Abstract

Previous studies on Escherichia coli aspartate transcarbamoylase (ATCase) demonstrated that active, stable enzyme was formed in vivo from complementing polypeptides of the catalytic (c) chain encoded by gene fragments derived from the pyrBI operon. However, the enzyme lacked the allosteric properties characteristic of wild-type ATCase. In order to determine whether the loss of homotropic and heterotropic properties was attributable to the location of the interruption in the polypeptide chain rather than to the lack of continuity, we constructed a series of fragmented genes so that the breaks in the polypeptide chains would be dispersed in different domains and diverse regions of the structure. Also, analogous molecules containing circularly permuted c chains with altered termini were constructed for comparison with the ATCase molecules containing fragmented c chains. Studies were performed on four sets of ATCase molecules containing cleaved c chains at positions between residues 98 and 99, 121 and 122, 180 and 181, and 221 and 222; the corresponding circularly permuted chains had N termini at positions 99, 122, 181, and 222. All of the ATCase molecules containing fragmented or circularly permuted c chains exhibited the homotropic and heterotropic properties characteristic of the wild-type enzyme. Hill coefficients (nH) and changes in them upon the addition of ATP and CTP were similar to those observed with wild-type ATCase. In addition, the conformational changes revealed by the decrease in sedimentation coefficient upon the addition of a bisubstrate analog were virtually identical to that for the wild-type enzyme. Differential scanning calorimetry showed that neither the breakage of the polypeptide chains nor the newly formed covalent bond between the termini in the wild-type enzyme had a significant impact on the thermal stability of the assembled dodecamers. The studies demonstrate that continuity of the polypeptide chain within structural domains is not essential for the assembly, activity, and allosteric properties of ATCase.

Keywords: Circular permutation, cooperativity, folding, fragment complementation, protein engineering, stability

Although it is known that the three-dimensional structures of proteins are determined by their primary sequences, the rules that govern the relationships among the primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures have not as yet been sufficiently defined to permit a complete understanding of protein folding, the role of domains, and the association of subunits. The in vivo formation of oligomeric proteins requires proper intramolecular interactions between different parts of individual polypeptide chains and intermolecular interactions between the chains in the multisubunit protein. For many proteins, some of the interactions can be altered by either amino acid substitutions or breaks in the polypeptide chains without substantial modification of the structure or biological function of the protein. In circularly permuted proteins, the cleavage of polypeptide chains along with the introduction of new N and C termini is accompanied by the covalent linkage of the wild-type termini using either the addition of a linker peptide or the deletion of a few residues to bring the appropriate termini closer together in space.

Frequently, the introduction of the new termini leads to a loss of continuity of the polypeptide chain within domains that generally are considered folding units. It seemed important, therefore, to compare proteins composed of such permuted chains with their counterparts in which the polypeptide fragments are independent because they still contain the wild-type termini. How efficient is the fragment complementation, and how do the proteins with fragmented chains compare in enzymatic and physical properties with the circularly permuted and wild-type proteins? Is connectivity of the polypeptide chain within a domain essential, or can the separate fragments fold sufficiently for docking and forming a stable domain?

Circular permutation of proteins, which was pioneered by Goldenberg and Creighton (Goldenberg and Creighton 1983) using chemical methods, has been achieved subsequently through molecular genetic approaches for the construction of genes with permuted coding sequences. Studies on a variety of proteins have been summarized by Heinemann and Hahn (1995). More recent studies of circularly permuted proteins include dihydrofolate reductases (Buchwalder et al. 1992; Protasova et al. 1994; Uversky et al. 1996; Nakamura and Iwakura 1999), the catalytic (c) polypeptide chain of E. coli aspartate transcarbamoylase (aspartate carbamoyltransferase, carbamoyl phosphate: l-aspartate carbamoyltransferase, EC 2.1.3.2) (Yang and Schachman 1993a; Graf and Schachman 1996; Zhang and Schachman 1996), ribonuclease T1 (Mullins et al. 1994; Garrett et al. 1996), Dsb A (Hennecke et al. 1999), barnase (Tsuji et al. 1999), and chymotrypsin inhibitor 2 (Otzen and Fersht 1998). Studies on the SH3 domain of α-spectrin (Viguera et al. 1995, 1996) indicated that changing the order of secondary structural elements caused by the permutation does not affect the three-dimensional structure of the protein, but it does alter the protein-folding pathway. The three-dimensional structures of circularly permuted variants of several proteins (Hahn et al. 1994; Viguera et al. 1996; Pieper et al. 1997; Chu et al. 1998; Wright et al. 1998) have been determined and were shown to be very similar to their wild-type counterparts.

In most circularly permuted proteins, the newly introduced N and C termini are located in loops or turns at the surface of the molecules and have little interactions with other regions of the protein. Nonetheless, permuted monomeric proteins sometimes are not as stable as their wild-type counterparts. Whether this decreased stability is attributable to the strain caused by the formation of a covalent bond linking regions near the original N and C termini or to the flexibility and introduction of charged residues resulting from the cleavage at the other site is generally not clear. Having available both circularly permuted proteins and their counterparts composed of polypeptide fragments may aid in interpreting such findings.

Polypeptide fragment complementation studies have been used to address a number of biological problems including protein folding. Early studies using limited proteolytic or chemical cleavage of different proteins yielded fragments that can reassociate in vitro to form active proteins. Among these were ribonuclease (Richards 1958; Richards and Vithayathil 1959), staphylococcal nuclease (Taniuchi et al. 1977), cytochrome c (Taniuchi et al. 1986; Fisher and Taniuchi 1992), cytochrome b5 reductase (Strittmatter et al. 1972), human pituitary growth hormone (Li and Bewley 1976), thioredoxin c (Holmgren and Slabay 1979), alanine racemase (Galakatos and Walsh 1987), the c chain of E. coli ATCase (Powers et al. 1993), trp repressor (Tasayco and Carey 1992), and barnase (Kippen et al. 1994). These protease-generated fragments are thought to represent well-defined structural units or domains linked through a flexible, exposed peptide. Protein engineering, through gene manipulation, has also been used to generate protein fragments either separately expressed in different cells or coexpressed in vivo. Thermostable alanine racemase (Toyama et al. 1991) has been reconstituted from two fragments that are cloned into a single vector and coexpressed in the same cells. Escherichia coli iosleucyl-tRNA synthetase (Shiba and Schimmel 1992) has been reconstituted in vivo from two fragments which are cloned into separate vectors but coexpressed in the same cells.

