Abstract

Information processing in neuronal networks is determined by the use-dependent dynamics of synaptic transmission. Here we characterize the dynamic properties of excitatory synaptic transmission in two major intracortical pathways that target the output neurons of the neocortex, by recording unitary EPSPs from layer 5 pyramidal neurons evoked in response to action potential trains of increasing complexity in presynaptic layer 2/3 or layer 5 pyramidal neurons. We find that layer 2/3 to layer 5 synaptic transmission is dominated by frequency-dependent depression when generated at fixed frequencies of > 10 Hz. Synaptic depression evolved on a spike-by-spike basis in response to action potential trains that possessed a broad range of interspike intervals, but a low mean frequency (10 Hz). Layer 2/3 to layer 2/3 and layer 2/3 to layer 5 synapses were incapable of sustained release during prolonged, complex trains of presynaptic action potential firing (mean frequency, 48 Hz). By contrast, layer 5 to layer 5 synapses operated effectively across a wide range of frequencies, exhibiting increased efficacy at frequencies > 10 Hz. Furthermore, layer 5 to layer 5 synapses sustained release throughout the duration of prolonged, complex spike trains. The use-dependent properties of synaptic transmission could be modulated by pharmacologically changing the probability of release and by induction of long-term depression. The dynamic properties of intracortical excitatory synapses are therefore pathway-specific. We suggest that the synaptic output of layer 5 pyramidal neurons is ideally suited to control the neocortical network across a wide range of frequencies and for sustained periods of time, a behaviour that helps to explain the pivotal role played by layer 5 neurons in the genesis of periods of network ‘up’ states and epileptiform activity in the neocortex.

The basic wiring diagram of the neocortical microcircuit has been described, charting the flow of information in sensory cortices from thalamic recipient layers, primarily layer 4, through intracortical circuits of layers 2 and 3 to the output neurons of the neocortex layer 5 pyramidal neurons (Gilbert, 1983; Douglas & Martin, 2004). Recently, single- and multineuron recording techniques have allowed analysis of the functional properties of excitatory synaptic transmission between neocortical neurons in vitro, revealing that dense intra- and interlaminar excitatory synaptic connections onto pyramidal neurons display prominent use-dependent depression at low frequencies of activation (typically < 20 Hz) (Thomson et al. 1993; Abbott et al. 1997; Markram et al. 1997; Varela et al. 1997; Galarreta & Hestrin, 1998; Thomson & Bannister, 1998; Silver et al. 2003), while inputs to inhibitory neurons can display use-dependent facilitation (Markram et al. 1998; Reyes et al. 1998). Synaptic depression has been suggested to allow the dynamic adjustment of intracortical excitatory synaptic efficacy according to the rate of presynaptic action potential firing, functioning as a form of gain control that prevents saturation during high-frequency activation (Abbott et al. 1997), but permits the faithful transmission of low-frequency rate codes (Fuhrmann et al. 2002). In vivo, however, neocortical neurons can fire action potentials at high frequencies (50–200 Hz) for sustained periods of time, if driven by optimal sensory stimuli (Hubel & Wiesel, 1959; Buracas et al. 1998; deCharms et al. 1998; Shadlen & Newsome, 1998) or examined under behaviourally relevant conditions in awake animals (Porter et al. 1971; Steriade et al. 2001; Krupa et al. 2004; Chen & Fetz, 2005; Luna et al. 2005). Furthermore, neocortical neurons exhibit prominent subthreshold synaptic activity and ongoing patterns of action potential firing generated, intrinsically, by intracortical excitatory circuits (Sanchez-Vives & McCormick, 2000; Ikegaya et al. 2004), which can determine the output of neurons in response to natural stimuli in vivo (Arieli et al. 1996).

Has the degree of synaptic depression in intracortical excitatory pathways therefore been overestimated by in vitro studies? In support of this idea, the use-dependent properties of intracortical excitatory transmission are developmentally regulated, favouring higher frequencies of activation in older animals (Bolshakov & Siegelbaum, 1995; Angulo et al. 1999; Reyes & Sakmann, 1999). This finding is partially explicable by a developmental switch in the composition of synaptic AMPA receptors (Shin et al. 2005). Furthermore, the degree of synaptic depression is reduced in other central excitatory synapses when studied at near physiological temperatures (Pyott & Rosenmund, 2002; Fernandez-Alfonso & Ryan, 2004; Klyachko & Stevens, 2006; Kushmerick et al. 2006). Here we investigate the dynamics of transmission in two major intracortical pathways, by examining excitatory transmission between synaptically connected pairs of pyramidal neurons in brain slices, obtained from rats at postnatal day (P) 25–36 maintained at near physiological temperatures.

Methods

Recordings were made from neocortical pyramidal neurons in brain slices (300 μm) prepared from Wistar rats (P25 to P36) following institutional and UK Home Office guidelines. Rats were anaesthetized by the inhalation of isoflurane and decapitated. Brain slices were perfused with a solution of composition (mm): NaCl 125, NaHCO3 25, KCl 3, NaH2PO4 1.25, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 1, sodium pyruvate 3 and glucose 25 at 35–37°C. Triple and quadruple whole-cell recordings were made with identical current-clamp amplifiers (BVC 700A; Dagan, Minneapolis, MN, USA). In the majority of experiments, pipettes were filled with a solution containing (mm): potassium gluconate 135, NaCl 7, Hepes 10, Na2-ATP 2, Na-GTP 0.3, MgCl2 2 and Alexa Fluor 568 0.01 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA); pH was adjusted to 7.2–7.3 with KOH. When calcium chelators (ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA) or 1,2-bis(O-aminophenoxy)-ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA)) were included in the intrapipette solution, the concentration of potassium gluconate was proportionally reduced; in these experiments l-glutamate (5 mm) was included in control and chelator-containing solutions to control for the possibility that synaptic depression was mediated by the insufficiency of free glutamate (Ishikawa et al. 2002). When calcium chelators were used, an initial recording period of > 20 min was allowed for axonal diffusion of the chelator; subsequently our test protocol took > 40 min to complete. For plasticity experiments, pipettes were filled with a solution containing (mm): potassium gluconate 120, KCl 20, Hepes 10, Mg-ATP 4, Na-GTP 0.3, sodium phosphocreatine 10 and Alexa Fluor 568 0.01; pH was adjusted to 7.3–7.4 with KOH. Pipettes used for somatic recordings had resistance of between 3 and 6 MΩ and pipettes for apical dendritic recordings 10 to 12 MΩ. At the termination of each experiment, the location and morphology of neurons was examined by fluorescence microscopy and digitally recorded (Retiga EXI, QImaging, Burnaby, BC, Canada). Higher resolution images were obtained by the reconstruction of the morphology of Alexa Fluor 568-filled neurons after unfixed brain slices were mounted in vector shield mounting reagent (Vector, Burlingame, CA, USA). Neuronal morphology was revealed in grey scale projections of 1 μm confocal optical sections (10–30 sections, Bio-Rad Radiance 2000; Fig. 4B).

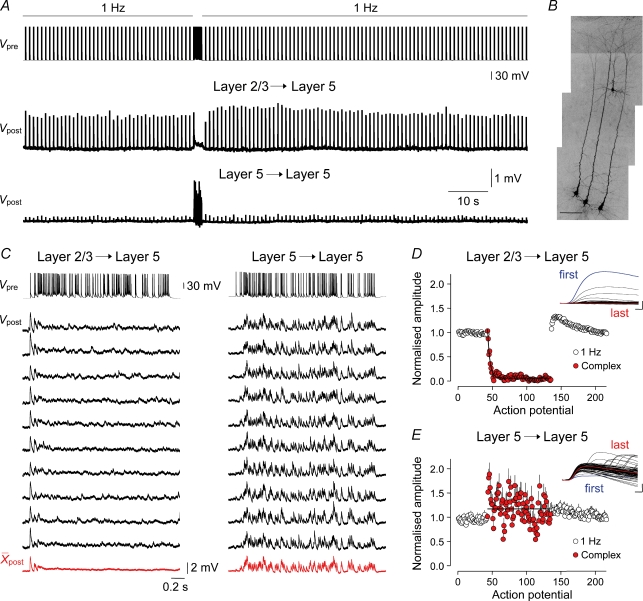

Figure 4. Sustained transmission at intracortical synapses.

A, the upper continuous presynaptic voltage record (Vpre) illustrates the experimental protocol, showing transition from a low frequency (1 Hz) to a complex pattern of action potential firing. The lower traces show continuous postsynaptic voltage responses (Vpost) recorded from the soma of layer 5 pyramidal neurons. Each vertical deflection represents an averaged unitary EPSP. B, the morphology of neurons is shown in a grey scale projection of thirty 1 μm optical sections; the scale bar represents 100 μm. C, layer 2/3 to layer 5 unitary EPSPs depress strongly and rapidly at the onset of the complex spike train (left), whereas unitary layer 5 to layer 5 EPSPs are generated in response to each action potential of the complex spike train. Black traces represent single trials and red traces are digital averages. D, layer 2/3 to layer 5 unitary EPSPs depress over the first few action potentials of the complex spike train to reach a steady state (red). The line is a mono-exponential fit to pooled data with a τ of 3.4 action potentials (n = 28 connections). Unitary EPSP amplitude has been normalized to the first 10 responses evoked at 1 Hz in each connection. E, facilitation of layer 5 to layer 5 synaptic transmission during the complex spike train (red). The line represents the average amplitude throughout the complex spike train, n = 18 connections. The insets in D and E show overlain unitary EPSPs evoked during the complex train in a layer 2/3 to layer 5 and layer 5 to layer 5 connection, respectively; scale bars, 0.5 mV and 1 ms, respectively.

