Abstract

The mouse is refractory to lithogenic agents active in rats and humans, and so has been traditionally considered a poor experimental model for nephrolithiasis. However, recent studies have identified slc26a6 as an oxalate nephrolithiasis gene in the mouse. Here we extend our earlier demonstration of different anion selectivities of the orthologous mouse and human SLC26A6 polypeptides to investigate the correlation between species-specific differences in SLC26A6 oxalate/anion exchange properties as expressed in Xenopus oocytes and in reported nephrolithiasis susceptibility. We find that human SLC26A6 mediates minimal rates of Cl− exchange for Cl−, sulphate or formate, but rates of oxalate/Cl− exchange roughly equivalent to those of mouse slc2a6. Both transporters exhibit highly cooperative dependence of oxalate efflux rate on extracellular [Cl−], but whereas the K1/2 for extracellular [Cl−] is only 8 mm for mouse slc26a6, that for human SLC26A6 is 62 mm. This latter value approximates the reported mean luminal [Cl−] of postprandial human jejunal chyme, and reflects contributions from both transmembrane and C-terminal cytoplasmic domains of human SLC26A6. Human SLC26A6 variant V185M exhibits altered [Cl−] dependence and reduced rates of oxalate/Cl− exchange. Whereas mouse slc26a6 mediates bidirectional electrogenic oxalate/Cl− exchange, human SLC26A6-mediated oxalate transport appears to be electroneutral. We hypothesize that the low extracellular Cl− affinity and apparent electroneutrality of oxalate efflux characterizing human SLC26A6 may partially explain the high human susceptibility to nephrolithiasis relative to that of mouse. SLC26A6 sequence variant(s) are candidate risk modifiers for nephrolithiasis.

5% of females and 10–20% of males in the US population will experience at least one kidney stone over the course of a lifetime. 80% of these kidney stones contain calcium, and most are predominantly calcium oxalate (Coe et al. 2005; Taylor & Curhan, 2007). Elevation of urinary oxalate excretion is a major risk factor for nephrolithiasis. As urinary oxalate represents the sum of dietary intake and endogenous production, control of dietary oxalate intake has been recommended as part of standard treatment. However, absorbed dietary oxalate has been estimated as the source of only 5–20% of excreted urinary oxalate (although values of up to 42% have also been reported) (Holmes et al. 2001). Indeed, recent studies have demonstrated minimal impact of dietary oxalate on the frequency of stone disease (Taylor & Curhan, 2007). Most urinary oxalate arises in the course of normal metabolism of the oxalate precursors glycine, glycolate, hydroxyproline, and ascorbate. Normal human serum free oxalate concentrations of ∼1.5 μm (Harris et al. 2004), can rise in the setting of end-stage renal disease to predialysis values of 35 μm and higher, and to 130 μm or more in the context of familial primary hyperoxalurias (Yamauchi et al. 2001). Eighty-nine to 99% of intravenously injected oxalate is cleared by the kidney (Osswald & Hautmann, 1979; Ribaya & Gershoff, 1982), but colonic oxalate secretion can be up-regulated in the presence of renal insufficiency, leading to increased fractional fecal excretion of oxalate (Hatch et al. 1999).

Strategies to prevent kidney stone formation or recurrence include attempts to decrease urinary oxalate excretion. Regulation of endogenous oxalate production is not yet possible. As the influence of dietary oxalate load on lithogenesis remains uncertain, interest has increased in possible therapeutic enhancement of the small fecal fraction of oxalate excretion. Strategies to increase oxalate degradation by luminal oxalate-metabolizing bacteria are in current clinical trial. The beneficial impact of such a strategy should in principle be strengthened by agents or manoeuvres that act on enterocytes to decrease intestinal enterocyte oxalate absorption and/or enhance intestinal oxalate secretion.

The oxalate uptake pathway of the enterocyte apical membrane remains unidentified, but the main apical oxalate secretion pathway was recently defined in the mouse. Genetic deletion of the oxalate/anion exchanger gene slc26a6 causes spontaneous calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis in the setting of hyperoxalaemia, hyperoxaluria, and nephrocalcinosis. The hyperoxaluria in this model can be attributed to loss of most duodenal oxalate secretion without change in oxalate absorption (Jiang et al. 2006). In a different slc26a6−/− mouse model, hyperoxaluria is attributable to loss of half of distal ileal oxalate secretion accompanied by doubling of oxalate absorption (Freel et al. 2006). These murine phenotypes are remarkable in view of the extreme refractoriness of wild-type mouse strains to dietary or pharmacological induction of nephrolithiasis (Wesson et al. 2003). Moreover, the phenotypes highlight the importance of intestinal oxalate secretion in serum oxalate homeostasis and in protection of the kidney from calcium oxalate precipitation in the setting of urinary supersaturation.

We hypothesized that the contrasting high human susceptibility and low wild-type murine susceptibility to oxalate nephrolithiasis might reflect in part the divergent anion transport properties of the orthologous SLC26A6 polypeptides. We showed previously that mouse slc26a6 and human SLC26A6, which share only 78% amino acid identity, exhibit substantial differences in anion selectivity attributable in part to divergent amino acid sequences of the transmembrane domains (Chernova et al. 2005). Here, we compare in greater detail the oxalate and chloride transport properties of human SLC26A6, mouse slc26a6, and their chimeric polypeptides. We show that human SLC26A6 mediates oxalate efflux from Xenopus oocytes with an affinity for extracellular Cl− much lower than that of mouse slc26a6. We also show that oxalate/Cl− exchange by human SLC26A6 is electroneutral, in contrast to the electrogenic oxalate/Cl− exchange mediated by the mouse orthologue. Each of these species-specific properties of SLC26A6 is predicted to enhance secretion of oxalate by mouse intestine, but to render suboptimal oxalate secretion by human intestine under resting conditions. We suggest that these characteristics of human SLC26A6-mediated oxalate secretion may explain, in part, the high human susceptibility to oxalate nephrolithiasis in contrast to the low susceptibility of the mouse.

Methods

Materials

Na36Cl, Na235SO42−, and Na[14C]formate were obtained from ICN (Irvine, CA, USA). [14C]Oxalate originally from NEN-DuPont was the generous gift of C. Scheid and T. Honeyman (University of Massachusetts Medical Center). Restriction enzymes and T4 DNA ligase were from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA, USA). The EXPAND High-fidelity PCR System was obtained from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN, USA). 4,4′-Diisothiocyanostilbene-2,2′-disulphonic acid (DIDS) was from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA, USA). All other chemical reagents were from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA) or Fluka (Milwaukee, WI, USA) and were of reagent grade.

Construction of chimeric and variant cDNAs

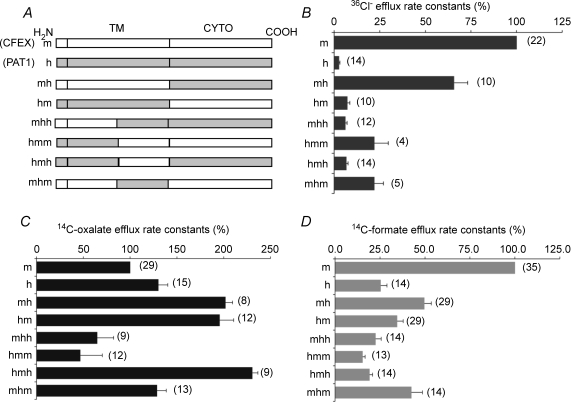

The cDNAs studied are presented in the schematic diagram of Fig. 1A. Mouse slc26a6 in pCMV-SPORT6 was obtained from the Mammalian Genome Collection (MGC_25824, IMAGE:4165725, BC028856 from the FVB/N strain). This clone encoding polymorphic amino acid residues E2 and R549 corresponds to the ‘S-Q’ variant of human, as the residue equivalent to human Q611 (short variants) or Q632 (long variants) is absent from the mouse gene. Human SLC26A6 S-Q was generated as described by PCR mutagenesis (Chernova et al. 2005) from the Human SLC26A6 L-Q variant in pCMV-SPORT6 (MGC_21068, IMAGE:4398446, BC017697). The chimeric polypeptides shown in Fig. 1A are encoded by chimeric cDNAs constructed by four-primer polymerase chain reaction. Chimera ‘mh’ joins mouse slc26a6 aa 493 to human SLC26A6 S-Q aa 495, close to the boundary between the transmembrane domain and the long cytoplasmic C-terminal tail. Chimera ‘hm’ joins human SLC26A6 S-Q aa 494 to mouse aa 494. Chimeras ‘mhh’ and ‘mhm’ join mouse aa 265 to human aa 267 roughly in the mid-transmembrane domain. Chimeras ‘hmh’ and ‘hmm’ join human aa 266 to mouse aa 266. Chimeras ‘mhm and ‘hmh’ also share the above-described transmembrane-cytoplasmic domain junction. Human SLC26A6 S-Q variant V185M (Fig. 5) was also constructed by four-primer polymerase chain reaction. Primer sequences are presented in online supplemental material, Supplemental Table 1.

