Abstract

The release of neurotransmitter via exocytosis is a highly conserved, fundamental feature of nervous system function. At conventional synapses, neurotransmitter release occurs as a brief burst of exocytosis triggered by an action potential. By contrast, at the first synapse of the vertebrate visual pathway, not only is the calcium-dependent release of neurotransmitter typically graded with respect to the presynaptic membrane potential, but release can be maintained throughout the duration of a sustained stimulus. The specializations that provide for graded and sustained release are not well-defined. However, recent advances in our understanding of basic synaptic vesicle dynamics and the calcium sensitivity of the release process at these and other central, glutamatergic neurons have shed some light on the photoreceptor's extraordinary abilities.

The vertebrate photoreceptor is a primary sensory neuron that transmits information in a manner that is graded with respect to presynaptic membrane potential. This highly unusual feature allows small changes, such as the 1 mV drop in membrane potential caused by the absorption of a single photon, to be relayed to second-order neurons and ultimately perceived. In addition, these remarkable neurons have the ability to release neurotransmitter continuously in a stimulus- and calcium-dependent manner. For example, at the dark resting membrane potential, a photoreceptor releases the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate at a rate of 20–80 vesicles per active zone per second (reviewed in Heidelberger et al. 2005). If maintained at this rate, then during the course of a 10 h period of darkness (e.g. at night), each active zone of a photoreceptor would release as many as several million vesicles! How is such a prodigious output maintained? How do synaptic vesicle dynamics support continuous release? What mechanisms underlie graded release? Recent biophysical studies of photoreceptor exocytosis and synaptic vesicle dynamics provide some clues.

Mechanisms contributing to sustained release

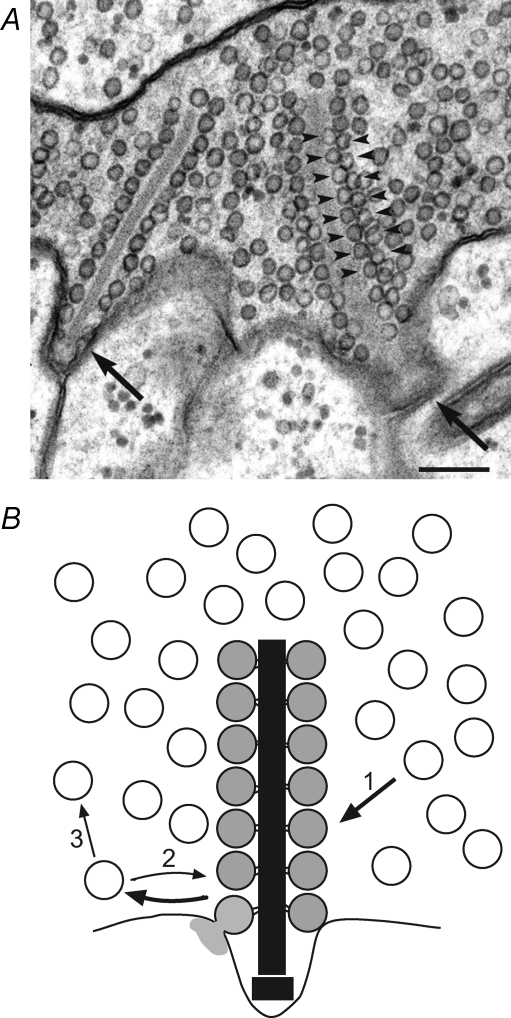

At the ultrastructural level, the active zones of photoreceptors are distinct from those of the typical conventional synapse. Rather than having a loose cluster of 10–100 vesicles at the presynaptic active zone, photoreceptor active zones are marked by the presence of a synaptic ribbon to which a large array of synaptic vesicles are tethered (Fig. 1). For the salamander rod photoreceptor, the number of tethered vesicles may exceed 700 vesicles per active zone (Thoreson et al. 2004), while for the cone, the number may be closer to 100 (Sterling & Matthews, 2005). That the ribbon-associated vesicle population is important for function is shown by: (1) the proper placement of the synaptic ribbons at the plasma membrane is essential for appropriately timed and sized exocytosis (Allwardt et al. 2001; Dick et al. 2003; Van Epps et al. 2004; Khimich et al. 2005), (2) exocytosis occurs preferentially at these cites (Zenisek et al. 2003), and (3) ribbon-associated vesicles fuse during exocytosis (Lenzi et al. 2002). Whether release may additionally occur at extra-ribbon sites remains a matter of debate.

