Abstract

The variable adherence-associated (Vaa) adhesin of the opportunistic human pathogen Mycoplasma hominis is a surface-exposed, membrane-associated protein involved in the attachment of the bacterium to host cells. The molecular masses of recombinant 1 and 2 cassette forms of the protein determined by a light-scattering (LS) method were 23.9 kD and 36.5 kD, respectively, and corresponded to their monomeric forms. Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy of the full-length forms indicated that the Vaa protein has an α-helical content of ∼80%. Sequence analysis indicates the presence of coiled-coil domains in both the conserved N-terminal and antigenic variable C-terminal part of the Vaa adhesin. Experimental results obtained with recombinant proteins corresponding to the N- or C-terminal parts of the shortest one-cassette form of the protein were consistent with the hypothesis of two distinct coiled-coil regions. The one-cassette Vaa monomer appears to be an elongated protein with a axial shape ratio of 1:10. Analysis of a two-cassette Vaa type reveals a similar axial shape ratio. The results are interpreted in terms of the topological organization of the Vaa protein indicating the localization of the adherence-mediating structure.

Keywords: Coiled coil, bacterial surface protein, Mycoplasma hominis, Vaa, adhesin

The mycoplasmas are the smallest self-replicating organisms known and are characterized by the lack of a protecting cell wall, which exposes the plasma membrane and the proteins embedded in it to the surrounding environment. Human and animal mycoplasmas are often observed as infectious agents of the mucosal barriers of their hosts. A pronounced variation of surface proteins is observed among the mycoplasmas, and this is thought to mediate evasion of the humoral immune response, resulting in the often chronic nature of mycoplasmal infections (Razin et al. 1998). Mycoplasma hominis is an opportunistic human pathogen primarily associated with urogenital and neonatal infections, although extragenital infections of blood, joints, skin, and other tissues have also been observed (Ladefoged 2000).

The variable adherence-associated (Vaa) antigen of M. hominis is involved in the adherence of the bacterium to host cells (Zhang and Wise 1997; Henrich et al. 1993). Adherence of M. hominis cells to host cells is crucial for subsequent colonization and infection. The Vaa protein is highly abundant on the M. hominis surface, but ON/OFF switching of expression is observed with a frequency of 10−3–10−4, which is thought to promote the spread of the bacterium (Zhang and Wise 1997). Six distinct vaa gene types are present in clinical isolates (Boesen et al. 1998; Henrich et al. 1998). The diversity of Vaa is determined by the variable number and composition of homologous exchangeable cassettes located in the C-terminal part of the protein (Zhang and Wise 1996; Boesen et al. 1998). The individual cassette has an average length of 110 amino acids (aa), and each cassette contains a coiled-coil motif (Henrich et al. 1996; Boesen et al. 1998). The cassette organization of Vaa is believed to arise from a combination of duplications and deletions of cassettes in some M. hominis isolates and recombination of cassettes between M. hominis isolates (Boesen et al. 1998; Henrich et al. 1998).

The coiled coils are characterized by the presence of amino acid heptad repeats, in which isofunctional residues alternate in such a way that hydrophobic residues occupy the first and fourth positions, called a and d, and hydrophilic residues hold the remaining positions, b, c, e, f, and g (Lupas 1996). The hydrophobic residues of one α-helix containing heptad repeats interact with hydrophobic residues in heptad repeats located on other α-helices. This interaction is characterized by a knobs-into-holes packing, wherein a hydrophobic residue from one helix is surrounded by four hydrophobic residues from another helix. The coiled-coil motif has been identified in a number of proteins including bacterial and viral membrane proteins. Most of these extracellular coiled coils are involved in the pathogenesis of the microorganisms.

Here we describe the analysis of a range of recombinant Vaa proteins to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the structure of Vaa. Furthermore, to understand the role of multiple cassettes, we analyzed two distinct Vaa types represented by the vaa genes from the M. hominis isolates 5941 and 4195 (Boesen et al. 1998). These Vaa types harbor one and two cassettes, respectively. Light scattering and CD were used to analyze tertiary and secondary structure of the full-length protein as well as recombinants comprising only predicted N- or C-terminal coiled-coil regions.

Results

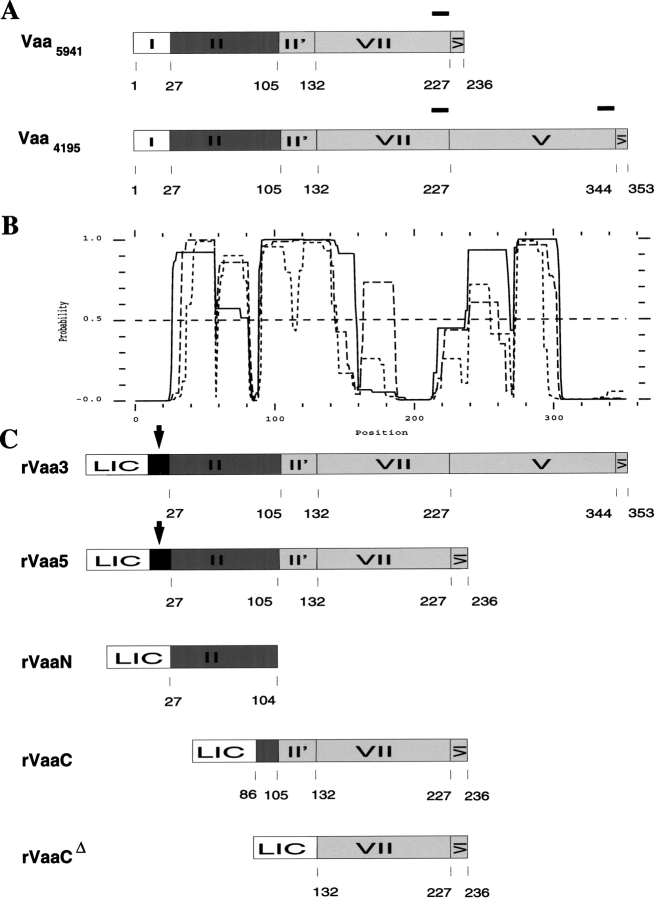

Prediction of coiled-coil regions in Vaa

The program Coilscan based on the matrix by Lupas (1996) was used to identify coiled-coil motifs in Vaa proteins. The previous identification of the coiled-coil motif located in each of the C-terminal cassettes was based on sequence alignments that contain a conservation of isoleucine/leucine residues for every seventh residue (Henrich et al. 1996; Boesen et al. 1998). This cassette coiled-coil region was also identified by Coilscan using window sizes of 28, 21, and 14 aa (Fig. 1 ▶). In all cassette sequences presently available the coiled-coil region was located primarily in the N-terminal part and spanned ∼2/3 of the cassette. But ∼30 aa in the C-terminal part of each cassette did not contain a coiled-coil motif, indicating another structure in this region (Fig. 1 ▶).

Fig. 1.