Figure 1. Relative rates of tracer anion efflux by SLC26A6 chimeras, normalized to rate constants of wild-type mouse slc26a6.

A, schematic diagram of mouse slc26a6/human SLC26A6 chimeras tested. B, normalized 36Cl− efflux rate constants measured in Cl− bath (with 100% value assigned to mouse slc26a6). Human SLC26A6 mediated minimal Cl− efflux, whereas chimera mh exhibited nearly 70% of the activity displayed by mouse slc26a6 (P < 0.05). C, normalized [14C]oxalate efflux rate constants measured in Cl− bath differed minimally between human SLC26A6 and mouse slc26a6 (P < 0.05). Rate constants for other constructs equalled or exceeded that of mouse slc26a6, except for mhh and hmm (P < 0.03). D, normalized [14C]formate efflux rate constants measured in Cl− bath. Human SLC26A6-mediated formate efflux was only 25%, whereas chimera mh-mediated efflux was nearly 50% that of mouse slc26a6 (P < 0.05). The formate rate constant for construct mhh did not differ from that in DIDS (P = 0.4). Water-corrected values are means ±s.e.m. for (n) oocytes. Mouse slc26a6 efflux rate constants were 0.133 ± 0.017 for 36Cl−, 0.091 ± 0.07 for [14C]oxalate, and 0.026 ± 0.005 for [14C]formate. Efflux differences among constructs were significant by ANOVA for each substrate anion (P < 0.05). All oocytes were injected with 10 ng of the indicated cRNA. 36Cl− rate constants for m, h, mh and hm are reproduced from Chernova et al. (2005).

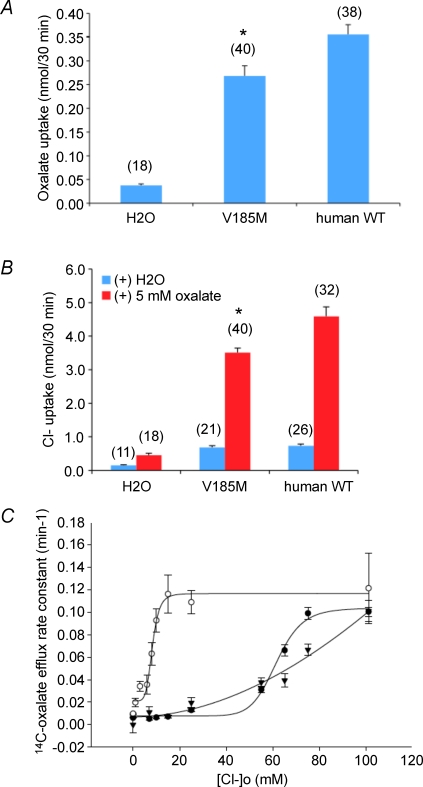

Figure 5. Functional effect of human SLC26A6 V185M polymorphism.

A, [14C]oxalate uptake by oocytes expressing human wild-type SLC26A6 or the variant V185M, or by oocytes previously injected with water. *P < 0.005 compared to wild-type. B, 36Cl− uptake by oocytes expressing human WT SLC26A6 or the variant V185M, or by oocytes previously injected with water, measured immediately after injection of 50 nl of water or oxalate. Values in panels A and B are means ±s.e.m. for (n) oocytes. *P < 0.002 compared to wild-type. C, bath [Cl−] dependence of [14C]oxalate efflux rate constant in oocytes expressing human SLC26A6 variant V185M (t, n = 18–30). Curve is a Hill fit to the data, which are compared with bath [Cl−] dependence of human WT SLC26A6 (•, n = 6–33) or mouse slc26a6 (○, n = 11–47) reproduced from Fig. 4C.

Solutions

ND-96 (pH 7.40) consisted of (mm): 96 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 Hepes and 2.5 sodium pyruvate, with100 mg ml−1 added gentamicin. ND-96 flux medium and other flux media lacked sodium pyruvate and gentamicin. In Cl−-free solutions, 96 mm NaCl was replaced with 96 mm sodium cyclamate. The Cl− salts of K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ were replaced on an equimolar basis by substituting the corresponding gluconate salts. Bath [Cl−] dependence was assessed by graded equimolar substitution of sodium cyclamate for NaCl. Addition to flux media of the weak acid salt sodium butyrate (40 mm) was in equimolar substitution for NaCl. When indicated, 24 mm NaHCO3 was substituted for 24 mm NaCl or sodium cyclamate in Hepes-free solutions of pH 7.40 and saturated with 5% CO2–95% air at room temperature for ∼1 h before use. The pH of CO2/HCO3−-buffered solutions was verified prior to each experiment.

Expression of cRNAs in Xenopus oocytes

Capped cRNA was transcribed from linearized cDNA templates with T7 RNA polymerase (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). RNA integrity was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis in formaldehyde. Mature female Xenopus (NASCO, Madison, WI, USA) were maintained and subjected to partial ovariectomy under hypothermic tricaine anaesthesia following protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Stage V–VI oocytes were manually defolliculated following incubation of ovarian fragments with 2 mg ml−1 collagenase A or collagenase B (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) for 60 min in ND-96. Oocytes were injected on the same or following day with cRNA (0.5–10 ng) or with water in a volume of 50 nl. Injected oocytes were then maintained for 2–6 days at 19°C before use. All human SLC26A6 constructs studied were based on the SLC26A6(S-Q) variant.

Isotopic anion flux assays

Unidirectional 36Cl− influx studies were carried out for periods of 30 min in ND-96 containing 10 μm bumetanide as previously described (Chernova et al. 2005). Total bath [Cl−] was 104 mm.[14C]Oxalate influx studies were carried out for 30 min periods in 96 mm sodium cyclamate influx medium lacking Ca2+ and Mg2+, and containing 1.0 mm sodium oxalate (5 μCi well−1; 150 μl). For unidirectional 36Cl− efflux studies individual oocytes in Cl−-free ND-96 were injected with 50 nl of 130 mm Na36Cl (10 000–12 000 c.p.m.). Following a 5–10 min recovery period in sodium cyclamate medium containing Ca2+ and Mg2+, the efflux assay was initiated by transfer of individual oocytes to 6 ml borosilicate glass tubes, each containing 1 ml efflux solution. At intervals of 1 or 2 min, 0.95 ml of this efflux solution was removed for scintillation counting and replaced with an equal volume of fresh efflux solution. Following completion of the assay with a final efflux period either in Cl−-free cyclamate solution or in the presence of the inhibitor DIDS (100 or 200 μm), each oocyte was lysed in 100 μl of 2% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS). Samples were counted for 3–5 min such that the magnitude of 2 s.d. was < 5% of the sample mean.

For [14C]oxalate efflux assays, oocytes were injected with 50 nl of 50 mm Na[14C]oxalate (6000–8000 c.p.m., with final estimated intracellular concentration 5 mm), and efflux was measured in baths containing 96 mm NaCl or sodium cyclamate. Chloride concentration–response curves were generated from individual oocytes subjected to overlapping subsets of five among the nine tested concentrations.

To vary pHi, oocytes were pre-exposed to 40 mm sodium butyrate (substituting for NaCl) for 30 min prior to initiation of an efflux experiment to produce intracellular acidification. Upon removal of butyrate from the bath (with restoration of chloride) during the course of the efflux experiment, pHi rapidly alkalinized while pHo remained constant. Variation of pHo was achieved at near-constant pHi (Stewart et al. 2002). Other oocyte groups were exposed to 20 mm NH4Cl during the course of efflux experiments. Drugs were added to the bath or were injected into oocytes either prior to or together with isotope as indicated.

Efflux data were plotted as ln (% c.p.m. remaining in the oocyte) versus time. 36Cl− and [14C]oxalate efflux rate constants were measured from linear fits to data from the last three time points sampled for each experimental condition/period. Within each experiment, water-injected and cRNA-injected oocytes from the same frog were subjected to parallel measurements. Each experimental condition was tested in oocytes from at least two frogs. A priori exclusion criteria to define instances of ‘non-specific’ or ‘leak’ flux were < 50% inhibition of efflux rate in the presence of DIDS or the absence of bath chloride, or loss of > 95% of injected [14C]oxalate or > 85% of injected 36Cl− isotope prior to completion of the efflux assay.