Figure 1. The rod photoreceptor ribbon synapse.

A, electron micrograph of a salamander rod photoreceptor terminal showing two synaptic ribbons (arrows) lined by synaptic vesicles. Numerous vesicles are also present throughout the cytosol. Scale bar, 200 nm. Reproduced with permission from Thoreson et al. (2004), copyright Elsevier. B, schematic diagram of ribbon-style active zone showing ribbon-tethered vesicles and cytoplasmic vesicles. The ribbon-associated, releasable pool can be replenished from the cytoplasmic pool (arrow 1). Following exocytosis (e.g. light grey vesicle at ribbon bottom left), a vesicle can be retrieved to either refill the releasable pool (arrow 2) or join the large cytoplasmic reserve (arrow 3).

Synaptic vesicles are functionally characterized as belonging to different pools depending upon their fusion kinetics, which reflect the average proximity of vesicles in the pool to calcium channels and the state of vesicle preparedness for calcium-triggered fusion. Vesicles in the releasable pool are fusion-competent, having passed through all priming steps, and are poised for fusion upon elevation of local calcium. Thoreson et al. (2004) used two stimulation protocols to physiologically probe the releasable pool in the salamander rod photoreceptor. The results revealed a releasable pool of 3500–5000 vesicles. This corresponds to 600–1000 releasable vesicles per active zone (AZ), in agreement with the number of ribbon-tethered vesicles (Thoreson et al. 2004). Physiological estimates of the salamander cone releasable pool, which has not been as rigorously examined, range from ∼1000 (B. Innocenti and R. Heidelberger, unpublished observations) to possibly a few thousand, depending upon experimental conditions (Rabl et al. 2005). Assuming approximately 10–15 ribbons per cone terminal (S. M. Wu, personal communication), this would suggest a cone releasable pool of 75–500 vesicles per AZ, with the lower estimate in keeping with anatomical data.

The number of vesicles available for release at a photoreceptor ribbon-style active zone exceeds that of a typical conventional synapse by at least an order of magnitude (Stevens & Tsujimoto, 1995; Satzler et al. 2002; Taschenberger et al. 2002; Hallermann et al. 2003; Fernandez-Alfonso & Ryan, 2006) and thus, could more easily support the sustained release of neurotransmitter. However, it is worth noting that cerebellar mossy fibres, which exhibit long periods of high-frequency spiking, employ a physiologically defined releasable pool of about 300 vesicles per AZ (Saviane & Silver, 2006). Thus, the utilization of a large releasable pool is not a feature peculiar to ribbon synapses or graded release, but represents a general strategy for maintaining release at synapses with high synaptic demand.

Even though large, the releasable pool is not infinite. To maintain a release rate of 20–80 vesicles per AZ per second during the course of a 10 h night, the releasable pool would need to be replenished about 2000 times. Ultimately, it is the interplay between the rate of pool depletion and the rate of pool refilling that determines the ability to maintain release. In both rods and cones, recovery from paired-pulse depression, used as an assay of pool depletion and replenishment, is complete within a few seconds (DeVries, 2000; Innocenti & Heidelberger, 2005; Rabl et al. 2006). The shortest estimates (τ≈ 100–300 ms) may represent replenishment of a subset of vesicles rather than the entire releasable pool (DeVries, 2000; Heidelberger & Innocenti, 2006) or perhaps calcium-accelerated refilling of the pool (von Ruden & Neher, 1993; Sakaba et al. 1997; von Gersdorff & Matthews, 1997; Gomis et al. 1999). Careful depletion of a well-defined releasable pool in cells in which calcium measurements were simultaneously performed, yielded the longer estimate (τ≈ 1 s). Although, the exact time constant of recovery is not yet clear, the range of values suggests a significantly more rapid time course than reported for other neurons, where refilling of the releasable pool typically takes 15–20 s (Stevens & Tsujimoto, 1995; von Gersdorff & Matthews, 1997; von Gersdorff et al. 1997). An exception to this generalization is the hair cell; this graded primary sensory neuron also appears to have an unusually rapid refilling rate (Edmonds et al. 2004; Spassova et al. 2004).

