Abstract

To detect joint movement, the brain relies on sensory signals from muscle spindles that sense the lengthening and shortening of the muscles. For single-joint muscles, the unique relationship between joint angle and muscle length makes this relatively straightforward. However, many muscles cross more than one joint, making their spindle signals potentially ambiguous, particularly when these joints move in opposite directions. We show here that simultaneous movement at adjacent joints sharing biarticular muscles affects the threshold for detecting movements at either joint whereas it has no effect for non-adjacent joints. The angular displacements required for 70% correct detection were determined in 12 subjects for movements imposed on the shoulder, elbow and wrist at angular velocities of 0.25–2 deg s−1. When moved in isolation, detection thresholds at each joint were similar to those reported previously. When movements were imposed on the shoulder and wrist simultaneously, there were no changes in the thresholds for detecting movement at either joint. In contrast, when movements in opposite directions at velocities greater than 0.5 deg s−1 were imposed on the elbow and wrist simultaneously, thresholds increased. At 2 deg s−1, the displacement threshold was approximately doubled. Thresholds decreased when these adjacent joints moved in the same direction. When these joints moved in opposite directions, subjects more frequently perceived incorrect movements in the opposite direction to the actual. We conclude that the brain uses potentially ambiguous signals from biarticular muscles for kinaesthesia and that this limits acuity for detecting joint movement when adjacent joints are moved simultaneously.

Accurate and coordinated motor control relies on sensory information about the positions and movements of joints. For many human joints, movement sensibility has been determined by passively rotating the joint in isolation to determine the level at which the movement is reliably detected. This long-established technique (Goldscheider, 1889) shows that detection thresholds, when measured in terms of angular displacements, tend to increase moving distally from shoulder to elbow to finger (Hall & McCloskey, 1983) and from hip to knee to ankle in the lower limb (Refshauge et al. 1995).

Mechanoreceptors in joints, skin and muscle can all contribute to the sensation of joint movement (Gandevia & McCloskey, 1976; Ferrell et al. 1987; Clark et al. 1989; Collins et al. 2005). The contribution of muscular receptors, originally demonstrated by tendon vibration (Goodwin et al. 1972a,b), can be shown by differences in movement detection thresholds when the muscle tendon is disengaged (Gandevia & McCloskey, 1976; McCloskey et al. 1983), during anaesthesia of joint and skin (Gandevia & McCloskey, 1976; Clark et al. 1986), with prior muscle contraction to condition muscle stretch receptors (Wise et al. 1996), and by the effects of muscle contraction during the imposed movement (Taylor & McCloskey, 1992; Wise et al. 1998). The ensemble of muscle spindle discharge arising from all synergistic muscles provides the net signal of joint movement (Verschueren et al. 1998). When expressed in terms of the proportional change in average muscle fascicle lengths for the muscles crossing a joint, detection thresholds are similar across all limb joints, indicating that fascicle length and shortening as signalled by muscle spindles is a variable of interest to the brain for estimating joint movement (Refshauge et al. 1998).

The movements we make in many normal activities, for example reaching movements, almost always involve the simultaneous rotation of more than one joint in a limb. When we reach forward to grasp an object there is simultaneous flexion of the shoulder, extension of the elbow and wrist and flexion of the fingers. Throughout the body, many muscles are biarticular, crossing more than one joint and therefore having actions at more than one joint. In the upper limb, for example, there are wrist and finger extensors that also extend the elbow and wrist flexors that flex the elbow. Since the brain uses signals of muscle length and shortening to detect joint movement, there is a potential for ambiguity and interaction at the receptor level when there is simultaneous movement of two joints that share a muscle. There is also a potential for interaction within the central nervous system when more than one joint is moved regardless of shared musculature. The present study investigates these possibilities by determining thresholds for detecting movements imposed simultaneously on two upper-limb joints. Specifically, detection levels for the wrist, elbow and shoulder, when moved in isolation, are compared with those when another joint is moved simultaneously. The wrist-elbow combination examines joints that have muscles in common whereas the wrist-shoulder combination examines joints that have no muscles in common.

Methods

Fifteen healthy adults provided written informed consent before participating in these simple, non-invasive experiments that had been approved by the institute's human ethics committee in accord with the Declaration of Helsinki. Two studies are described. In the first, movements are imposed on the shoulder and wrist and in the second on the elbow and wrist.

