Abstract

Sensory neurons represent an attractive target for pharmacological treatment of various bladder disorders. However the properties of major classes of mechano-sensory neurons projecting to the bladder have not been systematically established. An in vitro bladder preparation was used to examine the effects of a range of mechanical stimuli (stretch, von Frey hair stroking and focal compression of receptive fields) and chemical stimuli (1 mm α,β-methylene ATP, hypertonic solutions (500 mm NaCl) and 3 μm capsaicin) during electrophysiological recordings from guinea pig bladder afferents. Four functionally distinct populations of bladder sensory neurons were distinguished by these stimuli. The first class, muscle mechanoreceptors, were activated by stretch but not by mucosal stroking with light (0.05–0.1 mN) von Frey hairs or by hypertonic saline, α,β-methylene ATP or capsaicin. Removal of the urothelium did not affect their stretch-induced firing. The second class, muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors, were activated by both stretch and mucosal stroking with light von Frey hairs or by hypertonic saline and by α,β-methylene ATP, but not by capsaicin. Removal of the urothelium reduced their stretch- and stroking-induced firing. The third class, mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors, were stretch-insensitive but could be activated by mucosal stroking with light von Frey hairs or by hypertonic saline, α,β-methylene ATP and capsaicin. Stroking-induced firing was significantly reduced by removal of the urothelium. The fourth class, mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors, were stretch insensitive but could be weakly activated by mucosal stroking with light von Frey hairs but not by hypertonic saline, α,β-methylene ATP or capsaicin. Removal of the urothelium reduced mucosal stroking-induced firing. All four populations of afferents conducted in the C-fibre range and showed class-dependent differences in spike amplitude and duration. At least four functional classes of bladder mechanoreceptors can be readily distinguished by different mechanisms of activation and are likely to transmit different types of information to the central nervous system.

Spinal sensory neurons projecting from the bladder play a key role in nerve circuits mediating both storage and normal micturition. These neurons are also responsible for sensation from the bladder, ranging from fullness through discomfort to pain. Because of their key role in bladder function and sensation, sensory neurons represent an attractive target for novel pharmacological therapies of various bladder disorders including painful bladder syndrome (interstitial cystitis) and overactive bladder syndrome. Interstitial cystitis is a chronic disease characterized by urinary urgency and frequency, usually with pelvic pain and nocturia, in the absence of bacterial infection or other identifiable pathology. In the USA, it has been estimated that more than 1 000 000 individuals will suffer from interstitial cystitis during their lifetime (Jones & Nyberg, 1997). About 17% of people in the USA and Europe over age of 40 have the clinical syndrome of ‘overactive bladder’, which causes symptoms including urgency, frequency, nocturia, and, in about one-third of patients, urge incontinence (Milsom et al. 2001; Stewart et al. 2003). Urgency is a primary symptom of overactive and painful bladder syndromes; however, the mechanisms underlying this sensation are largely unknown. Understanding the basis of sensation from the bladder requires a systematic account of the different classes of sensory neurons projecting from the organ. The nature of the stimuli detected by different types of bladder afferents should be a component of any such account.

In studies carried out in vivo, bladder afferents have been divided into distension-sensitive mechanoreceptors, distension-insensitive chemoreceptors and silent afferents. Distension-insensitive bladder chemoreceptors could be activated by distension with isotonic KCl but not NaCl (Moss et al. 1997). It is likely that these K+-sensitive endings are located in the mucosal layer, and thus ‘chemoreceptors’ may largely correspond to ‘mucosal receptors’. Eighteen to twenty-eight per cent of bladder afferents do not respond to any level of distension and have been called ‘silent afferents’ (Häbler et al. 1990; Jänig & Koltzenburg, 1993; Cervero, 1994; Shea et al. 2000); some of them may become loosely mechano-sensitive during acute inflammation (Jänig & Koltzenburg, 1993).

Among distension-sensitive bladder afferents, both low threshold and high threshold afferents, conducting in both small myelinated Aδ- and unmyelinated C-fibre ranges, have been identified in vivo (Iggo, 1955; Häbler et al. 1990; Sengupta & Gebhart, 1994; Shea et al. 2000). Low threshold fibres are considered to be mainly involved in control of micturition, while high threshold afferents (threshold > 20 mmHg) have been associated with the generation of painful sensations (de Groat, 1997). In several studies in vivo, low threshold stretch-sensitive afferents were reported to fire in proportion to intravesical pressure, behaving as ‘in-series tension receptors’ (Iggo, 1955; Häbler et al. 1993; Shea et al. 2000). However, it has been postulated that there may also be ‘volume’ receptors, which sense bladder distension irrespective of pressure (Kuru, 1965; Morrison, 1999). In other reports, one class of mechanoreceptor had firing rates linearly related to tension, while others had a plateau or even decreased firing rates at higher pressure (Iggo, 1955; Downie & Armour, 1992; Shea et al. 2000). This response pattern was interpreted as representing ‘volume receptors’ (Shea et al. 2000). The piecemeal nature of the available data means that it is still unclear exactly how many functional classes of distension-sensitive afferents innervate the bladder.

Thus there is a need for a comprehensive characterization of bladder mechanoreceptors in terms of their adequate mechanical stimuli, chemosensitivity, location of their receptive field and electrophysiological parameters. The aim of this study was to distinguish the different functional classes of extrinsic sensory neurons innervating the bladder in vitro where highly controlled mechanical and chemical stimulation could be applied and the exact location of receptive fields could be determined.

Preliminary data were presented at the International Society for Autonomic Neuroscience (ISAN) meeting in Marseilles and subsequently published as a conference paper (Zagorodnyuk et al. 2006).

Methods

Extracellular recording

Adult male guinea pigs (N = 66 guinea pigs), weighing between 200 and 350 g, were killed by a blow to the occipital region and exsanguinated, in a manner approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of Flinders University. The bladder was removed and opened into a flat sheet and washed with Krebs solution (mm: NaCl, 118; KCl, 4.75; NaH2PO4, 1.0; NaHCO3, 25; MgCl2, 1.2; CaCl2, 2.5; glucose, 11; bubbled with 95% O2 – 5% CO2). Full thickness, small (12 mm × 15–20 mm) flat sheet preparations were studied with the mucosa uppermost. ‘Close-to-target’ extracellular recordings (Zagorodnyuk & Brookes, 2000; Zagorodnyuk et al. 2006) were made from axons in fine nerve trunks (98 nerve trunks from 66 guinea pigs) entering the bladder trigone. The preparations were pinned down along one edge in a 5 ml organ bath while the other edge was attached to a ‘tissue stretcher’ (a microprocessor-controlled stepper motor) with in-series built isometric force transducer, DSC no. 46-1001-01 (Kistler-Morse, Redmond, WA, USA) (Brookes et al. 1999; Zagorodnyuk & Brookes, 2000; Zagorodnyuk et al. 2006). The slack was taken up to give a resting tension of ∼1 mN and at least 60 min of equilibration was allowed before experiments started. The preparations were stretched at 1 mm s−1 for distances of 1–4 mm and held for 10 s, at 3–4 min intervals. Mean firing rate of afferent units was calculated during 10 s stretches. Stretch-evoked increases in tension were calculated as integrated tension (area under the curve) in units of newton seconds.

To distinguish the major classes of bladder mechanoreceptors, the following strategy was developed. First, the preparation was stretched by 1–4 mm and stretch-sensitive single units (if any) were identified. Then, the mucosa was stroked with light von Frey hairs (0.05–1 mN) to determine receptive field of mucosal mechano-sensitive units (the receptive field was then marked with carbon particles; Zagorodnyuk & Brookes, 2000). For afferents insensitive to mucosal stroking, the sizes of focal mechanoreceptive fields within the thickness of the wall (‘hotspots’) were located by compressing the tissue (from the mucosal surface) with calibrated (0.5–2 mN) von Frey hairs. ‘Hotspots’ identified in this way were marked with carbon particles on the von Frey hair. Stimulus–response curves for focal compression (maximum response from 2 to 3 attempts) or stroking were constructed; 5 consecutive strokes (with 2–3 s intervals) were applied with each von Frey hair and the three largest responses were averaged. One class of mucosal units showed bursting activity in response to stroking (lasting up to 2 s); for these units two to three strokes were applied, and average firing was quantified. Since stroking with stiff von Frey hairs (> 2 mN) usually evoked muscle contractions, all stimulus–response studies using probing or stroking with von Frey hairs were carried out in the presence of nicardipine (3 μm) to minimize such mechanical interference. Despite this, stroking with stiff von Frey hairs (5–10 mN) sometimes still evoked small contractions of smooth muscle even in the presence of nicardipine. Stroking with lighter von Frey hairs (0.05–0.1 mN) selectively activated the urothelium and the lamina propria, since contractile responses were not recorded either visually or by the isometric transducer. Chemical stimuli (1 mm α,β-methylene ATP, hypertonic solutions (500 mm NaCl and 1 m mannitol in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)) and 3 μm capsaicin) were applied either by addition into a small chamber, which was sealed with silicone grease above a marked hotspot area, or by direct application from a pipette onto the marked receptive field. In preliminary experiments, the effects of hypertonic solution (500 mm NaCl) and α,β-methylene ATP were studied in Krebs solution either with or without nicardipine (3 μm). No differences were observed and the data were pooled. However, we cannot exclude that nicardipine subtly modified responses, although the major chemosensitivity reported by other groups was obviously preserved. In most cases, α,β-methylene ATP responses showed fast desensitization. To compare the effects of α,β-methylene ATP, hypertonic solution and capsaicin, the firing rate of afferent units was averaged for a 5 s period around the peak response.

