Abstract

Thalamic ventrobasal (VB) relay neurones express multiple GABAA receptor subtypes mediating phasic and tonic inhibition. During postnatal development, marked changes in subunit expression occur, presumably reflecting changes in functional properties of neuronal networks. The aims of this study were to characterize the properties of synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAA receptors of developing VB neurones and investigate the role of the α1 subunit during maturation of GABA-ergic transmission, using electrophysiology and immunohistochemistry in wild type (WT) and α10/0 mice and mice engineered to express diazepam-insensitive receptors (α1H101R, α2H101R). In immature brain, rapid (P8/9–P10/11) developmental change to mIPSC kinetics and increased expression of extrasynaptic receptors (P8–27) formed by the α4 and δ subunit occurred independently of the α1 subunit. Subsequently (≥ P15), synaptic α2 subunit/gephyrin clusters of WT VB neurones were replaced by those containing the α1 subunit. Surprisingly, in α10/0 VB neurones the frequency of mIPSCs decreased between P12 and P27, because the α2 subunit also disappeared from these cells. The loss of synaptic GABAA receptors led to a delayed disruption of gephyrin clusters. Despite these alterations, GABA-ergic terminals were preserved, perhaps maintaining tonic inhibition. These results demonstrate that maturation of synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAA receptors in VB follows a developmental programme independent of the α1 subunit. Changes to synaptic GABAA receptor function and the increased expression of extrasynaptic GABAA receptors represent two distinct mechanisms for fine-tuning GABA-ergic control of thalamic relay neurone activity during development.

GABAA receptors mediate fast GABA-ergic neurotransmission, and are assembled from a large family of subunits (Barnard et al. 1998). GABAA receptors differing in subunit composition are distinguished by their function, pharmacology, subcellular localization (e.g. synaptic versus extrasynaptic) and spatio-temporal expression patterns (Fritschy & Brünig, 2003; Korpi & Sinkkonen, 2006). This heterogeneity is exemplified in the adult rodent thalamus, which contains at least three major GABAA receptor populations (Wisden et al. 1992; Fritschy & Mohler, 1995; Zhang et al. 1997). In relay nuclei, such as VB, or the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN), synaptic (α1β2γ2) and extrasynaptic (α4β2δ) GABAA receptors coexist, whereas the reticular nucleus (nRT) and intralaminar nuclei mainly express synaptic α3β3γ2 GABAA receptors. These receptor populations have defined functional and pharmacological properties, with α1- and α3-GABAA receptors being diazepam sensitive and mediating phasic inhibition, whereas α4δ-GABAA receptors are diazepam insensitive, highly sensitive to neurosteroids and 4,5,6,7- tetrahydroisoxazolo-[5,4-c]pyridin-3-ol (THIP) and mediate tonic inhibition (Sur et al. 1999; Browne et al. 2001; Belelli et al. 2005; Jia et al. 2005; Farrant & Nusser, 2005; Chandra et al. 2006; Bright et al. 2007). At the network level, these distinct GABAA receptors contribute to the regulation of thalamocortical rhythmic activity associated with sleep, wakefulness and vigilance and are implicated in seizure disorders (Huntsman & Huguenard, 2000; Sohal et al. 2003).

The GABAA receptor subtypes of relay nuclei have a delayed expression during postnatal development. In rodents at birth, expression of α1, α4, β2 and δ subunits is low and relay neurones in the VB and LGN mainly express α2 and β3 subunits (Laurie et al. 1992; Fritschy et al. 1994). An apparent switch in expression occurs during brain maturation, with α1- gradually replacing α2-GABAA receptors, a re-organization proposed to influence the kinetics of IPSCs (Okada et al. 2000). In contrast, in the nRT, α3-GABAA receptors are abundant at every postnatal age examined, although a transient expression of the α5 subunit around P7 has been reported (Studer et al. 2006). The presence of multiple GABAA receptor subtypes within single neurones (α2- in immature and α1- and α4-GABAA receptors in mature relay neurones) raises the question of how their assembly and subcellular targeting are regulated, and to what extent their function is determined by subunit composition. Thus, developing VB neurones represent an excellent model to address these fundamental questions.

Here, we investigated the changes to GABAA receptors in VB neurones during postnatal ontogeny using electrophysiological and morphological approaches in wild-type (WT), α1 subunit null (α10/0) β2 subunit null (β20/0) and ‘knock-in’α1H101R and α2H101R mice (McKernan et al. 2000; Sur et al. 2001; Vicini et al. 2001). Importantly, the developmental change to mIPSC kinetics (which plays a critical role in thalamo-cortical oscillations) and the establishment of extrasynaptic receptors, occurred independently of the α1 subunit. Unexpectedly, the mIPSCs of α10/0 VB neurones disappeared during maturation, indicating that the α2 subunit was not replaced. Therefore, we used immunohistochemistry for GABAA receptor subunits and pre- and postsynaptic markers of GABA-ergic transmission to determine how this loss of function affects GABA-ergic synapses in VB neurones of α10/0 mice. Intriguingly, the disruption of synaptic transmission caused by deletion of the α1 subunit had no effect on extrasynaptic receptor expression, which increased with development (P8–27) similarly for VB neurones derived from WT and α10/0 mice.

Methods

All experiments have been approved by the local authorities and were performed in accordance with European Community Council Directive 86/609/EEC and with the institutional guidelines of the Universities of Zurich and Dundee.

Thalamic slice preparation and electrophysiology

The α1H101R, α2H101R, β20/0 and α10/0 mice utilized for electrophysiological experiments were generated on a mixed C57BL6–129SvEv background at the Merck Sharp & Dohme Research Laboratories at the Neuroscience Research Centre in Harlow as previously described (McKernan et al. 2000; Sur et al. 2001). Experiments were conducted on slices prepared from the first two generations of WT, α1H101R, α2H101R,β20/0 and α10/0 breeding pairs derived from the corresponding heterozygous +/0 mice bred at the University of Dundee.

Thalamic slices were prepared from mice of either sex (P8–27) according to standard protocols (Belelli et al. 2005). Animals were killed by cervical dislocation in accordance with Schedule 1 of the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. The brain was rapidly removed and placed in oxygenated ‘ice cold’ maintenance solution containing (mm): 225 sucrose, 2.95 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 0.5 CaCl2, 10 MgSO4, 10 d-glucose (pH of 7.4; 330–340 mosmol l−1). The tissue was maintained in this ‘ice-cold’ solution whilst horizontal 300–400 μm slices were cut using a Vibratome (St Louis, MO, USA). The slices were incubated at 32°C for 1 h in an oxygenated, extracellular solution (ECS) containing (mm): 126 NaCl, 2.95 KCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 CaCl2, 10 d-glucose and 2 MgCl2 (pH 7.4; 300–310 mosmol l−1). Subsequently, slices were maintained at room temperature (20–23°C) before being used for recordings. Whole-cell patch clamp recordings were performed at 35°C from thalamic nucleus reticularis (nRT) and VB neurones visually identified with an Olympus BX51 microscope (Olympus, Southall, UK) equipped with DIC/IR optics as previously described (Belelli et al. 2005). Patch pipettes were prepared from thick walled borosilicate glass (Garner Glass Co., Claremont, CA, USA) and had open tip resistances of 3–5 MΩ when filled with an intracellular solution that contained (mm): 140 CsCl, 10 HEPES, 10 EGTA, 2 Mg-ATP, 1 CaCl2, 5 QX-314 (pH 7.3 with CsOH, 300–305 mosmol l−1). Miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) were recorded using an Axopatch 1D or 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA) at a holding potential of −60 mV in ECS that, additionally contained 2 mm kynurenic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, UK) and 0.5 μm tetrodotoxin (TTX; Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK) to block ionotropic glutamate receptors and sodium-dependent action potentials, respectively. Series resistance and whole-cell capacitance were estimated by cancelling the fast current transients evoked at the onset and offset of brief (10–20 ms) 3–5 mV voltage-command steps. Series resistance ranged between 5 and 16mΩ. Series resistance compensation of 60–80% was employed in the presence of lag values of 10–20 μs. Recordings were discarded if the series resistance changed (10% tolerance) during the course of the experiment. Currents were filtered at 2 kHz using an 8-pole low pass Bessel filter and recorded on to digital audio tape using a DTR 1205 recorder for subsequent offline analysis.

Drugs

THIP (gaboxadol, 10−2m), bicuculline metho-bromide (10−2m), strychnine (10−3m) and nipecotic acid (10−1m) were dissolved in water, whereas zolpidem was prepared as a concentrated (1000×) stock solution in DMSO. These stock solutions were diluted in ECS to the desired concentration. The final maximum DMSO concentration (0.1%v/v) had no effect on mIPSCs, or the tonic current. All modulatory agents were applied via the perfusion system (2–4 ml min−1) and allowed to infiltrate the slice for a minimum of 10 min while recordings were acquired. With the exception of THIP, which was a generous gift of Bjarke Ebert (H. Lundbeck A/S, Copenhagen Valby, Denmark), and TP003 (Merck Sharp & Dohme – see Dias et al. 2005) all drugs tested were obtained from either Sigma-Aldrich, UK, or Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK).

Data analysis

Data was analysed offline using the Strathclyde Electrophysiology Software, WinEDR/WinWCP (J. Dempster, University of Strathclyde, UK). Individual mIPSCs were detected using a −4 pA amplitude threshold detection algorithm and visually inspected for validity. Accepted events were analysed for peak amplitude, 10–90% rise time, charge transfer and time for events to decay from peak by 90% (T90). To minimize the contribution of dendritically generated currents, which are subject to cable filtering, analysis was restricted to events with a rise time ≤ 1 ms. A minimum of 100 accepted events per cell were digitally averaged by alignment at the mid-point of the rising phase, and the mIPSC decay fitted by either monoexponential (y(t) =Ae(−t/τ)), or biexponential (y(t) =A1e(- t/τ1)+A2e(- t/τ2)) functions using the least squares method, where A is amplitude, t is time and τ is the decay time constant. Analysis of the s.d. of residuals and use of the F test to compare goodness of fit revealed that the average mIPSC decay was always best fitted with the sum of two exponential components. Thus, a weighted decay time constant (τw) was also calculated according to the equation:

where τ1 and τ2 are the decay time constants of the first and second exponential functions and P1 and P2 are the proportions of the synaptic current decay described by each component.

