Abstract

Purpose

We conducted a phase I study of a 30-minute hepatic artery infusion of melphalan via a percutaneously placed catheter and hepatic venous hemofiltration using a double balloon catheter positioned in the retrohepatic inferior vena cava to shunt hepatic venous effluent through an activated charcoal filter and then to the systemic circulation. The purpose of the study was to demonstrate feasibility in an initial cohort and subsequently determine the maximum tolerated dose and dose-limiting toxicity of melphalan.

Patients and Methods

The initial cohort (n = 12) was treated with 2.0 mg/kg of melphalan before dose escalation to 3.5 mg/kg (n = 16). Total hepatic drug delivery, systemic levels, and percent filter efficiency were determined. Patients were assessed for hepatic and systemic toxicity and response.

Results

A total of 74 treatments were administered to 28 patients. Twelve patients with primary and metastatic hepatic tumors received 30 treatments (mean, 2.5 per patient) at an initial melphalan dose of 2.0 mg/kg. At 3.5 mg/kg, a dose-limiting toxicity (neutropenia and/or thrombocytopenia) was observed in two of six patients. Transient grade 3/4 hepatic and systemic toxicity was seen after 19% and 66% of treatments, respectively. An overall radiographic response rate of 30% was observed in treated patients. In the 10 patients with ocular melanoma, a 50% overall response rate was observed, including two complete responses.

Conclusion

Delivery of melphalan via this system is feasible, with limited, manageable toxicity and evidence of substantial antitumor activity; 3 mg/kg is the maximum safe tolerated dose of melphalan administered via this technique.

INTRODUCTION

Unresectable hepatic metastases from solid organ malignancies represent a significant therapeutic challenge in oncology. For patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma, ocular melanoma, and neuroendocrine tumors, liver metastases frequently represent the sole or predominant site of disease progression. Hepatic metastases will develop in up to one fourth of the 140,000 annual new cases of colorectal cancer diagnosed annually in the United States, and the majority of these patients will have unresectable disease.1 For these patients, systemic and hepatic arterial chemotherapy results in median survivals ranging from 12 to 24 months.2,3 For patients with metastatic ocular melanoma who recur, 70% to 90% will develop disease confined to the liver that is multifocal and not amenable to surgical resection.4 Median survival in this group of patients is less than 1 year, and systemic and regional chemotherapy or ablative techniques do not seem to meaningfully impact the natural history of the disease.5,6 Although tumor progression may be indolent, patients with hepatic metastases from neuroendocrine tumors often suffer the sequellae of hormonally active metastases, and strategies for effective palliation of extensive disease are needed.7

The liver has a unique anatomy that provides an opportunity to deliver regional therapy. Established hepatic metastases derive the majority of their blood supply from the hepatic artery, and hepatic arterial infusion of agents with high hepatic clearance during the “first pass” through the hepatic parenchyma allows infusion of high doses of chemotherapy to the diseased organ.8 Such a strategy is limited to agents with a high first pass effect, which limits the types of agents suitable for hepatic artery infusion.

Regional hepatic arterial delivery of high-dose melphalan had been demonstrated to be safe and have efficacy against a variety of tumor histologies confined to the liver, when administered via operative isolated hepatic perfusion (IHP).9,10 IHP is a regional delivery strategy in which complete hepatic vascular inflow and outflow is obtained and the liver perfused via a closed circuit extracorporeal circuit incorporating a roller pump, heat exchanger, and oxygenator.11 Over the last decade, IHP trials performed at our institution and others using melphalan have demonstrated response rates of 60% to 70% in patients with varied histologies. The major disadvantages of this approach are that only a single treatment can be applied and it requires an open surgical procedure with associated morbidity.

Two centers have previously evaluated a regional therapy system for unresectable hepatic malignancies in which fluorouracil or doxorubicin were administered via the hepatic artery and the venous effluent of the liver was collected and filtered using percutaneously placed catheters.12-14 The advantages of this approach are that treatment can be delivered without a major operative procedure, and filtration of the hepatic venous effluent can reduce system exposure of cytotoxic chemotherapy by 80% to 90% compared with hepatic artery infusion alone. In clinical trials conducted during the last 12 years, 33 patients underwent a total of 77 treatments with dose escalation of doxorubicin from 50 to 120 mg/m2. The systemic exposure of doxorubicin was substantially reduced using hepatic venous hemofiltration; however, because antitumor efficacy was not well established, the technique did not gain widespread application. Because melphalan, a small akylating agent, has shown antitumor activity against various tumor histologies when administered via IHP, we conducted a phase I study of percutaneous hepatic perfusion (PHP) with escalating dose melphalan in patients with unresectable hepatic metastases.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design and Patients

Between July 2001 and January 2004, 33 patients with unresectable liver metastases were enrolled on a single phase I trial approved by the institutional review board of the National Cancer Institute. All patients had measurable, unresectable, biopsy-proven hepatic malignancies. Patients underwent standard staging evaluation, including computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis; magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the liver; and, when clinically indicated, bone scans and MRI of the brain. Eligibility criteria included Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of ≤ 2, a serum bilirubin of less than 2.0 mg/dL, a platelet count of more than 100,000, and serum creatinine ≤ 1.5 mg/dL. Patients having a minor, less than 1 to 2 second abnormality on either prothrombin or partial thromboplastin time but who otherwise appeared to have adequate hepatic reserve based on complete evaluation of radiographic and laboratory tests, were considered eligible. We excluded patients who had biopsy-proven cirrhosis or evidence of significant portal hyper-tension by history, endoscopy, or radiologic studies. Patients with limited, extrahepatic disease in the presence of clearly progressive, advanced hepatic metastases were considered eligible for this protocol.

