Abstract

The HypF N-terminal domain has been found to convert readily from its native globular conformation into protein aggregates with the characteristics of amyloid fibrils associated with a variety of human diseases. This conversion was achieved by incubation at acidic pH or in the presence of moderate concentrations of trifluoroethanol. Electron microscopy showed that the fibrils grown in the presence of trifluoroethanol were predominantly 3–5 nm and 7–9 nm in width, whereas fibrils of 7–9 nm and 12–20 nm in width prevailed in samples incubated at acidic pH. These results indicate that the assembly of protofilaments or narrow fibrils into mature amyloid fibrils is guided by interactions between hydrophobic residues that may remain exposed on the surface of individual protofilaments. Therefore, formation and isolation of individual protofilaments appears facilitated under conditions that favor the destabilization of hydrophobic interactions, such as in the presence of trifluoroethanol.

Keywords: Aggregation, amyloid fibrils, HypF N-terminal domain, protofilaments, trifluoroethanol

A number of human diseases, including Alzheimer's disease and the spongiform encephalopathies, are associated with the formation of stable protein aggregates known as amyloid fibrils. In each of these pathological states, a specific protein or protein fragment changes from its native soluble form into insoluble aggregates which subsequently develop slowly into fibrils accumulating in a variety of organs and tissues (Kelly 1998; Dobson 1999; Bellotti et al. 1999; Rochet and Lansbury, 2000). This phenomenon frequently has serious consequences and usually leads to premature death. Despite the variation encountered in the amino acid sequences and native structures of proteins associated with these diseases, the amyloid fibrils from different pathologies display common structural features. They typically appear to be formed from 2–6 unbranched protofilaments 2–5 nm wide that associate laterally or twist together to form fibrils with a 4–13 nm width (Shirahama and Cohen 1967; Merz et al. 1983; Serpell et al. 1995, 2000). Formation of fibrils with such morphology has also been observed widely in vitro from the proteins associated with disease (Shirahama et al. 1973; Glenner et al. 1971; Goldsbury et al. 1997; Harper et al. 1997; Conway et al. 1998).

Recently, it has been found that proteins other than those associated with diseases are capable of forming amyloid fibrils under appropriate conditions in vitro (Guijarro et al. 1998; Litvinovich et al. 1998; Chiti et al. 1999; Konno et al. 1999; Krebs et al. 2000; Ramirez-Alvarado et al. 2000; Villegas et al. 2000; Yutani et al. 2000; Fandrich et al. 2001; Pertinhez et al. 2001). It has been proposed that amyloid fibril formation can occur when the native globular fold of a protein is destabilized under conditions in which non-covalent interactions still remain favourable (Chiti et al. 1999). The ability for rational design of conditions promoting amyloid formation has implications for understanding the origin of amyloid formation in vivo because the latter can no longer be assumed to arise from the unique physical properties of a limited number of protein sequences (Chiti et al. 1999; Dobson 1999; Rochet and Lansbury 2000). In addition, the possibility of producing amyloid fibrils under controlled conditions provides us with the opportunity to investigate the molecular basis of amyloid formation using a wide range of proteins.

In this work, we investigate the conditions favorable for amyloid fibril formation using the N-terminal domain of HypF, a newly cloned globular protein factor participating in the maturation of the prokaryotic [NiFe] hydrogenase that is involved in hydrogen metabolism (Friedrich and Schwartz 1993). In addition to showing that this domain is capable of forming in vitro amyloid fibrils of the type associated with diseases, we will describe how solution conditions can be designed to promote selective formation of either the mature fibrils typical of pathological states or their constituents, the protofilaments that normally associate laterally or twist together to form the mature fibrils.

