Abstract

Mxi1 is a Mad family member that plays a role in cell proliferation and differentiation. To test the role of Mxi1 on tumorigenesis of glioma cells we transfected a CMV-driven MXI1 cDNA in U87 human glioblastoma cells. Two clones were isolated expressing MXI1 levels 18- and 3.5-fold higher than wild-type U87 cells (clone U87.Mxi1.14 and U87.Mxi1.22, respectively). In vivo, U87.Mxi1.14 cells were not tumorigenic in nude mice and delayed development of tumours was observed with U87.Mxi1.22 cells. In vitro, the proliferation rate was partially and strongly inhibited in U87.Mxi1.22 and U87.Mxi1.14 cells respectively. The cell cycle analysis revealed a relevant accumulation of U87.Mxi1.14 cells in the G2/M phase. Interestingly, the expression of cyclin B1 was inhibited to about 60% in U87.Mxi1.14 cells. This inhibition occurs at the transcriptional level and depends, at least in part, on the E-box present on the cyclin B1 promoter. Consistent with this, the endogenous Mxi1 binds this E-box in vitro. Thus, our findings indicate that Mxi1 can act as a tumour suppressor in human glioblastomas through a molecular mechanism involving the transcriptional down-regulation of cyclin B1 gene expression.

British Journal of Cancer (2002) 86, 477–484. DOI: 10.1038/sj/bjc/6600065 www.bjcancer.com

© 2002 The Cancer Research Campaign

Keywords: Mxi1, cyclin B1 promoter, tumour suppressor

The oncogenic transformation by Myc proteins requires a basic helix-loop-helix leucine zipper (bHLH-zip)-mediated interaction with Max, the Myc obligate DNA-binding partner (Dang et al, 1989; Blackwell et al, 1990; Kretzner et al, 1992). Proteins of the Myc network are essential regulators of cell growth and differentiation (Henriksson and Luscher, 1996). The Mad family proteins (Ayer et al, 1993; Zervos et al, 1993; Hurlin et al, 1995), among which Mxi1, can antagonize Myc by interacting with Max. This complex recruits Sin3A or Sin3B transcriptional repressors, the co-repressor N-CoR, and the histone deacetylase HDAC1 (Schreiber-Agus et al, 1995; Rao et al, 1996; Alland et al, 1997; Hassig et al, 1997; Laherty et al, 1997). Direct repression of the c-Myc promoter by Mxi1 can also take place (Lee and Ziff, 1999).

Because of their molecular function, proteins of the Mad family are potentially involved in tumour suppression. In particular, a deficient function of these proteins could contribute to tumorigenesis by making available large amounts of Max for c-Myc activation. Chen et al (1995) have provided evidences for an inhibitory role of Mad1 on malignant gliomas. The recent knock out of MXI1 in mice has confirmed its role as a tumour suppressor (Schreiber-Agus et al, 1998; Foley and Eisenman, 1999).

MXI1 gene has been mapped to the chromosome region 10q25, frequently deleted in glioblastomas (Rasheed et al, 1992; Fults and Pedone, 1993; Edelhoff et al, 1994; Albarosa et al, 1996). The over-expression of Mxi1 in glioblastoma cells suppresses cell growth, inducing an accumulation of the cells in the G2/M phases of the cell cycle (Wechsler et al, 1997).

The target genes by which Mxi1 exerts its effect on the cell cycle progression are still not identified. Here we demonstrate that during the Mxi1-induced G2/M block in glioblastoma cells, the expression of the master regulatory gene of the G2 progression, cyclin B1 is down-regulated at transcriptional level, indicating that cyclin B1 is a target of Mxi1 activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Transfection of U87 cells by a Mxi1 eukaryotic expression plasmid

Total RNA was prepared after direct lysis of lymphocytes with Tripure reagent (Roche). Two rounds of reverse transcription were performed starting from 5 μg of total RNA, using oligo (dT) primer, other reagents and procedures contained in the cDNA Cycle Kit from Invitrogen. Four μl of the resulting cDNA, 50 pmoles of each primer, 0.2 mM dNTPs and 2.5 units of either Taq or HF-Taq DNA polymerase, with the respective buffers from Roche, were used for two rounds of PCR. The first round was performed using primers Mxi1-A1 (TAAGGGAGTGCGGAGAGG) and Mxi1-R (TTAAATACAGGTCCTCTGACCC). The initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min was followed by 30 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 2 min and 72°C for 3 min. One μl of the PCR mixture was subjected to a second round of amplification under the same conditions using primers Mxi1-A1 and Mxi1-R2b (CATGCTGGGTTCTATGAAGAG). The resulting 740 bp fragment was cloned into pCR3 eukaryotic expression plasmid (Invitrogen) in both orientations. The sequence of amplified MXI1 cDNA corresponds to wild-type MXI1 except for two nucleotide changes at codon 178 (GAA to GGA) and 195 (AGT to GGT) predicting, respectively, a glycine for glutamate and a glycine for serine substitution. These changes, present in the plasmid transfected in the cells used for 3H incorporation assays, were likely due to PCR amplification, since they were never found by SSCP analysis of glioma and lymphocyte DNA of 36 unrelated individuals (G Finocchiaro unpublished data). Moreover they are not placed in the four regions that are critical for Mxi1 transcriptional activity (SR1 domain, basic region, HLH domain and leucine zipper domain, aa 1–147, ibidem). As assessed by sequence information, the cells used in the cell counting and colonies formation assays, have been transfected with a plasmid carrying a wild-type sequence of Mxi1 derived from a different PCR.

The human U87 glioma cell line (ATCC HTB 14), was grown in Eagle's medium (EMEM) supplemented with 10% foetal calf serum, non-essential amino acids, sodium pyruvate, L-glutamine, streptomycin and penicillin. U87 cells (80% confluent) were lipofected by DOTAP (Roche) using 5 μg of pCR3/Mxi1 purified by Qiagen tips 100. G418 selection was performed using 300 μg ml−1 of active drug (Sigma).

To evaluate MXI1 expression after transfection in U87 cells MXI1 cDNA was amplified for 35 cycles with primers MXI1-A1 and MXI1-R2b (CATGCTGGGTTCTATGAAGAG) 10/50 μl of PCR mix were loaded. β-actin was amplified for 25 cycles with primers ß-Act-F2, ACCAACTGGGACGACATGGA and β-Act-R2, GTGGTGGTGAAGCTGTAGC and 5/50 μl of PCR mix loaded together with MXI1 amplified from the same RNA. After agarose gel electrophoresis the amount of DNA loaded and the MXI1/actin ratio was evaluated using a Kodak DC40 camera and the Kodak Digital Science 1D software (Scientific Imaging System, New Haven, CT, USA).

In vitro experiments

The proliferation assay was performed on wild-type, Mxi1.22 and Mxi1.14 clones. 5–10×103 cells have been plated in quintuplicate in a 96 well culture plate. One μCi of [3H]-thymidine in 100 μl of culture medium (EMEM) was added to each well 3–4 h after seeding the cells. After 24 h a semi-automated cell harvesting apparatus was used to lyse cells with water and precipitate the labelled DNA on glass fibre filters. Filter pads were dried and counted in a liquid scintillation beta-counter. The proliferation rate was calculated as fold increases over the value obtained on day 1. For the cell counting assay the cells have been transfected with a plasmid carrying a wild-type Mxi1 cDNA both in sense or antisense orientations. After a selection with 300 μg ml−1 of G418 for 2 weeks 2×103 were plated in triplicate in a 24-well culture plate. Cell counting was performed for the subsequent 4 days by Trypan blue staining. To test colony-forming ability 2×102 transfected cells, coming from the same selection as above, were plated in triplicate in a 100 mM culture plate. After 3 weeks the medium was removed and colonies were stained with methylene blue 0.06% and glutaraldehyde 1.25% in Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution.

In vivo experiments

Three groups of athymic ‘nude’ mice (females, 20–25 g, Charles River) were used. Six mice were inoculated subcutaneously in one flank with U87 wild-type cells, six with U87.Mxi1.22 cells and 11 with U87.Mxi1.14 cells. All inoculations consisted of 5×105 cells resuspended in 100 μl of PBS. The tumour size was defined by calculating the major diameters with a caliper. The major diameters were multiplied and values given in mm2.

Cell cycle analysis

For each sample 104 events were analyzed by an Epics cytofluorimeter (Coulter). The cells were stained by propidium iodide (0.1 mg ml−1) and RNase (150 U ml−1) was added after permeabilization in PBS with 0.2% Triton X. DNA content and cell cycle distribution were determined using a computer-assisted analysis.

Northern blot analysis

Total RNAs were extracted by the guanidinium thiocynate/phenol procedure (Sambrook et al, 1989) from U87 wt, U87.Mxi1.22 and U87.Mxi1.14 cell lines. Aliquots (20 μg) of total RNA were separated on 1% formaldehyde-agarose gel at 50 V for 18 h. Nylon N+ (Qiabrane) filters for Northern analysis were prepared by capillary transfer. Filters were hybridized with the following probes: (i) 1400 bp fragment from human cyclin B1 cDNA obtained by BamHI/HindIII digestion of a pCMX plasmid carrying the entire cyclin B1 cDNA cloned into BamHI/HindIII sites, (ii) 1200 bp fragment from human cyclin A cDNA obtained by BamHI/HindIII digestion of a pCMX plasmid carrying the entire cyclin B1 cDNA cloned into BamHI/HindIII sites, (iii) 740 bp fragment from human MXI1 cDNA obtained by PCR on the pCR3 expression vector carrying MXI1 cDNA, (iv) β-actin (Clontech Laboratories Inc., CA, USA). The hybridization were performed at 42°C in a buffer containing 50% formamide, washed to a final stringency of 0.5×SSC, 0.1% SDS at 65°C and autoradiographed at −80°C. Densitometric analysis of autoradigrams were performed by the Molecular Analyst program (BioRad, CA, USA).