Fine nerve fibres (originating from the pelvic ganglia) were dissected free and, together with a separate strand of connective tissue, were pulled into a second small chamber (∼1 ml volume) separated by a coverslip and Silicone grease barrier (Ajax Chemicals, Australia). The small chamber was filled with paraffin oil and differential extracellular recordings were made via platinum electrodes. Signals were amplified (DAM 80, WPI, USA) and recorded at 20 kHz with a MacLab 8sp (ADInstruments, Sydney, Australia) attached to an Apple iMac G5 computer using Chart 5.4.2 software (ADInstruments). Single units were discriminated by amplitude and duration using Spike Histogram software (ADInstruments).

Drugs

α,β-Methylene ATP, capsaicin and mannitol were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MI, USA).

Data analysis

Results are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean, with n referring to the number of units and N to the number of animals. Statistical analysis was performed by Student's two-tailed t test for paired or unpaired data or by repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA, one-way or two-way) using Prism v.4 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Additional univariate and multivariate ANOVAS were done using SPSS v.13 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Differences were considered significant if P < 0.05. To see whether sensory neurons could be classified on the basis of their responses to stretch and stroke and electrophysiological properties, a series of discriminant analyses (Norusis, 1993; Tabachnik & Fidell, 1996) were carried out with SPSS v.13.

Results

Four distinct classes of afferents could be distinguished using a range of mechanical stimuli (1–4 mm stretch and light von Frey hair stroking of receptive fields) and chemical stimuli (1 mm α,β-methylene ATP, hypertonic solutions (500 mm NaCl and 1 m mannitol) and 3 μm capsaicin). These were two types of low threshold distension-sensitive afferents – muscle mechanoreceptors and muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors; and two types of distension-insensitive afferents – mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors and mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors.

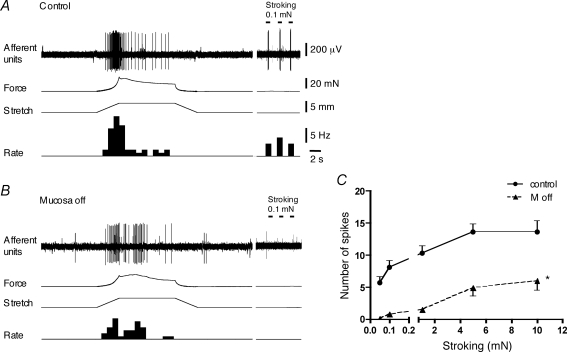

Distension-sensitive afferents: muscle mechanoreceptors

Distension-sensitive muscle mechanoreceptors were silent in bladder preparations in vitro in Krebs solution without (n = 7) or with 3 μm nicardipine (n = 9) and had low thresholds (∼1–2 mm, under 1 mN preload) to stretch applied in the direction of the bladder dome to neck (n = 16, N = 16). Following the onset of rapid stretch (1–4 mm at 1 mm s−1), muscle mechanoreceptor showed an initial burst of firing, followed by slow adaptation, which paralleled muscle tension in time course (Fig. 1). These afferents could be activated by compression of their receptive fields with von Frey hairs (0.5–1 mN). In the presence of nicardipine (3 μm), typically a 0.5 mN probe evoked 6.7 ± 2.0 spikes (n = 6, N = 6) (Fig. 1) but a 0.1 mN von Frey hair had no effect in any units (n = 6). Their receptive fields consisted of one to nine discrete hotspots (mean 4 ± 1, n = 8, N = 8) within the average area of 2.5 ± 0.6 mm2 (n = 8, N = 8). Stroking across their receptive fields with light von Frey hairs (0.05–0.1 mN) did not activate these afferents and did not evoke muscle contractions (n = 9, N = 9). Stroking with 1 mN von Frey hairs evoked firing in 4 out 7 preparations but in each case only a single spike occurred (Fig. 2). When stroking was attempted with stiffer von Frey hairs (5–10 mN), small muscle contractions were generated even in the presence of nicardipine (3 μm) in 4 out of 6 preparations; in some cases the contractions were associated with firing of the neurons.

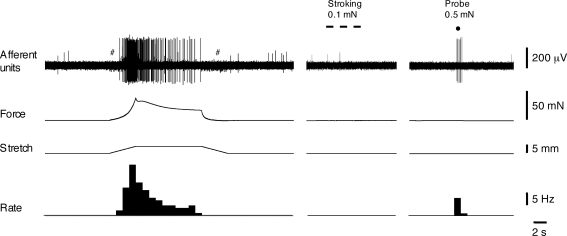

Figure 1.

Low threshold, distension-sensitive muscle mechanoreceptors in the bladder Responses of muscle mechanoreceptors to fast 5 mm stretch (at 1 mm s−1, held for 10 s) and to 0.5 mN von Frey hair compressing of the receptive field (indicated by dot). Note that stroking of the receptive field with a 0.1 mN von Frey hair (3 strokes, indicated by bars) did not activate this afferent. # shows stepper motor artefacts.

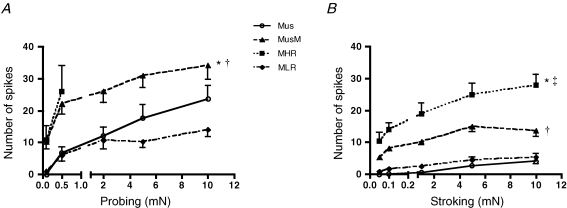

Figure 2.

Mechanosensitivity of four classes of bladder mechanoreceptors A, stimulus–response function of muscle (Mus, n = 6, N = 6), muscle-mucosal (MusM, n = 8, N = 8)), mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors (MHR, n = 5, N = 5 responses only to 0.1 and 0.5 mN probing) and mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors (MLR, n = 9, N = 9) to graded probing of their receptive fields with von Frey hairs. Note that responses to probing of muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors were significantly larger than those for muscle and mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors, respectively (*P < 0.01 and †P < 0.001, 2-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post hoc tests). B, stimulus–response function of muscle mechanoreceptors (Mus, n = 6, N = 6), muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors (MusM, n = 10, N = 10), mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors (MHR, n = 7, N = 7) and mucosal low-responding (MLR) mechanoreceptors (n = 9, N = 9) to graded stroking of their receptive fields with von Frey hairs. Note that responses to stroking of mucosal high-responding and muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors were significantly larger than muscle and mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors (* and †P < 0.001, 2-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post hoc tests). There were also significant differences in responses to stroking, between mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors and muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors (‡P < 0.001). Note that nicardipine (3 μm) was present throughout all experiments with probing and stroking of receptive fields with von Frey hairs.

Removal of the superficial mucosal layer (urothelium) during the recording period did not affect stretch-induced firing (n = 4, N = 4) and contractile responses (N = 4) (Fig. 3A and B), nor did it evoke firing during the actual dissection procedure (Krebs solution without nicardipine). In five additional preparations, the urothelium was removed together with the lamina propria. In these cases, stretch-induced firing was slightly reduced (n = 5, N = 5, P < 0.005) (Fig. 3C), in parallel to reduced muscle responses to stretch (measured as area under the force–time curve, N = 5, P < 0.0001, Fig. 3D). When baseline tone was re-adjusted to the control value after this dissection, stretch-evoked contractile responses recovered to control levels as did distension-induced firing (n = 5, N = 5, Fig. 3C and D). The data suggest that receptive fields of muscle mechanoreceptors are probably located in the muscle layers with minimal involvement of the lamina propria or urothelium.

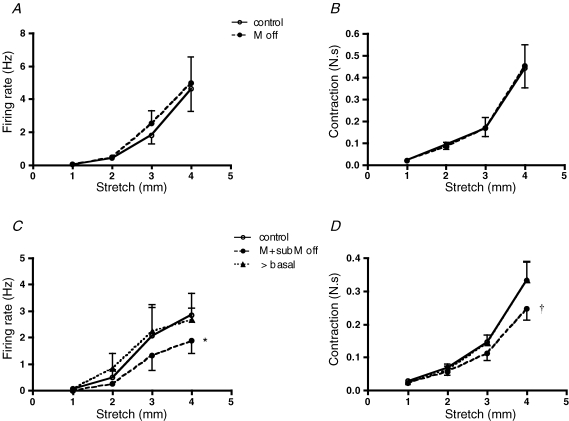

Figure 3.

