Abstract

Reactive hyperaemia is the increase in blood flow following arterial occlusion. The exact mechanisms mediating this response in skin are not fully understood. The purpose of this study was to investigate the individual and combined contributions of (1) sensory nerves and large-conductance calcium activated potassium (BKCa) channels, and (2) nitric oxide (NO) and prostanoids to cutaneous reactive hyperaemia. Laser-Doppler flowmetry was used to measure skin blood flow in a total of 18 subjects. Peak blood flow (BF) was defined as the highest blood flow value after release of the pressure cuff. Total hyperaemic response was calculated by taking the area under the curve (AUC) of the hyperaemic response minus baseline. Infusates were perfused through forearm skin using microdialysis in four sites. In the sensory nerve/BKCa protocol: (1) EMLA® cream (EMLA, applied topically to skin surface), (2) tetraethylammonium (TEA), (3) EMLA® + TEA (Combo), and (4) Ringer solution (Control). In the prostanoid/NO protocol: (1) ketorolac (Keto), (2) NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME), (3) Keto + l-NAME (Combo), and (4) Ringer solution (Control). CVC was calculated as flux/mean arterial pressure and normalized to maximal flow. Hyperaemic responses in Control (1389 ± 794%CVCmax s) were significantly greater compared to TEA, EMLA and Combo sites (TEA, 630 ± 512, P = 0.003; EMLA, 421 ± 216, P < 0.001; Combo, 201 ± 200, P < 0.001%CVCmax s). Furthermore, AUC in Combo (Keto + l-NAME) site was significantly greater than Control (4109 ± 2777 versus 1295 ± 368%CVCmax s). These data suggest (1) sensory nerves and BKCa channels play major roles in the EDHF component of reactive hyperaemia and appear to work partly independent of each other, and (2) the COX pathway does not appear to have a vasodilatory role in cutaneous reactive hyperaemia.

After a period of arterial occlusion there is a marked increase in blood flow to the ischaemic tissues (Patterson, 1956; Blair et al. 1959; Kilbom & Wennmalm, 1976; Nowak & Wennmalm, 1979; Larkin & Williams, 1993). This transient rise in blood flow is termed reactive hyperaemia and is believed to be caused in part by myogenic relaxation of the vessels (Patterson, 1956; Blair et al. 1959) and by release of local mediators and metabolites from the ischaemic tissues (Kilbom & Wennmalm, 1976; Nowak & Wennmalm, 1979). Although the exact mechanisms of this increased blood flow after a period of ischaemia in the skin microcirculation are not fully understood, one study has shown that sensory nerves are partially involved (Larkin & Williams, 1993).

Larkin & Williams (1993) demonstrated that blocking sensory nerves using local anaesthesia reduces the reactive hyperaemic response in the skin microcirculation of healthy adults. However, the specific neurotransmitters and the endothelial component have yet to be fully revealed. Studies have shown that, in addition to NO and the cycloxygenase (COX) pathways, endothelium derived hyperpolarizing factors (EDHFs) can cause relaxation of blood vessels (Bauersachs et al. 1994; Nelson & Quayle, 1995; Christ et al. 1996; Inokuchi et al. 2003). Despite recent research investigating EDHFs as a class of vasodilating substances, the identity in each vascular bed involved in specific vascular responses remains to be identified. Likely EDHF candidates include epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs), potassium ions, gap junctions and hydrogen peroxide (Bauersachs et al. 1994). In general terms, the hyperpolarizing mechanisms of EDHFs involve an increase in the intracellular calcium concentration due to endothelial receptor activation, which stimulates calcium-activated potassium channels (KCa), hyperpolarizing endothelial cells (Nelson & Quayle, 1995). Evidence suggests that EDHFs move from endothelial cells to vascular smooth muscle cells via myoendothelial gap junctions (Christ et al. 1996). To date, no studies have investigated the role of EDHFs in human skin.

It is well established that the other major endothelial-derived factors, nitric oxide (NO) and metabolites of the cycloxygenase (COX) pathway (prostacyclin; PGI2), have significant vasorelaxive roles in the skin. In terms of cutaneous reactive hyperaemia, evidence suggests that NO does not directly mediate this response (Binggeli et al. 2003; Wong et al. 2003). That is, blockade of NO synthase did not attenuate the rise in skin blood flow during reactive hyperaemia. Consistent with these findings, it was subsequently demonstrated that after arterial occlusion, reactive hyperaemia occurred in the skin by mechanisms that did not result in a measurable increase in NO concentrations (Zhao et al. 2004).