Synaptic connectivity

Excitatory synaptic transmission was examined between groups of simultaneously recorded pyramidal neurons in the parietal association and the primary and secondary somatosensory cortices. Neurons were identified by their characteristic morphology under infrared differential interference contrast (IR-DIC) microscopy. All recordings from layer 5 were restricted to large pyramidal neurons that had thick apical dendrites ending in a tuft in layer 1 when visualized under IR-DIC or fluorescent microscopy and exhibited either regular or burst action potential firing patterns (Williams & Stuart, 1999) and so were likely to correspond to sublamina layer 5B. Synaptic connectivity between large layer 5 pyramidal neurons was investigated by recording groups (usually three or four) of closely spaced (< 100 μm soma to soma separation) neurons. When searching for layer 2/3 to layer 5 synaptic connectivity, we recorded groups (usually three) of large layer 5 pyramidal neurons and searched for a synaptically connected layer 2/3 pyramidal neuron. Layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons were identified visually under IR-DIC; the somata of synaptically connected layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons were invariably located close (< 100 μm) to the apical dendrite of the postsynaptic large layer 5 pyramidal neuron (Fig. 4B). In each case synaptic connectivity was tested for by the repeated generation of a pair of action potentials (2 ms test pulses; 1–5 nA; separated by 25 ms; delivered at 0.33 Hz). If no connectivity was found, one of the recording electrodes was withdrawn and a new pyramidal neuron recorded.

When complex patterns of action potential firing were generated, each presynaptic action potential was evoked by the delivery of a 20 μs current pulse of 50–100 nA that evoked action potential firing with high temporal precision from trial to trial. This enabled the accurate averaging of evoked postsynaptic potentials (see Supplementary Fig. 1). A train of action potentials previously recorded extracellularly from a neuron in area MT in an awake monkey, that was evoked by optimal contrast visual stimuli, was obtained from published data (see Williams & Stuart, 2000). The absolute time of each action potential of a train was taken and a replica train of 20 μs current pulses produced. Trains of action potentials generated at fixed or variable frequencies were generated in the same manner. Voltage and current signals were filtered at 10 kHz, acquired at 50 kHz using an ITC-18 interface (Instrutech Corporation, NY, USA) controlled by an Apple computer and recorded to digital tape (DTR1802, Intracel, Royston, UK). Data were analysed and curve-fitting performed using Axograph (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA, USA). The amplitude of unitary EPSPs (uEPSPs) was measured over a 0.2 or 0.5 ms window centred around peak amplitude relative to a baseline window set 1 ms before uEPSP onset. During the course of each experiment the series resistance of the postsynaptic recording was repeatedly measured and bridge balance readjusted, but typically remained stable (< 20% change). When long-term changes of synaptic transmission were investigated, we obtained synaptically connected pairs of layer 2/3 to layer 5 pyramidal neurons within 20 min – if a unitary connection was not found after testing connectively from five presynaptic layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons all recordings were abandoned. Changes of synaptic efficacy are represented by averaging the amplitude of uEPSPs evoked at 0.2 Hz over sequential 2 min periods, before (8 min) and after a pairing protocol (260 action potentials delivered at 1 Hz, presynaptic action potential firing either led or lagged post synaptic action potential firing by 10 ms, each pre- and postsynaptic action potential was generated by a short current pulse of 20 μs or 3 ms, respectively). Recordings were abandoned if the postsynaptic series resistance increased by > 20%. Numerical values are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. unless otherwise stated. Statistical analysis was performed with Student's t test or ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test for parametric and the Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis test for non-parametric data.

Generation of simulated postsynaptic potentials

Simulated EPSPs were generated as a conductance change as previously described (Williams, 2004, 2005). Briefly, conductance-based simulated EPSPs were generated using a real-time dynamic clamp (Harsch & Robinson, 2000) from apical dendritic sites of layer 5 pyramidal neurons, using two closely spaced (6.3 ± 0.9 μm; n = 18) electrodes for current injection and voltage recording, while a third independent electrode was used to record conductance-based EPSPs (gEPSPs) at the soma or from somatic sites by dual somatic recording. The dynamic clamp was driven with an ESPC-shaped waveform (τrise= 0.2 ms and τdecay= 2 ms; gEPSC, 3–15 nS; EEPSC, 0 mV), resulting in the generation of gEPSPs with kinetics that accurately replicated those of unitary and spontaneous EPSPs in layer 5 pyramidal neurons (Williams & Stuart, 2002).

Results

Unitary excitatory postsynaptic potentials were recorded from thick-tufted layer 5 pyramidal neurons in response to patterns of action potential firing evoked in presynaptic layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons or neighbouring layer 5 pyramidal neurons during simultaneous recording of groups of three or four neurons in neocortical rat brain slices (Fig. 4B).

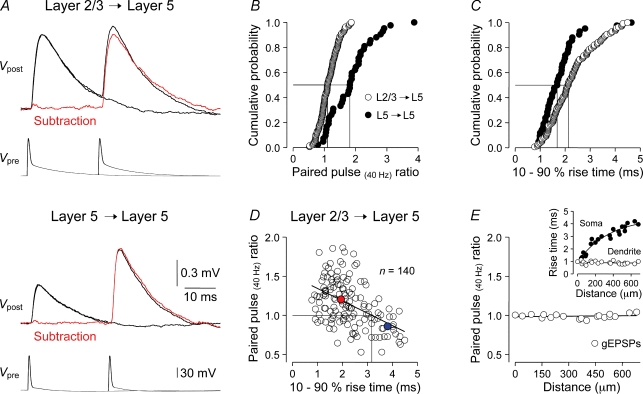

Unitary EPSPs evoked by simple spike trains

First we examined the use-dependent properties of these classes of excitatory synapse using a standard paired-pulse protocol, where two action potentials were evoked at an interval of 25 ms with a long quiescent period between presentations (5 s; Fig. 1). In response to this simple stimulus protocol, the use-dependent properties of layer 2/3 to layer 5 and layer 5 to layer 5 uEPSPs were found to be distinct. Layer 2/3 to layer 5 connections exhibited, on average, little use-dependent modification in response to the presentation of two action potentials (paired-pulse ratio, 1.14 ± 0.03; n = 140 connections), while layer 5 to layer 5 connections displayed powerful paired-pulse facilitation (1.84 ± 0.11; n = 42; P < 0.0001; Fig. 1A and B). As previous observations have suggested that the use-dependent properties of excitatory synaptic inputs are determined by the location of synapses within the dendritic tree of layer 5 pyramidal neurons (Williams & Stuart, 2002), we explored the relationship between the rise time and paired-pulse dynamics of uEPSPs. The somatic rise time of layer 5 to layer 5 uEPSPs was significantly faster than the rise time evoked by layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons (layer 5 to layer 5, 1.8 ± 0.1 ms; n = 42; layer 2/3 to layer 5, 2.3 ± 0.1 ms; n = 140; P < 0.0001). This suggests that synaptic contacts underlying layer 5 to layer 5 uEPSPs are formed at relatively proximal dendritic sites (Markram et al. 1997) and that uEPSPs generated from proximal dendritic loci exhibit a greater degree of paired-pulse facilitation (Fig. 1C). To examine whether this relationship held for a defined excitatory pathway, we plotted the relationship between the rise time and use-dependent dynamics of layer 2/3 to layer 5 uEPSPs (Fig. 1D), as layer 2/3 to layer 5 synaptic contacts have been demonstrated to be made at sites throughout the apical dendritic arbor of large layer 5 pyramidal neurons (Williams & Stuart, 2002; Sjostrom & Hausser, 2006). Pooled data revealed that fast rising layer 2/3 to layer 5 uEPSPs exhibited paired-pulse facilitation, while slow rising uEPSPs showed paired-pulse depression (r2= 0.23; uncorrelated probability, P < 0.0001; n = 140; Fig. 1D). In this pathway, therefore, a simple relationship exists between dendritic synapse location and the sign (facilitation or depression) of paired-pulse dynamics. By contrast, we found no correlation between paired-pulse ratio and uEPSP rise time for layer 5 to layer 5 uEPSPs (r2= 0.02; n = 42). To verify the assignment of the dendritic site of uEPSP generation by uEPSP rise time, and to exclude the involvement of non-linear dendritic mechanisms in shaping the distance-dependent dynamic properties of uEPSPs (Banitt et al. 2005), we simulated gEPSPs with uniform properties at defined somatodendritic sites using dendritic recording and dynamic clamp techniques. Dendritically generated gEPSPs had somatic rise times that spanned the range observed for uEPSPs (40–680 μm from the soma; Fig. 1E, inset). In contrast to uEPSPs, the paired-pulse ratio of gEPSPs recorded both at the site of generation and the soma were close to one for events generated throughout the apical dendritic tree (two gEPSCs generated at 25 ms interval; Fig. 1E). These data reveal that the dynamic properties of dendritic excitatory synapses can be recorded from the soma without distortion.

Figure 1. Paired-pulse dynamics of intracortical excitatory synapses.

A, averaged layer 2/3 to layer 5 and layer 5 to layer 5 unitary EPSPs (Vpost, upper traces) evoked in response to one and two (25 ms apart) presynaptic action potentials (Vpre). The red traces are digital subtractions. B, distribution of the paired-pulse ratios of layer 2/3 to layer 5 (^; n = 140) and layer 5 to layer 5 (•; n = 42) unitary EPSPs; the drop lines indicate median values. C, distribution of the somatic rise time of layer 2/3 to layer 5 (^) and layer 5 to layer 5 (•) unitary EPSPs; the drop lines indicate the greater median rise time of layer 2/3 to layer 5 uEPSPs. D, relationship between layer 2/3 to layer 5 unitary EPSP rise time and paired-pulse dynamics. The line represents a linear regression (r2= 0.23, n = 140), and indicates the transformation from paired-pulse facilitation to depression as rise time increases (drop lines indicate a unity point of 3.14 ms), and coloured symbols show the average paired-pulse ratio of uEPSPs with rise times faster (red) or slower (blue) than 3.14 ms. E, the paired-pulse ratio of somatically recorded conductance-based simulated EPSPs (gEPSPs) generated at sites throughout the apical dendritic tree is close to one. The inset shows that the somatic but not local dendritic gEPSP rise time increases as events are generated from increasingly remote apical dendritic sites (lines are mono-exponential fits; n = 21).