The mIPSC frequency was determined over 10 s bins for 2 min with the EDR program using a detection method based on the rate of rise of events (with a minimum rate of rise of 35–40 pA ms−1) and visual scrutiny. The tonic current was calculated as the difference between the holding current before and after application of bicuculline methobromide (30 μm; Belelli et al. 2005). We previously demonstrated the effects of bicuculline in this respect to be reproduced by 100 μm picrotoxin, a structurally distinct GABAA receptor antagonist (Belelli et al. 2005). In order to compare the efficacy of tonic and phasic inhibition per unit of time (s), the phasic charge was calculated by multiplying the individual mIPSC charge by the number of mIPSCs per second (effectively the frequency).

All results are reported as the arithmetic mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). Statistical significance of mean data was assessed with Student/s t test, paired or unpaired as appropriate, or byregular or repeated measures (RM) ANOVA followed post hoc by the Newman–Keul/s test as appropriate, using the SigmaStat software package (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). The large sample approximation of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) test (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to compare the distribution of individual mIPSC parameters. For a stringent comparison, the level of significance was set at P < 0.01 for KS tests.

Immunohistochemistry

All morphological experiments were performed on WT and α10/0 mice generated on a mixed C57BL/6J–129Sv/SvJ at the University of Pittsburgh (Vicini et al. 2001) and obtained from heterozygous (α1+/0) breeding pairs, or from first generation WT and α10/0 breeding pairs derived from α1+/0 mice. Four different sets of experiments were performed using the following antibodies: guinea pig antisera against GABAA receptor subunits α1, α2 and α3 and γ2 (raised in-house); rabbit antibodies against the α4 (PhosphoSolutions, Aurora, CO, USA; cat. no. 844-GA4N) and δ subunit (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA; cat. no. AB9752), vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT; Synaptic Systems, Göttingen, Germany, cat. no. 131003); mouse monoclonal antibody 7a against gephyrin (Synaptic Systems, cat. no. 147011). The characterization of antibodies was based on previous results (Kralic et al. 2006; Studer et al. 2006) and on the known regional and cellular expression pattern of their epitope.

Immunoperoxidase staining

The distribution of GABAA receptor subunits in the thalamus was compared in WT and α10/0 mice during postnatal development (P10, P20, P30, P60, n = 3 per age and genotype) in sections processed for immunoperoxidase staining. Mice were deeply anaesthetized with pentobarbital (Nembutal, 50 mg kg−1, i.p.) and transcardially perfused with a fixative containing 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% picric acid in 0.15 m phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. The brains were extracted immediately after the perfusion and postfixed in the same solution (P10, 24–36 h; P20, 12 h; P30 and adult, 4–6 h). Tissue was then processed for antigen retrieval as described (Kralic et al. 2006), cryoprotected with 30% sucrose in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and cut parasagitally at 40 μm from frozen tissue with a sliding microtome. Sections were collected in PBS and stored in antifreeze solution (15% glucose and 30% ethylene glycol in 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) prior to use.

Sections were incubated free-floating overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against GABAA receptor subunits (α1, 1 : 20 000; α2, α4, δ, affinity purified, 1–2 μg ml−1; α3, γ2, 1 : 3000) in Tris buffer containing 2% normal goat serum and 0.2% Triton X-100. Sections were then washed and incubated for 30 min at room temperature with biotinylated secondary antibodies (1 : 300; Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA, USA), followed by incubation in avidin–biotin complex (1 : 100 in Tris buffer) for 30 min (Vectastain Elite Kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), washed again and finally reacted with diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) in Tris buffer (pH 7.7) containing 0.015% hydrogen peroxide. The colour reaction was stopped after 5–15 min with ‘ice-cold’ PBS. Sections were then mounted on gelatin-coated slides and air-dried. Finally, they were dehydrated with ethanol, cleared in xylol, and coverslipped with Eukitt (Erne Chemie, Dällikon, Switzerland). Sections from WT and α10/0 mice were processed in parallel under identical conditions to minimize variability in staining intensity.

Immunofluorescence staining

Colocalization of GABAA receptor α1, α2, α4 and γ2 subunit with gephyrin at presumptive postsynaptic sites was analysed in WT and α10/0 mice using double immunofluorescence staining in sections prepared from fresh-frozen tissue. Mice (P10–12, P15, P20, P30; n = 3–5 per age and per genotype) were anaesthetized with isoflurane and decapitated, and the brain was extracted rapidly and frozen with powdered dry ice. Transverse sections were cut at 12 μm with a cryostat, mounted onto gelatin-coated glass slides, air dried at room temperature for 1 min, and stored at –20°C. They were then thawed at room temperature and fixed in methanol at −20°C for 2 min. After two washes in PBS, the sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with a mixture of primary antibodies diluted in PBS containing 4% normal goat serum. Sections were washed extensively in PBS and incubated for 30 min at room temperature with the corresponding secondary antibodies conjugated to Cy3 (1 : 500, Jackson Immunoresearch), or Alexa488 (1 : 1000, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA). Sections were washed again with PBS and coverslipped with mounting medium (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA, USA).

For covisualization of presynaptic terminals and gephyrin clusters in WT and α10/0 mice (P30, P60, n = 3 per age and genotype), tissue was prepared as described (Schneider Gasser et al. 2006). Mice were decapitated as above, the brain rapidly removed and placed in oxygenated ‘ice-cold’ artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF). Slices were prepared with a vibrating microtome and incubated for 20 min in aCSF at 34°C. They were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer for 10 min, extensively washed and incubated overnight in 30% sucrose in PBS for cryoprotection. Transverse sections (16 μm) were cut from frozen slices, mounted onto gelatin-coated slides, air dried at room temperature for 1 min, and stored at −20°C. They were then processed for double immunofluorescence staining with antibodies to VGAT (1 : 3000) and gephyrin (1 : 1000) as described above.

For quantification of GABA-ergic terminals in the VB of WT and α10/0 mice (P10, P30, P60, n = 3 per age and genotype), immunofluorescence staining was performed with anti-VGAT antibodies in perfusion-fixed tissue that was not processed for antigen retrieval (see immunoperoxidase staining, above). After overnight incubation in primary antibodies and washing, free-floating sections were incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated to Cy3 in Tris buffer containing 2% normal goat serum for 30 min at room temperature, washed and coverslipped with DAKO mounting medium.

Image analysis

Sections processed for immunoperoxidase staining were visualized with brightfield microscopy (Axioplan; Zeiss) using the mosaic software (Explora Nova, La Rochelle, France) for image acquisition. For each antibody, similar acquisition parameters were selected for WT and α10/0 animals. Images were cropped to the desired dimensions in Adobe Photoshop CS. Minimal adjustments of contrast and brightness were made to entire images, if needed.

Double-immunofluorescence staining was visualized by confocal microscopy (Zeiss LSM-510 Meta; Jena, Germany) using a 100× Plan-Apochromat objective (N.A. 1.4). The pinhole was set to 1 Airy unit for each channel and separate colour channels were acquired sequentially. The acquisition settings were adjusted to cover the entire dynamic range of the photomultipliers. For display, images were processed with the image-analysis program Imaris (Bitplane; Zurich, Switzerland). Images from both channels were overlaid (maximal intensity projection) and background was subtracted, when necessary. A low-pass ‘edge preserving’ filter was used for images displaying α1, α2, or VGAT staining.

Postsynaptic clustering of gephyrin and gephyrin–α subunit colocalization was quantified from single confocal sections (512 × 512 pixels) at a magnification of 90 nm pixel−1 in 8 bit grayscale images, using a threshold segmentation algorithm (minimal intensity, 90–130; size 0.08–0.8 μm2). From the gephyrin–α subunit colocalized images, all structures > 0.057 μm2 were counted, representing a minimum of 70% overlay of both channels to be considered as colocalized (ImageJ imaging software, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). The data were quantified in six sections per animal (n = 3 per genotype and age, Kruskal–Wallis followed by Dunn/s multiple comparison test; Prism, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

For quantification of the density of GABA-ergic presynaptic terminals, volumes were reconstructed from stacks of 13 confocal images (512 × 512 pixels) spaced by 0.25 μm at a magnification of 90 nm pixel−1. All files were blinded and individual terminals were identified as isolated objects with 1 μm3 minimal apparent volume and counted automatically (Imaris; Bitplane). Size distribution of VGAT positive terminals was analysed in single confocal sections (ImageJ imaging software). These data were quantified in six sections per animal (n = 3 per genotype and age, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test).