Although prostaglandins are potent vasodilators, their role in the skin vasculature after a period of arterial occlusion remains unclear. In fact, there have been conflicting results about the contribution of prostaglandins to reactive hyperaemia in the cutaneous circulation. One study suggested that vasodilating prostaglandins are major mediators of the cutaneous vasodilator response during reactive hyperaemia (Binggeli et al. 2003), while another study claims that prostaglandins do not play a role in the post-occlusive hyperaemic response in human skin (Dalle-Ave et al. 2004). Recently, findings from Medow et al. (2007) showed that COX blockade resulted in a greater reactive hyperaemic response compared to control sites in the cutaneous vasculature, and suggested that this augmented hyperaemia was NO dependent. More research investigating prostaglandins and reactive hyperaemia in the skin is necessary to provide additional insight into the potential roles of NO and prostaglandins.

The purpose of the present investigation was twofold. First, we sought to investigate the contributions of the large conductance calcium activated potassium (BKCa) channels in the EDHF-mediated component of skin vasodilatation and to identify a potential interaction between the BKCa channels and the neural component of skin vasodilatation. We hypothesized that inhibition of BKCa channels would decrease the reactive hyperaemic response in the cutaneous circulation, and further, combined blockade of BKCa channels and sensory nerves would decrease the reactive hyperaemic response. Second, we examined the individual and combined effects of NO and the COX-pathway in the skin vasodilatation caused by temporary arterial occlusion using microdialysis for drug delivery. To this end, we tested the hypothesis that individual and combined blockades of NO synthase and the COX pathway would not decrease the reactive hyperaemic response in the skin vasculature.

Methods

Subjects

Prior to participation, each subject gave written informed consent as set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Oregon. A total of 18 subjects (9 males and 9 females) participated in these studies (23.2 ± 1 years). All subjects were healthy, did not have high blood pressure or diabetes, had no history of cardiovascular disease and were not taking any medications except for oral contraceptives. To minimize hormonal effects, females were studied during the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle or during the placebo phase if taking oral contraceptives.

Subject monitoring

Studies were performed in an air-conditioned laboratory (21–24°C) with the subjects in a supine position and the experimental arm extended to the side at heart level. Electrocardiogram and blood pressure were monitored continuously throughout the entire experiment (Cardiocap, Datex Ohmeda, Tewksbury, MA, USA). In order to rule out changes in red blood cell (RBC) flux due to pressure changes, subject's blood pressures were measured via auscultation (in the non-experimental arm) during the peak hyperaemic response as well as every 5–7 min throughout the entire protocol.

Skin blood flow measurement

As an index of skin blood flow (SkBF), RBC flux was measured by using non-invasive laser-Doppler flowmetry (moorLab, Moor Instruments, Devon, UK). A total of four integrated probes were used in each protocol, in conjunction with local heaters, to continuously monitor RBC flux at each site.

Specific protocols

BKCa channel/sensory nerve protocol

The purpose of this protocol was to study the separate and combined effects of tetraethylammonium (TEA, BKCa channel blocker) (Inokuchi et al. 2003) and EMLA® cream (nerve blockade) (Larkin & Williams, 1993) in the cutaneous circulation after 5 min of arterial occlusion. Four microdialysis fibres (MD 2000, Bioanalytical Systems West Lafayette, IN, USA) with a membrane length of 10 mm were placed at least 5 cm apart in the forearm skin of the left arm of 10 subjects. Placement of the microdialysis fibres was achieved by inserting a 25-gauge needle through the skin with entry and exit points ∼2.5 cm apart. The microdialysis fibre was then threaded through the lumen of the needle. The needle was withdrawn from the skin, leaving the microdialysis membrane in place

One site was perfused with 50 mm tetraethylammonium (TEA; Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA) dissolved in Ringer solution. At another site, EMLA® cream (Astra, Westborough, MA, USA) was applied to approximately 4 cm2 of an area of the skin. A third site was used to study the combined effects of 50 mm TEA and EMLA® (‘Combo’) and the fourth site served as a control site and was continuously perfused with Ringer solution at a rate of 2 μl min−1. All of the microdialysis sites were randomized. TEA was chosen as the blocker as it is selective for BKCa channels and can be used in humans. Other blockers of the BKCa channels, charybdotoxin and iberiotoxin, are too toxic for human application (Pickkers et al. 1998), and, in the case of charybdotoxin is not selective to only the BKCa channels (Feletou & Vanhoutte, 2006). The TEA concentration used was determined from pilot work in our lab in which we occluded the arm for 5 min and observed the responses using different concentrations of the BKCa blocker. We chose the lowest TEA concentration where any further increases in concentration resulted in no further inhibition of the response. Specifically, we performed 5 min reactive hyperaemias at 0.25, 2.5, 25, 50 and 100 mm TEA in a total of eight subjects. We observed that above 50 mm, the reactive hyperaemic response was not further decreased.