Results

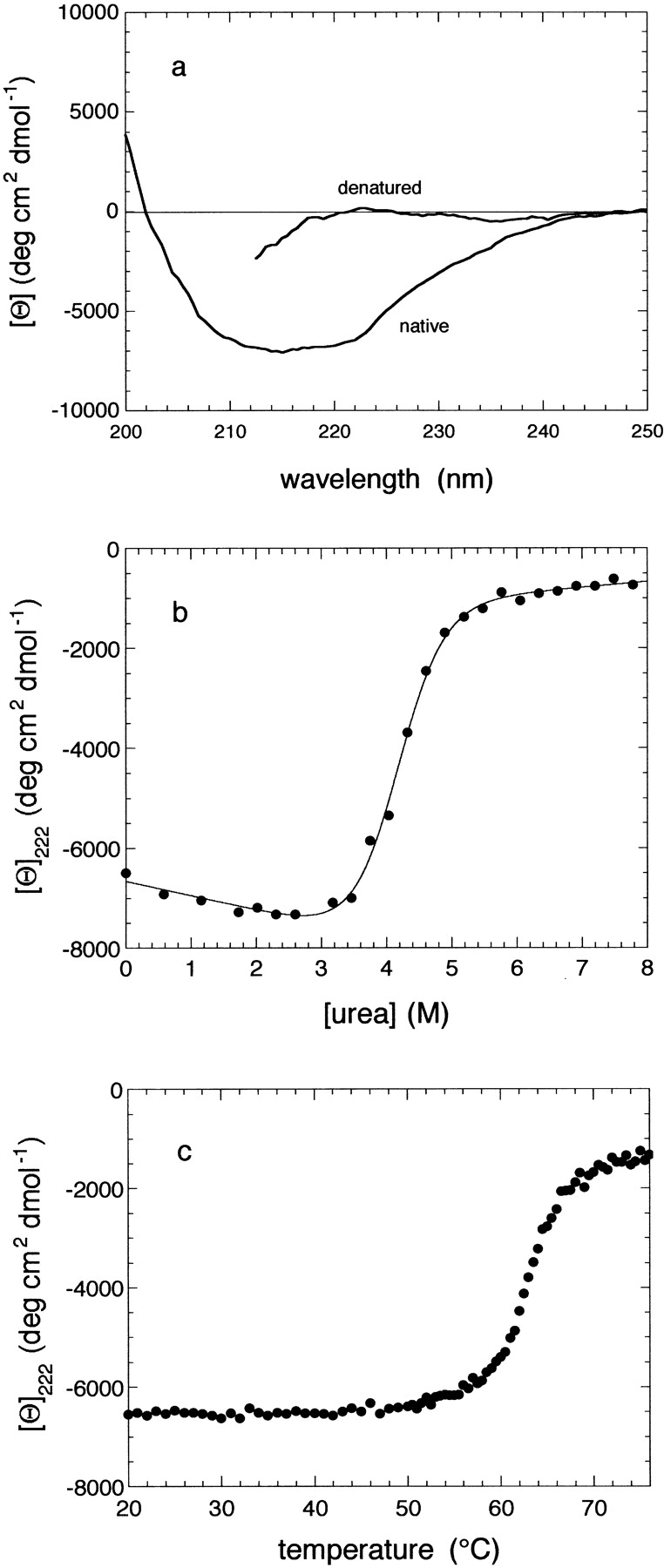

Figure 1A ▶ shows the far-UV circular dichroism (CD) spectra of the purified HypF N-terminal domain acquired in the presence and absence of 5 M GdnHCl (guanidine hydrochloride). Unlike the CD spectrum acquired in the presence of GdnHCl, the spectrum of the protein acquired under native conditions is consistent with a well-structured protein with an α/β topology. Figures 1B,C ▶ show the change of mean residue ellipticity at 222 nm on the increase of urea concentration and temperature, respectively. The urea and heat-denaturation curves reveal single sharp transitions, indicating that this protein fragment has a globular and well-defined three-dimensional structure under native conditions. The analysis of the urea denaturation curve yielded values of 29±3 kJ/mol, 7±1 kJ/mol per mole, and 4.2±0.2 for the ΔG(H2O), m, and Cm values, respectively. Unlike the urea-denatured protein, the heat-denatured domain was not capable of recovering native-like ellipticity when cooled to room temperature, indicating that the thermal denaturation process is irreversible. Therefore, determination of the thermodynamic parameters characterising the unfolding thermal reaction was not attempted.

Fig. 1.

(A) CD spectra of native and GdnHCl-denatured HypF N-terminal domain. (B) Change of the 222 nm mean residue ellipticity on addition of urea. (C) Change of the 222 nm mean residue ellipticity following increases in temperature.

