Abstract

Photoionization of an atom by X-rays usually removes an inner shell electron from the atom, leaving behind a perturbed "hollow ion" whose relaxation may take different routes. In light elements, emission of an Auger electron is common. However, the energy and the total number of electrons released from the atom may be modulated by shake-up and shake-off effects. When the inner shell electron leaves, the outer shell electrons may find themselves in a state that is not an eigen-state of the atom in its surroundings. The resulting collective excitation is called shake-up. If this process also involves the release of low energy electrons from the outer shell, then the process is called shake-off. It is not clear how significant shake-up and shake-off contributions are to the overall ionization of biological materials like proteins. In particular, the interaction between the outgoing electron and the remaining system depends on the chemical environment of the atom, which can be studied by quantum chemical methods. Here we present calculations on model compounds to represent the most common chemical environments in proteins. The results show that the shake-up and shake-off processes affect ∼20% of all emissions from nitrogen, 30% from carbon, 40% from oxygen, and 23% from sulfur. Triple and higher ionizations are rare for carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen, but are frequent for sulfur. The findings are relevant to the design of biological experiments at emerging X-ray free-electron lasers.

Keywords: X-rays, photoionization, shake-up, shake-off, Auger emission, radiation damage, peptides, proteins

Computer simulations (Neutze et al. 2000) show that ultrashort and high-intensity X-ray pulses, as those expected from presently developed free-electron lasers (Winick 1995; Wiik 1997), may provide structural information from large protein molecules and assemblies before radiation damage destroys them. Estimation of radiation damage as a function of X-ray photon energy, pulse length, integrated pulse intensity, and sample size was obtained in the framework of a radiation damage model, where the effects of atom–photon and ion–ion interaction were taken into account. Photons of 1 Å wavelength, corresponding to a photon energy of ∼12 keV, interact with atoms mainly through the photoelectric effect (Dyson 1973) (for carbon the photoelectric cross-section is ∼10 times higher than the corresponding elastic cross-section at this wavelength; Hubbel et al. 1980), and thus the photoelectric effect is the main source of radiation damage with X-rays.

Photoionization may proceed either through the ejection of an outer shell electron or through the ejection of an inner shell electron (Dyson 1973). Outer shell photo-events eject a single electron from the atom with an energy equivalent to the energy of the incoming photon minus the shell-binding energy and the recoil energy. With photon energies of ∼12 keV (or ∼1 Å wavelength), outer shell events are rare in carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur, and represent < 5% of all photoionization events.

A more frequent type of photoionization with X-rays involves the ejection of an inner shell electron from the atom (∼95–97% of photoionizations remove a K-shell electron from carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur). Typical K-hole lifetimes are of the order 1–10 fs (Krause and Oliver 1979), and the hollow ion relaxes through an electron falling from a higher shell into the vacant hole. In light elements, the energy of this electron is given to another electron, which is then also ejected from the atom through the Auger effect. Core ionization, however, constitutes a strong perturbation of the molecule, and may be accompanied by significant electronic effects (Siegbahn et al. 1969). First, the valence electrons often relax significantly to compensate for the presence of the positive core hole. The departing photoelectron can interact with these relaxing electrons, and lose kinetic energy in the process, thus forcing the system into an excited state (a process called shake-up). In some cases, the excitation may result in the ejection of low energy outer shell electrons from the atom (a process called shake-off). The multiple excitation lifetimes for light elements are comparable to core-hole lifetimes. The interaction between the outgoing electron and the remaining system depends on the chemical environment of the atom, and a description of these interactions requires quantum chemical calculations. The following key processes need to be taken into account.

Photoemission followed by single Auger decay

Ejected K-shell electrons with the highest possible kinetic energy correspond to a situation where the remaining system is left in the ground state, that is, the difference between the incoming photon energy and the energy of the ejected photoelectron equals the chemical binding energy and the recoil energy. In light elements like carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur, such clean photoemissions are followed by Auger emission, and the atom becomes doubly ionised (Krause and Oliver 1979). In heavier elements X-ray fluorescence dominates.