In complementation studies on ATCase (Yang and Schachman 1993b), active enzyme was formed from polypeptide fragments of the c chains either expressed separately or coexpressed in E. coli. The observations on ATCase are of particular interest, because the disruption of the continuity of the chain occurred within the structural region generally identified as the aspartate-binding domain. Each polypeptide expressed independently was insoluble, but mixing them in 6.5 M urea followed by removal of the denaturant yielded active enzyme in good yield (Yang and Schachman 1993b). In parallel studies (Powers et al. 1993), it was shown that limited proteolysis of the catalytic (C) trimer led to the hydrolysis of a single peptide bond between residues 240 and 241, with neither disruption of the trimeric structure nor loss of enzyme activity. The enzyme molecules containing the fragmented chains, produced both by genetic manipulation and by proteolysis, lacked allosteric properties. Similarly, dodecamers containing circularly permuted c chains with N and C termini in the same region were devoid of the allosteric properties characteristic of wild-type ATCase. Subsequently, other studies of ATCase containing circularly permuted c chains with termini in diverse regions of the structure yielded enzyme exhibiting homotropic and heterotropic effects (Zhang and Schachman 1996; Beernink et al. 2001). It was of interest, therefore, to perform companion studies on ATCase variants containing fragmented c chains along with the analogous enzyme composed of intact, circularly permuted c chains. As shown here with four ATCase variants composed of fragmented c chains and the analogous molecules containing circularly permuted chains, the two types of dodecamers with new N and C termini in each of the domains of the c chains have comparable enzyme activities and thermal stabilities, exhibit the characteristic allosteric properties of wild-type ATCase, and undergo similar ligand-promoted conformational changes.

Results

Construction of ATCase molecules containing fragmented and circularly permuted catalytic polypeptide chains

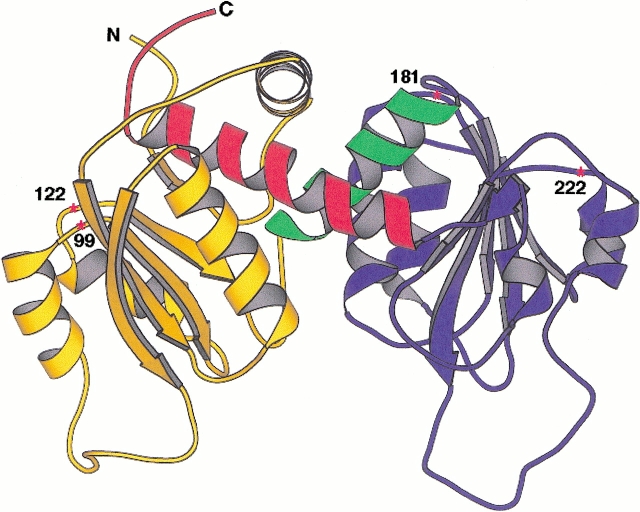

Crystallographic studies of ATCase (Honzatko and Lipscomb 1982; Kim et al. 1987; Ke et al. 1988; Lipscomb 1994) showed that the c chains in each C trimer are folded into an N-terminal, carbamoyl phosphate-binding domain containing residues 1–134, and a C-terminal, aspartate-binding domain of residues 150–284, which are connected by two α helices (residues 135–149 and 285–305), which comprise a hinge between the domains. The latter helix, which crosses over from the C-terminal domain and threads through the N-terminal domain, is followed by a short, flexible pentapeptide terminating at residue 310, which is located about 14 Å from the N-terminal residue. Experiments with the truncated pyrB gene, which encodes the c chain of ATCase, demonstrated that the helix comprising residues 285–305 was essential for the in vivo formation of active ezyme (Peterson and Schachman 1991). However, the last five residues could be eliminated without loss of enzyme activity or allosteric properties. Since residue 306 is only about 5 Å from the N terminus, the linkages used for circular permutation of the c chain involved either residues 306 to 1 or the insertion of a flexible linker peptide of six amino acid residues, thereby providing for a peptide bond between residues 316 and 1 (Yang and Schachman 1993a; Zhang and Schachman 1996). Figure 1 ▶ shows the structure of a c chain with the various numbers indicating the sites of the introduced N termini in the enzymes containing either the fragmented or the circularly permuted chains. The fragments encompassed the entire 310-amino-acid-residue c chain, and the circularly permuted chains involved linking residues 306 and 1.

Fig. 1.

Ribbon diagram of the three-dimensional structure of a catalytic chain of wild-type ATCase. The N-terminal domain (residues 1–134, in yellow) is on the left, and the C-terminal domain (residues 150–284, in blue) on the right. The two domains are linked by Helix 5, comprising residues 135–149 (in green). Helix 12, consisting of residues 285–305 (in red), crosses back from the C-terminal domain and interacts with residues in the N-terminal domain. The approximate positions of the cleaved polypeptide chains for the studies of the fragmented and circularly permuted c chains are indicated by an asterisk, and the numbers designate the locations of the newly introduced N termini.

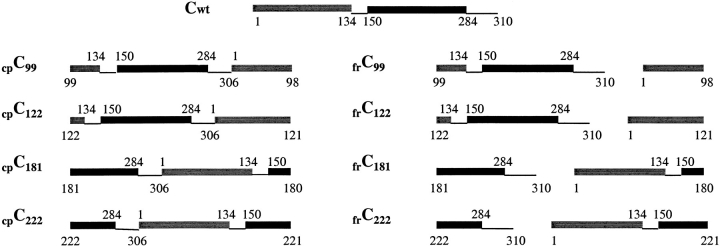

For the preparation of each ATCase variant, the pyrB gene was modified to produce the desired circularly permuted or fragmented gene needed for expression of the encoded cpc or frc chain. The plasmids also contained a modified pyrI gene (Graf and Schachman 1996), which encodes the r chain of ATCase containing a sequence tag of six His residues at the N terminus. In this way, fully assembled ATCase was produced in E. coli and readily purified. The amino acid sequences of the four different cpc and frc chains are illustrated schematically in Figure 2 ▶, which also shows how the continuity of the polypeptide chain within the two domains is disrupted.