Approximately 30 min after needle insertion, infusion of 50 mm TEA began in two sites (‘TEA only’ and ‘Combo’) and lasted for the remainder of the protocol. At the same time, EMLA® cream was applied in two sites (‘EMLA only’ and ‘Combo’) for 1 h. Following this, those sites were wiped off and a new amount of EMLA® cream was applied for another 30 min to ensure complete sensory blockade. Therefore, a period of 2 h passed between the needle insertions and the beginning of baseline recording.

At the end of the 2 h period, integrated laser-Doppler probes were placed directly over the microdialysis membranes to continuously measure RBC flux. A stable 10 min baseline was recorded before the first arterial occlusion. Arterial occlusions with the resulting reactive hyperaemias were performed three times with a 15 min recovery period between each occlusion. Following the third arterial occlusion and reactive hyperaemia, RBC flux was allowed to return to baseline values, after which maximal RBC flux was achieved by increasing the temperature of the local heating units to 44°C and by infusing 28 mm sodium nitroprusside (SNP; Nitropress, Ciba Pharmaceuticals). We have previously determined that this combination results in maximal dilatation of skin sites in which ketorolac has been administered (McCord et al. 2006).

Ketorolac/l-NAME protocol

The purpose of this protocol was to further examine whether the COX pathway and NO are involved in the cutaneous circulation after 5 min of arterial occlusion. Four microdialysis fibres (MD 2000, Bioanalytical Systems) with a membrane length of 10 mm were placed at least 5 cm apart in the forearm skin of the left arm of eight subjects using the same technique as the previous protocol.

One site was perfused with 10 mm ketorolac (Keto; Sigma-Aldrich, Inc.) dissolved in Ringer solution. Another site was perfused with 10 mmNG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA). A third site was used to study the combined effects of 10 mm Keto and 10 mm l-NAME final dilution and the fourth site served as a control site (Ringer solution). All sites were perfused at a rate of 2 μl min−1. Numerous studies have shown that 10 mm Keto and 10 mm l-NAME adequately inhibit COX (Holowatz et al. 2005; McCord et al. 2006) and NO synthase (Kellogg et al. 1998; Wong et al. 2004; Holowatz et al. 2005; McCord et al. 2006) in the skin, respectively. All of the microdialysis sites were randomly assigned to minimize either site location bias (i.e. proximal versus distal sites) or laser probe bias.

After the needle insertion, drug infusion in all four sites began and lasted for the remainder of the protocol. A period of 75–90 min allowed the insertion trauma response to resolve. Following this, integrated laser-Doppler probes were placed directly over the microdialysis membranes to continuously measure RBC flux. Skin sites were monitored continuously until a stable 10 min baseline was recorded before the first arterial occlusion. Arterial occlusions with the resulting reactive hyperaemia were performed twice with a 15 min recovery period between each occlusion. The average of both occlusions was used for further analysis. Following the second arterial occlusion and reactive hyperaemia, RBC flux was allowed to return to baseline values, after which maximal RBC flux was achieved by increasing the temperature of the local heating units at a rate of 0.5°C every 5 s to up to 44°C and by infusing 28 mm SNP.

Data analysis

Data were digitized and saved on a personal computer at 40 Hz using Windaq data acquisition software (Dataq Instruments, Akron, OH, USA). Data were analysed off-line using signal-processing software. RBC flux values from the laser-Doppler units were divided by mean arterial pressure (MAP) to yield a value of cutaneous vascular conductance (RBC flux/MAP = CVC). RBC flux values were then calibrated to 0 during the period of arterial occlusion and 100 during maximal blood flow (SNP infusion and local heating to 44°C). Expression of data in this manner takes into account any changes in blood flow due to changes in blood pressure and also better reflects absolute changes in SkBF. Thus, data are presented as a percentage of maximal CVC (%CVCmax).

Calculations and statistical analysis

Peak blood flow was defined as the highest blood flow value after release of the pressure cuff, and values were expressed as percentage CVCmax. The total hyperaemic response was calculated by taking the area under the curve (AUC) of the hyperaemic response. Baseline SkBF values before arterial occlusion were then multiplied by the time it took for the blood flow to return to baseline levels from the time the pressure cuff was released. This value was subsequently subtracted from the value obtained for the AUC (i.e. total hyperaemic response = AUC – (baseline SkBF as percentage CVCmax× duration of hyperaemic response in seconds); Wong et al. 2003). Thus, differences in baseline between subjects or between the different sites were accounted for, and the total hyperaemic response was evaluated with regard to the increase in SkBF above baseline. Data for the total hyperaemic response were expressed as percentage CVCmax seconds.

For a given trial and occlusion time period, the two most consistent responses for each subject were averaged for subsequent analysis. In the ‘EMLA’ and ‘Combo’ sites, however, only the first reactive hyperaemia was used for further calculations because we consistently observed that each reactive hyperaemia was larger than the previous one during the protocol. We suspect that the sensory nerve blockade by the EMLA® cream was wearing off and that is why the size of each reactive hyperaemia increased with time. However, we are confident that during the first trial we had the highest degree of blockade. After EMLA® cream was removed, each site was tested for any sensation by pinprick without the subject knowing which site was being tested. We observed that in the EMLA® sites there was a complete loss of sensation when compared to the other sites, and thus sensory nerves were adequately blocked at the time of the first reactive hyperaemia.