Results

Developmental changes in the properties of VB synaptic receptors

We investigated in detail the influence of development (P8–9; P10–11; P12–14; P15–22 and P23–27) of the mouse on the amplitude, decay and frequency of VB mIPSCs (Fig. 1; Table 1). In agreement with a previous study on rat VB neurones (Huntsman & Huguenard, 2000), these mIPSC parameters exhibited significant changes across the five developmental stages (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA; see Table 1). For P8–9 neurones the mIPSCs were of relatively large amplitude (−99 ± 4.0 pA; n = 33), decayed relatively slowly (τW= 9.0 ± 0.4 ms; n = 33) and occurred at a frequency of 8.5 ± 0.8 Hz (n = 33). However, within the next 24–48 h (P10–11) the mIPSC characteristics changed considerably. In particular, the mIPSC decay time (τW) decreased (5.4 ± 0.3 ms; n = 18, P < 0.05 versus P8–9, Newman–Keul/s test) and with subsequent development was further reduced (P12–14, 5.1 ± 0.3 ms, n = 24; P15–22, 3.9 ± 0.1 ms, n = 66; P23–27, 3.4 ± 0.2 ms, n = 18, all P < 0.05 versus P8–9). The change to the mIPSC decay that occurred between P8–9 and P10–11 was not accompanied by an alteration to the mIPSC amplitude (P8–9, −99 ± 4 pA, n = 33; P10–11, −96 ± 8 pA; n = 18, P > 0.05 versus P8–9). However, by P12–14 the mIPSC amplitude had decreased (−68 ± 3 pA; n = 24, P < 0.05 versus P8–9), but subsequently remained stable with further development (P15–22, −74 ± 2 pA, n = 66; P23–27, −79 ± 4 pA, n = 18, P > 0.05 versus P12–14). Hence, given the developmental changes to amplitude and duration, the charge passed by each mIPSC was significantly greater at P8–9 (897 ± 46 fC; n = 33), than for later time points (e.g. P23–27, 287 ± 20 fC, n = 18, P < 0.05). The frequency of mIPSCs increased significantly throughout the developmental period (e.g. P8–9, 8.5 ± 0.8 Hz, n = 33; P15–22, 26 ± 2.6 Hz, n = 66; P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA), with this effect becoming significantly different from P8–9 by P15–22 (Fig. 1, Table 1). Although the phasic charge per event is significantly reduced with development, the increase in mIPSC frequency with maturation results in the total phasic charge per second not being significantly changed during the developmental period studied here (P > 0.05, one-way ANOVA, Table 1).

Figure 1. The properties of mIPSCs recorded from VB neurones of WT mice are developmentally regulated.

A, superimposed ensemble averages of mIPSCs recorded from exemplar VB neurones of WT mice at five different developmental stages (P8–9, P10–11, P12–14, P15–22 and P23–27). The traces illustrate the changes to peak amplitude (left panel) and synaptic current decay (right panel) that occur with development. In the right-hand panel, all traces are normalized to the peak amplitude of the exemplar P23–27 recording to highlight the change to the mIPSC decay that occurs with maturation. B, combined cumulative probability plots of the peak amplitude (left panel) and of the time required for individual mIPSCs to decay from peak amplitude to 10% of peak (T90, right panel). The plots are constructed from peak amplitude and T90 values obtained from 945 to 2142 mIPSCs collected from 10 representative neurones for each of the five age groups investigated. Note the progressive leftward shift of both the peak amplitude and T90 values with development (P < 0.01; KS test), although the changes to amplitude and kinetics are not synchronous. C, bar graph illustrating the increase of VB mIPSC frequency with development. Data were obtained from 18–66 cells. Error bars indicate the s.e.m.D, recordings obtained from exemplar WT VB neurones for the P8–9 (top trace) and P23–27 (bottom trace) age groups illustrating the increase of mIPSC frequency with development (*P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA).

Table 1.

Summary of the developmental changes (P8–27) to GABAA receptor-mediated phasic and tonic transmission of wild type VB neurones

| P8-9 | P10-11 | P12-14 | P15-22 | P23-27 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mIPSC amplitude (pA) | 99 ± 4 (n = 33) | 96 ± 8 (n = 18) | 68 ± 3 (n = 24) | 74 ± 2 (n = 66) | 79 ± 4 (n = 18) |

| mIPSC τw (ms) | 9 ± 0.4 | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 5.1 ± 0.3 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 3.4 ± 0.2 |

| mIPSC charge transfer (−fC) | 897 ± 46 | 533 ± 53 | 351 ± 24 | 295 ± 12 | 287 ± 20 |

| mIPSC frequency (Hz) | 8.5 ± 0.8 | 15.6 ± 2.0 | 15.4 ± 1.7 | 26.0 ± 2.6 | 24.0 ± 4.7 (n = 16) |

| Total phasic charge (−fC) | 7389 ± 789 | 8070 ± 1346 | 5129 ± 576 | 8159 ± 1013 | 7000 ± 1384 |

| Tonic current (−pA) | 23 ± 6 (n = 11) | 30 ± 9 (n = 7) | 37 ± 6 (n = 8) | 74 ± 8 (n = 25) | 93 ± 15 (n = 9) |

| Tonic charge (−fC) | 23 198 ± 6003 | 30 416 ± 8894 | 36 509 ± 6446 | 74 174 ± 8400 | 93 304 ± 14,822 |

| Total charge (−fC) | 28 264 ± 5499* | 38 238 ± 9,562* | 41 499 ± 6828* | 79 309 ± 8492* | 98 177 ± 14,779* |

| THIP-induced current (−pA) | 80 ± 23 (n = 6) | ND | ND | 293 ± 34 (n = 7) | 337 ± 18 (n = 4) |

| Nipecotic acid-induced current (−pA) | 105 ± 31 (n = 6) | ND | ND | 415 ± 88 (n = 5) | ND |

| Tonic/total charge (%) | 73 ± 8* | 76 ± 5* | 87 ± 3* | 92 ± 1* | 94 ± 1* |

Note that all individual mIPSC properties (peak amplitude, τw, charge transfer and frequency), amplitude of the tonic current together with the relative contribution (%) of the tonic to the total charge and the THIP-induced current are significantly different across the different developmental stages investigated here (P < 0.05, ANOVA). Similarly, the nipecotic-induced current is significantly greater at P15–22 than at P8–9 (P > 0.001 unpaired t test). The total phasic charge does not exhibit significant changes across development (P > 0.05, ANOVA). ND, not determined

values derived only from the sample of cells for which a paired (i.e. matched from the same cell) estimation of the phasic and tonic charge was performed.

By contrast, the amplitude of mIPSCs recorded from mouse nRT neurones was little influenced by the developmental stage of the animal (P8–9, −67 ± 6 pA, n = 8; P15–22, −64 ± 3 pA, n = 21; P > 0.05, unpaired Student/s t test). However, early in development the decay of nRT mIPSCs was significantly slower (P8–9, 21.4 ± 0.7 ms, n = 8; P15–22, 15.8 ± 0.9 ms, n = 21; P < 0.001; unpaired t test).

The α1 subunit is expressed synaptically in P15–22 VB neurones

The relatively fast mIPSC decay ≥ P15 is consistent with the synaptic expression of the α1 subunit, a view supported by both immunohistochemistry and electrophysiological studies with zolpidem (Belelli et al. 2005; Kralic et al. 2006). However, although low nanomolar concentrations of zolpidem are selective for receptors containing both α1 and γ2 subunits, higher concentrations enhance the function of the equivalent receptors incorporating α2, or α3 subunits (Rudolph & Mohler, 2006). Therefore, to confirm that synaptic GABAA receptors of P15–22 VB neurones contain the α1 subunit, we utilized the α1H101R‘knock-in’ mouse (McKernan et al. 2000). Receptors incorporating this mutant α1 subunit are insensitive to diazepam and zolpidem (Rudolph & Mohler, 2006). The mIPSCs (amplitude =−74 ± 4 pA; τW= 3.7 ± 0.2 ms, n = 29, P > 0.05 versus WT, unpaired t test) recorded from VB neurones of P15–22 α1H101R mice were indistinguishable from their WT counterparts, demonstrating that this genetic manipulation does not influence GABAA receptor expression, or function in these neurones (Fig. 2A). A concentration (100 nm) of zolpidem that should be relatively selective for α1 subunit containing receptors and that produced a clear prolongation of WT mIPSCs, was ineffective for VB mIPSCs of α1H101R mice (10 ± 4% increase, n = 6, P > 0.05; cf. WT 57 ± 7% increase, n = 6, P < 0.001; one-way RM ANOVA, Figs 2A and B), although, at the less selective concentration of 1 μm, zolpidem did produce a modest, yet significant prolongation of the VB mIPSC decay (α1H101R, 20 ± 4% increase of τw, n = 6; WT, 73 ± 14% increase, n = 6; P < 0.01 for both strains, one-way RM ANOVA Fig. 2B). However, the effect of 1 μm zolpidem on the mIPSC τW of VB neurones of WT mice was significantly greater than that for α1H101R mice (P < 0.001, two-way RM ANOVA).

Figure 2. The selective synaptic expression of the GABAA receptor α1 subunit in P15–22 VB neurones.

A, superimposed ensemble averages of VB mIPSCs recorded in the absence (black traces) and presence of the α1 subunit selective imidazopyridine, zolpidem (100 nm, grey traces) from exemplar WT (Aa) and α1H101R (Ab) neurones. Note that zolpidem prolongs the decay of WT mIPSCs, but not those recorded from α1H101R mice, consistent with the synaptic expression of the α1 subunit. B, summary bar graph illustrating the effects of zolpidem (100 nm, 1 μm) and Ro15-4513 (10 μm) upon the decay (τw, expressed as percentage change) of mIPSCs recorded from VB neurones of WT (black bars) and α1H101R (open bars) mice. Also illustrated are the effects of the α3 selective ligand, TP003 (100 nm), upon the decay of mIPSCs recorded from WT nRT (grey bar) and VB (black bar) neurones. C, superimposed representative mIPSC averages recorded from exemplar WT (black traces) and α10/0 (grey traces) nRT (Ca) and VB (Cb) neurones. Deletion of the α1 subunit causes a clear reduction in VB mIPSC frequency (not shown) and a decrease in amplitude of the remaining synaptic currents. Note that the majority (32/44 neurones, i.e. 73%) of P15–22 α10/0 neurones were silent and no mIPSCs were evident for P23–27 α10/0 neurones (16 cells tested). By contrast, deletion of the α1 subunit had no significant effect on the mIPSCs recorded from nRT neurones. Data were obtained from 3–6 cells. Asterisks in B indicate statistical differences (*P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001). Error bars indicate s.e.m.