Set-up

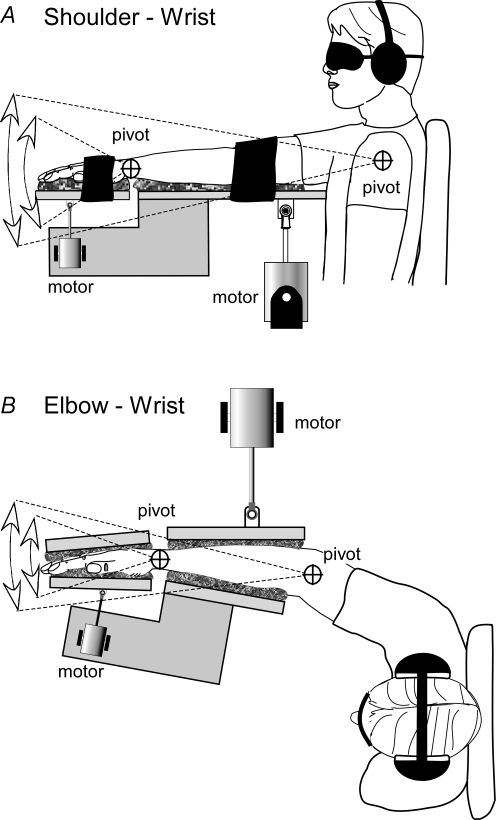

In the shoulder–wrist study, 12 subjects aged 25–45 years (7 male, 11 right handed) participated. They sat comfortably with the back braced in a stable chair that did not impinge on the shoulder. They were blindfolded and wore ear defenders to exclude visual and auditory cues. The right arm was extended directly in front at shoulder level, the arm resting on a padded support with the wrist pronated (Fig. 1A). The support had pivot points that allowed rotation in the vertical plane about both the shoulder and wrist joints. Two servomotors under independent computer control were used to impose movements on the joints. The motor that moved the wrist was mounted on the support for the upper arm so that precise independence of the two joint rotations was achieved. Subjects and the support were positioned so that the axes of rotation of the support were aligned with the axes of rotation of the shoulder and wrist. Foam-padded straps were applied across the upper arm and hand, to hold the arm in position. All parts of the support in contact with the arm were padded with foam to prevent movement of the support against the skin and eliminate cutaneous cues.

Figure 1. Experimental set-up.

Two studies were designed to test the effects of simultaneous movement at non-adjacent and adjacent joints. A, in the shoulder–wrist study, small threshold-level movements were imposed on the non-adjacent shoulder and wrist joints, either in isolation or simultaneously, in a vertical plane. Independent control was achieved by mounting the wrist motor on the arm support. The axes of rotation of the supports were collinear with the axes of the joints (pivot). B, in the elbow–wrist study, movements were imposed on the adjacent elbow and wrist joints in the same way, either in isolation or simultaneously, in the horizontal plane.

In the elbow–wrist study, 12 subjects aged 23–45 years (9 male, 11 right handed), nine of whom had participated in the shoulder–wrist study, were tested. They sat in the chair as above with the forearm semipronated so that the palm of the hand was vertical. The hand and forearm were secured between separate padded supports. As in the shoulder–wrist study, pivot points aligned with the axes of the wrist and elbow could be locked or driven independently by servomotors. The elbow was positioned at 40 deg of flexion at the start of each trial (Fig. 1B) and both movements were applied in the horizontal plane.

It should be noted that the different planes of rotation between studies were chosen for practical reasons. The movements of the two joints being tested had to be in the same plane to avoid confusion in reporting. Thus, the semipronated arm posture was used for the elbow–wrist study. Clamping the entire limb in the shoulder–wrist study to achieve the same posture as in the elbow–wrist study produced unacceptable drag of the skin on the support and so, instead, vertical movements were tested. Vertical movement introduces the possibility that movement-related gravitational forces on the limb could assist movement detection. With the arm horizontal and at the amplitudes tested here, the effects are minute (< 0.0002 g) and unlikely to affect absolute detection levels. Most importantly, there will be no effect on the interaction when both joints are moved simultaneously because the detection levels are controlled for by the isolated limb movements.

Protocol

In the shoulder–wrist study, four thresholds for movement detection were measured in separate sessions. In two of these, movements were imposed on just one joint, either (i) the shoulder or (ii) the wrist, and detection thresholds at different movement velocities were determined for that joint. In the other two sessions, movements of the same angular velocity, displacement and direction were imposed on two joints simultaneously: (iii) the threshold for detecting wrist movement when there was simultaneous movement of the shoulder by the same angular rotation in the opposite direction, and (iv) the threshold for detecting shoulder movement when there was simultaneous movement of the wrist by the same angular rotation in the opposite direction. The elbow–wrist study proceeded similarly with detection thresholds determined for each joint when moved in isolation and when the other was moved simultaneously by the same angular rotation in the opposite direction. Each of the eight testing sessions took about 2 h to complete.

Following observations made in the elbow–wrist study, an additional study was undertaken in eight of the subjects to determine the effects on detection thresholds at the wrist with simultaneous elbow movements, this time in the same direction as the wrist rather than the opposite direction. Thresholds were determined for the four velocities using the same protocol and setup.

Movement detection thresholds were determined using the established method of Goldscheider (1889) as modified by Cleghorn & Darcus (1952). At a random time (2–5 s) after a ‘ready’ indicator, a ramp and hold movement at a given test velocity and displacement was imposed on the joint being tested, starting from a standard initial position. Subjects were asked to report the direction of any movement they perceived. Three seconds was allowed for a response after completion of a movement so that reaction time was not a factor. After the 3 s interval, the motor made a faster (10 deg s−1) return to the start position. A response of the correct direction was recorded as ‘detected’ whereas no response or a wrong direction was recorded as a ‘undetected’.

Each displacement magnitude that was tested was presented 20 times, 10 flexions and 10 extensions in randomised order, with a 10–15 s gap between. If less than 14 responses were correct (70%) the next test displacement was increased. If more than 14 responses were correct the next displacement was decreased. This continued until either an exact 70% correct detection was obtained or the displacement required for 70% correct lay between two tested displacements separated by no more than 0.01 deg, the minimum resolution of interest. In the latter situation, the 70% detection level was determined by linear interpolation. By this method, the angular displacement required for 70% correct detection of the direction of movement was obtained for four different movement speeds (0.25, 0.5, 1, 2 deg s−1), which were tested in random order during each session.