Shake-related processes

When photoionization ejects an inner shell electron so fast that the outer shell electrons have no time to relax, the situation gets similar to beta decay, whereby the nuclear charge suddenly increases by one unit. Quantum mechanics describes such a state as a superposition of proper eigen-states, which include states where one or more of the electrons may be unbound. Interactions between the departing photoelectron and the electrons left behind may reduce the kinetic energy of the photoelectron, and deposit energy into the system. The perturbation is called shake-up if they refer to an excitation in the final system, or shake-off if the result is the loss of one or more outer shell electrons from the ion. The relative contributions from these two processes have been found to be comparable in noble gases (Armen et al. 1985; Svensson et al. 1988; Wark et al. 1991). The following shake-related phenomena need to be considered.

Case a: Photoemission accompanied by shake-up excitation with Auger decay

This process reduces the energy of the photoelectron slightly (∼10–40 eV), and the energy difference can either be absorbed by the atom or added to the energy of the Auger electron. At the end, the atom becomes doubly ionized.

Case b: Photoemission accompanied by a shake-off event

In the vicinity of a hole, a vacancy and a free electron are created. The shake electron has ∼10–100 eV energy, and the atom becomes doubly ionized.

Case c: Photoemission accompanied by double Auger decay

This may proceed by different mechanisms, and may result in the triple ionization of the atom. These mechanisms include Auger cascading, single Auger decay combined with shake-off emission, and virtual inelastic scattering (for a full description, see Amusia et al. 1992). In this case, the energies of the two ejected electrons are asymmetrically distributed. For instance, for Ne (transition 1s−1 → 2s−2 2p−1 + q1+q2) the total available kinetic energy is ∼650 eV, and the most probable case is shaking off a slow electron and Auger emission of a fast electron with EShake-off ≪ EAuger (Amusia et al. 1992).

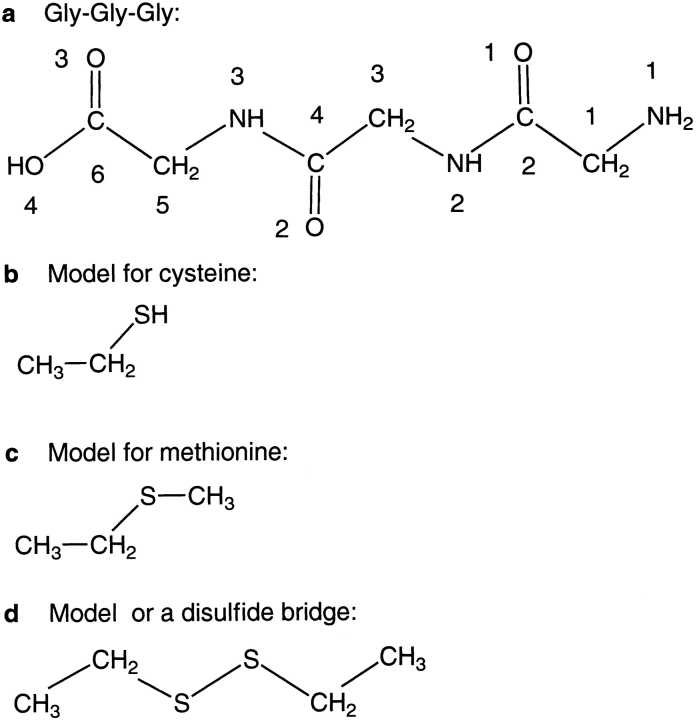

In the initial damage model of proteins (Neutze et al. 2000) only outer shell photoionization and inner shell photoionization with a subsequent Auger emission were taken into account. In the present paper we focus on photoionization mechanisms, including shake-up with a subsequent satellite photoionization (case a) and shake-off (cases b and c), which under certain conditions may produce multiple ionizations in the atom (case c). We investigate in detail what effects these processes may have on model compounds to assess radiation-induced damage processes in biological samples. We calculate the different shake contributions for carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen atoms in a model peptide (see Fig. 1a ▶). Shake effects for sulfur are estimated in separate calculations for the three most common chemical environments of sulfur in proteins (Cys, Met, Cys-S-S-Cys; Fig. 1b–d ▶).

