Abstract

The yeast cell adhesion protein α-agglutinin is expressed on the surface of a free-living organism and is subjected to a variety of environmental conditions. Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy shows that the binding region of α-agglutinin has a β-sheet-rich structure, with only ∼2% α-helix under native conditions (15–40°C at pH 5.5). This region is predicted to fold into three immunoglobulin-like domains, and models are consistent with the CD spectra as well as with peptide mapping and site-specific mutagenesis. However, secondary structure prediction algorithms show that segments comprising ∼17% of the residues have high α-helical and low β-sheet potential. Two model peptides of such segments had helical tendencies, and one of these peptides showed pH-dependent conformational switching. Similarly, CD spectroscopy of the binding region of α-agglutinin showed reversible conversion from β-rich to mixed α/β structure at elevated temperatures or when the pH was changed. The reversibility of these changes implied that there is a small energy difference between the all-β and the α/β states. Similar changes followed cleavage of peptide or disulfide bonds. Together, these observations imply that short sequences of high helical propensity are constrained to a β-rich state by covalent and local charge interactions under native conditions, but form helices under non-native conditions.

Keywords: Cell adhesion protein, circular dichroism, conformational shift, glycoprotein, peptide conformation, secondary structure prediction

α-Agglutinin is a glycoprotein expressed on the cell surface of mating-type α cells in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. It is involved in mediating cellular adhesion during mating between haploid α and a cells through an interaction with its glycoprotein ligand a-agglutinin (Hauser and Tanner 1989; Lipke and Kurjan 1992). The carboxy-terminal half of α-agglutinin anchors the protein to the cell wall (Wojciechowicz et al. 1993; Lu et al. 1994, 1995; Kapteyn et al. 1996), and the amino-terminal half contains the binding site for a-agglutinin (Wojciechowicz et al. 1993; Chen et al. 1995; Lipke et al. 1995; Grigorescu et al. 2000).

The amino-terminal half of α-agglutinin encompasses residues 20–351, is β-sheet-rich, and has full binding activity (Wojciechowicz et al. 1993; Chen et al. 1995). This region has structural and sequence properties similar to members of the immunoglobulin (Ig) superfamily, including disulfide-bonded Cys residues in Ig-like sequence motifs (Wojciechowicz et al. 1993; Chen et al. 1995; Lipke et al. 1995; Grigorescu et al. 2000). On the basis of secondary structure studies, peptide mapping, and "homology" modeling, this region is proposed to consist of three tandem Ig-like domains (Wojciechowicz et al. 1993; Grigorescu et al. 2000). Of these, domain III (residues 190–325) is essential for function, because truncation of the AGα1 gene at amino acid 278 eliminates the proposed E, F, and G strands in domain III of α-agglutinin20–351 and all of its binding activity (Wojciechowicz et al. 1993; Grigorescu et al. 2000). Chemical modification and site-specific mutagenesis have identified residues in domain III that are important for the binding of α-agglutinin20–351 to a-agglutinin (Cappellaro et al. 1991; Wojciechowicz et al. 1993; de Nobel et al. 1996). Domains I and II may also be essential for α-agglutinin to function: partial deletions within either domain inactivate the protein, and domain III alone has no measurable activity (Wojciechowicz 1990; Chen et al. 1995). α-Agglutinin binds its glycoprotein ligand a-agglutinin, expressed on the surface of cells of mating-type a. Binding is tight, with a Kd near 10−9 M and an extremely slow dissociation rate (Lipke et al. 1987; Lipke and Kurjan 1992; Zhao 1999; Zhao et al. 2001).

α-Agglutinin differs from other members of the Ig superfamily in a number of ways (Williams and Barclay 1988; Baldwin et al. 1993). Most proteins in the superfamily are maximally active at pH values near 7.0 and temperatures near 37°C, the mammalian homeostatic conditions. In contrast, α-agglutinin is most active at pH 5–6, and it is inactive at pH below 3.0 or above 9.0 (Terrance and Lipke 1981). α-Agglutinin is active at temperatures between 15° and 40°C, but the activity is reduced at 10°C and is lost within 10 min at 55°C. Controversially, Yamaguchi and colleagues showed that α-agglutinin is stable and still active even after 5 min of autoclaving (Yamaguchi et al. 1982). Moreover, a number of sequences in α-agglutinin20–351 are strongly predicted to be in α-helical conformation (Table 1). This is unusual for Ig-like proteins, which are composed of β-sandwich domains, with interior hydrophobic cores often stabilized by disulfide bonds (Williams and Barclay 1988).

Table 1.

Sequences in α-agglutinin with high helical potential

| Residues | Position in model (domain: strands)a | Helical potentialb | Charge stabilizationc | Commentsd |

| 52–55 | I: C` strand | CF++ GR++ E | ||

| 89–96 | I: F strand | CF++ GR++ HNN E | + | Near disulfide; helicity increases upon reduction. |

| 99–103 | I: F-G loop | CF++ GR++ JPRED HNN | Near disulfide; helicity increases upon reduction. | |

| 143–154 | II: C strand, C-C` loop, C` strand | CF++ GR+++ JPRED HNN PHD | + | Helicity increases following cleavage at Lys154. Model peptide I is helical at pH3 and pH7, strand-like at pH5. |

| 174–181 | II: F-G loop | CF+ GR++ HNN E SW | ||

| 264–268 | III: C-C` loop | CF++ GR+ HNN PHD | ||

| 271–274 | III: C"-D loop | CF++ GR+ HNN | + | |

| 276–280 | III: D strand | CF+ JPRED HNN | ||

| 290–296 | III: E-F loop | CF++ GR+ HNN | + | Near disulfide; helicity increases upon reduction; Close to binding region; model peptide II is helical. |

a Predicted position in Ig-like model of α-agglutinin domains: domain number and strand assignment (Lipke et al. 1995; Grigorescu et al. 2000).

b Sequences listed are predicted to be helical by at least three criteria. Helical potential as predicted by: CF: Chou-Fasman predictions are based on frequency of different residues in helices, strands, and turns (Chou and Fasman 1974); GR: the GOR-IV algorithm is based on the frequency of residues at specific positions in the neighborhood of a helix or strand (Garnier et al. 1996). The number of + signs corresponds to robustness of prediction for CF and GR. HNN (Guermeur et al. 1999), PHD (Hofmann et al. 1999), and JPRED base predictions on consensus from multiple alignments and JPRED is also a consensus of several prediction algorithms (Cuff and Barton 1999). E: helix has significant hydrophobic moment at pH 7 (Eisenberg et al. 1984). SW: residues 177–181 are predicted to undergo secondary structure switching (Young et al. 1999).

c Helix stabilized at pH7 by presence of residues with opposite charges in successive turns of the helix.

d See Discussion.

The physical properties of extracellular proteins from free-living microorganisms have been studied not as completely as intracellular proteins in general and proteins from multicellular organisms, all of which function within a limited range of pH and temperatures. Therefore, similar data about α-agglutinin structure after perturbation of pH, temperature, disulfide bonds, and core interactions provide a useful comparison. We report here that α-agglutinin has an unusually broad range of conditions in which it is reversibly inactivated with concomitant reversible conformational switching from β-rich to a mixed α/β structure. To understand the basis of the conformational switching and determine the factors stabilizing the protein, we synthesized peptides of specific sequences found in α-agglutinin and studied their secondary structural characteristics. The results indicate that secondary structure prediction algorithms reflected the structure of α-agglutinin at neutral pH, rather than native pH. The basis for this difference is discussed.