The effect of removing the urothelium with or without lamina propria on stretch-induced firing of muscle mechanoreceptors A and B, lack of the effects of removal of urothelium on stretch-induced firing (n = 4, N = 4) and muscle contractile responses (N = 4). C and D, removal of the urothelium together with lamina propria reduced but did not abolish stretch-induced firing (n = 5, N = 5, *P < 0.005) and contractile responses (N = 5, †P < 0.0001, 2-way ANOVA). Note that when baseline tone was re-adjusted to control values, stretch-evoked muscle responses and firing recovered to control levels.

In most cases, chemical stimuli applied to the mucosa overlying receptive fields did not activate muscle mechanoreceptors. These afferents were not sensitive to application of hypertonic solution of NaCl (500 mm, n = 8, N = 8) or to capsaicin (3 μm, n = 7, N = 7) applied locally in the presence of 3 μm nicardipine. Applying α,β-methylene ATP (1 mm) to the mucosal surface of the receptive field did not activate these afferents in most cases (n = 5, N = 5 from n = 7, N = 7). In some experiments, the superficial mucosa overlying the area of the hotspots was removed. After removal of the urothelium, capsaicin (3 μm, n = 2) or α,β-methylene ATP (1 mm, n = 2) applied onto lamina propria overlying receptive fields did not activate muscle mechanoreceptors, although responses to probing with von Frey hairs and to stretch were preserved.

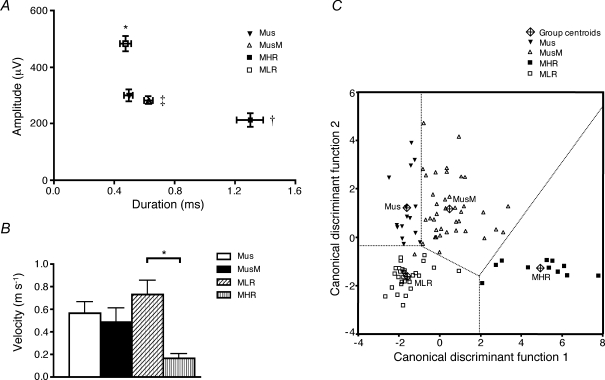

Low threshold distension-sensitive muscle mechanoreceptors had an average spike amplitude of 299 ± 21 μV (n = 16, N = 16) and spike duration (at half peak amplitude) of 0.49 ± 0.03 ms (n = 16, N = 16). Their conduction velocity was 0.56 ± 0.10 m s−1 (n = 4, N = 4), corresponding to the C fibre range (Fig. 10).

Figure 10.

Electrophysiological parameters and plot of the canonical discriminant functions used to classify sensory neurons on the bases of their spike duration and amplitude, and responses to 4 mm stretch and to 0.1 mN von Frey hair stroking A, the amplitude of spikes of mucosal low-responding (MLR) mechanoreceptors was significantly larger (n = 30, N = 29, *P < 0.0001, univariate ANOVA, Ryan–Einot–Gabriel–Welsch post hoc tests) than that of all other classes. Duration of mucosal high-responding (MHR) mechanoreceptors (n = 13, N = 12) was significantly (†P < 0.0001) longer than that of all other others; duration of muscle-mucosal (MusM) mechanoreceptors (n = 42, N = 40) was significantly (‡P < 0.0001) longer than that of mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors (n = 30, N = 29). B, conduction velocity of mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors (n = 7, N = 7) was significantly (*P < 0.05, univariate ANOVA, Ryan–Einot–Gabriel–Welsch post hoc tests) faster than that of mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors (n = 4, N = 4). C, plot (‘territorial map’) of the canonical discriminant functions used to classify sensory neurons based on four parameters: spike duration and amplitude, and responses to 4 mm stretch and light (0.1 mN) von Frey hair stroking. The value for each neuron was calculated according to the two canonical discriminant functions F1 and F2. Canonical discriminant function coefficients were for function 1: F1 = (0.253 × stroke) + (3.20 × duration) − (0.002 × amplitude) − 2.646; and for function 2: F2 = (−0.013 × stroke) − (0.446 × duration) − (0.003 × amplitude) + (0.047 × stretch) + 0.225, respectively. The group centroids are the values of the discriminant functions calculated for the means of these four variables in each class of bladder sensory neurons.

During the course of the study, an additional three mechanosensitive units with high thresholds to stretch (3–4 mm, N = 3) were encountered. These units were not sensitive to stroking of their receptive fields with light von Frey hairs (0.05–0.1 mN) and were not further investigated due to their scarcity.

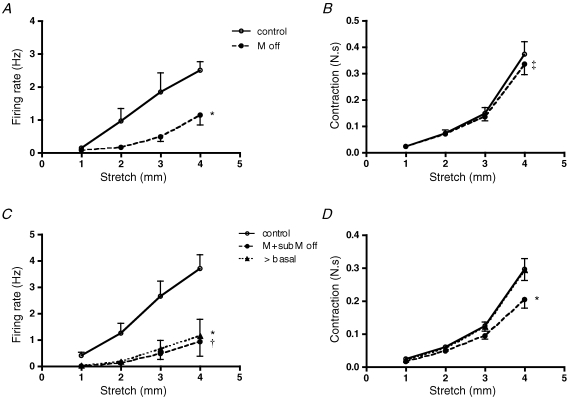

Distension-sensitive afferents: muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors

A second class of distension-sensitive bladder afferents, muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors, could be activated both by distension (1–4 mm) and by stroking the overlying mucosa with light von Frey hairs (0.05–0.1 mN, n = 42, N = 40, see Fig. 4). The distension threshold for activation of these receptors (1–2 mm) was similar to that of muscle mechanoreceptors. These mechanoreceptors in most cases were silent at rest in Krebs solution both with (n = 16) and without (n = 18) 3 μm nicardipine. Only two units had irregular spontaneous activity (0.21–0.27 imp s−1) recorded in the presence of nicardipine. However, in preparations which were not treated with nicardipine, six units showed occasional bursting activity associated with spontaneous muscle contractions (at intervals of 20–65 s). Such spontaneous contractile activity was not seen in the presence of nicardipine (3 μm). In the presence of nicardipine (3 μm), stroking the mucosa with 0.1 and 1 mN von Frey hairs evoked 8.1 ± 0.8 and 10.2 ± 1.0 spikes (n = 10, N = 9), respectively (Fig. 2). The duration of responses to 0.1 and 1 mN strokes was 0.17 ± 0.02 s and 0.22 ± 0.03 s (n = 10, N = 9), respectively. Importantly, stroking mucosa with light (0.05–1 mN) von Frey hairs did not evoke any contractile responses, in the presence of nicardipine (3 μm). These units were more sensitive than muscle mechanoreceptors to compression of their receptive fields with light von Frey hairs: the number of generated spikes in response to 0.1 mN and 0.5 mN von Frey hairs were 10 ± 2.2 and 22 ± 3.2 (n = 8, N = 7), respectively (Fig. 2). The receptive fields of these afferent fibres were concentrated in the trigone region of the guinea pig bladder and consisted of discrete small sensitive areas (0.5–1 mm2). In most cases one to four sensitive areas (mean 1.9 ± 0.2, n = 34, N = 32) were detected by light stroking of the mucosa, with average total area of 2.9 ± 0.5 mm2 (n = 16, N = 16).

Figure 4.

Typical responses of low threshold, distension-sensitive muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors to stretch and mucosal stroking before and after removal of the urothelium and the lamina propria A, responses of low threshold muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors to fast 4 mm stretch (at 1 mm s−1, held for 10 s) and to a 0.1 mN von Frey hair stroking of the receptive field (three strokes, indicated by bars). B, removal of both the urothelium and the lamina propria reduced stretch-induced firing. After removal the urothelium and the lamina propria, baseline tone was re-adjusted to control values. A and B, no nicardipine in Krebs solution. C, removal of the urothelium reduced stroking-induced firing of muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors (n = 8, N = 8, *P < 0.0001, 2-way ANOVA, 3 μm nicardipine in Krebs solution).

In the presence of nicardipine (3 μm), removal of the urothelium significantly reduced firing evoked by light stroking (n = 8, N = 8, P < 0.0005) (Fig. 4C). Responses to 1 mN stroking were reduced after the urothelium was removed by 83 ± 5% (n = 8, N = 8). Removal of the urothelium also reduced firing evoked by stretch (Figs 4A and B and 5A, n = 10, N = 10, P < 0.001, Krebs solution without nicardipine). Note that contractile responses were not reduced from 1 to 3 mm; with a 4 mm stretch, contraction was slightly but significantly reduced (N = 10, P < 0.01) (Fig. 5B). When both the urothelium and the lamina propria were removed there was a significant reduction of both stretch-induced firing (n = 9, N = 9, P < 0.0001) and contractile responses (N = 9, P < 0.0001). In 5 out of 9 units, stretch-induced firing was completely abolished indicating that this procedure removed mechanotransduction sites of the muscle-mucosal afferents. After baseline tone was re-adjusted to control values, stretch-evoked contractile responses recovered to control values, but stretch-induced firing remained significantly suppressed (n = 9, N = 9, P < 0.001) (Fig. 5C and D). These observations suggest that muscle-mucosal afferents may have receptive fields in both the outer smooth muscle and lamina propria (in the vicinity of the urothelium).