In the feasibility portion of the study, 12 patients were treated at a dose of 2.0 mg/kg before melphalan dose escalation. Subsequent cohorts of three patients were enrolled at 2.5, 3.0, and 3.5 mg/kg. Four additional patients were treated at the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) after a dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) was confirmed in two of six patients.

A planned treatment course included four treatments, each separated by 4 weeks. Before each subsequent treatment, patients were required to have recovered from all toxicity associated with prior treatment. After receiving the second treatment, assessment of tumor response (MRI and/or CT scan) was performed. Patients with evidence of disease progression on interval evaluation were not offered additional treatments. A single patient was re-enrolled on the trial after disease recrudescence following prolonged complete response (CR; 10 months).

Follow-Up Evaluation

All patients were followed up until disease progression with physical examination; laboratory tests; CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis; and MRI of the liver every 3 months for the first year after PHP and every 4 months thereafter.

PHP

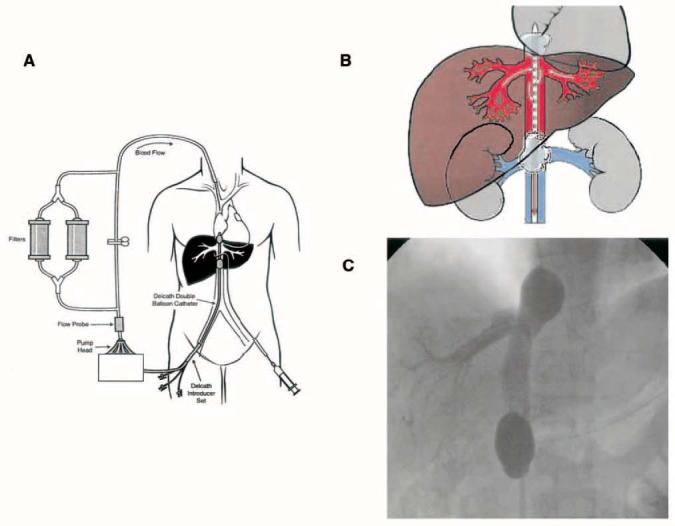

PHP uses a double balloon inferior vena cava (IVC) catheter system (Delcath System; Delcath Inc, Stamford, CT) to isolate hepatic venous outflow and allow high-dose infusion of chemotherapy to the liver. The main component of the system is a 16-F, polyethylene double balloon catheter with one large lumen and three accessory lumina. The two low-pressure occlusion balloons are inflated independently through separate lumina. The cephalic balloon blocks the IVC superior to the hepatic veins, while the caudal balloon obstructs the IVC inferior to the hepatic veins, allowing complete isolation of hepatic venous outflow. The span between the two occlusion balloons consists of a fenestrated segment that feeds into the large, central lumen, which exits the catheter from the proximal end. The additional lumen enters the catheter at a point inferior to the caudal balloon and exits at the distal tip and serves as a channel for a guidewire, and also allows some blood flow from the infrarenal IVC to the right atrium. During the procedure, melphalan is infused through a catheter percutaneously inserted into the hepatic artery. The melphalan perfuses the liver and exits the organ through the hepatic veins. Hepatic venous effluent is collected using the occlusion balloon catheter and melphalan-dosed blood from the central lumen is pumped through an extracorporeal circuit consisting of a centrifugal pump (Biomedicus, Eden Prairie, MN) and hemoperfusion drug filtration cartridges (Hemosorba; Asahi Medical Co, Tokyo, Japan). Melphalan flowing through the circuit is filtered with two activated-carbon filter cartridges arranged in parallel. The filtered blood is returned to systemic circulation via a venous return sheath inserted into the internal jugular vein (Fig 1A).

Fig 1.

(A) Diagram of the Delcath Catheter System (Delcath Inc, Stamford, CT): Melphalan is administered directly into the hepatic artery through a catheter placed percutaneously. Hepatic venous outflow is collected via a double balloon catheter in the retrohepatic inferior vena cava, and run through a pair of activated charcoal filters before return to the systemic circulation. (B) Depiction of the isolated retrohepatic inferior vena cava (IVC): Hepatic venous outflow is isolated by inflating two balloons in the IVC. (C) Fluoroscopic image of the isolated retrohepatic IVC segment obtained by retrograde injection of contrast through the interballoon fenestrations, to confirm the absence of systemic leak. This study is performed while caval flow is obstructed, and thus complete retrograde filling of both hepatic veins is not accomplished.

Treatments are administered with patients under general anesthesia. Bilateral internal jugular veins and the right common femoral vein and artery are accessed using the Seldinger technique and ultrasound guidance. An additional peripheral arterial line was placed for intraoperative management. The extracorporeal circuit is assembled and primed with 0.9% sodium chloride injection. Heparin is administered during the procedure to maintain the activated clotting time at therapeutic levels. Protamine or fresh frozen plasma was given following the procedure to facilitate early catheter and sheath removal. Coordination with anesthesiologists knowledgeable about the effects of IVC occlusion is important. When the balloons are inflated, vasoactive cardiotropic agents are usually required to maintain hemodynamic stability, as venous return is compromised. Additionally, at the time of filter activation, systemic catecholamine levels decrease due to filtration effects. The hepatic arterial catheter is positioned in the proper hepatic artery using standard fluoroscopic and arteriographic techniques. A complete visceral angiogram is performed via both the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries, and the arterial supply to the liver is completely defined. When present, small accessory hepatic arteries and extrahepatic branches are embolized to ensure that the infused chemotherapy is administered only to the liver.