In the ketorolac/l-NAME protocol we observed that in 2 out of the 8 subjects the reactive hyperaemic response in the Combo site took a considerably longer time (> 800 s) to return to baseline values so we used the first 500 s for further statistical analysis (the average reactive hyperaemic response in the Combo site was ∼400 s).

Data from each of the protocols were compared by using a one-way, repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's analysis for post hoc comparisons. Significance for both protocols was set at P < 0.05, and values are expressed as percentage CVCmax± s.d.

Results

BKCa/sensory nerve protocol

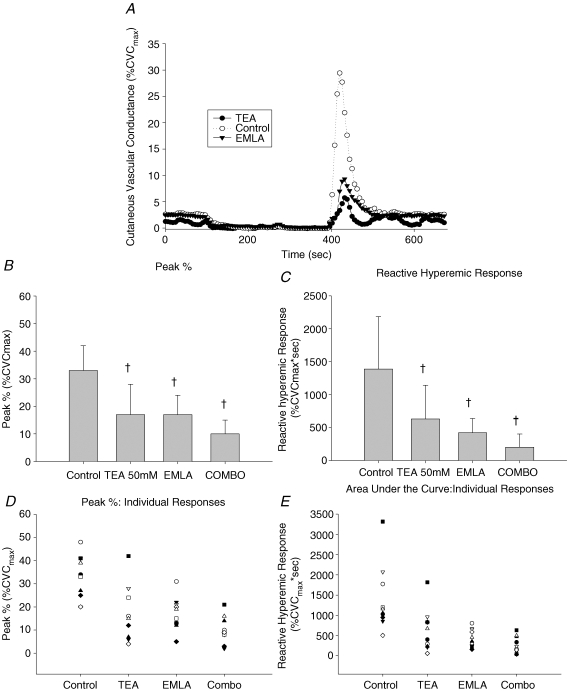

Figure 1 displays a representative tracing, mean ± s.d., and individual data from the BKCa/sensory nerve protocol. Figure 1A is a representative tracing of the SkBF response to a 5 min blood flow occlusion and depicts the baseline, occlusion time, peak blood flow, and the resulting reactive hyperaemic response (Control, TEA and EMLA).

Figure 1.

BKCa/sensory nerve protocol A, representative reactive hyperaemia tracing during measurement of laser Doppler flowmetry expressed as percentage CVCmax (Control, TEA and EMLA sites). B, means and standard deviations for the peak CVC. There was a significant reduction in the peak CVC values in all of the experimental sites (TEA, EMLA and Combo) when compared to the control site (Control; all P < 0.001). C, means and standard deviations for the reactive hyperaemic response (AUC). All experimental sites (TEA, EMLA and Combo) were significantly reduced compared to the control site (Control; all P < 0.005). D, individual responses to the peak response. E, individual responses to the reactive hyperaemic response. †Significantly different from the Control site.

Figure 1B represents the peak CVC values after individual and combined use of TEA and EMLA® cream. There was a significant reduction in the peak CVC values in all of the experimental sites (TEA, 16.8 ± 11.3%CVCmaxP < 0.001; EMLA, 17.3 ± 6.8%CVCmax, P < 0.001; Combo, 9.8 ± 5.5%CVCmax, P < 0.001) when compared to the control site (32.7 ± 9.4%CVCmax). Neither TEA alone nor EMLA alone was significantly different from Combo (P = 0.175 and P = 0.149, respectively). The lack of statistical significance is primarily due to fact that in half the subjects TEA alone and/or EMLA alone reduced the peak CVC during reactive hyperaemia by 70–95% when compared to the control site (coefficient of variation: Control, 28.7%; EMLA, 39.5%; TEA, 67.6%; Combo, 55.6%). Sample size calculations determined that it would require approximately 30 subjects to achieve statistical significance.

Figure 1C depicts the differences in the AUC after individual and combined inhibition of sensory nerves and BKCa channels. Neither TEA nor EMLA® cream altered the baseline SkBF values. All experimental sites (TEA, 630 ± 512%CVCmax s, P = 0.003; EMLA, 421 ± 216%CVCmax s, P < 0.001; Combo, 201 ± 200%CVCmax s, P < 0.001) were significantly reduced compared to the control site (1389 ± 794%CVCmax s). Again, statistical significance was not achieved between the individually blocked and Combo-blocked sites. However, although there was some variability in the Combo site, in some of the subjects the reactive hyperaemia response was completely abolished. Figure 1D and E illustrates the individual responses to the peak response and individual responses to the reactive hyperaemic response, respectively (coefficient of variation: Control, 57.2%; EMLA, 51.2%; TEA, 81.2%; Combo, 99.6%).