Figure 5.

The effect of removal the urothelium with or without lamina propria on stretch-induced firing of muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors A and B, the removal of the urothelium significantly reduced stretch-induced firing (n = 10, N = 10, *P < 0.0005) but contractile responses were only slightly reduced to 4 mm stretch (N = 10, ‡P < 0.01, 2-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post hoc tests). C and D, removing the urothelium together with lamina propria significantly reduced both stretch-induced firing (n = 9, N = 9, *P < 0.0001) and contractile responses (N = 9, *P < 0.0001). Note that after baseline tone was re-adjusted to control values, stretch-evoked contractile responses recovered to control levels but stretch-induced firing remained significantly reduced (†P < 0.001, 2-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post hoc tests).

Most muscle-mucosal afferents could be activated by hypertonic stimuli: 500 mm NaCl (n = 25, N = 23 out of n = 27, N = 25) or 1 m mannitol (n = 4, N = 4) applied locally to their receptive fields in the mucosa (Fig. 6). When hypertonic NaCl (500 mm) was added into a chamber sealed over their marked receptive fields, it evoked mean firing of 14.7 ± 2.1 Hz (n = 12, N = 12). The latency of the response was 7.6 ± 2.1 s (n = 12, N = 12) and firing continued as long as the hypertonic solution was kept in the well (1 min). Most of muscle-mucosal afferents were also activated by mucosal application of α,β-methylene ATP (1 mm, n = 15, N = 15 out of n = 17, N = 17) (Fig. 6), but this purinergic agonist only evoked detectable contractions of the smooth muscle in 1 of 17 preparations. When α,β-methylene ATP was applied via the chamber, it evoked mean firing of 8.3 ± 0.9 Hz (n = 6, N = 6); its effect was short-lasting (5.6 ± 1.3 s, n = 6, N = 6) and had a short latency (0.9 ± 0.3 s, n = 6, N = 6). Both duration and latency of responses to α,β-methylene ATP were significantly shorter than those to hypertonic stimuli (P < 0.05 unpaired t test). Muscle-mucosal afferents were not sensitive to capsaicin (3 μm, n = 13, N = 13) applied to the mucosa overlying their receptive fields. In six cases, capsaicin (3 μm) was applied again after removal of the urothelium but in no cases evoked firing (n = 6, N = 6).

Figure 6.

The effect of application of α,β-methylene ATP and hypertonic NaCl on muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors Muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptor was activated by both stretch and stroking its receptive field with a 0.1 mN von Frey hair. Spritzing both 1 mm α,β-methylene ATP and 500 mm NaCl on the mucosa activated this mechanoreceptor. Note that the latency and duration of the α,β-methylene ATP-induced response were significantly shorter than those for hypertonic NaCl. Note that nicardipine (3 μm) was present throughout the experiment.

The electrophysiological parameters of muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors were not significantly different from those of muscle mechanoreceptors (Fig. 10). They had a mean spike amplitude of 284 ± 14 μV (n = 42, N = 40), duration (at half peak amplitude) of 0.63 ± 0.03 ms (n = 42, N = 40) and conduction velocity of 0.49 ± 0.12 m s−1 (n = 7, N = 6).

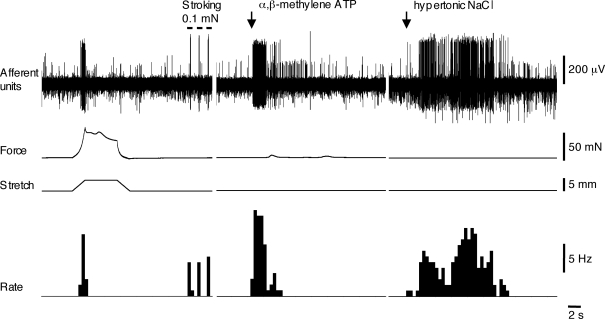

Distension-insensitive afferents: mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors

The third class of bladder afferents, mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors, were not sensitive to stretch (1–5 mm) but responded vigorously to mucosal stroking with light von Frey hairs (0.05–0.1 mN, n = 13, N = 12). In most cases, mucosal high responding mechanoreceptors were spontaneously active, firing at 0.61 ± 0.12 Hz (n = 12, N = 11, 2 of 3 units without nicardipine and 10 of 10 units in 3 μm nicardipine). These units generated more spikes to mucosal stroking than the muscle-mucosal units previously described (P < 0.01, see Fig. 2B). In the presence of nicardipine (3 μm), the number of spikes evoked by 0.1 and 1 mN stroking were 14.0 ± 2.1 (n = 7, N = 6) and 18.9 ± 3.4 (n = 7, N = 6), respectively, while durations of the responses were 1.29 ± 0.19 s (n = 7, N = 6) and 2.07 ± 0.48 s (n = 7, N = 6), respectively (Figs 2 and 7). Mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors usually had a small receptive field containing 2 ± 0.5 hotspots (range: 1–6 hotspots, n = 11, N = 10) within an area of 2.0 ± 0.7 mm2 (n = 11, N = 10). These units were also very sensitive to probing with light von Frey hairs (0.1–1 mN), generating 10.8 ± 4.4 s (n = 4, N = 4) and 26.0 ± 8.0 (n = 5, N = 4) spikes in response to 0.1 and 0.5 mN probing, respectively (Fig. 2A). Probing with stiffer von Frey hairs often evoked irreversible damage to these units (responses to subsequent strokes with light von Frey hairs were diminished or abolished).

Figure 7.

Mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors in the bladder A, responses of low threshold muscle mechanoreceptors (Mus) to fast 5 mm stretch (at 1 mm s−1, held for 10 s) and activation of mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptor (MHR) unit by 0.1 mN and 1 mN stroking of the receptive field (continuous recordings from the same nerve trunk). # indicates stepper motor artefacts. B and C, removal of the urothelium significantly reduced stroking-induced firing of MHR mechanoreceptors. For C, n = 4, N = 4, *P < 0.0001, 2-way ANOVA. D, the shape of superimposed seven action potentials for a muscle mechanoreceptor and mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptor unit. Note that nicardipine (3 μm) was present throughout all experiments in A, B and C.

When the urothelial layer was removed, responses of mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors to stroking were greatly reduced (n = 4, N = 4, P < 0.0001, Fig. 7). Responses to 1 mN stroking were reduced after urothelial removal by 84 ± 7% (n = 4, N = 4). This suggests that they are touch-sensitive mucosal mechanoreceptors with endings in the lamina propria in the vicinity of the urothelium. Supporting this, there was a marked increase in spontaneous firing frequency during the process of removing the urothelium in many units of this type.

Mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors could be activated by hypertonic saline (NaCl 500 mm), α,β-methylene ATP (1 mm) and by capsaicin (3 μm) applied locally (spritzed) to their receptive fields in the mucosa in the presence of nicardipine (3 μm). When hypertonic NaCl (500 mm) was spritzed over their receptive fields, it evoked a mean firing rate of 9.3 ± 1.6 Hz (n = 5, N = 5), with a latency of 7.0 ± 2.5 s (n = 5, N = 5). α,β-Methylene ATP (1 mm) evoked 7.3 ± 1.2 Hz (n = 6, N = 5) mean firing rate with a latency of 2.1 ± 0.4 s (n = 6, N = 5) and capsaicin evoked 11.3 ± 1.8 Hz (n = 8, N = 7) mean firing rate with a latency of 5.3 ± 1.3 s (n = 8, N = 7). In three preparations, the same unit was activated by hypertonic NaCl, α,β-methylene ATP and capsaicin. One mucosal high-responding unit was insensitive to 3 μm capsaicin. Electrophysiologically, these units had the lowest spike amplitude of all classes recorded (215 ± 24 μV, n = 13, N = 12) and the longest spike duration (1.30 ± 0.09 ms, n = 13, N = 12) and slowest conduction velocity (0.16 ± 0.04 m s−1, n = 4, N = 4) (Fig. 10).