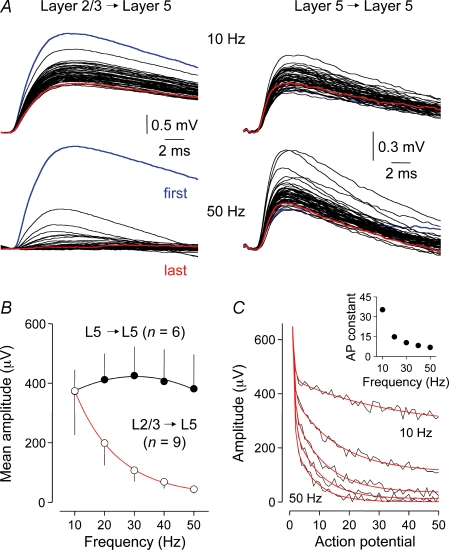

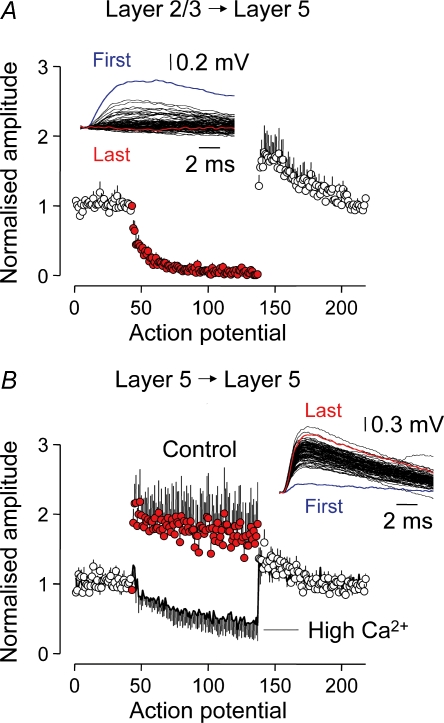

Next we explored how effectively layer 2/3 to layer 5 and layer 5 to layer 5 synapses respond to trains of presynaptic actions potentials, generated at fixed frequencies of between 10 and 50 Hz (Fig. 2). To our surprise, layer 2/3 to layer 5 uEPSPs showed pronounced frequency-dependent depression, whereas layer 5 to layer 5 uEPSPs did not exhibit depression and were generated reliably throughout trains of 50 action potentials (Fig. 2). In layer 2/3 to layer 5 connections, the magnitude of uEPSP depression increased in an exponential manner (Fig. 2A and B) and the time course of depression accelerated (Fig. 2C) as the frequency of action potential presentation was increased. Analysis revealed that at presynaptic firing frequencies above 10 Hz, layer 2/3 to layer 5 uEPSPs depressed to near steady-state after the first 10 action potentials of a train, suggesting a narrow dynamic range of operation (Fig. 2C, inset). By contrast, we found that layer 5 to layer 5 uEPSPs exhibited a broad dynamic range, responding on average with equal efficacy to trains of action potentials generated across a wide frequency range (10–50 Hz; Fig. 2A and B). Indeed, we observed that this band-pass behaviour was maintained for uEPSPs evoked throughout regular spike trains, so that the amplitudes of the last 10 uEPSPs were close to the amplitude of the first uEPSP of the train for all frequencies tested (ratio of the last 10 to the first uEPSP: 10 Hz, 1.02 ± 0.13; 20 Hz, 1.32 ± 0.26; 30 Hz, 1.36 ± 0.33; 40 Hz, 1.36 ± 0.32; 50 Hz, 1.07 ± 0.31; n = 6).

Figure 2. Frequency tuning of intracortical synapses.

A, averaged overlaid layer 2/3 to layer 5 (left) and layer 5 to layer 5 (right) unitary EPSPs evoked in response to a train of 50 action potentials delivered at the indicated frequencies. B, pathway-specific frequency-dependence of synaptic transmission. Note the strong frequency-dependent characteristics of layer 2/3 to layer 5 and the band-pass characteristics of layer 5 to layer 5 connections (mean amplitude indicates average amplitude throughout the action potential train), fitted with a single exponential and arbitrary second order polynomial function, respectively. C, frequency-dependent kinetics of layer 2/3 to layer 5 synaptic depression. Pooled data illustrate the amplitude of unitary EPSPs evoked during a 50 action potential train delivered at 10–50 Hz (10 Hz increments, average of nine connections). The red lines are bi-exponential fits to the data. The inset shows the relationship between the action potential constant (second, longer constant) of depression and firing frequency.

Unitary EPSPs evoked by complex spike trains

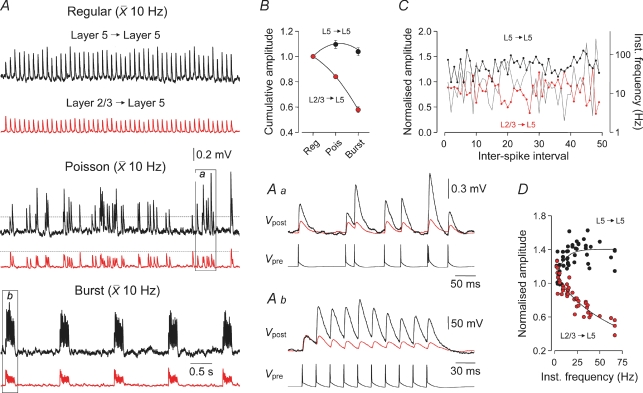

Next we examined how intracortical excitatory synapses process complex patterns of presynaptic action potential firing. Previous observations have indicated that neocortical neurons from diverse sensory cortical areas respond to optimal sensory stimuli with action potential outputs that characteristically have low mean rates (10–20 Hz), but irregular firing patterns and so have wide distributions of interspike frequencies (< 1 to > 200 Hz) (see deCharms & Zador, 2000 for a comprehensive analysis of data from various cortical regions). We therefore investigated how use-dependent properties impact on the synaptic transmission of action potential trains that possessed variable interspike intervals, but an overall low mean rate. Spike trains composed of 50 action potentials were generated either at a fixed frequency (10 Hz), with a modified Poisson distribution composed of interspike frequencies of between 2 and 250 Hz (mean, 10 Hz; median, 16.1 Hz; for instantaneous frequency distribution see Supplementary Fig. 2), or as repeated bursts of 10 action potentials generated at 50 Hz (mean, 10 Hz; median, 49.5 Hz) (Fig. 3). Layer 2/3 to layer 5 connections responded optimally to the fixed-frequency train of action potentials, but significantly less efficaciously to the Poisson train and the burst discharge pattern (cumulative uEPSP amplitude: fixed frequency, 29.3 ± 7.3 mV; Poisson, 24.6 ± 6.1 mV, P < 0.01; burst, 16.1 ± 3.3 mV, P < 0.01; n = 13; Fig. 3A and B). To explore how the use-dependent properties of layer 2/3 to layer 5 transmission controlled the amplitude of uEPSPs through the course of the Poisson spike train, we examined the relationship between instantaneous firing frequency and the amplitude of layer 2/3 to layer 5 uEPSPs, normalized to the first uEPSP of the train (pooled for 13 connections; Fig. 3C). At any point of the Poisson spike train, presynaptic firing at high instantaneous frequencies evoked depressed uEPSPs, whereas firing at low instantaneous frequencies evoked larger amplitude responses, suggesting that frequency- and use-dependent dynamics are operational throughout spike trains (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, when we plotted the amplitude of layer 2/3 to layer 5 uEPSPs as a function of instantaneous firing frequency, we found a steep frequency-dependent depression of uEPSP amplitude, indicating that layer 2/3 to layer 5 synapses behave like a low-pass filter during the course of spike trains (Fig. 3D). By contrast, layer 5 to layer 5 connections did not exhibit synaptic depression during the course of these spike trains (Fig. 3A), but transmitted the Poisson train significantly more efficaciously than the mean train (cumulative uEPSP amplitude: fixed frequency, 16.9 ± 5.4 mV; Poisson, 18.1 ± 5.6, P < 0.001; paired t test; burst, 17.4 ± 5.5 mV, P > 0.05; n = 8; Fig. 3A and B). We found that layer 5 to layer 5 connections transmitted the Poisson train effectively because synaptic transmission was facilitated at higher interspike frequencies (compare overlaid traces in Fig. 3Aa and b). This behaviour was apparent throughout the course of Poisson spike train (uEPSP amplitude normalized to the first uEPSP of the train, pooled for 8 connections; Fig. 3C and D). Therefore in contrast to the layer 2/3 to layer 5 pathway, layer 5 to layer 5 synapses behave like a high-pass filter during the course of spike trains (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3. Pathway-specific transmission of complex spike trains.

A, averaged continuous records of layer 5 to layer 5 (black) and layer 2/3 to layer 5 (red) unitary EPSPs evoked in response to spike trains of equal number, generated at identical mean rates, but with different degrees of complexity – termed regular (median, 10 Hz), Poisson (median, 16 Hz) and burst (median, 49.5 Hz). Note that in response to the Poisson train the amplitude of layer 5 to layer 5 uEPSPs increased after the first uEPSP (dashed horizontal line), whereas the amplitude of layer 2/3 to layer 5 uEPSPs decreased; this behaviour is also apparent during each burst response. Sections of these responses are shown for clarity at a faster time base (Aa and b). Note the marked facilitation of layer 5 to layer 5 uEPSPs, but depression of layer 2/3 to layer 5 uEPSPs (Vpost) when generated at high instantaneous firing frequencies (Vpre). These representative connections were chosen as the first uEPSP of each train had a similar amplitude. B, summary data showing that cumulative uEPSP amplitude decreases in response to complex spike trains (Poisson and burst trains) generated in layer 2/3 to layer 5 (n = 13), but increases in layer 5 to layer 5 connections (n = 8). C, pooled data describing the time evolution of the relationship between normalized uEPSP amplitude and instantaneous firing frequency (grey) during the Poisson spike train for layer 2/3 to layer 5 (red; n = 13) and layer 5 to layer 5 (black; n = 8) connections. Each point represents the amplitude of uEPSPs averaged across connections and plotted as a fraction of the first uEPSP of the train. D, relationship between uEPSP amplitude and action potential instantaneous frequency. Note the pronounced frequency-dependent depression in layer 2/3 to layer 5 (red), and facilitation in layer 5 to layer 5 (black) connections. Instantaneous frequencies > 75 Hz are not shown.