Fig. 1.

The model compounds for calculating shake contributions in proteins. (a) The model peptide for calculations on carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen atoms. (b–d) Shake effects for sulfur were estimated from calculations on the three most common chemical environments of sulfur in proteins (Cys, Met, Cys-S-S-Cys).

Results

Figure 1 ▶ shows the model compounds used in the calculations. In a recent polymer study (Nakayama et al. 1999), experimentally observed differences in intensity for ester and carbonyl oxygen main lines could be explained directly from consideration of the main-line intensities, where the main-line intensity was estimated from the overlap obtained from the n = 0 term in equation (1). This has the clear advantage for inherently large molecules, such as polymers or polypeptides, that main-line losses can be estimated without consideration of all the shake states to which intensity is distributed. For large molecules, the number of shake states goes beyond that which can readily be calculated at the configuration interaction level of theory. In a Gly-Gly-Gly tripeptide (Fig. 1a ▶), the central glycine unit can be expected to display a shake spectrum that is similar to that of a residue within a longer polypeptide chain. To investigate effects arising from the truncations of the polypeptide chain, shake effects were calculated for all atoms in the model, including the atoms from the terminal carboxyl and amino functional groups.

There are six carbon atoms in the peptide model, showing very similar overlaps between the initial unionized state and the core ionized ground state (Table 1). This overlap is ∼0.85 for all carbons, except for the carbon at the terminal carboxylic acid group, which has an overlap of ∼0.87. The intensity loss from the main line is, therefore, close to ∼30% for all carbon atoms in these models (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overlaps (≤Ψ0|φ0>) and average total shake electron intensity (1-|≤Ψ0|φ0>|2)

| Atom | Overlap | Average shake intensity |

| C1 | 0.853 | 27% |

| C2 | 0.858 | |

| C3 | 0.850 | |

| C4 | 0.857 | |

| C5 | 0.853 | |

| C6 | 0.869 | |

| O1 | 0.776 | 38% |

| O2 | 0.773 | |

| O3 | 0.785 | |

| O4 | 0.823 | |

| N1 | 0.902 | 19% |

| N2 | 0.896 | |

| N3 | 0.897 |

Values were calculated for all carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen atoms occurring in the model polypeptide (Fig. 1A ▶).

The oxygen shake contribution is generally the largest. In particular, the carbonyl oxygens display large shake effects, in agreement with the general behavior for organic molecules. Here, strong shake is found for the two carbonyl oxygens in the peptide links, as well as for the double-bonded oxygen in the terminal carboxylate functional group. The overlap for these three oxygens is ∼0.78 (Table 1), corresponding to a total shake intensity loss of ∼40% (Table 1). The terminal hydroxyl oxygen has a slightly larger overlap of ∼0.82, corresponding to the main-line intensity loss of ∼33%.

There are two nitrogens in the peptide links, and one in a terminal amino group. The shake effect for all these atoms is similar: the overlap is ∼0.90 (Table 1) and the main-line loss is ∼20% (Table 1). Nitrogen shows the smallest shake contribution, and the results agree well with data on a polyimide polymer (Nakayama et al. 1999), which also showed little nitrogen shake effect.

Sulfur shake effects have been calculated for three different common chemical environments (Fig. 1b–d ▶; Table 2). The largest loss was found for a disulfide bridge (R-S-S-R, 25%), and the smallest one for the thiol terminal group (R-SH, 21%).

Table 2.

