Abstract

CaVP is a calcium-binding protein from amphioxus. It has a modular composition with two domains, but only the two EF-hand motifs localized in the C-terminal domain are functional. We recently determined the solution structure of this regulatory half (C-CaVP) in the Ca2+-saturated form and characterized the stepwise ion binding. This paper reports the 15N nuclear relaxation rates of the Ca2+-saturated C-CaVP, measured at four different NMR fields (9.39, 11.74, 14.1, and 18.7 T), which were used to map the spectral density function for the majority of the amide HN-N vectors. Fitting the spectral density values at eight frequencies by a model-free approach, we obtained the microdynamic parameters characterizing the global and internal movements of the polypeptide backbone. The two EF-hand motifs, including the ion binding loops, behave like compact structural units with restricted mobility as reflected in the quite uniform order parameter and short internal correlation time (< 20 nsec). Comparative analysis of the two Ca2+ binding sites shows that site III, having a larger affinity for the metal ion, is generally more rigid, and the amide vector in the second residue of each loop is significantly less restricted. The linker fragment is animated simultaneously by a larger amplitude fast motion and a slow conformational exchange on a microsecond to millisecond time scale. The backbone dynamics of C-CaVP characterized here is discussed in relation with other well-characterized Ca2+-binding proteins.

Supplemental material: See www.proteinscience.org

Keywords: Protein dynamics, Ca2+-binding proteins, NMR, 15N relaxation

Calcium ion, as a second messenger, is involved in many biological processes such as muscle contraction, secretion, or gene transcription (Berridge et al. 1998). Intracellular calcium signaling, uptake, transport, and regulation of its concentration depend on a class of proteins called calcium binding proteins (CaBP) or EF-hand proteins. They may be divided generally into two major classes: (1) the buffers (calbindin D9k, parvalbumin, sarcoplasmic Ca2+-binding proteins), high affinity proteins involved in control of cellular Ca2+ concentration, and (2) the sensor proteins (calmodulin, troponin C), which translate the transitory increase of ion concentration in a target activation. The 12-residue calcium-binding loops have a highly conserved sequence, especially at positions providing an oxygen ligand to the ion (Falke et al. 1994). The structure of this fragment, in the calcium-bound form, is well organized and stabilized by several hydrogen bonds (Herzberg and James 1985).

Calcium vector protein (CaVP), a Ca2+ sensor molecule constituted of 161 residues, was identified in large quantities in amphioxus muscle, where it forms a strong complex with a specific target, named CaVPT (26.6 kD) (Cox 1986). The lancelet Amphioxus (Branchiostoma lanceolatum), considered to be the closest living relative of the vertebrates, has a 5 cm-long body and the morphology of a fish. As an adult it burrows in sand and filters food from water. Because of their common characteristics, the lancelets and vertebrates are usually classified by biologists in a phylum called chordates. Sequence analysis, molecular modeling, and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis revealed (Cox et al. 1990; Théret et al. 2000) that the protein is composed of two domains with structural and functional autonomy, each containing two EF-hand motifs. Because of extensive amino acid substitutions and deletions in the ion-binding loops, the N-terminal domain (N-CaVP) has no binding capacity, the only two functional binding sites being situated in the C-terminal domain (site III and IV). Expression and purification of this last domain enabled us to show that its binding properties are independent of the presence of N-CaVP and that it recognizes and binds with significant affinity the target protein (Baladi et al. 2001). Therefore, C-CaVP includes the calcium-binding sites and exhibits the main regulatory activity of the whole protein. We thus concentrated our effort to establish structure/dynamics/function relationships in the C-CaVP using NMR spectroscopy. Determination of the three-dimensional structure in solution of the calcium-saturated form and investigation of the partially-bound and free forms revealed a novel mode of metal-induced structural rearrangement and a functional asymmetry of this domain (Théret et al. 2000). The tertiary structure is similar to other Ca2+-binding proteins with two EF-hand motifs linked by a short nine-residue fragment (Fig. 1 ▶). As reflected in the interhelical angles within each motif (116 ± 5° and 90 ± 7° for sites III and IV, respectively), the bound form has an open structure, characterized by a significant exposed hydrophobic surface, in agreement with observations on other regulatory CaBP domains (Ikura 1996).

Fig. 1.

Simplified ribbon representation of the global structure of the (Ca2+)2 C-CaVP drawn with the MOLSCRIPT software (Kraulis 1991). The two EF-hands are connected by a nine-residue linker fragment (PDB code 1C7W).

The apo form of C-CaVP appears as a highly fluctuant, but still compact state. Titration experiments showed that the first calcium ion binds exclusively to site III and stabilizes only this EF-hand motif. This unusual behavior is because of a large difference (three orders of magnitude) between the intrinsic binding constants of the two sites. Binding of the second Ca2+ ion induces structural changes in site III and organizes site IV, yielding to the standard scaffold of an EF-hand pair. The large conformational and flexibility changes observed during the calcium titration may be accompanied by significant dynamic variations on different time scales. Indeed, it is now widely accepted that internal mobility of the backbone and side chains in proteins play an important role in the specificity/affinity balance in biological-relevant intermolecular interactions (Palmer 1997).

NMR spectroscopy, together with nuclear relaxation and amide exchange kinetics measurements, became a powerful method for investigation of the global and internal dynamics and flexibility in proteins over a wide scale of time constants (Palmer 1997). To complement the structure/function relationships in C-CaVP by the dynamics dimension, we initiated a relaxation study of the protein backbone. Based on the previous assignment of proton and 15N resonances in the Ca2+-saturated form (Théret et al. 2000), the nitrogen relaxation data obtained at four magnetic fields were used to map the spectral density functions of amide vectors and to estimate the microdynamic parameters at various sites along the sequence. The dynamic characteristics of the domain were analyzed in relation with the NMR-derived three-dimensional structure and the functional properties. A comparison of heteronuclear NOE (nuclear overhauser effect) of the half- and full-saturated states of C-CaVP revealed different degrees of mobility of the partially bound form, emphasizing the considerable dynamic effect of calcium binding.