The anxiolytic TP003 is functionally selective for recombinant receptors containing γ2 and α3 subunits compared with the equivalent receptors incorporating the α1 subunit (Dias et al. 2005). TP003 (100 nm) prolonged the decay of mIPSCs recorded from WT nRT neurones (44 ± 12% increase, n = 6, P < 0.05, one-way RM ANOVA), but was significantly less effective in prolonging the decay of WT VB mIPSCs (20 ± 4% increase, n = 5, P < 0.05 versus WT, two-way RM ANOVA; see Fig. 2B). Hence, collectively these data are consistent with VB neurones expressing synaptic GABAA receptors incorporating the α1 subunit, although at this age (P15–22), there may be minor populations of receptors incorporating α2 or α3 subunits.

In VB neurones the α4 subunit is mainly associated with the δ subunit and located extrasynaptically (Sur et al. 1999; Peng et al. 2002; Chandra et al. 2006; Kralic et al. 2006). However, in thalamus, immunoprecipitation studies suggest an additional coassembly of the α4 and γ2 subunits (Sur et al. 1999). To determine whether synaptic currents in WT VB neurones are mediated in part by receptors incorporating both α4 and γ2 subunits, we made use of the pharmacological profile of Ro15-4513. This ligand acts as a partial agonist of recombinant receptors incorporating these subunits, whereas it displays inverse agonist action at equivalent receptors containing α1, α2, α3, or α5 subunits (Benson et al. 1998). Consistent with synaptic receptors containing α1 and γ2 subunits Ro15-4513 (10 μm) produced a modest acceleration of the mIPSC decay (14 ± 2% decrease of τW, n = 3, P < 0.05, one-way RM ANOVA see Fig. 2B) in WT VB neurones. Furthermore, it significantly prolonged the mIPSC decay of α1H101R VB neurones (30 ± 6% increase of τW, n = 5, P < 0.01, one-way RM ANOVA; Fig. 2B), in line with its partial agonist effect of receptors containing an arginine residue in position 101. The contrasting effects of Ro15-4513 on the phasic currents of WT and α1H101R VB neurones further confirms the expression of synaptic α1 and γ2 subunits, and additionally suggests that synaptic receptors incorporating α4 and γ2 subunits are not expressed in these P15–22 VB neurones.

The expression of the α1 subunit in VB neurones is developmentally regulated: studies with the α10/0 mouse

In agreement with the conclusions above, deletion of the α1 subunit greatly compromised inhibitory synaptic transmission in P23–27 VB neurones, with none of the cells sampled (n = 16) exhibiting mIPSCs (Fig. 3). In stark contrast, for P8–9 and P10–11 VB neurones, this genetic manipulation had no significant effect on the frequency, amplitude, or kinetics of mIPSCs when compared with aged matched WT controls (P > 0.05, unpaired t test Figs 3 and 4, Tables 1 and 2), suggesting the synaptic incorporation of the α1 subunit occurs during neuronal maturation. This transition develops during the second and third postnatal week as 18% (4 of 22) of P12–14 and 73% (32 of 44) of P15–22 VB neurones sampled from α10/0 mice were devoid of mIPSCs (Fig. 3, Tables 1 and 2). The specificity of the mutation for VB neurones was substantiated by recording mIPSCs of nRT neurones from α10/0 mice, which were indistinguishable from their WT counterparts (Fig. 2C). Synaptic GABAA receptors of ≥ P16 VB neurones incorporate a β2 subunit (Belelli et al. 2005). However, mirroring the results with the α10/0 mice, in younger neurones, deletion of the β2 subunit had no significant effect on VB mIPSCs (frequency = 9.8 ± 1 Hz; amplitude =−83 ± 6 pA; τW= 7.9 ± 0.5 ms, n = 12, P > 0.05 versus WT, unpaired t test). Collectively, these results suggest during maturation the synchronized synthesis of both α1 and β2 subunits to form synaptic α1β2γ2 receptors.

Figure 3. GABAA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission is disrupted by deletion of the α1 subunit, but only later in development.

Recordings obtained from exemplar WT (left-hand column) and α10/0 (right-hand column) VB neurones for five different age groups. Early in development (P8–11) mIPSCs recorded from VB neurones of α10/0 mice are indistinguishable from those of WT. However, beyond P14, the majority of VB neurones from α10/0 mice are devoid of mIPSCs. The proportion of recorded cells displaying synaptic currents is stated below each exemplar trace.

Figure 4. The developmental change (P8–14) to mIPSC amplitude and decay do not require the GABAAα1 subunit.

A, representative superimposed averages of mIPSCs recorded from exemplar WT (black traces) and α10/0 (grey traces) VB neurones of P8–9, P10–11 and P12–14 mice. Note that, even in the absence of the α1 subunit, the mIPSC decay shortens at P10–11 and P12–14 compared with P8–9. B, a combined cumulative probability plot of the mIPSC T90 values obtained from 774–2142 events collected from 10 representative VB neurones of WT and α10/0 VB neurones at P8–9 and P12–14 (black curves, WT; grey curves, α10/0). The leftward shift in T90 values observed in VB neurones of P12–14 α10/0 mice indicates that synaptic expression of the α1 subunit is not a prerequisite for the shortening of the mIPSC decay that occurs in the second postnatal week. C and D, graphs illustrating the influence of development (P8–27) on the τW (C) and the peak amplitude (D) of mIPSCs recorded from VB neurones of WT (▪) and α10/0 (▵) mice. X-axis values are presented as the mean age of each developmental group studied. Data were obtained from 18–66 cells. E, summary bar graph illustrating the effects of zolpidem (100 nm, 1 μm) and Ro15-4513 (10 μm) upon the decay (τw, expressed as percentage change) of mIPSCs recorded from VB neurones of WT (black bars), α1H101R (open bars), α2H101R (dark grey bars) and α10/0 (light grey bars) mice. Data were obtained from 4–7 neurones. Error bars indicate s.e.m. Note that for the different developmental stages the standard error associated with each age group is also illustrated in C and D.

Table 2.

Summary of the developmental changes (P8–27) to GABAA receptor-mediated phasic and tonic transmission of α10/0 VB neurones

| P8-9 | P10-11 | P12-14† | P15-22§ | P23-27‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mIPSC amplitude (−pA) | 99 ± 4 (n = 21) | 79 ± 5 (n = 10) | 67 ± 6 (n = 18) | 36 ± 4 (n = 12) | ND |

| mIPSC τw (ms) | 8.7 ± 0.3 | 5.5 ± 0.2 | 5.6 ± 0.3 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | ND |

| mIPSC charge transfer (−fC) | 826 ± 49 | 439 ± 30 | 420 ± 50 | 194 ± 38 | ND |

| mIPSC frequency (Hz) | 7.5 ± 1.0 | 9.5 ± 2.2 | 10.6 ± 1.3 | 14.0 ± 2.8 | ND |

| Total phasic charge (−fC) | 6084 ± 908 | 4218 ± 1028 | 4849 ± 890 | 2033 ± 308 | ND |

| Tonic current (−pA) | 28 ± 8 (n = 11) | ND | ND | 55 ± 7 (n = 21) | ND |

| Tonic charge (−fC) | 27 674 ± 7670 | ND | ND | 54 974 ± 7241 | ND |

| Total charge (−fC) | 33 390 ± 8288* | ND | ND | 55 470 ± 7304** | ND |

| Tonic/total charge (%) | 76 ± 7* | ND | ND | 99 ± 0.4** | ND |

Not including the 32 cells of 44 cells tested (73%) that were silent.

Not including the 4 cells of the 22 cells tested (18%) that were silent (note the 4 silent cells were all derived from day 14 animals).

No mIPSCs in all (16) cells tested. ND, not determined.

Values derived only from the sample of cells (n = 11) for which a paired (i.e. matched from the same cell) estimation of the phasic and tonic charge was performed.

Value derived from all the cells (n = 21) exhibiting a tonic conductance including those without any detectable mIPSCs. Note that the tonic contribution to the total charge was significantly greater at P15-22versusP8-9 (P > 0.05).

Does expression of the α1 subunit produce the developmental change in mIPSC kinetics of VB neurones?

As described above, the mIPSC decay time reduces with development. Receptors incorporating the α1 subunit are reported to have relatively fast kinetics compared with equivalent receptors containing the α2 or α3 subunit and are implicated in the appearance of rapidly decaying mIPSCs in developing CGCs and cortical neurones (Goldstein et al. 2002; Ortinski et al. 2004; Bosman et al. 2005; Belelli et al. 2006). Hence, given the differential impact of deleting the α1 subunit on mIPSCs at P8–9 and P15–22, the change in mIPSC kinetics may be due to the increased expression of the α1 subunit with development. Here, the mIPSC τW of VB neurones decreased substantially within a 24–48 h period between P8–9 and P10–11 (Table 1; Fig. 1). For WT P8–9 neurones, a non-selective concentration (1 μm) of zolpidem prolonged the decay of mIPSCs (τW= 44 ± 4% increase, n = 7, P < 0.05, one-way RM ANOVA), an effect significantly reduced for equivalent recordings made from P8–9 neurones derived from α2H101R mice (τW= 16 ± 6% increase, n = 5, P < 0.001 versus WT, two-way RM ANOVA; Fig. 4E). These results confirm the presence of synaptic receptors containing the α2 and γ2 subunit at this developmental stage.