What is the source of new vesicles? At conventional synapses, refilling is tightly coupled to endocytosis (De Camilli et al. 1995; Shupliakov et al. 1997; Daly et al. 2000), but this is not necessarily the case at ribbon synapses, where the releasable pool can be refilled multiple times in the absence of complete membrane retrieval (Parsons et al. 1994; von Gersdorff & Matthews, 1997; Heidelberger et al. 2002; Holt et al. 2004). In photoreceptors, both early tracer studies and recent studies using FM dyes have shown that retrieved vesicles are dispersed throughout the cytosolic pool (Fig. 1B) rather than being preferentially localized to synaptic ribbons (Schacher et al. 1974; Schaeffer & Raviola, 1978; Townes-Anderson et al. 1985; Rea et al. 2004). In addition, photoreceptor membrane retrieval may begin following a delay of half a second or more (Rieke & Schwartz, 1996) and can take a second, if not tens of seconds, to reach completion depending upon experimental conditions (Rabl et al. 2005; B. Innocenti and R. Heidelberger, unpublished observations), similar to other neurons. Thus, it seems unlikely that refilling from newly retrieved vesicles can be the sole mechanism by which the photoreceptor releasable pool is maintained. To avoid an empty fusion site that would erroneously signal an increase in illumination, replenishment of the releasable pool from the large cytoplasmic reserve (Fig. 1) emerges as an attractive alternative. Reserve vesicles in photoreceptors are significantly more mobile than those of conventional synapses, suggestive of the potential to rapidly refill an empty vesicle docking site (Rea et al. 2004; see also discussion in Heidelberger & Innocenti, 2006). A question for the future is whether all vesicles in the cytoplasmic pool are equally able to replenish the releasable pool or whether there is heterogeneity within this large pool.

Mechanisms contributing to graded release

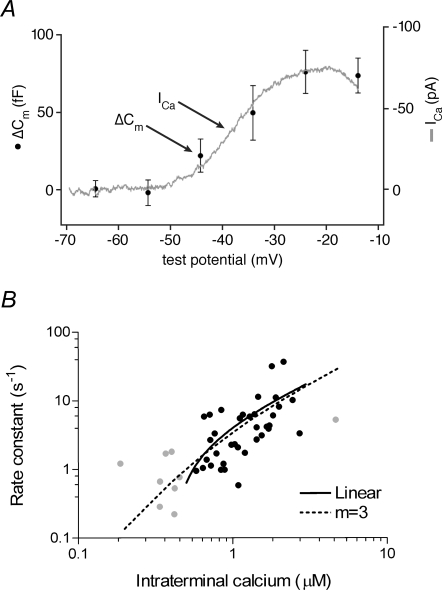

From invertebrates to mammals, the typical relationship between neuronal exocytosis and calcium current is supralinear, resulting in a rapid, synchronized burst of neurotransmitter release in response to a calcium stimulus that reaches the threshold for exocytosis. By contrast, one of the striking features of synaptic transmission at the photoreceptor synapse is the remarkable ability to relay detailed and temporally precise information about stimulus-evoked, graded changes in presynaptic membrane potential. This interesting property arises because over much of the physiologically relevant range of rod and cone membrane voltage, the relationship between voltage, calcium current and the extent of exocytosis is nearly linear (Fig. 2A; Thoreson et al. 2004; Rabl et al. 2006). Linearity between exocytosis and calcium entry has also been reported at a few other primary sensory neurons, in addition to endocrine cells and retinal amacrine cells (reviewed in Heidelberger & Innocenti, 2006).

Figure 2. The relationship between release and calcium is nearly linear.

A, capacitance measurements were used to monitor the magnitude of exocytosis in isolated salamander rods evoked by 100 ms depolarizing voltage steps to various test potentials (•). The voltage dependence of the magnitude of exocytosis mirrors that of ICa (grey curve). Reproduced with permission from Thoreson et al. (2004), copyright Elsevier. B, the relationship between the rate of exocytosis and local calcium is unusually shallow in rods. The dotted line represents a model simulation that presupposes that release occurs only from the fully bound state of a calcium sensor with three identical calcium binding sites. In the presumed physiological range (black data points), the relationship between fusion rate and calcium can be approximated by a line (black curve). Note that release can be triggered by submicromolar calcium. Reproduced with permission from Thoreson et al. (2004), copyright Elsevier.

