry, T.D., Malik, P., and Perham, R.N. 1997. Accessibility of peptides displayed on filamentous bacteriophage virions: Susceptibility to proteinases. J. Biol. Chem. 378 523–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veronese, F.D.M., Willis, A.E., Boyer-Thompson, C., Appella, E., and Perham, R. N. 1994. Structural mimicry and enhanced immunogenicity of peptide epitopes displayed on filamentous bacteriophage. J. Mol. Biol. 243 167–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weliky, D.P., Bennett, A.E., Zvi, A., Anglister, J., Steinbach, P.J., and Tycko, R. 1999. Solid-state NMR evidence for an antibody-dependent conformation of the V3 loop of HIV-1 gp120. Nature Structural Biology 6 141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, D.R. and Finlay, B.B. 1997. The `Asx–Pro turn' as a local structural motif stabilized by alternative patterns of hydrogen bonds and a consensus-derived model of the sequence Asn–Pro–Asn. Protein Engineering 10 519–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, D.R., Wirtz, R.A., and Finlay, B.B. 1997. Recognition of phage-expressed peptides containing Asx–Pro sequences by monoclonal antibodies produced against Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein. Protein Engineering 10 531–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.H., Ramamoorthy, A., and Opella, S.J. 1994. High-resolution heteronuclear dipolar solid-state NMR spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. A 109 270–272. [Google Scholar]

- Young, JF., Hockmeyer, W.T., Gross, M., Ballou, W.R., Wirtz, R.A., Trosper, J.H., Beaudoin, R.L., Hollingdale, M.R., Miller, L.H., Diggs, C.L., et al. 1985. Expression of Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite proteins in Escherichia coli for potential use in a human malaria vaccine. Science 228 958–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvi, A., Hiller, R., and Anglister, J. 1992. Solution conformation of a peptide corresponding to the principal neutralizing determinant of HIV-IIIB: A two-dimensional NMR study. Biochemistry 31 6972–6979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]