Subjects were given several practice trials at the beginning of the experiment with the eyes open then shut to ensure that they understood the protocol. Throughout testing, they were frequently reminded to respond only when they were certain of the direction and not to guess. To standardize effects of muscle spindle history, subjects made a brief cocontraction of the arm muscles prior to each test movement, relaxing them completely before testing.

Measurement and analysis

Detection thresholds are described by averages (± s.e.m.) across subjects for each joint and condition (isolated or simultaneous movement). For each study, a 3-way ANOVA (joint × simultaneous movement × velocity) with Holm–Sidak post hoc comparison testing was applied to identify significant effects of simultaneous joint movement. ANOVA of data from the nine common subjects was used to determine if the plane of motion, vertical or horizontal, affected detection thresholds at the wrist. The additional elbow–wrist study that examined the effects of elbow movement in the same direction as the wrist was analysed by separate ANOVA because not all subjects were available. The frequency of responses of movements in the wrong direction was analysed by Student's paired t test (joint × simultaneous movement) and binomial probabilities. Throughout, Pα was set at 0.05.

Results

Consistent with previous data (Hall & McCloskey, 1983), detection thresholds at the shoulder, elbow and wrist decreased as movement velocity increased, whether or not there was simultaneous movement at another joint (Figs 2 and 3). Overall, movements detected at 2 deg s−1 were one-fifth the size of movements detected at 0.25 deg s−1. Inspection of the data showed that the relationships between the logarithm of the displacement and the logarithm of the velocity were approximately linear so ANOVAs were performed on the 70% detection levels after logarithmic transform. Consistent with all previous studies of this type, subjects varied considerably in their detection thresholds at every joint and condition tested, showing more than a twofold difference between the mean levels of the best and worst performers across velocities and joints (F11,384= 7.0, P < 0.001 by single factor ANOVA).

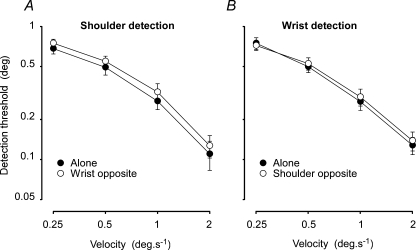

Figure 2. Detection thresholds for wrist and shoulder.

Displacements required for reliable detection at different movement velocities for the shoulder with and without simultaneous movement of the wrist (A) and the wrist with and without simultaneous movement of the shoulder (B). Data are means ± s.e.m. for 12 subjects. Similar angular displacements could be detected at both joints and simultaneous movement had no significant effect at either joint.

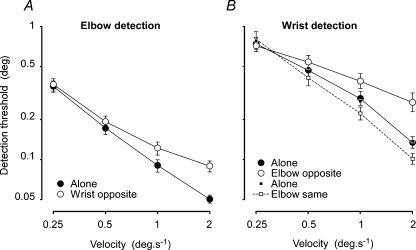

Figure 3. Detection thresholds for wrist and elbow.

Displacements required for reliable detection at different movement velocities for the elbow with and without simultaneous movement of the wrist in the opposite direction (A) and the wrist with and without simultaneous movement of the elbow in the opposite direction (large circles) (B). Data are means ± s.e.m. for 12 subjects. Detection thresholds were at smaller displacements for the elbow than the wrist. For both elbow and wrist, simultaneous movement of the other joint in the opposite direction increased detection thresholds, with the greatest effect at higher movement velocities (compare open with filled circles). Eight subjects (small open squares) were also tested with simultaneous movement of the elbow in the same direction. This decreased detection thresholds compared with the *wrist-alone (small filled squares) thresholds for this subgroup.

Shoulder–wrist

Mean detection levels (± s.e.m.) for the four conditions of the shoulder–wrist experiment are shown in Fig. 2. Threshold detection levels, in degrees of joint rotation, were very similar and statistically indistinguishable (F1,176= 0.58) for the shoulder and wrist joints across the range of velocities tested. At both the shoulder and wrist, subjects could perceive smaller displacements with higher movement velocities (F3,176= 98, P < 0.001). At 2 deg s−1, subjects could detect displacements less than 20% of that required for detection at 0.25 deg s−1.

There was no significant effect of imposing a simultaneous movement on the other joint (F1,176= 2.5). Although this level can be described as of marginal statistical significance (P = 0.11), any effect appears to be small and of little significance physiologically (Fig. 2, compare open and filled symbols).

Elbow–wrist

The elbow–wrist study was conducted with the hand aligned semiprone and moving in the horizontal plane, rather than moving up and down as it was in the shoulder–wrist experiment. Despite this, considering wrist movement without simultaneous movement of the other joint, there was no significant difference between the detection levels measured at the wrist during the two studies (F1,24= 0.03). Thresholds varied significantly between subjects (F1,24= 35.7, P < 0.001), but there was no significant subject–study interaction, which indicates that the results between the two testing sessions were reproducible on a subject by subject basis.