Schematic drawing of constructs and coiled-coil regions. (A) Modular structure of native category 5 Vaa of M. hominis 5941 (Vaa5941) and category 3 Vaa of M. hominis 4195 (Vaa4195). The signal peptide, module I, is cleaved off in the mature Vaa, and the N-terminal cysteine (C27) is lipid-modified. Modules II and VI are highly conserved in all the Vaa types. The C-terminal part of Vaa5941, comprising modules II' and VII, is highly variable. The structure of Vaa4195 resembles that of Vaa5941 with the exception of an additional C-terminal cassette, module V. The modules V and VII are exchangeable cassettes. The regions with tryptophan encoded by UGA codons are shown with bars above the schematic drawings of Vaa5941 and Vaa4195. (B) Output from Coilscan using a window of 28 (solid line), 21 (dashed line), or 14 (dotted line) residues. The diagram shows the probability for the presence of coiled-coil regions in Vaa from M. hominis 4195. The probability of coiled coil is high throughout most of the native Vaa4195. Similar coiled-coil regions were observed for the corresponding part of Vaa5941. A threshold value of 0.5 is shown as a horizontal dashed line. (C) The full-length recombinant category 3 Vaa (rVaa3), category 5 Vaa (rVaa5), and the N- and C-terminal rVaa fragments called rVaaN and rVaaC, respectively. The rVaaN and the rVaaC/Cδ proteins contain the N-terminal and C-terminal parts of category 5 Vaa, respectively. A fusion peptide of 6.5 kD (LIC-tag + thrombin site and monoclonal antibody 35.2 epitope, see Materials and Methods) is present in the N-terminal part of the rVaa3 and rVaa5 proteins, and the LIC-tag (5 kD) is fused to the rVaaN, rVaaC, and rVaaCδ proteins. The arrows indicate the thrombin-cleavage site for removal of LIC-tag in rVaa5 and rVaa3. The numbering corresponds to native Vaa.

For the shortest Vaa type (from M. hominis 5941) containing only one cassette in the C terminus, two major coiled-coil regions were identified by Coilscan (Fig. 1 ▶). The C-terminal coiled-coil region was predicted to encompass residues 90–159 beginning in the conserved region (module II) and extending through the module II' into the cassette part, module VII (Fig. 1 ▶). Using a window size of 21 aa, this region was extended to residue 186 (Fig. 1 ▶). Furthermore, the 14-aa window scan predicted an additional coiled-coil region from residues 223 to 236. A previously unknown coiled-coil region was also identified in the conserved N-terminal part of Vaa and shown to extend throughout the conserved region from residue 28 to 82 (Fig. 1 ▶).

By alignment of the amino acid sequences of the conserved regions deduced from the vaa genes, two highly conserved prolines were identified (P59 and P89), one located in the middle of the N-terminal coiled-coil (P59) region and the other located immediately downstream of the N-terminal coiled-coil region (P89). When the scan for coiled-coil regions was performed with window sizes of 14 and 21 residues, the N-terminal coiled-coil region was divided into two coiled-coil regions with a low probability of coiled coil at the proline position (Fig. 1 ▶).

The Vaa type of M. hominis 4195 showed the presence of an additional coiled-coil region (aa 238–305) located in the C-terminal part of the protein corresponding to the additional cassette, module V (Fig. 1 ▶). The interactions between the predicted N-terminal and C-terminal coiled-coil regions in Vaa and their possible influence on the structure or oligomeric state of the protein were investigated experimentally.

Cloning and purification of Vaa

The UGA stop codon encodes tryptophan in mycoplasmas. Therefore, to clone and express a tryptophan-containing mycoplasmal protein in a heterologous host like E. coli, site-directed mutagenesis is necessary (Fig. 1 ▶). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed by PCR, and the resulting PCR products were used for LIC-cloning (see Materials and Methods). Expression was performed in E. coli BL21 (DE3). Five recombinant constructs were made (Fig. 1 ▶). The full-length form (aa 27–353) of Vaa from M. hominis 4195 (Vaa4195) was called rVaa3, as Vaa4195 belongs to the category 3 Vaa type (Boesen et al. 1998). This construct was made as a mature form of Vaa, and therefore the signal peptide (aa 1–26) was not included. Vaa 4195 contains two cassettes termed modules V and VII. The C-terminal cassette, module V, is followed by 10 highly conserved amino acid residues (module VI) present in the C-terminal sequence of all Vaa types. Another construct originates from mature Vaa5941 and therefore lacks module V (Fig. 1 ▶). It was called rVaa5 and was made by cloning the part of the M. hominis 5941 vaa gene encoding aa 27–236 (Fig. 1 ▶). Furthermore, the conserved N-terminal part (rVaaN) and C-terminal cassette part (rVaaC and rVaaCδ) of rVaa5 were cloned. These constructs contained the N-terminal and C-terminal coiled-coil regions, respectively (Fig. 1 ▶). As a consequence of the cloning procedure and the cloning vector, the recombinant Vaa proteins were fused to an N-terminal 5-kD peptide (termed LIC-tag, see Materials and Methods) including a His-tag. Following expression, purification on a Ni2+ column under nondenaturing conditions resulted in >90% pure proteins. The LIC-tag was removed from purified rVaa5 and rVaa3 by cleavage with thrombin. The resulting proteins were called rVaa5T and rVaa3T.