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram illustrating the amino acid sequence of the N-terminal (gray square) and C-terminal (black square) domains in the wild-type c chain (cwt), fragmented c chains (frc), and circularly permuted chains (cpc). Numbers refer to the positions in the wild-type sequence. The region between residues 134 and 150 is Helix 5, and that between 284 and 305 is Helix 12, which is followed by a flexible pentapeptide terminating in the wild-type c chain at residue 310. In the enzyme containing fragmented c chains, the two fragments are arranged in the order of their expression in E. coli. For the enzyme containing the circularly permuted c chains, the last four residues were removed through appropriate truncation of the wild-type gene, thereby leading to a covalent linkage between residues 306 and 1.

(His)6 tag does not alter the allosteric properties of ATCase

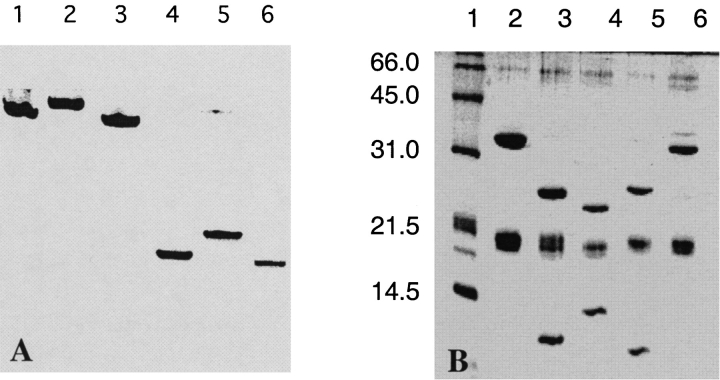

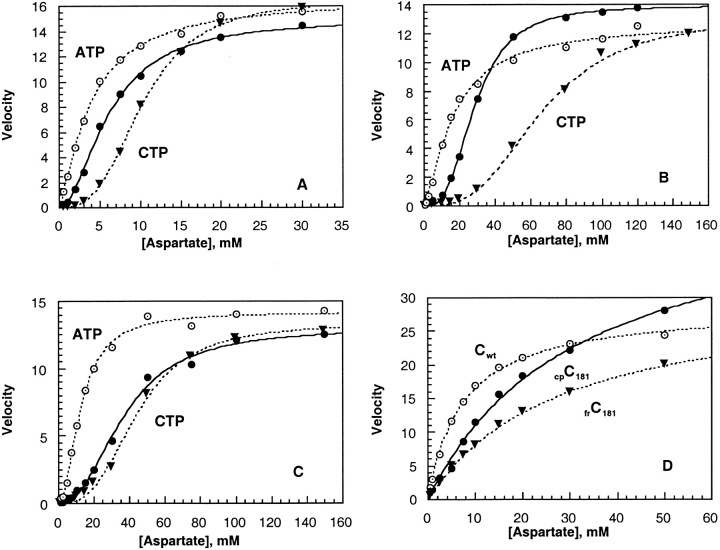

ATCase molecules containing a (His)6 tag inserted at the N terminus of the r chains (H6ATCasewt) were readily overexpressed and purified using a Q-Sepharose column followed by a Ni-NTA column (Graf and Schachman 1996). As shown in Figure 3 ▶A (lane 1), purified H6ATCasewt was detected as a single band by electrophoresis in polyacrylamide gels under nondenaturing conditions. In gels containing SDS, two major bands were detected Figure 3 ▶B (lane 2), which corresponded to molecular weights of 34 kD and 17 kD for the c and r chains, respectively. A minor band, corresponding to chains slightly smaller than 17 kD, was also detected; these shortened chains are probably attributable to the removal of the (His)6 tag in vivo. Enzyme assays (Fig. 4 ▶A) showed that H6ATCasewt retained the allosteric properties characteristic of the wild-type enzyme. The sigmoidal dependence of enzyme activity on the concentration of aspartate and the shifts in the saturation curves in the presence of the inhibitor, CTP, and the activator, ATP, as indicated by the kinetic parameters, K0.5, Vmax, and nH, were virtually identical to those exhibited by ATCasewt. In addition, the 2.7% decrease in the sedimentation coefficient of H6ATCasewt upon the addition of the bisubstrate ligand N-(phosphonacetyl)-l-aspartate (PALA) was very similar to that for ATCasewt.

Fig. 3.

Detection and characterization of ATCase variants and C trimers by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. (A) Electrophoresis under nondenaturing conditions was performed in 7% polyacrylamide gels stained for protein using Coomassie brilliant blue G250. (Lane 1) H6ATCasewt; (Lane 2) cpATCasec181; (Lane 3) frATCasec181; (Lane 4) Cwt; (Lane 5) cpCc181; and (Lane 6) frCc181. (B) Characterization of polypeptide chains and fragments in ATCase variants by electrophoresis in polyacrylamide gels containing SDS. (Lane 1) Protein molecular weight markers (lysozyme, 14.4 kD; soybean trypsin inhibitor, 21.5 kD; carbonic anhydrase, 31.0 kD; ovalbumin, 45.0 kD; bovine serum albumin, 66.2 kD); (Lane 2) H6ATCasewt; (Lane 3) frATCasec99; (Lane 4) frATCasec122; (Lane 5) frATCasec122; (Lane 6) cpATCasec99.

Fig. 4.