Mean detection levels for the four conditions of the elbow–wrist experiment are shown in Fig. 3. Across all movement velocities, subjects could detect movements at the elbow of about half the angular displacement required for detection at the wrist (F1,176= 32, P < 0.001) and for every subject the detection level averaged across movement velocities was smaller at the elbow than at the wrist (range 23–63%).

For both the wrist and elbow, detection thresholds increased when there was simultaneous movement of the other joint in the opposite direction (Fig. 3; F1,176= 22.1, P < 0.001). However, this effect was velocity dependent, there being no significant effect at the slowest velocity (0.25 deg s−1) but an approximate doubling of the movement required for detection at a velocity of 2 deg s−1. With simultaneous movement of the elbow in the same direction, wrist detection thresholds decreased for the eight subjects tested (Fig. 3B, dashed line; F1,21= 69.9, P < 0.001, ANOVA by subject, velocity, simultaneous movement).

Wrong responses

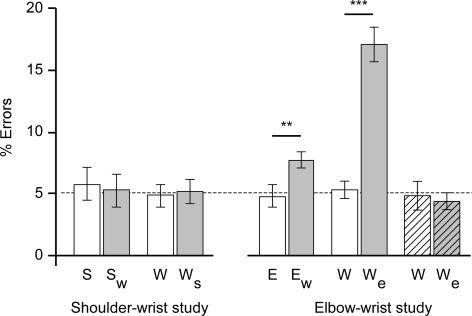

For the movements applied on just one joint, the frequency of reports of movement in the wrong direction was 5.18%± 0.49 (n = 48, for the wrist, elbow and shoulder). However, for trials in which subjects nominated wrist movement while there was simultaneous elbow movement in the opposite direction (Fig. 4), subjects reported the wrong direction on 17.1%± 1.4 of occasions, significantly more than for the wrist with no simultaneous elbow movement (paired students t: t11= 8.3, P < 0.001). Although to a lesser degree (7.7%± 0.7), there was also a significant increase in wrong-direction calls when detecting elbow movements with simultaneous wrist movement in the opposite direction (paired t11= 3.9, P < 0.001). When simultaneous elbow movement was in the same direction, the frequency of wrong calls was not different from the wrist only trials (paired t7= 0.51).

Figure 4. Frequency of reports of movement in the wrong direction.

Frequency (± s.e.m.) of reporting the wrong direction of imposed movements for the shoulder–wrist (left) and the elbow–wrist (right) studies. For the single joint movements (S, W, E, W), the shoulder with wrist movement (Sw) and the wrist with shoulder movement (Ws), this rate was a constant 5% level. For the elbow with wrist movement (Ew) and wrist with simultaneous elbow movement (We) in opposite directions, wrong reports were significantly more frequent. (**P < 0.01). Simultaneous movements in the same direction did not alter the frequency of detecting wrong directions (right hatched bars).

For the ‘wrist with simultaneous elbow movement’ trial, the movements were tallied to determine if the large number of wrong responses arose with wrist movements of flexion or extension. Across all subjects, there was no significant difference between the mean percentage of wrong responses for the different directions (binomial P = 0.11). However, there were marked differences in the results from individual subjects. Subjects were split approximately equally in this direction effect. Six reported a significantly higher number of wrong responses when the joints moved in the same direction, and five gave a significantly higher number of wrong responses when the joints moved in same directions (binomial P < 0.01 for each subject). Only one subject gave similar numbers of wrong responses in each direction.

Discussion

These results show that movement detection at the adjacent elbow and wrist joints is affected by simultaneous movement of the other joint, whereas movement detection is not affected by simultaneous movement of non-adjacent shoulder and wrist joints. For the elbow and wrist, thresholds for detecting movement increased when the other joint moved in the opposite direction. The simplest explanation for these observations is that the interference occurs at the level of the sensory receptors in muscles that cross adjacent joints. Oppositely directed simultaneous movements will tend to stretch one end while shortening the other end of biarticular muscles, resulting in a net reduction, and in some situations a reversal, of the overall muscle stretch or shortening that would occur when only one joint moved. The corollary prediction, which was confirmed here, is that when the adjacent elbow is moved in the same direction as the wrist, greater reciprocal stretch and shortening of the forearm flexor and extensor muscles would result in movements being detected at smaller thresholds than when only the wrist was moved.

Detection thresholds

Consistent with previous reports was our finding that movement detection levels decreased with velocity. Across all joints, 10-fold increases in velocity yielded approximately the same improvement in detection threshold, which is likely to reflect the sensitivity of muscle spindles to the velocity of stretch (Matthews & Stein, 1969).

In terms of the size of responses, the thresholds reported for joints moved in isolation here were similar for the shoulder and wrist whereas movements of half the size could be detected at the elbow across these velocities. These detection levels at the shoulder are consistent with those reported by Hall & McCloskey (1983) but at the elbow they were approximately half the size. At the wrist, detection levels were about half the size reported in the earlier studies of Goldscheider (1889), Laidlaw & Hamilton (1937) and Cleghorn & Darcus (1952). These previous studies were performed before the phenomenon of preconditioning muscle spindles by a brief contraction had been described (Wise et al. 1998). This technique was used in the present study to standardize muscle history but it also increases the response of muscle spindles to stretch (Proske et al. 1992; Wilson et al. 1995). Since this was done for the forearm but not the upper arm muscles, it provides a likely explanation for the lower thresholds at the elbow and wrist, but not the shoulder, compared with the previous studies.