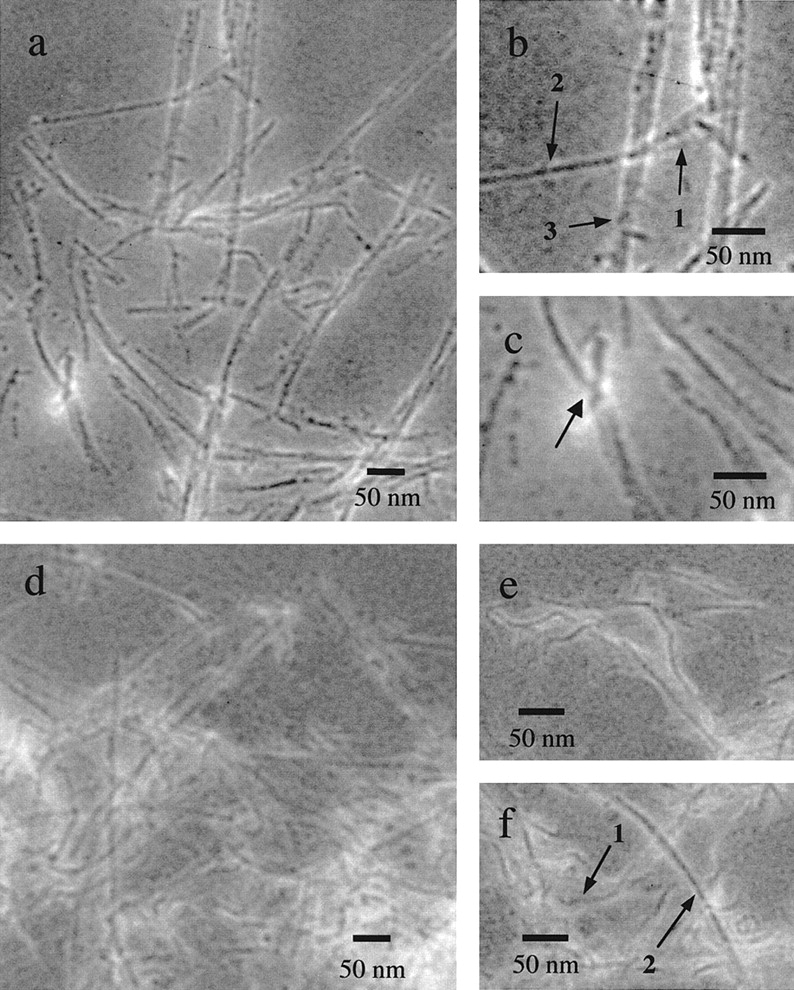

To induce formation of amyloid fibrils, the HypF N-terminal domain was incubated under different solution conditions including (i) 20 mM citrate buffer (pH 3.0), (ii) 50 mM acetate buffer and 15–40% (v/v) trifluoroethanol (TFE) at pH 5.5, and (iii) 50 mM acetate buffer (pH 5.5) at a temperature of 50°C, which was chosen as the highest temperature at which the protein is completely native. Protein samples incubated under non-denaturing conditions were also prepared as controls. The samples, containing the protein at concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 0.8 mg/ml, were left at room temperature (except those incubated at 50°C) for 1–4 weeks. Electron micrographs acquired from samples incubated at pH 3 reveal the presence of many fibrils (Fig. 2A–C ▶). Analysis of ∼100 fibrils from three different specimens identified three different types of fibrils, each displaying a characteristic width: 3–5 nm, 7–9 nm, and 12–20 nm. Figure 2B ▶ shows an area of a specimen in which the three different types are all present (numbered 1, 2, and 3, respectively). An 8 nm fibril shown in the figure ▶ (numbered 2) appears to dissociate at its terminus into its constituents, allowing a 4 nm fibril to be observed (numbered 1). Fig. 2C ▶ shows another detail in which two fibrils of ca. 8 nm appear to associate and twist together to form a larger fibril. In other cases, pairs of 8 nm fibrils seem to associate in a parallel manner forming 15–20 nm ribbon-like fibrils (Fig. 2A–B ▶). Although the finer structure of the three types of fibrils is not visible from these micrographs, these pictures indicate that the fibrils with 12–20 nm widths originate from the association of pairs of fibrils of 7–9 nm in width which, in turn, result from the assembly of two or more fibrils 3–5 nm in width. The latter are extremely rare in the samples incubated at low pH values and are visible only at the ends of some of the fibrils with diameters of 7–9 nm when these appear to dissociate into their constituents. Many studies have regarded fibrils of 2–5 nm in width as protofilaments, (i.e., the basic units that assemble to form larger fibrils; Glenner et al. 1971; Merz et al. 1983; Serpell et al. 1995; Goldsbury et al. 1997; Harper et al. 1997; Conway et al. 1998; Serpell et al. 2000). Hence, it is likely that the narrowest fibrils observed here represent the protofilaments that associate to form the larger fibrils. However, one cannot rule out that the 3–5 nm fibrils also originate from the association of narrower filaments.

Fig. 2.

Electron micrographs of amyloid fibrils formed from the N-terminal domain of HypF. Fibrils were grown for one month at room temperature by incubating the domain, at a concentration of 0.3 mg/mL, in 20 mM citrate buffer (pH 3.0) (A–C) and in 50 mM acetate buffer (pH 5.5) in the presence of 30% (v/v) TFE (D–F). The numbers in (B) and (F) indicate fibrils with diameters of 3–5 nm (1), 7–9 nm (2) and 12–20 nm (3). The pictures obtained from samples incubated at low pH (A–C) show that the 7–9 and 12–20 nm fibrils are abundant, whereas the 3–5 nm fibrils are rare. By contrast, the 3–5 nm and 7–9 nm fibrils are highly populated in samples containing TFE (D–F), whereas those with larger widths are virtually absent.