Results and Discussion

15N relaxation parameters

Relaxation data were collected for 68 residues at all the magnetic fields used in this work. The excluded peaks include the two prolines (P121 and P145) and eight residues (F97/F112, D88/D85, D98/E129, and K152/R92) with superposed cross-peaks. Additional peaks were neglected because they were not assigned unambiguously (K155 and A130) or showed an unusual broadening (K132) at 400 and 500 MHz. For the first residue (W81), we only measured the relaxation of the side-chain indole amino proton. The relaxation parameters (R1, R2, and NOE), determined at four different magnetic fields and their graphic representation along the sequence, are available as supplementary material. The measured values are within the theoretically expected ranges for a molecule of this size in the absence of an important exchange contribution (Peng and Wagner 1995).

In contrast with the transverse relaxation rates and NOEs, the longitudinal relaxation rates are strongly dependent on field strength: The average value of R1 is 1.76 s−1 at 800 MHz and increases by 70% to reach 3.0 s−1 at 400 MHz. Also, the sequence variability of R1 is significantly larger at lower fields, as was already noted for eglin c (Peng and Wagner 1995). Transverse relaxation rate values R2 are clearly less sensitive to the spectrometer field, in agreement with other reported experimental observations (Peng and Wagner 1995; Fushman et al. 1997; Maciejewski et al. 2000). From 400–800 MHz the average value increases by only 21%. The four sequence-dependent R2 series show a common pattern with significantly lower rates at the two chain ends and a well localized two-phase variation in the linker segment (I114–D124). The first phase (I114–G118), corresponding to a field-dependent increase in R2 (up to 66%, relative to the average), is followed by a symmetric decrease phase (G118–D124) of comparable amplitude.

The heteronuclear steady-state NOEs, characteristic of a folded compact structure, are slightly different between the four fields, with higher values at higher magnetic fields, (Gagné et al. 1998; Maciejewski et al. 2000). Small but definite decreased NOE values are observed in a segment centered on P121, the position where a minimum was observed in the profiles of the two relaxation rates. A careful analysis of R1 and NOE profiles suggests that the area of decreased rates starts at the end of helix F and the beginning of the linker. The low (negative) NOE values observed for the N- and C-terminal ends are typical for unstructured, random coil segments (Farrow et al. 1997; Zhu et al.1998).

Overall, analysis of the relaxation parameters could be summarized by three main conclusions: (1) The sequence distribution of the experimental parameters is quite homogenous within the EF-hand motifs, including the Ca2+-binding loops; (2) the terminal ends have a characteristic behavior, with low values for the three parameters; (3) a specific pattern is observed in the linker between the two motifs, with a small segment (I114–G118) characterized by increased R2 rates, which is included in a larger fragment with a significant decrease of relaxation values.

Spectral density mapping

Starting from the relaxation parameters measured at four different fields, we mapped the spectral density functions for each of the 68 bond vectors at nine frequency values (0, 40, 50, 60, 80, 348, 435, 522, and 696 MHz). The area under the spectral density function J(ω) is the same for every amide group in the molecule, being proportional to the mean squared energy of the molecular fluctuations. For instance, for vectors having faster movements, the density function will increase at higher frequencies (ωH) and simultaneously decrease at lower frequencies (0, ωN) to conserve the total area.

The distribution of the calculated spectral densities at 0, ωN and ωH frequencies along the protein sequence are represented in Figure 2 ▶. The profiles are globally similar at the four magnetic fields, but the absolute values show a considerable field-dependence in the 15N resonance range. The sequence dependence of the spectral density function informs on the structural distribution of the various molecular fluctuations determining 15N relaxation and heteronuclear magnetization transfer. For a given HN-N vector, J(ω) decreases from ∼1.5 nsec/rad at zero frequency to < 20 psec/rad. From the Jeff(0) profile (Fig. 2a ▶) it is clear that in the two polypeptide terminals (four residues in the N-terminal and nine in the C-terminal) the density of the slow movements is considerably lower than in the rest of the backbone. A similar trend but with lower amplitude may be seen at 15N frequencies (< 80 MHz). As the total surface under the distribution function is constant, the smaller density values at low frequencies are accompanied by larger densities at high frequencies (Fig. 2c ▶).

Fig. 2.

Spectral density values along the sequence in (Ca2+)2 C-CaVP at 308K. Spectral densities Jeff(0), J(ωN), and J(0.87*ωH) are determined as described in the text. (a) Spectral densities values Jeff(0) in the (Ca2+)2 C-CaVP at 308K at the four fields. Jeff(0;40 MHz) in (blue ♦), Jeff(0;50 MHz) in (purple ▪), Jeff(0;60 MHz) in (yellow ▴), and Jeff(0;80 MHz) in (red ▪). Values of J(0), with no exchange contribution (equation 5), are plotted vs. the protein sequence with • for simple Lipari-Szabo approach and with ◯ for extended Lipari-Szabo approach. (b) J(ωN) at 40 MHz (blue ♦), 50 MHz (purple ▪), 60 MHz (yellow ▴), and 80 MHz (red ▪). (c) J(0.87ωH) at 400 MHz (blue ♦), 500 MHz (purple ▪), 600 MHz (yellow ▴), and 800 MHz (red ▪).