Statistical analyses were by Student's paired or unpaired two-tailed t-tests, or by ANOVA (Microsoft Excel). Concentration dependence data were fitted to a four-parameter Hill equation in SigmaPlot 8.0 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

Two-electrode voltage clamp and membrane potential measurements

Microelectrodes from borosilicate glass made with a Narashige puller were filled with 3 m KCl and had resistances of 2–3 MΩ. Oocytes previously injected with water or with 10 ng of the indicated cRNA were placed in a 1 ml chamber (model RC-11, Warner Instruments, Hamden CT, USA) on the stage of a dissecting microscope and impaled with microelectrodes under direct view. Steady-state currents achieved within 2–5 min following bath change or drug addition were measured with a Geneclamp 500 amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA) interfaced to an Dell computer with a Digidata 1322A digitizer (Axon Instruments). Standard recording bath solution was (mm) 93.5 NaCl, 2 KCl, 5 Hepes, 2.8 MgCl2, with pH 7.40, or occasionally ND-96. In anion substitution experiments NaCl was replaced with Na+ or NMDG+ salts of gluconate, sulfamate or cyclamate. Bath addition of 1–5 mm sodium oxalate was performed in the presence of nominally Ca2+-free gluconate or sulfamate solution. Some oocytes were injected with 50 nl of 50 mm oxalate to achieve an estimated final intracellular concentration of 5 mm.

Data acquisition and analysis utilized pCLAMP 8.0 software (Axon Instruments). The voltage pulse protocol generated with the Clampex subroutine consisted of 20 mV steps between −100 mV and +40 mV, with durations of 738 ms separated by 30 ms at the holding potential of −30 mV. Bath resistance was minimized by the use of agar bridges filled with 3 m KCl, and a virtual ground circuit clamped bath potential to zero during voltage clamp experiments. Unclamped oocyte membrane potential was also recorded with the Geneclamp 500 amplifier. A bath electrode allowed correction for the potentials arising from bath solution changes.

Statistical analyses were by ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's t test for multiple samples (Sigmaplot 8.0).

Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy

Two days after injection with cRNA or water, individual oocytes were fixed for 30 min at room temperature in 1 ml 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Fixed oocytes (n = 8–10 per group) were extensively rinsed with PBS supplemented with 0.002% sodium azide, epitope-unmasked with 1% SDS for 1–5 min, and blocked in PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin and 0.05% saponin (PBS-BSA) for 1 h at 4°C. Oocytes were then incubated 4–16 h at 4°C with affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibody specific for mouse Slc26A6 C-terminal peptide (SA59, 1 : 1000 dilution) or specific for human SLC26A6 C-terminal peptide (1 : 200) (Chernova et al. 2005), washed several times in PBS-BSA, then incubated for 1 h with Cy3-conjugated secondary donkey anti-rabbit Ig (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA, USA), and again thoroughly washed in PBS-BSA. Oocytes expressing either mouse Slc26a6, human SLC26A6, chimera hmm, or chimera mhh were aligned in uniform orientation along a Plexiglas groove and sequentially imaged through the 10× objective of a Zeiss LSM510 laser confocal microscope using the 543 nm laser line at 512 × 512 resolution at a uniform setting of 80% intensity, pinhole 132 (1.68 Airy units), detector gain 682, Amp gain 1, zero amp offset.

Polypeptide abundance at or near each oocyte surface was estimated by quantification (ImageJ v. 1.38, NIH) of specific fluorescence intensity (FI) at the circumference of one quadrant of an equatorial focal plane (online supplemental material, Supplemental Fig. 1A and B). Mean background-corrected FI at or near the surface of oocytes previously injected with water was subtracted from the background-corrected FI at or near the surface of cRNA-injected oocytes to yield a value for surface-associated specific FI for each oocyte. Surface expression of chimeric polypeptides was normalized to that of the wild-type polypeptide detectable with the same primary antibody. Chimeric and wild-type specific fluorescence intensities were compared with Student's unpaired two-tailed t test. P < 0.05 was interpreted as significant.

Results

Robust [14C]oxalate efflux into Cl− bath by human SLC26A6 is accompanied by minimal 36Cl− efflux and modest [14C]formate efflux

We showed previously that oocytes expressing human SLC26A6 mediate very low levels of Cl−/Cl− exchange in comparison to mouse slc26a6, and that the low Cl− transport phenotype resided largely within the transmembrane domain (TMD) (Chernova et al. 2005). To investigate the possible roles of specific subdomains within the TMD we generated chimeric cDNAs subdividing the TMD into two parts (Fig. 1A). Figure 1B shows that inclusion of human sequence as either the C-terminal (hmm) or the N-terminal half of the TMD (mhh) greatly impaired 36Cl− efflux. Moreover, the presence in the chimera of the human cytoplasmic domain in the context of either chimeric TMD (mhh, hmh) was associated with apparently lower rates of Cl− transport than in comparable constructs including the mouse cytoplasmic domain (mhm, hmm). Thus, portions of the entire TMD contribute to the Cl− transport phenotype.

Transport of formate by human SLC26A6 was also severely reduced compared to that by mouse slc26a6, with a similar rank order of normalized rate constants among the chimeric polypeptides (Fig. 1D). However, the magnitude of [14C]oxalate efflux by human SLC26A6 was equivalent to or exceeded that by mouse slc26a6 (Fig. 1C). Moreover, 4 of 6 tested mouse–human chimeric polypeptides exhibited oxalate efflux rates higher than those of wild-type mouse slc26a6, and on a normalized basis all matched or exceeded those previously reported for [14C]oxalate influx (Chernova et al. 2005). This pattern of normalized rate constants among the chimeras differed markedly from those for efflux of chloride, sulphate, or formate. The anion efflux measurements of Fig. 1 reinforce the conclusion that human SLC26A6 is more specific for oxalate transport than is the orthologous mouse polypeptide.

Two of the six tested chimeras, mhh and hmm, exhibited reduced [14C]oxalate efflux compared to that of wild-type mouse Slc26a6 (Fig. 1C). To assess the degree to which altered surface expression contributed to this reduction in oxalate transport activity, we compared apparent polypeptide surface expression of these chimeric polypeptides with wild-type polypeptides using confocal laser scanning immunofluorescence microscopy with previously validated antibodies (Chernova et al. 2005) specific for the C-terminal peptide sequence of either human SLC26A6 or mouse Slc26a6 (Supplemental Fig. 1). Surface expression (n = 8–10 for all groups) was estimated as described in Methods by measurement of fluorescence intensity (ImageJ v. 1.38). Nominal surface expression of chimera mhh was 40% that of wild-type human SLS26A6 (P < 0.001), and so sufficed to account for the moderate reduction in oxalate efflux by mhh. Nominal surface expression of chimera hmm was 54% that of wild-type mouse Slc26a6 (P < 0.003), and so similarly sufficed to account for the corresponding reduction in oxalate efflux by hmm.

Extracellular Cl− affinity of mouse slc26a6 during Cl−/Cl− and oxalate/Cl− exchange modes

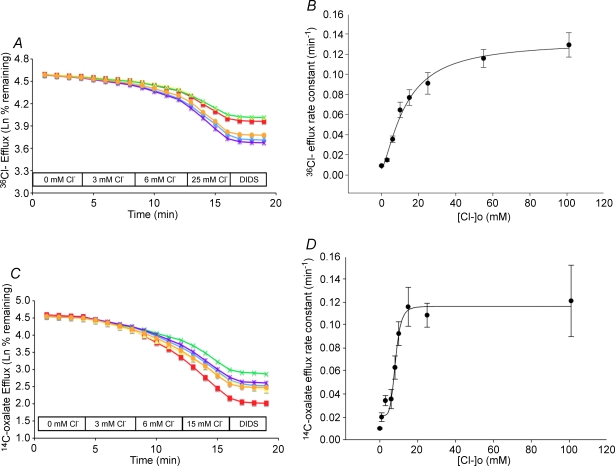

To investigate further the transport of oxalate and Cl−, we compared their extracellular interactions with those of mouse slc26a6. Figures 2A and B show that mouse slc26a6-mediated Cl−/Cl− exchange exhibits a K1/2 for extracellular Cl− of 13.1 ± 1.9 mm, with a Hill coefficient of 1.41 ± 0.27 (r2= 0.99). Mouse slc26a6-mediated oxalatei/ exchange (Fig. 2C and D) reveals a slightly lower K1/2 for extracellular Cl− of 8.3 ± 0.5 mm, with a higher Hill coefficient of 5.6 ± 1.8 (r2= 0.98). Thus, binding and translocation of extracellular Cl− to mouse slc26a6 are sensitive to the identity and/or charge of the intracellular trans-anion substrate.

Figure 2. concentration dependence of 36Cl− efflux and [14C]oxalate efflux by mouse slc26a6.

A, 36Cl− efflux traces from 6 individual oocytes expressing mouse slc26a6 and subjected in a single experiment to sequentially increasing bath [Cl−]. B, [Cl−]o dependence of mouse slc26a6-mediated Cl−/Cl− exchange measured as in panel A. Symbols represent mean rate constants ±s.e.m. for n = 11–30 oocytes. C, [14C]oxalate efflux traces from 6 individual oocytes expressing mouse slc26a6 and subjected in a single experiment to sequentially increasing bath [Cl−]. D, [Cl−]o dependence curve for mouse slc26a6-mediated oxalate/Cl− exchange measured as in panel C. Symbols represent mean rate constants ±s.e.m. for n = 11–47 oocytes. Curves in B and D are fitted by the 4-parameter Hill equation (SigmaPlot). Oocytes were injected with 10 ng mouse slc26a6 cRNA.

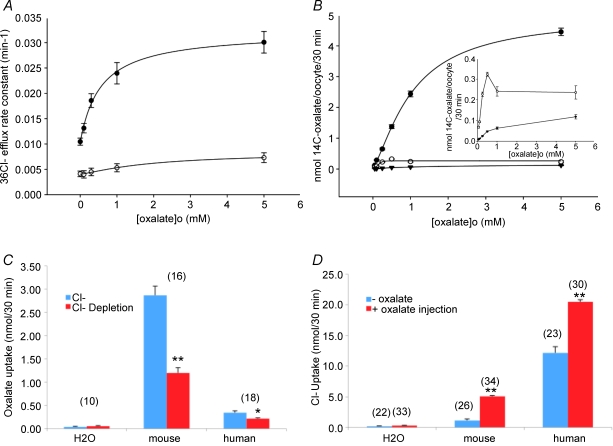

Extracellular oxalate affinity of mouse slc26a6 and human SLC26A6 during Cl−i/oxalateo exchange

Mouse slc26a6-mediated Cl−i/oxalateo exchange exhibited a K1/2 for extracellular oxalate of 0.56 ± 0.16 mm, with a Hill coefficient of 0.99 ± 0.22 (r2= 0.99) (Fig. 3A). Figure 3B shows that the K1/2 for extracellular oxalate measured as [14C]oxalate uptake (nominally Cl−/oxalate exchange) was 1.01 ± 0.04 mm, with a Hill coefficient of 1.41 ± 0.07 (r2= 0.99). 36Cl− efflux from oocytes expressing human SLC26A6 was too slow to evaluate for extracellular oxalate dependence (Fig. 3A). Human SLC26A6-mediated [14C]oxalate uptake (Fig. 3B) was lower than that by mouse slc26a6 but of higher oxalate sensitivity, with a K1/2 for extracellular oxalate of only 0.15 ± 0.06 mm (r2= 0.99). [14C]Oxalate uptake was diminished by prior overnight Cl− depletion of oocytes expressing either mouse slc26a6 or human SLC26A6 (Fig. 3C). Conversely, 36Cl− uptake into oocytes expressing either mouse or human protein was stimulated by acute oxalate loading of oocytes. This stimulation was proportionately more dramatic for human SLC26A6 (4.5-fold), though of lower magnitude, than for the substantially more active mouse slc26a6-mediated 36Cl− uptake (1.8-fold). Thus, both mouse and human orthologues mediate bidirectional oxalate/Cl− exchange. But human SLC26A6 exchanges intracellular oxalate for extracellular Cl− (Fig. 3D) much more readily than it exchanges intracellular Cl− for extracellular oxalate (Fig. 3A). Oxalate uptake by human SLC26A6 may be in exchange for another non-chloride anion.

Figure 3. Oxalateo concentration dependence of mouse slc26a6 and human SLC26A6 activities.

A, bath [oxalate] dependence of 36Cl− efflux rate constant in oocytes expressing mouse slc26a6 (•, n = 18) or human SLC26A6 (○, n = 18). B, bath [oxalate] dependence of [14C]oxalate uptake by oocytes expressing mouse slc26a6 (•, n = 25–50), human SLC26A6 (○, n = 25–54), or by oocytes previously injected with water (t, n = 16–44). Inset: y-axis magnification of uptake data for human SLC26A6 and water. Curves in panels A and B are fitted by the 4-parameter Hill equation. C, effect of overnight Cl− depletion on oxalate uptake by oocytes expressing mouse slc26a6 or human SLC26A6, or by oocytes previously injected with water. D, effect of acute oxalate injection on Cl− uptake by oocytes expressing mouse slc26a6 or human SLC26A6, or by oocytes previously injected with water. Values in panels C and D are means ±s.e.m. for (n) oocytes. (*P < 0.01; **P < 10−6).

Extracellular Cl− affinity of human SLC26A6 is much lower than that of mouse slc26a6

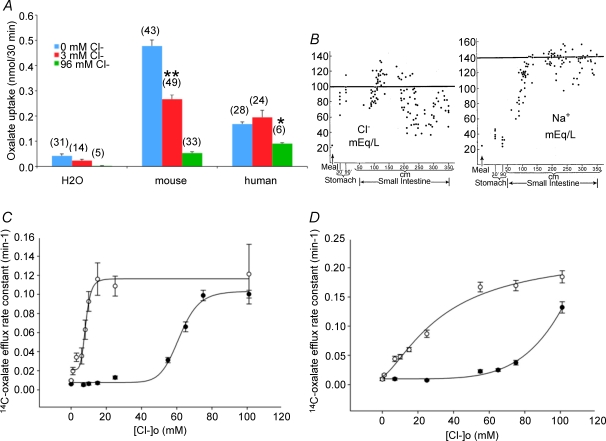

The low rates of 36Cl− uptake by human SLC26A6 (Figs 1 and 3) prompted determination of its extracellular Cl− affinity. In Fig. 4A, Cl− affinity was first estimated by the ability of extracellular Cl− to reduce uptake of [14C]oxalate. Extracellular Cl− of 3 mm reduced mouse slc26a6-mediated [14C]oxalate uptake by almost 40%, and 96 mm Cl− blocked it completely, consistent with the extracellular [Cl−] dependence of [14C]oxalate efflux (Fig. 2D). In contrast, 3 mm extracellular Cl− was without effect on human SLC26A6-mediated [14C]oxalate uptake, but 96 mm Cl− substantially reduced oxalate uptake.

Figure 4. Mouse slc26a6 and human SLC26A6 exhibit distinct affinities for extracellular Cl−.

A, effect of increasing bath [Cl−] from 0 to 3 to 96 mm on [14C]oxalate uptake by oocytes expressing mouse slc26a6, human SLC26A6, or by oocytes previously injected with water. Values in panels are means ±s.e.m. for (n) oocytes. **P < 10−6 compared to 0 mm[Cl−]; *P < 0.005 compared to 3 mm[Cl−]. B, postprandial luminal [Cl−] (left) and [Na+] in the human stomach, duodenum, and upper jejunumn (reproduced with permission from Fordtran & Locklear, 1966). C, bath [Cl−] dependence of [14C]oxalate efflux rate constant in oocytes expressing human SLC26A6 (•, n = 6–33) compared with oocytes expressing mouse slc26a6 (○, n = 11–47, reproduced from Fig. 2D). D, bath [Cl−] dependence of [14C]oxalate efflux rate constant in oocytes expressing chimeric SLC26A6 polypeptides ‘mh’ (○, n = 6–23) or ‘hm’ (•, 6–18) as schematized in Fig. 1A. Curves are Hill fits to the data.

This low apparent affinity of human SLC26A6 for extracellular Cl− is likely to have physiological importance, as shown in Fig. 4B. Fordtran & Locklear (1966) reported that [Cl−] of postprandial chyme fell to minimal values of between 30 and 80 mm after passage through the duodenum into the small intestine, while chyme [Na+] was maintained at or near 140 mm. (This observation led to the discovery of the role of apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange in NaCl absorption by intestinal mucosa; Turnberg et al. 1970a,b.) Indeed, more detailed measurement of the extracellular Cl− affinity for human SLC26A6-mediated [14C]oxalate efflux (Fig. 4C) revealed a K1/2 of 61.6 ± 1.4 mm with a Hill coefficient of 11 ± 2 (r2= 0.99).

To assess the relative contributions of TMD and cytoplasmic domain to this difference in extracellular Cl− affinity, mh and hm chimeras were similarly examined (Fig. 4D). [14C]Oxalate efflux by chimera mh exhibited an intermediate value of K1/2 for extracellular Cl− of 34.7 ± 11.3 mm (r2= 0.99), but with a Hill coefficient of 1.4 ± 0.35 resembling wild-type mouse slc26a6. The hm chimera showed even lower affinity for extracellular Cl− than wild-type human SLC26A6, with apparent retention of the steep Cl− concentration dependence exhibited by the human protein (failure to reach Cl− saturation prevented calculation of K1/2). Thus, the structural basis for the distinct extracellular Cl− affinities and the divergent values of the Hill coefficient of mouse and human SLC26A6 polypeptides resides primarily but not entirely in the TMD.

The intestine secretes oxalate in a CO2-buffered environment, and the presence of CO2/HCO3− may reduce the apparent extracellular Cl− affinity of human SLC26A3/DRA (Chernova et al. 2003; Lamprecht et al. 2005). Both SLC26A6 orthologues mediate oxalate/HCO3− exchange (Chernova et al. 2005; and data not shown), but addition of 24 mm HCO3−/5% CO2 to bath containing 60 or 72 mm Cl− failed to inhibit [14C]oxalate efflux rate constants for either human SLC26A6 (n = 23) or mouse slc26a6 (n = 12, P > 0.05, not shown).

A common human SLC26A6 variant exhibits altered [Cl−] dependence with slightly reduced oxalate/Cl− exchange rates at physiological gut lumen [Cl−]

The above data suggest that human SLC26A6-mediated oxalate efflux by jejunal enterocytes may be only half-maximally saturated by lumenal Cl−. In contrast, if the axial profile of mouse chyme [Cl−] resembles that measured in the human gut, intestinal oxalate secretion by mouse slc26a6 is likely always saturated with respect to extracellular Cl−. As sequence variation in human SLC26A6 may determine physiologically relevant differences in Cl− affinity and/or oxalate secretion rates, we evaluated transport properties of the common human SLC26A6 TMD variant V185M (NCBI SNP cluster report rs13324142). As shown in Fig. 5A, the human SLC26A6 variant V185M mediated slightly lower rates of [14C]oxalate uptake than wild-type SLC26A6. The low rates of 36Cl− uptake by oocytes expressing either polypeptide were greatly increased by acute oxalate injection: 5.7-fold for the V185M variant, but a greater 7.2-fold for wild-type SLC26A6 (Fig. 5B). In addition, rates of [14C]oxalate efflux by the V185M variant were significantly less than wild-type values at extracellular [Cl−] between 60 and 80 mm, consistent with a higher apparent K1/2 value for extracellular Cl− (Fig. 5C).

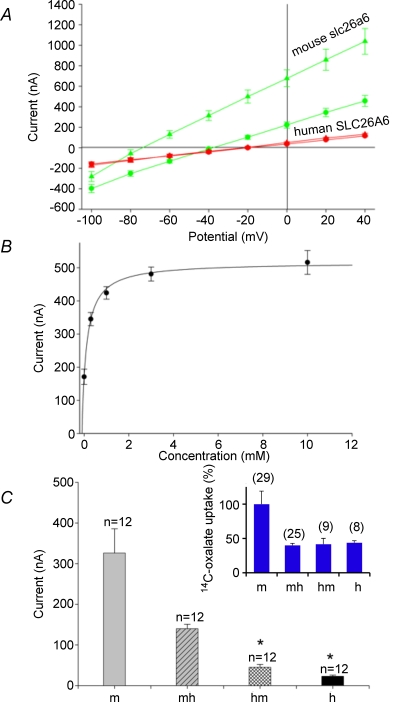

Exchange of extracellular oxalate for intracellular anion by human SLC26A6 is not detectably electrogenic, in contrast to that by mouse slc26a6

Oocytes expressing human SLC26A6 or mouse slc26a6 were subjected to voltage-clamp measurements of currents during sequential bath exposure to nominally Ca2+-free solutions of NaCl, Cl−-free sodium gluconate, and sodium gluconate containing 5 mm oxalate (Fig. 6A). Currents measured in human SLC26A6-expressing oocytes were indistinguishable from those in oocytes previously injected with water, and did not change upon Cl− removal or subsequent oxalate addition. Similar results were observed upon exposure to 10 mm (n = 5) or 1 mm oxalate (n = 7, not shown). Oocytes expressing mouse slc26a6 exhibited small linear currents which, upon Cl− removal, exhibited a minimal −3 mV shift (not shown) in reversal potential (Erev). However, subsequent addition of bath oxalate increased current magnitude and shifted Erev by −36 mV. Similar results were observed upon exposure to 1 mm bath oxalate (n = 8, not shown). This electrogenic exchange of extracellular oxalate for intracellular anion mediated by mouse slc26a6 corroborates in magnitude previously reported bath oxalate-dependent changes in oocyte current (Jiang et al. 2002). The results show that, in contrast to electrogenic exchange of intracellular Cl− for extracellular oxalate mediated by mouse slc26a6, human SLC26A6-mediated oxalate transport appears electroneutral.

Figure 6. Exchange of bath oxalate for intracellular anion is electrogenic when mediated by mouse slc26a6, but electroneutral when mediated by human SLC26A6.

A, I–V relationship measured in oocytes expressing mouse slc26a6 (open symbols, n = 47) or human SLC26A6 (filled symbols, n = 9) exposed first to NaCl bath, then to sodium gluconate (circles), and subsequently gluconate with 5 mm oxalate (triangles). Lines are least squares linear fits to the data. Data recorded in Cl− bath (not shown for clarity) was superposable with that in gluconate bath (circles). B, bath oxalate concentration dependence of current measured at +40 mV holding potential in 5 oocytes expressing mouse slc26a6. Data are fitted with the Hill equation. C, bath oxalate difference current measured at +40 mV in 12 oocytes (means ±s.e.m.) expressing mouse slc26a6 (m), human SLC26A6 (h) or the chimeric polypeptides mh or hm. *P < 0.05 compared to CFEX. Inset: normalized [14C]oxalate uptake measured on the same days in oocytes from the same two frogs (means ±s.e.m. for (n) oocytes).

At +40 mV holding potential, the outward current accompanying exchange of intracellular anion for extracellular oxalate by mouse slc26a6 exhibited a K1/2 for extracellular oxalate of 342 ± 42 μm (Fig. 6B, n = 5), in close agreement with the previously reported K1/2 value for [14C]oxalate influx of 314 μm (Jiang et al. 2002). The absence of bath oxalate-induced current in oocytes expressing human SLC26A6 prompted testing of mouse–human chimeras (Fig. 6C). In the same groups of oocytes in which human SLC26A6 and chimeric polypeptides exhibited [14C]oxalate influx at rates nearly 50% of that exhibited by mouse slc26a6 (inset), neither human SLC26A6 nor the hm chimera exhibited bath oxalate-induced current at +40 mV. However, chimera mh exhibited outward current in proportion to relative [14C]oxalate flux (inset), and this mh-mediated current was remarkable for a −37 mV shift in Erev upon bath addition of oxalate (not shown). Oocytes expressing chimeras hmm (and mhh (n = 19 each) exhibited currents at +40 mV not significantly different from those of water-injected oocytes (not shown). Thus electrogenic exchange of intracellular Cl− with extracellular oxalate requires the intact TMD of mouse scl26a6, and may also be enhanced by presence of the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain of the mouse protein.

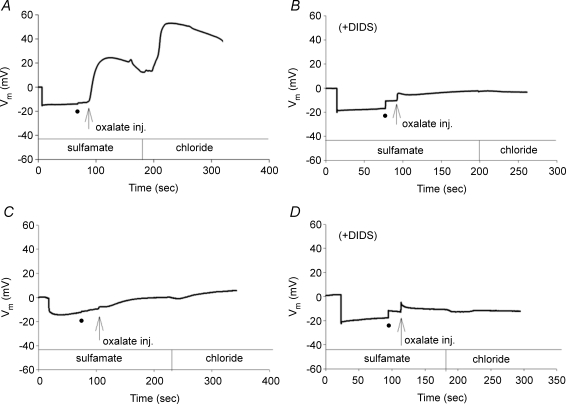

Exchange of intracellular oxalate for extracellular Cl− depolarizes oocytes expressing mouse slc26a6, but not human SLC26A6

Unclamped Vm in oocytes expressing mouse slc26a6 in Cl−-free sulfamate bath was −17.3 ± 0.8 mV, and responded to injection of oxalate (5 mm final estimated intracellular concentration) with depolarization of 45.5 ± 5.0 mV (n = 8). Subsequent bath change to Cl− further depolarized oocytes by an additional 30.8 ± 4.5 mV (n = 8) (Fig. 7A). Oocyte Vm was little changed at −14.2 ± 2.2 (n = 5) in the presence of 100 μm DIDS (Fig. 7B). Oxalate injection into these oocytes in the presence of DIDS only transiently depolarized oocytes by 9.2 ± 0.4 mV, followed by rapid return to the prior Vm. Further depolarization by restoration of extracellular Cl− was completely blocked by DIDS (Fig. 7B). Unclamped Vm of oocytes expressing human SLC26A6 was −12 ± 1.0 mV (n = 7), but oxalate injection only gradually depolarized these oocytes by 8.6 ± 1.0 mV, with no further depolarization upon restoration of bath Cl− (Fig. 7C; P < 0.001 for both transitions compared to mouse slc26a6). The presence of DIDS prevented even the small depolarization attendant to oxalate injection (Fig. 7D; n = 5). The DIDS-sensitive depolarization of oxalate-injected oocytes expressing mouse slc26a6 induced by extracellular Cl− suggested electrogenicity of oxalatei/Clo exchange that was not detected in oocytes expressing functional human SLC26A6. The large, initial DIDS-sensitive depolarization in the absence of extracellular Cl− observed only in mouse slc26a6-expressing oocytes was unexpected, but was minimal in oocytes expressing human SLC26A6.

Figure 7. Exchange of bath Cl− for intracellular oxalate depolarizes oocytes expressing mouse slc26a6 but not oocytes expressing human SLC26A6.

Vm recorded from representative individual oocytes expressing mouse slc26a6 (A, B) or human SLC26A6 (C, D) in the absence (A, C) or presence of 100 μM DIDS (B, D). In each panel the initial hyperpolarization reflects insertion of the recording pipette. Insertion of the injection pipette (black circle) is followed by oxalate injection (arrow) while the oocyte remains in sulfamate bath. The sulfamate bath is then replaced with Cl− bath.

Exchange of intracellular oxalate for extracellular Cl− by mouse slc26a6 is electrogenic, but that mediated by human SLC26A6 appears electroneutral

The Vm data of Fig. 7 suggested that the orthologous mouse and human SLC26A6 proteins differed in electrogenicity of bidirectional oxalate/Cl− exchange. Since oxalate efflux represents more closely the oxalate secretion of intestinal enterocytes absent in slc26a6−/− mice (Freel et al. 2006; Jiang et al. 2006), electrogenicity of exchange of intracellular oxalate for extracellular Cl− was tested further by two-electrode voltage clamp in a Na+-free bath (Fig. 8). Even in an NMDG-sulfamate bath, injection of oxalate into oocytes expressing mouse slc26a6 (Fig. 8A) substantially increased inward current measured at −100 mV from −337 ± 59 nA to −1162 ± 23 nA and shifted Erev+46.3 mV (n = 5). Subsequent bath change to NDMG-Cl further increased inward current measured at −100 mV to −1523 ± 108 nA (P < 0.001 compared to sulfamate), and further shifted Erev an additional +21.3 mV. Addition of DIDS completely inhibited both bath Cl−-dependent and -independent components of current induced by oxalate injection. Similar results were recorded in Na+-containing bath (n = 6, not shown). The bath Cl−-dependent component of current in oxalate-injected oocytes expressing mouse slc26a6 was attributable to electrogenic exchange of intracellular oxalate for extracellular Cl−. These data also suggest that oxalate injection induced a bath Cl−-independent inward current dependent on expression of mouse slc26a6.

Figure 8. Exchange of bath Cl− for intracellular oxalate by mouse slc26a6 (A) is electrogenic, but exchange by human SLC26A6 (B) is electroneutral.

Oocyte I–V curves were measured in NMDG sulfamate bath before (○) or after (•) injection of oxalate, then after bath change to NMDG chloride (▵) and finally, after addition of 100 μm DIDS (▴). Values are means ±s.e.m. for n = 5 oocytes in each panel. Lines are least squares linear fits to the data.

In contrast, as shown in Fig. 8B, oocytes expressing human SLC26A6 in NMDG sulfamate bath showed no increase in inward current upon oxalate injection, with only +5 mV shift in Erev (n = 5). Bath transition to NMDG-Cl minimally increased inward current and shifted Erev+8 mV, but subsequently addition of DIDS not only failed to reverse either the positive shifted Erev or the minimally increased inward current, but slightly increased both. Similar results were recorded in a Na+-containing bath (n = 4, not shown). Oocytes from the same frogs expressed robust [14C]oxalate efflux dependent on extracellular Cl− (not shown). Thus, human SLC26A6-mediated oxalatei/ exchange exhibited no evidence of electrogenicity. Moreover, oocytes expressing human SLC26A6 did not, upon oxalate injection, exhibit DIDS-sensitive bath Cl−-independent inward current observed in oocytes expressing mouse slc26a6.

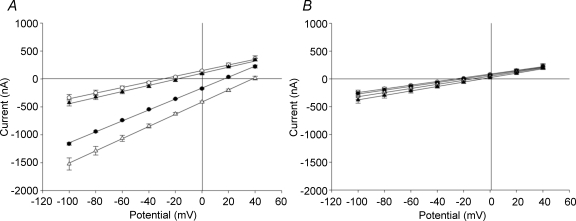

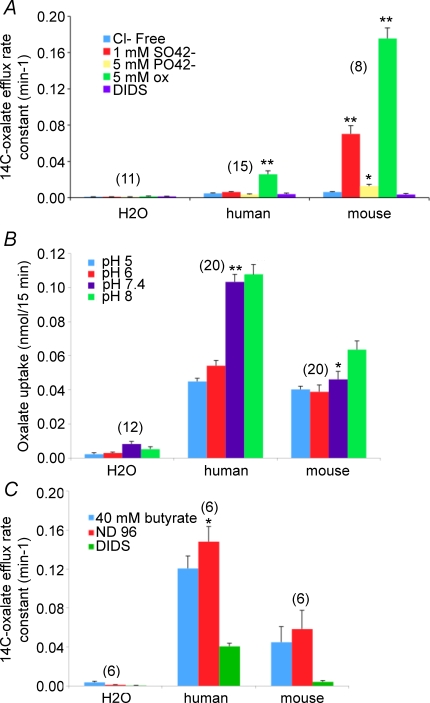

Divalent anion selectivity and pH sensitivity of human SLC26A6-mediated oxalate/Cl− exchange

Electroneutral oxalate/Cl− exchange by human SLC26A6 might be explained by preference for oxalate exchange with other divalent anions. As shown in Fig. 9A, both human and mouse proteins mediate DIDS-sensitive oxalate self-exchange. However, the robust oxalate/sulphate exchange and the lower rate of oxalate/phosphate exchange exhibited by mouse slc26a6 are absent from human SLC26A6. Neither protein mediates detectable oxalate exchange with citrate (not shown).

Figure 9. Tests of explanations for electroneutrality of human SLC26A6-mediated oxalate/Cl− exchange.

A, [14C]oxalate efflux rate constants for oocytes expressing human SLC26A6 or mouse slc26a6 and exposed sequentially to Cl−-free cyclamate bath without or containing sulphate, phosphate or oxalate, with a final addition of 100 μm DIDS. *P < 0.005; *P < 10−6 compared to cyclamate. B, extracellular pH dependence of oxalate uptake into oocytes expressing human SLC26A6 or mouse slc26a6. *P < 0.05 compared to pH 7.4; **P < 10−6 compared to pH 6. C, intracellular pH dependence of [14C]oxalate efflux rate constants in oocytes expressing human SLC26A6 or mouse slc26a6, measured as the response to bath butyrate removal. *P < 0.05 compared to presence of butyrate. Values are means ±s.e.m. for (n) oocytes.

Electroneutral oxalate/Cl− exchange by human SLC26A6 might also be explained by species-specific H+/oxalate cotransport, as has been measured for SLC4A1/AE1/Band 3 in the intact erythrocyte (Jennings & Adame, 1996) and in oocytes (A. K. Stewart and S. L. Alper, unpublished observations). However, oxalate uptake by human SLC26A6-expressing oocytes is inhibited by acidic extracellular pH, in contrast to the small effect of pHo on mouse slc26a6 (Fig. 9B; see also Jiang et al. 2002). Moreover, intracellular alkalinization by removal of preincubated sodium butyrate failed to inhibit [14C]oxalate efflux mediated by either human SLC26A6 or mouse slc26a6 (Fig. 9C). These data do not support H+/oxalate cotransport as a mechanism of oxalate influx or efflux by human or mouse SLC26A6. Thus, the structural and mechanistic bases for the differences in electrogenicity between the mouse and human SLC26A6 proteins remain unclear.

Discussion

SLC26A6 mediates oxalate secretion into the murine intestinal lumen in exchange for luminal anion, likely Cl− and/or HCO3−. Genetic inactivation of the mouse slc26a6 gene leads to hyperoxaluria and to nephrolithiasis in a species normally extremely refractory to pharmacological or dietary induction of kidney stones (Freel et al. 2006; Jiang et al. 2006). The much higher susceptibility of humans to kidney stone disease led us to test whether the substantial amino acid sequence differences between human SLC26A6 and mouse slc26a6 polypeptides encoded distinct anion transport properties that might in part explain the different susceptibilities of these two species to nephrolithiasis.

We found that human SLC26A6 has higher affinity for extracellular oxalate and much lower affinity for extracellular Cl− than does mouse slc26a6. The K1/2 values for extracellular Cl− suggest that whereas mouse slc26a6 is saturated by luminal [Cl−], human SLC26A6 is likely to be only half-maximally saturated. A common genetic variant of SLC26A6 mediated reduced rates of oxalate efflux at extracellular [Cl−] relevant to human intestinal oxalate secretion. Whereas oxalatei/ exchange by mouse slc26a6 is electrogenic, that by human SLC26A6 appears electroneutral. Thus, intestinal oxalate secretion by human SLC26A6 is likely to be rate-limited by subsaturating luminal [Cl−] in most individuals, whereas oxalate secretion by mouse slc26a6 is likely to operate at Vmax with respect to luminal [Cl−]. Moreover, oxalate secretion by human SLC26A6 appears insensitive to the favourable inside-negative electrical potential gradient that contributes to the driving force for oxalate secretion by mouse slc26a6. Both the low Cl− affinity and the absence of electrogenicity of human SLC26A6-mediated oxalate/Cl− exchange are encoded predominantly but not exclusively within the TMD.

Intestinal oxalate handling as a therapeutic target for treatment of hyperoxaluria

Hyperoxaluria is a major risk factor for nephrolithiasis, but dietary oxalate constitutes only a small fraction of total excreted oxalate. Most endogenous oxalate synthesis is believed to be hepatic in origin, although some arises (at least in the rat) from intestinal enterocytes (Ribaya & Gershoff, 1982). The great majority of the body's oxalate load is excreted in the urine, with only a small fraction excreted in faeces.

Treatment targets to achieve reduction of hyperoxaluria include inhibition of endogenous oxalate synthesis, inhibition of intestinal oxalate absorption, activation of intestinal oxalate secretion, and promotion of luminal oxalate degradation. Methods to inhibit endogenous oxalate biosynthesis are not available for individuals without the enzymatic deficiencies associated with hereditary hyperoxaluria syndromes. Inhibition of intestinal oxalate absorption is not straightforward since the molecular identity of the mediator(s) of this DIDS-insensitive, Na+-independent mucosal uptake process remains unknown. The discovery of slc26a6 as a major oxalate secretory pathway of mouse intestine suggests activation of intestinal oxalate secretion as an important and tractable therapeutic target in the treatment of hyperoxaluria. In order to prevent recycling of the incrementally secreted oxalate, such activator molecules would be most efficiently administered in concert with gut colonization by oxalate-degrading bacteria (Hoppe et al. 2006), which themselves may also directly stimulate colonic oxalate secretion (Hatch et al. 2006).

Cl− concentration-dependence of SLC26A6 orthologues

Although mouse slc26a6 has perhaps the widest anion selectivity yet reported among SLC26 polypeptides (Jiang et al. 2002; Xie et al. 2002), human SLC26A6 mediates only oxalate/Cl− exchange, among the exchange modalities tested in this work, at rates comparable to or exceeding mouse slc26a6. This oxalate/Cl− exchange exhibits a strong preference for oxalate secretion. Although both orthologous polypeptides exhibit a hyperbolic concentration dependence on extracellular oxalate (Fig. 3), they both exhibit a sigmoidal concentration dependence for extracellular Cl− (Fig. 4). This may reflect Cl−-induced conformational changes reflecting multiple anion binding sites per monomer or regulation of polypeptide oligomeric state (Zheng et al. 2006; Mio et al. 2008). Although kinetic studies of SLC4A1 suggest an alternating sites ‘ping-pong’ anion exchange mechanism (Restrepo et al. 1992), studies of SLC26 transport (Chernova et al. 2005; Shcheynikov et al. 2006) have not attempted discrimination between alternating and simultaneous mechanisms. Studies with chimeras suggest that the low affinity for extracellular Cl− of human SLC26A6 resides largely, but not exclusively, in the TMD. Studies with TMD chimeras show that both halves of the TMD contribute to the TMD component of the Cl− transport phenotype (Fig. 1).

Although human SLC26A6 also mediates oxalate self-exchange and oxalatei/HCO3−o exchange, rates of these exchange modes are modest compared to oxalatei/ exchange. Nonetheless, the high extracellular oxalate affinity of the human protein suggests the possibility that oxalate could more successfully compete with extracellular Cl− at the intestinal luminal surface, resulting in decreased oxalatei/ exchange and possibly increased (non-productive) oxalate self-exchange, or even net oxalate uptake in exchange for non-Cl− intracellular anion(s). The lower extracellular oxalate affinity and the electrogenicity of mouse slc26a6 together would disfavour oxalate uptake.

Electrogenicity of oxalate/Cl− exchange by mouse slc26a6

Bidirectional exchange of divalent oxalate for monovalent Cl− by mouse slc26a6 was clearly electrogenic (Figs 6–8). In contrast, oxalatei/ exchange by human SLC26A6 neither depolarized oocytes nor was accompanied by detectable voltage-clamp current. Since human SLC26A6-expressing oocytes from the same frogs exhibited bidirectional [14C]oxalate fluxes at rates comparable to those of mouse slc26a6, the lack of exchange-associated current was not attributable to expression levels below the level of detection. However, pH-dependent oxalate transport consistent with H+/oxalate cotransport was not present (Fig. 9). Meaningful rates of oxalate exchange with phosphate or sulphate were not detected.

Inward transport of two Cl− per outwardly transported oxalate anion remains possible for human SLC26A6, but precise transport stoichiometry remains to be established for the apparently electroneutral process, as intracellular free oxalate concentrations are unknown both before and after oocyte oxalate injection. Electrogenic oxalate/Cl− exchange mediated by slc26a5/prestin from chicken and from zebrafish was recently measured to be 1 : 1 (Schaechinger & Oliver, 2007), but prestin from higher vertebrates has yet to be convincingly associated with exchange current. Thus, mouse slc26a6 could either lack one extracellular Cl− binding site of the two possibly present in human SLC26A6, or have two Cl− binding sites, one of which is a transport site and one an allosteric regulatory site as postulated for mammalian prestin (Schaechinger & Oliver, 2007).

Oocytes expressing mouse slc26a6, but not human SLC26A6, exhibited depolarization following oocyte injection with oxalate in the absence of extracellular Cl−. This Na+- and divalent cation-independent current might represent species-specific, electrogenic oxalate/OH− exchange by mouse slc26a6 or an associated endogenous protein. Indeed, electrogenic oxalate/OH− exchange in rabbit renal brush border membrane vesicles (BBMV) is inhibited only partially by Cl− (Kuo & Aronson, 1996). Alternatively (but not exclusively), mouse slc26a6 but not human SLC26A6 might express an intrinsic oxalate-permeable leak conductance or induce an oocyte conductance, perhaps related to the conductive oxalate transport of rabbit ileal BBMV (Freel et al. 1998) detected along with the previously described oxalate/anion exchange of BBMV (Knickelbein et al. 1986). Indeed, mouse slc26a3 expression is characterized by a large, apparently intrinsic, stoichiometrically uncoupled anion conductance greatly stimulated by bath Cl− removal (Shcheynikov et al. 2006). Uncoupled, intrinsic anion conductance is also a property of trout Cl−/HCO3− exchanger slc4a1 (Martial et al. 2006, 2007). The Cl−-independent current, regardless of mechanism, could reflect such intracellular consequences of oxalate injection as phospholipase A2 activation or mitochondrial toxicity from injected oxalate (Cao et al. 2004; McMartin & Wallace, 2005). Cytosolic and/or organellar precipitation of calcium oxalate might also contribute, but injection of EGTA or BAPTA (estimated 5 mm) has no evident effect on resting oxalate efflux from oocytes expressing either mouse slc26a6 or human SLC26A6 (not shown).

Physiological implications of species-specific properties of oxalate/Cl− exchange by human SLC26A6

The low luminal Cl− present in the intestinal lumen is likely to reflect the action of apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange mediated by SLC26A3 and, to a lesser degree, SLC26A6. The low extracellular Cl− affinity of human SLC26A6 strongly suggests that SLC26A6-mediated oxalate secretion is not saturated with respect to luminal Cl− in the human intestine. The comparatively high affinity for extracellular Cl− of mouse slc26a6 strongly suggests, in contrast, that murine intestinal oxalate secretion is tonically saturated with respect to luminal Cl−. In addition, whereas the intracellular negative potential across the enterocyte apical membrane provides an electrical driving force favouring oxalate secretion by mouse slc26a6, oxalate secretion by human SLC26A6 appears to be insensitive to electrical driving force. Oxalate/OH− exchange in rat renal cortical brush border membrane vesicles was observed to be voltage-insensitive (Yamakawa & Kawamura, 1990), whereas oxalate/OH− exchange in rabbit ileal brush border membrane vesicles was electrogenic (Kuo & Aronson, 1996).

Taken together, the properties of high Cl− affinity and electrogenicity of oxalate/Cl− exchange by mouse slc26a6 favour efficient intestinal oxalate secretion. In contrast, the low Cl− affinity and apparent electroneutrality of oxalate/Cl− or oxalate/anion exchange by human SLC26A6 suggest an intestinal oxalate secretion process that is inefficient relative to that of mouse intestine. This relative inefficiency of human SLC26A6-mediated intestinal oxalate secretion is much less marked in the S3 segment of the proximal tubule, with its luminal [Cl−] of ≳ 115 mm. These differences in Cl− affinity and in electrogenicity are each consistent with the species-specific differences in susceptibility to nephrolithiasis, high in human and low in mouse. The coincidence of the human SLC26A6 K1/2 for extracellular Cl− and the intestinal luminal [Cl−] indicates that human SLC26A6 Cl− affinity is well positioned as a target for physiological regulation. Agents designed to increase Cl− affinity of human SLC26A6 would increase enterocyte oxalate secretion and potentially attenuate hyperoxaluria.

The low extracellular Cl− affinity of human SLC26A6, together with the measured intestinal luminal [Cl−] of the jejunal lumen, suggest that increased intestinal luminal [Cl−] might enhance intestinal oxalate secretion. However, the ability of increased dietary Cl− intake to elevate luminal intestinal Cl−, though unknown, is of low likelihood. Increased dietary Cl− might counterproductively increase hypercalciuria, insofar as dietary substitution of bicarbonate for chloride has reduced hypercalciuria in a small group of hypercalciuric patients (Muldowney et al. 1994), and has also enhanced the hypocalciuric effect of hydrochlorthiazide (Frassetto et al. 2000).

Human SLC26A6 as a risk modifier gene for nephrolithiasis

The human SLC26A6 gene has only a single cSNP among nine curated SNPs in the NCBI database as of July 2007. The V185M variant of SLC26A6 is a common one, with an allele frequency of 0.134, and an estimated population frequency of homozygotes of nearly 2%. The variant has been found in both short and long N-terminal isoforms (Chernova et al. 2005) of SLC26A6. Compared to the most common SLC26A6 polypeptide, the V185M variant shows slightly reduced 36Cl− influx driven by injected oxalate, slightly reduced [14C]oxalate uptake, and a Cl− concentration dependence shifted slightly towards higher [Cl−] at concentrations physiologically relevant for the human intestinal lumen. This small shift might reduce intestinal oxalate secretion enough in the setting of urinary calcium oxalate supersaturation to accelerate lithogenesis. The V185M polymorphism and others in the SLC26A6 gene might thus associate with increased prevalence or severity of nephrolithiasis and/or nephrocalcinosis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants RO1 DK-43495 to S.L.A. and T32 DK-07199 to J.S.C. (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Renal Training Grant). We thank Drs Minna Kujala, Hannes Lohi and Juha Kere (University Helsinki) for antibody to human SLC26A6.

Supplementary material

Online supplemental material for this paper can be accessed at: http://jp.physoc.org/cgi/content/full/jphysiol.2007.143222/DC1 and http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/suppl/10.1113/jphysiol.2007.143222

References

- Cao LC, Honeyman TW, Cooney R, Kennington L, Scheid CR, Jonassen JA. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a primary event in renal cell oxalate toxicity. Kidney Int. 2004;66:1890–1900. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernova MN, Jiang L, Friedman DJ, Darman RB, Lohi H, Kere J, Vandorpe DH, Alper SL. Functional comparison of mouse slc26a6 anion exchanger with human SLC26A6 polypeptide variants: differences in anion selectivity, regulation, and electrogenicity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8564–8580. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411703200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernova MN, Jiang L, Shmukler BE, Schweinfest CW, Blanco P, Freedman SD, Stewart AK, Alper SL. Acute regulation of the SLC26A3 congenital chloride diarrhoea anion exchanger (DRA) expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol. 2003;549:3–19. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.039818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe FL, Evan A, Worcester E. Kidney stone disease. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2598–2608. doi: 10.1172/JCI26662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fordtran JS, Locklear TW. Ionic constituents and osmolality of gastric and small-intestinal fluids after eating. Am J Digestive Dis. 1966;11:503–521. doi: 10.1007/BF02233563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frassetto LA, Nash E, Morris RC, Jr, Sebastian A. Comparative effects of potassium chloride and bicarbonate on thiazide-induced reduction in urinary calcium excretion. Kidney Int. 2000;58:748–752. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freel RW, Hatch M, Green M, Soleimani M. Ileal oxalate absorption and urinary oxalate excretion are enhanced in Slc26a6 null mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G719–G728. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00481.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freel RW, Hatch M, Vaziri ND. Conductive pathways for chloride and oxalate in rabbit ileal brush-border membrane vesicles. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1998;275:C748–C757. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.3.C748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AH, Freel RW, Hatch M. Serum oxalate in human beings and rats as determined with the use of ion chromatography. J Lab Clin Med. 2004;144:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch M, Cornelius J, Allison M, Sidhu H, Peck A, Freel RW. Oxalobacter sp. reduces urinary oxalate excretion by promoting enteric oxalate secretion. Kidney Int. 2006;69:691–698. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch M, Freel RW, Vaziri ND. Regulatory aspects of oxalate secretion in enteric oxalate elimination. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10(Suppl. 14):S324–S328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes RP, Goodman HO, Assimos DG. Contribution of dietary oxalate to urinary oxalate excretion. Kidney Int. 2001;59:270–276. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe B, Beck B, Gatter N, von Unruh G, Tischer A, Hesse A, Laube N, Kaul P, Sidhu H. Oxalobacter formigenes: a potential tool for the treatment of primary hyperoxaluria type 1. Kidney Int. 2006;70:1305–1311. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings ML, Adame MF. Characterization of oxalate transport by the human erythrocyte band 3 protein. J Gen Physiol. 1996;107:145–159. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.1.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z, Asplin JR, Evan AP, Rajendran VM, Velazquez H, Nottoli TP, Binder HJ, Aronson PS. Calcium oxalate urolithiasis in mice lacking anion transporter Slc26a6. Nat Genet. 2006;38:474–478. doi: 10.1038/ng1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z, Grichtchenko II, Boron WF, Aronson PS. Specificity of anion exchange mediated by mouse Slc26a6. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33963–33967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202660200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knickelbein RG, Aronson PS, Dobbins JW. Oxalate transport by anion exchange across rabbit ileal brush border. J Clin Invest. 1986;77:170–175. doi: 10.1172/JCI112272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo SM, Aronson PS. Pathways for oxalate transport in rabbit renal microvillus membrane vesicles. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15491–15497. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.26.15491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamprecht G, