Abstract

One of the key challenges in computational genomics is annotating coding genes and identification of regulatory RNAs in complete genomes. An attempt is made in this study which uses the regulatory RNA locations and their conserved flanking genes identified within the genomic backbone of template genome to search for similar RNA locations in query genomes. The search is based on recently reported coexistence of small RNAs and their conserved flanking genes in related genomes. Based on our study, 54 additional sRNA locations and functions of 96 uncharacterized genes are predicted in two draft genomes viz., Serratia marcesens Db1 and Yersinia enterocolitica 8081. Although most of the identified additional small RNA regions and their corresponding flanking genes are homologous in nature, the proposed anchoring technique could successfully identify four non-homologous small RNA regions in Y. enterocolitica genome also. The KEGG Orthology (KO) based automated functional predictions confirms the predicted functions of 65 flanking genes having defined KO numbers, out of the total 96 predictions made by this method. This coexistence based method shows more sensitivity than controlled vocabularies in locating orthologous gene pairs even in the absence of defined Orthology numbers. All functional predictions made by this study in Y. enterocolitica 8081 were confirmed by the recently published complete genome sequence and annotations. This study also reports the possible regions of gene rearrangements in these two genomes and further characterization of such RNA regions could shed more light on their possible role in genome evolution.

Keywords: functional annotation, sRNA, KO, KOBAS, Bio-ontology, flanking genes

Abbreviations

eca - Erwinia caratovora atroseptica, eco - Escherichia coli K12, sma - Serratia marcescens Db1, ye - Yersinia enterocolitica 8081, ypk - Yersinia pestis KIM, yps - Yersinia pseudotuberculosis Db1, KEGG - Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, KO - KEGG Orthology, KOBAS - KO Based Annotation System.

Background

Genome sequencing projects are exponentially adding complete genome sequence data to genome databases; but, the identification of functionally important regulatory regions and the rate of annotating functions to the coding genes still needs to improve due to lack of parallel experimental techniques. Massive accumulation of complete genome sequence data in public databases such as NCBI-GenBank creates an opportunity for comparative genomics based identification of functional annotations for draft sequences from known genomes using variety of data mining tools [1]. Initial functional characterizations of proteins were carried out with biochemical experiments, which can be extended by matching recently sequenced proteins/genes through computational studies [2]. Such theoretical functional annotations for the unknown query sequences are assigned based on the known characteristics of the reference set. Additionally functional annotations of proteins have also been attempted based on several other properties like, proteins sharing common domains connected via related multi domain proteins (super families); proteins in the same pathways [3], networks, or complexes; or protein complexes in their expression pattern [4] and proteins correlated in their phylogenetic profiles [5]. Though many sophisticated techniques are employed, the identification of homologous relationship is one of the powerful techniques for functional annotations of unknown proteins from known data [6]. A rough estimate shows that well over 80% of our biological knowledge concerning protein sequences is inferred from homology [7]. Availability of intermediate grade complete genome sequences (without functional characterization) opens up a prosperous way for comparative genomic analysis based annotations in related genomes [8]. This study uses two such draft genomes (at the time of initiating the work) for the functional annotations of proteins based on non-coding small RNA (sRNA) identification in prokaryotic genomes.

In recent years, non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) have been identified to have variety of regulatory functions. Most of the non-coding sRNAs are of intergenic origin [9,10]. Due to the lack of potent statistical signals their identification has become difficult [11,12]. The redundancy and co-occurrence of sRNAs sandwiched between a pair of conserved flanked genes in prokaryotic genomes is reported [10]. This feature has been used to identify both homologous and non-homologous additional sRNA locations in 20 closely related Enterobacteriaceae genomes [13]. The locus of such additional sRNA locations (ASLs) follows genomic backbone continuity and gene synteny (gene order) conservation. These results also confirm that all experimentally known sRNAs and the ASLs fall within the intergenic regions and follow the redundancy and co-occurrence of sRNAs sandwiched between a pair of conserved flanked genes rule, especially, in Enterobacteriaceae genomes. The current study uses the above principle to identify ASLs and functionally annotate their respective conserved flanking genes pair in two draft completed genomes viz., Serratia marcesens Db1 (sma) and Yersinia enterocolitica 8081 (ye). Preliminary gene prediction data reported as ORFs obtained from the respective genome sequencing groups of sma and ye in EMBL format [14] are analyzed and functional annotations of 96 such ORFs are presented. The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes Orthology (KO) system has been used to compare the above functional assignments. Throughout the text, KEGG annotations for genome names and gene ids are used for convenience.