Enzyme activity of holoenzymes and C trimers containing fragmented and circularly permuted c chains. Assays were performed at 30°C with saturating [14C]carbamoyl phosphate (5 mM) in 50 mM MOPS buffer at pH 7.0, containing 0.2 mM EDTA and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol. Results are given in the absence of effectors (black circle), in the presence of 2mM ATP (hollow circle), and in the presence of 0.5 mM CTP (black triangle). Enzyme activities are expressed as velocity in micromoles of carbamoyl-l-aspartate formed per hour per microgram of C trimer as a function of the concentration of aspartate. (A) H6ATCasewt; (B) frATCasec181; (C) cpATCasec181; (D) Trimers Cwt; frCc181; and cpCc181.

A single endotherm with a Tm of 65°C was observed for H6ATCasewt, whereas ATCasewt exhibits two overlapping, relatively sharp transitions at 64°C and 68°C (Zhang and Schachman 1996). Upon the addition of excess PALA, the endotherm showed overlapping transitions at 65°C and 70°C for H6ATCasewt. These results indicate that the (His)6 tag at the N terminus of the r chain has little effect on the properties of the enzyme.

As expected, C trimers isolated from H6ATCasewt were very similar to trimers obtained from the wild-type enzyme. Gel electrophoresis under denaturing conditions (SDS-PAGE) showed a single band with a mobility corresponding to a 34-kD polypeptide.

Fragmented c chains assemble into stable ATCase-like oligomers

Both sedimentation velocity and electrophoresis experiments demonstrated that the four different sets of polypeptide fragments illustrated in Figure 2 ▶ were incorporated along with r chains into ATCase-like oligomers. The sedimentation coefficients of all four ATCase variants were 11.7 S. Moreover, the decrease in sedimentation coefficient (Δs/s ) resulting from the binding of PALA was about 2.6% (Table 1). Thus the assembled enzymes undergo the ligand-promoted global conformational change characteristic of wild-type ATCase (Howlett and Schachman 1977).

Table 1.

Properties of ATCase variantsa

| Vmax | K0.5 or Km | nH | Δs/sb | Tmc | |||||||

| Variant | ATP | — | CTp | ATP | — | CTP | ATP | — | CTP | (%) | (°C) |

| ATCasewtd | 16 | 15 | 14 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 2.2 | −2.6 | 64 68 |

| H6ATCasewt | 16 | 15 | 16 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 2.9 | −2.7 | 65 |

| frATCasec99 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 17 | 30 | 53 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 2.4 | −1.7 | 62 |

| cpATCasec99 | 13 | 12 | 13 | 18 | 32 | 40 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | −2.1 | 63 |

| frATCasec122 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 4 | 7 | 11 | 1.4 | 2.2 | 2.9 | −3.0 | 62 |

| cpATCasec122 | 18 | 16 | 18 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 2.9 | −2.6 | 63 |

| frATCasec181 | 12 | 14 | 12 | 15 | 29 | 60 | 1.5 | 2.9 | 3.5 | −2.2 | 63 |

| cpATCasec181 | 14 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 37 | 44 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.9 | −3.2 | 65 |

| frATCasec222 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 14 | 23 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 2.4 | −2.5 | 64 |

| cpATCasec222 | 21 | 21 | 20 | 11 | 17 | 26 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 2.6 | −2.2 | 63 |

| Cwt | 27 | 6 | NDe | ||||||||

| frC181 | 31 | 28 | NDe | ||||||||

| cpC181 | 34 | 23 | NDe | ||||||||

a Kinetics were performed at 30°C with saturating [14C]carbamoyl phosphate (5 mM) and varying concentrations of aspartate in 50 mM MOPS buffer, pH 7.0, containing 0.2 mM EDTA, and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol. Values of Vmax are in units of μmole carbamoyl aspartate per μg of C trimer per h. K0.5 is the concentration of aspartate (mM), corresponding to 0.5 Vmax. The concentrations of the allosteric effectors ATP and CTP were 2 mM and 0.5 mM, respectively. Hill coefficients, nH, were evaluated from a fit of the assay data according to Hill equation using the program KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software).

b The effect of PALA on the sedimentation coefficient is expressed as Δs/s in %. Measurements of the enzyme in the absence and presence of PALA were made with a Beckman model XL-A analytical ultracentrifuge at 20°C at concentrations of 1.5 mg/mL in 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, containing 0.1 M NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol.

c Values of Tm were measured using a Microcal MC-2 calorimeter. Samples contained proteins at 0.4 mg/mL in 40 mM potassium borate at pH 9.0 containing 0.2 mM EDTA and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol.

d See reference (Zhang and Schachman 1996).

e ND, not determined.

Purified frATCasec181 exhibited a single band upon electrophoresis in polyacrylamide gels under nondenaturing conditions (Fig. 3 ▶A, lane 3) with a mobility slightly larger than that of H6ATCasewt. The other three fragmented ATCase variants (frATCasec99, frATCasec122, and frATCasec222) had identical or very similar mobilities to wild-type enzyme under nondenaturing conditions (data not shown). Differential scanning calorimetry showed that the four ATCase variants containing fragmented c chains had values of Tm comparable to that of the wild-type enzyme (Table 1). A single endotherm with a Tm of 63°C was observed for frATCasec181. The Tm increased to 66°C and 70°C in the presence of 20- and 100-fold molar excess of PALA, respectively.