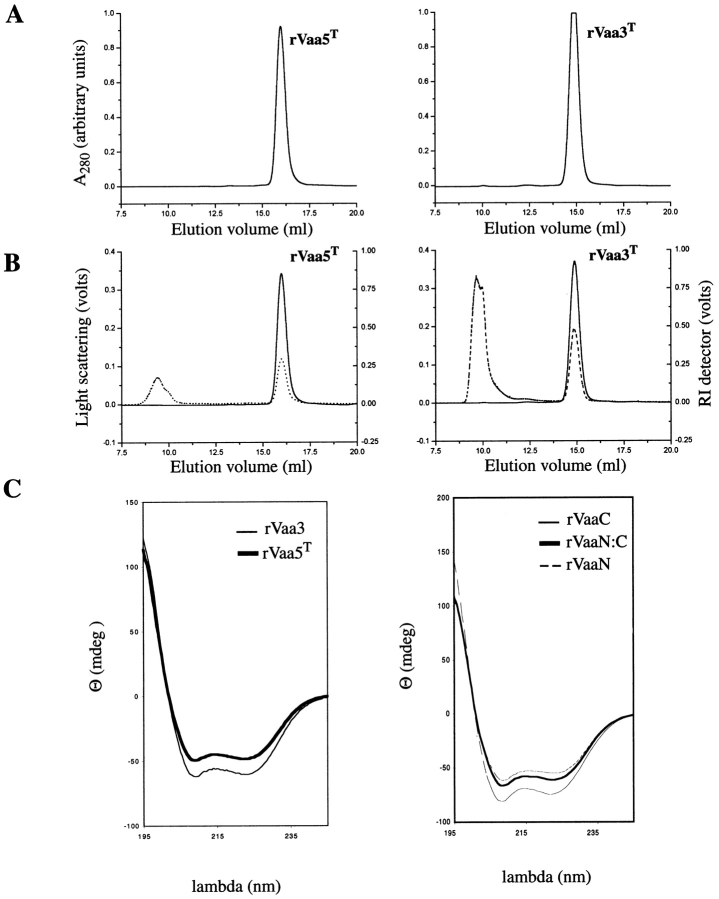

Vaa is a monomer

Gel filtration chromatography of rVaa5T and rVaa3T in physiological buffer revealed a single peak for both samples (Fig. 2 ▶). The apparent molecular masses calculated from the retention times were 77 kD and 160 kD, respectively. Because the theoretical molecular masses for the monomers are 25 kD and 38.5 kD, the result indicated a high degree of protein oligomerization for both forms. These calculations, however, are based on the calibration of the column with globular standard proteins and assume a globular structure for the rVaa proteins. We therefore applied a laser light-scattering method coupled to the gel filtration column to provide the absolute molecular mass for the macromolecules in solution. The molecular masses were then found to be 23.9 kD and 36.5 kD, in agreement with the theoretically calculated molecular masses for the monomer forms. The rVaaN, rVaaC, and rVaaCδ proteins all appeared in a monomeric form with molecular masses of 14.8 kD, 21.5 kD, and 19.3 kD, respectively. Correspondingly, the calculated theoretical molecular masses of these proteins are 13.5 kD, 22 kD, and 18 kD.

Fig. 2.

Gel filtration, light scattering, and circular dichroism of rVaa. (A) Gel filtration of rVaa5T and rVaa3T (left and right panels, respectively) using a TSK-gel G3000SW column. The plots show single, monodisperse peaks. (B) Chromatogram for 90° light scattering (dashed line) contrasted with the refractive index (RI) signal (solid line). A peak was observed at V0 (8.6 mL) for both proteins in the light-scattering detector. This was not protein as judged from the UV and RI detectors, but probably dust particles. A second peak observed for both detectors comigrated with the UV peak. (C, left) CD spectra of the rVaa5T (thick line) and rVaa3 (thin line) constructs. (Right) CD spectra of rVaaN (dashed line), rVaaC (thin solid line), and the stoichiometric rVaaN:C mixture (thick solid line).

The contradiction between the retention time and the molecular mass of the species points to a nonglobular, perhaps elongated structure of the Vaa protein. Because the scattering of the applied light (wavelength 690 nm) by such small molecules is isotropical, we cannot obtain information about their size from the static experiment. The shape of the molecule, however, has a pronounced effect on the translational diffusion coefficient, measured in dynamic light-scattering experiments. The results of the hydrodynamic analysis are summarized in Table 1. The rVaa3T and rVaa5T proteins have a hydrodynamic radius (Rh) of 39 Å and 33 Å, respectively. rVaaN has an Rh of 21 Å, and rVaaC and rVaaCδ have Rh of 30 Å and 28 Å, respectively. These results were further confirmed by calculation of the hydrodynamic radii of rVaa3T and rVaa5T from their retention times in gel filtration, giving very similar Rh values (41.5 Å and 35.5 Å, respectively). Using a theoretically calculated partial specific volume (Table 1) for each construct, the frictional ratios (f/f0) were calculated assuming 40% hydration (Cantor and Schimmel 1980). From the frictional ratio, the axial shape ratio of the corresponding prolate ellipsoid was found. The axial shape ratios were very similar for rVaa3T, rVaa5T, rVaaC, and rVaaCδ, being 1:11, 1:10, 1:9, and 1:9, respectively. This indicates an elongated structure typical of fibrous proteins. In contrast, the axial shape ratio of rVaaN is 1:4, similar to that of globular proteins such as lysozyme and serum albumin (Tanford 1961).

Table 1.

Hydrodynamic data

| rVaa construct | Rh |

|

f/f0b | Axial shape ratio | |

| rVaa3T | 39 Å | 0.708 | 1.58 | 1:11 | |

| rVaa5T | 33 Å | 0.674 | 1.56 | 1:10 | |

| rVaaN | 21 Å | 0.715 | 1.20 | 1:4 | |

| rVaaC | 30 Å | 0.706 | 1.46 | 1:9 | |

| rVaaCδ | 28 Å | 0.702 | 1.48 | 1:9 |

(Rh) Hydrodynamic radius obtained from dynamic light scattering measurements.

a Calculated from Table 4.3 in Creighton (1993). Partial specific volume  is in cm3/g.

is in cm3/g.

b The frictional ratio (f/f0) was calculated from Rh, and the theoretical molecular weight of the constructs as Rh/3

and the theoretical molecular weight of the constructs as Rh/3 Mw/4πNA)1/3 and an assumption of 40 percent hydration.

Mw/4πNA)1/3 and an assumption of 40 percent hydration.

Secondary structure of Vaa

CD spectra indicated primarily α-helical structures for all Vaa proteins (Fig. 2C ▶). The α-helical contents of the full-length proteins rVaa3 and rVaa5 (both containing the LIC-tag) and of rVaa5T were calculated to be ∼76%, 75%, and 83%, respectively. Therefore, the LIC-tag has an α-helical content of 38%. This indicates identical α-helical content for the Vaa 3 and 5 types.

The α-helical contents of the N- and C-terminal fragments (rVaaN and rVaaC) were 63% and 77%, respectively. Calculation of the contribution of α-helical content from the Vaa parts of these constructs using an α-helical content of the LIC-tag of 38% yielded an α-helical content of ∼77% and ∼88% for rVaaN and rVaaC, respectively, which agrees well with the helical content of full-length Vaa.