The double balloon catheter is then inserted into the IVC using the Seldinger technique and is positioned under fluoroscopic guidance. The catheter is then attached to the extracorporeal circuit tubing, and the outflow line of the filtration circuit is connected to the venous return sheath. Under fluoroscopy, the cephalad balloon is inflated with dilute contrast medium until the shape of the balloon is no longer round, indicating that it is maximally inflated and free-floating in the right atrium. The balloon is then manipulated with gentle traction until indentation of the diaphragmatic hiatus is visible at the inferior margin. Under fluoroscopy the caudal balloon is inflated with dilute contrast medium until the lateral edges of the balloon deform to the walls of the IVC (Fig 1B). Contrast medium is injected through the fenestrated portion of the catheter to ensure that the balloon catheter is properly placed and the hepatic venous outflow is isolated and without leakage into the right atrium (Fig 1C). The main circuit is established and the filters are brought online.

Melphalan is administered as a 30-minute infusion via the hepatic artery. Following infusion, the extracorporeal filtration circuit is continued for an additional 30 minutes. At completion, the balloons are deflated, and the catheters are removed. The patient is kept on bed rest and is monitored in the intensive care unit for 12 hours.

Toxicity

Systemic and regional toxicity were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria, version 3.0. Acute systemic toxicity that corrected within 24 hours of treatment was not considered dose limiting. Fever, nausea, and weight gain were not used to define the DLT. Per protocol, DLT was defined as (1) grade 4 neutropenia of greater than 72 hours' duration or associated with neutropenic fever, (2) grade 3 thrombocytopenia of greater than 72 hours' duration or associated with significant clinical bleeding, (3) grade 4 hemoglobin of greater than 7 days' duration, or (4) grade 3 or 4 major nonhematologic organ toxicity not correctable within 24 hours of the procedure.

Response

All patients had measurable disease before enrolling on the study, and 27 of 28 treated patients were assessable for response. A single patient withdrew from the study after one treatment and is included in the toxicity assessment only. Because PHP is a regional treatment, response and duration of response were scored only for lesions in the liver, and recurrences were noted as intrahepatic and/or extrahepatic. Standard RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors) criteria were used to assess response. Target lesions were classified as follows: CR, disappearance of all target lesions; partial response (PR), at least a 30% decrease in the sum of the longest diameter (LD) of target lesions taking as reference the baseline sum LD; progression, at least a 20% increase in the sum of LD of target lesions taking as reference the smallest sum LD recorded since the treatment started or the appearance of one or more new lesions; or stable disease, neither sufficient shrinkage to qualify for PR nor sufficient increase to qualify for progression taking as references the smallest sum LD. Assessment of nontarget lesions was also recorded.

The duration of overall response was measured from the time of initial treatment until the first date that recurrent or progressive disease was objectively documented (taking as reference for progressive disease the smallest measurements recorded since the initiation of treatment). The duration of overall CR was measured from the time treatment was initiated until the first date that recurrent disease was objectively documented. Stable disease was measured from the start of the treatment until the criteria for progression were met, taking as reference the smallest measurements recorded since the treatment started. Since therapy is limited only to the liver and the entry criteria limit treatment to patients with primarily hepatic disease, responses were only assessed on the measurable hepatic lesions. New lesions occurring outside the liver were scored separately from new lesions occurring within the liver.

Pharmacologic Studies

Blood samples were obtained simultaneously from the periphery (arterial line) and the extracorporeal circuit (both pre- and postfilter) at baseline; midinfusion; immediately on completion of infusion; and at 5, 10, 15, and 30 minutes after infusion. Melphalan levels were assessed from the melphalan arterial infusion catheter in order to ensure drug stability during the 30-minute infusion. The efficiency of melphalan extraction by the activated charcoal filters was determined utilizing a previously developed and validated method. Patients had PK levels drawn during their first two PHPs, but not during the last two PHPs, as no intrapatient dose escalation was performed. During the dose escalation phase of the study, pharmacokinetics were analyzed before the next patient entry on study.

Statistics

All data are presented as mean ± SE or standard deviation, as indicated.

RESULTS

Demographic information for all 28 patients who received at least one treatment is presented in Table 1. An equal percentage of men and women were treated, with a mean age of 49 years (range, 17 to 74 years). Five additional patients (15.2%) were not treated due to anatomic abnormalities not seen on preoperative imaging, which precluded safe treatment. In three of these patients, balloon occlusion of the suprahepatic IVC was not possible secondary to the relationship between the hepatic veins and the right atrium (n = 2) or the length of the retrohepatic IVC (n = 1). Another patient who was previously treated with hepatic artery infusional therapy had a diffusely sclerotic hepatic artery precluding catheterization. In a fifth patient, catheterization of the hepatic artery resulted in a hepatic artery dissection. Although the patient suffered no additional sequelae, no treatment was administered due to risk of repeat arterial injury. In the 28 treated patients, the site of origin of metastases was ocular melanoma (n = 10), neuroendocrine neoplasms (n = 4), colorectal cancer (n = 2), cutaneous melanoma (n = 3), adrenal adenocarcinoma (n = 1), pancreatic adenocarcinoma (n = 1), retroperitoneal sarcoma (n = 1), breast adenocarcinoma (n = 1), and renal cell carcinoma (n = 2). Three additional patients had primary, unresectable hepatobiliary tumors. One third of patients had limited extrahepatic disease, manifest by small pulmonary nodules or isolated nodal or soft tissue metastases in the presence of progressive, life-limiting hepatic metastases. The majority of patients had received previous treatment for their hepatic metastases, including systemic chemotherapy (n = 13), regional chemotherapy (n = 7), resection (n = 4), or radiofrequency ablation (n = 2). All patients not undergoing any previous therapy had metastatic ocular melanoma. All patients had a good pretreatment performance status.

Table 1.