Results

Effect of pH on conformation and binding activity of α-agglutinin20–351

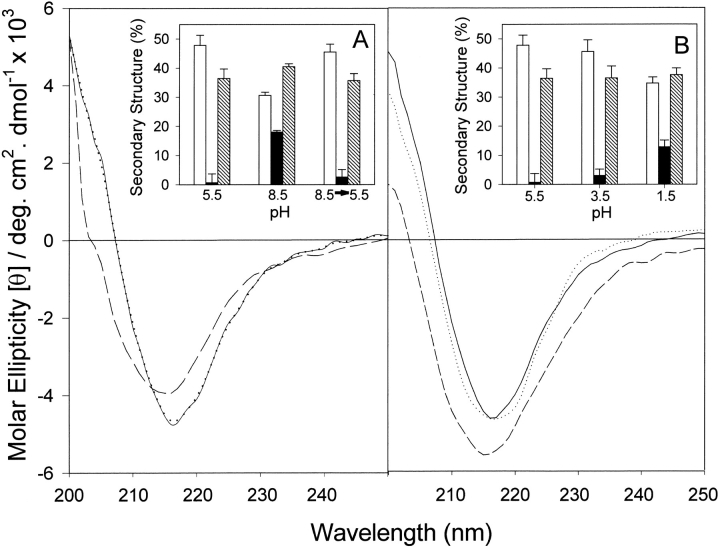

The circular dichroism (CD) spectrum of α-agglutinin20–351 at pH 5.5 was typical of β-sheet, with a positive band below 200 nm, a positive shoulder at 204 nm, and a negative maximum at 217 nm (Greenfield 1996). At pH 8.5, the spectra showed several differences characteristic of the presence of α-helix as well as β-sheet (Fig. 1A ▶).

Fig. 1.

Effect of pH on far-UV CD of α-agglutinin20–351. (A) Basic pH: Spectra were taken at 25°C in 30 mM sodium acetate at pH 5.5 (solid line), or in 100 mM sodium phosphate at pH 8.5 (dashed line). The spectrum of the reconstituted sample pH (8.5→5.5), which had been preincubated in 100 mM sodium phosphate at pH 8.5 for 2 h and 30 mM sodium acetate at pH 5.5 for 30 min, was measured at 25°C in 30 mM sodium acetate at pH 5.5 (dotted line). (Inset) Secondary structure content calculated by curve fitting: (open bar) β-sheet; (solid bar) α-helix; (hatched bar) aperiodic structures. Error bars: see text. All spectra contained ∼16% turn (not shown). (B) Acidic pH: Spectra were measured at 25°C in 30 mM sodium acetate at pH 5.5 (solid line); 30 mM sodium acetate at pH 3.5 (dotted line); or 100 mM sodium phosphate at pH 1.5 (dashed line). (Inset) Secondary structure content calculated by curve fitting.

We carried out secondary structure analyses and report results as mean and standard deviation of secondary structure content. The small standard deviations indicate both the concordance of structural analyses with spectra of model proteins, as well as the reproducibility of the spectral changes (see Materials and Methods). The results do not imply that the reported mean values are absolutely accurate in magnitude (Greenfield 1996). SELCON analyses (Sreerama and Woody 1993, Sreerama and Woody 1994) showed a decrease in β-sheet from 48% ± 2.5% at pH 5.5 to 30.6% ± 1.1% at pH 8.5, an increase in α-helix content from 0.7% ± 2.0% to 18% ± 0.6% and an increase in aperiodic structure from 36.4% ± 2.3% to 40.5% ± 1.0% (inset in Fig. 1A ▶).

There was a similar pH-dependent switch from β-sheet to α-helical structures seen by infrared spectroscopy (data not shown). Peptide mapping data was consistent with a pH-dependent change in structure, showing little proteolysis at pH 5.5, and substantial digestion at pH 7.8 (Chen et al. 1995).

With the change in its secondary structure, the binding activity of α-agglutinin20–351 decreased by ∼90% at pH 8.5. However, restoration of the pH from 8.5 to 5.5 followed by incubation at 25°C for 30 min restored the CD spectrum of α-agglutinin20–351 to its original shape with essentially complete recovery of the original β-sheet content (Fig. 1A ▶). In addition, at least 70% of the original binding activity was recovered.

In contrast to the effect of high pH, the CD spectrum of α-agglutinin20–351 at pH 3.5 still showed a typical β-sheet profile with slightly broadened bandwidth around the negative peak at 217 nm (Fig. 1B ▶), although the protein had no detectable activity. About 95% of binding activity was regained immediately after the protein was restored to pH 5.5. More pronounced changes were seen at pH 2.5 (not shown) and pH 1.5 (Fig. 1B ▶). The low pH spectrum was consistent with 13% helix and ∼35% β-sheet (insert in Fig. 1B ▶); 30% of its binding activity was regained after 2 h of incubation at pH 5.5 (not shown). Therefore, α-agglutinin20–351 was extremely stable at low pH, and the conformational changes were partially reversible even after exposure to pH 1.5.