The amide vectors in the two EF-hand motifs have almost the same spectral density values, suggesting that their dynamics features are roughly homogeneous. In contrast, in the linker loop a specific pattern for each of three profiles may be noted. Between I114 and T123, J(ωH) shows a slightly increased shoulder, whereas J(ωN) is decreased significantly. In the same fragment, the spectral density function at zero frequency has a more complex two-phase behavior. First, there is a positive phase (I114–G118) with a relatively large increase of spectral density values (up to 30% for V117). This observation is characteristic of a slow exchange process between two or more conformations having a kinetic rate which is much larger than the difference in 15N resonance frequencies. The second phase, observed at the end of the linker (G118–D124) centered on P121, represents decreased spectral density values relative to those of the EF-hand backbone. Similar to the two protein terminals but to a lesser extent, this part of the linker is characterized by a low content of slow movements, balanced by an increase in sub nanosecond, fast fluctuations.

These observations suggest strongly that the paucity of NOE information and the bad quality of the linker structure (Théret et al. 2000) are mainly because of a dynamic disorder in the sub nanosecond time range, as in the chain terminals, but also because of much slower exchange processes.

Rotational diffusion anisotropy

Using the atomic coordinates of the NMR-derived average structure of C-CaVP (Théret et al. 2000), we calculated first the components of the diagonalized tensor of inertia momentum. Considering only the protein core having a well-defined structure, we obtained the following ratios of the relative moments: 1.00 : 0.89 : 0.55, suggesting that the molecule has a slightly asymmetric shape. Tests of the axially symmetric hypothesis, using the R2/R1 ratios in well defined segments and the software developed by Dosset et al. (2000), showed no statistically significant improvement in the χ2 value relative to the isotropic case. Accordingly, C-CaVP is assumed to have only a small degree of diffusion anisotropy, which may not affect considerably the microdynamic parameters, particularly the generalized order parameter (Tjandra et al. 1995). Dynamic analysis of other proteins with similar inertia momentum ratios led to a similar conclusion (Zajicek et al. 2000). The isotropic global diffusion is considered to be a good model for the C-CaVP in the present experimental conditions.

Correlation time of the overall rotational diffusion

Estimation of dynamic molecular parameters from spectral density functions permits a more explicit description of the actual motions of the protein backbone. The first parameter to be quantified is the correlation time of the global rotational diffusion, which was obtained for each heteronuclear vector by fitting the spectral density values to a two-Lorentzian function (see equation 2). To minimize the unsuitable contribution of slow exchange processes, the spectral density functions at zero frequency, Jeff400(0), Jeff500(0), Jeff600(0), and Jeff800(0), were excluded at this step. Fitting the remaining eight experimental J(ω) values for each of the 36 HN-N selected vectors within regular secondary structures to the two-Lorentzian function, we obtained an average global correlation time of 3.2 ± 0.35 nsec/rad. This value is situated at the lower limit of the range observed in globular proteins of similar length (Maciejewski et al. 2000; Tillett et al. 2000), probably because of the reduced size of the well-organized, compact structure of C-CaVP. Indeed, as is the case for other engineered isolated domains, the N- and the C-terminal ends (six and nine residues, respectively) are highly flexible and lack a persistent structure in solution (Théret et al. 2000). The compact core is therefore constituted by only 80% of the total number of residues, resulting in faster Brownian diffusion.

Order parameter

With a fixed value for the global correlation time (τc = 3.2 nsec), the dynamic parameters were estimated within the simple (S2 and τe) and extended (Sf2, S2, τs, and τf) Lipari-Szabo approach for each of the 68 resolved amide groups. Among them, 52 could fit to the simple model of Lipari-Szabo, six to the extended model (R83, Q84, D86, S154, G118, and E119), whereas data for 10 residues could not be fit to any model (W81, V82, E120, L122, and the last six residues).

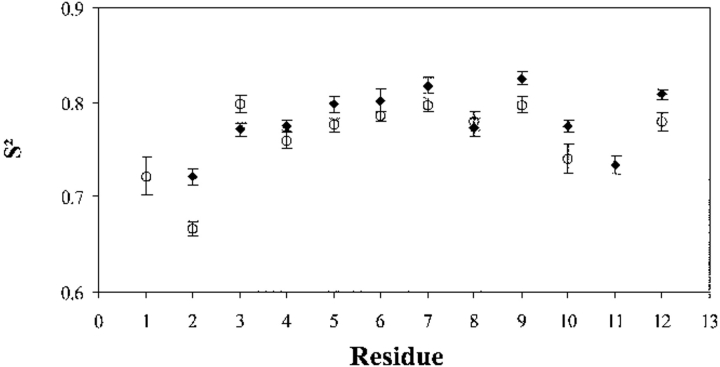

The order parameter (S2) reflects the amplitude of the fast internal motion of the HN-N bond vectors in the picosecond-to-nanosecond time range. An increased flexibility is observed for the residues of the N- and C-terminal ends. For instance, S2 decreases progressively from 0.77 to 0.20 over the last nine residues of the C-terminal segment, indicating larger amplitude motions with time constants in the range of 20–75 nsec. The S2 values over the two EF-hands are quite homogeneous, with an average of 0.77 nsec (Fig. 3 ▶), indicating that the backbone of the Ca2+-binding motifs behaves like a rigid unit, with highly restricted movements in the time range (internal correlation time) of 0 to 20 nsec. According to the average order parameters of the two ion-binding loops (0.78 ± 0.03 and 0.76 ± 0.04 for sites III and IV, respectively), the two loops and the adjacent helices have a similarly restrained fast motion. This is in agreement with the good definition of these fragments in the solution structure (Théret et al. 2000) and is mainly because of the intraloop hydrogen bonds and ion-protein interactions.

Fig. 3.

Order parameters S2 for the backbone HN-H vectors of Ca2+ saturated C-CaVP.

Comparison of the S2 profiles in the two binding loops (Fig. 4 ▶) shows an interesting common feature: At the beginning, the backbone has a larger amplitude of fast motion and becomes progressively more rigid toward the C-end. Generally, amide vectors in binding site III have larger order parameters than those in site IV, suggesting that the second site is more flexible globally. The lower amplitude of the fast movement in site III could be related to the greater Ca2+ affinity of this site, as estimated by flow dialysis (Petrova et al. 1995) or NMR titration (Théret et al. 2000). Other dynamic factors on longer time scales, as well as structure characteristics involving the neighboring helices, should be invoked to explain the considerable affinity difference between the two sites.