What specializations provide for the unusual linear relationship between exocytosis and calcium entry? One mechanism is intrinsic to the secretory apparatus. The rod photoreceptor exhibits a relationship between the rate of fusion and local calcium that is relatively shallow. Mathematical modelling suggests that calcium sensor(s) for exocytosis in the rod requires no more than three calcium binding sites be occupied in order to trigger fusion (Fig. 2B). This stands in contrast to other synapses, where dependence of the rate of exocytosis on local calcium is at least fourth- or fifth-order (Heidelberger et al. 1994; Bollmann et al. 2000; Schneggenburger & Neher, 2000; Beutner et al. 2001). Perhaps more importantly, within the limited range of calcium concentrations believed to represent the normal operating range in the absence of a supersaturating stimulus (Rieke & Schwartz, 1996), the relationship between release and calcium is approximately linear (Fig. 2B). Thus, it is the combination of the calcium-binding properties of the sensor and the operational range of the neuron that generates the ability to release in a graded fashion.

The underlying modecular mechanism for this profound difference in functionality is not known. One possibility is that the rod uses a novel calcium sensor, as has been suggested for the cochlear hair cell (Safieddine & Wenthold, 1999; Roux et al. 2006). However, mammalian photoreceptors, and possibly those of the salamander, contain synaptotagmin I, the putative low-affinity calcium sensor for fast neurotransmitter release (reviewed in Heidelberger et al. 2005; Fox & Sanes, 2007). In addition, they may contain synaptotagmin III, which binds calcium with an affinity that is better matched to the high calcium sensitivity of the rod sensor (Fig. 2B). Possibly, these proteins work together and with additional proteins to refine the calcium sensitivity of exocytosis. However, this would not necessarily account for the relatively shallow relationship that generates the linearity (Goda & Stevens, 1994).

An interesting explanation for linearity at the level of the secretory machinery is suggested by recent work in the calyx of Held, where an allosteric model was found to describe the relationship between release rate and calcium better than traditional models (Lou et al. 2005). With the allosteric model, release not only occurs from the fully occupied state of the calcium sensor, as in traditional models, but from all states, albeit at slower rates. An attractive feature of this modification is that the relationship between the rate of release and calcium reflects the number of occupied calcium binding sites. Thus, any neuron might release in a graded manner if the local calcium concentration were sufficiently low relative to the affinity for calcium of the binding sites. Given that rod exocytosis is exquisitely sensitive to small increases in calcium (Fig. 2B), this hypothesis is quite attractive. The model relationship grows steeper as more binding sites on the sensor become occupied, predicting that even a photoreceptor might release a burst of neurotransmitter given the right stimulus, and there are hints that this may indeed happen (Kreft et al. 2003; Xu et al. 2005). Honing in on whether such a single-sensor model could quantitatively account for all the features of release at the rod photoreceptor is one of the challenges for the future.

Concluding remarks

Vertebrate photoreceptors are central, glutamatergic neurons specialized for the transmission of analog signals. Understanding how they function is critical to understanding the way in which we perceive the visual world. It is also necessary for understanding the many blinding disorders that affect humans worldwide. Although the fundamental features of calcium-dependent exocytosis are highly conserved, the mechanisms have been adapted in photoreceptors to give rise to their extraordinary ability to relay information about light intensity in a tonic and graded manner. Delineation of the molecular basis for these adaptations will contribute not only to the understanding of photoreceptor physiology, but provide general insights applicable to all neurons about the regulation of synaptic vesicle dynamics and the secretory cycle.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Drs Wallace Thoreson and Barbara Innocenti for stimulating discussions and gratefully acknowledges the support of the National Eye Institute (EY-12128).