Sustained release during complex action potential trains

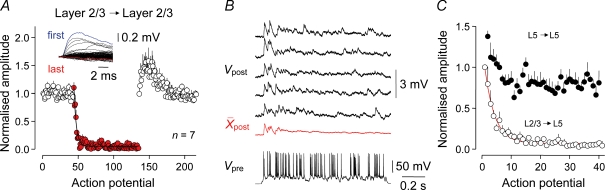

In behaving animals, neocortical pyramidal neurons are embedded in active neuronal networks that fire spontaneous and stimulus-evoked patterns of action potentials (Hubel, 1959; Porter et al. 1971; Krupa et al. 2004; Luna et al. 2005). We sought to explore how intracortical excitatory synapses sustain transmitter release under such conditions of continual use. Previous observations from immature animals have indicated that excitatory layer 2/3 to layer 5 and layer 5 to layer 5 synapses are incapable of sustained release when repeatedly activated at frequencies above 10 Hz (Galarreta & Hestrin, 1998). We therefore developed a protocol to resemble the transition from ongoing low-frequency action potential firing apparent in sensory cortices in the absence of sensory input (Hubel, 1959; Luna et al. 2005; Crochet & Petersen, 2006; de Kock et al. 2007) to a higher-frequency train of action potentials representative of an evoked sensory response. We used a previously recorded sensory response taken from a neuron in a visual cortical area of an awake monkey, which possessed a wide range of interspike frequencies and was of long duration, to test whether intracortical synapses could sustain release during the course of a prolonged and complex pattern of presynaptic action potential firing – we refer to this pattern of activity as the complex spike train (average frequency, 47.6 Hz; coefficient of variation (CV), 0.75; range of interspike frequencies, 11–245 Hz; 92 action potentials; for instantaneous frequency distribution see Supplementary Fig. 2 and Methods; Fig. 4A and C top trace). This stimulus protocol was continually repeated to investigate the dynamics of excitatory transmission under conditions of continual use over a period of between 33 and 86 min (duration of each trial, 126 s; repeated on average 28 times; range, 16–41; n = 46 unitary connections; Fig. 4).

We observed that the ability of intracortical synapses to sustain release through the course of the complex spike train was pathway-specific (Fig. 4). When uEPSPs were evoked between layer 2/3 to layer 5 pyramidal neurons, low-frequency action potential firing resulted in uEPSPs that were reliable from action potential to action potential, exhibiting only occasional failure of transmission (percentage failure rate at 1 Hz, 5.8 ± 1.8%; n = 28). By contrast, at the onset of the complex spike train, the amplitude of uEPSPs was dramatically depressed over the first few action potentials to reach a steady state of 4.4 ± 1.0% (last 40 action potentials of the complex spike train relative to 1 Hz; n = 28; Fig. 4A and C). Both the time course and magnitude of this form of use-dependent depression were consistent from trial to trial in each connection (Fig. 4C) and between unitary connections (1 Hz, 377.3 ± 40.3 μV; last 40 action potentials of complex spike train, 11.7 ± 2.4 μV; P < 0.0001; range: 79.29–99.95% reduction; n = 28; Fig. 4D, red symbols). This allowed us to fit the evolution of synaptic depression with a single exponential function with a time constant of depression, measured in number of spikes, of just 3.4 action potentials (Fig. 4D, black line). Upon termination of the complex spike train, low-frequency stimulation was reinitiated, allowing the time course of recovery from depression to be followed (Fig. 4A and D). The amplitude of uEPSPs recovered with a time constant of 0.75 s, to reach a level significantly greater than that apparent before the complex spike train (20 action potentials before, 377.3 ± 40.3 μV; 20 action potentials after, 487.5 ± 57.0 μV; 128.7 ± 4.5% augmentation; P < 0.0001; n = 28). This form of synaptic augmentation slowly decayed with an exponential time course (τ= 40.4 s). Layer 2/3 to layer 5 synaptic connections therefore do not sustain operation throughout the course of a complex spike train generated under conditions of continual use. To explore whether aspects of this behaviour resulted from the highly irregular interspike intervals during the complex spike train, instead we generated a train of action potentials evoked regularly at the same mean firing rate (Fig. 5). In common with the complex spike train, layer 2/3 to layer 5 uEPSPs showed pronounced depression in response to a regular firing pattern generated at 47.6 Hz, to reach a steady state of 5 ± 0.05% (last 40 action potentials of the spike train relative to 1 Hz; n = 5; Fig. 5A), which was followed by a period of augmented transmission at 1 Hz (162.1 ± 2.6% augmentation; n = 5). It is interesting, however, that depression evolved during the mean spike train with a time constant of 9.9 action potentials, which is slower than in response to the complex spike train. This indicates that action potential firing at high instantaneous frequency during the onset of the complex spike train rapidly engaged frequency-dependent depression of layer 2/3 to layer 5 synapses that was maintained throughout the spike train. We ruled out the possibility that these properties of synaptic depression were related to the way action potential firing was evoked during complex spike trains. Instead of evoking each spike with a short current pulse, we generated trains of action potential firing in response to an excitatory synaptic input composed of a barrage of simulated EPSCs delivered as an ideal current source to the soma of layer 2/3 or layer 5 pyramidal neurons, which drove firing reproducibly from trial to trial (Mainen & Sejnowski, 1995; Harsch & Robinson, 2000; Williams, 2005) (EPSC frequency, 500 Hz; unitary EPSC amplitude, 200 or 300 pA; τrise= 0.2 ms; τdecay= 2 ms; 31 ± 5 repetitions; for instantaneous frequency distribution see Supplementary Fig. 2; n = 5; Fig. 6B, lower traces). When challenged with this form of action potential firing pattern, layer 2/3 to layer 5 uEPSPs exhibited rapid and strong synaptic depression (average firing frequency, 57 ± 5 Hz; action potential constant of depression, 3.4; depressed to a steady-state of 5.0 ± 1.3% of initial amplitude; n = 5; Fig. 6C). By contrast, layer 5 to layer 5 synaptic connections robustly transmitted such high-frequency synthetic spike trains (average firing frequency, 49 ± 2 Hz; n = 5; Fig. 6C).

Figure 5. Sustained transmission in response to regular spike trains.

A, layer 2/3 to layer 5 synapses operate optimally at low frequency (1 Hz; ^), but the amplitude of unitary EPSPs decreases greatly at the onset of a high-frequency regular spike train (red symbols; 47.6 Hz; 92 action potentials) to reach a steady-state value of 5 ± 0.05% (last 40 responses of the train; n = 5). Unitary EPSP amplitude has been normalized to the first 10 responses evoked at 1 Hz in each connection. B, under control extracellular ionic conditions (2 mm Ca2+/1 mm Mg2+) the amplitude of layer 5 to layer 5 uEPSPs facilitates at the onset of an identical high-frequency spike train (red symbols) and is maintained at a facilitated level throughout the train (171.4 ± 2.1%, last 40 responses of the train; n = 7). An increase in extracellular calcium levels (high Ca2+; 4 mm Ca2+/1 mm Mg2+; n = 3) resulted in the appearance of synaptic depression during the course of the high-frequency spike train (continuous black line, negative-going error bars). The insets in A and B show representative examples of uEPSPs evoked by the high-frequency spike train in these pathways under control ionic conditions.

Figure 6. Synaptic depression in layer 2/3 pyramidal neuron networks.

A, properties of layer 2/3 to layer 2/3 synaptic transmission. Note the pronounced synaptic depression following transition from a low frequency (1 Hz, open symbols) to a complex pattern of action potential firing pattern (red symbols); the line is a mono-exponential function with τ= 3.3 action potentials (n = 7 connections). The inset shows overlaid unitary EPSPs evoked during the complex spike train. B, random patterns of action potential firing (Vpre, five overlaid records) evoke rapid and strong depression of layer 2/3 to layer 5 synaptic transmission (Vpost; black traces, sequential trials; red trace, average of 40 repetitions). C, pathway-specific dynamics of transmission evoked by the generation of random patterns of action potential firing in layer 2/3 to layer 5 (^, n = 5) and layer 5 to layer 5 (•, n = 5) connections (data normalized in each connection to the first unitary EPSP of the train). Note the pronounced layer 2/3 to layer 5 synaptic depression, the evolution of which was well approximated with a mono-exponential function (red line; τ= 3.4 action potentials).

Layer 5 to layer 5 synaptic connections were capable of robust transmitter release throughout the course of the complex spike train (Fig. 4A and C). In contrast to layer 2/3 to layer 5 connections, uEPSPs evoked at 1 Hz between layer 5 pyramidal neurons showed a high failure rate (33.5 ± 4.2%; n = 18), suggesting that the layer 5 pathway transmits low-frequency rates unreliably. Upon transition to the complex spike train, however, the amplitude of uEPSPs increased over the first few action potentials of the train to 215.7 ± 19.0% of that generated at 1 Hz (range, 109.0–402.9%; amplitude at 1 Hz, 258.0 ± 37.7 μV; facilitation, 496.7 ± 60.9 μV; n = 18; Fig. 4C and E red symbols). It is remarkable that as the complex spike train evolved, the amplitude of uEPSPs did not depress (average throughout complex train, 261.8 ± 43.5 μV; first 20 action potentials, 302.5 ± 44.7 μV: last 20 action potentials, 244.5 ± 41.8 μV; n = 18; Fig. 4E). In single connections, the pattern of layer 5 to layer 5 uEPSP facilitation was stable from trial to trial and measurable uEPSPs were generated throughout the complex spike train (compare Fig. 4C left and right panels). Similarly, during the course of long spike trains generated regularly at the mean frequency of the complex spike train (47.6 Hz train), facilitation of layer 5 to layer 5 uEPSPs was maintained throughout the duration of the train (92 action potential; first 20 action potentials compared to 1 Hz, 187.5 ± 5.5%; last 20 action potentials, 167.2 ± 2.8%; amplitude at 1 Hz, 214.2 ± 5.1 μV; first 20 action potentials of the spike train, 373.9 ± 10.9 μV; n = 7; Fig. 5B). Moreover, we found that when the complex spike train was reproduced twice in close succession (20 ms delay), the amplitude of layer 5 to layer 5 uEPSPs evoked during the first and second repetition of the complex spike train did not depress in comparison to uEPSPs generated at 1 Hz (1 Hz: range, 32–699 μV; median, 90.8 μV; first complex spike train (92 action potentials): range, 66–604 μV; median, 197.8 μV; second complex spike train (92 action potentials): range, 49.3–404 μV; median, 167.4 μV; Kruskal–Wallis test, P > 0.71; n = 7; Mann–Whitney U test between first and second train, P > 0.38). Although these data do not address the limits of sustained transmission in layer 5 to layer 5 connections, they indicate that these synapsesa can sustain neurotransmitter release at high action potential firing frequencies (mean, 47.6 Hz) for at least 184 action potentials.