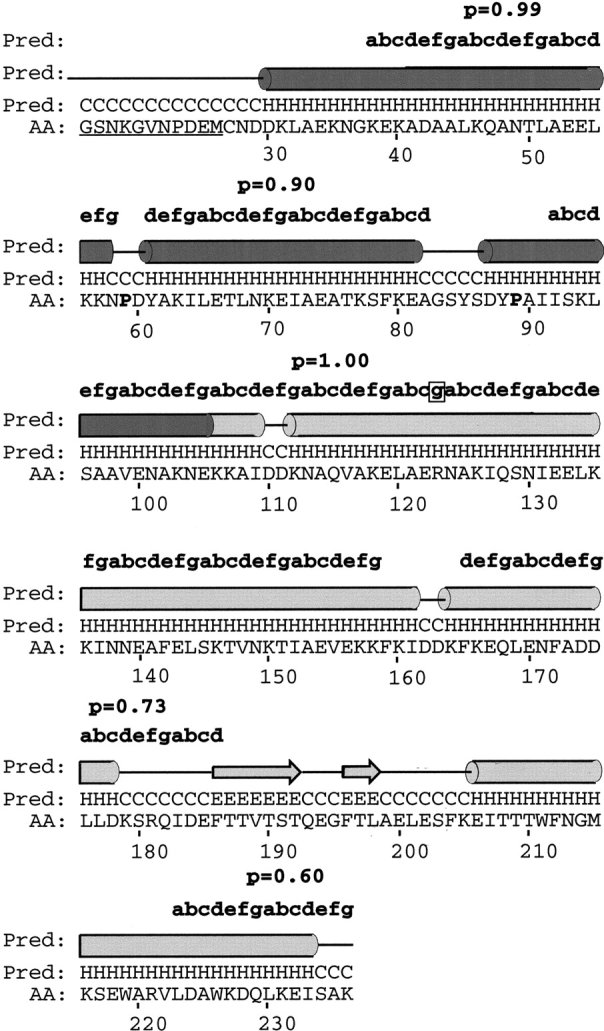

The conserved N-terminal part (aa 27–105 in native Vaa, Fig. 1 ▶) of Vaa was subjected to secondary structure analysis by the Jpred2 server (Cuff et al. 1998). This region was predicted to be highly α-helical, containing three α-helices interrupted by short breaks in helicity. For the secondary structure prediction of the cassette part of Vaa, multiple alignment of all cassette sequences available in the databases was performed, and the alignment was submitted to the Jpred2 server. Two α-helices followed by two β-sheets and an α-helix was predicted for this region. The two consensus predictions superimposed on the amino acid sequence of the rVaa5T construct are shown in Figure 3 ▶. The analysis shows an overall α-helical secondary structure, in good agreement with the CD data. Furthermore, the Jpred2 consensus prediction indicates the presence of three helices in the conserved N-terminal region. The conserved prolines P59 and P89 (Fig. 3 ▶) are located on either side of the second helix. The secondary structure prediction also implies the presence of two helical regions separated by a short β-sheet region in the C-terminal cassette part of Vaa. The helical regions overlap with the predicted coiled-coil regions as shown in Figure 3 ▶. The heptad repeat contained a stutter in the module II' region bordering module VII (Figs. 1, 3 ▶ ▶). A short break in helicity was observed between the two first α-helices of the cassette. This region corresponds to a part of the cassettes for which insertions/deletions (indels) are observed when aligning the cassette sequences (Henrich et al. 1996; Boesen et al. 1998). In the module V sequence an insertion of 8 aa is observed compared to other cassette sequences.

Fig. 3.

Secondary structure prediction of Vaa using the Jpred2 server (Cuff et al. 1998). The N-terminal part and a multiple alignment of cassette sequences from Vaa were subjected to secondary structure prediction, and the results were superimposed on the rVaa5T sequence. The prediction is shown in letter code (H, α-helix; E, β-sheet; C, coil) and schematically (tube, α-helix; arrow, β-sheet; line, coil). Above the schematic illustration the heptad repeats revealed by Coilscan are shown with probabilities (p). The two conserved prolines (corresponding to P59 and P89 in native Vaa) are shown in boldface. A stutter (boxed) is observed at R123, and a break in α-helicity corresponding to an indel region is observed at D162 in the rVaa5T sequence. The fusion-peptide part of rVaa5T is underlined. Shading and numbering is according to Figure 1 ▶.

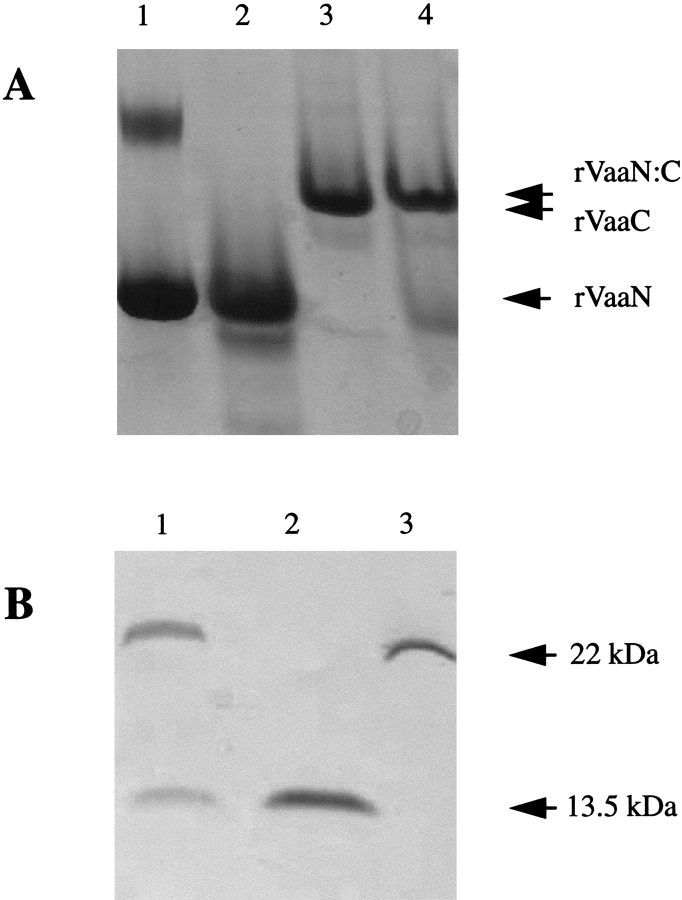

Interaction of coiled-coil regions

The rVaa5 protein is a monomer in solution, and this raises the possibility of an intramolecular interaction between the coiled-coil regions of the N- and C-terminal parts. To test for this interaction, rVaaN and rVaaC fragments were mixed in a 1:1 ratio and incubated at 3°C, 21°C, and 37°C for 1 h. The individual fragments and the mixture were subjected to native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. One major band was observed for both the rVaaN and the rVaaC fragments (Fig. 4A ▶, lanes 2,3). A small shift in migration for the rVaaC band was observed, and the band corresponding to rVaaN disappeared in the mixture at all incubation temperatures (Fig. 4A ▶, lane 4). To find the composition of the shifted band, bands were excised from the native gel and boiled in SDS-sample buffer. Subsequent SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis revealed that the shifted band contained both rVaaN and rVaaC fragments (Fig. 4B ▶, lane 1) when compared with the individual rVaaN and rVaaC bands excised from the native gel (Fig. 4B ▶, lanes 2 and 3, respectively). The rVaaN and rVaaC bands from lanes 2 and 3 (Fig. 4A ▶) were subjected to the same treatment and used as controls in Figure 4B ▶. These observations showed an interaction between rVaaN and rVaaC.

Fig. 4.