References

- Allwardt BA, Lall AB, Brockerhoff SE, Dowling JE. Synapse formation is arrested in retinal photoreceptors of the zebrafish nrc mutant. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2330–2342. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-07-02330.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutner D, Voets T, Neher E, Moser T. Calcium dependence of exocytosis and endocytosis at the cochlear inner hair cell afferent synapse. Neuron. 2001;29:681–690. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollmann JH, Sakmann B, Borst JG. Calcium sensitivity of glutamate release in a calyx-type terminal. Science. 2000;289:953–957. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly C, Sugimori M, Moreira JE, Ziff EB, Llinas R. Synaptophysin regulates clathrin-independent endocytosis of synaptic vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6120–6125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.6120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Camilli P, Takei K, McPherson PS. The function of dynamin in endocytosis. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1995;5:559–565. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(95)80059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries SH. Bipolar cells use kainate and AMPA receptors to filter visual information into separate channels. Neuron. 2000;28:847–856. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00158-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick O, tom Dieck S, Altrock WD, Ammermuller J, Weiler R, Garner CC, Gundelfinger ED, Brandstatter JH. The presynaptic active zone protein bassoon is essential for photoreceptor ribbon synapse formation in the retina. Neuron. 2003;37:775–786. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds BW, Gregory FD, Schweizer FE. Evidence that fast exocytosis can be predominantly mediated by vesicles not docked at active zones in frog saccular hair cells. J Physiol. 2004;560:439–450. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.066035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Alfonso TR, Ryan TA. The efficiency of the synaptic vesicle cycle at central nervous system synapses. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:413–420. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MA, Sanes JR. Synaptotagmin I and II are present in distinct subsets of central synapses. J Comp Neurol. 2007;503:280–296. doi: 10.1002/cne.21381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goda Y, Stevens CF. Two components of transmitter release at a central synapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:12942–12946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomis A, Burrone J, Lagnado L. Two actions of calcium regulate the supply of releasable vesicles at the ribbon synapse of retinal bipolar cells. J Neurosci. 1999;19:6309–6317. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-15-06309.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallermann S, Pawlu C, Jonas P, Heckmann M. A large pool of releasable vesicles in a cortical glutamatergic synapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8975–8980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432836100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidelberger R, Heinemann C, Neher E, Matthews G. Calcium dependence of the rate of exocytosis in a synaptic terminal. Nature. 1994;371:513–515. doi: 10.1038/371513a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidelberger R, Innocenti B. Neurotransmitter release at a tonic synapse: how ordinary mechanisms accomplish an extraordinary task. Cellscience Rev. 2006;3:151–183. [Google Scholar]