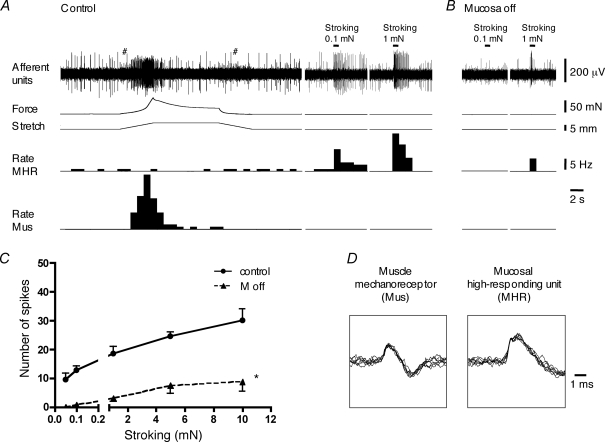

Distension-insensitive afferents: mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors

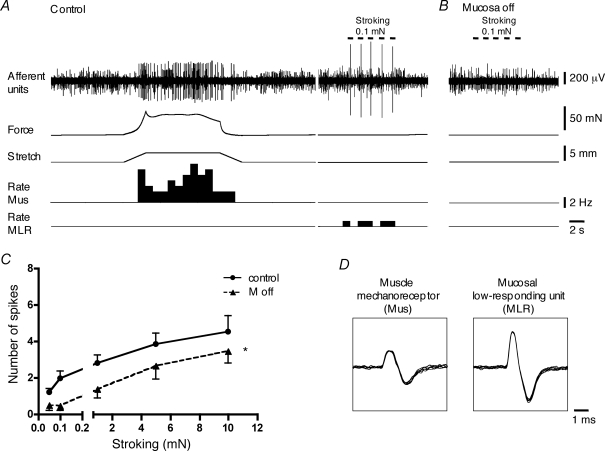

The fourth class of bladder afferents, mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors, were not distension sensitive (1–5 mm) but could be weakly activated by light von Frey hair stroking of their receptive field (n = 30, N = 29) (Fig. 8). These mechanoreceptors were silent in Krebs solution with (n = 16) or without (n = 14) 3 μm nicardipine. In the presence of nicardipine (3 μm), the number of spikes evoked by 0.1 and 1 mN stroking was 1.7 ± 0.12 and 2.5 ± 0.3 (n = 9, N = 9), respectively. Responses to stroking ceased immediately on cessation of the stimulus, unlike mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors (Fig. 9). The duration of the responses to 0.1 and 1 mN stroking was 0.05 ± 0.01 s (n = 3, N = 3; in another 6 units stroking only evoked a single spike) and 0.06 ± 0.01 s (n = 8, N = 8), respectively. These units were also were less sensitive to von Frey probing of their receptive fields in the mucosa, compared to the muscle-mucosal receptors and mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors. In response to 0.1 and 0.5 mN von Frey hair probing they generated 0.9 ± 0.4 and 6.0 ± 1.8 (n = 9, N = 9) spikes, respectively (Fig. 2). In contrast to other classes of bladder afferents with mucosal sensitivity, low-responding mechanoreceptors had large receptive fields with one to four hotspots (2.0 ± 0.2, n = 24, N = 23) spread over an area of 10.9 ± 2.5 mm2 (n = 9, N = 9). Removal of the urothelium reduced (n = 8, N = 8, P < 0.0001) their sensitivity to mucosal stroking (Fig. 8). Responses to 1 mN stroking were reduced after urothelial removal by 50 ± 19% (n = 8, N = 8). This suggest that mechanosensitive endings of these mechanoreceptors are somewhere in the lamina propria, close to the urothelium as suggested for both muscle-mucosal and mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors.

Figure 8.

Mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors in the bladder A, responses of low threshold muscle mechanoreceptors (Mus) to fast 5 mm stretch (at 1 mm s−1, held for 10 s) and activation of mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors (MLR) by 0.1 mN stroking of the receptive field (continuous recordings from the same nerve trunk). B and C, removal of the urothelium significantly reduced stroking-induced firing. For C, n = 8, N = 8, *P < 0.0001, 2-way ANOVA. D, the shape of superimposed seven action potentials for muscle mechanoreceptors and mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors. Note that nicardipine (3 μm) was present throughout all experiments in A, B and C.

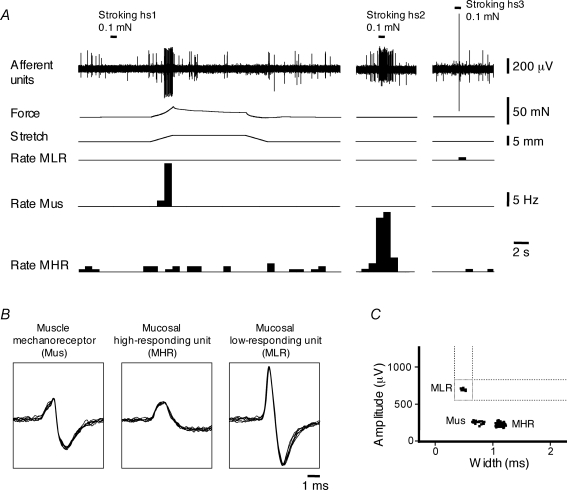

Figure 9.

Discrimination of three units from three different classes of sensory neurons recorded in a single nerve trunk A, muscle mechanoreceptor unit (Mus) is activated by fast 3 mm stretch (at 1 mm s−1, held for 10 s) but not by 0.1 mN mucosal stroking of their receptive field (hotspot (hs) 1). Activation of mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptor unit (MHR) and mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptor (MLR) unit by 0.1 mN stroking of their receptive field (hs2 and hs3, respectively) but not by stretch. B, shape of superimposed seven action potentials for muscle mechanoreceptor and mucosal high-responding and mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors. C, discriminator window for recordings from a single nerve trunk presented in A shows three clusters of units (Mus, MHR and MLR) discriminated by spike amplitude and duration. Note that nicardipine (3 μm) was present throughout all experiments in A.

This class of afferents could not be activated by α,β-methylene ATP (1 mm, n = 10, N = 10) or capsaicin (3 μm, n = 11, N = 11) applied to the mucosal surface overlying their receptive fields. Hypertonic (500 mm) NaCl evoked firing in only 2 out of 13 units. After removal of the urothelium these units were still insensitive to 1 mm α,β-methylene ATP (n = 3, N = 3) or to 3 μm capsaicin (n = 3, N = 3). Electrophysiologically, mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors had the largest spike amplitude (484 ± 26 μV, n = 30, N = 29) and shortest spike duration (0.47 ± 0.04 ms, n = 30, N = 29) of all classes characterized (Fig. 10). They were also amongst the fastest conducting afferents (0.73 ± 0.12 m s−1, n = 7, N = 7).

Multivariate statistical analysis

The experimental data indicated that there were significant differences in electrophysiological parameters (spike amplitude, duration and conduction velocity), responses to mechanical stimuli (stretch and stroking) and chemical stimuli between the different afferent units recorded. Our initial grouping into four classes was based only on responses to stretch and to light (0.1 mN) von Frey hair stroking. Subsequently, it became apparent that electrophysiological parameters including spike duration and spike amplitude covaried with other characteristics in the four classes of sensory neurons (Fig. 9). To test whether our preliminary classification scheme could be objectively validated, we carried out a series of multivariate statistical analyses.

Multiple correlation analysis was used to determine whether there were significant correlations between any of the four main parameters (spike duration, spike amplitude, response to 4 mm stretch and mucosal stroking with 0.1 mN von Frey hairs) in 95 fully characterized afferent units. A significant positive correlation between spike duration and responses to stroke was seen (r = 0.66, P < 0.01, Pearson correlation, 2-tailed). Significant inverse correlations were identified between three pairs of parameters: spike amplitude and responses to stroke (r = −0.38, P < 0.01), spike duration and responses to stretch (r = −0.34, P < 0.01) and spike duration and spike amplitude (r = −0.37, P < 0.01).

Univariate ANOVA was used to determine how each of the four parameters differed between the four proposed classes of afferents. In this analysis, we have included several additional parameters, including conduction velocity and responses to capsaicin, hypertonic NaCl and α,β-methylene ATP. Using Ryan–Einot–Gabriel–Welsch post hoc tests, spike amplitude of mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors was significantly larger than in other classes (for overall comparison, F3,97 = 28, P < 0.0001). Spike duration of mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors was significantly longer than that of all other classes and spike duration of muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors was longer than spike duration of mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors (F3,97 = 58, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 10A). Responses to stretch (4 mm) of muscle-mucosal and muscle mechanoreceptors were similar, but both were significantly larger than stretch responses of mucosal high-responding and mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors (F3,94 = 54, P < 0.0001). Responses of mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors to light (0.1 mN) von Frey hair stroking were significantly larger that those for muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors; the latter were larger than mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors and muscle mechanoreceptors (F3,94 = 78, P < 0.0001). The conduction velocity of mucosal low-responding units was significantly faster than mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptor units (F3,18 = 3.5, P < 0.05) (Fig. 10B). Only mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors responded to capsaicin, indicating that this substance can distinguish this class of afferents from others (F3,35 = 35, P < 0.0001). Responses to hypertonic NaCl were similar for muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors and mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors and they were significantly larger than those for mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors and muscle mechanoreceptors (F3,47 = 11, P < 0.0001). Responses to α,β-methylene ATP were similar for muscle-mucosal and mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors and were significantly larger than those of muscle mechanoreceptors and mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors (F3,34 = 18, P < 0.0001).