Western blot analysis

Total-cell lysates were loaded and separated by SDS–PAGE (12% polyacrylamide) gel and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose. After staining in 0.2% Ponceau S in 3% TCA, the filter was washed twice in PBS and protein binding sites blocked in 5% non-fat dried milk in PBS. The filter was treated with (i) anti cyclin B1 mouse monoclonal (33 ng ml−1), (ii) cyclin A rabbit polyclonal (33 ng ml−1), (iii) Mxi1 rabbit polyclonal (33 ng ml−1), Hsp70 mouse monoclonal (33 ng ml−1) antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. CA, USA). After four washes in TBS (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9) the filter was incubated with the secondary antibody (anti-mouse Ig) conjugated with peroxidase, in 3% BSA/TBS for 1 h at room temperature. The filter was washed four times as above and Western blots were developed using the ECL procedure (Roche, Little Chalfont, UK).

Transient transfections and CAT assay

U87, U87.Mxi1.22 and U87.Mxi1.14 cell lines were cultured in Eagle's medium (EMEM) supplemented with 10% foetal calf serum. DNA transfections were performed using calcium phosphate precipitation (Graham and Van Der Eb, 1973). In each 60 mm plate, 1.5×105 cells were transfected with aliquots of precipitates containing 5 μg of p332B1CAT (Piaggio et al, 1995) or pmE-box332B1CAT (Farina et al, 1996) and 0.5 μg of cytomegalovirus-β-galactosidase (CMV-βgal) plasmid, a control for transfection efficiency. After 16 h, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fresh medium was added. Cells were harvested 48 h after transfection and CAT activity was assayed in whole-cell extract as described (Desvergne et al, 1991). The values were normalized against β-galactosidase activity and protein contents of the extracts.

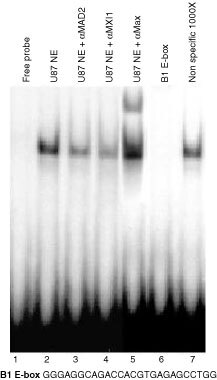

Nuclear extracts and electromobility shift assays

Nuclear extracts from U87 cells were performed as described by Dignam et al (1983). The lysis was performed in the presence of the following protease and phosphatase inhibitors: leupeptin 10 μg ml−1, pepstatin 4 μg ml−1, aprotinin 5 μg ml−1, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate. Electromobility shift assays were performed as described by Miltenberger et al (1995) with the following modifications: (i) oligonucleotide was labelled using the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I, (ii) the reaction was carried out on ice for 30 min and run was performed in 0.5×TBE buffer. In supershift experiments were used 100 ng of anti-Max rabbit polyclonal antibody, 2 μg of anti-Mxi1 rabbit polyclonal antibody, and 2 μg of anti-Mad2 goat polyclonal antibody (all provided by Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The following oligonucleotides were used as probe and competitor (consensus sites are underlined): B1 E-box 5′-GGGAGGCAGACCACGTGAGAGCCTGG; B1up CCAAT: 5′-CCGCAGCCGCCAATGGGAAGGGAGTGA (Farina et al, 1999).

RESULTS

Development of glioblastoma cell lines overexpressing MXI1 cDNA and analysis of their proliferation rate

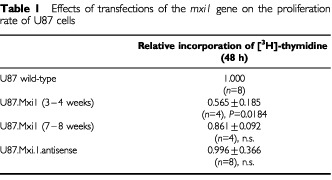

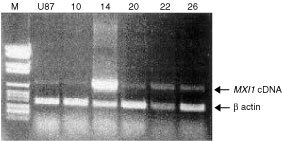

U87 cells, a cell line derived from a human glioblastoma, were stably transfected with a construct carrying MXI1 cDNA. Human MXI1 cDNA was amplified by RT–PCR on lymphocyte RNA and inserted in the eukaryotic expression plasmid pCR3, under the control of the CMV promoter. MXI1 cDNA was also cloned in the antisense orientation, as verified by restriction site analysis and this construct was used for control experiments. Liposome-mediated transfer was used to transfect sense or anti-sense MXI1 cDNAs into U87 cells. Cells transfected by MXI1 cDNA had a decreased [3H]-thymidine incorporation compared to the controls, while cells transfected with antisense cDNA behaved like controls. After 7–8 weeks in culture, however, this negative effect on U87 proliferation decreased significantly (compare data obtained 1 and 2 months after transfection in Table 1). To confirm our observation on a more stable population of transfected cells, 26 clones have been isolated by limiting dilution. Two of these clones showed, respectively, high and low-intermediate levels of MXI1 expression (Figure 1). Clone U87.Mxi1.14 had a MXI1/actin ratio, evaluated by densitometry of RT–PCR products, 18-fold higher than wild-type U87 cells (high level of expression). Clone U87.Mxi1.22 had a MXI1/actin ratio 3.5-fold higher than control (low-intermediate level of expression). The results of [3H]-thymidine incorporation of wild-type and MXI1-transfected U87 clones confirmed that increased Mxi1 expression causes a decreased proliferation rate of glioma cells at different time points. The incorporation rate of U87 wild-type cells, 1 week after seeding, was 2.6 times higher than U87.Mxi1.22 and seven times higher than U87.Mxi1.14, respectively, thus indicating a correlation between the levels of Mxi1 expression and the degree of growth inhibition (Figure 2A).

Table 1. Effects of transfections of the mxi1 gene on the proliferation rate of U87 cells.