Electrophoresis under denaturing conditions was used to demonstrate that the c chains in the various oligomers were fragmented and that the sizes of the constituent polypeptides were compatible with the DNA constructs used for their expression. The patterns from SDS-PAGE experiments are illustrated in Figure 3 ▶B. The two major polypeptides from H6ATCasewt (lane 2), representing intact c chains and His-tagged r chains, have values of Mr corresponding to molecular weights of 34 kD and 17 kD, respectively. A minor band was observed in many SDS-PAGE experiments and is probably attributable to the in vivo removal of the His tag. Lanes 3, 4, and 5 in Figure 3 ▶B show the polypeptide fragments in frATCasec99, frATCasec122, and frATCasec222, respectively. Each pattern shows a prominent band corresponding to the His-tag r chain with a minor satellite band representing a slightly smaller polypeptide. The other two bands in each pattern represent the polypeptide fragments encoded by the fragmented pyrB gene, and the mobilities were consistent with the molecular weights expected based on the DNA sequences. Mobilities of the fragments from frATCasec99 correspond to a 23-kD polypeptide representing the C-terminal region of the chain and the 11-kD polypeptide derived from the N terminus, whereas the 24-kD and 10-kD fragments from frATCasec222 represent the N- and C-terminal peptides. The 22-kD and 13-kD fragments from frATCasec122 correspond to the C- and N-terminal peptide fragments. The polypeptide fragments were isolated by reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatography and analyzed by electron spray mass spectrometry for molecular weight determinations. For fragment 1–180 the measured molecular weight was 19,516.2, a value very close to the calculated value of 19,517.1 (assuming the removal of the N-terminal Met residue). Mass spectrometric analysis for fragment 181–310 yielded 14,929.2 and 14,798.1, which are identical to the values 14,929.2 and 14,798.1 calculated for the fragment with and without an N-terminal Met residue. Approximately one-third of the fragments had the N-terminal Met residue and about two-thirds of the polypeptide fragments lacked that residue. The measured molecular weights of the polypeptide fragments of the c chains of frATCasec99 and frATCasec122 were virtually identical to the values calculated from the amino acid sequence with the assumption that the N-terminal Met residue was removed in vivo.

The C trimer containing the fragmented c chains was isolated from frATCasec181 by treatment of the holoenzyme with a mercurial (Yang et al. 1978). As seen in Figure 3 ▶A (lane 6), gel electrophoresis experiments under nondenaturing conditions revealed a single band for frCc181 with a mobility similar to that for Cwt. In SDS-PAGE experiments on frCc181, two bands were detected corresponding to molecular weights of 20 kD and 15 kD.

Although frCc181 trimers tended to aggregate, thereby limiting physical studies on them, assays of enzyme activity showed that Vmax and Km for aspartate were 31 μmole/μg per hour and 28 mM, compared to 27 μmole/μg per hour and 6 mM for Cwt, respectively. Fragmented c chains (frcCc181) were also expressed in E. coli lacking the pyrI gene, resulting in the formation of active frCc181 trimers (data not shown). The C trimers from the other variants containing fragmented c chains were insoluble, precluding measurements of enzyme activity or physical properties.

ATCase variants containing fragmented c chains are active and allosteric

The activity of frATCasec181 was comparable to that of H6ATCasewt, with values for Vmax of 14 and 15 μmole/μg per hour, respectively. However, as seen by comparing Figures 4A and 4B ▶, the value of K0.5 for aspartate for frATCasec181 is about 5 times larger than that for H6ATCasewt. Figure 4 ▶C shows that K0.5 for the enzyme containing circularly permuted c chains, cpATCasec181, is also increased markedly compared to the wild-type enzyme. This change in affinity for aspartate caused by the introduction of new N and C termini is demonstrated clearly by the results for the C trimers shown in Figure 4 ▶D. Results for the holoenzymes, summarized in Table 1, show that nH for frATCasec181 is 2.9, compared to 1.6 for H6ATCasewt. Shifts in the sigmoidal saturation curve for frATCasec181 upon the addition of heterotropic effectors are illustrated in Figure 4 ▶B, which shows that the value of K0.5 changed from 29 mM aspartate to 15 mM upon the addition of ATP and to 60 mM in the presence of CTP. Comparable shifts in aspartate saturation curves for H6ATCasewt are illustrated in Figure 4 ▶A.

These results along with analogous observations (Table 1) for frATCasec99, frATCasec122, and frATCasec222 demonstrate that ATCase molecules containing c chains fragmented in different regions of the structure exhibit homotropic and heterotropic properties characteristic of wild-type enzyme. Table 1 also summarizes the results for the four ATCase variants containing circularly permuted c chains. Two of these variants, cpATCasec122 and cpATCasec222, had been prepared earlier (Zhang and Schachman 1996) using a different technique for generating the permuted c chains. Except for the values of Vmax, the results for the variants containing fragmented and circularly permuted c chains were similar. Values of Vmax are known to vary because of storage of the enzymes and the use of different substrate preparations; hence it is difficult to attach significance to those variations. The results in Table 1 demonstrate that the ATCase variants containing fragmented and/or circularly permuted c chains are very similar in their allosteric properties, their thermal stability, and in the PALA-promoted change in quaternary structure.

Discussion

The four ATCase variants containing fragmented c chains exhibited homotropic and heterotropic effects, as well as thermal stabilities, similar to those of the wild-type enzyme (Table 1). These results indicate that a lack of continuity in the polypeptide chain is readily tolerated as long as the interruption is located in a noncritical region of the structure. In earlier studies (Powers et al. 1993; Yang and Schachman 1993b), it was found that the holoenzyme containing fragmented c chains cleaved in the 240s loop lacked allosteric properties. Residues in that loop are involved in interactions between the two C trimers when the enzyme is in the T state, and that region undergoes a large conformational change upon the binding of PALA to the enzyme (Lipscomb 1994). Hence, connectivity in that region of the polypeptide chain is probably essential for stabilizing the enzyme in the compact, taut state. It is striking that all of the ATCase variants summarized in Table 1 exhibit allosteric properties despite the interruption of the polypeptide chain in either domain and in diverse regions of the structure. For three of the variants, frATCasec99, frATCasec122, and frATCasec222, the cleavage of the chain occurs in regions that are largely buried in the wild-type enzyme. In frATCasec181, the disruption is in a region involving chain–chain interactions in the same trimer and some contacts with other segments of the main chain. The similarity in behavior of the analogous variants containing fragmented or circularly permuted c chains indicates that not only are the introduction of new N and C termini tolerated readily, but also that the linkage of the wild-type terminal regions does not interfere with the conformational change essential for allostery. Although the allosteric properties of the variants were not significantly altered by the introduction of newly charged termini in the different domains, the values of K0.5 were affected. It is noteworthy that the substantial increases in K0.5 are almost identical for the holoenzymes containing either the fragmented or the circularly permuted chains (Table 1). These increases, based on the comparable findings for the nonallosteric C trimers (Fig. 4 ▶D), are attributable to a decreased affinity for the substate, aspartate. Speculations regarding explanations for these increases in K0.5 are unwarranted until evidence is available about possible structural changes resulting from the enhanced flexibility of the chains and the presence of new ion pairs.