Native and SDS-PAGE of the rVaaN, rVaaC, and rVaaN:C fragments. (A) Nondenaturing gel of the rVaaN (lane 2), rVaaC (lane 3), and a mixture of rVaaN and rVaaC (lane 4) proteins, showing a new band slightly above the position of the rVaaC band (lane 4). Lane 4 has two bands because of excess amounts of rVaaN. The BSA standard is shown in lane 1, and BSA monomer and dimer bands are also observed. (B) The dominating bands from lanes 2–4 of A were excised from the nondenaturing gel, boiled in SDS-sample buffer, and used for SDS-PAGE. The top band extracted from lane 4 of A (rVaaN:C) contained two protein subunits as revealed by SDS-PAGE (lane 1) corresponding to the rVaaN (lane 2) and rVaaC (lane 3) proteins with molecular masses of 13.5 kD and 22 kD, respectively.

Furthermore, rVaaN, rVaaC, and a stoichiometric mixture (rVaaN:C) was used for recording CD spectra. This showed that the rVaaN:C spectrum was intermediate between the CD spectra of the individual rVaaN and rVaaC fragments and that the shape of the CD spectrum is identical to that of the spectrum of full-length rVaa (Fig. 2B ▶). The ratios of the ellipticities at 222 to 208 nm were 0.897, 0.923, and 0.924 for rVaaC, rVaaN, and rVaaN:C, respectively. The Θ222/208 ratio of the stoichiometric mixture of rVaaN and rVaaC was higher than the Θ222/208 ratio of the rVaaC, and similar to the Θ222/208 ratio for rVaaN. This may indicate an increase in coiled-coil content for the mixture (Cooper and Woody 1990; Greenfield and Hitchcock-Degregori 1993; Nomizu et al. 1996). When the same experiments were performed with rVaaN and rVaaCδ fragments, no interaction was observed. In fact, the Θ222/208 ratio of the rVaaN:Cδ mixture decreased. These results indicate that the part of rVaaC interacting with rVaaN is located in the N-terminal region (Fig. 1 ▶).

Discussion

Our data indicate that Vaa belongs to the group of monomeric microbial surface-exposed coiled-coil proteins that also includes Protein A of staphylococci (Tashiro et al. 1997). This is in contrast to a previous suggestion based on sequence predictions that Vaa could form an oligomer (Henrich et al. 1996). The data indicate that Vaa is an elongated protein with an axial shape ratio of ∼1:10. A similar axial shape ratio of 1:12 was observed for the pspA protein of Streptococcus pneumoniae, and a model was proposed in which the protein folded back on itself, forming a coiled coil (Jedrzejas et al. 2000). In comparison, tropomyosin, an actin-associated protein with a size similar to pspA (284 aa in tropomyosin vs. 303 aa in PspA) has an axial shape ratio of 1:20 and is a dimeric coiled coil. Similarly, rVaa5T has 221 aa and an axial shape ratio of 1:10, which indicates that Vaa probably also folds back on itself. The N-terminal part (rVaaN) has an axial shape ratio of 1:4, and the C-terminal parts (rVaaC and rVaaCδ) have axial shape ratios similar to full-length Vaa. This indicates that the C-terminal part of Vaa is elongated, whereas the N-terminal part is globular.

The prediction of three short helices (supported by the CD data) with proline-containing loop regions in combination with a shape axial ratio of 1:4 indicates that the N-terminal part of Vaa forms a triple-helical coiled coil. This is supported by the interactions of rVaaN and rVaaC. rVaaC contains the third helix of the conserved N-terminal part. Most of the third helix is also present in the rVaaN construct (Fig. 1 ▶). This part is not present in rVaaCδ, which does not interact with rVaaN. Furthermore, it is possible that the N-terminal part of the II' region is involved in the interaction between rVaaN and rVaaC, as the third helix extends into this region (Fig. 3 ▶). The heptad repeat of the II' region contains a stutter (Fig. 3 ▶, boxed), which might indicate the transition from the N-terminal to the C-terminal coiled-coil region.

The interaction of rVaaN and rVaaC appears to reconstitute Vaa as judged by the shape of the CD spectrum of the rVaaN:C complex compared with full-length Vaa. The fold of the N-terminal part of Vaa resembles the individual coiled-coil domains of protein A, although the helices are predicted to be slightly longer (Tashiro et al. 1997). Using the predicted secondary structure, a fold such that the second helix folds back on the first with the β-sheet region forming a turn fits the data best for the C-terminal part.