The shoulder–wrist and elbow–wrist experiments were conducted with wrist movements in different planes. Previous reports suggest that this different alignment relative to the gravitational vector could affect movement sense through the change in the gravitational moment acting on the limb (Worringham & Stelmach, 1985; Winter et al. 2005). However, these studies investigated position sense rather than movement sense and involved much larger changes in joint angle. Consistent with the negligible changes in the gravitational moment for the movements delivered in the present study, there was no detectible difference in the detection thresholds for wrist movement for the two planes of movement.

Interaction between adjacent joints

Detection thresholds at the wrist were affected by simultaneous motion of the elbow, but not the shoulder. However, this effect existed only for velocities of more than 0.25 deg s−1 with the greatest effect at the fastest movement velocity.

Joint receptors may have contributed to movement detection, although they are not likely to have been a major source of information in these experiments. Joint receptors are most responsive to movements at the extremes of joint movement (Ferrell et al. 1987; Ferrell & Smith, 1988). Our trials were conducted at neutral joint positions and movements were small, so that the input from joint receptors was likely to be minor. Furthermore, as joint receptors are specifically activated only by rotation of the joint in question, they are unlikely to hold the explanation for the interaction between the elbow and wrist observed here.

Cutaneous receptors can also contribute to kinaesthesia. Collins et al. (2005) demonstrated that skin stretch at the elbow can produce kinaesthetic illusions. Their stretch stimuli resulted in 2–8% skin strain (Collins & Prochazka, 1996). Although much greater than the skin strain produced by the threshold level movements of the present study, it is conceivable and easily seen by stretching the skin over the dorsum of the wrist that cutaneous receptors could be activated by distant skin stretch. However, this could not contribute to the interaction observed when the elbow and wrist were moved simultaneously because the support of the forearm prevented transmission of any stretch from one joint to another.

Muscle receptors are likely to provide the main source of information responsible for the detection threshold changes seen during simultaneous joint movements in these experiments. Primary receptors of muscle spindles demonstrate high sensitivity to small changes in length, while secondary receptors are suited to signal velocity (Matthews & Stein, 1969; Goodwin et al. 1975; Vallbo et al. 1979). The signal of joint kinematics comes from a weighted ensemble response of the spindles in all of the muscles crossing a joint (Verschueren et al. 1998). Eight of the 10 muscles that cross the elbow also cross the wrist, the exceptions being flexor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis longus, and components of the long finger flexors. Thus, when the elbow is moved, most of the muscles crossing the wrist are affected. Oppositely directed simultaneous movements at the elbow and wrist would tend to stretch one end of a biarticular muscle and shorten the other end, resulting in a diminished, and possibly reversed, signal from muscle spindles. Signals from the eight biarticular muscles of the wrist and elbow therefore present a potential for ambiguity and interaction when both joints are moved. The control experiment, which paired the shoulder and wrist because they share no muscles, showed no interaction with simultaneous movement. Thus, these results support the hypothesis of receptor level interference, as significant increases in wrist detection thresholds were found when there was simultaneous movement of the elbow in the opposite direction.

Sensitivity for detecting joint movement improves with increasing velocity. The effect of interference across adjacent joints also depended on the velocity of the imposed movement, with no detectable effect at the slowest velocity (0.25 deg s−1) and the largest effect at the fastest velocity (2 deg s−1). If we conclude that ambiguity in the muscle spindle response is responsible for the interference, this result indicates that spindles make the greater contribution to detecting faster movements, consistent with the high sensitivity of spindles to stretch velocity (Matthews & Stein, 1969). At very slow velocities, typically less than 0.1 deg s−1, subjects use strategies based on detecting joint position rather than joint movement (Clark et al. 1985; Taylor & McCloskey, 1990). Non-muscular receptors might provide proportionately more information for detecting slower joint movements. Still, consistent with the spindle sensitivity to absolute length (Newsom Davis, 1975), position sense also relies heavily on muscles receptors (Clark et al. 1985). The present result therefore suggests that the subpopulation of spindle receptors that provide for static joint position sense (e.g. secondary endings) are not subject to the interference produced by movement at an adjacent joint. Static and dynamic fusimotor effects on spindle output (Crowe & Matthews, 1964) should not have an influence here as the muscles were at rest throughout the imposed movements although the prior brief contraction (typically about 15 s before the movement) could have left some residual fusimotor drive (Wilson et al. 1995).

As noted in other studies, subjects can perceive that some movement occurs before they are certain of its direction (Laidlaw & Hamilton, 1937; Hall & McCloskey, 1983). However, simple event detection can be based on non-specific cues rather than proprioceptive cues about movement. Therefore, subjects were instructed to respond only when they were certain of the direction of the imposed movement. The 70% level was chosen because, with the ‘guessing’ rate kept low by the instruction to subjects, there is a 5% probability of achieving this in 10 trials by guessing alone. In previous studies from this and other laboratories, subjects named the wrong direction (i.e. false positives) with approximately 5% of presented stimuli, and this has remained relatively constant. This rate was repeated again here for the studies in which just one joint was moved, confirming that subjects did resist guessing as instructed. However, when the elbow and wrist were moved simultaneously, the rate increased, and this was most pronounced when reporting movements of the wrist (Fig. 4). Without reason to believe that subjects altered their ‘guessing rate’ in these trials, we can infer that they did in fact perceive the movement at the test joint to be in the opposite direction when the adjacent joint moved in the opposite direction. Thus, simultaneous movement of the adjacent joint appears to have affected the signal attributed to the test joint more than the movement of the test joint itself.