Should the increased expression of the α1 subunit cause the change to the mIPSC kinetics that occurs within 24–48 h at P10–11, then deletion of the α1 subunit (in common with P15–22 neurones) would have a substantial effect on the VB mIPSCs (cf. P8–9 synapses which mainly incorporate α2-GABAA receptors). However, surprisingly mIPSCs were evident in all (n = 10) P10–11 VB neurones of α10/0 mice tested (Figs 3 and 4). In these α10/0 neurones neither the mIPSC amplitude (79 ± 5 pA) nor the frequency (9.5 ± 2.2 Hz) was significantly different from WT age matched controls (P > 0.05, unpaired t test; Fig. 4, Tables 1 and 2). Importantly, at this developmental stage mIPSCs recorded from α10/0 VB neurones exhibited a similarly rapid decay (τW= 5.5 ± 0.2 ms, n = 10) to WT mIPSCs (τW= 5.4 ± 0.3 ms, n = 18, P > 0.05, unpaired t test; see Fig. 4C, Tables 1 and 2). Furthermore, even by P12–14, mIPSCs were still evident in the majority of α10/0 VB neurones (82%, i.e. 18 out of 22 cells tested – note the 4 ‘silent’ cells were from P14 mice; see Fig. 3). Such mIPSCs were of a similar amplitude (α10/0, 67 ± 6 pA, n = 18; WT, 68 ± 3 pA, n = 24; P > 0.05, unpaired t test) and time course (α10/0: τW= 5.6 ± 0.3 ms, n = 18; WT: τW= 5.1 ± 0.3 ms, n = 24; P > 0.05, unpaired t test) to their WT counterparts (Fig. 4A–C). By P15–22 the majority of α10/0 VB neurones were ‘silent’ (only 12 cells exhibited mIPSCs from 44 neurones tested). For those neurones exhibiting mIPSCs, the events were of reduced amplitude (α10/0, 36 ± 3.7 pA, n = 12; WT, 74 ± 2.5 pA, n = 66; P < 0.001, unpaired t test; see Figs 2C and 4D). The mean mIPSC frequency, although reduced, was not significantly different from that of WT neurones (α10/0, 14 ± 2.8 Hz, n = 12; WT, 26 ± 2.6 Hz, n = 63; P > 0.05, unpaired t test – note this does not take into account the majority of α10/0 VB neurones which were ‘silent’). Hence, the disappearance of synaptic GABAA receptors from the VB neurones of α10/0 mice does not occur in an ‘all or nothing’ manner.

As described above, 100 nm zolpidem produced a substantial prolongation of mIPSCs recorded from WT but not α1H101R VB P15–22 neurones. However, this concentration of the α1 subunit selective ligand had little effect on the decay of mIPSCs of P10–11 neurones derived from either WT or α1H101R mice (WT, 5 ± 2%, P > 0.05; α1H101R, 9 ± 4%, P > 0.05; one-way RM ANOVA; WT versusα1H101R, P > 0.05, two-way RM ANOVA, Fig. 4E). Therefore, although compensatory changes may occur as a consequence of the deletion of the α1 subunit, importantly the collective results of these experiments clearly establish that the developmental change to mIPSC kinetics can occur in the absence of the α1 subunit. However, it is conceivable that the subsequent further decrease of the mIPSC decay that occurs post P12 (Tables 1 and 2) may be due to the synaptic incorporation of the α1 subunit. Indeed, the decay of the remaining mIPSCs of P15–22 α10/0 neurones (presumably mediated by residual α2-GABAA receptors) was significantly prolonged, compared to their WT counterparts (α10/0τW= 4.8 ± 0.4 ms, n = 12; WT τW= 3.9 ± 0.1 ms; n = 66; P < 0.01, unpaired t test).

Theoretically the fast mIPSCs evident for P10–11 neurones could be mediated by synaptic receptors incorporating the α4 subunit as it is expressed in VB neurones and recombinant receptors containing α4 and γ2 subunits are known to be associated with relatively rapid kinetics (Lagrange et al. 2007; Picton & Fisher, 2007). As described above, Ro15-4513 acts as a positive allosteric modulator of receptors incorporating α4 and γ2 subunits and a partial inverse agonist of the equivalent receptors incorporating α1–3, or α5 subunits. However, this compound did not prolong but produced a modest shortening of the mIPSC decay of both WT and α10/0 VB P10–11 neurones, with no significant differences between genotypes (WT = 24 ± 3% decrease, P < 0.01; α10/0= 18 ± 5% decrease, P < 0.05, one-way RM ANOVA; WT versusα10/0P > 0.05, two-way RM ANOVA; Fig. 4E). Hence, it is unlikely that the brief mIPSCs, characteristic of this developmental stage are mediated by α4-GABAA receptors.

Developmental changes in the properties of VB extrasynaptic receptors

We have previously reported the presence of a large ‘tonic’ current in P16–24 mouse VB neurones, which is mediated by extrasynaptic GABAA receptors (Belelli et al. 2005). Given the changes to the synaptic GABAA receptors of VB neurones, we investigated whether their extrasynaptic receptors were similarly subject to developmental plasticity. Such extrasynaptic receptors contain the δ subunit (Porcello et al. 2003) and in the rat thalamus, early in postnatal development, the δ subunit mRNA levels are relatively low (Laurie et al. 1992). In agreement, application of bicuculline (30 μm) to P8–9 neurones produced an outward current of only 23 ± 6 pA (n = 11; see Fig. 5A, Table 1), a response considerably less than that reported for P16–24 neurones (Belelli et al. 2005). We therefore determined the tonic current at different developmental stages (Fig. 5, Table 1). The tonic current amplitude exhibited significant changes across the five developmental stages (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA; see Table 1). Thus, although the magnitude of the tonic current was modestly augmented at P10–11 and at P12–14 (30 ± 9 pA, n = 7; 37 ± 6 pA, n = 8, respectively; P > 0.05 versus P8–9 for either age group) it then increased substantially (P15–22, 74 ± 8 pA, n = 25; P23–27, 93 ± 15 pA, n = 9; P < 0.005 versus P8–9 for both age groups; Fig. 5), i.e. from P8–9 to P23–27 the tonic current increased in magnitude by ∼4 fold. The relatively small tonic current at P8–9 may be a consequence of a variety of factors including changes to neuronal size, limited expression of extrasynaptic receptors, or perturbations to the local ambient GABA concentration.

Figure 5. The tonic current of VB neurones increases with development.

A, left panels, whole-cell recordings obtained from VB neurones of WT mice at P8–9 (Aa), P12–14 (Ab) and P23–27 (Ac). Right panels, the corresponding all-points histograms, normalized to the holding current recorded in the presence of bicuculline. Application of 30 μm bicuculline (grey) reveals a GABAA receptor-mediated tonic current, which increases in magnitude with development. B, a graph illustrating the developmental changes in mIPSC τw (left axis) and mIPSC peak, or tonic current amplitudes (right axis). X-axis values are presented as the mean age of each group studied. Note that the most dramatic changes to τw, peak amplitude and the magnitude of the tonic current occur at different developmental stages. Data were obtained from 18–66 cells for the mIPSCs and 7–25 cells for the tonic currents. Error bars indicate the s.e.m. Note that for the different developmental stages, the standard error associated with each age group is also illustrated in B.

The whole-cell capacitance of VB neurones did not change with development (P > 0.05, one-way ANOVA), suggesting little difference in the overall size of the neuronal cell soma (see Methods) and consequently the current density increases with maturation. For example, when normalized to whole-cell capacitance the tonic conductance of P8–9 VB neurones (16 ± 3.9 pS pF−1, n = 11) was significantly less (P < 0.001 unpaired t test) than that of P23–27 neurones (59 ± 9.0 pS pF−1; n = 9). However, our conclusion presumes all of the measured ‘tonic’ current to emanate from the cell body.

In the thalamus, THIP acts as a selective ligand for thalamocortical extrasynaptic GABAA receptors (Belelli et al. 2005; Cope et al. 2005; Jia et al. 2005; Chandra et al. 2006). As observed for the tonic current, the magnitude of the current induced by 1 μm THIP also increased significantly (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA) with development (P8–9, –80 ± 23 pA; P15–22, –293 ± 34 pA; P23–27, –337 ± 18 pA; n = 4–7; see Fig. 6A and C, Table 1). However, relating these responses to their corresponding tonic current (i.e. induced by bicuculline alone) the THIP-induced current was ∼3.5-fold that of the corresponding tonic current at both P8–9 and P23–27.

Figure 6. An increase in extrasynaptic receptor expression primarily accounts for the developmental increase of the tonic conductance of VB neurones.

A, the selective extrasynaptic GABAA receptor agonist THIP (gaboxadol, 1 μm) increases the magnitude of the tonic current in exemplar VB neurones of both P8–9 (Aa) and P15–22 (Ab) WT mice. However, note that the effect of the agonist is much greater for neurones from the older age group. B, the non-selective GAT inhibitor nipecotic acid (1 mm) increases the tonic current amplitude in exemplar VB neurones of both P8–9 (Ba) and P15–22 (Bb) WT mice. In common with THIP, the effect of nipecotic acid is greater for P15–22 than for P8–9 neurones. C, bar graph summarizing the change in holding current in response to the bath application of bicuculline (30 μm), THIP (1 μm) and nipecotic acid (1 mm) to WT VB neurones of P8–9 (open bars), P15–22 (black bars) and P23–27 (grey bars) mice. Data were obtained from 4 to 25 cells. Error bars indicate s.e.m.

In cerebellum, cerebral cortex and hippocampus, GABA transporters (GATs) influence both phasic and tonic inhibition (Nusser & Mody, 2002; Ortinski et al. 2006). Four GABA transporters have been identified and they are differentially distributed in the CNS (Conti et al. 2004). For P8–9 and P15–22 neurones the non-selective GAT inhibitor nipecotic acid (1 mm) induced an inward current of −105 ± 31 pA (n = 6) and −415 ± 88 pA (n = 5), respectively (P > 0.001, P15–22 versus P8–9, unpaired t test; see Fig. 6B and C, Table 1). Relating these responses to their corresponding tonic current demonstrated that nipecotic acid increased the tonic current by ∼4.6- and 5.6-fold for P8–9 and P15–22 neurones, respectively.