Figure 1.

RT–PCR of MXI1 and ß-actin cDNAs in U87 cells wild-type (second lane from left) and transfected by MXI1 cDNA (clones 10, 14, 20, 22 and 26). Molecular weight markers (number VI, Roche) are in the first lane from left. Clones 14 (high MXI1 expression) and 22 (low-intermediate MXI1 expression) were employed in further experiments.

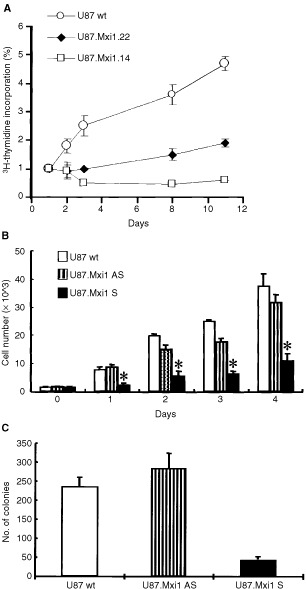

Figure 2.

MXI1 decreases the proliferation rate in vitro of U87 cells. (A) [3H]-thymidine incorporation in U87 wild-type and in Mxi1-transfected clones 22 and 14, with low and intermediate high levels, respectively, of Mxi1 expression. Data are the results of two experiments, and each point was evaluated five times. Values are shown as the folds of increase of [3H]-thymidine incorporation, over day 1. Standard errors are indicated. (B) Cells were transfected with pCR/Mxi1 as reported in Materials and Methods. On day 0, 2×103 cells were plated in triplicate in a 24-wells culture plate and counted after 1, 2, 3 and 4 days. Each point represents the mean±s.d. of three independent experiments. *P<0.05 (Student t-test). (C) 2×102 cells were plated in triplicate in a 100 mm culture plate. After 3 weeks cells were stained and counted as reported in Materials and Methods. Each point represents the mean±s.d. of three independent experiments.

Cell counting and colony forming ability were performed to evaluate the different proliferation rate of cells untransfected or transfected with pCR3/Mxi1 both in sense and antisense orientations. Results are reported in Figure 2B,C and confirm the significant decrease of the proliferation rate of glioma cells overexpressing MXI1. The number of U87/MXI1sense cells 4 days after plating was 30% that of untransfected cells and 35% that of U87/MXI1antisense cells (P<0.05). The number of clones of U87/MXI1sense cells was 25% that of untransfected cells and 22% that of U87/MXI1antisense cells (P<0.02).

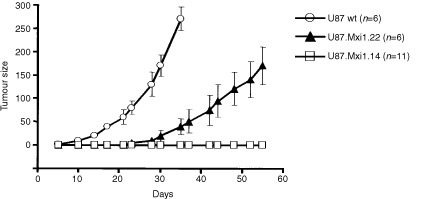

Mxi1 over-expression inhibits tumorigenesis of U87 cells in nude mice

The effects of Mxi1 over-expression were studied in vivo, by subcutaneous grafting in athymic nude mice of U87 wild-type, U87.Mxi1.14 and U87.Mxi1.22 cells (Figure 3). U87.Mxi1.22 tumours appeared later and their size was smaller than controls′ (P=0.0032 to P=0.0001 for comparable time points; t-test, two tails). Strikingly, mice injected with U87.Mxi1.14 cells did not develop any tumour for more than 1 month, after which only one animal showed the appearance of a neoplastic mass. One hundred and twenty days after tumour cell injection, when mice were sacrificed, 10 out of 11 were still tumour-free. These results are consistent with in vitro data, indicating that Mxi1 can act as a suppressor of U87 glioblastomas.

Figure 3.

In vivo growth rate of U87 wild-type and MXI1-transfected cells (clone 22, intermediate MXI1 expression; clone 14, high MXI1 expression) after sub-cutaneous inoculation in nude mice. Tumour sizes, given in mm2, are calculated by multiplying tumour diameters. Standard errors are indicated. Animals with control tumours were sacrificed after 1 month because tumours were too large.

U87 cells with high level of Mxi1 expression accumulate in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle

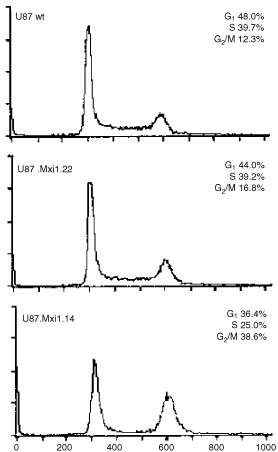

To determine whether Mxi1 inhibits cell proliferation inducing a block in a specific phase of the cell cycle, the DNA content of U87 wild-type, U87.Mxi1.14 and U87.Mxi1.22 cells was measured by flow cytometry. Figure 4 shows that 38.6% of U87.Mxi1.14 cells and 12.3% of wild-type cells, respectively, are in G2/M and that lower amounts of U87.Mxi1.14 cells are in G1 and S phases compared to the wild-type U87 (36.4% vs 48.0% and 25% vs 39.7% respectively). U87.Mxi1.22 cells, on the other hand, only show a little increase of cells in G2/M (16.8% vs 12.3% in wild-type cells), suggesting that Mxi1 effects are partially dose-dependent. These results demonstrate that Mxi1 over-expression in U87 glioblastoma cells leads to an accumulation in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle.