Thermal stability of α-agglutinin20–351

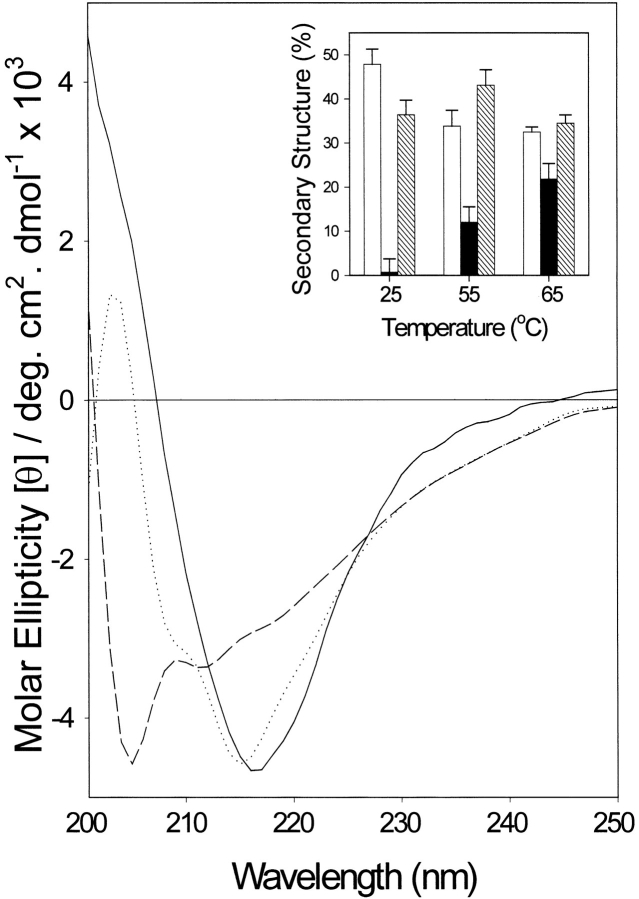

The binding activity of α-agglutinin is sensitive to both cold and heat (Terrance and Lipke 1981; Yamaguchi et al. 1982). α-Agglutinin20–351 was heated in 10°C steps from 25° to 75°C in a thermoregulated cuvette, and CD spectra were obtained after successive increases in temperature of 10°C. Each 10°C increase in temperature took 0.5 h, the protein being equilibrated at the new temperature for 20 min before acquisition of the spectra. The spectra showed little change at temperatures between 15° and 45°C. At 55°C the spectra were consistent with an increase of helical content to ∼13%, with a concomitant decrease in β-sheet content. There were further changes when the protein was denatured at 65°C (Fig. 2 ▶) and 75°C (data not shown). α-Agglutinin20–351 lost ∼90% of its binding activity at 55°C for 30 min, and half of the activity was regained upon a subsequent 2-h incubation at 25°C (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Effect of temperature on far-UV CD of α-agglutinin20–351. Samples were equilibrated at various temperatures for 20 min and spectra were measured in 30 mM sodium acetate at pH 5.5 at 15°, 25°, 35°, and 45°C (solid line); 55°C (dotted line); or 65°C (dashed line). (Inset) Secondary structure content at different temperatures calculated by curve fitting: (open bar) β-sheet; (solid bar) α-helix; (hatched bar) aperiodic structures. Error bars: see text. All spectra contained ∼16% turn (not shown).

These results were surprising, because of a previous use of a 5-min autoclaving step for the isolation of α-agglutinin (Yamaguchi et al. 1982). Therefore, CD spectra of α-agglutinin20–351 were taken at 25°C immediately after heating at 100°C for 5 min and after 2 h of incubation at 25°C after the 100°C step. The brief heating induced only a small change in the CD spectrum and secondary structure content of the protein. These changes were reversed by a subsequent 2-h incubation at 25°C (data not shown). The results imply that although α-agglutinin can be thermally denatured in 20- to 30-min incubations, it is not greatly changed by brief heating. Therefore, thermal unfolding must be a slow process.

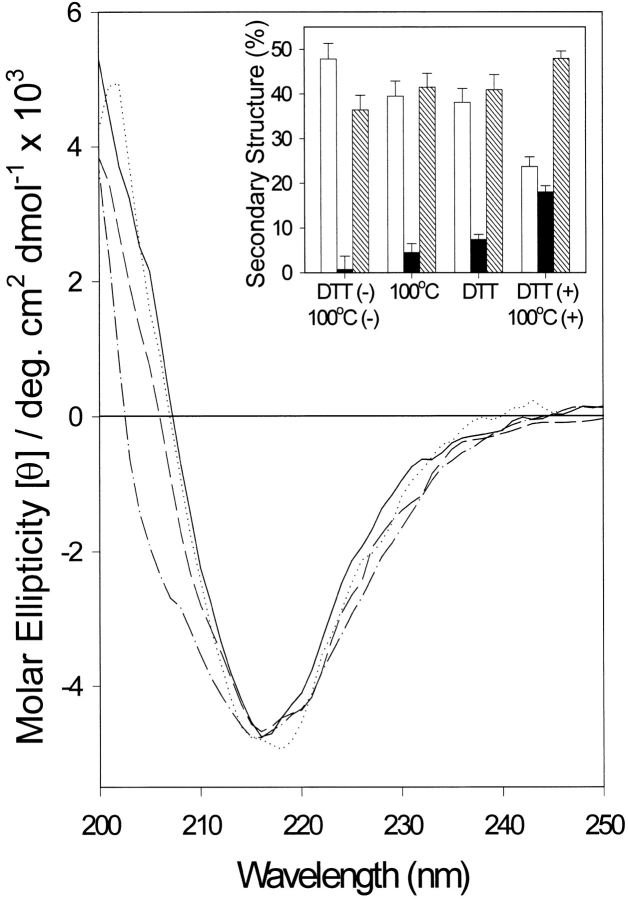

Role of disulfide bonds in conformation

α-Agglutinin20–351 contains disulfide bonds between Cys97–Cys114 in domain I and Cys202–Cys300 in domain III (Chen et al. 1995; Lipke et al. 1995; Grigorescu et al. 2000). To determine their roles in maintaining the structure of the protein, it was treated with 10 mM dithiothreitol in 100 mM sodium phosphate at pH 7.0 for 30 min at 37°C. The dithiothreitol (DTT)-treated sample was then reconstituted at pH 5.5 in fresh buffer without DTT at 25°C. DTT treatment inactivated α-agglutinin20–351 (Chen et al. 1995) and induced a small change in its CD spectrum, corresponding to a 5% increase in α-helix and a 10% decrease in β-strand (Fig. 3 ▶). However, when the DTT-treated sample was heated at 100°C for 5 min, there were substantial changes in its CD spectrum, consistent with loss of 60% of the β-sheet and an increase in helical and random structure content (Fig. 3 ▶). Therefore, the disulfides constrained some of the protein to a β-strand structure as well as stabilizing the native form against thermal denaturation.

Fig. 3.

Effect of DTT and brief heat treatment at 100°C on far-UV CD of α-agglutinin20–351. Spectra were taken at 25°C in 30 mM sodium acetate at pH 5.5; without any treatment (solid line); with 10 mM DTT treatment (dotted line); with heat treatment at 100°C for 5 min (dashed line); or DTT treatment plus heat treatment at 100°C for 5 min (dash/dot line). (Inset) Secondary structure content calculated by curve fitting: (open bar) β-sheet;; (solid bar) α-helix; (hatched bar) aperiodic structures. Error bars: see text. All spectra contained ∼16% turn (not shown).

Effect of pH on conformation of small peptide derivatives of α-agglutinin

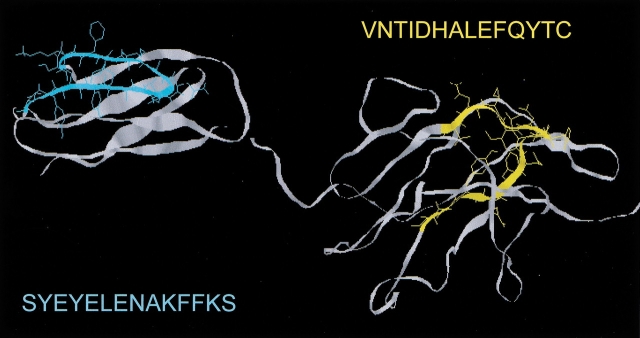

A consensus of secondary structure prediction algorithms strongly characterizes a substantial portion of α-agglutinin as helical (Table 1). To investigate the idea that structural switching from β-sheet to α-helix may have occurred in specific regions in the protein, we synthesized two of the peptides predicted to have high helical potential. In the modeled structures, these regions have β-loop-β structures (Fig. 4 ▶) (Grigorescu et al. 2000). Secondary structures of these model peptides were stabilized with trifluoroethanol (TFE), which stabilizes helices in peptides with propensity to form such structures (Lau et al. 1984; Sonnichsen et al. 1992; Hamada et al. 1995; Shiraki et al. 1995; Najbar et al. 1997) and also stabilizes β-sheets in peptides with appropriate sequences (Lu et al. 1984; Martenson et al. 1985; Yang et al. 1994; Wang et al. 1995; Najbar et al. 1997).