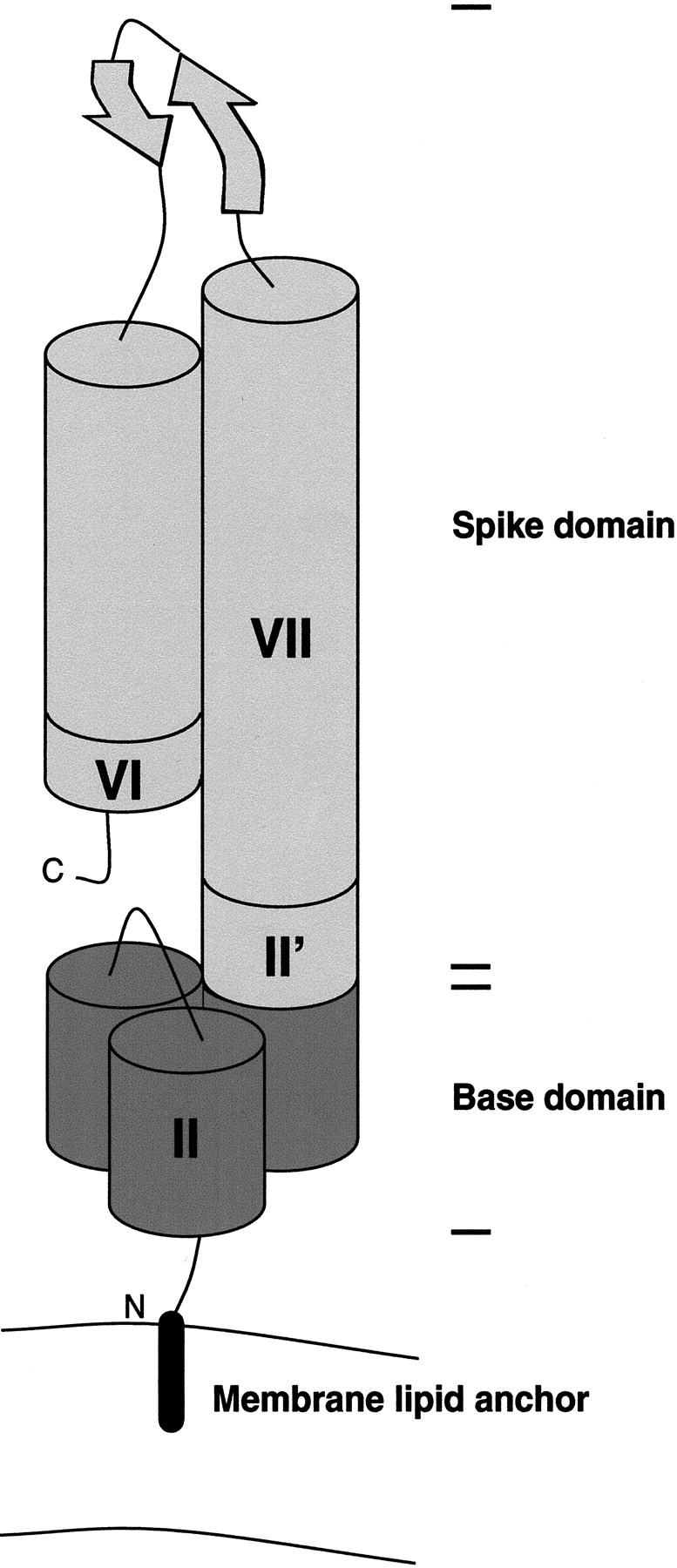

A hypothetical model for the topology of Vaa is shown in Figure 5 ▶. The model shows the bacterial membrane lipid anchor, typical of procaryotic lipoproteins, which is attached to the N-terminal cysteine residue of mature Vaa. The conserved N-terminal part folds into a triple-helix bundle, and the protein extends into an elongated helix, with the two β-sheets forming a loop region and a C-terminal helix folding back on the elongated helix. Using a rise of 1.5 Å per helical residue (Burkhard et al. 2000) and the Jpred2 α-helix prediction, this model would give a length of ∼160 Å and a diameter of ∼20 Å, characteristic of dimeric and trimeric coiled coils, yielding an axial shape ratio of 1:8, which is in good agreement with our data. The model indicates that Vaa is composed of an N-terminal base domain in close proximity to the membrane and a C-terminal spike cassette domain projecting out from the surface of the mycoplasma (Fig. 5 ▶).

Fig. 5.

Model of the one-cassette Vaa protein. The numbering of modules is according to Figure 1 ▶, and the shading is according to Figures 1 and 3 ▶ ▶. (Not to scale.)

The calculated length of Vaa is very similar to the coiled-coil domain of cortexillin I, which was measured to be 190 Å by electron microscopy (Steinmetz et al. 1998). The crystal structure of this domain was recently solved by X-ray crystallography and was shown to be a dimeric coiled coil (Burkhard et al. 2000). Calculation of the hydrodynamic radius from the sedimentation data given by Steinmetz et al. (1998) gives a value of 31 Å, which is comparable to the value for the Rh of rVaa5T of 33 Å. The dimeric coiled-coil domain of cortexillin I has a molecular mass of 27.3 kD, closely similar to the 25 kD of rVaa5T.

The distinct Vaa types are characterized by different numbers and configurations of cassettes. Zhang and Wise (1996) proposed that the addition of a cassette could create a more elongated protein. However, gel filtration retention times and dynamic light-scattering data on rVaa3T and rVaa5T indicates that this is not the case. The axial shape ratios of the two-cassette rVaa3T protein and the one-cassette rVaa5T protein are almost identical. This indicates that the cassettes are arranged in parallel and not end-to-end. This also agrees with and supports our model (Fig. 5 ▶).

The model intriguingly indicates that the predicted β-sheet region of the cassette is located most distant to the surface of the bacterium. It is thus plausible that this region contains the adherence-mediating structure of Vaa. Supporting this, Henrich and coworkers (Henrich et al. 1993) found that two monoclonal antibodies were able to inhibit M. hominis adhesion to HeLa cells. The monoclonal antibodies recognized epitopes located in the indel region of different cassettes in the same Vaa type. The indel region is located close to the predicted β-sheet turn region, and it is likely that the antibodies would sterically block the interaction with host cell receptors.

The different Vaa types display a varying number of cassettes. The presence of additional cassettes would bring additional binding sites in close proximity and increase binding affinity. This is in agreement with the results of Kitzerow et al. (1999), who showed that the adherence function was preserved in different recombinant combinations of cassettes, indicating that the adherence-mediating structure was present in each individual cassette. Furthermore, a two-cassette fragment was shown to display higher affinity than a one-cassette fragment for HeLa cells (Kitzerow et al. 1999). Additionally, two cassettes exhibit higher inhibitory effects on the adherence of a native three-cassette Vaa type to HeLa cells compared with the one-cassette fragment (Kitzerow et al. 1994).

Interestingly, the Vaa type most commonly observed in M. hominis isolates is the three-cassette category 1 form (Boesen et al. 1998; Henrich et al 1998). According to the above speculations, this Vaa type would display three binding sites by analogy to influenza hemagglutinin (Weis et al. 1988) and a number of other viral trimeric coiled-coil surface proteins. In many cases this might be the optimal conformation.

A common feature of the coiled-coil motif in most of the microbial surface proteins studied seems to be the formation of a stalk or rod-like structure, which projects other parts of the protein out from the surface to mediate better binding capacity (Phillips et al. 1981; Weis et al. 1988; Fischetti 1989). The oligomerization properties of the coiled-coil regions would assemble two or more binding domains in close proximity, presumably to increase avidity. In the monomeric coiled-coils proteins, this is accomplished by reiteration of the binding domains, which also seems to be the case for Vaa.

Materials and methods

Isolates, DNA, and plasmids

DNA from M. hominis isolates 4195 and 5941 was extracted using the method described by McClenaghan et al. (1984). M. hominis cells were grown in BEA medium (heart infusion broth [Difco], 2.2% (w/v); horse serum, 15% (w/v); fresh yeast extract, 1.9% (w/v); benzylpenicillin, 40 IU/mL; L-arginine, 0.23% (w/v); phenol red, 0.0023% (w/v), at pH 7.2), harvested at log phase and subsequently lysed on ice in a buffer containing 0.7% (w/v) N-laurylsarcocine, 10 μg RNase/mL (Sigma), 20 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, and 20 mM EDTA. Proteinase K (150 mg/mL) was added, and the cell lysate was incubated at 55°C for 2 h and 37°C for 1–2 h, followed by phenol, phenol/chloroform, and chloroform extractions (Sambrook et al. 1989). Both the E. coli strains Novablue and BL21 (DE3) and the pET30a vector used in this study were from Novagen. Plasmids from transformed E. coli were prepared by the method described by Sambrook et al. (1989). For sequencing, phenol/chloroform extraction was omitted.