Many proteins composed of circularly permuted polypeptide chains have slightly lower thermal stabilities than their wild-type counterparts (Buchwalder et al. 1992; Yang and Schachman 1993a; Zhang et al. 1993; Vignais et al. 1995; Garrett et al. 1996; Zhang and Schachman 1996; Pieper et al. 1997; Hennecke et al. 1999). Interpreting the decreased thermal stability of circularly permuted variants is hazardous because of the possible constraint introduced by linkage of the original termini, the introduction of flexibility in the vicinity of the new N and C termini, and possible structural changes resulting from these charged residues. For ATCase, values of Tm for the holoenzyme containing either circularly permuted or fragmented c chains are similar and only slightly lower than that of wild-type enzyme (Table 1). The comparison between the two types of variants provides evidence to support the conclusion that linkage of the original terminal regions does not cause significant destabilization of the structure.

Domains in proteins are generally considered as important folding units along the pathway of assembly of multidomain proteins, and it is frequently assumed that folding of chains is contemporaneous with synthesis of the polypeptides. The formation of a stable domain from a continuous polypeptide chain would involve a folding process based on unimolecular reactions. When the continuity of the polypeptide chain within the domains is disrupted, as in the variants described here, the formation of the domains must involve a bimolecular process. The experiments on frATCasec181 were particularly interesting because active frCc181 trimers were isolated readily by dissociation of the holoenzyme, and independently these trimers were formed in vivo upon expression of the fragmented pyrB gene in the absence of pyrI. Clearly the fragments, 1–180 and 181–310, must fold sufficiently into secondary and tertiary structures for recognition and docking by bimolecular reactions. The discontinuous chain containing the folded domain then oligomerizes to give trimers, which then associate with regulatory dimers to form stable, active holoenzymes exhibiting the allosteric properties of wild-type ATCase. Complementation between fragments that comprise structurally recognizable domains in the c chains of ATCase appears to be very efficient, and physical chemical studies with isolated fragments are necessary for a more detailed understanding of the individual reactions in the assembly process.

Materials and methods

Plasmid construction

The starting material for the construction of a fragmented or a circularly permuted c chain of ATCase was plasmid PAX4 containing the pyrB and pyrI genes, which encode the c and r chain of ATCase, respectively. A coding region was incorporated for the insertion of a (His)6-tag sequence at the N terminus of the r chain. NcoI and HindIII restriction sites were incorporated at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the pyrB gene, respectively, and ribosome-binding sequences were placed at the 5′ end of pyrB and pyrI. The PAX4 vector was first modified by changing the NcoI and the HindIII sites into NdeI and BamHI sites, respectively, using PCR to give the modified vector PAX4a. The DNA sequence encoding the fragmented or the circularly permuted c chain was prepared by a method using three primers for PCR.

For the preparation of pyrBcp181 and pyrBfr181, Primer P1 was an oligonucleotide coding for residue 181–187 with an NdeI site in the 5′ end. Primer P2 was an oligonucleotide whose complementary sequence encodes for the residue 174–180 with a BamHI site and a stop codon in the 5' end. Primer P3a for the circular permutation mutant was a 42-mer oligonucleotide coding for the residues 300–306 and 1–7 in the sense direction. The Primers 1 and 2 for the expression of the fragmented c chain were the same as those used in the preparation of the circularly permuted gene. The third primer P3b was also a 42-mer oligonucleotide containing the coding sequence for residue 1–7 and part of the sequence between the stop codon of pyrB and the start codon of pyrI in PAX4. The PCR reactions were carried out under standard conditions with solutions containing 4 mM MgCl2, 1× Taq polymerase buffer, 0.2 mM each dNTP, 0.2 mM primer P1 and P2, 0.01 mM primer P3, and 1 unit of Taq polymerase. The PCR products were digested with NdeI and BamHI and then ligated to PAX4a digested with the same pair of enzymes. Gene sequences were confirmed by sequencing using ABI 100.

Expression and purification of ATCase variants

The plasmid containing the pyrBcp and pyrI genes was transformed into E. coli HS533 cells. The plasmid containing the pyrBfr and pyrI genes was transformed into either E. coli BL21 or E. coli HS533 cells harboring pGP1–2 (Tabor and Richardson 1985). Escherichia coli HS533 cells carrying pyrBcp were grown at 37°C in LB media containing 50 mg/L of ampicillin for 24 h. Transformed E. coli BL21 cells carrying pryBfr were grown in LB media containing 50 mg/mL of ampicillin at 37°C, followed by the addition of IPTG and continued incubation for 4–8 h.

The ATCase mutants were purified by procedures used routinely in this laboratory. Catalytic trimers of wild-type and mutant ATCases were prepared from holoenzyme by treating the enzyme with neohydrin and separating the subunits as described (Yang et al. 1978).

Other procedures

Enzyme activity was measured with 14C-labeled carbamoyl phosphate (New England Nuclear) as described (Davies et al. 1970). Assays were performed at 30°C in 50 mM MOPS at pH 7.0, containing 0.2 mM EDTA and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol with saturated carbamoyl phosphate and variable concentration of aspartate. Then 2 mM ATP and 0.5 mM CTP were used to examine the effects of nucleotides with buffer above containing 3 mM Mg(OAc)2. Assay data were analyzed in terms of the Hill equation using the program KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software).

A Beckman Model XL-A Analytical Ultracentrifuge equipped with absorption optics was used to measure the change in sedimentation coefficient (Δs/s) of the enzyme caused by the binding of PALA. The protein concentration was 1.5 mg/mL in buffer A containing 0.1 M KCl. The ratio of PALA per active site of ATCase is 2.5 : 1 for wild type and 20 : 1 for the variants.