Collectively, the experiments with THIP and nipecotic acid suggest that the developmental increase in the tonic conductance is primarily a consequence of an increase in extrasynaptic receptor expression.

α1-GABAA receptors do not contribute to the tonic current of P15–22 VB neurones

Although in older neurones phasic inhibitory synaptic transmission was greatly compromised by deletion of the α1 subunit, recordings from such VB α10/0 neurones revealed the characteristic membrane noise evident for WT neurones, suggesting the presence of a ‘tonic’ conductance (Fig. 7). In confirmation, bicuculline (30 μm) induced an outward current (55 ± 7 pA, n = 21) for P15–22 α10/0 VB neurones that was not significantly different from WT neurones (P > 0.05, unpaired t test; see Fig. 7). These data reveal that synaptic GABAA receptors of VB neurones can be eliminated by the deletion of the α1 subunit, with little or no apparent perturbation of extrasynaptic GABAA receptor expression. This conclusion agrees with the finding that ‘tonic inhibition’ of VB neurones is abolished by deletion of the α4 subunit (Chandra et al. 2006), suggesting little or no contribution of α1-GABAA receptors to the tonic current.

Figure 7. Deletion of the α1 subunit does not influence the tonic current of VB neurones.

A, a whole-cell recording from an exemplar α10/0 VB neurone. In common with WT VB neurones, the application of bicuculline reveals a large tonic conductance. Note the absence of synaptic currents under control conditions prior to bicuculline application. B, bar graph illustrating the magnitude of the tonic current in VB neurones of WT (black bar), α1H101R (grey bar), α10/0 (light grey bar) and β20/0 (open bar). Note that the tonic current recorded from β20/0, but not α1H101R or α10/0, VB neurones is significantly different from WT. The data for the β20/0 neurones are reproduced from Belelli et al. (2005) and are shown here for comparison. Data were obtained from 7–25 recordings. Asterisks in B indicate statistical differences (***P < 0.001). Error bars indicate s.e.m.

Unaltered developmental maturation of the α2 subunit in VB of α10/0 mice

Immunohistochemistry for GABAA receptor subunits was used to complement the analysis of the developmental changes in the properties of synaptic GABAA receptors in VB neurones. Mirroring electrophysiological findings, delayed expression of the α1 was observed in WT mice. While being almost undetectable at P10, α1 subunit immunoreactivity became prominent at P20 (Fig. 8A and G). In parallel, α2 subunit staining was very strong at birth (not shown) and decreased gradually to disappear between P10 and P20 (Fig. 8B and H). These changes are in striking contrast to the α3 subunit-immunoreactivity, which selectively labelled the nRT and remained rather constant throughout postnatal development (Fig. 8C and I). In α10/0 mice, the developmental maturation of the α2 and α3 subunit was the same as in WT (Fig. 8, middle and right column), and the absence of the α1 subunit was not compensated for by these subunits. These observations are in line with the complete loss of synaptic GABAA receptor-mediated currents in VB neurones of α10/0 mice.

Figure 8. Comparative distribution of α1 (A, G, J), α2 (B, E, H, K) and α3 (C, F, I, L) subunit immunoreactivity in the thalamus at P10 (A–C, E, F) and P20 (G–L) in WT (A–C, G–I) and α10/0 (E, F, J–L) mice.

Parasagittal sections were processed for immunoperoxidase staining. A schematic drawing of the regions depicted is given in D. The α1 subunit is conspicuously absent in VB (VPL + VPM) of P10 WT mice, but increases rapidly thereafter. In contrast, the α2 subunit staining is moderate at P10 and decreases to background levels by P20 in both WT and α10/0 mice. Finally, the α3 subunit immunoreactivity, which is intense in Rt in both genotypes, is not detectable in VB at either age. Abbreviations: APT, anterior pretectal nucleus; fi, fimbria of the hippocampus; ic, internal capsule; LD, laterodorsal thalamic nucleus; Po, posterior thalamic nuclear group; Rt, reticular thalamic nucleus; st, stria terminalis; VPL; ventral posterolateral thalamic nucleus; VPM, ventral posteromedial thalamic nucleus; ZID, zona incerta, dorsal part; ZIV, zona incerta, ventral part. Scale bars, 100 μm (scale bar in F applies to A–F, scale bar in L applies to G–L).

Synaptic GABAA receptors are associated with gephyrin

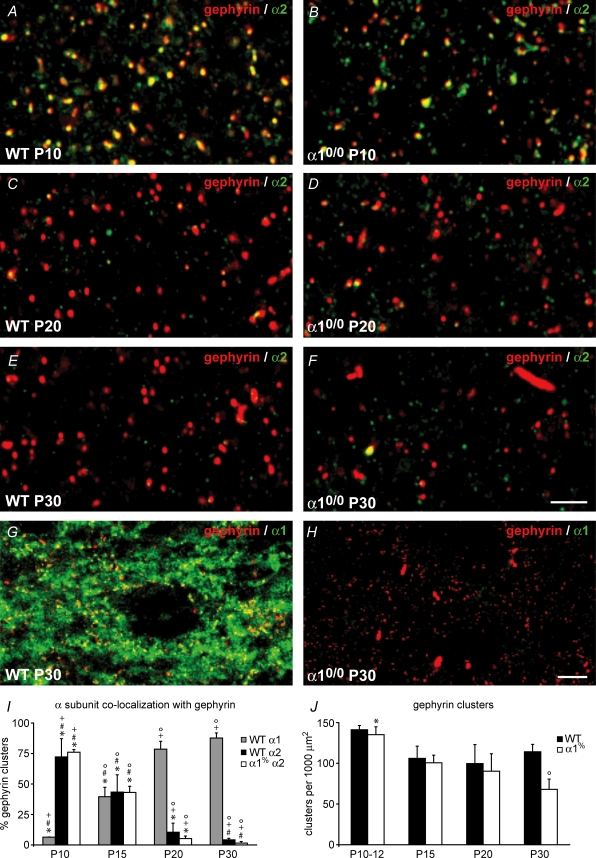

Gephyrin is a marker of GABA-ergic and glycinergic postsynaptic sites in the CNS, forming clusters that are selectively colocalized with GABAA receptor subunits, as seen by immunofluorescence staining (Sassoè-Pognetto et al. 2000; Kralic et al. 2006). A systematic analysis of gephyrin clusters and their colocalization with the α1 and α2 subunit was therefore conducted between P10 and P30 in the VB of both WT and α10/0 mice. At P10, a high density of gephyrin clusters was evident, with almost 80% of them being colocalized with the α2 subunit in both genotypes and less than 10% with the α1 subunit in WT (Fig. 9A, B and I). The density of gephyrin clusters was the same in sections from mutant and WT (Fig. 9J). The incidence of colocalization between gephyrin clusters and the α2 subunit decreased gradually by about 10% per day to become negligible at P20 (Fig. 9A–F and I, P < 0.05 in both genotypes, Kruskal–Wallis test), reflecting the gradual disappearance of the α2 subunit immunoreactivity and the loss of synaptic GABA-ergic currents recorded in neurones from mutant mice (Fig. 3). In WT neurones, colocalization with the α1 subunit was around 40% at P12–P15 and abruptly increased to almost 100% at P20 (Figs 9I, P < 0.05, Kruskal–Wallis test). We could not determine whether α1-GABAA receptors replace α2-GABAA receptors at the same synaptic sites, or whether the switch in subunit expression reflects the formation of novel synapses. However, the conservation of gephyrin clusters in VB neurones from α10/0 mice, most likely devoid of associated GABAA receptors, favours the first alternative.

Figure 9. Differential alterations in postsynaptic clustering of the α2 (green; A–F) and α1 subunit (green; G–H) and gephyrin (red, A–H) during development of WT (left column) and α10/0 (right column) mice, visualized by immunofluorescence staining and confocal laser scanning microscopy.

At P10 (A and B) most gephyrin clusters are colocalized with the α2 subunit in both genotypes. This fraction gradually decreases between P10 and P30 (A–F, quantified in I), due to the loss of α2 subunit staining, which is replaced by the α1 subunit in WT (G, quantified in I), but not in mutants (H). As a result, gephyrin clusters in α10/0 mice remain isolated, and at P30, gephyrin forms large aggregates (F and H). I, quantification of colocalization patterns between gephyrin and the α1 or α2 subunit in WT and α10/0 mice. Pair-wise significant differences between age groups are indicated by symbols (*P < 0.05 compared to P30; #P < 0.05 compared to P20; +P < 0.05 compared to P15; °P < 0.05 compared to P10). J, quantification of gephyrin cluster density in WT and α10/0 mice. No change is evident in WT, whereas a 30% decrease occurs in mutants between P10 and P30; the same symbols are used as in I. Scale bar in F, 3 μm (applies to A–F), in H, 10 μm (applies to G and H).

Delayed alteration of gephyrin clustering in VB neurones of α10/0 mice

Between P10 and P30, there was a significant reduction in gephyrin cluster density with increasing age in WT and α10/0 animals (P < 0.01 in both genotypes, Kruskal–Wallis test), reflecting the growth of the VB (Fig. 9J). At P30, the density of gephyrin clusters in WT mice was 20% lower than at P10 (n.s.), whereas in α10/0 mice the reduction reached 50% (P < 0.05), reflecting the absence of association with the α1 subunit. Instead, large, presumably intracellular, aggregates became apparent, as previously described in sections from adult mice (Kralic et al. 2006). This trend continued at later stages, with gephyrin clusters being replaced by large intracellular aggregates until about P60. At this age, no gephyrin clusters remained in the VB of mutant mice. In view of the complete absence of mIPSCs in VB neurones from mutant mice at P23 and later, we interpret this trend as evidence for impaired gephyrin postsynaptic clustering in the absence of associated GABAA receptors.