Methodology

Identification of additional sRNA locations (ASLs)

The complete draft genome sequence data for sma and ye along with their primary gene predictions in EMBL format [14] are obtained from Sanger Centre [15,16]. The nucleotide sequences of 60 known sRNAs of E. coli K12 (eco) (NC_000913), termed as sRNA template sequences (STS), are extracted from Ecocyc [17] database. Similar to our earlier work [13], the eco STS are used to search for homologous ASLs in sma and ye genomes using genomic blast [18,19] maintained at Sanger centre with default parameters (Database: genome assembly, Executable: BLASTN, Filter: Low complexity regions and report: top 100 alignments). Blast hits showing >80% identity (cut-off) alone are considered as homologous ASLs. As reported in our earlier study, a few of the eco STS had to be replaced with other known STS obtained from eca or yps genomes to obtain better ASL homologs. This search resulted in the identification of 54 ASLs in both sma and ye genomes collectively.

Identification of homologous protein sequence locations (HPSLs) that sandwich ASLs in sma and ye

The protein sequences of the genes that sandwich the known 60 eco sRNAs are extracted from KEGG [20]. Using these extracted protein sequences as templates, a search for homologous protein sequence locations (HPSLs) in sma and ye draft genomes are marked using TBLASTN (with default parameters). Although, this resulted in few/several HPSLs in each of the selected draft genomes, HPSLs that sandwich the already identified 54 ASLs alone are considered for further studies.

Selection of preliminary ORFs and assignment of functional annotations

The preliminary gene ids for the ORFs in the draft genomes that either fall or overlap within the HPSLs sandwiching the ASLs alone are extracted. Functional annotations for these preliminary gene ids are assigned based on consensus gene functions reported for the flanking genes in eco and other related genomes using KEGG. The sRNA specific conserved flanking gene pairs in 20 Enterobacteriaceae genomes already reported [13] are used in this study.

Genomic backbone continuity of the regions of interest (identified regions)

Although, the identified ASLs and their conserved flanking genes are picked up for functional annotations based on sequence homology, our earlier studies indicates that the conserved nature of these regions are retained only if the query regions are observed to be within the common genomic backbone. Hence, a multiple genome sequence alignment for the eco, sma and ye genomes is made with Mauve [21] aligners under default parameters (default seed weight = 15, determine LCBs, full alignment mode, Extend LCBs, minimum island size = 50, maximum backbone gap size = 50 and minimum backbone size = 50). This alignment is used to verify the genomic backbone continuity of the identified regions.