Figure 4.

U87 cells with high level of Mxi1 expression accumulate in the G2/M phases of the cell cycle. FACS analysis shows the DNA content distribution of U87 wild-type, U87 Mxi1.14, and U87 Mxi1.22 cell lines. The percentages of cells in G1, S, and G2/M phases are indicated. X-axes represent the relative fluorescence intensity of propidium iodide-stained cells. Y-axes represent the cell number.

Mxi1 inhibits expression of the cyclin B1 gene

In normal cells, the B-type cyclins (B1, B2, and B3) control the G2/M transition of the cell cycle (Pines and Hunter, 1989; Glotzer et al, 1991). Cyclin B-type proteins interact with the CDK1 during the G2 phase, creating an active complex important for the orderly progression of cell division after DNA synthesis (Draetta et al, 1989; Murray et al, 1989; Pines and Hunter, 1990). Activation of CDK1 only occurs when sufficient cyclin B1 protein has been synthesized (Solomon et al, 1990) and the synthesis of cyclin B1 protein, as for other cyclins, correlates with mRNA accumulation.

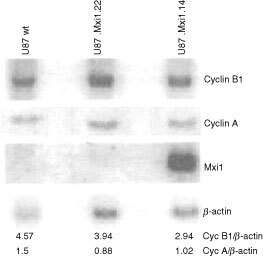

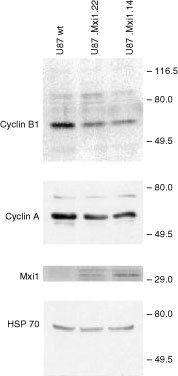

To dissect the molecular mechanism through which Mxi1 induces accumulation in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle, we investigated, in U87 proliferating cells, the expression of cyclin B1 gene and of cyclin A as control. The level of the two cyclin mRNAs was evaluated by Northern blot on RNA of U87.Mxi1.14, U87.Mxi1.22 and U87 wild-type cells. MXI1 and beta-actin transcripts were also analyzed on the same membrane. Figure 5 shows that the amount of cyclin B1 transcript is decreased in U87.Mxi1.14 cells and is similar to wild-type cells in U87.Mxi1.22 cells, while the amount of cyclin A transcript is similar in the three cell population. As evaluated by densitometric analysis, the amount of cyclin B1 transcript is 64% than that of wild-type cells in U87.Mxi1.14 and 86% in U87.Mxi1.22 cells. In agreement with this, immunoblotting analysis of these three cell populations showed that the amount of cyclin B1 protein is decreased in clones 14 and 22 (Figure 6). These data demonstrate that high levels of Mxi1 prevent the accumulation of cyclin B1 mRNA in proliferating U87 cells, suggesting that the cell cycle perturbation induced by Mxi1 over-expression depends on the down-regulation of cyclin B1 expression.

Figure 5.

Mxi1 inhibits expression of the cyclin B1 gene. Northern blot analysis was performed on total RNA extracted from wild-type, Mxi1.22, and Mxi1.14 U87 cell lines. RNAs were size-fractionated on a 1% agarose gel, blotted on a nylon membrane, hybridized with 32P-labelled cyclin B1, cyclin A and MXI1 cDNAs and assessed by autoradiography. Exposure was for 3 h (after overnight exposure the endogenous MXI1 mRNA was visible). To normalize RNA loading, the membrane was re-hybridized with the 32P-labelled cDNA of the housekeeping gene β-actin. The relative intensity of the bands was quantitated by densitometry.

Figure 6.

Cyclin B1 is decreased in Mxi1 transfected U87 cells. Protein extracts from cell lines indicated above each lane were blotted and analyzed by anti cyclin B1, cyclin A, Mxi1, and Hsp70 antibodies. Blotted proteins were in similar amounts, as evaluated by Ponceau staining (not shown).

Transcriptional mechanisms are involved in the inhibition of cyclin B1 expression mediated by Mxi1