Fig. 4.

Three-dimensional orientation of two peptides of high helical propensity derived from the proposed β-strands regions of α-agglutinin20–351. Model of domains II and III of α-agglutinin, with peptide I (C–C` strand region of domain II) shown in cyan and peptide II (E–F strand region of domain III) shown in yellow. The models were based on similarity to the CD2/CD4 subfamily of the Ig superfamily, and were tested by peptide mapping and site-directed mutagenesis (Lipke et al. 1995; Grigorescu et al. 2000). The peptide sequences are shown in single letter code, and their helical propensities are summarized in Table 1.

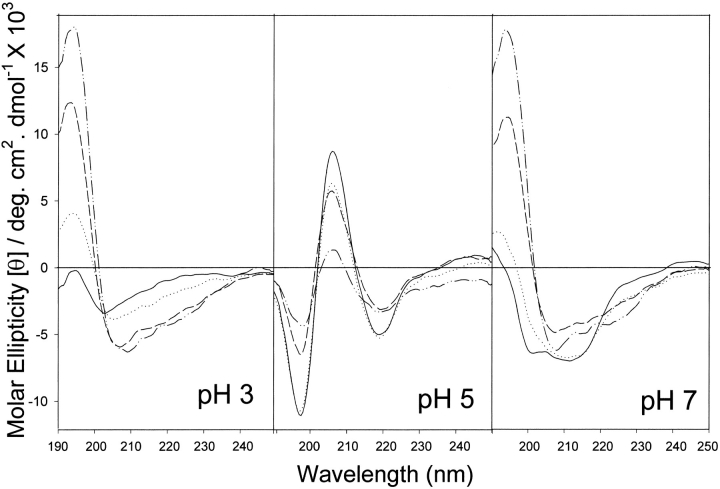

The far-UV CD spectrum of peptide I, derived from domain II of α-agglutinin, displayed remarkable pH and TFE dependence (Fig. 5 ▶). At pH values <3, the spectra were similar to one another, and were similar to those at pH >8 (not shown). In the absence of TFE, the spectrum at these pH values was typical of random coil with a negative peak a little above 200 nm (Yang et al. 1986; Woody 1995). At each pH, addition of TFE changed the spectrum toward α-helix with characteristic negative ellipticity near 208 and 222 nm (Yang et al. 1986), with a smooth two-state transition with an isodichroic point at 203 nm.

Fig. 5.

Effect of TFE on far-UV CD of peptide I at different pH values. Spectra were measured in 10 mM sodium phosphate at pH 2–10 in 10% TFE (solid line); 20% TFE (dotted line); 40% TFE (dashed line), or 60% TFE (dash/dot line). The spectra below pH 3 were similar to one another, as were those above 8. The spectra at pH 3, 5, and 7 are shown.

At pH 5, TFE addition also produced a two-state transition, as indicated by isodichroic points at 202, 212, and 227 nm. At low TFE concentrations the spectra had β-like characteristics, especially the negative peak near 217 nm (Fig. 5 ▶, center). With more TFE, this band shifted slightly to longer wavelength, and at high TFE, the ellipticity became somewhat more intensely negative near 210 nm, showing a negative shoulder at about 212 nm. The α-helix has its characteristic bands at 208–210 nm and 222 nm. The TFE induced shift was thus in the helical direction.

The pair of oppositely signed bands at ∼197 and 206 nm is probably an effect of the interaction tyrosine side chains (Kahn 1979; Woody and Dunker 1996). Overlap of the strong positive band at 206 nm with the negatively signed helix band that is normally near 208 nm both reduces the apparent intensity of the helix band and shifts its apparent position to longer wavelength, thus producing the 212-nm shoulder in high TFE instead of a band at 208 nm.

In the β-conformation shown in the model in Figure 4 ▶, the two tyrosines are on the same side of the sheet and are close enough for strong coupling between their transitions. The pair of bands at low TFE, in fact, looks like an exciton couple (Kahn 1979; Woody and Dunker 1996). As the number of molecules in the β-conformation decreases, this coupling is lost irrespective of whether the molecules become helical or unordered, for in the helical form they will point away from one another, reducing their spectroscopic interaction. Thus, the data for peptide I describe a shift from a population of molecules many of which are relatively ordered in a way that allows strong aromatic side chain coupling toward forms that do not. These results, including the negative band at 217 nm, are consistent with the idea that the partially ordered structure at low TFE is β-sheet, whereas the population at high TFE contains both disordered molecules and molecules that are partly helical (Yang et al. 1994; Wang et al. 1995).

Similar trends toward helical structure were seen in the spectra at pH 7 (Fig. 5 ▶, right), but the absence of a clear isodichroic point indicates that more than two conformational forms are involved.

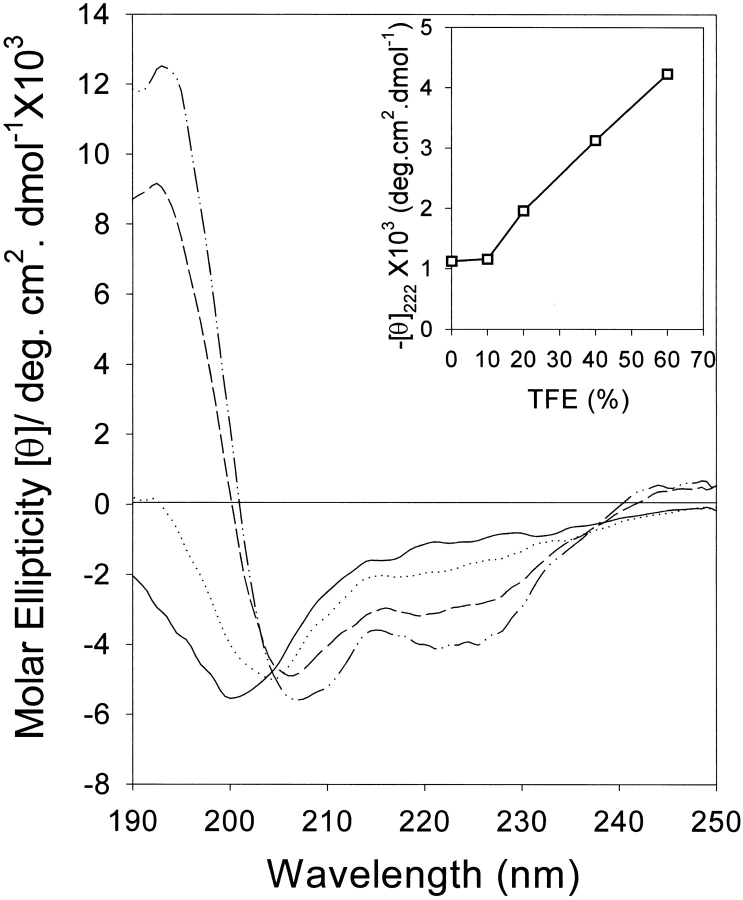

Unlike peptide I, peptide II, derived from domain III of the protein, had similar CD spectra at pH values between 2 and 10; therefore, only the results at pH 5 are shown in Figure 6 ▶. Increasing TFE concentrations produced isodichroic points at 215 and 238 nm. These results are indicative of a two-state transition between coil and α-helix (Yang et al. 1986; Woody 1995).