Ketorolac/l-NAME protocol

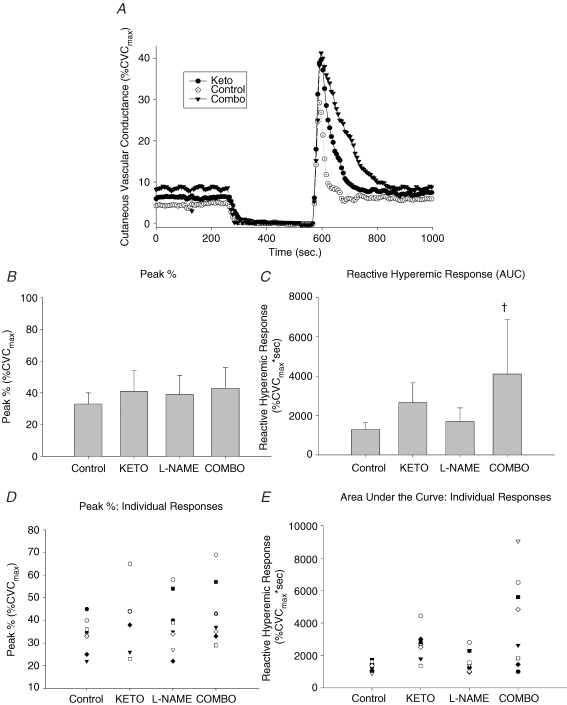

Figure 2 displays a representative tracing, mean ± s.d., and individual data from the prostanoids/NO-inhibition protocol. Figure 2A is a representative tracing of the SkBF response to a 5 min blood flow occlusion and depicts the baseline, occlusion time, peak blood flow and the resulting reactive hyperaemic response (Control, Keto and Combo). Figure 2B represents the peak blood flows after the release of arterial occlusions. There was no statistically significant difference between any of the sites (Control, 33.4 ± 7.5%CVCmax; Keto, 40.7 ± 12.8%CVCmax; l-NAME, 38.5 ± 11.8%CVCmax; Combo, 43.1 ± 13.3%CVCmax; coefficient of variation: Control, 22.3%; Keto, 31.5%; l-NAME, 30.5%; Combo, 30.8%).

Figure 2.

Ketorolac/l-NAME protocol A, representative reactive hyperaemia tracing during measurement of laser Doppler flowmetry expressed as percentage CVCmax (Control, Keto and Combo sites). B, means and standard deviations for the peak CVC. C, means and standard deviations for the reactive hyperaemic response (AUC). Ketorolac (Keto) had a significant increase in the AUC compared to Control. D, individual responses to the peak response. E, individual responses to the reactive hyperaemic response. †Significantly different from the Control site.

Figure 2C displays the total reactive hyperaemic response (AUC). Neither ketorolac nor l-NAME altered the baseline SkBF values. The AUC in the Combo site (4109 ± 2775%CVCmax s) was significantly larger than the AUC in the control site (1295 ± 368%CVCmax s). l-NAME had no effect on the AUC (1697 ± 691%CVCmax s) and, although not statistically significant due to the very large variability, there was a trend towards an increase of the AUC in the Keto site compared to the control site (2658 ± 1007%CVCmax s; coefficient of variation: Control, 28.4%; Keto, 37.9%; l-NAME, 40.7%; Combo, 67.5%).

Figure 2D and E illustrates the individual responses to the peak response and individual responses to the reactive hyperaemic response, respectively.

Discussion

The major findings of this study are as follows. First, sensory nerves and BKCa channels play major roles in reactive hyperaemia in the cutaneous circulation. Second, the COX pathway does not appear to play a vasodilatory role in the cutaneous reactive hyperaemia response.

Contribution of sensory nerves and BKCa channels to reactive hyperaemia

To our knowledge, there have been no published studies investigating the role of BKCa channels in human skin. Our results from the BKCa/sensory nerve protocol were consistent with our hypothesis, suggesting that the hyperpolarizing mechanism by which smooth muscle cells relax after a period of arterial occlusion seems to involve BKCa channels. Our observation that BKCa channels are involved in cutaneous reactive hyperaemia suggests that the hyperpolarization of endothelial cells might be partly regulated by the activation of the cytochrome P450 enzyme (CYP450), as it has been suggested that metabolites of this enzyme involve epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) which elicit smooth muscle relaxation by opening BKCa channels (Komori & Vanhoutte, 1990). Studies have shown that stimuli like bradykinin, pulsatile stretch and shear stress activate the CYP450 pathway and release EETs, which then diffuse to smooth muscle cells and open BKCa channels, resulting in a hyperpolarization (Campbell et al. 1996; Fichtlscherer et al. 2004; Huang et al. 2005). In apparent contrast to our findings, some animal studies (Chataigneau et al. 1998; Yamanaka et al. 1998) and a human study investigating the cerebral artery (Petersson et al. 1997) showed that BKCa channels are not involved in the EDHF-mediated reactive hyperaemic response. These discrepancies may be explained by differences between species, the specific vascular bed, or the type of vessel studied. Therefore, the mechanisms underlying the EDHF-mediated vasodilatation in reactive hyperaemia need further study.