Fibrils of the type observed in samples incubated at pH 3 were also visible in samples incubated in the presence of TFE (Fig. 2D–F ▶), but with a different size distribution. The 3–5 nm and 7–9 nm wide fibrils are both abundant, whereas the largest ones (12–20 nm) appear to be completely absent altogether. Figures 2D,E show regions of specimens revealing many examples of fibrils with diameters of 3–5 and 7–9 nm, respectively. Figure 2F ▶ shows another region in which both types of fibrils are present (numbered 1 and 2). Unlike the situation in the samples incubated at low pH, the narrowest fibrils grown in the presence of TFE are abundant and appear fully dissociated from the fibrils with larger widths. Some of these are short and curved, resembling the fibrillar aggregates called protofibrils observed for other protein systems (Harper et al. 1997). In contrast, others are long and rigid resembling more closely the fibril constituents (i.e., protofilaments). Interestingly, a size distribution of this type was also obtained when TFE was added to fibrils grown at pH 3.

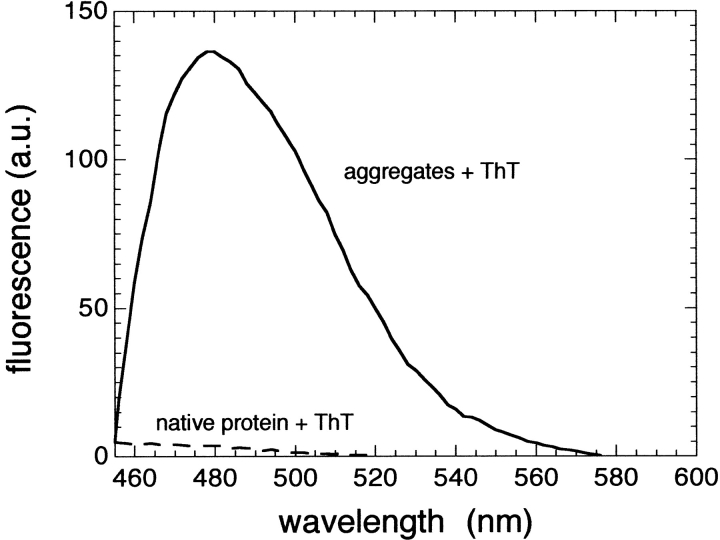

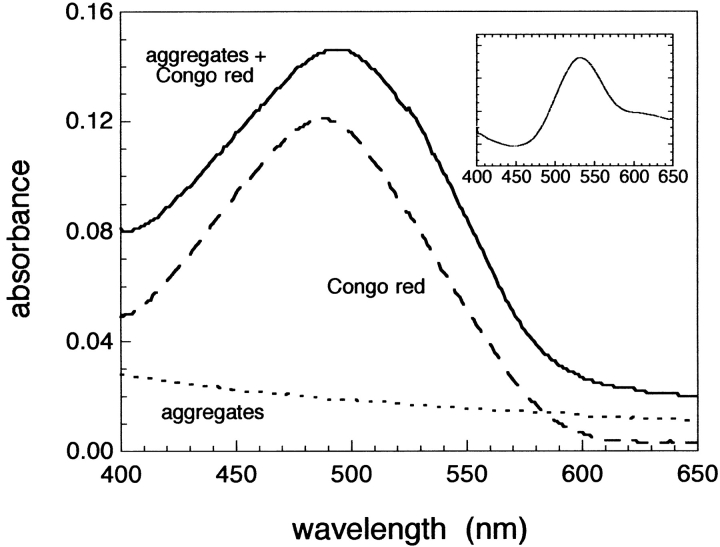

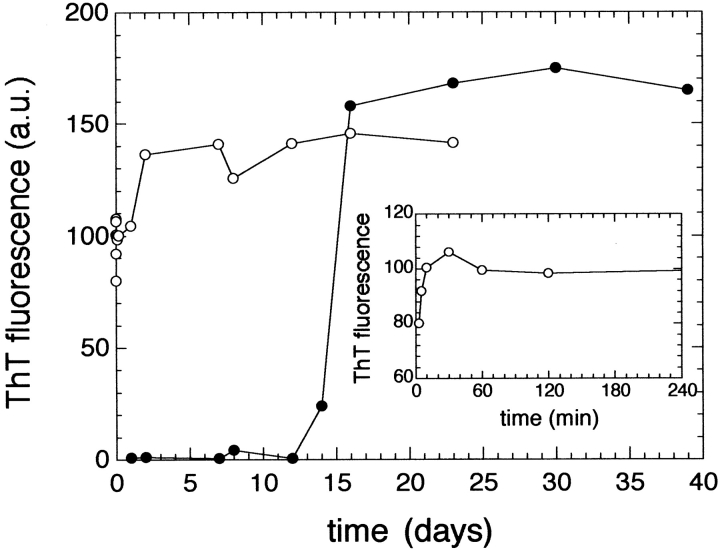

The aggregates of the HypF N-terminal domain formed in the presence of TFE were analysed further with two colorimetric assays specific for amyloid fibrils. Samples incubated for one month in the presence of moderate concentrations of TFE cause the enhancement of fluorescence of Thioflavine T (ThT). This enhancement is more than 30 times higher than that observed on addition of a protein sample incubated in the absence of TFE (Fig. 3 ▶). The absorption peak of Congo red also undergoes a red-shift when aliquots of the protein solutions incubated under these conditions are added to the dye (Fig. 4 ▶). An increase of the absorbance values throughout the whole range of wavelength investigated here is also observed when the protein aggregates are added to the dye. This increase clearly originates from the light scattering by the protein aggregates; indeed, the spectrum of the aggregated protein in the absence of Congo red yields absorbance values higher than zero (Fig. 4 ▶, dotted line). Subtraction from the experimentally measured spectrum of the aggregates in the presence of Congo red of spectra of the aggregates alone and Congo red alone yields a difference spectrum with a maximum at 530–540 nm (Fig. 4 ▶, inset). Such a result is expected only if ordered amyloid-like aggregates are present in the solution (Klunk et al. 1989). Figure 5 ▶ shows the time-course of the change of ThT fluorescence as the protein aggregates form at pH 3 or in the presence of TFE. Whereas at acidic pH the aggregates develop after a lag phase of several days, in the presence of TFE the maximum ThT fluorescence is reached after a few minutes (Fig. 5 ▶, inset). The observed kinetics indicate that the prevalence of fibrils with larger diameters in the samples incubated at low pH cannot be attributed to a more rapid rate of the fibril formation process.

Fig. 3.