Demographics of Treated Patients

| Patients |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | No. | % | |

| Patients (treated) | 28 | ||

| Treatments | 74 | ||

| Treatments per patient | |||

| Mean | 2.6 | ||

| 1 | 5 | 18 | |

| 2 | 10 | 36 | |

| 3 | 3 | 13 | |

| 4 | 10 | 36 | |

| Male-female ratio | 14:14 | ||

| Age, years | |||

| Mean | 49 | ||

| Range | 17-74 | ||

| Extrahepatic disease | 8 | 29 | |

| Previous treatment | 21 | 75 | |

| Hepatic resection | 4 | 14 | |

| RFA, cryoablation | 2 | 7 | |

| Systemic chemotherapy | 13 | 46 | |

| HAI chemotherapy/IHP | 7 | 25 | |

| Embolization | 2 | 7 | |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Ocular melanoma | 10 | 36 | |

| Cutaneous melanoma | 3 | 11 | |

| Colorectal | 2 | 7 | |

| Periampullary adenoma | 1 | 4 | |

| Hepatobiliary | 3 | 11 | |

| Neuroendocrine neoplasm | 4 | 14 | |

| Breast | 1 | 4 | |

| Sarcoma | 1 | 4 | |

| Adrenocortical | 1 | 4 | |

| Renal cell | 2 | 7 | |

| ECOG* | |||

| 0 | 65 | 88 | |

| 1 | 8 | 11 | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | |

Abbreviations: RFA, radiofrequency ablation; HAI, hepatic artery infusional; IHP, isolated hepatic perfusion; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

At time of treatment.

The perfusion and treatment parameters of the 74 treatments are presented in Table 2. All patients completed the planned 30-minute melphalan infusion. In all but three treatments, an additional 30 minutes of hemofiltration was performed in order to eliminate any residual chemotherapy. Three patients had an abbreviated postinfusion filtration phase due to decreased venovenous circuit flow rates of undetermined etiology. Overall, the 71-minute median venovenous bypass time represents the time to inflate and seat the proximal and distal balloons in addition to the chemotherapy infusion and hepatic washout. Venovenous bypass flow rates were consistent throughout the trial with the exception of six treatments early in the series when low flow rates were noted secondary to malpositioning of the venous inflow catheter. Mean procedure time decreased by an average of 40 minutes for an individual patient after the initial treatment, as diagnostic arteriography and gastroduodenal arterial embolization was not repeated on subsequent treatments. Eighteen percent of patients had dual-artery chemotherapy infusion secondary to accessory or replaced hepatic arterial anatomy, requiring dual infusion catheters and prolonged procedure times. Blood loss was minimal and was largely a consequence of the inability to return all blood from the venovenous bypass circuit at the completion of the procedure. Postoperative coagulopathy was treated with fresh frozen plasma and heparin reversal with protamine to facilitate prompt catheter removal. Vasopressor support was utilized during the majority of treatments at the time of balloon inflation and the initiation of hemofiltration, corresponding to periods of decreased venous return and filtration of circulating catecholamines, respectively. Initially, these effects were treated with intravenous fluids, but early administration of low-dose phenylephrine decreased the need for significant intraoperative fluid administration. At the completion of the procedure, patients were maintained in the ICU until arterial and venous catheters were removed. Patients were ambulatory and advanced to a regular diet within 24 hours of treatment. The small number of treatment-related complications (Table 2) secondary to central line placement (hematoma, pneumothorax, and inadvertent arterial puncture) and therapeutic anticoagulation (hematuria and intratumor hemorrhage) are consistent with the nature of therapeutic interventions performed.

Table 2.

Perfusion and Treatment Parameters

| Patients, No. | 28 |

| Treatments, No. per patient | 74 |

| Procedure length, minutes | |

| Median | 300 |

| Range | 205-515 |

| Bypass flow rate, mL/min | |

| Median | 875 |

| Range | 200-1,200 |

| Venovenous bypass, minutes | |

| Median | 71 |

| Range | 32-109 |

| Medications required | |

| Protamine, No. of patients | 66 |

| FFP, U | |

| Median | 2 |

| Range | 2-6 |

| Vasopressor support, No. of patients | 70 |

| Infusion route (28 patients), No. of patients | |

| Single artery | 23 |

| Double artery | 5 |

| Estimated blood loss, mL | |

| Median | 200 |

| Range | 50-900 |

| Transfused PRBCs, U | |

| Median | 0.9 |

| Range | 0-4 |

| Length of stay, days | |

| Median | 2.5 |

| Range | 2-6 |

| Procedure complications, No. of treatments* | |

| Pneumothorax | 1 |

| Arterial puncture | 1 |

| Cervical hematoma | 1 |

| Hepatic artery dissection | 1 |

| Intratumor hemorrhage | 1 |

| Protamine reaction | 1 |

| Hematuria | 1 |

| Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia | 1 |

Abbreviations: FFP, fresh frozen plasma; PRBCs, packed RBCs.

Total procedural complications while on study.

A total of 12 patients were treated at the initial dose level of 2.0 mg/kg (Table 3). At each subsequent dose level, three patients were treated as part of the dose escalation, with an additional four patients treated after the MTD had been established. At the initial dose level, the total dose given ranged from 90 to 150 mg. Three patients received 2.5 mg/kg (range, 135 to 147 mg), and seven were treated at 3.0 mg/kg (range, 153 to 212 mg). In the 3.5-mg/kg group, dose-limiting neutropenia or thrombocytopenia were observed in two of six patients. In addition, we noted a delay in recovery from grade 3 and 4 toxicities between treatments, leading to treatment delays. In the two patients with DLT, additional treatments were carried out using 3.0 mg/kg of melphalan. Subsequently, four additional patients were treated at 3.0 mg/kg to confirm MTD.

Table 3.

Dosing Characteristics

| Dose (mg/kg) |

Patients (No.) |

Melphalan Dose (mg) |

Treatments/Patient (No. of treatments) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Range | Mean | Range | ||

| 2.0 | 12 | 128 | 90-150 | 2 | 1-4 |

| 2.5 | 3 | 142 | 135-147 | 4 | 2-4 |

| 3.0 | 7 | 182 | 153-212 | 2 | 1-4 |

| 3.5 | 6* | 224 | 175-257 | 3 | 2-4 |

Dose reduction to 3.0 mg/kg in three patients.