Example

The STS of sRNA tke1 of eco extracted from Ecocyc [17] database is used to search against the query genome sma. Genomic blast is used to identify ASLs within the query genomes. The protein sequences of the genes yfhK (gene id1: b2556) and purL (gene id2: b2557) that sandwich tke1 sRNA in eco are also extracted from KEGG database. These protein sequences are used as template sequences for a similarity sequence search using TBLASTN with default parameters in sma. The BLAST search will result in identification of several HPSLs. However, a careful analysis is carried out to extract only HPSLs that sandwich the corresponding tke1 ASLs. The preliminary gene ids reported in the database for the ORFs located within the HPSLs sandwiching the tke1 ASLs alone are extracted. These extracted preliminary gene ids refer to the ORFs sma3041 and sma3042 in sma. The tke1 sRNA is already reported to be flanked by conserved yfhK/purL genes pair in sixteen enterobacterial genomes [13] and their gene ids are c3079/c3080 (ecc), ecs3422/ecs3423 in ecs, b2556/b2557 in eco, z3833/z3835 in ece, eca3257/eca3258 in eca, plu3313/plu3317 in plu, spa0302/spa0300 in spt, t0292/t0291 in stt, sty2811/sty2812 in sty, stm2564/stm2565 in stm, sf2603/sf2604 in sfl, s2775/s2776 in sfx, yptb2876/yptb2879 in yps, yp2541/yp2536 in ypm, ypo2916/ypo2921 in ype and y1313/y1309 in ypk. Similarly the corresponding tke1 ASL identified in sma is observed to be flanked by two ORFs sma3041/sma3042. These ORFs sma3041 and sma3042 are further analyzed based on their sequence homology, length, KO numbers (from KOBAS) and based on the results obtained, sma3041 is functionally annotated as a two component sensor protein (yfhK) and sma3042 is functionally annotated as phosphoribosyl formylglycinamidine synthase (purL).

Similarly, the ORFs ye1035 and ye1032 that sandwich the tke1 ASL identified in ye genome are also functionally annotated as two component sensor protein (yfthK) and phosphoribosyl formylglycinamidine synthase (purL) respectively. The multiple genome sequence alignment of this region comprising the identified tke1 ASLs flanked by sma3041 and sma3042 in sma with eco and ye using Mauve [21] is shown (Figure 1). It can be seen from the figure 1 that the common backbone for the block containing tke1 sRNA with gene ids b2556 and b2557 in eco (marked A) are conserved in both sma (marked B) and ye (marked C) genomes.

Figure 1.

A multiple sequence alignment of eco, sma and ye genomes using Mauve. (A) The tke1 sRNA and its conserved flanking genes (b2556 and b2557) in eco are observed in ‘A’ block. (B) The identified ASL and its corresponding flanking genes (sma3041 and sma3042) are observed to be retained in the common genomic backbone marked ‘B’ in sma genome. (C) The identified ASL and its corresponding flanking genes (ye1032 and ye1035) are also observed to be retained in the common genomic backbone marked ‘C’ in ye genome.

Results

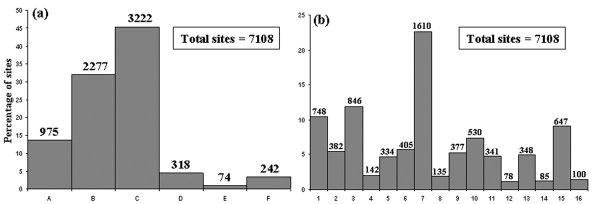

The combined results of the BLAST and TBLASTN as described above could identify 54 ASLs with their corresponding preliminary gene ids for the ORFs falling within sma and ye. The results are tabulated (Table 1a and Table 1b in supplementary material). The table lists known sRNAs selected, the coordinates of ASLs identified in sma and ye genomes, their strand orientations, the reference genome from which STS are extracted for the search and the identified preliminary flanking gene ids. Based on consensus functions reported for the conserved flanking genes on either side of the known sRNAs, in closely related enterobacterial genomes, the functional annotations for 96 id-affixed genes as described above are affixed and tabulated (Table 2a and Table 2b under supplementary material). These results also include the percentage of sequence identity and similarity of the id-affixed genes with their template protein sequences used. A perusal of the table indicates that most of the functionally annotated gene ids (except for a few) have high percentage of sequence identity and sequence similarity, indicating the high homologous nature between the template regions and the identified regions. The results obtained using KOBAS are also presented in this table.