Total shake contributions (1-|≤Ψ0|φ0>|2) calculated for sulfur in three different chemical environments

| Molecule | Shake intensity |

| CH3CH2-SH | 21% |

| CH3CH2-S-CH2CH3 | 22% |

| CH3CH2-S-S-CH2CH3 | 25% |

| Average | 23% |

The initial models used for the sulfur calculations were smaller than the models used for the other atom types. This could, in principle, be a cause of concern, as these types of calculations are known to underestimate shake contributions in extended systems. To test the stability of the numerical results, additional calculations were performed on models with increasing chain lengths (CH3-SH, CH3-CH2-SH, and CH3-CH2-CH2-SH). The results indicated negligible drift (not shown).

Discussion

Radiation damage prevents the structural determination of single biomolecules and other nonrepetitive structures (like cells) at high resolutions in classic electron or X-ray-scattering experiments (Henderson 1990,Henderson 1995). Analysis of time-dependent components in damage formation suggests that the conventional damage barrier can be substantially extended at extreme dose rates and ultrashort exposure times (Neutze et al. 2000; Hajdu, 2000; Hajdu et al. 2000; Hajdu and Weckert 2001; Ziaja et al. 2001). A quantitative description of damage formation and a detailed analysis of the ionization dynamics of the sample are crucial for planning experiments at future X-ray lasers. Results described in this paper give the first assessments of shake contributions to the ionization of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur atoms within the most common chemical environments in a protein molecule. In previous applications, the calculated shake-up intensities were usually a few percentage units too high, therefore we judge the present results to provide upper bounds to the total shake intensities.

Data for noble gases show that shake-up and shake-off effects were of comparable magnitude (Armen et al. 1985; Svensson et al. 1988; Wark et al. 1991). Calculations on carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen by Mohammedein et al. 1993 and El-Shemi and Hassan 1997 show that photoemission accompanied by double Auger decay has nearly zero probability for these light elements. Such triple ionizations can thus be neglected in the ionization dynamics of C, O, N compounds. Sulfur, on the other hand, behaves differently, and the probability of multiple ionization (n > 2) after the ejection of a K-shell photoelectron is larger. The average charge left in sulfur after a single K-shell photoionization is estimated to be ∼4 (Mohammedein et al. 1993). For instance, for S: P(2) ∼5%, P(4) ∼34%, P(6) ∼3% (Mohammedein et al. 1993; El-Shemi and Hassan 1997). This implies that for sulfur, multiple ionization mechanisms should be taken into consideration to obtain more accurate predictions for the ionization dynamics of proteins.

The energy of the photoelectrons, which emerge from shake-up processes is similar to the energy of photoelectrons released during outer shell ionization (Nakayama et al. 1999). In these calculations the deviation was within 10–40 eV. As a consequence, these electrons can leave a submicroscopic sample in the same manner as outer shell photoelectrons. The inelastic mean free path of these electrons is of the order of a few hundred Angstroms (Ashley 1990 and references therein; Ziaja et al. 2001), and thus the damage by the departing electrons will only have to be considered in large samples where such electrons may become trapped and deposit energy.

Low energy shake-off electrons will behave similarly to Auger electrons, and may cause secondary ionization in the sample. A detailed analysis of secondary electron cascades elicited by low energy electrons can be found in Ziaja et al. 2001.

Materials and methods

The average total shake contributions were estimated from quantum chemical (QC) calculations, using the semiempirical INDO/S-CI program ZINDO, developed by Zerner and co-workers (Ridley and Zerner 1976; Bacon and Zerner 1979; Zerner et al. 1980), with standard parameterization. A single determinant description was used for the initial (unionized) state of the system, whereas the excited core-ionized states were obtained from Configuration-Interaction calculations with Single excitations (CIS). The equivalent core approximation was used to represent the core-ionized species.