Table 4 lists all toxicities at each melphalan dose. The initial cohort of 12 patients received a total of 30 treatments without DLT. Transient grade 3/4 systemic toxicity was noted after 20 of 30 treatments (67%) and was universally hematologic in nature. Grade 3/4 neutropenia required treatment with filgrastim after 12 of 30 treatments. Three patients underwent 10 treatments at 2.5 mg/kg, with transient grade 3/4 neutropenia encountered after eight of the 10 treatments. Seven patients underwent 19 treatments at 3.0 mg/kg, including two patients who were dose reduced from 3.5 mg/kg to 3.0 mg/kg as a result of DLT. In all, 19 treatments were administered at the MTD. Grade 4 neutropenia requiring outpatient administration of filgrastim was experienced after 11 treatments. Four patients had self-limited, grade 3/4 anemia. The grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia observed after seven treatments required transfusion after one treatment.

Table 4.

Toxicity per Treatment

| Neutropenia |

Thrombocytopenia |

Anemia |

Hepatic |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose (mg/kg) | Patients/Treatments | Grade I/II | Grade III/IV | Grade I/II | Grade III/IV | Grade I/II | Grade III/IV | Grade I/II | Grade III/IV |

| 2.0 | 12/30 | 10 | 17 | 14 | 11 | 24 | 3 | 22 | 5 |

| 2.5 | 3/10 | 2 | 8 | 7 | — | 7 | 2 | 8 | 2 |

| 3.0 | 7/19* | 2 | 14 | 9 | 7 | 12 | 4 | 16 | 1 |

| 3.5 | 6/15 | 3 | 10 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 6 |

| Total | 28/74 | 17 | 49 | 36 | 26 | 48 | 13 | 54 | 14 |

Includes two treatments after dose reduction from previous cycle dose of 3.5 mg/kg.

Six patients underwent 15 treatments with 3.5 mg/kg melphalan. Grade 3/4 neutropenia was observed after 10 treatments (66%), requiring treatment with filgrastim in three cases. At this highest dose level, we observed increased rates of additional bone marrow toxicity as manifest by grade 3/4 anemia (n = 4; 40%) and thrombocytopenia (n = 8; 80%), often requiring RBC (n = 3) or platelet transfusion (n = 4) was observed. In the two patients experiencing DLT, one was secondary to prolonged grade 3 thrombocytopenia, and the other, from both prolonged grade 4 neutropenia and grade 3 thrombocytopenia. In patients who experienced DLT, dose reduction to 3.0 mg/kg was performed for all subsequent treatments. In addition to the increased rate of grade 3/4 toxicity, the time to full recovery from non-DLTs was increased at this dose, resulting in delays of subsequent treatments.

Significant, nonhematologic toxicity was rare in patients treated on this trial. Grade 3/4 toxicity was noted after only 14 treatments (18.9%) and was universally transient. No renal, cardiac, or pulmonary toxicity was observed. One patient experienced an anaphylactic reaction to protamine sulfate administration. A single additional patient developed a hepatic artery dissection at the time of arteriography and was removed from the trial. Two patients were taken off the trial as a result of treatment-related complications—one who developed heparin-induced thrombocytopenia after a single treatment, and the previously mentioned hepatic artery dissection.