Fig. 4.

Backbone order parameters in Ca2+ binding sites III (♦) and IV (○) of Ca2+-saturated C-CaVP. The abscissa indicate the position of the residues in the consensus sequence of the ion-binding loop.

Among the residues included in the Ca2+-binding loop, A99 and E136 have the lowest order parameters (0.72 and 0.66, respectively) (Fig. 3 ▶), reflecting a larger amplitude of the fast motions at these sites. For E136, this is corroborated clearly by the increased value of the spectral density function at zero frequency, accompanied by a significant decrease at nitrogen resonance frequencies (Fig. 2 ▶). The two residues occupy the second position in the Ca2+-binding loops in a highly conserved reverse turn type I structure (Herzberg and James 1985), but their amide group are not involved directly in a hydrogen bond. Similar properties have been described for the corresponding residues in Drosophila CaM (Barbato et al. 1992), parvalbumin (Baldellon et al. 1998), (Moncrieffe et al. 2000), cNTnC (Spyracopoulos et al. 1998), apo-sNTnC (Gagné et al. 1998). Explanation of the dynamic specificity of the residues in this loop position is currently a matter of speculation, but localization of the vectors in a hinge position between two rigid structural units (the α-helix and the ion-binding loop) appears to be a determining factor (Baldellon et al. 1998).

A regular decrease of order parameters, associated with a significant increase of the internal correlation time (up to 75 nsec), is observed in the linker fragment between Q115 and D124, with a minimum at P121 (Fig. 3 ▶). These S2 values are intermediate between those reported for rat α-parvalbumin (Baldellon et al. 1998) and apo N-sTnC (Gagné et al. 1998), in which the linker shows no decreased S2 (> 0.8), and the calbindin D9k (S2 ∼ 0.28) (Kördel et al. 1992), Ca2+-saturated CaM (S2 ∼ 0.5) (Barbato et al. 1992), or C-domain of CaM at low Ca2+ concentrations (Malmendal et al. 1999) (S2 = 0.55). This pattern of the S2 parameter indicates that the fast movement of the linker amide vectors has an increasing amplitude when going toward the middle of the sequence connecting the two EF-hand motifs.

Exchange contribution

As suggested by the R2 and Jeff(0) profiles (Fig. 2a ▶), a small segment within the linker sequence undergoes a slow conformational process, which determines an increase of the transverse relaxation rate and of the spectral density at low frequencies. Correction of the Jeff(0) values under the assumption of a field-dependent exchange contribution (see equation 5) results in a more uniform spectral density profile with reduced values (the mean value decreases from 1.5 nsec/rad to 0.94 nsec/rad). The negative deflection of the J(0) in the fragment centered on P121 is now better defined. Fitting the Jeff(0) data to equation 5 also provides the Φ and Rex values, which are represented along the protein sequence in Figure 5 ▶. Rex rate is a contribution to the R2 relaxation rate accounting for exchange processes modulating the 15N chemical shift, whereas the proportionality factor Φ depends on parameters describing the spectral and kinetic characteristics of the exchange. For instance, in a simple model of a two-site exchange process, Φ = papb (Δδ)2 τex, in which pa and pb are the fractional populations of the two sites, Δδ is the 15N chemical shift difference, and τex is the exchange time constant. It may be observed that for the residues included in the two EF-hand motifs, the Φ values are almost distributed homogeneously with an average of < 1 × 10−17 sec/rad and a relatively low standard deviation. In connection with the J(0) profile (Fig. 2 ▶), this may suggest the existence of a wide spread-exchange process with a significant contribution to the R2 relaxation rate (the Rex values are between 0.5 and 2 Hz). Similar exchange backgrounds of 1–2 s−1, usually with larger estimated errors, in the Rex profile were noted in a number of proteins (Peng and Wagner 1995; Vis et al. 1998; Moncrieffe et al. 2000). Three types of global exchange processes could be invoked to explain this component: (Ca2+)2/(Ca2+)1 equilibrium, protein aggregation, or conformational equilibrium within the Ca2+ saturated state. Ca2+ titration of C-CaVP monitored by NMR spectroscopy (Théret et al. 2000) showed that the exchange between different Ca2+-dependent states has a slow kinetics on the chemical shift scale. For instance, the minimum observed chemical shift difference between (Ca2+)1 and (Ca2+)2 states corresponds to G103 amide proton and is ∼0.2 ppm. Accordingly, the kinetic off constant should be on the order of 50 s−1 ( koff ≪ 628 s−1). Consequently, such a process could not influence significantly the R2 relaxation rate, as the refocusing π pulses during the CPGM sequence exclude every exchange, which is much slower than 2000 s−1. On the other hand, considering the short correlation time estimated in the present experimental conditions (3.2 nsec), the sample should be largely in a monomer form. This renders unlikely an exchange contribution from dynamic equilibrium between oligomer forms. Therefore, conformational changes between slightly different ion-saturated conformers having different chemical shifts for 15N resonances may explain the background of the Φ profile.

Fig. 5.

(a) Exchange parameter Φ plotted versus the protein sequence. The Φ value is calculated by fitting the values of Jeff(0) obtained for the four different magnetic fields to equation 5. The exchange contributions to the transverse relaxation rate (Rex), calculated for each field are shown in b: Rex400 in blue ♦, Rex500 in purple •, Rex600 in yellow ▴, and Rex800 in red ▪.