Increase of ThT fluorescence on binding to the fibrils of the HypF N-terminal domain. The spectrum obtained after incubating the native protein in the absence of TFE as a control is also shown (dashed line). Both spectra were obtained by subtracting from the experimentally measured spectra the spectrum of ThT recorded in the absence of protein.

Fig. 4.

Shift of the Congo red absorption peak on addition of fibrils formed from the HypF N-terminal domain. The spectra are those of Congo red without protein (dashed line), aggregated protein without Congo red (dotted line) and Congo red with aggregated protein (solid line). The spectrum of Congo red and protein pre-incubated under native conditions overlaps substantially with that recorded in the presence of Congo red alone and is not shown in the figure for clarity. The spectrum (inset) was obtained by subtracting the spectrum of Congo red alone and that of aggregated protein alone from the experimentally measured spectrum in the presence of Congo red and aggregated protein. This allowed the spectrum of aggregate-bound Congo red to be obtained.

Fig. 5.

Time course of aggregate growth followed by ThT fluorescence at acidic pH (filled circles) and in the presence of TFE (empty circles). (Inset) The observed kinetics within the first 4 h.

The samples incubated at high temperatures show the presence of visible protein aggregates that increase considerably the fluorescence of ThT. However, such a ThT fluorescence enhancement was observed only at protein concentrations >0.3 mg ml−1 and was about one third of that observed at low pH or in the presence of TFE. Moreover, these aggregates do not have a fibrillar appearance under electron microscopy, appearing as large protein aggregates devoid of any geometric form. Nor do they cause the characteristic red shift of the Congo red dye. Therefore, the aggregated material observed under these conditions was not investigated in any further detail. The ability of the amorphous aggregates to bind to ThT indicates that ThT binding is not completely specific for amyloid fibrils as found for Congo red (Khurana et al. 2001) We do not exclude, however, the possibility that fibril formation can occur at temperatures >50°C or at this temperature value under different conditions of pH or ionic strength. The samples used as negative controls and containing the N-terminal domain of HypF in acetate buffer (pH 5.5) did not show the presence of any aggregates under electron microscopy, nor did they modify the fluorescence spectrum of ThT or the absorption spectrum of Congo red.

Discussion

As with other protein systems investigated so far (Guijarro et al. 1998; Litvinovich et al. 1998; Chiti et al. 1999; Konno et al. 1999; Goda et al. 2000; Krebs et al. 2000; Ramirez-Alvarado et al. 2000; Villegas et al. 2000; Yutani et al. 2000; Fandrich et al. 2001; Pertinhez et al. 2001), amyloid formation by the HypF N-terminal domain in vitro was achieved by destabilizing the native state of the protein under conditions in which non-covalent interactions still remain favorable. This indicates that solution conditions promoting the formation in vitro of amyloid fibrils can be designed rationally and support the hypothesis that the ability to form amyloid fibrils is a property of many, if not all, polypeptide chains (Chiti et al. 1999).