Our observation that sensory nerve blockade decreased the skin reactive hyperaemic response agrees with a study done by Larkin & Williams (1993), who found that local anaesthesia can significantly inhibit reactive hyperaemia in the cutaneous circulation. We further investigated this pathway by combining sensory nerve blockade with inhibition of the BKCa channels. The release of neuropeptides or other substances from the sensory nerves in the skin may partially account for the EDHF component of the skin vasodilatation. In agreement with our results, a study done by Inokuchi et al. (2003) suggested that intra-arterial infusion of TEA significantly decreased the human forearm vasodilatation evoked by substance P and bradykinin. Therefore, neuropeptides released from sensory nerves could partially account for the activation of BKCa channels in smooth muscle cells. However, the specific nerve population involved and the specific substances released from the sensory nerves are not able to be determined in this study as EMLA is a general Na+ channel blocker. It has been shown that the adrenergic vasoconstrictor nerves are not involved in the reactive hyperaemic response (Schmedtje & Eckberg, 1991), but whether the sudomotor/cholinergic nerves are involved remains to be determined. We also found that the combination of BKCa channel and sensory nerve blockade tended to cause a further decrease in both the peak response and the AUC to a greater extent than either treatment alone. Although this could be explained by incomplete blockade of either pathway, an interaction between the vasoactive substance(s) from the sensory nerves and the BKCa channels could take place either within the endothelial cells or inside the smooth muscle cells. The lack of statistical significance between the Combo versus EMLA and Combo versus TEA sites is attributed to the fact that in a number of the subjects we observed a profound reduction in the hyperaemic response to the individual blockades. Figure 1D and E illustrates the individual responses to the different treatment conditions.

Role of prostaglandins and NO in reactive hyperaemia

There have been only a few studies investigating the role of prostaglandins during reactive hyperaemia in human skin and the findings were not consistent. Our observation that COX inhibition did not diminish the peak flow after an arterial occlusion agrees with the results from Dalle-Ave et al. (2004), who found that intravenous administration of 900 mg of lysine acetylsalicylate (equivalent to 500 mg of acetylsalicylic acid) did not attenuate the skin reactive hyperaemia. Contrary to our findings and to those from Dalle-Ave et al. (2004), other studies (Binggeli et al. 2003) found that administration of a similar COX inhibitor significantly reduced reactive hyperaemia in the skin. These discrepancies in findings may be accounted for by the fact that administration of the drug was different. Furthermore, different analyses of the reactive hyperaemic response were employed. For instance, Binggeli et al. (2003) presented their findings as the percentage of baseline change but it was not clear if baseline changes were accounted for in their study. By using the microdialysis technique we were able to administer a relatively high concentration of ketorolac in a small area of the skin, adequately blocking the COX enzyme (Holowatz et al. 2005; McCord et al. 2006). In addition, with laser-Doppler flowmetry we were able to directly measure changes in blood flow that occur only within the skin microcirculation. Therefore, by the utilization of these combined methodologies and expression of values as percentage CVCmax, a more consistent comparison between subjects and between skin sites was achieved. On the basis of this, our results provide evidence that COX inhibition did not reduce CVC during reactive hyperaemia in the cutaneous microvasculature.

Naylor et al. (1999) were the first to suggest that inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis by oral administration of indomethacin can cause an increase in reactive hyperaemia after 5 min of arterial occlusion. In a very recent study in the skin, Medow et al. (2007) reported an increase in all aspects of skin reactive hyperaemia (peak and AUC) after administration of 10 mm ketorolac, also delivered by the microdialysis method. However, our methods and findings do differ from theirs in a few important respects. First, we did not observe a difference in the peak reactive hyperaemic response between the control and Keto treated sites. In a few of our subjects we observed a greater total reactive hyperaemic response, but this was not consistent. In these subjects, CVC did not return to baseline as rapidly as in the control site, and in some subjects this was profoundly delayed. Due to the standard analysis method, this resulted in a greater, but highly variable, total reactive hyperaemic response. This response was even more variable when NO synthase inhibition was combined with COX blockade. In contrast to the findings of Medow et al. (2007), NO synthase did not abolish the COX-mediated augmented vasodilation in these subjects. Although differences may be attributable to the specific NO synthase inhibitor used, both are NO synthase isoform non-specific. An important difference between the two studies is that, in their study, ketorolac was found to profoundly increase baseline skin blood flow, an observation that we have not found in this study or in our previous published studies using ketorolac (Holowatz et al. 2005; McCord et al. 2006) despite using the same types of microdialysis fibres and the same doses of drug. Furthermore, we have previously found that 28 mm sodium nitroprusside alone is not sufficient to achieve maximal vasodilation at the end of a study when ketorolac was used. Thus, we combined the nitroprusside infusion with local heating to 44°C to achieve maximal vasodilation (Holowatz et al. 2005; McCord et al. 2006).