PCR amplification

PCR was performed using the Expand High Fidelity PCR System from Roche according to the manufacturer's instructions. Oligonucleotide primers amplifying regions of the vaa gene of M. hominis 4195 encoding aa 27–353 (rVaa3), aa 27–105 (rVaaN), aa 86–226 (rVaaC), aa 132–226 (rVaaCδ), and the region of the vaa gene of M. hominis 5941 encoding aa 27–236 (rVaa5) corresponding to the mature full-length protein were used. The constructs are shown in Figure 1 ▶. The PCR products were purified using the Wizard PCR-Preps resin and Wizard Minicolumns (Promega). The production of rVaa3 was performed by Splicing by Overlap Extension (SOE) PCR (Horton et al. 1993). Overlapping primers, located in the triple-tryptophan cluster of the first cassette (aa 211–226) containing the UGA → UGG mutations, were used to generate two overlapping PCR products. The PCR products were purified, mixed, and used for extension, generating a full-length template for subsequent PCR with primers located at each end of the gene. As the second triple-tryptophan cluster (aa 328–343) was located only 30 bp from the stop codon, a long 3' primer containing the UGA → UGG mutations as well as the distal 30 bp was designed and used for PCR. The reverse primer used for production of rVaaC and rVaaCδ was fused to a sequence encoding the conserved 10 aa of the C-terminal sequence of all Vaa types. This created products similar to the C-terminal part (aa 86–236 and aa 132–236, respectively) of the category 5 Vaa type of M. hominis isolate 5941 (Boesen et al. 1998). The forward primer used for generation of rVaa5 and rVaa3 contained a sequence encoding the amino acid sequence LVPRGSNKGVNPDEM, containing a thrombin cleavage site and an epitope for the monoclonal antibody 35.2 (Birkelund et al. 1994). The epitope was used for identification of rVaa (data not shown). Furthermore, each end primer was fused to specific 14-bp ligation-independent cloning (LIC) sequences.

LIC-cloning

LIC-cloning was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Novagen). Wizard-purified PCR products containing the 14-bp LIC extensions in each end were used for LIC-cloning into the pET30a vector of Novagen and transformation into E. coli Novablue cells. Each construct was sequenced bidirectionally. Expression was performed in E. coli BL21 (DE3), with the resulting recombinant products called rVaa3 (corresponding to the full-length category 3 Vaa of M. hominis 4195), rVaa5 (corresponding to the full-length category 5 Vaa of M. hominis 5941), rVaaN (corresponding to the conserved N-terminal part of Vaa categories 3 and 5), and rVaaC and rVaaCδ (corresponding to C-terminal parts of Vaa category 5). All constructs contained an N-terminal LIC-tag (including a His-tag) encoded by the vector (Fig. 1 ▶).

Ni2+-affinity chromatography

E. coli BL21 (DE3) containing recombinant constructs were grown in a volume of 500 mL to 2 L of Luria-Bertani broth (Sambrook et al. 1989). The cells were induced at an OD600 of 0.6–0.8 with 1 mM IPTG and harvested after 3–4 h of induction at 37°C. The pellet was washed in PBS (20 mM sodium phosphate at pH 7.4, 250 mM NaCl) and stored at −70°C. The pellet was resuspended in ice-cold Binding buffer (500 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 20 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.0), and DNase I was added to a final concentration of 1 μg/mL.

The solution was applied to a French press for 3–5 cycles. The extract was then centrifuged in a 60-Ti rotor at 50,000 rpm for 30 min, and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.2-μm filter. The filtrate was applied to a 1- or 5-mL HiTrap Chelating column (Amersham Pharmacia) that had been charged in advance with NiCl2, washed in ultrafiltered water, and equilibrated in Binding buffer. The column was subsequently washed in Binding buffer followed by Wash buffer (500 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 20 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.0), and the recombinant protein was eluted from the column using Elution buffer (500 mM NaCl, 150 mM imidazole, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 20 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.0). The purification was performed at 4°C, and the absorbance at 280 nm was followed using a UV detector. All washing steps were performed until the absorbance reached the baseline. The LIC-tag of rVaa5 and rVaa3 was removed by thrombin (Amersham Pharmacia) cleavage, using ∼10 units of thrombin per mg of recombinant protein at 4°C for 72 h followed by addition of 0.5 μL benzamidine-coupled agarose (Sigma) per unit of thrombin. The solution was incubated on a shaker at 4°C for 30 min and centrifuged for 15 min at 15,000 rpm, and the supernatant was collected. This centrifugation step was repeated twice. Finally, the supernatant was applied to a Superdex 75 or 200 (Amersham Pharmacia) Prep Grade column (rVaa5 and rVaa3, respectively), and the pooled fractions of thrombin-cleaved rVaa5 or rVaa3 were concentrated using Centricon-30 (Amicon). The final tag-free products were called rVaa5Tand rVaa3T, respectively.

SDS-PAGE and native PAGE

The recombinant Vaa proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The samples were diluted in 2× SDS-sample buffer (125 mM Tris-HCl at pH 6.8, 20% [v/v] glycerol, 4.6% [w/v] SDS, 10% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.10% [w/v] bromophenol blue), boiled for 5 min, and separated by SDS-PAGE in 4%–20% gradient gels in SDS-PAGE Running buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.8, 192 mM glycine, 1% [w/v] SDS).

Samples for native PAGE were diluted in native loading buffer (50% [v/v] glycerol, 100 μg/mL bromophenol blue) and separated by native PAGE in 4%–20% gradient gels in native PAGE Running buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.8, 192 mM glycine). The gels were stained using Coomassie blue.

Circular dichroism

Protein samples were purified by gel filtration (Superdex 75 or 200 column) and dialyzed extensively against PBS supplemented with 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol. The concentrations of the final protein solutions were determined by amino acid analysis (performed by Charlotte Bisgaard Holm, The Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University, Copenhagen, Denmark). The CD measurements were performed in a Jasco J-710 spectropolarimeter flushed with N2 using cuvette sizes of 0.05, 0.02, and 0.01 cm, depending on protein concentration (measurements were performed by Karen Jørgensen at the Department of Chemistry, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark). α-Helix content was calculated from the ellipticity at 222 nm: fH = [Θ]222/(−33.000 deg cm2/dmole) (Padmanabhan et al. 1990). For the rVaaN:C and rVaaN:Cδ measurements, rVaaN and rVaaC or rVaaCδ were mixed in stoichiometric amounts.

Light scattering

Multiangle light-scattering measurements were performed with the miniDAWN laser light-scattering photometer (Wyatt Technology Corp.) coupled to the Shimadzu HPLC system with both UV and refractive index detectors. Gel filtration chromatography was performed on a TSK-gel G3000SW column (TOSOH Corp.) at 20°C. The ASTRA software was used for molecular mass calculations (Wyatt 1993). Protein concentration was estimated from the refractive index (RI) data and a dn/dc value of 0.187 mL/g. Dynamic light scattering was performed on a DynaPro 801 (Protein Solutions). Prior to light-scattering measurements the samples were filtered through a 0.02-μm filter (Whatman).