A comparison of functional annotations using KO terms

KEGG Orthology (KO) terms or numbers are used to differentiate the universe of all genes in all organisms available in the KEGG database into groups of functionally identical genes (orthologs). KO based automated functional prediction systems is a specialized ontology system developed more specifically for prokaryotic annotations. The recently described KO based annotation system (KOBAS) [22] is used to annotate the unknown query (protein) sequences. In order to compare the functional annotations made from this study, the functional annotations of the preliminary gene ids using KO terms are also obtained as described below. The nucleotide sequences of all the identified preliminary gene ids from sma and ye are extracted using the Emboss extractseq code obtained from Embosswin [23] 2.10.0.-win-0.8 [24]. Strand orientations of the sequences in complement strand are reversed using revseq application. The extracted sequences of all these genes with their exact strand orientations (+ or − strand) in fasta format is given as input for KOBAS an automated functional analysis program. The results of KOBAS will contain a major orthologous gene id, obtained from KEGG-GENES [20] database, and is considered as a functionally equivalent gene to that of the selected gene id. The KOBAS will assign the KO number under which the gene/protein function grouped. Based on the KO terms, the functions of the specific gene id can be assigned. These KO based functional annotations are used to compare the functional predictions made from the current study.

These KO number under which the identified gene id is grouped with its major orthologous hit (top hit by KOBAS) from KEGG-GENES database is presented. Based on the KO number, the functional annotation of the orthologous group under which the identified gene id is classified is also presented. Since sma and ye are only draft genomes, the KEGG database is yet to add KO terms for all the preliminary predicted gene ids. The latest version of KEGG database contains only 8032 KO terms and any further additions to this database for the sma and ye genomes can be used for more confirmations of functional annotations. In the absence of a KO term for a specific gene, KOBAS cannot assign its orthologous group and its function. Hence, only 65 functional annotations alone are presented in the table using KOBAS. All the functional predictions made from this study in Y. enterocolitica 8081 are confirmed by the recently published complete genome sequence and annotations [25].

Identification of non-homologous ASLs using conserved flanking genes in sma and ye

The STS of sRNAs rygC, ryeF, sroC and sroE could not identify any ASLs in sma and ye based on sequence search indicating that the sequences of these sRNAs are non-homologous. However, using the protein sequences that sandwich these sRNAs (rygC, ryeF, sroC and sroE) from eco as template sequences, a search for HPSLs in sma and ye is made. Since the genomic backbones within these regions are continuous, an attempt has been made to identify the ASLs in this genome. Table 3 (see supplementary material) gives the preliminary gene ids of the conserved flanking genes that could sandwich the listed sRNA whose sequences are non-homologous. Such non-homologous sRNA regions containing conserved flanking genes have already been reported for 21 different classes of enterobacterial small RNAs [13] within the members of the Enterobacteriaceae family. Computational approaches like INFERNAL (Rfam) and experimental reports propose these regions as corresponding sRNA locations even in the absence of sequence homology. Hence, for example, we propose that rygC sRNA is possible between the conserved flanking genes pair ye3399 and ye3400 in ye genome, whose sequences are non-homologous to any of the STS obtained from eco, eca, yps, etc.

Significance of this method

The above mentioned sRNA based anchoring or coexistence methodology employs simple nucleotide and protein sequence similarity searches along with the knowledge of genomic backbone continuity information towards identification of the functionally important regions. Although the blast searches for the draft genomes will produce redundant similarity hits, the current anchoring of ASLs could effectively identify both the ASLs and their corresponding conserved flanking genes with their functions. This study attempts to link known RNA data, flanking gene conservation and backbone retention to identify the gene functions in draft genomes.

Discussion

The occurrence of ASLs with conserved flanking genes in sma and ye indicate that the sRNAs are retained within the conserved flanking genes in related genomes. Only 27 ASLs could be identified from the known 60 STS in each of the sma and ye genomes. This could be probably because of the retention capacity of specific regions (sRNAs with their corresponding flanking genes) between different genuses within the family varies. If the common backbone is retained, the retention capacities of these regions are high. A few of the ASLs are observed to contain a single conserved flanking gene (marked * in Table 1a and Table 1b in supplementary material). However, the ASLs of these regions are confirmed based on high homologous nature of the STS. This suggests that intergenic regions containing non-coding transcripts may possibly involve in genome shuffling and gene rearrangements. Such ASLs containing a single conserved flanking gene has been reported as possible integration sites for ‘alien’ genetic pools [26].