In any case, why the reactive hyperaemic responses are greater and more variable when ketorolac is used is not clear, although our findings do not support the conclusion by Medow et al. that COX blockade unmasks a NO-dependent vasodilation. As it has been demonstrated that there is a neural component to cutaneous reactive hyperaemia, it is possible that stimulation of surface receptors by the agonist(s) lead to a chain of intracellular events, all of which result in increased cytosolic Ca2+. This could then up-regulate NOS and activate phospholipase A2, the enzyme responsible for the production of arachidonic acid from phospholipid precursors. Although the main mechanism through which NO reduces vascular tone is via activation of soluble guanylate cyclase, NO is also capable of up-regulating cyclooxygenase type-1 (COX-1) and type-2 (COX-2) enzymes. An alternative explanation may be that NO and the COX enzyme have an inhibitory effect on the EDHF pathway. Previous studies suggested that the EDHF pathway may normally serve as a backup vasodilator mechanism when NO and prostaglandins are inhibited (Bauersachs et al. 1996; Osanai et al. 2000). Consequently, with the combined blockade of NO and the COX pathway, EDHFs are no longer partially inhibited, and thus an increase in the total reactive hyperaemic response was observed. Based on our current data, the EDHF pathway could possibly be the alternative mechanism responsible for the increased reactive hyperaemia after NO and COX inhibition in the human skin. Overall, we do not believe that the findings of an augmented total reactive hyperaemic response in some subjects can be explained by an artifact due to the specific drug, as we have previously demonstrated that the rise in skin blood flow during whole body heating is diminished by COX inhibition (using two different types of COX inhibitors, including ketorolac), but that the SkBF response to local heating is not affected (McCord et al. 2006).

Limitations

The possibility exists that we were unable to completely block these pathways, although every effort was made to use established doses and to verify adequacy of the blockades. Another prospective limitation to the current study was the inability to eliminate the possibility that the concentrations used disrupted the blood vessel function independent of their specific inhibition, thus preventing the full expression of vasodilatation to a period of arterial occlusion. To minimize the likelihood of these limitations, the drugs used for this study have been carefully researched and dosages were assigned on the basis of pilot work or previous investigations. Despite these efforts, it is possible that the antagonists used did not achieve complete blockade, and thus it is not feasible for us to eliminate the possibility that BKCa channels and/or sensory nerves may play a larger role in the reactive hyperaemia in the cutaneous circulation than observed in the present investigation. In addition, with any pharmacological treatment, there is also the potential for other non-specific interactions of the drugs. That said, it is important to note that in most subjects, the combined blockade of BKCa and the sensory nerves almost completely eliminated the reactive hyperaemia response in a number of subjects.

In conclusion, these data provide evidence supporting a role for the BKCa channels and sensory nerves in the mechanism of reactive hyperaemia in the cutaneous circulation, but do not support a vasodilatory role for the COX pathway.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly appreciate the considerable time and effort of the subjects. Funding for this study was provided by the National Institutes of Health Grant HL-70928.