To explore whether other synaptic targets of layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons exhibit frequency-dependent synaptic depression, we recorded uEPSPs between pairs of layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons. In common with layer 2/3 to layer 5 connections, unitary layer 2/3 to layer 2/3 EPSPs showed rapid and strong depression upon transition from low frequency to complex action potential firing patterns (action potential constant, 3.3; 1 Hz, 387.5 ± 3.6 μV; last 40 action potentials of complex train, 13.1 ± 2.0 μV; n = 7), but recovered rapidly to an augmented level following the reappearance of low-frequency activity (recovery, τ= 1.29 s; 1 Hz before, 387.5 ± 3.6 μV; 1 Hz 20 action potentials after, 524.9 ± 11.2 μV; P < 0.0001; n = 7; Fig. 6A). These data indicate that synaptic transmission depresses strongly at both supra- and infra-granular synaptic targets of layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons when challenged by prolonged spike trains.

To examine the mechanisms underlying this form of depression, we first examined whether depression was caused by a failure of transmitter release or by the desensitization and/or saturation of postsynaptic AMPA receptors (Trussell et al. 1993; Silver et al. 2003). Synaptic depression at layer 2/3 to layer 5 synaptic connections was insensitive to blockade of AMPA receptor desensitization with cyclothiazide (CTZ; 100 μm) or the partial receptor antagonism of AMPA receptors with kynurenic acid (1 mm) (depression with CTZ: action potential constant, 2.8; amplitude at 1 Hz, 643.2 ± 3.6 μV; last 40 action potentials of complex train, 36.6 ± 6.9 μV; depression with kynurenic acid: action potential constant, 2.3; amplitude at 1 Hz, 187.1 ± 4.7 μV; last 40 action potentials of complex train, 14.3 ± 2.7 μV; in the continual presence of d-2-(–)-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (100 μm); Supplementary Fig. 3. Taken together, these data suggest that the pathway-specific, use-dependent properties of intracortical excitatory transmission have a presynaptic locus.

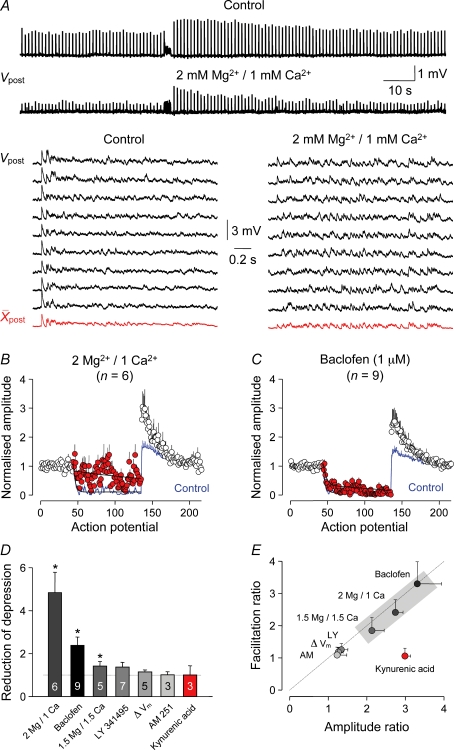

Modulation reveals mechanistic differences between excitatory intracortical synapses

A salient difference between intracortical excitatory synapses is their ability to transmit low-frequency activity (Figs 1–6). We hypothesized that faithful low-frequency transmission in layer 2/3 to layer 2/3 to layer 5 circuits was due to a relatively high release probability (Pr) at this distributed synapse (Abbott et al. 1997; Tsodyks & Markram, 1997; Silver et al. 2003; Abbott & Regehr, 2004). To investigate whether modulation of Pr impacted on the use-dependent properties of layer 2/3 to layer 5 synapses, we recorded uEPSPs under standard ionic conditions (2 mm Ca2+/1 mm Mg2+) and in the presence of low [Ca2+]o (1 mm Ca2+/2 mm Mg2+). Ionic substitution changed the dynamics of synaptic activity evoked during continual use, decreasing the amplitude of layer 2/3 to layer 5 uEPSPs evoked at low frequency to 37.2 ± 2.7% of control (n = 6; Fig. 7A) and transforming the pattern of synaptic depression during the complex spike train by slowing the time course and decreasing the magnitude of depression (control: action potential constant, 2.7; amplitude at 1 Hz, 847.3 ± 4.1 μV; last 40 action potentials of complex train, 57.0 ± 6.7 μV; 1 mm Ca2+/2 mm Mg2+: action potential constant, 142.7; amplitude at 1 Hz, 313.4 ± 3.3 μV; last 40 action potentials of the complex spike train, 153.5 ± 11.2 μV; n = 6; Fig. 7A and B). These data indicate that the axons of layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons are capable of transmitting action potentials at high frequencies (Supplementary Fig. 4) and show that a modulation of the probability of transmitter release can alter the ability of layer 2/3 to layer 5 synapses to sustain transmitter release through the course of long spike trains. To our surprise, this reduction of synaptic depression was accompanied by a dramatic increase of synaptic augmentation at the termination of complex spike trains (control, 1.54 ± 0.11; 1 mm Ca2+/2 mm Mg2+, 2.34 ± 0.37; P < 0.02; control: decay, τ= 33.0 s; 1 mm Ca2+/2 mm Mg2: decay, τ= 20.0 s; n = 6; Fig. 7B). A more conservative change of [Ca2+/Mg2+]o to 1.5/1.5 mm, had less pronounced, although statistically significant, effects on the dynamics of layer 2/3 to layer 5 uEPSPs (n = 5; Fig. 7D and E). By contrast, we found that an increase in the probability of release at layer 5 to layer 5 synapses, produced by changing the [Ca2+/Mg2+]o to 4 mm Ca2+/1 mm Mg2+, transformed the ability of these synapses to sustain release through the course of long spike trains, revealing the presence of synaptic depression (last 40 action potentials compared to 1 Hz: control, 171.4 ± 2.1%; n = 7; 4 mm Ca2+/1 mm Mg2+, 49.3 ± 0.1%; n = 3; P < 0.001; Fig. 5B). It should be noted, however, that the degree of synaptic depression apparent at layer 5 to layer 5 synapses revealed under conditions of increased Pr was modest in comparison to the magnitude of depression at layer 2/3 to layer 5 synapses under control ionic conditions (compare Fig. 5A and B).

Figure 7. Modulation of layer 2/3 to layer 5 synaptic transmission.

A, continuous voltage records of unitary EPSPs (Vpost) evoked in control (2 mm Ca2+/1 mm Mg2+) and in the presence extracellularly of 1 mm Ca2+/2 mm Mg2+. The lower traces show sequential single and averaged responses evoked by the complex spike train under the indicated conditions. B, the magnitude and time course of synaptic depression during the complex spike train in control (blue line) and 1 mm Ca2+/2 mm Mg2+ (1 Hz, open symbols; complex, red symbols). Data from each connection have been normalized under the indicated conditions to the first 10 uEPSPs generated at 1 Hz. The black lines are mono-exponential fits to the evolution of depression. C, baclofen weakly decreases synaptic depression (open and red symbols) relative to control (blue line). The black lines are mono-exponential fits to the evolution of depression through the complex spike train. D, summary data describing the modulation of synaptic depression. Values represent the ratio of the degree of synaptic depression in control and the indicated test condition; values > 1 represent a reduction of depression. The number of connections and statistical significance (*, P < 0.05; paired Student's t test). E, the reduction of unitary EPSP amplitude evoked at low frequency (1 Hz; ratio of control/condition, values > 1 indicate reduction) is related to the magnitude of synaptic augmentation (ratio of condition/control, values > 1 indicate increase). The grey shaded area delineates conditions that are statistically significant for both parameters; kynurenic acid (1 mm, red) significantly reduced unitary EPSP amplitude but did not alter synaptic augmentation.

As a next step we examined whether modulation of Pr by the activation of neurotransmitter systems controlled the dynamic behaviour of layer 2/3 to layer 5 synapses. The bath application of the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen (1 μm) (Vigot et al. 2006) decreased the amplitude of layer 2/3 to layer 5 uEPSPs evoked at low frequency to a similar degree as decreasing [Ca2+]o (% of control, 39.1 ± 6.9; P < 0.03; n = 9). By contrast, baclofen only weakly modulated the transmission of complex spike trains, modestly slowing the time course and decreasing the magnitude of synaptic depression (control: action potential constant, 3.1; depression, 11.2 ± 2.6% relative to 1 Hz; baclofen: action potential constant, 11.4; depression, 23.1 ± 5.8%; P < 0.01; n = 9; Fig. 7C). Augmentation following the complex spike train was, however, powerfully facilitated (control, 1.41 ± 0.08; baclofen, 2.17 ± 0.31; P < 0.02; control: decay, τ= 74.0 s; baclofen: decay, τ= 26.0 s; n = 9; Fig. 7C). In summary, we found a tight relationship between the ability of layer 2/3 to layer 5 synapses to faithfully transmit low-frequency activity and the degree of synaptic augmentation (r2= 0.98; uncorrelated probability, P < 0.0002; Fig. 6E). The modulation of low-frequency transmission did not, however, predict the degree of synaptic depression at higher frequencies of activation.