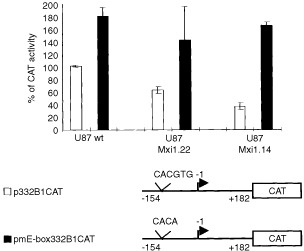

Human cyclin B1 mRNA appears at the end of the S phase and its expression peaks during the G2 phase of the cell cycle (Pines and Hunter, 1989; Piaggio et al, 1995). The transcriptional level of regulation is involved in the induction of expression at the end of the S phase (Cogswell et al, 1995; Hwang et al, 1995; Piaggio et al, 1995; Katula et al, 1997). It has been previously demonstrated that the Upstream Stimulatory Factor (USF), binding the E-box sequence in the promoter of the cyclin B1 gene, is responsible for transcription induction of this gene at the end of the S phase (Cogswell et al, 1995). The same E-box also plays a crucial role as a quiescence responsive element in serum-starved NIH3T3 cells (Farina et al, 1996). We also found that the over-expression of Max protein in proliferating cells leads to down-regulation of the cyclin B1 protein by interacting with the CACGTG E-box located at position −124/−119 in the promoter of the cyclin B1 gene (Farina et al, 1996). Based on these findings we asked whether Mxi1 could modulate the expression of the endogenous cyclin B1 gene directly through the transcriptional inhibition of the cyclin B1 promoter. To answer this question, we transiently transfected U87, U87.Mxi1.22, and U87.Mxi1.14 cells, with plasmids carrying the CAT reporter gene under the control of a cyclin B1 wild-type promoter fragment (p332B1CAT) or a promoter fragment carrying a mutated E-box (pmE-box332B1CAT). The activity of p332B1CAT in U87 wild-type cells was made 100%. As shown in Figure 7, the activity of p332B1CAT decreases to 63% in U87.Mxi1.22 cells and to 36% in U87.Mxi1.14 cells. In contrast, CAT activity of pmE-box332B1CAT does not decrease in Mxi1 over-expressing cells and is similar in the three cell lines. Interestingly, in wild-type cells the activity of the pmE-box332B1CAT is higher than that of p332B1CAT, thus indicating that a negative control of the cyclin B1 promoter activity is lost, at least in part, in the absence of a functional E-box, suggesting a role for endogenous Mxi1. Taken together these results demonstrate that the Mxi1 over-expression in glioblastoma cells inhibits cyclin B1 promoter activity through the E-box in a dose-dependent fashion, suggesting that Mxi1 could directly modulate the expression of the endogenous cyclin B1 gene through transcriptional inhibition.

Figure 7.

Mxi1 inhibits the promoter activity of the cyclin B1 gene. Cyclin B1 promoter CAT-reporter constructs p332B1CAT and pmE-box332 B1CAT (5 μg each) were co-transfected by calcium phosphate in wild-type, Mxi1.22, and Mxi1.14 U87 cell lines along with the CMV-βgal reporter construct (0.5 μg). CAT assay was performed as described (Graham and van der Eb et al., 1973). The values, normalized against β-galactosidase activity, are expressed as percentages of the basal activity (100%) assessed by transfecting p332B1CAT into wild-type U87. Results represent the mean of three independent experiments each performed in duplicate.

Max/Mxi1 heteridimers bind the E-box present on the cyclin B1 promoter

We previously demonstrated that the Max protein recognizes the E-box present on the cyclin B1 promoter (Farina et al, 1996). By EMSAs we verified the ability of Mxi1 to bind the cyclin B1 E-box. Electromobility shift assays, performed with U87 nuclear extracts, reveal one protein complex binding to the radiolabelled probe, spanning nt −133 to −110 in the cyclin B1 promoter (B1 E-box) (Figure 8). A 200-fold molar excess of unlabelled probe (Figure 8, lane 6) specifically inhibits the complex, but not a 1000-fold molar excess of an unrelated probe B1upCCAAT (Farina et al, 1999) containing a CCAAT box sequence (lane 7). Direct evidence of Mxi1 binding was obtained through the use of specific anti-Mxi1 antibodies in the binding reactions. U87 nuclear extracts were pre-incubated with two different antibodies against the Mxi1 protein. As shown in Figure 8, lanes 3 and 4 both Mxi1 antibodies interfere, at least in part, with the formation of the complex. As expected an anti-Max antibody modifies the mobility of the complex (Figure 8, lane 5). In particular, 2 μg of antibodies against the Mxi1 protein are necessary to interfere with the formation of the complex, while only 100 ng of the anti-Max antibody are sufficient to modify the mobility of the complex. This apparent discrepancy could be explained with a different affinity of the antibodies towards two different proteins and towards different functional domain of the proteins. Indeed the antibodies against Mxi1 interfere with the DNA binding, thus indicating that they bind the DNA binding domain of Mxi1 and competition for the binding of the probe. Instead, the anti-Max antibody modifies the mobility of the complex without competition with the binding of Mxi1 to the probe. Neither anti-Mxi1 nor anti-Max antibodies completely interfere with the formation or retard the mobility of the complex. It has been previously demonstrated that USF binds this E-box (Cogswell et al, 1995; Farina et al, 1996), thus the residual molecular complex still occurring in the presence of anti-Mxi1 and anti-Max antibodies could be due to the ability of USF to bind this E-box. Altogether, these results provide evidence that, at least in vitro, Mxi1 recognizes the E-box present on the cyclin B1 promoter.

Figure 8.

Max/Mxi1 heterodimers bind the E-box present on the cyclin B1 promoter. Gel mobility retardation assays were performed with a double-stranded, 32P-labelled oligonucleotide, spanning position −133/−110, containing the E-box of the cyclin B1 promoter (B1 E-box). Addition of nuclear extract from U87 cells resulted in a retarded band. A 200-fold molar excess of unlabelled probe (lane 6) but not an oligonucleotide containing a non-specific binding site (lane 7) specifically inhibits the formation of the complex. In lanes 3, 4, nuclear extracts were pre-incubated with anti-Mxi1 antibodies and, in lane 5, with anti-Max antibody.