Differential scanning microcalorimetry was performed using the Microcal MC-2 calorimeter as described (Peterson and Schachman 1991). The protein concentration was 0.4 mg/mL in 40 mM potassium borate buffer at pH 9.0 containing 0.2 mM EDTA.

Nondenaturing PAGE was performed as described (Jovin et al. 1964), using 7% polyacrylamide gel. The gel was stained for total protein by Coomassie blue or for activity using 2 mM carbamoyl phosphate and 100 mM aspartate as described (Bothwell 1975). SDS-PAGE was performed on 17.5% polyacrylamide gel followed by staining with Coomassie blue.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences research grant GM 12159. We are indebted to Ying R. Yang for her help and valuable suggestions during the course of this work. We thank Dr. David King of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of California at Berkeley, for determining the molecular weights of the polypeptide chains by mass spectrometry.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges.This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Abbreviations

ATCase, aspartate transcarbamoylase

C, catalytic trimer or subunit

c, catalytic polypeptide chain

R, regulatory dimer or subunit

r, regulatory polypeptide chain

wt as subscript, wild type

fr as subscript, fragmented polypeptide chain

cp as subscript, circularly permuted

c and number following it in subscript designate the position of the amino acid residue in the wild-type catalytic chain at which the new N terminus in the fragmented or circularly permuted chain is located

H6 as subscript, hexa-His sequence at the N terminus of the regulatory chain

MOPS, 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid

PAGE, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

SDS-PAGE, sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

PCR, polymerase chain reaction

PALA, N-(phosphonacetyl)-l-aspartate

Tm, melting temperature corresponding to the maximum temperature in the endotherm obtained by differential scanning microcalorimetry

Article and publication are at www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.38901.

References

- Beernink, P.T., Yang, Y.R., Graf, R., King, D.S., Shah, S.S., and Schachman, H.K. 2001. Random circular permutation leading to chain disruption within and near α helices in the catalytic chains of aspartate transcarbamoylase: Effects on assembly, stability, and function. Protein Sci. 10 528–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bothwell, M.A. 1975. "Kinetics and thermodynamics of subunit interactions in aspartate transcarbamylase. " PhD thesis, University of California, Berkeley.

- Buchwalder, A., Szadkowski, H., and Kirschner, K. 1992. A fully active variant of dihydrofolate reductase with a circularly permuted sequence. Biochemistry 31 1621–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu, V., Freitag, S., Le Trong, I., Stenkamp, R., and Stayton, P. 1998. Thermodynamic and structural consequences of flexible loop deletion by circular permutation in the streptavidin–biotin system. Protein Sci. 7 848–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, G.E., Vanaman, T.C., and Stark, G.R. 1970. Aspartate transcarbamylase. Stereospecific restrictions on the binding site for l-aspartate. J. Biol. Chem. 245 1175–1179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y., Minnerly, J., Zurfluh, L., Joy, W., Hood, W., Abegg, A., Grabbe, E., Shieh, J., Thurman, T., McKearn, J., et al. 1999. Circular permutation of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Biochemistry 38 4553–4563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, A. and Taniuchi, H. 1992. A study of core domains, and the core domain–domain interaction of cytochrome c fragment complex. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 296 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galakatos, N. and Walsh, C. 1987. Specific proteolysis of native alanine racemases from Salmonella typhimurium: Identification of the cleavage site and characterization of the clipped two-domain proteins. Biochemistry 26 8475–8480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, J.B., Mullins, L.S., and Raushel, F.M. 1996. Are turns required for the folding of ribonuclease T1? Protein Sci. 5 204–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg, D.P. and Creighton, T.E. 1983. Circular and circularly permuted forms of bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor. J. Mol. Biol. 165 407–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf, R. and Schachman, H.K. 1996. Random circular permutation of genes and expressed polypeptide chains: Application of the method to the catalytic chains of aspartate transcarbamoylase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93 11591–11596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, M., Piotukh, K., Borriss, R., and Heinemann, U. 1994. Native-like in vivo folding of a circularly permuted jellyroll protein shown by crystal structure analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91 10417–10421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath, R.H. 1994. "The global conformation determines the functional properties of the ligand sites of aspartate transcarbamoylase. " PhD thesis, University of California, Berkeley.