In contrast to the activation of presynaptic neurotransmitter systems, we found that a broad sprectrum antagonist of metabotropic glutamate (1 or 10 μm; (2S)-2-amino-2-[(1S,2S)-2-carboxycycloprop-1-yl](xanth-9-yl) propanoic acid (LY341495) (n = 7) or cannabinoid type 1 receptors (10 μm; N-(piperidin-1-yl)-5-(4-iodophenyl)-1-(2,4,dichlorophenyl)-4-methyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamide (AM 251) (n = 3) had no influence on the dynamics of synaptic transmission, suggesting that neither glutamate spillover nor the formation of an endocannabinoid-dependent retrograde signal to presynaptic sites are influential under our experimental conditions (Fig. 7D and E). Furthermore, manipulations of the somatic membrane potential did not modulate synaptic transmission in layer 2/3 to layer 5 circuits (rest, 79.9 ± 2.2 mV; depolarized, 53.3 ± 2.5 mV; n = 5; Fig. 7D and E) (Alle & Geiger, 2006; Shu et al. 2006). Similarly alteration of the amplitude and shape of presynaptic action potentials, by the inclusion of the potassium channel blocker 4-aminopyridine (4-AP; 2 mm) in the intrapipette solution (Debanne et al. 1997), failed to alter the dynamics of synaptic transmission (n = 7; Supplementary Fig. 5).

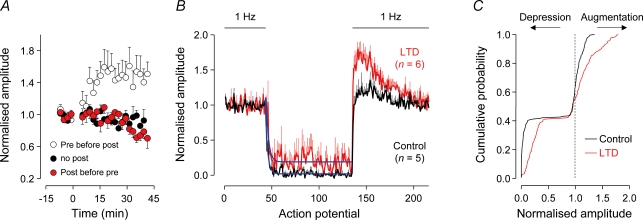

Next we investigated whether the dynamics of excitatory transmission at layer 2/3 to layer 5 synapses could be influenced by the induction of long-term changes of synaptic efficacy. Long-term changes of synaptic efficacy may be evoked at intracortical excitatory synapses using spike timing-dependent protocols, with the sign (potentiation or depression) dependent upon the temporal order of pre- and postsynaptic firing (Markram & Tsodyks, 1996; Sjostrom et al. 2001, 2003). As long-term depression (LTD) has been found to be mediated predominately by presynaptic mechanisms in the neocortex (Sjostrom et al. 2003), we examined whether the induction of LTD could modulate the dynamic properties of layer 2/3 to layer 5 synaptic transmission (Fig. 8). In support of previous observations, we observed that the sign of long-term changes of layer 2/3 to layer 5 uEPSP amplitude when evoked at low frequency (0.2 Hz) was sensitive to the timing of pre- and postsynaptic action potential firing during an induction period (260 action potentials at 1 Hz; control, presynaptic not paired with postsynaptic action potential firing: 0.94 ± 0.06 of baseline uEPSP amplitude 34–38 min after induction protocol; n = 5; long-term potentiation, presynaptic preceded postsynaptic by 10 ms: 1.53 ± 0.22; 28–32 min after induction; P < 0.05; n = 5; LTD, postsynaptic preceded presynaptic by 10 ms: 0.78 ± 0.07, 34–38 min after induction; P < 0.05; n = 9; Fig. 8A). In layer 2/3 to layer 5 connections that exhibited stable LTD, we explored whether synaptic depression during prolonged, complex spike trains was altered. We found in neurons where LTD was established, a significant reduction in the magnitude of synaptic depression during and an increase in synaptic augmentation following the complex spike train, relative to connections that had been recorded for a similar period of time and were subject to an a identical presynaptic induction protocol that was not paired with postsynaptic firing (depression during train, percentage of 1 Hz activity: control, 4.4 ± 0.4%; LTD, 24.5 ± 13.2%; P < 0.005, Mann–Whitney U test; augmentation: control: 1.18 ± 0.11; LTD: 1.62 ± 0.10; P < 0.03, Mann–Whitney U test; control: n = 5; LTD: n = 6; Fig. 8B and C). LTD can therefore alter the dynamics of layer 2/3 to layer 5 synaptic transmission, depressing transmission at low frequency (Fig. 8A), but decreasing the degree of synaptic depression apparent during periods of high-frequency activation (Fig. 8B and C).

Figure 8. The use-dependent dynamics of synaptic transmission are modulated by the induction of synaptic plasticity at layer 2/3 to layer 5 synapses.

A, long-term potentiation and depression (LTD) of layer 2/3 to layer 5 unitary EPSP amplitude. At time zero, a pairing protocol of pre- and postsynaptic action potential firing was applied (difference in time is 10 ms; 260 action potentials; control connections received only presynaptic firing). The amplitude of EPSPs was normalized to pre-induction values in each connection. B, the induction of LTD (red) decreased the degree of synaptic depression during and increased the magnitude of augmentation following the presentation of the complex spike train (92 action potentials; mean frequency, 47.6 Hz), relative to control connections (black). Blue lines are exponential fits to the time course of depression. C, cumulative distributions of the pooled data shown in B demonstrate the influence of LTD on synaptic depression during and augmentation following the complex spike train.

Properties of layer 2/3 to layer 5 synaptic augmentation

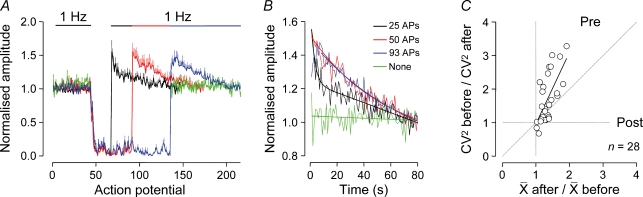

A feature of the dynamics of layer 2/3 to layer 5 synaptic transmission was the long-lasting period of uEPSP augmentation following the termination of complex high-frequency firing patterns (Figs 4–7). The properties of synaptic augmentation were causally related to those of the preceding spike train (Fig. 9). Augmentation was absent if the complex spike train was replaced by a period of quiescence (n = 6; Fig. 9A and B green), and the time course, but not the magnitude of synaptic augmentation, was dictated by the number of action potentials in the spike train (n = 9; Fig. 9A and B). To examine whether augmentation was mediated by a pre- or postsynaptic mechanism, we analysed the amplitude distributions of 20 uEPSPs evoked at 1 Hz before and after the complex spike train across many trials in each connection (average number of uEPSPs in distributions, 443 ± 38; n = 28 unitary connections). Augmentation was mediated by a significant increase of the mean uEPSP amplitude, unaccompanied by an increase in the standard deviation of amplitude distributions (ratio amplitude before/after, 1.35 ± 0.04; P < 0.0001; ratio standard deviation before/after, 1.08 ± 0.03; P > 0.05). Consequently, when we plotted the ratio of mean uEPSP amplitude recorded before and after the complex spike train against the ratio of the coefficient of variation squared (CV2), we obtained results consistent with a presynaptic locus of synaptic augmentation (Faber & Korn, 1991) (r2= 0.45; uncorrelated probability, P < 0.0001; Fig. 9C).

Figure 9. Properties of layer 2/3 to layer 5 synaptic augmentation.

A, complex trains of action potential firing generate long-lasting augmentation of low-frequency layer 2/3 to layer 5 synaptic activity. A saturatable relationship exists between the time course of augmentation and the number of action potentials in complex spike trains (amplitude normalized to the first 10 unitary EPSPs evoked at 1 Hz for each connection; continuous lines show mean values and vertical lines represent s.e.m.; n = 9 connections; the number of action potentials shown in B refers to the number of action potentials of the complex spike train). Augmentation is absent if the complex spike train is replaced by a period of quiescence (green; n = 6 connections). B, the decay kinetics of augmentation are determined by action potential number. Note the rapid, bi-exponential decay of augmentation in response to 25 action potentials (black). C, augmentation is mediated by a presynaptic (Pre) mechanism. Plot of the ratios of mean amplitude and coefficient of variation squared (CV2) of uEPSPs recorded before and after the complex spike train (n = 28 connections). The line represents a linear regression (r2= 0.45; uncorrelated probability, P < 0.0001).

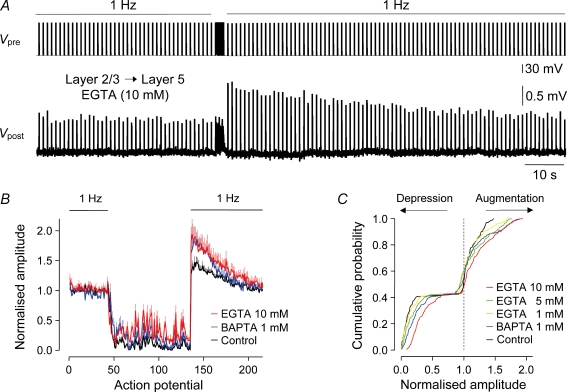

Previous observations have demonstrated that periods of sustained presynaptic action potential firing can lead to augmentation of synaptic transmission (Swandulla et al. 1991; Delaney & Tank, 1994; Kamiya & Zucker, 1994; Atluri & Regehr, 1996; Habets & Borst, 2005). At these central and peripheral synapses, augmentation has been found to be accompanied by elevated terminal [Ca2+]i and can be sensitive to calcium chelators (Swandulla et al. 1991; Kamiya & Zucker, 1994; Atluri & Regehr, 1996; but see Wojtowicz & Atwood, 1988; Tanabe & Kijima, 1989, 1992). We therefore explored whether the chelation of terminal [Ca2+]i by the free diffusion of calcium chelators from the presynaptic recording pipette would influence the augmentation of layer 2/3 to layer 5 synaptic transmission. To our surprise, we found that introduction of the calcium chelators BAPTA (1 mm; n = 5) or EGTA (1, 5 or 10 mm; n = 5, 14 and 6, respectively) did not block, but significantly increased the magnitude of augmentation following complex spike trains when compared with control connections (ANOVA; P < 0.01 each group, Dunnett's post hoc test; Fig. 10). The actions of chelators on the magnitude of augmentation were accompanied by a concentration-dependent decrease of synaptic depression during the complex spike train, suggesting that calcium chelators reached presynaptic terminals and were influential in controlling transmitter release (Rozov et al. 2001), but not augmentation (Fig. 10B and C).