It is not easy to explain why twice as many wrong responses were made for wrist movements as for elbow movements. At the mean wrist and elbow angles tested, a simple biomechanical model indicates that muscle fibre length of flexor carpi radialis changes 0.27 mm per degree of wrist rotation and 0.12 mm per degree of elbow rotation, with similar coupling in the other biarticular muscles (Gonzalez et al. 1997; Holzbaur et al. 2005). This implies that the wrist movement would dominate with opposite rotations of wrist and elbow. Therefore, reports of wrong direction should be greater at the elbow rather than at the wrist, which was not the case. In addition, it also suggests that movement detection should be more acute at the wrist than the elbow in terms of joint angle, which also was not the case. Can we explain this? The hypothesis that we will pursue is the effects of the tendon coupling. The long tendon of the extensor hallucis has a slack or dead space that reduces movement sensitivity at the big toe because the initial part of the movement is not transmitted to the muscle (Refshauge et al. 1998). As the long tendons of the biarticular, wrist-elbow muscles are at the wrist end, effects of tendon coupling will be seen more at the wrist than at the elbow. Furthermore, contrary to the assumption of proprioceptive studies to date, tendons are compliant so that fascicle movement does not accurately reflect joint movement and this has been shown to be a significant factor that the brain must deal with when controlling joint posture (Loram et al. 2005). The tendon compliance itself will introduce an asymmetry in the wrist versus elbow delivery of joint movement to the spindle as the short-range series stiffness, which is greater than the tendon stiffness, lies in the contractile element (Loram et al. 2007a,b) and we would have maximized this by our preconditioning protocol. This result will force a rethink of the theory advanced by McCloskey and colleagues, which proposes that kinaesthetic thresholds are determined by proportional changes in muscle fibre lengths (Hall & McCloskey, 1983; Refshauge et al. 1995; Refshauge et al. 1998). This theory is based largely on the increase in angular thresholds seen when moving from proximal to distal limb joints. However, this change in thresholds is also in accord with the pattern of longer and more compliant tendons when moving from proximal to distal muscles.

Removing one of the agonist or antagonist muscle groups reduces proprioceptive acuity (Gandevia et al. 1983) and the illusion of joint rotation achieved by tendon vibration is moderated or eliminated by the vibration of antagonistic muscles (Gilhodes et al. 1986). Thus, the sensation of movement at a joint is derived from a central processing of the proprioceptive inflow obtained from both the flexor and extensor muscles. Taylor & McCloskey (1992) found an asymmetry in detection of flexion and extension at the elbow, which they attributed to a difference between the afferent discharges from the agonist and antagonist muscles. However, in addition to a difference in the responses between muscles, it also implies an asymmetry in the responses to muscle lengthening and shortening, which is apparent in relaxed muscles in which a large proportion of the spindle primary afferents are silent but do respond to muscle stretch (Wilson et al. 1995). Across the entire group of subjects, post hoc inspection of our data did not show a difference between the proportion of flexion and extension movements that were missed (i.e. the 30% of negatives obtained with the 70% correct reports at the threshold level). However, we did observe that the direction of imposed movements that produced reports of movement in the wrong direction had a significant effect. Furthermore, the direction was not consistent between subjects; some were affected by flexion whereas others were equally affected by extension. This is as if subjects preferentially attended to one muscle group or the other. It could be that this was just an idiosyncratic preference but there are other factors that could produce this result. One explanation is muscle spindle thixotropy (Gregory et al. 1998; Wise et al. 1998). In making the brief cocontraction of the arm muscles to standardize muscle spindle history prior to each test, some subjects may have contracted the flexors more effectively whereas others contracted the extensors more effectively. The resulting imbalance in the resting discharge of the muscle spindles and responses to movement would mean that one group would have the dominant effect on the perceived movement. Another possibility is that the particular posture for each subject subtly altered the compliance of the tendon couplings to the joint and the alignments of the biarticular forearm muscles relative to the elbow and wrist, factors which influence proprioceptive acuity (Refshauge & Fitzpatrick, 1995; Gooey et al. 2000).

Could this interaction be due to central rather than peripheral mechanisms? The shoulder–wrist experiment shows that subjects can attend to movements of these joints independently, as the movement detection levels at each joint were unaffected by movement of the other. Sensory masking of one proprioceptive input by the other, which would be expected to increase detection thresholds, appears not to have an effect for these small threshold-level movements. This indicates that central interference at a cortical level is not the explanation for the altered detection levels at the wrist and elbow when the other joint is moved. However, although we cannot find direct evidence for it, it remains possible that the somatotopic proximity of the elbow–wrist compared with the shoulder–wrist pairing could lead to ambiguity regarding the joint that is moving and its direction through overlap of receptive fields of the somatosensory cortex (Calford & Tweedale, 1991; Fitzgerald et al. 2004). We have to accept that the perfect elbow–wrist control experiment that would exclude a central interaction is not available through this approach. The point may to some extent be academic as a peripheral interaction would be likely to give rise to a central interaction.