Furthermore, using the HypF N-terminal domain we have shown that it is possible to select solution conditions to promote formation of either amyloid fibrils or their constituent protofilaments. Moderate concentrations of TFE destabilize the interactions promoting the assembly of protofilaments formed from this protein domain. It was reported previously that long-term incubation of acylphosphatase in the presence of moderate concentrations of TFE also generates relatively long protofilaments that remain dissociated for periods longer than those observed for other fibril formation processes (Chiti et al. 1999). Furthermore, addition of TFE to fibrils obtained from the peptide corresponding to the 10–19 region of the transthyretin sequence disrupts the rigid fibrils to reveal the constituent protofilaments (MacPhee and Dobson 2000). A peptide corresponding to the 34–42 region of the sequence of the Aβ fragment associated with Alzheimer's disease generates protofilaments, rather than complete fibrils, when the hydrophobic residues that are thought to be exposed on the surface of the protofilament are replaced with hydrophilic ones (Lazo and Downing 1999). Finally, protofilaments are also more stable when the L55P mutant of transthyretin undergoes aggregation (Lashuel et al. 1999).

All these findings, in addition to the results reported here with the HypF N-terminal domain, indicate that protofilament association into larger fibrils is likely to be guided, at least in part, by interactions between the side chains of hydrophobic residues that remain solvent-exposed on the surface of individual protofilaments and that mild destabilization of such interactions makes it possible to form and isolate the individual protofilaments. The ability of TFE to stabilize mainchain hydrogen bonds within individual protofilaments may also contribute to the relative stability of these structures in solutions containing TFE, as β-sheet structure is probably an important force driving the assembly of individual protein or peptide molecules into protofilaments. Protofilaments can grow and be stable independently of any further supramolecular organization. Solutions containing moderate concentrations of TFE are very favorable for the stabilization of individual protofilaments as TFE is known to weaken hydrophobic interactions without disrupting the backbone hydrogen bonds within individual protofilaments. Although we cannot make the generalization that TFE leads universally to protofilament formation (as opposed to other partially denaturing conditions such as low pH, high temperatures, and destabilizing mutations), we propose that dissociation of fibrils into their constituent protofilaments requires conditions destabilizing hydrophobic interactions that might exist at the interface between interacting protofilaments.

The ability for rational design of suitable solvent conditions for the formation of individual protofilaments has implications for the investigation of the structure and the mechanism of formation of amyloid fibrils. The possibility of preparing isolated protofilaments to order will allow structural investigations to be carried out on materials with a lower degree of complexity than mature fibrils. It will also facilitate the biophysical investigation of the steps associated with aggregation as protofilament formation is likely to be a less complex process than full fibril formation. More importantly, experimental procedures directed to the formation of protein aggregates and fibrils of various types will help in the identification of the aggregate species responsible for cell damage.

Materials and methods

Cloning, expression, and purification

The genomic DNA for the HypF N-terminal domain was isolated from Escherichia coli DH5α cells by Genomic PrepTM (Pharmacia). The DNA fragment corresponding to residues 993–1263 of the whole hypf gene was amplified by PCR using suitable primers containing the restriction sites for BamHI and EcoRI, respectively. Samples (1.0 μM) of each primer were added to 100 ng of template DNA, 10X PCR buffer, 200 μM dNTPs, and 2.5 units of Taq DNA polymerase (Finnzymes) in a volume of 50 μL. The fragments resulting from PCR amplification (94°C for 15 s, 52°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min, 25 cycles) were digested with BamHI and EcoRI, ligated into pGEX-2T downstream and in frame with glutathione S-transferase, and sequenced in their entirety. Expression of protein in the E. coli DH5α cells and its subsequent purification were carried out as described previously for muscle acylphosphatase (Modesti et al. 1995). Protein purity and quality were checked by SDS-PAGE, ES-MS, and amino acid analysis. The resulting sequence of the domain is AKNTSCGVQLRIRGKVQGVGFR PFVWQLAQQLNLHGDVCNDGDGVEVRLREDPETFLVQLY QHCPPLARIDSVEREPFIWSQLPTEFTIR. A Gly-Ser dipeptide is also present at the N terminus as a result of the cloning in pGEX-2T.

Circular dichroism

Far-UV CD spectra were acquired using a Jasco J-720 spectropolarimeter with a thermostat (Great Dunmow, Essex, UK). The CD spectra were recorded at a protein concentration of 0.2 mg mL−1 in 50 mM acetate buffer (pH 5.5), 25°C. To acquire the CD spectrum of the domain under denaturing conditions, guanidinium chloride was added to a final concentration of 5.5 M.