Figure 10. Augmentation of layer 2/3 to layer 5 synaptic transmission is resistant to presynaptic calcium chelators.

A, continuous voltage records show augmentation of layer 2/3 to layer 5 unitary EPSPs (Vpost) evoked at 1 Hz following the generation of the complex spike train. The presynaptic layer 2/3 pyramidal neuron (Vpre) was recorded with a pipette containing EGTA (10 mm). B, pooled data show the magnitude and time course of augmentation in layer 2/3 to layer 5 connections tested with the indicated presynaptic intrapipette contents (control, n = 12; BAPTA 1 mm, n = 5; EGTA 10 mm, n = 6). Note that calcium chelators dramatically altered the dynamics of synaptic transmission during the complex spike train. C, cumulative distributions of the pooled data shown in B demonstrate the influence of the calcium chelators EGTA and BAPTA on depression during and augmentation following the complex spike train.

Discussion

The main findings of the present study are that the use-dependent properties of excitatory synaptic transmission in intracortical circuits are not uniform, but are layer- and pathway-specific. The synaptic output of layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons was dominated by frequency-dependent depression and was incapable of signalling long trains of high frequency (> 10 Hz) presynaptic action potential firing at infra- and supra-granular pyramidal neuron targets. By contrast, layer 5 to layer 5 synaptic transmission faithfully transmitted each action potential and sustained release throughout long trains of action potential firing generated at instantaneous frequencies of up to 300 Hz.

Pathway-specific dynamics of excitatory neurotransmission

The efficacy of synaptic transmission during trains of action potentials is determined by pre- and postsynaptic factors (Zucker & Regehr, 2002; Abbott & Regehr, 2004). Here, we have excluded postsynaptic factors, such as the desensitization and saturation of postsynaptic receptors, and the non-linear dendritic integration of EPSPs, as major determinants of the dynamics of intracortical excitatory synaptic transmission. Pathway-specific differences in the use-dependent dynamics of synaptic transmission are therefore likely to have arisen by presynaptic mechanisms. The frequency-following capacity of excitatory synapses is known to be limited by the supply of release-competent synaptic vesicles, and depression is mediated by an emptying of a readily releasable pool of synaptic vesicles at each synaptic contact (Rosenmund & Stevens, 1996; Dobrunz & Stevens, 1997), the refractoriness of vesicular sites (Dittman et al. 2000; Hefft et al. 2002) and/or by a decrease of action potential triggered [Ca2+]i (Xu & Wu, 2005). Therefore pathway-specific differences in the use-dependent dynamics of synaptic transmission observed here could have arisen because of a difference in the number of synaptic contacts between neocortical pyramidal neurons. The estimated number of synapses formed by the axon of a presynaptic layer 2/3 or layer 5 pyramidal neuron with a postsynaptic layer 5 pyramidal neuron in brain slices is, however, similar in the two groups (Markram et al. 1997; Thomson & Bannister, 1998), but their subcellular targeting is distinct (Markram et al. 1997; Williams & Stuart, 2002; Sjostrom & Hausser, 2006). We found that the amplitude of unitary layer 2/3 to layer 5 and layer 5 to layer 5 EPSPs are similar when evoked at low frequency and failures of transmission were excluded from amplitude distributions. By contrast, when failures of transmission were included in this analysis, layer 2/3 to layer 5 uEPSPs were of significantly greater amplitude across our population of unitary connections (layer 2/3 to layer 5, 417.0 ± 36.9 μV; n = 140; layer 5 to layer 5, 248.7 ± 26.3 μV; n = 42; P < 0.02). Indeed, under conditions of continual use, low-frequency activation of layer 2/3 to layer 5 synapses resulted in only occasional failure of release, whereas layer 5 to layer 5 synapses exhibited a high failure rate (Williams, 2005). The probability of release is therefore a major determinant of the efficacy of intracortical excitatory synaptic transmission during low-frequency patterns of action potential firing. This notion is supported by the pathway-specific difference in paired-pulse behaviour observed here. It should be noted, however, that such a relationship is not simple, as we found a correlation between the presumed dendritic site of layer 2/3 to layer 5 synaptic contacts and paired-pulse dynamics (Williams & Stuart, 2002) and a heterogeneity of paired-pulse behaviour for layer 5 to layer 5 synaptic connections, with a fraction (3 of 42) of layer 5 to layer 5 contacts exhibiting paired-pulse depression. Heterogeneity may have resulted from the pooling of connections recorded from different cortical areas (Atzori et al. 2001) or at different developmental stages (Reyes & Sakmann, 1999). However, we observed a similar degree of heterogeneity for recordings made from single brain slices and occasionally among groups of simultaneously recorded neurons.

In contrast to low-frequency activation, during prolonged higher-frequency activation, such as the simple and complex spike trains used here, models suggest that neurotransmitter release is not determined by Pr, but by the availability of release-competent vesicles (Abbott et al. 1997; Tsodyks & Markram, 1997). The pathway-specific properties of synaptic transmission are, therefore, consistent with the idea that the kinetics of vesicle supply or the size of the releasable pool of vesicles at layer 2/3 to layer 5 and at layer 5 to layer 5 synapses are distinct. To investigate this relationship, we altered the Pr by lowering [Ca2+]o, or by activating presynaptic GABAB receptors, and found that both resulted in a ∼3-fold reduction of uEPSP amplitude at low frequencies of activation. To our surprise, the reduction of [Ca2+]o from 2 to 1 mm enhanced the ability of layer 2/3 to layer 5 synapses to transmit complex spike trains, greatly reducing the degree and slowing the time course of synaptic depression, whereas baclofen had only modest effects. Layer 2/3 to layer 5 synaptic transmission of complex spike trains is therefore determined by the magnitude of presynaptic action potential-gated calcium entry. The frequency-dependent control of neurotransmission by presynaptic GABAB receptors, a class of G-protein-coupled receptors (Vigot et al. 2006), is explained by the frequency-dependent relief of calcium channel inhibition by G-proteins (Park & Dunlap, 1998; Mitchell & Silver, 2000; Hefft et al. 2002). The calcium-dependence of layer 2/3 to layer 5 transmission indicates that the pathway-specific transmission of complex firing patterns may be explained by a proportionally greater presynaptic action potential-triggered calcium signal at layer 2/3 to layer 5 synapses, thereby setting a relatively high Pr and leading to the rapid depletion of the releasable vesicular pool during repeated activation. This idea was supported by the generation of frequency-dependent synaptic depression in layer 5 to layer 5 connections when extracellular calcium levels were raised. Indeed, a recent elegant imaging study has shown that calcium entry at single layer 2/3 pyramidal neuron axonal boutons is greater for sites that drive frequency-dependent depression in postsynaptic interneurons, than for sites mediating facilitation (Koester & Johnston, 2005). It would be informative to apply these techniques to layer 2/3 to layer 5 and layer 5 to layer 5 synaptic contacts to establish the relative contribution of presynaptic calcium entry and synapse-specific differences in the kinetics of depletion or size of the readily releasable pool to their ability to sustain neurotransmitter release.

Interestingly, we found that manipulations that increased the ability of layer 2/3 to layer 5 synapses to transmit complex spike trains, led to a dramatic augmentation of low-frequency synaptic transmission following a period of high-frequency activation. Augmentation of synaptic transmission has been observed in other central and peripheral synaptic connections after repeated activation (Swandulla et al. 1991; Delaney & Tank, 1994; Kamiya & Zucker, 1994; Atluri & Regehr, 1996; Habets & Borst, 2005). It is generally thought to occur as a result of a presynaptic mechanism, engaged by the continuing actions of residual intraterminal free Ca2+, elevated by the conditioning spike train (Swandulla et al. 1991; Delaney & Tank, 1994; Kamiya & Zucker, 1994; Atluri & Regehr, 1996; Habets & Borst, 2005). In support of this, we found that the time course of augmentation is controlled by the duration of the conditioning train and is generated by a presynaptic mechanism. However, augmentation was proportionally increased when intraterminal Ca2+ entry was decreased. This could be explained if low Pr synapses are more sensitive or have a wider dynamic range of modulation by intraterminal residual free Ca2+. However, only modest augmentation at low Pr layer 5 to layer 5 synapses was observed, indicating that this form of augmentation is a property of the layer 2/3 to layer 5 pathway. In conflict with the residual free calcium hypothesis, we found that loading presynaptic layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons with the Ca2+ chelators EGTA or BAPTA did not block augmentation (Swandulla et al. 1991; Kamiya & Zucker, 1994). In support of our findings, others have observed that forms of synaptic facilitation and augmentation can be insensitive to intraterminal calcium chelation (Wojtowicz & Atwood, 1988; Tanabe & Kijima, 1989, 1992) and uncorrelated with the concentration of free intraterminal Ca2+ (Blundon et al. 1993). We are confident that calcium chelators reached synaptic terminals and were not saturated during the course of spike trains (see Kamiya & Zucker, 1994), as chelators decreased the degree of synaptic depression throughout complex trains in a dose-dependent manner, presumably by blunting [Ca2+] close to release sites (Rozov et al. 2001). These data may suggest that the calcium sensitivity of release and augmentation are dissociable, or that augmentation is not generated as a consequence of residual free intraterminal calcium, but rather mediated by the action of Ca2+ bound to site(s) that influence synaptic release (Katz & Miledi, 1968; Blundon et al. 1993; Matveev et al. 2006) following the transient and local elevation of [Ca2+] during a conditioning train. Functionally, such augmentation will act to increase the gain of the layer 2/3 to layer 5 pathway in a manner analogous to the potentiation of spinal reflexes mediated by augmentation of group 1a afferent inputs to spinal motoneurons (Curtis & Eccles, 1960).