Fig. 6.

Effect of TFE on far-UV CD of peptide II. Spectra were measured in 10 mM sodium phosphate at pH 2–10 in 0% TFE (dash/dot line); 10% TFE (solid line); 20% TFE (dotted line); 40% TFE (dashed line), or 60% TFE (dash/dot/dot line). Because the spectra at all pH values were similar, only the curves at pH 5 are shown. (Inset) Molar ellipticity at 222 mn versus concentration of TFE.

Discussion

Reversible conformational switching of α-agglutinin

Although secondary structure prediction algorithms strongly designated α-agglutinin20–351 as a mixed α/β structure, CD spectroscopy, peptide mapping, and homology modeling show that it is all-β. This apparent inconsistency can be resolved by the realization that the protein has a highly flexible structure that is constrained to β-rich conformation under native conditions. Helical regions appear when environmental conditions are altered; therefore, both β-rich and α/β states exist.

Table 1 lists the nine sequences in α-agglutinin20–351 that are predicted to be helical by three or more independent criteria. These residues represent 17% of the total, about the same as the maximal helical content observed in vitro. This fraction is high relative to other members of the Ig superfamily (range 2–12%) and much higher than the Als proteins from Candida albicans, which show 6% predicted helical sequences. In α-agglutinin, two-thirds of these predicted helical sequences occur in loop regions of the three-dimensional models, and therefore, represent regions of potential flexibility in the structure.

Model peptides from two of these regions showed high helical propensity, forming that structure in the presence of TFE, which stabilizes secondary structures by favoring intrapeptide interactions at the expense of solvent interactions. Therefore, these peptides show the expected low-energy transitions to helical conformation. In addition peptide I, which has a predicted native conformation of strand-loop-strand, shows a marked pH-dependent transition between unstructured, β-sheet, and α-helical forms (Fig. 5 ▶). The transitions depend on solvation effects and charge. To our knowledge, such a dual transition has not been previously reported in an isolated peptide derived from a protein sequence, although similar behavior was seen in designed model peptides (Yang et al. 1994; Wang et al. 1995; Zhang and Rich 1997). The bases for these interactions are the interplay of local and nonlocal interactions.

Role of charge interactions

The pH dependence of the conformational shift of peptide I illustrates the importance of charge interactions. In both peptide I and the model of the native protein, the side chains of Glu residues at protein positions 144, 146, and 148 would protrude to the same (exterior) side of a β-strand (Grigorescu et al. 2000). These residues alternate with residues expected to pack into the hydrophobic core of the domain (Fig. 4 ▶). At pH 5.5, partial neutralization of these Glu residues would reduce repulsive interactions among them. On the other hand, full ionization at pH >7 would destabilize the strand. Moreover, ionization of Glu-148 might stabilize α-helix formation, because it could form a salt bridge with Lys-151 in the next turn of a potential helix. It should also be noted that the negatively charged amino acids occur toward the amino end of the peptide, whereas the two lysines occur toward the carboxyl end. They are thus positioned to stabilize a helix dipole.

These peptides and other regions of high α-helical potential must be constrained within the native protein to conform to a β-rich state. Charge distributions that would stabilize β-strands at pH 5.5 but would promote α-helices at neutral or highly acidic pH occur in the vicinity of Asp-63, Glu-93, Asp-266, Asp-271, and Glu-295. In these regions there are multiple acidic residues and partial ionization would promote strand-like or extended structures. In contrast, full protonation at low pH would eliminate charge repulsion, and, as with polyglutamic acid and peptide I, would allow the helical propensities to emerge (Fig. 1B ▶) (Narhi et al. 1996). Complete ionization, in contrast, would lead to repulsion between anionic residues and stabilization of helices by appropriately positioned cationic residues. Thus, several regions of the protein have properties that favor helical structure at pH <2 or >7, but strand-like conformation at pH 5.5. Among these sequences peptide II is helical in TFE solutions but corresponds to a region of β-loop-β structure in the molecules in the Ig superfamily (Williams and Barclay 1988; Williams et al. 1989; Chen et al. 1995; Lipke et al. 1995).

Role of physical constraint

In α-agglutinin, there are two examples of stabilization of the β-rich structure by the peptide backbone. Protease Arg-C cleavage of the protein between Lys-154 and Ser-155 in the region of peptide I slightly increases helical content (Chen et al. 1995). Similarly, the disulfides must constrain part of the protein to all β-conformation, because reduction leads to a decrease in β-strand content and an increase of helical content to ∼5%, the equivalent of ∼15 residues (Fig. 3 ▶). This constraint is in addition to the conventional function of disulfides in stabilizing the hydrophobic core of the Ig domains, including α-agglutinin (Fig. 3 ▶). These results show that the physical constraints of covalent bonds and domain structure contribute to the β-rich state of α-agglutinin. A similar mechanism of local forcing of conformational switching has been observed in HCDR3 of a hybrid immunoglobulin (Fan et al. 1999).

A basis for low pH stability

Some aspects of the stability of α-agglutinin were different from other members of Ig superfamily. For example: α-agglutinin was labile to high pH and unusually stable to acid (Fig. 1 ▶). Such stabilization at low pH might be induced by strengthened interstrand hydrogen bonds (Worobec et al. 1988; Yang et al. 1994; Molinari et al. 1996). The conformational stability at pH 3.5 (Fig. 1 ▶) implies that the pH 4.0 threshold for agglutination activity was as a result of protonation of one or more amino acid residues critical for binding, an interpretation consistent with the rapid recovery of activity upon resuspension at pH 5.5. The acid stability of α-agglutinin may relate to its acidic nature: α-agglutinin20–351 has a theoretical isoelectric point at pH 3.98, making it anionic at pH 5.5. In contrast, other members of the Ig superfamily have basic isoelectric points and are cationic (4–12 net positive charges) near the physiological pH. The pI of α-agglutinin reflects a paucity of basic residues in the sequence, rather than an abundance of acidic residues relative to other members of the Ig superfamily (not shown). The deficiency in cationic groups would cause more severe charge repulsion of anions at neutral pH and less instability from repulsion of cations at low pH.

Importance of conformational switching

Conformational changes in proteins play important biological roles. For instance, dramatic transition from nonhelical to helical structures in viral fusion proteins are essential in promoting fusion of the virus and the target cell membranes (Worobec et al. 1988; Carr and Kim 1993; Bullough et al. 1994; Yang et al. 1994; Molinari et al. 1996; Chan et al. 1997; Weissenhorn et al. 1997). Helix to β-strand switching in the amyloid and prion proteins appears to be involved in diseases such as scrapie, bovine spongiform encephalitis, and, possibly Creutzfeld-Jacob and Alzheimer's (Baskakov et al. 2000).

In the intact proteins these switches are irreversible under biological conditions, although a large peptide from the prion protein undergoes a reversible transition (Prusiner 1991; Jackson et al. 1999; Baskakov et al. 2000). The protein sequences involved have strong propensities for the secondary structures adopted after conversion, propensities that are overridden by tertiary interactions in the preconversion forms. When environmental conditions weaken long-range effects, local interactions come to the fore and drive the conformational transitions. α-Agglutinin is similar in that high pH relaxes long-range constraints, allowing the underlying local propensity, in this case for α-helix, to manifest itself. Where α-agglutinin differs from these is that the changes in structure are reversible under biologically relevant conditions.