At the subcellular level, the α2 subunit immunoreactivity in sections from P10 and P20 mice was punctate, forming clusters extensively colocalized with gephyrin (Fig. 9A–D). In contrast, the α1 subunit staining was diffuse in the neuropil, outlining the cell body of individual VB neurones (Fig. 9G). Although most gephyrin clusters were double-labelled for the α1 subunit, the majority of α1 subunit staining was not associated with gephyrin. While such a pattern is suggestive of extrasynaptic GABAA receptor labelling, it is also possible that most of the α1 subunit immunoreactivity reflects intracellular pools of subunit protein (or assembled receptors).

Normal maturation and subcellular localization of subunits forming extrasynaptic GABAA receptors

The increase in tonic inhibition measured electrophysiologically between P10 and P20 was mirrored by a developmentally regulated expression of the α4 subunit in the VB, as detected by immunoperoxidase staining (Fig. 10A–D) at these stages. No difference in the distribution, or staining intensity for the α4 subunit was evident between WT and α10/0 mice (compare Fig. 10A and B at P10 and Fig. 10C and D at P20). Similar findings were obtained for the δ subunit (not shown), which has a very similar distribution to that of the α4 subunit in VB. On the subcellular level, no colocalization between the α4 subunit and gephyrin was evident in sections from WT (not shown) and mutant mice (Fig. 10E), whereas in the same tissue, γ2 subunit immunofluorescence formed bright clusters colocalized with gephyrin (Fig. 10F). At P20, in line with the loss of postsynaptic GABAA receptors, the γ2 subunit was almost undetectable, whereas the α4 subunit immunoreactivity was diffuse in the neuropil (Fig. 10G and H), as reported previously for adult mice (Kralic et al. 2006). These results confirm the independent regulation of α subunit variants and support functional data that α4-GABAA receptors do not contribute to synaptic transmission in VB neurones.

Figure 10. Comparative distribution of the α4 subunit immunoreactivity in VB of WT and α10/0 mice at P10 and P20, as illustrated by immunoperoxidase staining.

A, B, A moderate staining for the α4 subunit selectively present in VB, but not in the nRT, is already evident at P10, with a similar distribution in both genotypes. C, D, The staining intensity increases until P20, without revealing differences between WT and α10/0 mice at this stage. E–H, double immunofluorescence for gephyrin (red) and the α4 (green; E and G) or γ2 (green; F and H) subunit at P10 and P20 in α10/0 mice; the extrasynaptic localization of the α4 subunit is inferred from its lack of colocalization with gephyrin, despite the absence of the α1 subunit at either stage. Note that the γ2 subunit staining intensity decreases dramatically between P10 and P20, reflecting the loss of mIPSCs recorded electrophysiologically. Scale bars: D (applies for A–D), 100 μm; H (applies for E–H), 2 μm.

Long-term preservation of GABA-ergic terminals in VB of α10/0 mice

The disappearance of phasic GABAA receptor-mediated transmission and the maintenance of tonic inhibition raised the question to what extent GABA-ergic terminals are affected in the VB of α10/0 mice. Immunofluorescence staining for VGAT revealed no difference between genotypes at every age examined. At high-magnification, double labelling for VGAT and gephyrin showed that almost all gephyrin clusters were apposed to GABA-ergic terminals, which frequently appeared to form multiple postsynaptic sites (Fig. 11A). In sections from α10/0 mice, gephyrin intracellular aggregates were not apposed to VGAT-positive terminals, whereas the clusters remaining in the absence of α1 subunit were still apparently postsynaptic, as shown for a section of a P30 mouse (Fig. 11B). A quantitative analysis confirmed these observations, showing no difference in the size of GABA-ergic terminals, as determined by cumulative distribution frequency analysis, or in their density, counted in three-dimensional volumes reconstructed from stacks of confocal images (Fig. 11C and D). The preservation of GABA-ergic terminals was also seen with immunofluorescence for GAT1 (not shown), and may account for the maintenance of tonic inhibition in the VB of mutant mice.

Figure 11. GABA-ergic terminals remain unaffected in the VB of α10/0 mice during development, as seen by double immunofluorescence staining (A, B) of vGAT (green) and gephyrin (red).

A, at P30, the close apposition of both markers confirms the postsynaptic localization of gephyrin clusters in both genotypes, whereas large aggregates are not associated with gephyrin. B, at P60, most gephyrin clusters have disappeared and are replaced by aggregates. C, the density of vGAT positive terminals formed at P10 remains constant until adulthood and does not differ between WT and α10/0 mice. D, likewise, their size, as determined by cumulative distribution analysis, is comparable in adult and WT α10/0 mice, despite the loss of postsynaptic proteins occurring in the mutants. Scale bar in B, 2 μm (applies to A and B).

Discussion

Four principal findings can be derived from this study. (1) During normal development, changes in GABAA receptor subunit repertoire and expression result in functional adaptations of both phasic and tonic inhibition; however, the functional properties of synaptic immature receptors, notably the decay time constants of mIPSCs, can adapt rapidly without changes in subunit composition. (2) Tonic inhibition increases during development, independently of phasic inhibition and is maintained in adult VB neurones that lack synaptic GABAA receptors. (3) The expression profile of each GABAA receptor subtype is independent of other subunits present in VB neurones, and no functional substitution occurs between subunits contributing to synaptic and extrasynaptic receptors. And (4) the maintenance of a gephyrin postsynaptic scaffold depends on the presence of synaptic GABAA receptors; however, presynaptic terminals are retained in the absence of functional synaptic transmission.

Development of synaptic GABAA receptors

P8–9 VB GABA-ergic synapses initially contain α2-GABAA receptors, clustered at presumptive postsynaptic sites with gephyrin. The reduced effect of a non-selective concentration of zolpidem on the decay of mIPSCs recorded from α2H101R neurones confirms that these relatively slow synaptic events are mediated by α2-GABAA receptors. Within the next 24–48 h the mIPSC decay time decreases considerably, allowing increased temporal precision, a common feature of neuronal maturation. Similar changes with development are documented for synaptic transmission mediated by ionotropic glutamate, nicotinic, glycine and GABAA receptors and changes to receptor subunit composition are often suspected (Takahashi, 2005). Inhibitory synapses of mature VB neurones express α1-GABAA receptors (Kralic et al. 2006) and the appearance of this subunit has been implicated in developmental changes to synaptic transmission (Okada et al. 2000; Goldstein et al. 2002; Ortinski et al. 2004; Bosman et al. 2005). However, P10 VB neurones exhibit little α1 subunit staining, with the majority of gephyrin clusters incorporating the α2 subunit. In agreement, a low concentration of zolpidem, an α1 subunit selective ligand, had little, or no effect on WT P10–11 mIPSCs, and this situation was not significantly different from that determined for neurones derived from α1H101R mice. Providing further support, the mIPSCs of P10 α10/0 VB neurones were indistinguishable from WT (by P10, both strains exhibited rapidly decaying mIPSCs). Therefore, unexpectedly, the perturbation of VB mIPSC kinetics was not caused by the expression of the α1 subunit, but reflects a rapid maturation of α2-GABAA receptor containing synapses.

Several alternative mechanism(s) underlying these kinetic changes are conceivable: receptors containing α4 and γ2 subunits exhibit relatively rapid kinetics (Lagrange et al. 2007; Picton & Fisher, 2007). However, the α4 subunit immunofluorescence did not colocalize with gephyrin clusters and the effects of Ro15-4513 did not support the presence of synaptic α4-GABAA receptors in either WT, or α10/0 P10–11 neurones. In developing spinal neurones a change in neurosteroid levels influences mIPSC kinetics (Keller et al. 2004). Thalamic nRT neurones express neurosteroid synthesizing enzymes (Agis-Balboa et al. 2006), but it is not known whether neurosteroids produced in the nRT would act on the VB. Alternatively, changes to the kinetics of neurotransmitter release, expression of GABA transporters, post-translational modifications of postsynaptic proteins, or alterations of the cytoskeleton could influence mIPSC kinetics (Jones & Westbrook, 1997; Petrini et al. 2003; Mozrzymas, 2004; Cathala et al. 2005; Takahashi, 2005; Chen & Olsen, 2007). Note we also found the mIPSC decay of nRT neurones to decrease with development. In contrast to VB neurones, the subunit composition of the nRT synaptic GABAA receptors (α3β3γ2) is stable throughout development (Studer et al. 2006). Hence, during thalamic development, the inhibitory synaptic responses of both GABA-ergic interneurones, and thalamocortical neurones undergo kinetic changes, which are not primarily caused by a change in the GABAA receptor isoform.

During the next 10 days of development in VB neurones, the gephyrin–α2 subunit clusters undergo considerable reorganization so that by P20, nearly all such assemblies now contain the α1 subunit. The differential effects of zolpidem and Ro15-4513 on mIPSCs recorded from WT and α1H101R VB neurones confirms the synaptic incorporation of α1-GABAA receptors in ≥ P15 VB neurones. Whether the subunit switch occurs within existing synapses, or whether synapses containing α2-GABAA receptors are replaced by novel ones incorporating the α1 subunit is not known. The maintenance of ‘orphan’ gephyrin clusters for several weeks in the VB neurones of α10/0 mice favours the former scenario. The developmental loss of gephyrin–α2 subunit clusters occurs irrespective of the α1 subunit. In agreement, although deletion of the α1 subunit had no effect on the synaptic responses of P8–11 VB neurones, with subsequent development the proportion of α10/0 neurones exhibiting mIPSCs decreased, until by P23–27 all neurones were ‘silent’. Evidently, these neurones (post P15) cannot stray from the developmental programme and default to re-synthesize the α2 subunit. Although increased staining of the α4 subunit is evident in the VB neurones of α10/0 mice, this subunit does not cluster with gephyrin and the absence of mIPSCs illustrates that this extrasynaptic subunit cannot deputize for the synaptic α1 subunit (Chandra et al. 2006; Kralic et al. 2006).