DISCUSSION

In the present study we describe one molecular mechanism by which Mxi1 can act as a tumour suppressor in glioblastomas. First, we demonstrate that Mxi1 over-expression causes an inhibition of proliferation of U87 glioblastoma cells in vitro due to an accumulation of the cells in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle. A similar finding was reported by another group (Wechsler et al, 1997). Furthermore, we also demonstrate that Mxi1 over-expression inhibits tumorigenesis of U87 cells in nude mice. This result is in agreement with those coming from MXI1-deficient mice that show increased susceptibility to tumorigenesis (Schreiber-Agus et al, 1998). The investigation of the mxi1 coding sequence in primary glioblastomas does not identify this gene as a major target on chromosome 10q. Indeed SSCP analysis of 36 tumour DNA failed to identify mutations (data not shown).

These data imply that the mechanism through which Mxi1 exerts its tumour suppressor function could be of general interest. We demonstrate here that this mechanism includes the loss of cyclin B1 accumulation through the inhibition of cyclin B1 promoter activity and the possible consequent accumulation of the cells in the G2/M phases of the cell cycle. This G2/M accumulation is of particular interest, considering that over-expression in malignant gliomas of the other Max interactor, Mad1, induces G1/S arrest without obvious perturbations of the G2/M progression (Roussel et al, 1996). This difference and the observation that Mad1 is highly expressed only in non proliferating, post-mitotic cells while Mxi1 is present in cycling cells (Hurlin et al, 1995), suggests that these two proteins affect cell cycle progression at different phases.

In this study we demonstrate that Mxi1 binds the E-box present on the cyclin B1 promoter in vitro and that high levels of Mxi1 inhibit the cyclin B1 promoter activity in an E-box dependent manner in vivo. These results raise the hypothesis that an excess of Mxi1 protein produces an excess of Mxi1/Max heterodimers that may compete with USF for the binding to the E-box of cyclin B1 promoter (Cogswell et al, 1995; Farina et al, 1996). Also in this case the mechanism of action of Mxi1 is different from that of Mad1, since previous results demonstrated that the inhibitory effect of Mad1 on the cyclin B1 promoter is E-box independent (Farina et al, 1996). This diversity confirms that Mxi1 and Mad1 may act during the cell cycle in pathways involving different molecular mechanisms.

In conclusion, we have reported that the molecular mechanism through which Mxi1 can act as an inhibitor of proliferation and tumorigenesis of U87 glioblastoma cells includes the inhibition of cyclin B1 promoter activity through the E-box and the possible consequent loss of cyclin B1 accumulation. Altogether, our results indicate that Mxi1 mediates the down-regulation of cyclin B1 gene expression in malignant gliomas suggesting that this gene is a functional target of the tumour suppressor activity of Mxi1.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Silvia Soddu and Simona Nanni for helpful suggestions, Marco Crescenzi for RNA densitometry analysis and Vincenzo Giusti for computing assistance. Maria Pia Gentileschi for technical advice. I Manni is a recipient of a FIRC fellowship. This work has been supported by grants from Ministero della Sanita', the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC) to G Finocchiaro and G Piaggio.

References

- AlbarosaRColomboBMRozLMagnaniIPolloBCireneiNGianiCFuhrman ContiAMDiDonatoSFinocchiaroG1996Deletion mapping of gliomas suggest the presence of two small regions for candidate tumor-suppressor genes in a 17-cM interval on chromosome 10q Am J Hum Genet 5812601267 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AllandLMuhleRHouJrHPotesJChinLSchreiber-AgusNDePinhoRA1997Role for N-CoR and histone deacetylase in Sin3-mediated transcriptional repression Nature 3874955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AyerDEKretznerLEisenmanRN1993Mad: a heterodimeric partner for Max that antagonizes Myc transcriptional activity Cell 72211222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BlackwellTKKretznerLBlackwoodEMEisenmanRNWeintraubH1990Sequence-specific DNA binding by the c-Myc protein Science 25011491151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ChenJWillinghamTMargrafLRSchreiber-agusNDePinhoRANisenPD1995Effects of the MYC oncogene antagonist, MAD, on proliferation, cell cycling and the malignant phenotype of human brain tumour cells Nature Medicine 1638643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CogswellJPGodlevskiMMBonhamMBisiJBabissL1995Upstream stimulatory factor regulates expression of the cell cycle-dependent cyclin B1 gene promoter Mol Cell Biol 1527822790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DangCVMcGuireMBuckmireMLeeWM1989DNA-binding domain of human c-Myc produced in Escherichia coli Nature 3376646662645525 [Google Scholar]