The α-agglutinin sequences are different from "switch sequences" such as Minor and Kim's "chameleon" sequence and peptides in the dimeric yeast repressor protein Matα2p (Minor and Kim 1996; Tan and Richmond 1998). The chameleon sequence is an 11-residue peptide that is α-helical when it is in one region of its protein and in a strand-turn-strand conformation when it is in another area. In Matα2p, an eight-residue sequence in the DNA-binding region forms a β-strand in one monomer and an α-helix in the other monomer. In these cases, the local secondary structure propensities are ambiguous, and neither α-helical nor β-sheet conformation is strongly predicted (data not shown), and long-range interactions of the tertiary context determine the conformation. There are four predicted switch regions in α-agglutinin20–351 comprising <7% of the sequence (Young et al. 1999). Only one of these sequences (177 –181) is within predicted helical regions in Table 1. Thus, the majority of potential switching regions in α-agglutinin are β-rich in the native protein despite strongly helical propensities, rather than having ambivalent potential.

These potentially helical regions of α-agglutinin are not manifested in the native protein, but appear under perturbing conditions. In the intact protein, an α/β state was thermodynamically accessible upon small changes in conditions, and indeed pH titration and thermal denaturation spectra showed isodichroic points characteristic of equilibria between two conformational states (Figs. 1 and 2 ▶ ▶, and data not shown). Similar transitions occur during folding or unfolding in β-lactoglobulin and other proteins at acidic pH values not normally encountered by the proteins (Shiraki et al. 1995; Forge et al. 2000). The switching in α-agglutinin is seen under common environmental conditions and may be correlated with the ability to survive a variety of environments while retaining the flexibility to allow conformational changes on ligand binding (Zhao et al. 2001). Therefore, α-agglutinin may have the properties that a helix-containing form can constitute a non-native "metastable" state that can easily rearrange to the native all-β structure upon reconstitution to native environmental conditions.

Materials and methods

Overexpression and purification of α-agglutinin20–351

Yeast strain Lα21 (MATα ade2–1 his3–11,15 leu2–3,112 trp1–1 ura3–2 can1–100 agα1–3) containing pPGK-Agα1351 constitutively expresses and secretes α-agglutinin20–351, which is fully active (Wojciechowicz et al. 1993; Chen et al. 1995). Cell culture supernatant (4 L) was concentrated to 50 mL through a millipore filtration apparatus with a membrane having a 30-kD molecular mass cutoff. Concentrated supernatant was dialyzed against 4 L of 30 mM sodium acetate buffer at pH 5.5 at 4°C overnight and then chromatographed on DEAE–Sephadex A25 at 25°C. Partially purified α-agglutinin20–351 was eluted with 350 mM sodium chloride in 30 mM sodium acetate at pH 5.5. The sample was dialyzed at 4°C against 30 mM sodium acetate at pH 5.5, lyophilized, resuspended in 30mM sodium acetate at pH 5.5, 0.01% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and partially deglycosylated by endoglycosidase H. The deglycosylated protein was further purified at 25°C by a Bio-Gel P-60 size exclusion column equilibrated in 30 mM sodium acetate at pH 5.5 (Chen et al. 1995). α-Agglutinin20–351 had an apparent molecular mass of 45 kD on Coomassie Blue-stained SDS gels and was of 99% purity by scanning densitometry (Molecular Dynamics). Each preparation produced 0.2–0.4 mg of α-agglutinin20–351.

Agglutination assay

S. cerevisiae wild-type haploid strains X2180–1A (MATa SUC2 mal mel gal2 CUP1) and X2180–1B (MATα SUC2 mal mel gal2 CUP1), obtained from the Yeast Genetics Stock Center (Berkeley, CA), were used for bioassays. a cells and α cells were grown separately in minimal medium to 2 × 107 cells per mL, and a cells were treated with the sex pheromone α-factor as described (Terrance and Lipke 1981). These cells were harvested and washed in 100 mM sodium acetate at pH 5.5 at 25°C. α-Agglutinin was incubated with a cells on a rotary shaker at 25°C for 90 min, and α cells were then added. The activity of α-agglutinin was determined by its ability to inhibit the agglutinability of a cells (Terrance and Lipke 1981), with one unit being the amount of protein needed to inhibit agglutination by 10%.

pH treatment of α-agglutinin20–351

Purified α-agglutinin20–351 (0.2 mg/mL) was dialyzed against 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 1.5, 2.5, 7.5, and 8.5; 30 mM sodium acetate at pH 3.5 and 5.5; or 100 mM 3-(cyclohexylamino)-1-propanesulfonic acid (CAPS) at pH 9.5 and 10.5 at 4°C overnight. α-Agglutinin20–351 in buffers with different pH was reconstituted to pH 5.5 by dialyzing against 30 mM sodium acetate at pH 5.5.

Reduction of disulfide bonds of α-agglutinin20–351

α-Agglutinin20–351 (0.2 mg/mL) was treated with 10 mM DTT in 100 mM sodium phosphate at pH 7.0 at 37°C for 30 min. The DTT-containing buffer was then washed away by centrifugation through Microcon filters as above. α-Agglutinin20–351 retained on the membrane was suspended in 30 mM sodium acetate at pH 5.5 for CD and agglutination assay.

Synthesis and purification of peptides

Peptides were synthesized by the solid phase method using fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl chemistry on an Applied Biosystems automated model 432A peptide synthesizer. The peptide resins were treated with 80% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)/5% water/5% ethanedithiol/10% thioanisole at room temperature for 2 h. The cleaved and deprotected peptides were then precipitated and washed in cold methyl t-butyl ether and collected by centrifugation at 25°C.

Purification of the peptides was achieved by reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) on a C-18 column (21.4 × 250 mm) using 0.1% TFA as buffer A and 70% acetonitrile in 0.1% TFA as buffer B. A linear gradient between 0% and 100% buffer B in buffer A was used at a flow rate of 5 mL/min over a period of 60 min. The elution profile was monitored at 215 nm. The purified peptides were lyophilized and redissolved in deionized water before dilution into appropriate buffer.

CD spectroscopy

Far UV CD spectra were recorded on a Jasco J-710 spectropolarimeter in quartz, thermoregulated cuvettes (HELLMA) with 0.1-cm and 0.05-cm path lengths. Each spectrum represents the average of 10 scans taken at 0.5 nm intervals from 250 to 200 nm for the protein and 250–190 nm for the peptides. The spectra were corrected by subtraction of the appropriate buffer baseline spectra and smoothed by the Jasco Series 700 software. Each experiment was repeated three times. For conversion to molar ellipticity from the observed ellipticity for α-agglutinin20–351, a mean residue weight of 111.77 was used. The concentrations of protein and peptides were obtained from UV absorption at 280 nm by using extinction coefficients of 51,850 for the protein, and 2560 and 1280 for peptides I and II, respectively. The coefficients were calculated from the amino acid compositions of the protein and peptides as being more accurate than methods based on quantitation of small amounts of protein (Gill and Hippel 1989).