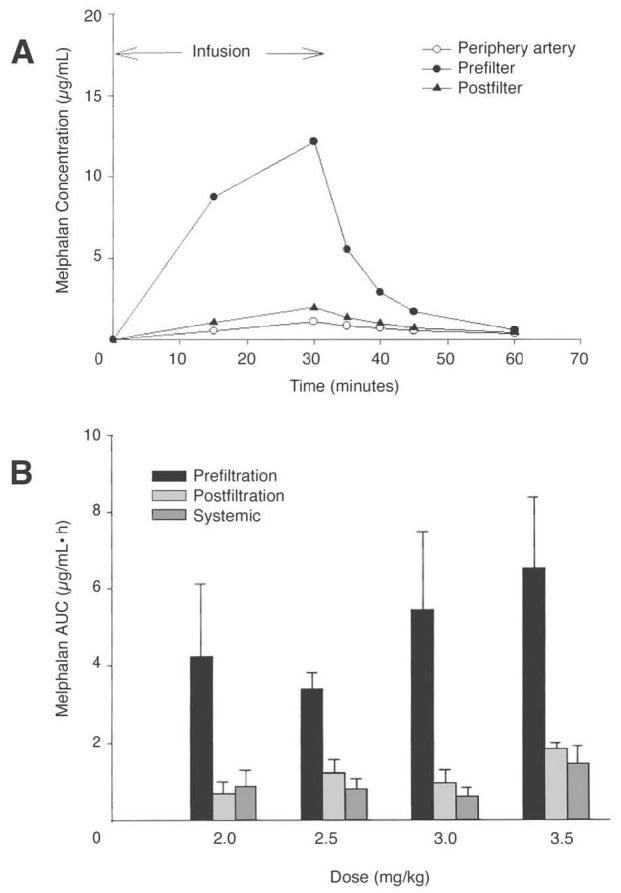

A comprehensive pharmacokinetic profile of patients undergoing PHP treatments was performed. All patients treated during the initial and dose-escalation phases had serial assessment of melphalan concentrations in the infusion catheter, the pre- and postfilter circuit, and the systemic circulation (Fig 2). Table 5 presents the pharmacokinetic data. There was no degradation of melphalan during the 30-minute infusion (data not shown). Filter extraction percentages ranged from 58.2% to 94.7%, with a mean of 77%. There was no change in filter efficiency during melphalan dose escalation. Increasing melphalan dose was associated with increased hepatic drug delivery as measured by both the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) and maximum concentration (Cmax). Total hepatic delivery of melphalan, as measured by prefilter AUC, ranged from 4.24 ± 1.87 μg/mL/h at the initial dose of 2.0 mg/kg to 6.50 ± 1.84 μg/mL/h at DLT (3.5 mg/kg). Peak drug delivery (prefilter Cmax) ranged from 8.52 ± 3.46 μg/mL/h at 2.0-mg/kg dosing to 11.90 ± 3.68 μg/mL/h at MTD. There was rapid clearance of melphalan from the liver during the first 10 minutes after melphalan infusion was complete (Fig 2A). Figure 2B graphically illustrates the magnitude of difference between hepatic and systemic drug exposure as measured by both AUC and Cmax. At the MTD, mean filter efficiency was measured at 78.5% with melphalan AUC of 5.42 ± 2.04 μg/mL/h and Cmax of 11.82 ± 6.14 μg/mL/h.

Fig 2.

(A) Intrahepatic melphalan delivery. The pharmacokinetic profile of a single treatment demonstrates the rapid establishment of Cmax in the hepatic circulation, followed by a rapid washout phase. (B) Graphic representation of filter efficiency across multiple melphalan dosing cohorts. AUC, area under the concentration-time curve.

Table 5.

Melphalan Pharmacokinetic Parameters and Extraction Efficiency at Different Melphalan Doses

| AUC (μg/mL/hr) |

Extraction (%); (pre-post/pre) |

Cmax (μg/mL) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose (mg/kg) N | Prefilter | Postfilter | Right Arterial | Prefilter | Postfilter | Right Arterial | |

| 2 mg/kg (n = 11) | |||||||

| Mean | 4.24 | 0.68 | 0.89 | 82.0 | 8.52 | 1.23 | 1.50 |

| SD | 1.87 | 0.33 | 0.41 | 8.8 | 3.46 | 0.69 | 0.73 |

| Median | 4.00 | 0.49 | 0.73 | 79.8 | 8.05 | 0.88 | 1.16 |

| 2.5 mg/kg (n = 11) | |||||||

| Mean | 3.41 | 1.23 | 0.82 | 64.0 | 7.197 | 2.697 | 1.677 |

| SD | 0.41 | 0.35 | 0.25 | 7.9 | 2.36 | 1.46 | 0.89 |

| Median | 3.38 | 1.18 | 0.82 | 60.8 | 6.57 | 1.96 | 1.31 |

| 3 mg/kg (n = 3) | |||||||

| Mean | 5.42 | 0.97 | 0.63 | 78.5 | 11.82 | 1.89 | 1.11 |

| SD | 2.04 | 0.35 | 0.22 | 15.2 | 6.14 | 0.48 | 0.29 |

| Median | 5.29 | 0.98 | 0.55 | 81.5 | 12.17 | 2.01 | 1.15 |

| 3.5 mg/kg (n = 3) | |||||||

| Mean | 6.50 | 1.85 | 1.46 | 70.0 | 11.90 | 3.44 | 2.23 |

| SD | 1.84 | 0.16 | 0.47 | 8.5 | 3.68 | 0.74 | 1.31 |

| Median | 5.92 | 1.78 | 1.29 | 65.7 | 12.40 | 3.43 | 1.68 |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the concentration = time curve; Cmax, maximum concentration; SD, standard deviation.

Although response and survival analyses are not primary end points of this phase I trial, 27 of 28 patients were assessable for response (Table 6). Antitumor activity included minor responses (n = 10), PRs (n = 6), and two CRs. In the 10 patients with metastatic ocular melanoma, objective tumor response was documented in 50% (PR, n = 3; CR, n = 2). The duration of PRs includes two patients with ongoing responses at 9 and 11 months, respectively. Duration of the two CRs was 10 and 12 months, respectively (Fig 3). Minor responses were noted in an additional three patients (30%). Four patients with progressing hepatic metastases from pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors were treated, with ongoing PRs in two patients at 5 and 7 months, respectively, and an additional ongoing minor response (10 months). In both patients with ongoing PRs, response has correlated with symptom relief and decreased hormone levels.

Table 6.

Treatment Response in 27 Assessable Patients

| MR |

PR |

CR |

Overall (PR + CR) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histology | No. of Patients |

No. of Patients |

Durations (months) |

No. of Patients |

Durations (months) |

No. of Patients |

Durations (months) |

No. | % |

| Ocular melanoma | 10 | 3 | 7, 8, 3+ | 3 | 7, 9+, 11+ | 2 | 10, 12 | 5 | 50 |

| Cutaneous melanoma | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0 | — |

| Neuroendocrine | 3 | 1 | 10+ | 2 | 3+, 7+ | — | — | 2 | — |

| Colorectal | 1 | 1 | 9 | — | — | — | — | 0 | — |

| Adrenal | 1 | — | — | 1 | 10+ | — | — | 1 | — |

| Other | 7 | 5 | 6, 4, 3+, 3+, 2 | — | — | — | — | 0 | — |

| Total | 27 | 10 | — | 6 | — | 2 | — | 8 | 29.6 |

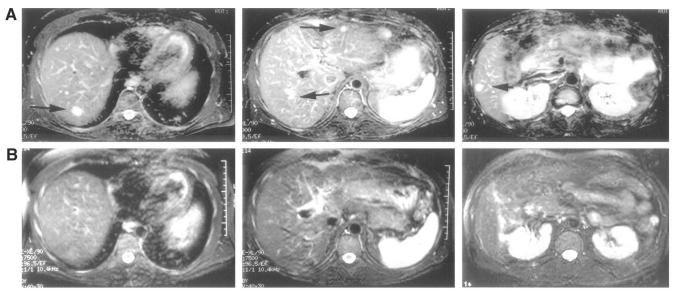

Fig 3.