The calculations are based on the sudden approximation (Åberg 1967) valid for high energy photons, in which the intensity of a given shake line is proportional to the square of the overlap <Ψ0|φn>:

|

(1) |

where Ψ0 is the wave function of the N-1 remaining electrons in the neutral molecule, and φn is the (N-1)-electron wave function of the nth state of the ionized system. These intensities were calculated with the SHAKEINT (Lunell 1987; Lunell and Keane 1988) program package. This method has been successfully applied to a wide range of systems, including organic molecules (Lunell et al. 1978; Sjoegren et al. 1992), C60 (Enkvist et al. 1995), polymers (PMDA-ODA polyimide) (Nakayama et al. 1999), and adsorbates on metals (CO adsorbed on Cu(100) surfaces) (Persson et al. 2000).

Acknowledgments

We thank Svante Svensson for illuminating discussions and David van der Spoel for excellent comments. This work was sponsored by the Swedish Natural Science Research Council (NFR), the Swedish Research Council for Engineering Sciences (TFR), the EU-BIOTECH Programme and in part by the Polish Committee for Scientific Research with grants Nos. 2 P03B 04718, 2 P03B 05119 to B.Z. A.S. was supported by a STINT distinguished guest professorship. B.Z. is supported by the Wenner-Gren Foundations.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/ps.26201.

References

- Åberg, T. 1967. Multiple excitation of a many-electron system by photon and electron impact. Ann. Acad. Sci. Fenn. Series A, VI. PHYSICA, Nr. 303.

- Amusia, M.Ya., Lee, I.S., and Kilin, V.A. 1992. Double Auger decay in atoms. Probability and angular distribution. Phys. Rev. A 45 4576–4587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armen, G.B., Åberg, T., Rezaul Karim, Kh., Levin, J.C., Crasemann, B., Brown, G.S., Hsiung Chen, M., and Ice, G.E. 1985. Threshold double photoexcitation of argon with synchrotron radiation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 54 182–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley, J.C. 1990. Energy-loss rate and inelastic mean free-path of low-energy electrons and positrons in condensed matter. J. Elec. Spec. Rel. Phenom. 50 323–334. [Google Scholar]

- Bacon, A.D. and Zerner, M.C. 1979. An intermediate neglect of differential overlap theory for transition metal complexes: Fe, Co and Cu chlorides. Theor. Chim. Acta 53 21–54. [Google Scholar]

- Dyson, N.A. 1973. X-rays in atomic and nuclear physics. Longman, London, UK.

- El-Shemi, A. and Hassan, A.S. 1997. Ejection probabilities of electrons as result of reorganization effects of inner-shell ionized atoms. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. (Part 1) 36 3726–3729. [Google Scholar]

- Enkvist, C., Lunell, S., Sjögren, B., Brühwiler, P.A., and Svensson, S. 1995. The C1s shakeup spectra of buckminsterfullerene, acenaphthylene, and naphtalene, studied by high resolution X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and quantum mechanical calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 103 6333–6342. [Google Scholar]

- Hajdu, J. 2000. Single molecule X-ray diffraction. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 10 569–-573. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hajdu, J. and Weckert, E. 2001. Life Sciences — Scientific applications of XFEL radiation. TESLA, the Superconducting Electron-Positron Linear Collider with an integrated X-ray Laser Laboratory. Technical Design Report., DESY, ISBN 3-935702-00-0 5: 150–168.

- Hajdu, J., Hodgson, K., Miao, J., van der Spoel, D., Neutze, R., Robinson, C., Faigel, G., Jacobsen, C., Kirz, J., Sayre, D., Weckert, E., Materlik, G., and Szöke, A. 2000. Structural studies on single particles and biomolecules. LCLS: The First Experiments. SSRL, SLAC, Stanford, CA.

- Henderson, R. 1990. Cryoprotection of protein crystals against radiation-damage in electron and X-ray diffraction. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Biol. Sci. 241 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1995 The potential and limitations of neutrons, electrons and X-rays for atomic resolution microscopy of unstained biological molecules. Q. Rev. Biophys. 28 171–193. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hubbel, J.H., Gimm, H.A., and Overbo, I. 1980. Pair, triplet, and total atomic cross-sections (and mass attenuation coefficients) for 1MeV–100GeV photons in elements Z = 1 to 100 . J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 9 1023–1045. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, M.O. and Oliver, J.H. 1979. Natural width of atomic K and L level K_alpha X-ray lines and several KLL Auger lines. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 8 329–338. [Google Scholar]

- Lunell, S. 1987. Technical Report No. 892. Dept. of Quantum Chemistry, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden.