Identification of four non-homologous ASLs based on orthologous flanking gene pairs (Table 3 under supplementary material) in the query genomes is based on an earlier study [13] that enterobacterial small RNAs are identified to have entirely distinct non-homologous sequences but with non-homologous orthologues. The KO term identification agrees with our functional annotation results for 65 preliminary gene ids. The current anchoring of ASLs to functionally annotate preliminary gene ids could succeed in annotating 96 genes indicating a clear advantage of the anchoring technique compared to other existing ontology based methods. It must be emphasized here that a few of the identified ASLs have already been computationally predicted as small ORF's in the draft genomes. These small ORF having distinct transcription signals must be sRNAs and they cannot be coding genes. Similar anchoring technique involving flanking genes or specific operon or gene cluster based RNA predictions may evolve as a new method for locating sRNAs in closely related genomes. Similar applications for the identification of ncRNAs, conserved flanking genes and their functional annotations in closely related Archaebacteria and Eukaryotes are also being attempted.

Conclusion

Functional annotations for coding genes and sRNA predictions in ongoing genome projects can be done with genomic backbone retention information obtained from related genomes. Although this work has been started much earlier, all the functional predictions made by this study have been confirmed by the recently published complete genome sequence and annotations for Y. enterocolitica 8081 [NCBI-Refseq Accession number NC_008800]. The above study also indicates the possible identification of non-homologous sRNA regions even in the absence of sequence similarity. Identification of sRNAs with a single conserved flanking gene has been proposed to be regions of ‘alien’ gene pool integration sites. Characterization of these sRNA regions involved with foreign gene integration and such ‘alien’ genetic pool may elucidate their role in pathogenesis and survival of the pathogen.

Supplementary material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Govt. of India New Delhi for funding the “Centre of Excellence in Bioinformatics”. One of the authors, JS thanks the DBT for research fellowship. We acknowledge the Sanger Institute for the use of ‘sma’ and ‘ye’ draft genome data.

References

- 1.Nandi T, et al. J Biosci. 2002;27:15. doi: 10.1007/BF02703680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bork P, et al. J Mol Biol. 1998;283:707. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zheng Y, et al. Genome Biol. 2002;3:0060. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-11-research0060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Attwood TK. Brief Bioinformatics. 2000;1:45. doi: 10.1093/bib/1.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcotte EM, et al. Nature. 1999;402:83. doi: 10.1038/47048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stein L. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:493. doi: 10.1038/35080529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.George DG. Meth Enzymol. 1996;266:41. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)66005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blakesley RW, et al. Genome Res. 2004;14:2235. doi: 10.1101/gr.2648404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wassarman KM, et al. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:37. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01379-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hershberg R, et al. Nuc Acids Res. 2003;31:1813. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rivas E, et al. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1369. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eddy SR. Cell. 2002;109:137. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00727-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sridhar J, Rafi ZA. OMICS. 2007;11:74. doi: 10.1089/omi.2006.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kulikova T, et al. Nuc Acids Res. 2007;35:D16. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. ftp://ftp.sanger.ac.uk/pub4/pathogens/sma

- 16. ftp://ftp.sanger.ac.uk/pub4/pathogens/ye

- 17.Karp PD, et al. Nuc Acids Res. 2002;30:56. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. http://www.sanger.ac.uk/cgi-bin/blast/submitblast/s_marcescens

- 19. http://www.sanger.ac.uk/cgi-bin/blast/submitblast/y_enterocolitica

- 20.Kanehisa M, et al. Nuc Acids Res. 2004;32:D277. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Darling AC, et al. Genome Res. 2004;14:1394. doi: 10.1101/gr.2289704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mao X, et al. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3787. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rice P, et al. Trends Genet. 2000;16:276. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. ftp://ftp.ebi.ac.uk

- 25.Thomson NR, et al. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sridhar J, Rafi ZA. In Silico Biol. 2007;7:0053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.