The Φ profile points to a well-defined exchange contribution in the first half of the linker sequence centered on G118. The corresponding Rex maximum value varies between 2.3 and 10.3 Hz, depending on the magnetic field (Fig. 5b ▶) outside of the typical estimated errors for the transverse relaxation rates. This reflects a slow (μsec–msec) movement, animating several residues from the beginning of the linker. Isomerization of disulfide bonds (Ye et al. 1999), or cis-trans equilibrium in peptidyl-prolyl bonds (Guignard et al. 2000) were mentioned in some cases as the cause or as a favorable environment for such a slow conformational exchange. As the slow movements in C-CaVP are centered on P121, it is tempting to consider them as a result of cis-trans isomerization of the E120-P121 bond. It is interesting to note that proline 43 (P43) in the calbindin D9k linker was shown (Chazin et al. 1989) to be the source of a slow conformational disorder in the range of 10−1 to 10−2 s−1. The dynamic studies on this protein were subsequently performed on a variant in which P43 was substituted by a glycine residue. A proline residue also exists in the linker segment of the N-terminal domains of TnC (P53) and CaM (P43). Detailed dynamic analysis of TnC domain (Gagné et al. 1998) has indeed revealed a small exchange contribution at the residue preceding the proline residue. Taken together, these facts suggest that the exchange component observed in the 15N relaxation of linker amides, although faster than the usual cis-trans Pro isomerism, should be related to the proline insert in the CaVP sequence.

Therefore, the linker fragment of C-CaVP exhibits a complex dynamic behavior, combining a high amplitude fast motion, which covers almost all of the included amide vectors and a slow exchange process, mainly involving the first half. Such an intricate pattern of motions on fast and slow time scales were never observed previously in any other Ca2+ binding proteins, but was noted in several regions of ribonuclease HI (Mandel et al. 1995).

Despite the different types of fast and slow movements exhibited by the linker fragment, the two EF-hand motifs are held together strongly by hydrogen bonds (within the antiparallel β-sheet) and many hydrophobic interactions between apolar side chains from the four α-helices. This fact is reflected in the high melting temperature of the Ca2+-saturated protein, as revealed by CD spectroscopy and microcalorimetry (Baladi et al. 2001). Therefore, C-CaVP behaves like a compact domain, characterized by a single rotational correlation time and various types of internal motions with a large range of timescales from tens of picoseconds to microseconds and milliseconds. The observed NOE restraints involving residues from the linker fragment are considerably smaller and are mainly short distance, accounting for the larger structural dispersion of the calculated NMR structures in this area (Théret et al. 2000). The present results suggest that the poor structural definition could be associated mainly with the specific local dynamics of the backbone.

Backbone dynamics and ion binding

The regulatory domain of CaVP displays a novel mode of conformational rearrangement during stepwise calcium binding. An intermediate binding state, with a Ca2+ ion bound to site III and the unbound site IV, was isolated during an NMR titration experiment and characterized from the structural point of view (Théret et al. 2000). The bound site III was assigned and structure calculations revealed a global fold similar (but not identical) to that determined in the Ca2+-saturated state. In contrast, because of the poor dispersion, the resonances of site IV could not be assigned using binuclear spectra, but the overall aspect of HSQC spectrum, decreased CD signal, and the absence of persistent NOE interactions suggested a highly fluctuating structure. The residues forming the β-strand of site III (V104–D106) have chemical shifts and dihedral angles typical for antiparallel β-sheet, but no characteristic long-distance NOE connectivities with the complementary strand were observed. Comparative analysis of the dynamic properties of the fully saturated and partially-bound molecules may complement the structural investigation, providing useful information for a better understanding of the binding process. In the absence of a complete assignment of the partially bound form, we considered in a first stage only the heteronuclear steady-state NOEs, which give a rough estimation of the backbone dynamics. Figure 6 ▶ shows a comparison of this relaxation parameter, measured for the saturated (Ca2+)2 and partially bound (Ca2+)1 forms of C-CaVP at 500 MHz. As may be seen in the figure, the heteronuclear NOEs of the first half of the molecule are highly similar in the two molecular states. This observation is in agreement with the regular structure found for this EF-hand motif in the partially (one Ca2+) -bound form (Théret et al. 2000). In contrast, the second half (unbound) shows dramatically decreased and highly dispersed heteronuclear NOEs, with values between −1.4 and 0.4. The low values observed for site IV of (Ca2+)1 C-CaVP are characteristic of a highly flexible backbone (fast motions with larger amplitudes), as expected from the proton chemical shifts and NOE data. For instance, the heteronuclear NOE values observed in the monomeric, disordered melittin were between −1.5 and −0.3, whereas in folded state (tetrameric), the observed values increase up to +0.7 (Zhu et al. 1998). In a comparative study of the SH3 domain, Farrow et al. (1997) found that the guanidinium chloride unfolded state is not dynamically homogeneous: The residues in the middle of the sequence are considerably less flexible (positive heteronuclear NOE) than the protein extremities, which have negative NOEs (down to −0.9). The large scattering of NOE data observed here for C-CaVP suggests that the second half of the domain is not simply an extended, completely flexible chain but possesses some dynamic characteristics of a relatively compact fold.

Fig. 6.

Heteronuclear NOEs, determined at 11.74 T and 308K for two binding states of C-CaVP, along the sequence. Δ correspond to the NOEs of the (Ca2+)2 C-CaVP saturated form, ▪ indicate NOEs of the (Ca2+)1III C-CaVP. The box delimited by interrupted lines shows the heteronuclear NOEs of unassigned peaks in site IV.