References

- Bauersachs J, Hecker M, Busse R. Display of the characteristics of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor by a cytochrome P450-derived arachidonic-acid metabolite in the coronary microcirculation. Br J Pharmacol. 1994;113:1548–1553. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauersachs J, Popp R, Hecker M, Sauer E, Fleming I, Busse R. Nitric oxide attenuates the release of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor. Circulation. 1996;94:3341–3347. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.12.3341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binggeli C, Spieker LE, Corti R, Sudano I, Stojanovic V, Hayoz D, Luscher TF, Noll G. Statins enhance postischemic hyperemia in the skin circulation of hypercholesterolemic patients – A monitoring test of endothelial dysfunction for clinical practice? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:71–77. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00505-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair D, Glover WE, Roddie IC. The abolition of reactive and post-exercise hyperemia in the forearm by temporary restriction of arterial inflow. J Physiol. 1959;148:648–658. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1959.sp006313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell WB, Gebremedhin D, Pratt PF, Harder DR. Identification of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids as endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors. Circ Res. 1996;78:415–423. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.3.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chataigneau T, Feletou M, Duhault J, Vanhoutte PM. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, potassium channel blockers and endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization in the guinea-pig carotid artery. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;123:574–580. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ GJ, Spray DC, el-Sabban M, Moore LK, Brink PR. Gap junctions in vascular tissues – Evaluating the role of intercellular communication in the modulation of vasomotor tone. Circ Res. 1996;79:631–646. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalle-Ave A, Kubli S, Golay S, Delachaux A, Liaudet L, Waeber B, Feihl F. Acetylcholine-induced vasodilation and reactive hyperemia are not affected by acute cyclo-oxygenase inhibition in human skin. Microcirculation. 2004;11:327–336. doi: 10.1080/10739680490449268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feletou M, Vanhoutte PM. Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor – Where are we now? Arterioscler Thromb Vascular Biol. 2006;26:1215–1225. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000217611.81085.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fichtlscherer S, Dimmeler S, Breuer S, Busse R, Zeiher AM, Fleming I. Inhibition of cytochrome P450 2C9 improves endothelium-dependent, nitric oxide-mediated vasodilatation in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2004;109:178–183. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000105763.51286.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holowatz LA, Thompson CS, Minson CT, Kenney WL. Mechanisms of acetylcholine-mediated vasodilatation in young and aged human skin. J Physiol. 2005;563:965–973. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.080952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang A, Sun D, Jacobson A, Carroll MA, Falck JR, Kaley G. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids are released to mediate shear stress-dependent hyperpolarization of arteriolar smooth muscle. Circ Res. 2005;96:376–383. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000155332.17783.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inokuchi K, Hirooka Y, Shimokawa H, Sakai K, Kishi T, Ito K, Kimura Y, Takeshita A. Role of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in human forearm circulation. Hypertension. 2003;42:919–924. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000097548.92665.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg DL, Crandall CG, Liu Y, Charkoudian N, Johnson JM. Nitric oxide and cutaneous active vasodilation during heat stress in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1998;85:824–829. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.3.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbom A, Wennmalm A. Endogenous prostaglandins as local regulators of blood-flow in man: effect of indomethacin on reactive and functional hyperemia. J Physiol. 1976;257:109–121. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori K, Vanhoutte PM. Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor. Blood Vessels. 1990;27:238–245. doi: 10.1159/000158815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin SW, Williams TJ. Evidence for sensory nerve involvement in cutaneous reactive hyperemia in humans. Circ Res. 1993;73:147–154. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.1.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord GR, Cracowski J-L, Minson CT. Prostanoids contribute to cutaneous active vasodilation in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R596–R602. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00710.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medow MS, Taneja I, Stewart JM. Cyclooxygenase and nitric oxide synthase dependence of cutaneous reactive hyperemia in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H425–H432. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01217.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor HL, Shoemaker JK, Brock RW, Hughson RL. Prostaglandin inhibition causes an increase in reactive hyperaemia after ischaemic exercise in human forearm. Clin Physiol. 1999;19:211–220. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2281.1999.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Quayle JM. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth-muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1995;37:C799–C822. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.4.C799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak J, Wennmalm A. Study on the role of endogenous prostaglandins in the development of exercise-induced and post-occlusive hyperemia in human limbs. Acta Physiol Scand. 1979;106:365–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1979.tb06411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osanai T, Fujita N, Fujiwara N, Nakano T, Takahashi K, Guan WP, Okumura K. Cross talk of shear-induced production of prostacyclin and nitric oxide in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H233–H238. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.1.H233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson G. The role of intravascular pressure in the causation of reactive hyperemia in the human forearm. Clin Sci. 1956;15:17–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersson J, Zygmunt PM, Hogestatt ED. Characterization of the potassium channels involved in EDHF-mediated relaxation in cerebral arteries. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;120:1344–1350. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickkers P, Hughes AD, Russel FGM, Thien T, Smits P. Thiazide-induced vasodilation in humans is mediated by potassium channel activation. Hypertension. 1998;32:1071–1076. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.6.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmedtje JF, Eckberg DL. Preservation of oscillations in postocclusive reactive hyperemia. J Appl Physiol. 1991;70:363–367. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.70.1.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong BJ, Wilkins BW, Holowatz LA, Minson CT. Nitric oxide synthase inhibition does not alter the reactive hyperemic response in the cutaneous circulation. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:504–510. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00254.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong BJ, Wilkins BW, Minson CT. H1 but not H2 histamine receptor activation contributes to the rise in skin blood flow during whole body heating in humans. J Physiol. 2004;560:941–948. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.071779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka A, Ishikawa T, Goto K. Characterization of endothelium-dependent relaxation independent of NO and prostaglandins in guinea pig coronary artery. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;285:480–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao JL, Pergola PE, Roman LJ, Kellogg DL. Bioactive nitric oxide concentration does not increase during reactive hyperemia in human skin. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:628–632. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00639.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]