- Lunell, S. and Keane, M.P. 1988. UUIP Report No. 1183. Institute of Physics, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden.

- Lunell, S., Svensson, S., Malmqvist, P.A., Gelius, U., and Siegbahn, K. 1978. A theoretical and experimental study of the carbon 1s shakeup structure of benzene. Chem. Phys. Lett. 54 420–424. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammedein, A.M.M., Reiche, I., and Zschornack, G. 1993. Z-dependences in the reorganization of inner-shell ionized atoms. Radiat. Eff. Defect. S. 126 309–312. [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama, Y., Persson, P., Lunell, S., Kowalczyk, S.P., Wannberg, B., and Gelius, U. 1999. High resolution X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and INDO/S-CI study of the core electron shakeup states of pyromellitic dianhydride-4,4′-oxydianiline polyimide . J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 17 2791–2799. [Google Scholar]

- Neutze, R., Wouts, R., van der Spoel, D., Weckert, E., and Hajdu, J. 2000. Potential for biomolecular imaging with femtosecond X-ray pulses. Nature 406 752–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson, P., Bustad, J., and Zerner, M.C. 2000. INDO calculations of small copper clusters, and CO adsorbed on copper (100) surfaces . J. Comp. Chem. 21 1221–1228. [Google Scholar]

- Ridley, J. and Zerner, M.C. 1976. Triplet states via intermediate neglect of differential overlap: Benzene, pyridine and the diazines . Theor. Chim. Acta 42 223–236. [Google Scholar]

- Siegbahn, K., Nordling, C., Johansson, G., Hedman, J., Heden, P.F., Hamrin, K., Gelius, U., Bergmark, T., Werme, L.O., Manne, R., and Baer, Y. 1969. ESCA applied to free molecules. North Holland, Amsterdam

- Sjögren, B., Svensson, S., de Brito, A.N., Correia, N., Keane, M.P., Enkvist, C., and Lunell, S. 1992. The C1s core shake-up spectra of alkene molecules: An experimental and theoretical study. J. Chem. Phys. 96 6389–6398. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, S., Eriksson, B., Martensson, N., Wendin, G., and Gelius, U. 1988. Electron shake-up and correlation satellites and continuum shake-off distributions in X-ray photoelectron-spectra of the rare-gas atoms. J. Elec. Spec. Rel. Phenom. 47 327–384. [Google Scholar]

- Wark, D.L., Bartlett, R., Bowles, T.J., Robertson, R.G.H., Sivia, D.S., Trela, W., Wilkerson, J.F., Brown, G.S., Crasemann, B., Sorensen, S.L., Schaphorst, S.J., Knapp, D.A., Henderson, J., Tulkki, J., and Åberg, T. 1991. Correspondence of electron spectra from photoionization and nuclear internal conversion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67 2291–2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiik, B.H. 1997. The TESLA project: An accelerator facility for basic science. Nucl. Inst. Meth. Phys. Res. B 398 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Winick, H. 1995. The linac coherent light source (LCLS): A fourth generation light source using the SLAC linac. J. Elec. Spec. Rel. Phenom. 75 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zerner, M.C., Loew, G.H., Kirchner, R.F., and Mueller-Westerhoff, V.T. 1980. An intermediate neglect of differential overlap technique for spectroscopy of transition-metal complexes. Ferrocene . J. Am. Chem. Soc. 102 589–599. [Google Scholar]

- Ziaja, B., van der Spoel, D., Szöke, A., and Hajdu, J. 2001. Auger-electron cascades in diamond and amorphous carbon. Phys. Rev. B (in press).