CD data were analyzed by the self-consistent method with the SELCON program (Gill and Hippel 1989; Woody 1995; Woody and Dunker 1996), which uses a database of 33 reference proteins as standards. This program provides accurate estimates of conformation from CD, and is not especially dependent on data from wavelengths lower than 200 nm (Greenfield 1996). The error bars shown in Figures 1–3 ▶ ▶ ▶ are the standard deviations of the mean estimates for each secondary structure element for all data sets in the final iteration. Changes in secondary structure content were similar when the data were analyzed by SELCON or by the convex constraint method (Chen et al. 1995).

We averaged the secondary structure estimates for six independent CD experiments carried out over the course of the year, using two different preparations of α-agglutinin20–351. The CD spectra were obtained in 30 mM sodium acetate buffer at pH 5.5 at 25°C. The mean and standard deviations of the secondary structure contents were: α-helix, 2.2% ± 1.3%; β-sheet, 45.0% ± 1.3%; turn 16.1% ± 3.3%; and other structures, 37.3% ± 2.9%. When turn and other structures were summed before averaging, the value was 53.4% ± 1.3%. These values for standard deviations imply standard errors of the mean of 0.6% or less, and 95% confidence limits of ±1.3% or less.

Infrared spectroscopy

α-Agglutinin20–351 was dissolved in D2O-based 10 mM sodium cacodylate buffer containing 10 mM mannitol and 0.1 M NaCl at pD values of 6.0 and 9.0, corresponding to pH values of 5.6 and 8.6. Spectra were acquired using a Bruker Optics Vector22 FT-IR spectrometer (Billerica, MA). The pathlength was 50 μm between CaF2 windows. Five hundred interferograms were collected and Fourier transformed to obtain the absorption spectra, and resolution was enhanced by comparing second derivatives. The spectra were analyzed for presence of peaks characteristic of antiparallel β-sheet at 1682 cm−1 and 1639 cm−1 and for the α-helix peak at 1647 cm−1.

Acknowledgments

We are most grateful to Dr. Peter Lasch and Dr. Max Diem for the infrared spectroscopy. We also thank Dr. Dixie Goss for use of CD spectrometer and Dr. Y. K. Yip for peptide synthesis. This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Science (1R01-GM47176) to Janet Kurjan, University of Vermont; the Research Center in Minority Institutions Program of National Institutes of Health (RR-03037); and New Jersey Agriculture Experiment Station (Paper D-01405-2-99).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges.This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Abbreviations

Ig, immunoglobulin

CD, circular dichroism

CAPS, 3-(cyclohexylamino)-1-propanesulfonic acid

DTT, dithiothreitol

SDS, sodium dodecyl sulfate

EDTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

TFA, trifluoroacetic acid

HPLC, high performance liquid chromatography

TFE, trifluoroethanol

Article and publication are at www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.41701.