Significance

These threshold results are important for our understanding of the sensory control of posture and movement. Although the movement amplitudes and velocities tested here appear small and slow, they are of the same order as the residual movements that exist when we attempt to control posture (e.g. see Fitzpatrick & McCloskey (1994). This study shows that the brain uses potentially ambiguous signals from biarticular muscles for kinaesthesia and that this limits acuity for detecting joint movement when adjacent joints are moved simultaneously. The likely mechanism for this limitation is that the signal from biarticular muscles is, in part, ambiguous as to which joint it refers. Multiarticular muscles exist throughout the body and it is reasonable to expect that this phenomenon also applies at other joints, although the specific interactions may vary according to the morphology, biomechanics and function of different joint combinations. For these externally imposed movements, we can assume that we see here the extent to which the brain can remove ambiguity by attending to or increasing the weighting of signals from mono-articular muscles, cutaneous and joint receptors.

The way ambiguous signals are handled by the CNS could be different for joint movements driven by muscle activation, and could also differ between voluntary movements based on perception and the more reflexive automatic levels of muscle activation. During active movements of multiple joints having shared muscles, the brain might remove ambiguity by attending to or weighting sensory input from monoarticular muscles if that enables better control of a desired movement. When movement at just one joint is required, it seems reasonable to assume that motor drive would be directed towards the appropriate monoarticular muscles. Increased spindle sensitivity through fusimotor drive to these muscles would be a natural consequence that might decrease the potential ambiguity from biarticular muscles.

Movements of the limbs, such as reaching, and postural movements of the spine usually require the joints to be either all extended or all flexed. Combinations such as extension of the wrist with flexion of the elbow are probably executed infrequently and are difficult to perform, which is likely to be related to the large number of biarticular muscles. Along with this, multiarticular synergies that are performed frequently would become entrained according to neural learning principles. The brain may be concerned with patterns of muscle lengthening as they relate to the entire movement of the limb rather than using the information for explicit control on a joint-by-joint basis. Thus, loss of information about movement of individual joints may not have a large effect on the proprioceptive control of the trajectory of the distal end of the limb as a sensory underestimation of movement at one joint tends to be accounted for by an overestimation at another. In this way, the degrees of freedom that must be controlled in these multiarticular movements is significantly reduced.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Prince of Wales Medical Research Institute and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

References

- Calford MB, Tweedale R. Acute changes in cutaneous receptive fields in primary somatosensory cortex after digit denervation in adult flying fox. J Neurophysiol. 1991;65:178–187. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.65.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark FJ, Burgess RC, Chapin JW. Proprioception with the proximal interphalangeal joint of the index finger. Evidence for a movement sense without a static-position sense. Brain. 1986;109:1195–1208. doi: 10.1093/brain/109.6.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark FJ, Burgess RC, Chapin JW, Lipscomb WT. Role of intramuscular receptors in the awareness of limb position. J Neurophysiol. 1985;54:1529–1540. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.54.6.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark FJ, Grigg P, Chapin JW. The contribution of articular receptors to proprioception with the fingers in humans. J Neurophysiol. 1989;61:186–193. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.61.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleghorn T, Darcus H. The sensibility to passive movement of human elbow joint. Q J Exp Psychol. 1952;4:66–77. [Google Scholar]