Multivariate ANOVA produced similar results, which confirmed that electrophysiological characteristics (spike amplitude and duration) varied significantly between the neuronal classes in addition to responses to mechanical and chemical stimuli. However, the ANOVAs presuppose a classification of the neuronal types using some of the same properties. To eliminate this potential source of bias, we carried out a discriminant analysis (Norusis, 1993; Tabachnik & Fidell, 1996) on a set of 95 neurons. The analysis converged on two canonical discriminant functions that explained 98% of the total variance. The first canonical discriminant function (F1) explained 68% of the variance and separated mucosal high-responding and mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors from muscle and muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors, on the basis of their responses to stroke and their spike duration (Fig. 10C). The second canonical discriminant function (F2) explained 30% of the variance and separated classes on the basis of their responses to stretch. As shown in Fig. 10C mucosal high-responding (MHR) mechanoreceptors were discriminated when F1 > 2 and F2 < 0; mucosal low-responding (MLR) mechanoreceptors when F1 < 2 and F2 < 0; muscle (Mus) mechanoreceptors when F1 < −1 and F2 > 0; and muscle-mucosal (MusM) mechanoreceptors when F1 > −1 and F2 > 0. The analysis classified 94.7% of neurons according to our original classifications (compared with a calculated 39% correct classification by chance). More important, using a jack-knife-based cross-validation, 89.5% of cross-validated cases were correctly classified (see Norusis, 1993; Tabachnik & Fidell, 1996). Thus, these analyses show that spike characteristics (duration and amplitude) and responses to stretch and light stroke can be used to classify about 90% of bladder afferents into four functionally distinct classes.

High threshold mechanoreceptors

During the course of the study, we recorded a small number of units (n = 5, N = 3) which were insensitive to light (0.05–1 mN) mucosal stroking or to 1–5 mm distension. These high-threshold stretch-insensitive units could be activated by 3 μm capsaicin (n = 3, N = 2 out of n = 5, N = 3) or by compressing their receptive fields with stiff von Frey hairs (2–10 mN, n = 5, N = 3). However they were susceptible to damage (responses declined with repeated probing) and were too scarce to be further investigated or included in statistical analysis.

Discussion

The main finding of this study is that four distinct classes of mechanosensory afferents can be distinguished in the bladder in vitro, providing a more complete account of the sensory innervation of the bladder than previous in vivo studies. These classes of neurons we revealed by systematically recording responses to a range of mechanical and chemical stimuli, identifying the location of transduction sites by microdissection and measuring electrophysiological parameters. Although previous studies have distinguished distension-sensitive and distension-insensitive afferents, this study has shown that they could be subdividided into muscle mechanoreceptors, muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors, mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors and mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors.

Distension-sensitive afferents: muscle mechanoreceptors

The first class of sensory fibres, muscle mechanoreceptors, accounted for 15% of bladder afferents recorded. They were powerfully activated by stretch but not by mucosal stroking with light (0.05–1 mN) von Frey hairs. In most cases they were not affected by hypertonic saline, α,β-methylene ATP or capsaicin applied to the mucosa. Removal of the urothelium and lamina propria did not affect their distension-induced firing. These observatoins suggest that these low threshold, distension-sensitive muscle mechanoreceptors have mechanotransduction sites restricted to the outer layers of smooth muscle. Muscle mechanoreceptors probably correspond to ‘in-series’ tension receptors previously described in vivo (Iggo, 1955; Häbler et al. 1993; Shea et al. 2000). They are likely to act primarily as ‘tension receptors’, activated by both distension and by contraction of the bladder evoked by excitatory transmitters, ATP and acetylcholine (Zagorodnyuk et al. unpublished observations). They showed similar characteristics to the low threshold mechanoreceptors which innervate the guinea pig rectum, for which the adequate stimulus is mechanical distortion of mechano-sensitive endings located in myenteric ganglia, by simultaneous contraction of longitudinal and circular muscle (Lynn et al. 2005). Detailed studies will be necessary to determine exactly the adequate mechanical stimulus for muscle mechanoreceptors in the bladder.

As reported in studies of the whole bladder in vivo and in vitro (Iggo, 1955; Häbler et al. 1990; Sengupta & Gebhart, 1994; Shea et al. 2000; Rong et al. 2002) low threshold and high threshold stretch-sensitive afferents were identified. In a preliminary report we identified three high threshold units (Zagorodnyuk et al. 2006) and we identified three in the present study. Since they were relatively scarce, we were unable to investigate them in detail: more studies are necessary to further characterize high threshold stretch-sensitive mechanoreceptors.

Distension-sensitive afferents: muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors

The second class of sensory fibres, muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors, accounted for 39% of all afferents recorded in this study. They were activated by both stretch and mucosal stroking with light (0.05–1 mN) von Frey hairs and also were activated by hypertonic stimuli and by α,β-methylene ATP. Similar to muscle mechanoreceptors, muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors probably correspond to a subset of the low-threshold, ‘in-series’ tension receptors previously described in vivo (Iggo, 1955; Häbler et al. 1993; Shea et al. 2000). Our preliminary studies have shown that they can be activated by contractions evoked by distension or by excitatory transmitters, ATP and acetylcholine (Zagorodnyuk et al. 2006). Removal of the urothelium or lamina propria reduced significantly distension-induced firing of muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors, suggesting that they may have receptive fields in both the outer smooth muscle and lamina propria, close to the urothelium. The sensitivity of these afferents to mucosal applications of hypertonic stimuli or α,β-methylene ATP is consistent with having axonal endings close to the urothelium. It is likely that receptive fields close to the urothelium are more sensitive to mechanical stimuli than those in the outer muscle layer. When the suburothelial plexus is damaged by removal of urothelium, the remaining mechanosensitivity to both stretch and stroking was significantly reduced. In normal condition, the most sensitive receptive field (i.e. closest to the urothelium) drives the firing rate, resetting the excitability of less sensitive transduction sites in the muscle layer after each action potential. Similar interactions between multiple transduction sites have been experimentally demonstrated in vagal mechanoreceptors innervating the guinea-pig oesophagus (Zagorodnyuk & Brookes, 2000). The dual sites of mechanosensitivity of these afferents (muscle and mucosa) are comparable to the tension/mucosal afferents described in the vagal and pelvic pathways to the gut (Page & Blackshaw, 1998; Brierley et al. 2004).

These mechanoreceptors had low thresholds to stretch and were capsaicin insensitive, suggesting that they may be more involved in physiological control of bladder activity than in pain pathways. Their sensitivity to mucosal hypertonicity, which can modulate their excitability, is consistent with this suggestion. It is possible that this mucosal sensitivity is mediated by transmitters released from urothelial and/or other cells in the lamina propria, by distension or by mucosal chemical stimuli. ATP, acetylcholine, substance P, prostaglandins and nitric oxide (Burnstock, 2001; Birder, 2005) are among possible candidates for modulation of excitability of muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors. The mechanisms of mechanotransduction and activation of these afferents by hypertonic stimuli remain to be established.

The majority of muscle mechanoreceptors and muscle-mucosal afferents were silent in vitro (in either the presence or the absence of nicardipine). This is similar to pelvic afferents of the cat bladder recorded in vivo (Iggo, 1955; Häbler et al. 1990, 1993) and the mouse bladder in vitro (Rong et al. 2002), but contrasts with rat pelvic mechanoreceptors, most of which exhibited spontaneous firing in the absence of distension (Sengupta & Gebhart, 1994; Shea et al. 2000). However, in another study of the rat bladder in vivo, little or no basal activity of individual pelvic mechanoreceptors was recorded when the bladder was empty (Moss et al. 1997). Interestingly, when pelvic and lumbar (hypogastric) distension-sensitive afferents to the bladder and distal gut were compared in the same species (cats, rats and mice) most pelvic afferents were silent while > 40–50% of splanchnic (hypogastric) afferents were spontaneously active (Bahns et al. 1986, 1987; Moss et al. 1997; Brierley et al. 2004). It is worth mentioning that in the present study, recordings were probably made from both pelvic/sacral and hypogastric/lumbar afferent populations, since the recording site was distal to the pelvic ganglia (1–2 mm from the bladder). It has been reported that the majority of low threshold stretch-sensitive mechanoreceptors to the guinea pig rectum are also silent at rest in vitro (Lynn et al. 2003; Zagorodnyuk et al. 2005). Low threshold stretch-sensitive bladder afferents (muscle and muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors) comprised over 50% of all recorded afferents in the present study, similar to previous reports for the bladder or distal gut in vivo and in vitro (Sengupta & Gebhart, 1994; Wen & Morrison, 1995; Shea et al. 2000; Rong et al. 2002).