References

- Baldwin, E.P., Hajiseyedjavadi, O., Baase, W.A., and Matthews, B.W. 1993. The role of backbone flexibility in the accommodation of variants that repack the core of T4 lysozyme. Science 262 1715–1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskakov, I.V., Aagaard, C., Mehlhorn, I., Wille, H., Groth, D., Baldwin, M.A., Prusiner, S.B., and Cohen, F.E. 2000. Self-assembly of recombinant prion protein of 106 residues. Biochemistry 39 2792–2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullough, P.A., Hughson, F.M., Skehel, J.J., and Wiley, D.C. 1994. Structure of influenza haemagglutinin at the pH of membrane fusion. Nature 371 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappellaro, C., Hauser, K., Mrsa, V., Watzele, M., Watzele, G., Gruber, C., and Tanner, W. 1991. Saccharomyces cerevisiae a- and alpha-agglutinin: Characterization of their molecular interaction. EMBO J. 10 4081–4088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr, C.M. and Kim, P.S. 1993. A spring-loaded mechanism for the conformational change of influenza hemagglutinin. Cell 73 823–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, D.C., Fass, D., Berger, J.M., and Kim, P.S. 1997. Core structure of gp41 from the HIV envelope glycoprotein. Cell 89 263–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.H., Shen, Z.M., Bobin, S., Kahn, P.C., and Lipke, P.N. 1995. Structure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae alpha-agglutinin. Evidence for a yeast cell wall protein with multiple immunoglobulin-like domains with atypical disulfides. J. Biol. Chem. 270 26168–26177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou, P.Y. and Fasman, G.D. 1974. Prediction of protein conformation. Biochemistry 13 222–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuff, J.A. and Barton, G.J. 1999. Evaluation and improvement of multiple sequence methods for protein secondary structure prediction. Proteins 34 508–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Nobel, H., Lipke, P.N., and Kurjan, J. 1996. Identification of a ligand-binding site in an immunoglobulin fold domain of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae adhesion protein alpha-agglutinin. Mol. Biol. Cell 7 143–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, D., Weiss, R.M., and Terwilliger, T.C. 1984. The hydrophobic moment detects periodicity in protein hydrophobicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 81 140–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Z.C., Shan, L., Goldsteen, B.Z., Guddat, L.W., Thakur, A., Landolfi, N.F., Co, M.S., Vasquez, M., Queen, C., Ramsland, P.A., and Edmundson, A.B. 1999. Comparison of the three-dimensional structures of a humanized and a chimeric Fab of an anti-gamma-interferon antibody. J. Mol. Recognit. 12 19–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forge, V., Hoshino, M., Kuwata, K., Arai, M., Kuwajima, K., Batt, C.A., and Goto, Y. 2000. Is folding of beta-lactoglobulin non-hierarchic? Intermediate with native-like beta-sheet and non-native alpha-helix. J. Mol. Biol. 296 1039–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnier, J., Gibrat, J.F., and Robson, B. 1996. GOR method for predicting protein secondary structure from amino acid sequence. Methods Enzymol. 266 540–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill, S.C. and Hippel, P.H.v. 1989. calculation of protein extinction coefficients from amino acid sequence data. Anal. Biochem. 182 319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, N.J. 1996. Methods to estimate the conformation of proteins and polypeptides from circular dichroism data. Anal. Biochem. 235 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigorescu, A., Chen, M.-H., Zhao, H., Kahn, P.C., and Lipke, P.N. 2000. A CD2-based model of yeast alpha-agglutinin elucidates solution properties and binding characteristics. IUBMB Life 50 105–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guermeur, Y., Geourjon, C., Gallinari, P., and Deleage, G. 1999. Improved performance in protein secondary structure prediction by inhomogeneous score combination. Bioinformatics 15 413–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada, D., Kuroda, Y., Tanaka, T., and Goto, Y. 1995. High helical propensity of the peptide fragments derived from beta-lactoglobulin, a predominantly beta-sheet protein. J. Mol. Biol. 254 737–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, K. and Tanner, W. 1989. Purification of the inducible alpha-agglutinin of S. cerevisiae and molecular cloning of the gene. FEBS Lett. 255 290–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, K., Bucher, P., Falquet, L., and Bairoch, A. 1999. The PROSITE database, its status in 1999. Nucleic Acids Res. 27 215–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, G.S., Hosszu, L.L., Power, A., Hill, A.F., Kenney, J., Saibil, H., Craven, C.J., Waltho, J.P., Clarke, A.R., and Collinge, J. 1999. Reversible conversion of monomeric human prion protein between native and fibrilogenic conformations. Science 283 1935–1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, P.C. 1979. The interpretation of near-ultraviolet circular dichroism. Methods Enzymol. 61 339–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapteyn, J.C., Montijn, R.C., Vink, E., de la Cruz, J., Llobell, A., Douwes, J.E., Shimoi, H., Lipke, P.N., and Klis, F.M. 1996. Retention of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell wall proteins through a phosphodiester-linked beta-1,3-/beta-1,6-glucan heteropolymer. Glycobiology 6 337–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau, S.Y., Taneja, A.K., and Hodges, R.S. 1984. Synthesis of a model protein of defined secondary and quaternary structure. Effect of chain length on the stabilization and formation of two-stranded alpha-helical coiled-coils. J. Biol. Chem. 259 13253–13261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipke, P.N. and Kurjan, J. 1992. Sexual agglutination in budding yeasts: Structure, function, and regulation of adhesion glycoproteins. Microbiol. Rev. 56 180–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipke, P.N., Terrance, K., and Wu, Y.S. 1987. Interaction of alpha-agglutinin with Saccharomyces cerevisiae a cells. J. Bacteriol. 169 483–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipke, P.N., Chen, M.H., de Nobel, H., Kurjan, J., and Kahn, P.C. 1995. Homology modeling of an immunoglobulin-like domain in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae adhesion protein alpha-agglutinin. Protein Sci. 4 2168–2178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.F., Kurjan, J., and Lipke, P.N. 1994. A pathway for cell wall anchorage of Saccharomyces cerevisiae alpha-agglutinin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14 4825–4833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.F., Montijn, R.C., Brown, J.L., Klis, F., Kurjan, J., Bussey, H., and Lipke, P.N. 1995. Glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-dependent cross-linking of alpha-agglutinin and beta 1,6-glucan in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell wall. J. Cell. Biol. 128 333–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z.X., Fok, K.F., Erickson, B.W., and Hugli, T.E. 1984. Conformational analysis of COOH-terminal segments of human C3a. Evidence of ordered conformation in an active 21-residue peptide. J. Biol. Chem. 259 7367–7370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martenson, R.E., Park, J.Y., and Stone, A.L. 1985. Low-ultraviolet circular dichroism spectroscopy of sequential peptides 1-63, 64-95, 96-128, and 129-168 derived from myelin basic protein of rabbit. Biochemistry 24 7689–7695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minor, D.L. Jr. and Kim, P.S. 1996. Context-dependent secondary structure formation of a designed protein sequence. Nature 380 730–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molinari, H., Ragona, L., Varani, L., Musco, G., Consonni, R., Zetta, L., and Monaco, H.L. 1996. Partially folded structure of monomeric bovine beta-lactoglobulin. FEBS Lett. 381 237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najbar, L.V., Craik, D.J., Wade, J.D., Salvatore, D., and McLeish, M.J. 1997. Conformational analysis of LYS(11-36), a peptide derived from the beta-sheet region of T4 lysozyme, in TFE and SDS. Biochemistry 36 11525–11533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narhi, L.O., Philo, J.S., Li, T., Zhang, M., Samal, B., and Arakawa, T. 1996. Induction of alpha-helix in the beta-sheet protein tumor necrosis factor-alpha: acid-induced denaturation. Biochemistry 35 11454–11460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusiner, S.B. 1991. Molecular biology of prion diseases. Science 252 1515–1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiraki, K., Nishikawa, K., and Goto, Y. 1995. Trifluoroethanol-induced stabilization of the alpha-helical structure of beta-lactoglobulin: Implication for non-hierarchical protein folding. J. Mol. Biol. 245 180–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnichsen, F.D., Van Eyk, J.E., Hodges, R.S., and Sykes, B.D. 1992. Effect of trifluoroethanol on protein secondary structure: An NMR and CD study using a synthetic actin peptide. Biochemistry 31 8790–8798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreerama, N. and Woody, R.W. 1993. A self-consistent method for the analysis of protein secondary structure from circular dichroism. Anal. Biochem. 209 32–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1994. Protein secondary structure from circular dichroism spectroscopy. Combining variable selection principle and cluster analysis with neural network, ridge regression and self-consistent methods. J. Mol. Biol. 242 497–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, S. and Richmond, T.J. 1998. Crystal structure of the yeast MATalpha2/MCM1/DNA ternary complex. Nature 391 660–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrance, K. and Lipke, P.N. 1981. Sexual agglutination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 148 889–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J., Hodges, R.S., and Sykes, B.D. 1995. Effect of trifluoroethanol on the solution structure and flexibility of desmopressin: A two-dimensional NMR study [published erratum appears in Int J Pept Protein Res 1995 Dec;46(6):547]. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 45 471–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissenhorn, W., Dessen, A., Harrison, S.C., Skehel, J.J., and Wiley, D.C. 1997. Atomic structure of the ectodomain from HIV-1 gp41. Nature 387 426–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A.F. and Barclay, A.N. 1988. The immunoglobulin superfamily—domains for cell surface recognition. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 6 381–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A.F., Davis, S.J., He, Q., and Barclay, A.N. 1989. Structural diversity in domains of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 54 637–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojciechowicz, D. 1990. "The immunological and molecular characterization of alpha-agglutinin from Saccharomyces cerevisiae." Dissertation, City University of New York, New York, NY.

- Wojciechowicz, D., Lu, C.F., Kurjan, J., and Lipke, P.N. 1993. Cell surface anchorage and ligand-binding domains of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell adhesion protein alpha-agglutinin, a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13 2554–2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody, R.W. 1995. Circular dichroism. Methods Enzymol. 246 34–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody, R.W. and Dunker, K. 1996. Aromatic and cystine sidechain circular dichroism in proteins. In Circular dichroism and the conformational analysis of macromolecules (ed G.D. Fasman), pp. 109–157. Plenum Press, New York, NY

- Worobec, E.A., Martin, N.L., McCubbin, W.D., Kay, C.M., Brayer, G.D., and Hancock, R.E. 1988. Large-scale purification and biochemical characterization of crystallization-grade porin protein P from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 939 366–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, M., Yoshida, K., and Yanagishima, N. 1982. Isolation and partial characterization of cytoplasmic alpha agglutination substance in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 139 125–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.J., Pikeathly, M., and Radford, S.E. 1994. Far-UV circular dichroism reveals a conformational switch in a peptide fragment from the beta-sheet of hen lysozyme. Biochemistry 33 7345–7353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.T., Wu, C.S., and Martinez, H.M. 1986. Calculation of protein conformation from circular dichroism. Methods Enzymol. 130 208–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young, M., Kirshenbaum, K., Dill, K.A., and Highsmith, S. 1999. Predicting conformational switches in proteins. Protein Sci. 8 1752–1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S. and Rich, A. 1997. Direct conversion of an oligopeptide from a beta-sheet to an alpha-helix: A model for amyloid formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 94 23–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H. 1999. "Biochemical characterization of yeast cell adhesion proteins." Dissertation, City University of New York, New York, NY.

- Zhao, M., Shen, Z.-M., Kahn, P.C., and Lipke, P.N. 2001. Interaction of alpha-agglutinin and a-agglutinin, Saccharomyces cerevisiae sexual cell adhesion molecules. J. Bacteriol. 183 2874–2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]