Mechanism of gephyrin clustering

Surprisingly, the gephyrin clusters of VB α10/0 mice remained for an extended time at presumptive postsynaptic sites devoid of functional GABAA receptors. In juvenile mice conditional knockout of the γ2 subunit in cerebral cortex and hippocampus caused gephyrin clusters to disappear within a few days (Schweizer et al. 2003). Although the γ2 subunit was not targeted in α10/0 mice, it also loses its’ postsynaptic localization, suggesting cell-specific differences in the stability of gephyrin clusters. Whether these differences reflect the molecular heterogeneity of gephyrin, or other components of GABA-ergic synapses is not established. In this regard, collybistin-null mice exhibit striking regional differences in the loss of postsynaptic gephyrin/GABAA receptor clusters in the absence of this GDP/GTP-exchange factor, known to interact with gephyrin (Papadopoulos et al. 2007).

Development of GABA-ergic terminals

Although the mean absolute number of GABA-ergic synapses per VB neurone could not be quantified morphologically (using VGAT staining), an increase in synaptic coverage per relay neurone is likely, given the increased frequency of mIPSCs during development and the similar density of gephyrin clusters seen in WT mice, despite the considerable growth of the neuropil in VB between birth and P30. Analysis of GABA-ergic terminals with VGAT revealed no detectable morphological alteration in VB neurones of α10/0 mice, contrasting with the changes observed in the cerebellum of α10/0 mice and in the nRT of α30/0 mice (Kralic et al. 2006; Studer et al. 2006). Since VGAT is the vesicular transporter for GABA (and glycine), the storage of GABA in presynaptic vesicles remains operant and probably sustains the tonic GABA-ergic inhibition in VB neurones. The long-term maintenance of postsynaptic sites is therefore not essential for GABA-ergic terminals. In the cerebellum, immunoelectron microscopy reveals that such ‘orphan’ terminals make aberrant synapses with the spines of Purkinje cells (Fritschy et al. 2006). Whether they find a novel postsynaptic partner in VB neurones is not known.

Development of extrasynaptic GABAA receptors

The tonic current increased considerably (∼4-fold) during postnatal weeks 3–4. Therefore, considering the total charge transfer in developing VB neurones the emphasis is switched from synaptic transmission, which is temporally and spatially restricted, to asynchronous activation of extrasynaptic receptors. Experiments with THIP and our immunohistochemical data suggest an increased α4δ-GABAA receptor expression primarily accounts for the increase in tonic inhibition.

Although a large proportion of the α1 subunit staining in WT mice is not associated with gephyrin, we found no evidence for a contribution of α1-GABAA receptors to tonic inhibition. Therefore, this immunohistochemical signal may represent intracellular α1 subunit protein. The predominant contribution of α4-GABAA receptors to tonic inhibition is also supported by the fact that deletion of this subunit selectively abolished the VB tonic conductance, with no effect on IPSCs (Chandra et al. 2006). Hence, the α1 subunit cannot deputize for the extrasynaptic α4 subunit, nor can α4 replace the synaptic α1 subunit. This specificity appears host specific as receptors composed of α1 and δ subunits are readily expressed in cell lines and hippocampal interneurones (Wohlfarth et al. 2002; Glykys et al. 2007).

In contrast to the target specificity of the α subunit, in ≥ P15 VB neurones the β2 subunit is expressed both synaptically and extrasynaptically (Belelli et al. 2005) and appears synchronously (∼P15) in these distinct receptor populations, suggesting a coordinated synthesis. Similarly, we find extrasynaptic receptors of dentate gyrus granule cells (DGGCs) to incorporate the β2 subunit (Herd et al. 2008). Therefore, α4β2δ receptors are expressed in two distinct neuronal populations.

In conclusion, during ontogeny, thalamic relay neurones undergo a considerable reorganization of inhibitory synapses, coincident with the establishment of extrasynaptic GABAA receptors. The time course of synaptic inhibition can influence neuronal signal integration and consequently network activity (Jefferys et al. 1996). Therefore, the developmental changes to the duration of synaptic inhibition may have an impact on thalamo-cortical oscillations. In rat (P14–21) VB neurones activation of extrasynaptic GABAA receptors causes a hyperpolarization that leads to a ‘burst firing’ mode (Cope et al. 2005). However, in many developing neurones GABA produces a depolarization, due to an immature Cl− gradient. Therefore it will be important to investigate the nature of the GABA response during the period associated with the development of the tonic conductance. Future studies on the impact of development to thalamic network activity should permit a better understanding of how synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAA receptors act in concert to accommodate the challenges of neuronal maturation.

Acknowledgments

This work was upported by a BBSRC project grant, Tenovus Tayside and the Anonymous Trust (J.J.L. and D.B.), the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant no. 3100A0-108260 to J.M.F.) and NIH (AA10422 to G.E.H.).

References

- Agis-Balboa RC, Pinna G, Zhubi A, Maloku E, Veldic M, Costa E, Guidotti A. Characterization of brain neurones that express enzymes mediating neurosteroid biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14602–14607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606544103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard EA, Skolnick P, Olsen RW, Mohler H, Sieghart W, Biggio G, Braestrup C, Bateson AN, Langer SZ. International Union of Pharmacology. XV. Subtypes of gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptors: classification on the basis of subunit structure and receptor function. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:291–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belelli D, Herd MB, Mitchell EA, Peden DR, Vardy AW, Gentet L, Lambert JJ. Neuroactive steroids and inhibitory neurotransmission: mechanisms of action and physiological relevance. Neuroscience. 2006;138:821–829. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belelli D, Peden DR, Rosahl TW, Wafford KA, Lambert JJ. Extrasynaptic GABAA receptors of thalamocortical neurones: a molecular target for hypnotics. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11513–11520. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2679-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson JA, Low K, Keist R, Mohler H, Rudolph U. Pharmacology of recombinant γ-aminobutyric acidA receptors rendered diazepam-insensitive by point-mutated α-subunits. FEBS Lett. 1998;431:400–404. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00803-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosman LW, Heinen K, Spijker S, Brussaard AB. Mice lacking the major adult GABAA receptor subtype have normal number of synapses, but retain juvenile IPSC kinetics until adulthood. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:338–346. doi: 10.1152/jn.00084.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bright DP, Aller MI, Brickley SG. Synaptic release generates a tonic GABAA receptor-mediated conductance that modulates burst precision in thalamic relay neurones. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2560–2569. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5100-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne SH, Kang J, Akk G, Chiang LW, Schulman H, Huguenard JR, Prince DA. Kinetic and pharmacological properties of GABAA receptors in single thalamic neurones and GABAA subunit expression. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:2312–2322. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.5.2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cathala L, Holderith NB, Nusser Z, DiGregorio DA, Cull-Candy SG. Changes in synaptic structure underlie the developmental speeding of AMPA receptor-mediated EPSCs. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1310–1318. doi: 10.1038/nn1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra D, Jia F, Liang J, Peng Z, Suryanarayanan A, Werner DF, Spigelman I, Houser CR, Olsen RW, Harrison NL, Homanics GE. GABAA receptor α4 subunits mediate extrasynaptic inhibition in thalamus and dentate gyrus and the action of gaboxadol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15230–15235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604304103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZW, Olsen RW. GABAA receptor associated proteins: a key factor regulating GABAA receptor function. J Neurochem. 2007;100:279–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti F, Minelli A, Melone M. GABA transporters in the mammalian cerebral cortex: localization, development and pathological implications. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2004;45:196–212. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope DW, Hughes SW, Crunelli V. GABAA receptor-mediated tonic inhibition in thalamic neurones. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11553–11563. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3362-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias R, Sheppard WF, Fradley RL, Garrett EM, Stanley JL, Tye SJ, Goodacre S, Lincoln RJ, Cook SM, Conley R, Hallett D, Humphries AC, Thompson SA, Wafford KA, Street LJ, Castro JL, Whiting PJ, Rosahl TW, Atack JR, McKernan RM, Dawson GR, Reynolds DS. Evidence for a significant role of α3-containing GABAA receptors in mediating the anxiolytic effects of benzodiazepines. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10682–10688. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1166-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrant M, Nusser Z. Variations on an inhibitory theme: phasic and tonic activation of GABAA receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:215–229. doi: 10.1038/nrn1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, Brünig I. Formation and plasticity of GABAergic synapses: physiological mechanisms and pathophysiological implications. Pharmacol Ther. 2003;98:299–323. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(03)00037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, Mohler H. GABAA-receptor heterogeneity in the adult rat brain: differential regional and cellular distribution of seven major subunits. J Comp Neurol. 1995;359:154–194. doi: 10.1002/cne.903590111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, Panzanelli P, Kralic JE, Vogt KE, Sassoè-Pognetto M. Differential dependence of axo-dendritic and axo-somatic GABAergic synapses on GABAA receptors containing the α1 subunit in Purkinje cells. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3245–3255. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5118-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, Paysan J, Enna A, Mohler H. Switch in the expression of rat GABAA-receptor subtypes during postnatal development: an immunohistochemical study. J Neurosci. 1994;14:5302–5324. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05302.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glykys J, Peng Z, Chandra D, Homanics GE, Houser CR, Mody I. A new naturally occurring GABAA receptor subunit partnership with high sensitivity to ethanol. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:40–48. doi: 10.1038/nn1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]