- DesvergneBPettyKJNikodemVM1991Functional characterization and receptor binding studies of the malic enzyme thyroid hormone response element J Biol Chem 26610081013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DraettaGLucaFWestendorfJBrizuelaLRudermanJBeachD1989Cdc2 protein kinase is complexed with both cyclin A and B: evidence for proteolytic inactivation of MPF Cell 56829838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EdelhoffSAyerDEZervosASSteingrimssonEJenkinsNACopelandNGEisenmanRNBrentRDistecheCM1994Mapping of two genes encoding members of a distinct subfamily of MAX interacting proteins: MAD to human chromosome 2 and mouse chromosome 6, and MXI1 to human chromosome 10 and mouse chromosome 19 Oncogene 9665668 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DignamJDLebovitzRMRoederRG1983Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei Nucl Acids Res 1765456551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FarinaAGaetanoCCrescenziMPucciniFManniISacchiAPiaggioG1996The inhibition of cyclin B1 gene transcription in quiescent NIH3T3 cells is mediated by an E-box Oncogene 1312871296 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FarinaAManniIFontemaggiGTiainenMCenciarelliCBelloriniMMantovaniRSacchiAPiaggioG1999Down-regulation of cyclin B1 gene transcription in terminally differentiated skeletal muscle cells is associated with loss of functional CCAAT-binding NF-Y complex Oncogene 1828182827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FoleyKPEisenmanRN1999Two MAD tails: what the recent knockouts of Mad1 and Mxi1 tell us about the MYC/MAX/MAD network Biochim Biophys Acta 313747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FultsDPedoneC1993Deletion mapping of the long arm of chromosome 10 in glioblastoma multiform Genes Chromosomes Cancer 7173177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GlotzerMMurrayAWKirshenerMW1991Cyclin is degraded by the ubiquitin pathway Nature 349132138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GrahamFLVan Der EbAJ1973A new technique for the assay of infectivity of human adenovirus 5 DNA Virology 52456467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HassigCAFleischerTCBillinANSchreiberSLAyerDE1997Histone deacetylase activity is required for full transcriptional repression by mSin3A Cell 89341347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HenrikssonMLuscherB1996Proteins of the Myc network: essential regulators of cell growth and differentiation Adv Cancer Res 68109182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HurlinPJQuevaCKoskinenPJSteingrimssonEAyerDECopelandNGJenkinsNAEisenmanNE1995Mad3 and Mad4: novel Max-interacting transcriptional repressors that suppress c-myc dependent transformation and are expressed during neural and epidermal differentiation EMBO J 1456465659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HwangAMaityAMcKennaWGMuschelRJ1995Cell cycle-dependent regulation of the cyclin B1 promoter J Biol Chem 2702841928424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KatulaKSWrightKLPaulHSurmanDRNuckollsFJSmithJWTingJPYatesJCogswellJP1997Cyclin-dependent kinase activation and S-phase induction of the cyclin B1 gene are linked through the CCAAT elements Cell Growth Differ 8811820 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KretznerLBlackwoodEMEisenmanRN1992Myc and Max proteins possess distinct transcriptional activities Nature 359426429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LahertyCDYangWMSunJMDavieJRSetoEEisenmanRN1997Histone deacetylases associated with the mSin3 corepressor mediate mad transcriptional repression Cell 89349356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeeTCZiffEB1999Mxi1 is a repressor of the c-Myc promoter and reverses activation by USF J Biol Chem 8595606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MiltenbergerRJSukowKAFarnhamPJ1995An E-box-mediated increase in cad transcription at the G1/S-phase boundary is suppressed by inhibitory c-Myc mutants Mol Cell Biol 1525272535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MurrayAWSolomonMJKirshnerMW1989The role of cyclin synthesis and degradation in the control of maturation promoting factor activity Nature 339280285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PiaggioGFarinaAPerrottiDManniIFuschiPSacchiAGaetanoC1995Structure and growth-dependent regulation of the human cyclin B1 promoter Exp Cell Res 216396402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PinesJHunterT1989Isolation of a human cyclin cDNA: evidence for cyclin mRNA and protein regulation in the cell cycle and for interaction with p34cdc2 Cell 58833846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PinesJHunterT1990p34cdc2: the S and M kinase? New Biol 2389401 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RaoGAllandLGuidaPSchreiber-agusNChenKChinLRochelleJMSeldinMFSkoultchiAIDePinhoRA1996Mouse Sin3A interacts with and can functionally substitute for the amino-terminal repression of the Myc antagonist Mxi1 Oncogene 1211651172 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RasheedBKFullerGNFriedmanAHBignerDDBignerSH1992Loss of heterozygosity for 10q loci in human gliomas Genes Chromosomes Cancer 57582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RousselMFAsnmunRASherrCJEisenmanRNAyerDE1996Inhibition of cell proliferation by the Mad1 transcriptional repressor Mol Cell Biol 1627962801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SambrookJFritschEFManiatisT1989Molecular Cloning. A Laboratory ManualCold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber-AgusNChinLChenKTorresRRaoGGuidaPSkoultchiAIDePinhoRA1995An amino-terminal domain of Mxi1 mediates anti-Myc oncogenic activity and interacts with a homologue of the yeast transcriptional repressor SIN3 Cell 80777786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber-AgusNMengYHoangTHouJrHChenKGreenbergRCordon-CardoCLeeHDePinhoRA1998Role of Mxi1 in ageing organ systems and the regulation of normal and neoplastic growth Nature 393483487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SolomonMJGlotzerMLeeTHPhilippeMKirschnerMW1990Cyclin activation of p34cdc2 Cell 6310131034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WechslerDSShellyCAPetroffCADangCV1997MXI1, a putative tumor suppressor gene, suppresses growth of human glioblastoma cells Cancer Res 5749054912 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZervosASGyurisJBrentR1993Mxi1, a protein that specifically interacts with Max to bind Myc-Max recognition sites Cell 72223232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]