Equilibrium urea- and heat-denaturation

25 samples containing 0.2 mg/mL protein in 50 mM acetate buffer (pH 5.5) were equilibrated at 25°C in the presence of different concentrations of urea ranging from 0 to 8 M. The mean residue ellipticity at 222 nm was plotted versus urea concentration and the resulting curve analyzed using the method described by Santoro and Bolen (1988). For acquiring a heat-denaturation curve, a 0.2 mg/mL solution of the N-terminal HypF domain, incubated in acetate buffer (pH 5.5), was placed in the CD cell holder and the temperature increased slowly at a rate of 0.5°C/min. A thermocouple was used to monitor the temperature inside the cuvette and the CD signal at 222 nm was acquired at 1.0°C intervals from 20° to 76°C.

Electron microscopy

Electron micrographs were acquired using a JEM 1010 transmission electron microscope at 80 kV excitation voltage. In each case, a 3 μL sample of protein solution was placed on a formvar- and carbon-coated grid. The sample was then negatively stained with 30 μL of 2% uranyl acetate and observed at a magnification of 12–30,000×. Morphological investigation and size determination of the fibrils were performed by analysing ∼30–40 fibrils per specimen and 3 specimens for each experimental condition (to achieve a total number of ∼100 fibrils for each experimental condition).

Thioflavine T assay

The protein domain was incubated for either one week or one month at a concentration of 0.8 mg/mL in 50 mM acetate buffer, 30% (v/v) TFE (pH 5.5) at room temperature. An aliquot of this sample and an aliquot of a highly concentrated solution of ThT were added to a solution of 25 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.0). Final conditions after mixing were 0.03 mg/mL protein, 25 μM ThT, and 25 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) at 25°C. The fluorescence spectra were acquired immediately after mixing using a Shimadzu RF-5000 spectrofluorimeter and excitation and emission wavelengths of 440 and 485 nm, respectively. For the kinetic experiments, the protein domain was incubated at 0.4 mg/mL at room temperature in 30% (v/v) TFE, 50 mM acetate buffer (pH 5.5) or in 20 mM citric acid (pH 3). At regular time intervals, aliquots of the protein samples were withdrawn to perform the ThT assay as described above.

Congo red assay

The protein was incubated for either one week or one month at a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL in 50 mM acetate buffer, 30% (v/v) TFE (pH 5.5). 133 μL of this sample were mixed with 867 μL of a solution containing 20 μM Congo red, 10 mM phosphate buffer, 150 mM NaCl (pH 7.4). Mixtures without protein and mixtures without Congo red were also prepared as controls. The absorption spectra were acquired after 2–3 min equilibration using an Ultrospec 2000 spectrophotometer (Pharmacia Biotech).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funds from the Fondazione Telethon-Italia (F.C.), the Wellcome Trust (C.M.D.), the Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (contribute n. 99.02609.04) and the Ministero dell'Università e della Ricerca Scientifica e Tecnologica (PRIN funds "Folding e misfolding di proteine"). The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/ps.10201.