A 38-year-old man with metastatic ocular melanoma treated with four Delcath hepatic perfusions with melphalan. A complete response was observed for 10 months, at which time new hepatic metastases were noted. The patient underwent a second series of four treatments with a similar response and no cumulative toxicity. PHP, percutaneous hepatic perfusion.

DISCUSSION

These results demonstrate that a novel regional treatment of hepatic metastases, PHP, can be safely performed, with predictable and manageable toxicity. An MTD of melphalan delivered through the hepatic artery has been defined as 3.0 mg/kg. Although there is no statistically significant evidence that cumulative toxicity occurs after multiple treatments, clinical observations seemed to indicate a slightly more prolonged resolution of post-treatment systemic toxicity after successive treatments. The MTD reported here is greater than that reported with either systemic or intraoperative regional administration.15,16 The doses of drug administered in this trial are similar to those utilized in association with systemic administration in bone marrow transplantation.17 Advocates of regional therapy point to the ability to deliver higher doses of therapeutic agents to a focused anatomic area while limiting overall toxicity. This approach utilizes an agent (melphalan) shown to be effective in other regional strategies. Systemic administration of melphalan is limited secondary to bone marrow toxicity. Previous investigators have examined the utility of this system for the delivery of regional fluorouracil and doxorubicin. Although filter extraction rates of 85% to 95% were reported, studies did not provide sufficient efficacy data to generategeneraqte interest in continued clinical investigation.

For patients with unresectable hepatic metastases, treatment options are limited. Ablative therapies are effective for patients with limited numbers of tumors smaller than 7 cm.18 Other approaches such as bland or chemoembolization19 and selective internal radiation20 have not been demonstrated to impact overall survival. In patients with certain malignancies, including ocular melanoma,21 gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas,22 and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors,23 the liver frequently represents a site of preferential metastasis. For such patients, these metastases often dictate quality of life and survival, and are frequently refractory to intravenous systemic chemotherapy. Regional therapy offers the advantage of focused drug delivery to the entire diseased organ. We have demonstrated the ability to limit systemic toxicity while delivering high levels of intrahepatic melphalan, as confirmed by measuring hepatic and systemic melphalan Cmax and AUC. The design of the circuit with this system prohibits the use of hyperthermia. Hyperthermia has been shown to augment melphalan cytotoxicity or antitumor activity in experimental models.24,25 Although it is routinely used in isolation perfusion of the limb and liver, the current data suggest that significant antitumor activity can be achieved with regional administration of melphalan without hyperthermia.

Simple intra-arterial therapy may offer therapeutic advantages over systemic drug delivery by reducing the overall volume of distribution of drug during the initial hepatic exposure to melphalan. We examined the concentration of drug in the hepatic venous effluent in order to establish filter efficiency, and demonstrated that the majority of drug was removed by the filter. Overall, a 10-fold increase in the hepatic versus systemic Cmax of melphalan was observed at the MTD. The ability to filter drug present in the hepatic venous effluent is a vital component of this approach, as all DLT and other significant toxicities were related to extrahepatic melphalan exposure. The systemic exposure of melphalan most likely results from a combination of unfiltered drug reflected in the postfilter samples as well as some drug that is not collected in the hepatic venous catheter. The evidence for the latter is that systemic melphalan levels are almost the same as postfilter samples, which would be unlikely if the only source of systemic melphalan were derived from filtration inefficiency. Although the exact location at which melphalan escapes into the systemic circulation is not known, it is not from leakage around the double-balloon catheter in the vena cava, as pre- and post-treatment fluoroscopy confirmed complete vena caval isolation.

The short length of hospitalization and the ability to treat toxicity in the outpatient setting in all except one case is the best indication of how well patients tolerated this intervention. After 70 of 74 treatments, patients were ambulatory and on a regular diet within 24 hours after treatment. The median length of stay greater than 24 hours reported in this series is an artifact of the referral patterns of our institution, where the overwhelming majority of patients travel from out of state to receive care. To completely assess acute toxicity in this study, we kept patients hospitalized for a minimum of 48 hours post-treatment. There was no deterioration in performance status noted in patients undergoing multiple treatments. Self-limited, transient grade 3/4 hepatic toxicity was observed after 14 (18.9%) of 74 treatments. In all patients, subsequent arteriogram revealed intact hepatic arterial anatomy before initiation of additional treatments. The only two patients removed from the trial for reasons other than disease progression were a patient with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and one with a hepatic artery dissection.

Although this phase I trial was designed to assess toxicity during dose escalation, there is evidence indicating meaningful antitumor effects from this treatment strategy, even at doses below MTD. The majority of patients accrued to this trial had tumor histologies that have historically demonstrated some sensitivity to melphalan, including melanoma (ocular and cutaneous), pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, and gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas, with the largest number of patients constituting the first two tumor types. The overall response rate observed in this trial was 29.6%, including two patients with CRs. In addition, antitumor effects were demonstrated in another 10 patients (37%) who experienced less than 30% regression of previously enlarging tumors. Patients with ocular melanoma and neuroendocrine tumors represented a significant percentage those enrolled on this trial. The impact of previous therapy is difficult to assess due to the variety of histologies represented in this group. Patients who had not demonstrated a response to regionally delivered melphalan were not considered for treatment. Five patients who had previously demonstrated tumor sensitivity to regional melpahlan were successfully treated on this protocol, resulting in two PRs and two minor responses. This represents a referral bias, as well as the paucity of available effective therapies. Initial results indicate that response rates for both of these diseases are comparable to other, potentially more toxic therapies, and will be studied separately in the phase II setting.