- Collins DF, Prochazka A. Movement illusions evoked by ensemble cutaneous input from the dorsum of the human hand. J Physiol. 1996;496:857–871. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins DF, Refshauge KM, Todd G, Gandevia SC. Cutaneous receptors contribute to kinesthesia at the index finger, elbow, and knee. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:1699–1706. doi: 10.1152/jn.00191.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe A, Matthews PB. The effects of stimulation of static and dynamic fusimotor fibres on the response to stretching of the primary endings of muscle spindles. J Physiol. 1964;174:109–131. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1964.sp007476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell WR, Gandevia SC, McCloskey DI. The role of joint receptors in human kinaesthesia when intramuscular receptors cannot contribute. J Physiol. 1987;386:63–71. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell WR, Smith A. Position sense at the proximal interphalangeal joint of the human index finger. J Physiol. 1988;399:49–61. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald PJ, Lane JW, Thakur PH, Hsiao SS. Receptive field properties of the macaque second somatosensory cortex: evidence for multiple functional representations. J Neurosci. 2004;24:11193–11204. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3481-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick R, McCloskey DI. Proprioceptive, visual and vestibular thresholds for the perception of sway during standing in humans. J Physiol. 1994;478:173–186. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandevia SC, Hall LA, McCloskey DI, Potter EK. Proprioceptive sensation at the terminal joint of the middle finger. J Physiol. 1983;335:507–517. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandevia SC, McCloskey DI. Joint sense, muscle sense, and their combination as position sense, measured at the distal interphalangeal joint of the middle finger. J Physiol. 1976;260:387–407. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilhodes JC, Roll JP, Tardy-Gervet MF. Perceptual and motor effects of agonist-antagonist muscle vibration in man. Exp Brain Res. 1986;61:395–402. doi: 10.1007/BF00239528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider A. Untersuchungen über den muskelsinn. Arch Anat Physiol. 1889;3:369–502. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez R, Buchanan T, Delp S. How muscle architecture and moment arms affect wrist flexion-extension moments. J Biomech. 1997;30:705–712. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(97)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin GM, Hulliger M, Matthews PB. The effects of fusimotor stimulation during small amplitude stretching on the frequency-response of the primary ending of the mammalian muscle spindle. J Physiol. 1975;253:175–206. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp011186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin GM, McCloskey DI, Matthews PB. The contribution of muscle afferents to kinaesthesia shown by vibration induced illusions of movement and by the effects of paralysing joint afferents. Brain. 1972a;95:705–748. doi: 10.1093/brain/95.4.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin GM, McCloskey DI, Matthews PB. A systematic distortion of position sense produced by muscle vibration. J Physiol. 1972b;221:8P–9P. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooey K, Bradfield O, Talbot J, Morgan DL, Proske U. Effects of body orientation, load and vibration on sensing position and movement at the human elbow joint. Exp Brain Res. 2000;133:340–348. doi: 10.1007/s002210000380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory JE, Wise AK, Wood SA, Prochazka A, Proske U. Muscle history, fusimotor activity and the human stretch reflex. J Physiol. 1998;513:927–934. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.927ba.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall LA, McCloskey DI. Detections of movements imposed on finger, elbow and shoulder joints. J Physiol. 1983;335:519–533. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzbaur K, Murray W, Delp S. A model of the upper extremity for simulating musculoskeletal surgery and analyzing neuromuscular control. Ann Biomed Eng. 2005;33:829–840. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-3320-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laidlaw RW, Hamilton MA. A study of thresholds in apperception of passive movement among normal control subjects. Bull Neurol Inst New York. 1937;6:268–273. [Google Scholar]

- Loram ID, Maganaris CN, Lakie M. Active, non-spring-like muscle movements in human postural sway: how might paradoxical changes in muscle length be produced? J Physiol. 2005;564:281–293. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.073437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loram I, Maganaris C, Lakie M. The passive, human calf muscles in relation to standing II: the short range stiffness lies in the contractile component. J Physiol. 2007a;584:677–692. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.140053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loram I, Maganaris C, Lakie M. The passive, human, calf muscles in relation to standing I: the non-linear decrease from short range to long range stiffness. J Physiol. 2007b;584:661–675. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.140046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews PB, Stein RB. The sensitivity of muscle spindle afferents to small sinusoidal changes of length. J Physiol. 1969;200:723–743. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1969.sp008719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey DI, Cross MJ, Honner R, Potter EK. Sensory effects of pulling or vibrating exposed tendons in man. Brain. 1983;106:21–37. doi: 10.1093/brain/106.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsom Davis J. The response to stretch of human intercostal muscle spindles studied in vitro. J Physiol. 1975;249:561–579. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp011030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proske U, Morgan DL, Gregory JE. Muscle history dependence of responses to stretch of primary and secondary endings of cat soleus muscle spindles. J Physiol. 1992;445:81–95. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp018913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refshauge KM, Chan R, Taylor JL, McCloskey DI. Detection of movements imposed on human hip, knee, ankle and toe joints. J Physiol. 1995;488:231–241. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refshauge KM, Fitzpatrick RC. Perception of movement at the human ankle: effects of leg position. J Physiol. 1995;488:243–248. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refshauge KM, Taylor JL, McCloskey DI, Gianoutsos M, Mathews P, Fitzpatrick RC. Movement detection at the human big toe. J Physiol. 1998;513:307–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.307by.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL, McCloskey DI. Ability to detect angular displacements of the fingers made at an imperceptibly slow speed. Brain. 1990;113:157–166. doi: 10.1093/brain/113.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL, McCloskey DI. Detection of slow movements imposed at the elbow during active flexion in man. J Physiol. 1992;457:503–513. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallbo AB, Hagbarth KE, Torebjork HE, Wallin BG. Somatosensory, proprioceptive, and sympathetic activity in human peripheral nerves. Physiol Rev. 1979;59:919–957. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.4.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verschueren SM, Cordo PJ, Swinnen SP. Representation of wrist joint kinematics by the ensemble of muscle spindles from synergistic muscles. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:2265–2276. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.5.2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson LR, Gandevia SC, Burke D. Increased resting discharge of human spindle afferents following voluntary contractions. J Physiol. 1995;488:833–840. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter JA, Allen TJ, Proske U. Muscle spindle signals combine with the sense of effort to indicate limb position. J Physiol. 2005;568:1035–1046. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.092619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise AK, Gregory JE, Proske U. The effects of muscle conditioning on movement detection thresholds at the human forearm. Brain Res. 1996;735:125–130. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00603-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise AK, Gregory JE, Proske U. Detection of movements of the human forearm during and after co-contractions of muscles acting at the elbow joint. J Physiol. 1998;508:325–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.325br.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worringham CJ, Stelmach GE. The contribution of gravitational torques to limb position sense. Exp Brain Res. 1985;61:38–42. doi: 10.1007/BF00235618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]