References

- Bellotti, V., Mangione, P., and Stoppini, M. 1999. Biological activity and pathological implications of misfolded proteins. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 55 977–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiti, F., Webster, P., Taddei, N., Clark, A., Stefani, M., Ramponi, G., and Dobson, C.M. 1999. Designing conditions for in vitro formation of amyloid protofilaments and fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96 3590–3594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway, K.A., Harper, J.D., and Lansbury, P.T. 1998. Accelerated in vitro fibril formation by a mutant α-synuclein linked to early-onset Parkinson disease. Nature Med. 11 1318–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson, C.M. 1999. Protein misfolding, evolution, and disease. Trends Biochem. Sci. 9 329–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fandrich, M., Fletcher, M.A., and Dobson, C.M. 2001. Amyloid fibrils from muscle myoglobin. Nature 410 165–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich, B. and Schwartz, E. 1993. Molecular biology of hydrogen utilization in aerobic chemolithotrophs. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 47 351–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenner, G.G., Ein, D., Eanes, E.D., Bladen, H.A, Terry, W., and Page, D.L. 1971. Creation of "amyloid" fibrils from Bence Jones Proteins in vitro. Science 174 712–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goda, S., Takano, K., Yamagata, Y., Nagata, R., Akutsu, H., Maki, S., Namba, K., and Yutani, K. 2000. Amyloid protofilament formation of hen egg lysozyme in highly concentrated ethanol solution. Protein Sci. 9 369–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsbury, C.S., Cooper, G.J.S., Goldie, K.N., Muller, S.A., Saafi, E.L., Gruijters, W.T.M., Misur, M.P., Engel, A., Aebi, U., and Kistler, J. 1997. Polymorphic fibrillar assembly of human amylin. J. Struct. Biol. 119 17–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guijarro, J.I., Sunde, M., Jones, J.A., Campbell, I.D., and Dobson, C.M. 1998. Amyloid fibril formation by an SH3 domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95 4224–4228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper, J.D., Lieber, C.M., and Lansbury, P.T. 1997. Atomic force microscopic imaging of seeded fibril formation and fibril branching by the Alzheimer's disease amyloid-β protein. Chem. Biol. 4 951–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, J.W. 1998. The alternative conformations of amyloidogenic proteins and their multi-step assembly pathways. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 8 101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurana, R., Uversky, V.N., Nielsen, L., and Fink, A.L. 2001. Is Congo red an amyloid-specific dye? J. Biol. Chem. 276 22715–22721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klunk, W.E., Pettegrew, J.W., and Abraham, D.J. 1989. Quantitative evaluation of congo red binding to amyloid-like proteins with a beta-pleated sheet conformation. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 37 1273–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konno, T., Murata, K., and Nagayama, K. 1999. Amyloid-like aggregates of a plant protein: A case of a sweet-tasting protein, monellin. FEBS Lett. 454 122–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs, M.R., Wilkins, D.K., Chung, E.W., Pitkeathly, M.C., Chamberlain, A.K., Zurdo, J., Robinson, C.V., and Dobson, C.M. 2000. Formation and seeding of amyloid fibrils from wild-type hen lysozyme and a peptide fragment from the beta-domain. J. Mol. Biol. 300 541–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashuel, H.A., Wurth, C., Woo, L., and Kelly, J.W. 1999. The most pathogenic transthyretin variant, L55P, forms amyloid fibrils under acidic conditions and protofilaments under physiological conditions. Biochemistry 38 13560–13573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazo, N.D. and Downing, D.T. 1999. Fibril formation by amyloid-beta proteins may involve beta-helical protofibrils. J. Pept. Res. 53 633–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litvinovich, S.V., Brew, S.A., Aota, S., Akiyama, S.K., Haudenschild, C., and Ingham, K.C. 1998. Formation of amyloid-like fibrils by self-association of a partially unfolded fibronectin type III module. J. Mol. Biol. 280 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPhee, C.E. and Dobson, C.M. 2000. Chemical dissection and reassembly of amyloid fibrils formed by a peptide fragment of transthyretin. J. Mol. Biol. 297 1203–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merz, P.A., Wisniewski, H.M., Somerville, R.A., Bobin, S.A., Masters, C.L., and Iqbal, K. 1983. Ultrastructural morphology of amyloid fibrils from neuritic and amyloid plaques. Acta Neuropathol. 60 113–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modesti, A., Taddei, N., Bucciantini, M., Stefani, M., Colombini, B., Raugei, G., and Ramponi, G. 1995. Expression, purification, and characterization of acylphosphatase muscular isoenzyme as fusion protein with glutathione S-transferase. Protein Expr. Purif. 6 799–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertinhez, T.A., Bouchard, M., Tomlinson, E.J., Wain, R., Ferguson, S.J., Dobson, C.M., and Smith, L.J. 2001. Amyloid fibril formation by a helical cytochrome. FEBS Lett. 495 184–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Alvarado, M., Merkel, J.S., and Regan, L. 2000. A systematic exploration of the influence of the protein stability on amyloid fibril formation in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97 8979–8984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochet, J.C. and Lansbury, P.T. 2000. Amyloid fibrillogenesis: Themes and variations. Curr. Op. Struct. Biol. 10 60–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro, M.M. and Bolen, D.W. 1988. Unfolding free-energy changes determined by the linear extrapolation method. 1. Unfolding of phenylmethanesulfonyl alpha-chymotrypsin using different denaturants. Biochemistry 27 8063–8068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serpell, L.C., Sunde, M., Fraser, P.E., Luther, P.K., Morris, E.P., Sangren, O., Lundgren, E., and Blake, C.C.F. 1995. Examination of the structure of the transthyretin amyloid fibril by image reconstruction from electron micrographs. J. Mol. Biol. 254 113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serpell, L.C., Sunde, M., Benson, M.D., Tennent, G.A., Pepys, M.B., and Fraser, P.E. 2000. The protofilament substructure of amyloid fibrils. J. Mol. Biol. 300 1033–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirahama, T. and Cohen, A.S. 1967. High-resolution electron microscopic analysis of the amyloid fibril. J. Cell. Biol. 33 679–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirahama, T., Benson, M.D., Cohen, A.S., and Tanaka, A. 1973. Fibrillar assemblage of variable segments of immunoglobulin light chains: an electron microscopic study. J. Immunol. 110 21–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villegas, V., Zurdo, J., Filimonov, V.V., Avilés, F.X, Dobson, C.M., and Serrano, L. 2000. Protein engineering as a strategy to avoid formation of amyloid fibrils. Protein Sci. 9 1700–1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yutani, K., Takayama, G., Goda, S., Yamagata, Y., Maki, S., Namba, K., Tsunasawa, S., and Ogasahara, K. 2000. The process of amyloid-like fibril formation by methionine aminopeptidase from a hyperthermophile, Pyrococcus furiosus. Biochemistry 39 2769–2777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]