It is interesting to note that in the fragment 112–116, representing the C-terminal half of the F helix, the heteronuclear NOEs in the partially saturated state are systematically larger than in the metal-saturated state (Fig. 6 ▶). The lower values of NOEs in this area in (Ca2+)2-C-CaVP were also observed at the other magnetic fields and are accompanied by a reduced generalized order parameter (Fig. 3 ▶). This seems to be a common characteristic for the end of α-helices, as inferred from a recent survey of a structure/dynamics database (Goodman et al. 2000). In our case, the complex dynamics, mixing fast motion, and slow conformational exchange of the contiguous linker sequence may have a destabilizing effect on the F helix. When site IV is ion-free and much more flexible, these structural and dynamic constraints are removed and the α-helix is more stable at this C-terminal end. Moreover, we can speculate that the presence of the linker with its particular dynamics may have an important contribution in maintaining a molecular form in which two contiguous EF-hand motifs have highly dissimilar internal dynamics. This partially bound form, which should be representative of the native state in cellular resting conditions, is the physiological trigger, which in the presence of the natural target (CaVPT) induces structure in site IV and facilitates binding of the second Ca2+ ion.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first report of a 15N relaxation study based on experimental data recorded at four different magnetic fields. In addition to giving more confidence to the observed sequence dependence of the relaxation rates, the mapping of the spectral density function allows a more accurate estimation of the slow exchange processes. As the mapping of the spectral density function is performed without any assumption about the type and magnitude of the global and internal motions of the protein, the sequence-dependent analysis of the various J(ω) components reinforces the conclusions derived from the interpretation of the dynamic parameters. A significant finding of the present analysis, namely, a combination of slow exchange and larger amplitude fast movements animating the linker fragment, is thus supported by both spectral density and a model-free approach.

Materials and methods

Sample preparation

Recombinant C-CaVP (W81–S161) was overexpressed in Escherichia coli (strain BL21 DE3) containing the insert vector pET24a. 15N labeling was performed in minimal medium (M63) with (15NH4)2SO4 (2g/L) as the sole source of nitrogen. The sample was purified as described previously (Baladi et al. 2001). NMR samples (1 mM) were prepared by dissolving the protein in 92% 1H2O/8% 2H2O containing deuterated Tris buffer (20 mM), 100 mM KCl, and 6 mM CaCl2 at pH 6.5.

Experimental procedures

The heteronuclear relaxation experiments were performed at 308K at four different fields: 9.39 T (Bruker 400 MHz, CBS, Montpellier), 11.74 T (Varian Unity-500, Institut Curie), 14.1 T (Bruker 600 MHz, CBS, Montpellier), and 18.7 T (Bruker 800 MHz, ICSN, Gif-sur-Yvette). The R1 relaxation rate was measured from successive spectra in which magnetization relaxes as exp(−R1 × t). The transverse relaxation rate (R2) was determined using a Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill pulse sequence with a spin echo time delay of 0.9 msec. Recycle delays of 2.5 sec were used at the beginning of the R1 and R2 pulse sequences. Steady-state 1H-15N NOE was determined from spectra pairs recorded with and without proton saturation. Both experiments start with a 5 sec recycle delay, but during the last 3 sec of this delay in the saturation experiment the protons were irradiated by 120° pulses every 5 msec. The pulse sequences used in the present experiments were adapted from those kindly provided by Lewis Kay (Farrow et al. 1994).

Data processing

Spectra processing was performed with the program Felix 97.0 (MSI). The size of the frequency domain matrix was 1024 × 512 real points. Baseline correction was performed on all the spectra using the FACELIFT program (Chylla and Markley 1993). Peak picking and height measurement were performed with the specialized routines of the Felix package. Uncertainties in the peak intensities were evaluated on the basis of the standard deviation of the noise in a few rows from spectra with intermediate relaxation delays for R1 and R2 experiments. Relaxation rates R1 and R2 were obtained by least-squares fitting of peak intensities to a two-parameter, single-exponential function via an in-house computer program. Errors in relaxation rates were estimated from the uncertainties in the peak heights and in the exponential fit or by Monte Carlo simulations. Based on statistical evaluation (χ2 comparison), the mono-exponential fit with two parameters was preferred. The steady-state NOE was calculated as Isat/Inonsat, in which Isat and Inonsat are the steady-state peak intensities measured with and without proton saturation, respectively. Estimation of NOE uncertainties was based on uncertainties of the peak heights and the law of uncertainty propagation.

Spectral density mapping

A simplification of this mapping procedure, based on the fact that the spectral density function is almost constant in the high-frequency limits between ωH + ωN and ωH − ωN, permits replacement of J(ωH + ωN), J(ωH) and J(ωH − ωN) by an average value, < J(ωH) >, taken as J(0.87ωH) (Farrow et al. 1995). The reduced spectral density function can be mapped with only three experimental parameters (R1, R2, and the heteronuclear NOE), at three frequencies (0, ωN, and ωH) for each spectrometer field (Ishima and Nagayama 1995; Peng and Wagner 1995). The value used for the proton/nitrogen bond length was rHN = 1.02 Å and the 15N chemical shift anisotropy was assumed to be −170 ppm (Tjandra et al. 1996).

Uncertainties in the J(ω) were estimated as the weighted sum of squared components (Peng and Wagner 1992):

|

1 |

in which the weights (cij) are the rate coefficients of the linear relations between J(ω) and relaxation parameters, and δRi are the experimental uncertainties associated with the relaxation rates.

Lipari-Szabo approach

A simplified and practical method for translating the dynamics information contained in the relaxation rates in terms of molecular parameters, without any assumption on the type of motion, is to decompose the correlation function (and therefore the spectral density) of the amide vector movement into several independent additive components. The original model-free approach proposed by Lipari and Szabo (1982) assumes a separation of the global molecular rotation from internal movement. The spectral density function is therefore given by the expression:

|

2 |

in which τc is the global rotational correlation time, τi is related to the effective internal correlation time, and the global correlation time by the relation: 1/τi = 1/τe + 1/τc. S2 is the generalized order parameter (0 < S2 < 1 ) characterizing the amplitude of the internal motions of the HN-N bonds in the picosecond-to-nanosecond range. In a more elaborate analysis assuming two types of internal motions, a fast one in picosecond range and a slow one in nanosecond range, Clore et al. (1990) proposed an extended expression:

|

3 |

with 1/τ′f = 1/τf + 1/τc and 1/τ′s = 1/τs + 1/τc. τf and τs are the effective correlation times for the internal motions on the fast and slow time scale, respectively (τf < τs < τc). S2 = Sf2Ss2 is the total generalized order parameter, characterizing the amplitude of slow and fast motions of the HN-N vector.