- Heinemann, U. and Hahn, M. 1995. Circular permutations of protein sequence: Not so rare? Trends Biochem. Sci. 20 349–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennecke, J., Sebbel, P., and Glockshuber, R. 1999. Random circular permutation of DsbA reveals segments that are essential for protein folding and stability. J. Mol. Biol. 286 1197–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren, A. and Slabay, I. 1979. Thioredoxin-C`: Mechanism of noncovalent complementation and reactions of the refolded complex and the active site containing fragment with thioredoxin reductase. Biochemistry 18 5591–5599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honzatko, R.B. and Lipscomb, W.N. 1982. Interactions of phosphate ligands with Escherichia coli aspartate carbamoyltransferase in the crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 160 265–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horlick, R.A., George, H.J., Cooke, G.M., Tritch, R.J., Newton, R.C., Dwivedi, A., Lischwe, M., Salemme, F.R., Weber, P.C., and Horuk, R. 1992. Permuteins of interleukin 1β—A simplified approach for the construction of permutated proteins having new termini. Protein Eng. 5 427–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlett, G.J. and Schachman, H.K. 1977. Allosteric regulation of aspartate transcarbamoylase. Changes in the sedimentation coefficient promoted by the bisubstrate analogue N-(phosphonacetyl)-l-aspartate. Biochemistry 16 5077–5083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovin, T., Chrambach, A., and Naughton, M.A. 1964. An apparatus for preparative temperature-regulated polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Anal. Biochem. 9 351–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke, H., Lipscomb, W.N., Cho, Y., and Honzatko, R.B. 1988. Complex of N-phosphonacetyl-l-aspartate with aspartate carbamoyltransferase. X-Ray refinement, analysis of conformational changes and catalytic and allosteric mechanisms. J. Mol. Biol. 204 725–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.H., Pan, Z., Honzatko, R.B., Ke, H.-M., and Lipscomb, W.N. 1987. Structural asymmetry in the CTP-liganded form of aspartate carbamoyltransferase from Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 196 853–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kippen, A., Sancho, J., and Fersht, A. 1994. Folding of barnase in parts. Biochemistry 33 3778–3786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreitman, R.J., Puri, R.K., and Pastan, I. 1994. A circularly permuted recombinant interleukin 4 toxin with increased activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91 6889–6893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, C. and Bewley, T. 1976. Human pituitary growth hormone: Restoration of full biological activity by noncovalent interaction of two fragments of the hormone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 73 1476–1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb, W.N. 1994. Aspartate transcarbamylase from Escherichia coli: activity and regulation. Adv. Enzymol. 68 67–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minard, P., Hall, L., Betton, J., Missiakas, D., and Yon, J. 1989. Efficient expression and characterization of isolated structural domains of yeast phosphoglycerate kinase generated by site-directed mutagenesis. Protein Eng. 3 55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, L.S., Wesseling, K., Kuo, J.M., Garrett, J.B., and Raushel, F.M. 1994. Transposition of protein sequences: Circular permutation of ribonuclease T1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116 5529–5533. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, T. and Iwakura, M. 1999. Circular permutation analysis as a method for distinction of functional elements in the M20 loop of Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 274 19041–19047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otzen, D. and Fersht, A. 1998. Folding of circular and permuted chymotrypsin inhibitor 2: Retention of the folding nucleus. Biochemistry 37 8139–8146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, C.B. and Schachman, H.K. 1991. Role of a carboxyl-terminal helix in the assembly, interchain interactions, and stability of aspartate transcarbamoylase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88 458–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieper, U., Hayakawa, K., Li, Z., and Herzberg, O. 1997. Circularly permuted β-lactamase from Staphylococcus aureus PC1. Biochemistry 36 8767–8774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers, V.M., Yang, Y.R., Fogli, M.J., and Schachman, H.K. 1993. Reconstitution of active catalytic trimer of aspartate transcarbamoylase from proteolytically cleaved polypeptide chains. Protein Sci. 2 1001–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Protasova, N.Y., Kireeva, M.L., Murzina, N.V., Murzin, A.G., Uversky, V.N., Gryaznova, O.I., and Gudkov, A.T. 1994. Circularly permuted dihydrofolate reductase of E. coli has functional activity and a destabilized tertiary structure. Protein Eng. 7 1373–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards, F.M. 1958. On the enzyme activity of subtilisin-modified ribonuclease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 44 162–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards, F.M. and Vithayathil, P.J. 1959. The preparation of subtilisin-modified ribonuclease and the separation of the peptide and protein components. J. Biol. Chem. 234 1459–1465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiba, K. and Schimmel, P. 1992. Functional assembly of a randomly cleaved protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89 1880–1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strittmatter, P., Barry, R., and Corcoran, D. 1972. Tryptic conversion of cytochrome b5 reductase to an active derivative containing two peptide chains. J. Biol. Chem. 247 2768–2775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabor, S. and Richardson, C.C. 1985. A bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase/promoter system for controlled exclusive expression of specific genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82 1074–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniuchi, H., Parker, D., and Bohnert, J. 1977. Study of equilibration of the system involving two alternative, enzymically active complementing structures simultaneously formed from two overlapping fragments of staphylococcal nuclease. J. Biol. Chem. 252 125–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniuchi, H., Parr, G. and Juillerat, M. 1986. Complementation in folding and fragment exchange. Methods Enzymol. 131 185–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasayco, M. and Carey, J. 1992. Ordered self-assembly of polypeptide fragments to form nativelike dimeric trp repressor. Science 255 594–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyama, H., Tanizawa, K., Yoshimura, T., Asano, S., Lim, Y., Esaki, N., and Soda, K. 1991. Thermostable alanine racemase of Bacillus stearothermophilus. Construction and expression of active fragmentary enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 266 13634–13639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji, T., Yoshida, K., Satoh, A., Kohno, T., Kobayashi, K., and Yanagawa, H. 1999. Foldability of barnase mutants obtained by permutation of modules or secondary structure units. J. Mol. Biol. 286 1581–1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uversky, V., Kutyshenko, V., Protasova, N., Rogov, V., Vassilenko, K., and Gudkov, A. 1996. Circularly permuted dihydrofolate reductase possesses all the properties of the molten globule state, but can resume functional tertiary structure by interaction with its ligands. Protein Sci.. 5 1844–1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignais, M.-L., Corbier, C., Mulliert, G., Branlant, C., and Branlant, G. 1995. Circular permutation within the coenzyme binding domain of the tetrameric glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from Bacillus stearothermophilus. Protein Sci. 4 994–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viguera, A.R., Blanco, F.J., and Serrano, L. 1995. The order of secondary structure elements does not determine the structure of a protein but does affect its folding kinetics. J. Mol. Biol. 247 670–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viguera, A., Serrano, L., and Wilmanns, M. 1996. Different folding transition states may result in the same native structure. Nat. Struct. Biol. 3 874–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright, G., Basak, A., Wieligmann, K., Mayr, E., and Slingsby, C. 1998. Circular permutation of βB2-crystallin changes the hierarchy of domain assembly. Protein Sci. 7 1280–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.R. and Schachman, H.K. 1993a. Aspartate transcarbamoylase containing circularly permuted catalytic polypeptide chains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90 11980–11984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1993b. In vivo formation of active aspartate transcarbamoylase from complementing fragments of the catalytic polypeptide chains. Protein Sci. 2 1013–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.R., Kirschner, M.W., and Schachman, H.K. 1978. Aspartate transcarbamoylase (Escherichia coli): Preparation of subunits. Methods Enzymol. 51 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P. and Schachman, H.K. 1996. In vivo formation of allosteric aspartate transcarbamoylase containing circularly permuted catalytic polypeptide chains: Implications for protein folding and assembly. Protein Sci. 5 1290–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T., Bertelsen, E., Benvegnu, D., and Alber, T. 1993. Circular permutation of T4 lysozyme. Biochemistry 32 12311–12318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]