Computer analysis

Sequence analysis was performed using the Wisconsin Package Version 10.1 (Genetics Computer Group; Devereux et al. 1984). The program COILSCAN was used to find coiled-coil regions in Vaa. A window size of 28, 21, or 14 aa was used. The program was run both with and without the -WEI command for a weighted scan to ensure that the coiled-coil prediction was not a false positive result because of a highly charged amino acid sequence. The -TAB command was used to generate a table of the positions of the coiled-coil residues in the heptad repeat and their probability. The scan was performed using two weight matrices (mtidkcoils.dat and GenMoreData:mtkcoils.dat) to check for false positive predictions. The GAP and PILEUP programs were used for pairwise and multiple alignments, respectively (default settings). The Jpred2 server (http://jura.ebi.ac.uk:8888/) was used for prediction of secondary structure in the N-terminal and aligned cassette parts, respectively, using the Vaa sequences in the EMBL database.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Danish Health Research Council (Grant 12-1620-1), Aarhus University Foundation, Novo Foundation, Carlsberg Foundation, the Danish Biotechnological Research and Development Program, and a Ph.D. grant from the Faculty of Health Science, University of Aarhus, to T.B. M.K. was supported by a Hallas-Møller grant from the Novo Nordic Foundation. We thank Gregers R. Andersen for fruitful discussions and Ray Brown for critical reading of the manuscript. Furthermore, we wish to thank Inger Andersen, Karin Skovgaard, Karen Jørgensen, Charlotte B. Holm, and Birthe Bjerring Jensen for excellent technical assistance.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/ps.31901.

References

- Birkelund, S., Larsen, B., Holm, A., Lundemose, A.G., and Christiansen, G. 1994. Characterization of a linear epitope on Chlamydia trachomatis Serovar L2 DnaK-like protein. Infect. Immun. 62 2051–2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boesen, T., Emmersen, J., Jensen, L.T., Ladefoged, S.A., Thorsen, P., Birkelund, S., and Christiansen, G. 1998. The Mycoplasma hominis vaa gene displays a mosaic gene structure. Mol. Microbiol. 29 97–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhard, P., Kammerer, R.A., Steinmetz, M.O., Bourenkov, G.P., and Aebi, U. 2000. The coiled-coil trigger site of the rod domain of cortexillin I unveils a distinct network of interhelical and intrahelical salt bridges. Structure 8 223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor, C.R. and Schimmel, P.R. 1980. Biophysical chemistry part II: Techniques for the study of biological structure and function. W.H. Freeman, San Francisco.

- Cooper, T.M. and Woody, R.W. 1990. The effect of conformation on the CD of interacting helices: A theoretical study of tropomyosin. Biopolymers 30 657–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creighton, T.E. 1993. Proteins: Structures and molecular properties, 2nd ed. W.H. Freeman, New York.

- Cuff, J.A., Clamp, M., Siddiqui, A.S., Finlay, M., and Barton, G.J. 1998. Jpred: A consensus secondary structure prediction server. Bioinformatics 14 892–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devereux, J., Haerberli, P., and Smithies, O. 1984. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 12 387–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischetti, V.A. 1989. Streptococcal M protein: Molecular design and biological behaviour. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2 285–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, N.J. and Hitchcock-DeGregori, S. E. 1993. Conformational intermediates in the folding of a coiled-coil model peptide of the N-terminus of tropomyosin and α α-tropomyosin. Protein Sci. 2 1263–1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich, B., Feldmann, R.-C., and Hadding, U. 1993. Cytoadhesins of Mycoplasma hominis. Infect. Immun. 612945–2951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich, B., Kitzerow, A., Feldmann, R.-C., Schaal, H., and Hadding, U. 1996. Repetitive elements of the Mycoplasma hominis adhesin p50 can be differentiated by monoclonal antibodies. Infect. Immun. 64 4027–4034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich, B., Lang, K., Kitzerow, A., MacKenzie, C., and Hadding, U. 1998. Truncation as a novel form of variation of the p50 gene in Mycoplasma hominis. Microbiology 144 2979–2985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton, R.M., Ho, S.N., Pullen, J.K., Hunt, H.D., Cai, Z., and Pease, L.R. 1993. Gene splicing by overlap extension. Methods Enzymol. 217 270–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jedrzejas, M.J., Hollingshead, S.K., Lebowitz, J., Chantalat, L., Briles, D.E., and Lamani, E. 2000. Production and characterization of the functional fragment of Pneumococcal surface protein A. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 373 116–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzerow, A., Henrich, B., and Hadding, U. 1994. The cytadhesin p50 from Mycoplasma hominis: Expression and analysis of recombinant peptides in host recognition. IOM Lett. 3182–183. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzerow, A., Hadding, U., and Henrich, B. 1999. Cyto-adherence studies of the adhesin p50 of Mycoplasma hominis. J. Med. Microbiol. 48485–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladefoged, S. 2000. Molecular dissection of Mycoplasma hominis. APMIS Suppl. 2000 108 1–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupas, A. 1996. Coiled coils: New structures and new functions. Trends. Biochem. Sci. 21 375– 382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClenaghan, M., Herring, A.J., and Aitken, I.D. 1984. Comparison of Chlamydia psittaci isolates by DNA restriction endonuclease analysis. Infect. Immun. 45 384–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomizu, M., Utani, A., Beck, K., Otaka, A., Roller, P.P., and Yamada, Y. 1996. Mechanism of laminin chain assembly. Biochemistry 35 2885–2893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan, S., Marqusee, S., Ridgeway, T., Laue, T.M., and Baldwin, R.L. 1990. Relative helix-forming tendencies of nonpolar amino acids. Nature 344 268–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, G.N., Jr., Flicker, P.F., Cohen, C., Manjula, B.N., and Fischetti, V.A. 1981. Streptococcal M protein: α-Helical coiled-coil structure and arrangement on the cell surface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 78 4689–4693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razin, S., Yogev, D., and Naot, Y. 1998. Molecular biology and pathogenicity of mycoplasmas. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62 1094–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J., Fritsch, E.F., and Maniatis, T. 1989. Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Steinmetz, M.O., Stock, A., Schulthess, T., Landwehr, R., Lustig, A., Faix, J., Gerish, G., Aebi, U., and Kammerer, R.A. 1998. A distinct 14 residue site triggers coiled-coil formation in cortexillin I. EMBO J. 17 1883–1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanford, C. 1961. Physical chemistry of macromolecules. John Wiley, New York.

- Tashiro, M., Tejero, R., Zimmerman, D.E., Celda, B., and Montelione, G.T. 1997. High-resolution solution NMR structure of the Z domain of staphylococcal protein A. J. Mol. Biol. 272 573–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis, W., Brown, J.H., Cusack, S., Paulson, J.C., Skehel, J.J., and Wiley, D.C. 1988. Structure of the influenza hemagglutinin complexed with its receptor, sialic acid. Nature 333 426–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt, P.J. 1993. Light scattering and the absolute characterization of macromolecules. Anal. Chim. Acta 272 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q. and Wise, K.S. 1996. Molecular basis of size and antigenic variation of a Mycoplasma hominis adhesin encoded by divergent vaa genes. Infect. Immun. 64 2737–2744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1997. Localized reversible frameshift mutation in an adhesin gene confers a phase-variable adherence phenotype in mycoplasma. Mol. Microbiol. 25 859–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]