- Heidelberger R, Thoreson WB, Witkovsky P. Synaptic transmission at retinal ribbon synapses. Prog Retinal Eye Res. 2005;24:682–720. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidelberger R, Zhou ZY, Matthews G. Multiple components of membrane retrieval in synaptic terminals revealed by changes in hydrostatic pressure. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:2509–2517. doi: 10.1152/jn.00267.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt M, Cooke A, Neef A, Lagnado L. High mobility of vesicles supports continuous exocytosis at a ribbon synapse. Curr Biol. 2004;14:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti R, Heidelberger R. Neurotransmitter release in cone photoreceptors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4533. E-Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Khimich D, Nouvian R, Pujol R, Tom Dieck S, Egner A, Gundelfinger ED, Moser T. Hair cell synaptic ribbons are essential for synchronous auditory signalling. Nature. 2005;434:889–894. doi: 10.1038/nature03418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreft M, Krizaj KD, Grilc S, Zorec R. Properties of exocytotic response in vertebrate photoreceptors. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:218–225. doi: 10.1152/jn.01025.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzi D, Crum J, Ellisman MH, Roberts WM. Depolarization redistributes synaptic membrane and creates a gradient of vesicles on the synaptic body at a ribbon synapse. Neuron. 2002;36:649–659. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou X, Scheuss V, Schneggenburger R. Allosteric modulation of the presynaptic Ca2+ sensor for vesicle fusion. Nature. 2005;435:497–501. doi: 10.1038/nature03568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons TD, Lenzi D, Almers W, Roberts WM. Calcium-triggered exocytosis and endocytosis in an isolated presynaptic cell: capacitance measurements in saccular hair cells. Neuron. 1994;13:875–883. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabl K, Cadetti L, Thoreson WB. Kinetics of exocytosis is faster in cones than in rods. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4633–4640. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4298-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabl K, Cadetti L, Thoreson WB. Paired-pulse depression at photoreceptor synapses. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2555–2563. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3667-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rea R, Li J, Dharia A, Levitan ES, Sterling P, Kramer RH. Streamlined synaptic vesicle cycle in cone photoreceptor terminals. Neuron. 2004;41:755–766. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieke F, Schwartz EA. Asynchronous transmitter release: control of exocytosis and endocytosis at the salamander rod synapse. J Physiol. 1996;493:1–8. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux I, Safieddine S, Nouvian R, Grati M, Simmler MC, Bahloul A, Perfettini I, Le Gall M, Rostaing P, Hamard G, Triller A, Avan P, Moser T, Petit C. Otoferlin, defective in a human deafness form, is essential for exocytosis at the auditory ribbon synapse. Cell. 2006;127:277–289. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safieddine S, Wenthold RJ. SNARE complex at the ribbon synapses of cochlear hair cells: analysis of synaptic vesicle- and synaptic membrane-associated proteins. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:803–812. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaba T, Tachibana M, Matsui K, Minami N. Two components of transmitter release in retinal bipolar cells: exocytosis and mobilization of synaptic vesicles. Neurosci Res. 1997;27:357–370. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(97)01168-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satzler K, Sohl LF, Bollmann JH, Borst JG, Frotscher M, Sakmann B, Lubke JH. Three-dimensional reconstruction of a calyx of Held and its postsynaptic principal neuron in the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10567–10579. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10567.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saviane C, Silver RA. Fast vesicle reloading and a large pool sustain high bandwidth transmission at a central synapse. Nature. 2006;439:983–987. doi: 10.1038/nature04509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacher SM, Holtzman E, Hood DC. Uptake of horseradish peroxidase by frog photoreceptor synapses in the dark and the light. Nature. 1974;249:261–263. doi: 10.1038/249261a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer SF, Raviola E. Membrane recycling in the cone cell endings of the turtle retina. J Cell Biol. 1978;79:802–825. doi: 10.1083/jcb.79.3.802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneggenburger R, Neher E. Intracellular calcium dependence of transmitter release rates at a fast central synapse. Nature. 2000;406:889–893. doi: 10.1038/35022702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shupliakov O, Low P, Grabs D, Gad H, Chen H, David C, Takei K, De Camilli P, Brodin L. Synaptic vesicle endocytosis impaired by disruption of dynamin–SH3 domain interactions. Science. 1997;276:259–263. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5310.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spassova MA, Avissar M, Furman AC, Crumling MA, Saunders JC, Parsons TD. Evidence that rapid vesicle replenishment of the synaptic ribbon mediates recovery from short-term adaptation at the hair cell afferent synapse. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2004;5:376–390. doi: 10.1007/s10162-004-5003-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling P, Matthews G. Structure and function of ribbon synapses. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens CF, Tsujimoto T. Estimates for the pool size of releasable quanta at a single central synapse and for the time required to refill the pool. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:846–849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taschenberger H, Leao RM, Rowland KC, Spirou GA, von Gersdorff H. Optimizing synaptic architecture and efficiency for high-frequency transmission. Neuron. 2002;36:1127–1143. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoreson WB, Rabl K, Townes-Anderson E, Heidelberger R. A highly Ca2+-sensitive pool of vesicles contributes to linearity at the rod photoreceptor ribbon synapse. Neuron. 2004;42:595–605. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00254-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townes-Anderson E, MacLeish PR, Raviola E. Rod cells dissociated from mature salamander retina: ultrastructure and uptake of horseradish peroxidase. J Cell Biol. 1985;100:175–188. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.1.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Epps HA, Hayashi M, Lucast L, Stearns GW, Hurley JB, De Camilli P, Brockerhoff SE. The zebrafish nrc mutant reveals a role for the polyphosphoinositide phosphatase synaptojanin 1 in cone photoreceptor ribbon anchoring. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8641–8650. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2892-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Gersdorff H, Matthews G. Depletion and replenishment of vesicle pools at a ribbon-type synaptic terminal. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1919–1927. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-06-01919.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Gersdorff H, Schneggenburger R, Weis S, Neher E. Presynaptic depression at a calyx synapse: the small contribution of metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Neurosci. 1997;17:8137–8146. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08137.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Ruden L, Neher E. A Ca-dependent early step in the release of catecholamines from adrenal chromaffin cells. Science. 1993;262:1061–1065. doi: 10.1126/science.8235626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu JW, Hou M, Slaughter MM. Photoreceptor encoding of supersaturating light stimuli in salamander retina. J Physiol. 2005;569:575–585. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.092239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenisek D, Davila V, Wan L, Almers W. Imaging calcium entry sites and ribbon structures in two presynaptic cells. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2538–2548. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02538.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]