The least-squares fit of the spectral density functions using these two approaches (see equations 2 or 3) enabled us to obtain dynamic parameters of the various HN-N groups. For each heteronuclear vector, we finally retained the fitting result of one of the two analyses (giving physically meaningful results), based on the fit quality comparison. The statistical F-test, based on the computation of the F ratio:

|

4 |

was used to decide on the fit improvement accompanying the increased number of parameters (from 2 to 4). Subscripts 1 and 2 stand for the simple and extended approaches, respectively, χi is the sum-of-squares, and δfi represents the number of degrees of freedom (the number of experimental relaxation parameters minus the number of fit parameters). If the simpler model is correct, an F ratio near 1.0 is expected. If the F ratio is > 1.0, the more complicated model should be retained.

Evaluation of the exchange contribution

For each residue, the dynamic parameters (e.g., S2, τf, and τs) obtained by fitting the exchange-independent spectral density values J(ω > 0), could be used to back-calculate the values J(0), which are free of exchange contributions. The zero-frequency information, expressed by an effective value Jeff(0), could be considered as the sum of two contributions because of slow reorientation, i.e., J(0), and exchange processes (Rex) (Peng and Wagner 1995):

|

in which λ is a constant for each static magnetic field. As the exchange term depends on the chemical shift difference between the alternative conformations, its magnitude will be proportional to the square of the Larmor frequency (Rex = ωN2 Φ) (Peng and Wagner 1995). Therefore, Jeff(0) may be written:

|

5 |

in which Φ is a proportionality factor specific for the considered exchange process. Φ (and, therefore, Rex) can be obtained by fitting experimental Jeff(0) values to equation 5.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, the Institut Curie, and the Swiss National Science Foundation. We thank Carine van Heijenoort and Christian Roumestand for recording the experiments at 400, 600, and 800 MHz. We are indebted to Lewis E. Kay for providing pulse sequences for relaxation experiments and to Sibyl Baladi and Hiroshi Sakamoto for help in the first phase of this study.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Abbreviations

CaBP, calcium binding protein

CaVP, calcium vector protein

C-CaVP, C-terminal domain of CaVP (81-161)

N-CaVP, N-terminal domain of CaVP (1-86)

CaM, calmodulin

TnC, troponin C

cTnC, cardiac troponin C

sTnC, skeletal troponin C

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/

References

- Baladi, S., Tsvetkov, P., Petrova, T., Takagi, T., Sakamoto, H., Lobachov, V.M., Makarov, A.A., and Cox, J.A. 2001. Folding units in calcium vector protein of amphioxus: Structural and functional properties of its N- and C-terminal halves. Protein Sci. 10 771–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldellon, C., Alattia, J.-R., Strub, M.-P., Pauls, T., Berchtold, M.W., Cavé, A., and Padilla, A. 1998. 15NMR relaxation studies of calcium loaded parvalbumin show tight dynamics compared to those of other EF-hand proteins. Biochemistry 37 9964–9975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbato, G., Ikura, M., Kay, L.E., Pastor, R.W., and Bax, A. 1992. Backbone dynamics of calmodulin studied by 15N relaxation using inverse detected two-dimensional NMR spectroscopy: The central helix is flexible. Biochemistry 31 5269–5278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge, M.J., Bootman, M.D., and Lipp, P. 1998. Calcium - A life and death signal. Nature 395 645–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chazin, W.J., Kördel, J., Drakenberg, T., Thulin, E., Brodin, P., Grundström, T., and Forsén, S. 1989. Proline isomerism leads to multiple folded conformations of calbindin D9k: Direct evidence from two-dimensional 1H NMR spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 86 2195–2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chylla, R.A. and Markley, J.L. 1993. Simultaneous basepoint correction and signal recognition in multidimensional NMR spectra. J. Magn. Reson. B102 148–154. [Google Scholar]