Distension-insensitive afferents: mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors

The third class of sensory fibres, mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors, accounted for 12% of all units recorded in this study. They were stretch-insensitive but could be activated by mucosal stroking with light (0.05–0.1 mN) von Frey hairs and by chemical stimuli. Stroking-induced firing was significantly reduced by removal of the urothelium. It is likely that mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors recorded in this study correspond to bladder chemoreceptors reported in vivo (Jänig & Koltzenburg, 1993; Moss et al. 1997; Shea et al. 2000). In the rat, bladder chemoreceptors (sensitive to capsaicin and distension with 150 mm KCl, but not to distension with 150 mm NaCl) were found mainly in hypogastric nerve. Forceful pinching was required to excite these receptors, probably indicating cushioning by overlying muscle layers or low mechanical sensitivity (Moss et al. 1997). In another study of the rat bladder, 8 of 39 distension-insensitive pelvic afferents were classified as chemoreceptors (Shea et al. 2000). Thus it is likely that high tonicity and [K+], and possibly low pH of urine are important physiological stimuli for mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors. However, since gentle stroke and touch with von Frey hairs were also strong excitatory stimuli for these mechanoreceptors, they may be activated by high-amplitude distension of the bladder in vivo. If so, hydrostatic pressure may activate these receptors directly via distortion of their endings, or act via ATP release from urothelial cells. It has been previously shown that so-called ‘volume’ receptors (which did not respond to increases in bladder wall tension) had a higher threshold than ‘in-series’ tension receptors (Morrison, 1999). It was proposed that their nerve endings are not located in muscle layer but possibly beneath the urothelium (Morrison, 1999; Namasivayam et al. 1999). In response to gentle mucosal stroking, mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors often showed bursting activity, which outlasted the period of stimulation. This could be due to release of transmitters (possibly ATP and/or acetylcholine) from the urothelium (Burnstock, 2001; Birder, 2005) which subsequently stimulate these afferents. The mechanism of transduction of their endings in the mucosa requires further investigation.

Distension-insensitive afferents: mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors

The fourth class of sensory fibres, mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors, accounted for 28% of all afferents recorded in this study. They were stretch insensitive but could be weakly activated by mucosal stroking with light von Frey hairs. In most cases they were not sensitive to hypertonic saline, α,β-methylene ATP or capsaicin. Similar percentages of so-called ‘silent afferents’ (18–28%), which do not respond to either distension or chemical stimuli were reported in vivo (Häbler et al. 1990; Jänig & Koltzenburg, 1993; Cervero, 1994; Shea et al. 2000). Some of the mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors in the present study may therefore correspond to ‘silent afferents’ reported previously. Removal of the urothelium reduced their modest sensitivity to mucosal stroking, suggesting that their endings lie within the lamina propria/urothelium. In hypersensitive bladder disorders such as interstitial cystitis, urothelial permeability is increased (Lewis et al. 1995; Elbadawi & Light, 1996). This may allow substances in the urine (high potassium, protons and high osmolarity) to directly affect bladder afferents with endings in the mucosa. In the rat bladder in vivo, changing the chemical composition of bladder contents (reduced pH, raised osmolarity and [K+]) can cause spontaneous firing and mechanosensitivity in previously silent afferents (Wen & Morrison, 1995; Morrison, 1999). Likewise, some silent afferents become loosely mechano-sensitive during acute inflammation (Jänig & Koltzenburg, 1993), possibly due to release of nerve growth factor and inflammatory mediators, such as ATP and prostaglandins (Koltzenburg & McMahon, 1995; Dmitrieva & McMahon, 1996; Rong et al. 2002; Yoshimura et al. 2002). Whether mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors can be activated by low pH or high K+, in the conditions when urothelial permeability is increased, remains to be investigated.

Conduction velocities of afferents

In this study all afferents had conduction velocities in the C fibre range (from 0.08 to 1.2 m s−1), but there were significant and consistent differences between the classes e.g. mucosal low-responding mechanoreceptors conducted about 4.5 times faster than mucosal high-responding mechanoreceptors. However, the absolute values of conduction velocity were rather slower than those reported previously in cats and rats in vivo or in vitro which included Aδ fibres (Häbler et al. 1990, 1993; Sengupta & Gebhart, 1994; Namasivayam et al. 1998; Shea et al. 2000). For example, nearly 30% of stretch-sensitive mechanoreceptors to the rat bladder conducted at more than 2.5 m s−1 (Aδ range) (Vera & Nadelhaft, 1990; Sengupta & Gebhart, 1994; Shea et al. 2000). There are few possible explanations for this discrepancy. First, there may be genuine species differences. Second, we recorded conduction velocity towards the distal end of afferent axons, whereas most studies have measured it in major nerve trunks of the pelvic or hypogastric nerves, which run back to the dorsal roots (Vera & Nadelhaft, 1990; Sengupta & Gebhart, 1994; Shea et al. 2000). Afferent axons may narrow significantly as they approach the bladder and as they branch within the wall of the bladder; they may also lose any myelin sheath (if present) before they enter the wall of the organ.

Multivariate statistical approaches

Applied multivariate statistical approaches, including discriminant analysis (Norusis, 1993; Tabachnik & Fidell, 1996), provided an objective test of the classification scheme that we initially proposed for guinea pig bladder afferents. The discriminant analysis showed about 90% success in distinguishing the four classes of bladder mechano-sensory neurons, based solely on the four parameters of spike duration, spike amplitude and responses to stretch and light stroke. Selective chemical sensitivity of bladder afferents and the location of their mechano-sensitive endings were omitted from the discriminant analysis, but clearly reinforced our ability to distinguish the four functional classes. The capability to distinguish reliably different functional classes using a parsimonious testing protocol will be valuable in assessing differential responses to drugs, inflammation and other variables in the future.

Sensitivity to capsaicin

Sensitivity to capsaicin was an additional criterion which was useful to distinguish functional classes of bladder afferents. Overall, 25% of afferents (11 from 44 units) were sensitive to 3 μm capsaicin in the guinea pig bladder. Some studies (Shea et al. 2000) have used significantly higher concentrations of capsaicin (often applied intravesically) ranging from 30 μm to 10 mm, even though the EC50 for activating TRPV1 is 0.7 μm (Caterina et al. 1997). It was reported that up to 80% of pelvic mechanoreceptors were capsaicin-sensitive in rat bladder in vivo (Shea et al. 2000). In the mouse, 67% of low threshold and 7% of high threshold distension-sensitive bladder afferents responded to 10 μm intravesical capsaicin (Daly et al. 2007). We have confirmed that many low threshold mechanoreceptors to the mouse bladder are indeed sensitive to capsaicin: 42% (8 from 19) of low threshold stretch-sensitive units were activated by capsaicin in our hands (3–10 μm) (unpublished observations). Thus, there are significant differences in the capsaicin sensitivity of the different classes of bladder afferents between these three rodents; caution should be used when extrapolating between species, including humans.

Distension-insensitive afferents: high threshold mechanoreceptors

Few distension (1–5 mm)-insensitive units, activated by compressing their receptive field with stiff von Frey hairs (2–10 mN), were recorded in this study. They may correspond to so-called ‘serosal’ or ‘mesenteric’ high threshold mechanoreceptors associated with a range of visceral organs (Jänig & Morrison, 1986; Lynn & Blackshaw, 1999; Brierley et al. 2004). High threshold mechanoreceptors have been proposed to participate in the generation of painful sensations in the visceral organs (de Groat, 1997; Brierley et al. 2004); this class needs further investigation and characterization.

Sensory pathways to the bladder

Similar to other urogenital organs, the urinary bladder has a dual sensory visceral innervation, with sensory neurons located in thoracolumbar DRG travelling via the hypogastric nerves and lumbosacral afferents projecting via pelvic nerves (Applebaum et al. 1980; Vera & Nadelhaft, 1990; Keast & De Groat, 1992). In the rat, the majority of bladder afferents are located in DRG in L6–S1, with a secondary population in L1–L2 (Applebaum et al. 1980; Vera & Nadelhaft, 1990; Keast & De Groat, 1992). Single unit recordings of colorectal afferents in the mouse from lumbar splanchnic or pelvic nerves in vitro distinguished five distinct classes of mechanoreceptors (Brierley et al. 2004). Three classes (muscle, mucosal and serosal) were common to both pathways; muscle/mucosal mechanoreceptors were only recorded in pelvic nerves and mesenteric mechanoreceptors were only found in lumbar splanchnic nerves. In the present study, recordings were made from nerve trunks distal to the pelvic ganglia (1–2 mm from the bladder) which are likely to include both pelvic/sacral and hypogastric/lumbar afferents. For this reason, we cannot be sure whether the four classes characterized here are present in both pathways. It has been reported that 93% of neurons in lumbosacral DRG of the rat were sensitive to α,β-methylene ATP application while only 50% of thoracolumbar DRG neurons respond (Dang et al. 2005). Thus it is possible that muscle-mucosal mechanoreceptors to the bladder may preferentially run in pelvic pathways as reported for muscle/mucosal mechanoreceptors found in the distal gut (Brierley et al. 2004); this remains to be tested.