In summary, PHP with melphalan can be performed safely at an MTD of 3.0 mg/kg. Unlike other hepatic directed therapies, however, regional toxicity was minimal. Although not designed to evaluate response, the data available from this phase I trial suggest antitumor activity against a variety of tumor histologies. These results parallel results seen with operative delivery of melphalan and will serve as the basis for patient selection for phase II studies. The effective number of treatments needs to be defined in further studies, but more frequent dosing does not appear possible due to the delayed onset of toxicity observed in this trial. A large percentage of patients continue to experience manageable grade 3 and 4 hematologic toxicity. Early data regarding antitumor efficacy is encouraging and mirrors our experience with surgical liver perfusion with melphalan. The future of regional cancer therapies is dependent on the ability to delivery biologically significant increased levels of therapeutic agents in a cost-effective manner. The short hospitalization, the low complication rate, and the potential to introduce other, more disease-specific agents into this system justify continued investigation of this percutaneous strategy against unresectable liver tumors. Phase II trials for patients with melanoma, colorectal, neuroendocrine, and primary hepatic tumors are being initiated.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Chicago, IL, May 31-June 3, 2003.

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Murray T, Samuels A, et al. Cancer statistics, 2003. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53:5–26. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.53.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rothenberg MC, Oza AM, Bigelow RH, et al. Superiority of oxaliplatin and fluourouracilleucovorin compared with either therapy alone in patients with progressive colorectal cancer after irinotecan and fluorouracil-leucovorin: Interim results of a phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2059–2069. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kemeny N, Gonen M, Sullivan D, et al. Phase I study of hepatic arterial infusion of floxuridine and dexamethasone with systemic irinotecan for unresectable hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2687–2695. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.10.2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egan KM, Seddon JM, Glynn RJ, et al. Epidemiologic aspects of uveal melanoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 1988;32:239–251. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(88)90173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gragoudas ES, Egan KM, Seddon JM, et al. Survival of patients with metastases from uveal melanoma. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:383–390. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32285-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kath R, Hayungs J, Bornfeld N, et al. Prognosis and treatment of disseminated uveal melanoma. Cancer. 1993;72:2219–2223. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19931001)72:7<2219::aid-cncr2820720725>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sutliff VE, Doppman JL, Gibril F, et al. Growth of newly diagnosed, untreated metastatic gastrinomas and predictors of growth patterns. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2420–2431. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sigurdson ER, Ridge JA, Daly JM. Fluorodeoxyuridine uptake by human colorectal hepatic metastases after hepatic artery infusion. Surgery. 1986;100:285–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexander HR, Libutti SK, Bartlett DL, et al. A phase I-II study of isolated hepatic perfusion using melphalan with or without tumor necrosis factor for patients with ocular melanoma metastatic to liver. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:3062–3070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander HR, Bartlett DL, Libutti SK. Current status of isolated hepatic perfusion with or without tumor necrosis factor for the treatment of unresectable cancers confined to liver. Oncologist. 2000;5:416–424. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-5-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Libutti SK, Bartlett DL, Fraker DL, et al. Technique and results of hyperthermic isolated hepatic perfusion with tumor necrosis factor and melphalan for the treatment of unresectable hepatic malignancies. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:519–530. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(00)00733-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curley SA, Stone DL, Fuhrman GM, et al. Increased doxorubicin levels in hepatic tumors with reduced systemic drug exposure achieved with complete hepatic venous isolation and extracorporeal chemofiltration. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1993;33:251–257. doi: 10.1007/BF00686224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curley SA, Byrd DR, Newman RA, et al. Reduction of systemic drug exposure after hepatic arterial infusion of doxorubicin with complete hepatic venous isolation and extracorporeal chemofiltration. Surgery. 1993;114:579–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ravikumar TS, Pizzorno G, Bodden W, et al. Percutaneous hepatic vein isolation and high-dose hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy for unresectable liver tumors. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:2723–2736. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.12.2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samuels BL, Bitran JD. High-dose intravenous melphalan: A review. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1786–1799. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.7.1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alexander HR, Bartlett DL, Libutti SK, et al. Isolated hepatic perfusion with tumor necrosis factor and melphalan for unresectable cancers confined to the liver. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1479–1489. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lazarus HM, Gray R, Ciobanu N, et al. Phase I trial of high-dose melphalan, high-dose etoposide and autologus bone marrow reinfusion in solid tumors: An Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1994;14:443–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curley SA, Izzo F, Delrio P, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of unresectable primary and metastatic hepatic malignancies: Results in 123 patients. Ann Surg. 1999;230:1–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199907000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groupe d'Etude et de Traitement du Carcinome Hepatocellulaire A comparison of lipiodol chemoembolization and conservative treatment for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1256–1261. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505113321903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrews JD, Walker SC, Ackermann RJ, et al. Hepatic radioembolization with Yttrium-90 containing glass microspheres: Preliminary results and clinical follow-up. J Nucl Med. 1994;35:1637–1644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rajpal S, Moore R, Karakousis CP. Survival in metastatic ocular melanoma. Cancer. 1983;52:334–336. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19830715)52:2<334::aid-cncr2820520225>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fong Y, Fortner J, Sun RL, et al. Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 1999;230:309–321. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199909000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yao KA, Talamonti MS, Nemcek A, et al. Indications and results of liver resection and hepatic chemoembolization for metastatic gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors. Surgery. 2001;130:677–682. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.117377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller RC, Richards M, Baird C, et al. Interaction of hyperthermia and chemotherapy agents: Cell lethality and oncogenic potential. Int J Hyperthermia. 1994;10:89–99. doi: 10.3109/02656739409009335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joiner MC, Steel GG, Stephens TC. Response of two mouse tumours to hyperthermia with CCNU or melphalan. Br J Cancer. 1982;45:17–26. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1982.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]