Implications for neocortical network function

The functional impact of the described layer- and pathway-specific dynamics of excitatory synaptic transmission will be dependent upon the action potential firing rate and pattern of pyramidal neurons in the behaving animal. Despite considerable investigation, the firing rate and pattern of neocortical pyramidal neurons under behaviourally relevant conditions are controversial. Seminal work on the visual cortex of awake cats revealed a high frequency of spontaneous and stimulus-evoked action potential firing (Hubel, 1959). Similarly, in the visual, somatosensory, motor and associational cortices of behaving cats and primates, extra- and intracellular recording techniques have revealed high spontaneous and stimulus-evoked action potential firing rates (Porter et al. 1971; Shadlen & Newsome, 1998; deCharms & Zador, 2000; Steriade et al. 2001; Krupa et al. 2004; Chen & Fetz, 2005; Luna et al. 2005). By contrast, spontaneous and stimulus-evoked action potential firing rates in the barrel cortex of the rat are low when examined by extracellular or patch-clamp recording techniques, suggesting a ‘sparse’ action potential code (Margrie et al. 2002; Brecht et al. 2004; Crochet & Petersen, 2006; de Kock et al. 2007). Recently, it has been suggested that this disparity results from recording method, with extracellular recording techniques favouring the detection of active neurons and so overestimating the level of network activity (Margrie et al. 2002; Shoham et al. 2006). This argument is strengthened by consideration of the metabolic demands imparted by high rates of action potential firing (Shoham et al. 2006). It should be noted, however, that studies of the rodent barrel cortex have typically examined sensory responses evoked by passive whisker deflection. By contrast, Krupa et al. (2004) have shown that the whisker-evoked action potential output of supra- and infra-granular neurons of the rat barrel cortex are profoundly increased when rats are engaged in a behaviourally relevant task. Thus under contrasting behavioural states, neocortical networks exhibit a wide frequency range of operation. Pathway-specific use-dependent dynamics of excitatory transmission may therefore function to selectively control neuronal excitability in pyramidal neurons networks, perhaps in a layer-specific manner. For example, synaptic depression may maintain a relatively low action potential firing rate within layer 2/3 pyramidal neuron networks, whereas synaptic facilitation in layer 5 circuits may allow higher frequencies of operation. In support of this notion, recent extracellular recordings have shown that large tufted layer 5 pyramidal neurons (the cell type recorded in the present study) are the most active neurons within the rat barrel cortex, firing spontaneously at relatively high rates and discharging with high probability to brief single-whisker passive defection (de Kock et al. 2007). Moreover, under states of higher activity, such as the high-frequency (> 50 Hz) firing of layer 5 pyramidal neurons prior to movement generation in the primate motor cortex (Porter & Muir, 1971), we speculate that the synaptic output of layer 5 pyramidal neurons will be powerfully engaged. Indeed, electrical stimulation of the cortico-spinal tract at such frequencies leads to powerful use-dependent synaptic facilitation in spinal motoneurons (Porter, 1970; Porter & Muir, 1971), suggesting that the use-dependent properties of synaptic transmission at subcortical targets of layer 5 pyramidal neurons in vivo are similar to those described here for intracortical targets of layer 5 pyramidal neurons in vitro. Our data suggest that the ability of layer 5 pyramidal neuron synapses to sustain release under conditions of continual use may help to explain the pivotal role played by these neurons in the genesis of sustained periods of network ‘up’ states and epileptiform activity in the neocortex (Connors, 1984; Sanchez-Vives & McCormick, 2000).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to J. Letzkus, S. Redman and G. Stuart for helpful discussions. S.R.W. performed all experiments, and S.E.A. made neuronal reconstructions. This work was supported by the Medical Research Council (UK).

Supplemental material

Online supplemental material for this paper can be accessed at: http://jp.physoc.org/cgi/content/full/jphysiol.2007.138453/DC1 and http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/suppl/10.1113/jphysiol.2007.138453

References

- Abbott LF, Regehr WG. Synaptic computation. Nature. 2004;431:796–803. doi: 10.1038/nature03010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbott LF, Varela JA, Sen K, Nelson SB. Synaptic depression and cortical gain control. Science. 1997;275:220–224. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alle H, Geiger JR. Combined analog and action potential coding in hippocampal mossy fibers. Science. 2006;311:1290–1293. doi: 10.1126/science.1119055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angulo MC, Staiger JF, Rossier J, Audinat E. Developmental synaptic changes increase the range of integrative capabilities of an identified excitatory neocortical connection. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1566–1576. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-05-01566.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arieli A, Sterkin A, Grinvald A, Aertsen A. Dynamics of ongoing activity: explanation of the large variability in evoked cortical responses. Science. 1996;273:1868–1871. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5283.1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atluri PP, Regehr WG. Determinants of the time course of facilitation at the granule cell to Purkinje cell synapse. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5661–5671. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-18-05661.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atzori M, Lei S, Evans DI, Kanold PO, Phillips-Tansey E, McIntyre O, McBain CJ. Differential synaptic processing separates stationary from transient inputs to the auditory cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1230–1237. doi: 10.1038/nn760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banitt Y, Martin KA, Segev I. Depressed responses of facilitatory synapses. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:865–870. doi: 10.1152/jn.00689.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blundon JA, Wright SN, Brodwick MS, Bittner GD. Residual free calcium is not responsible for facilitation of neurotransmitter release. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:9388–9392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolshakov VY, Siegelbaum SA. Regulation of hippocampal transmitter release during development and long-term potentiation. Science. 1995;269:1730–1734. doi: 10.1126/science.7569903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brecht M, Schneider M, Sakmann B, Margrie TW. Whisker movements evoked by stimulation of single pyramidal cells in rat motor cortex. Nature. 2004;427:704–710. doi: 10.1038/nature02266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buracas GT, Zador AM, Deweese MR, Albright TD. Efficient discrimination of temporal patterns by motion-sensitive neurons in primate visual cortex. Neuron. 1998;20:959–969. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80477-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Fetz EE. Characteristic membrane potential trajectories in primate sensorimotor cortex neurons recorded in vivo. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:2713–2725. doi: 10.1152/jn.00024.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors BW. Initiation of synchronized neuronal bursting in neocortex. Nature. 1984;310:685–687. doi: 10.1038/310685a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crochet S, Petersen CC. Correlating whisker behavior with membrane potential in barrel cortex of awake mice. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:608–610. doi: 10.1038/nn1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis DR, Eccles JC. Synaptic action during and after repetitive stimulation. J Physiol. 1960;150:374–398. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1960.sp006393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kock CP, Bruno RM, Spors H, Sakmann B. Layer- and cell-type-specific suprathreshold stimulus representation in rat primary somatosensory cortex. J Physiol. 2007;581:139–154. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.124321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debanne D, Guerineau NC, Gahwiler BH, Thompson SM. Action-potential propagation gated by an axonal I(A)-like K+ conductance in hippocampus. Nature. 1997;389:286–289. doi: 10.1038/38502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deCharms RC, Blake DT, Merzenich MM. Optimizing sound features for cortical neurons. Science. 1998;280:1439–1443. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5368.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deCharms RC, Zador A. Neural representation and the cortical code. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:613–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney KR, Tank DW. A quantitative measurement of the dependence of short-term synaptic enhancement on presynaptic residual calcium. J Neurosci. 1994;14:5885–5902. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-10-05885.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittman JS, Kreitzer AC, Regehr WG. Interplay between facilitation, depression, and residual calcium at three presynaptic terminals. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1374–1385. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01374.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrunz LE, Stevens CF. Heterogeneity of release probability, facilitation, and depletion at central synapses. Neuron. 1997;18:995–1008. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80338-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas RJ, Martin KA. Neuronal circuits of the neocortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:419–451. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber DS, Korn H. Applicability of the coefficient of variation method for analyzing synaptic plasticity. Biophys J. 1991;60:1288–1294. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82162-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Alfonso T, Ryan TA. The kinetics of synaptic vesicle pool depletion at CNS synaptic terminals. Neuron. 2004;41:943–953. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrmann G, Segev I, Markram H, Tsodyks M. Coding of temporal information by activity-dependent synapses. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:140–148. doi: 10.1152/jn.00258.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarreta M, Hestrin S. Frequency-dependent synaptic depression and the balance of excitation and inhibition in the neocortex. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:587–594. doi: 10.1038/2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert CD. Microcircuitry of the visual cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1983;6:217–247. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.06.030183.001245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habets RL, Borst JG. Post-tetanic potentiation in the rat calyx of Held synapse. J Physiol. 2005;564:173–187. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.079160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harsch A, Robinson HP. Postsynaptic variability of firing in rat cortical neurons: the roles of input synchronization and synaptic NMDA receptor conductance. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6181–6192. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06181.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefft S, Kraushaar U, Geiger JRP, Jonas P. Presynaptic short-term depression is maintained during regulation of transmitter release at a GABAergic synapse in rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 2002;539:201–208. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel DH. Single unit activity in striate cortex of unrestrained cats. J Physiol. 1959;147:226–238. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1959.sp006238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. Receptive fields of single neurones in the cat's striate cortex. J Physiol. 1959;148:574–591. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1959.sp006308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegaya Y, Aaron G, Cossart R, Aronov D, Lampl I, Ferster D, Yuste R. Synfire chains and cortical songs: temporal modules of cortical activity. Science. 2004;304:559–564. doi: 10.1126/science.1093173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa T, Sahara Y, Takahashi T. A single packet of transmitter does not saturate postsynaptic glutamate receptors. Neuron. 2002;34:613–621. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00692-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya H, Zucker RS. Residual Ca2+ and short-term synaptic plasticity. Nature. 1994;371:603–606. doi: 10.1038/371603a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B, Miledi R. The role of calcium in neuromuscular facilitation. J Physiol. 1968;195:481–492. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klyachko VA, Stevens CF. Temperature-dependent shift of balance among the components of short-term plasticity in hippocampal synapses. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6945–6957. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1382-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koester HJ, Johnston D. Target cell-dependent normalization of transmitter release at neocortical synapses. Science. 2005;308:863–866. doi: 10.1126/science.1100815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]