In conclusion, four different functional classes of bladder mechanoreceptors have been characterized using an in vitro guinea pig bladder preparation. These results will make it possible to study, on a class-by-class basis, the physiological information conveyed by different types of bladder mechanoreceptors. Detailed characterization of major classes of bladder sensory neurons is not only important for understanding the basic physiological mechanisms of bladder sensation and reflexes but also may lead to a better strategy for selective pharmacological interventions in various bladder disorders.

Acknowledgments

This study has been supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia grant no. 375123.

References

- Applebaum AE, Vance WH, Coggeshall RE. Segmental localization of sensory cells that innervate the bladder. J Comp Neurol. 1980;192:203–209. doi: 10.1002/cne.901920202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahns E, Ernsberger U, Jänig W, Nelke A. Functional characteristics of lumbar visceral afferent fibres from the urinary bladder and the urethra in the cat. Pflugers Arch. 1986;407:510–518. doi: 10.1007/BF00657509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahns E, Halsband U, Jänig W. Responses of sacral visceral afferents from the lower urinary tract, colon and anus to mechanical stimulation. Pflugers Arch. 1987;410:296–303. doi: 10.1007/BF00580280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birder LA. More than just a barrier: urothelium as a drug target for urinary bladder pain. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F489–F495. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00467.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brierley SM, Jones RC, 3rd, Gebhart GF, Blackshaw LA. Splanchnic and pelvic mechanosensory afferents signal different qualities of colonic stimuli in mice. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:166–178. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes SJH, Chen BN, Costa M, Humphreys CMS. Initiation of peristalsis by circumferential stretch in flat sheets of guinea-pig ileum. J Physiol. 1999;516:525–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0525v.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. Purine-mediated signalling in pain and visceral perception. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:182–188. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01643-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389:816–824. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervero F. Sensory innervation of the viscera. Physiol Rev. 1994;74:95–138. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly D, Rong W, Chess-Williams R, Chapple C, Grundy D. Bladder afferent sensitivity in wildtype and TRPV1 knockout mice. J Physiol. 2007;583:663–674. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.139147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang K, Bielefeldt K, Gebhart GF. Differential responses of bladder lumbosacral and thoracolumbar dorsal root ganglion neurons to purinergic agonists, protons, and capsaicin. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3973–3984. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5239-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groat WC. A neurologic basis for the overactive bladder. Urology. 1997;50:36–52. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00587-6. discussion 53–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dmitrieva N, McMahon SB. Sensitisation of visceral afferents by nerve growth factor in the adult rat. Pain. 1996;66:87–97. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(96)02993-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downie JW, Armour JA. Mechanoreceptor afferent activity compared with receptor field dimensions and pressure changes in feline urinary bladder. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1992;70:1457–1467. doi: 10.1139/y92-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbadawi AE, Light JK. Distinctive ultrastructural pathology of nonulcerative interstitial cystitis: new observations and their potential significance in pathogenesis. Urol Int. 1996;56:137–162. doi: 10.1159/000282832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häbler HJ, Jänig W, Koltzenburg M. Activation of unmyelinated afferent fibres by mechanical stimuli and inflammation of the urinary bladder in the cat. J Physiol. 1990;425:545–562. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häbler HJ, Jänig W, Koltzenburg M. Myelinated primary afferents of the sacral spinal cord responding to slow filling and distension of the cat urinary bladder. J Physiol. 1993;463:449–460. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iggo A. Tension receptors in the stomach and the urinary bladder. J Physiol. 1955;128:593–607. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1955.sp005327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jänig W, Koltzenburg M. Pain arising from the urogenital tract. In: Maggi CA, editor. Nervous Control of the Urogenital System. Chur, Switzerland: Harwood Academic; 1993. pp. 525–578. [Google Scholar]

- Jänig W, Morrison JF. Functional properties of spinal visceral afferents supplying abdominal and pelvic organs, with special emphasis on visceral nociception. Prog Brain Res. 1986;67:87–114. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)62758-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CA, Nyberg L. Epidemiology of interstitial cystitis. Urology. 1997;49:2–9. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)80327-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keast JR, De Groat WC. Segmental distribution and peptide content of primary afferent neurons innervating the urogenital organs and colon of male rats. J Comp Neurol. 1992;319:615–623. doi: 10.1002/cne.903190411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koltzenburg M, McMahon S. Mechanically insensitive primary afferents innervating the urinary bladder. In: Gebhart G, editor. Visceral Pain, Progress in Pain Research and Management. Seattle: IASP Press; 1995. pp. 163–192. [Google Scholar]

- Kuru M. Nervous control of micturition. Physiol Rev. 1965;45:425–494. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1965.45.3.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis SA, Berg JR, Kleine TJ. Modulation of epithelial permeability by extracellular macromolecules. Physiol Rev. 1995;75:561–589. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.3.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn PA, Blackshaw LA. In vitro recordings of afferent fibres with receptive fields in the serosa, muscle and mucosa of rat colon. J Physiol. 1999;518:271–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0271r.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn PA, Olsson C, Zagorodnyuk V, Costa M, Brookes SJ. Rectal intraganglionic laminar endings are transduction sites of extrinsic mechanoreceptors in the guinea pig rectum. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:786–794. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)01050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn P, Zagorodnyuk V, Hennig G, Costa M, Brookes S. Mechanical activation of rectal intraganglionic laminar endings in the guinea pig distal gut. J Physiol. 2005;564:589–601. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.080879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milsom I, Abrams P, Cardozo L, Roberts RG, Thuroff J, Wein AJ. How widespread are the symptoms of an overactive bladder and how are they managed? A population-based prevalence study. BJU Int. 2001;87:760–766. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison JF. The activation of bladder wall afferent nerves. Exp Physiol. 1999;84:131–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-445x.1999.tb00078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss NG, Harrington WW, Tucker MS. Pressure, volume, and chemosensitivity in afferent innervation of urinary bladder in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1997;272:R695–R703. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.272.2.R695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namasivayam S, Eardley I, Morrison JFB. A novel in vitro bladder pelvic nerve afferent model in the rat. Br J Urol. 1998;82:902–905. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.00867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namasivayam S, Eardley I, Morrison JFB. Purinergic sensory neurotransmission in the urinary bladder: an in vitro study in the rat. BJU Int. 1999;84:854–860. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norusis MJ. SPSS for Windows: Professional Statistics, Release 60. Chicago,IL: SPSS Inc.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Page AJ, Blackshaw LA. An in vitro study of the properties of vagal afferent fibres innervating the ferret oesophagus and stomach. J Physiol. 1998;512:907–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.907bd.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong W, Spyer KM, Burnstock G. Activation and sensitisation of low and high threshold afferent fibres mediated by P2X receptors in the mouse urinary bladder. J Physiol. 2002;541:591–600. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta JN, Gebhart GF. Mechanosensitive properties of pelvic nerve afferent fibers innervating the urinary bladder of the rat. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:2420–2430. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.5.2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea VK, Cai R, Crepps B, Mason JL, Perl ER. Sensory fibers of the pelvic nerve innervating the rat's urinary bladder. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:1924–1933. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.4.1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart WF, Van Rooyen JB, Cundiff GW, Abrams P, Herzog AR, Corey R, Hunt TL, Wein AJ. Prevalence and burden of overactive bladder in the United States. World J Urol. 2003;20:327–336. doi: 10.1007/s00345-002-0301-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnik BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. New York: Harper Collins; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Vera PL, Nadelhaft I. Conduction velocity distribution of afferent fibers innervating the rat urinary bladder. Brain Res. 1990;520:83–89. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91693-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen J, Morrison JF. The effects of high urinary potassium concentration on pelvic nerve mechanoreceptors and ‘silent’ afferents from the rat bladder. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;385:237–239. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1585-6_29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura N, Seki S, Chancellor MB, de Groat WC, Ueda T. Targeting afferent hyperexcitability for therapy of the painful bladder syndrome. Urology. 2002;59:61–67. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01639-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagorodnyuk VP, Brookes SJ. Transduction sites of vagal mechanoreceptors in the guinea pig esophagus. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6249–6255. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06249.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagorodnyuk VP, Costa M, Brookes SJ. Major classes of sensory neurons to the urinary bladder. Auton Neurosci. 2006;126–127:390–397. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagorodnyuk VP, Lynn P, Costa M, Brookes SJ. Mechanisms of mechanotransduction by specialized low-threshold mechanoreceptors in the guinea pig rectum. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G397–G406. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00557.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]