- Clore, G.M., Szabo, A., Bax, A., Kay, L.E., Driscoll, P.C., and Gronenborn, A.M. 1990. Deviations from the simple two-parameter model-free approach to the interpretation of nitrogen-15 nuclear magnetic relaxation of proteins. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 112 4989–4991. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, J.A. 1986. Isolation and characterization of a new Mr 18,000 protein with calcium vector properties in amphioxus muscle and identification of its endogenous target protein. J. Biol. Chem. 261 13173–13178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, J.A., Alard, P., and Schaad, O. 1990. Comparative molecular modeling of Amphioxus calcium vector protein with calmodulin and troponin C. Protein Eng. 4 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosset, P., Hus, J.-C., Blackledge, M., and Marion, D. 2000. Efficient analysis of macromolecular rotational diffusion from heteronuclear relaxation data. J. Biomol. NMR 16 23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falke, J.J., Drake, S.K., Hazard, A.L., and Peersen, O.B. 1994. Molecular tuning of ion binding to calcium signaling proteins. Quart. Rev. Biophys. 27 219–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow, N.A., Zhang, O., Forman-Kay, J.D., and Kay, L.E. 1997. Characterization of the backbone dynamics of folded and denaturated states of an SH3 domain. Biochemistry 36 2390–2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow, N.A., Zhang, O., Szabo, A., Torchia, D.A., and Kay, L.E. 1995. Spectral density function mapping using 15N relaxation data exclusively. J. Biomol. NMR 6 153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow, N.A., Muhandiram, R., Singer, A.U., Pascal, S.M., Kay, C.M., Gish, G., Shoelson, S.E., Pawson, T., Forman-Kay, J.D., and Kay, L.E. 1994. Backbone dynamics of a free and phosphopeptide-complexed Src homology 2 domain studied by 15N NMR relaxation. Biochemistry 33 5984–6003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fushman, D., Cahill, S., and Cowburn, D. 1997. The main-chain dynamics of the dynamin pleckstrin homology (PH) domain in solution: Analysis of 15N relaxation with monomer/dimer equilibration. J. Mol. Biol. 266 173–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagné, S.M., Tsuda, S., Spyracopoulos, L., Kay, L.E., and Sykes, B.D. 1998. Backbone and methyl dynamics of the regulatory domain of troponin C: Anisotropic rotational diffusion and contribution of conformational entropy to calcium affinity. J. Mol. Biol. 278 667–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, J.L., Pagel, M.D., and Stone, M.J. 2000. Relationship between protein structure and dynamics from a database of NMR-derived backbone order parameter. J. Mol. Biol. 295 963–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guignard, L., Padilla, A., Mispelter, J., Yang, Y.-S., Stern, M.-H., Lhost, J.-M., and Roumestand C. 2000. Backbone dynamics and solution structure refinement of the 15N-labeled human oncogenic protein p13MTCP1: Comparison with X-ray data. J. Biomol. NMR 17 215–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg, O. and James, M.N.G. 1985. Common structural framework of the two Ca2+/Mg2+ binding loops of troponin C and other Ca2+ binding proteins. Biochemistry 24 5298–5302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikura, M. 1996. Calcium binding and conformational response in EF-hand proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 21 14–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishima, R. and Nagayama, K. 1995. Protein backbone dynamics revealed by quasi spectral density function analysis of amide N-15 nuclei. Biochemistry 34 3162–3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kördel, J., Skelton, N.J., Akke, M., Palmer, A.G.III, and Chazin, W.J. 1992. Backbone dynamics of calcium-loaded calbindin D9k studied by two-dimensional proton-detected 15N NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry 31 4856–4866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraulis, P. 1991. MOLSCRIPT: A program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24 946–950. [Google Scholar]

- Lipari, G. and Szabo, A. 1982. Model-free approach to the interpretation of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance relaxation in macromolecules. 1. Theory and range of validity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 104 4546–4559. [Google Scholar]

- Maciejewski, M.W., Liu, D., Prasad, R., Wilson, S.H., and Mullen, G.P. 2000. Backbone dynamics and refined solution structure of the N-terminal domain of DNA polymerase b. Correlation with DNA binding and dRP lyase activity. J. Mol. Biol. 296 229–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmendal, A., Evenäs, J., Forsén, S., and Akke, M. 1999. Structural dynamics in the C-terminal domain of calmodulin at low calcium levels. J. Mol. Biol. 293 883–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel, A.M., Akke, M., and Palmer, III, A.G. 1995. Backbone dynamics of Escherichia coli ribonuclease HI: Correlations with structure and function in an active enzyme. J. Mol. Biol. 246 144–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncrieffe, M.C., Juranic, N., Kemple, M.D., Potter, J.D., Macura, S., and Prendergast, F.G. 2000. Structure-fluorescence correlations in a single tryptophan mutant of carp parvalbumin: Solution structure, backbone and side-chain dynamics. J. Mol. Biol. 297 147–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, III, A.G. 1997. Probing molecular motion by NMR. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7 732–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J.W. and Wagner, G. 1992. Mapping of spectral density functions using heteronuclear NMR relaxation measurements. J. Magn. Reson. 98 308–332. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J.W. and Wagner, G. 1995. Frequency spectrum of NH bonds in eglin c from spectral density mapping at multiple fields. Biochemistry 34 16733–16752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrova, T.V., Comte, M., Takagi, T., and Cox, J.A. 1995. Thermodynamic and molecular properties of the interaction between amphioxus calcium vector protein and its 26 kDa target. Biochemistry 34 312–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spyracopoulos, L., Gagné, S.L., Li, M.X., and Sykes, B.D. 1998. Dynamics and thermodynamics if the regulatory domain of human cardiac troponin C in the apo- and calcium-saturated states. Biochemistry 37 18032–18044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Théret, I., Baladi, S., Cox, J.A., Sakamoto, H., and Craescu, C.T. 2000. Sequential calcium binding to the regulatory domain of Calcium Vector Protein reveals functional assymmetry and is accompanied by large structural changes. Biochemistry 39 7920–7926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillett, M.L., Blackledge, M.J., Derrick, J.P., Lian, L.-Y., and Norwood, T.J. 2000. Overall rotational diffusion and internal mobility in domain II of protein G from Streptococcus determined from 15N relaxation data. Protein Sci. 9 1210–1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjandra, N., Feller, S.E., Pastor, R.W., and Bax, A. 1995. Rotational diffusion anisotropy of human ubiquitin from 15N NMR relaxation. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 117 12562–12566. [Google Scholar]

- Tjandra, N., Szabo, A., and Bax, A. 1996. Protein backbone dynamics and 15N chemical shift anisotropy from quantitative measurement of relaxation interference effects. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 118 6986–6991. [Google Scholar]

- Vis, H., Vorgias, C.E., Wilson, K.S., Kaptein, R., and Boelens, R. 1998. Mobility of NH bonds in DNA-bidnig protein HU of Bacillus stearothermophilus from reduced spectral density mapping analysis at multiple fields. J. Biomol. NMR 11 265–277. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J., Mayer, K.L., and Stone, M.J. 1999. Backbone dynamics of the human CC-chemokine eotaxin. J. Biomol. NMR 15 115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajicek, J., Chang, Y., and Castellino, F.J. 2000. The effects of ligand binding on the backbone dynamics of the kringle 1 domain of human plasminogen. J. Mol. Biol. 301 333–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L., Prendergast, F.G., and Kemple, M.D. 1998. Comparison of 15N- and 13C-determined parameters of mobility in melittin. J. Biomol. NMR 12 135–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]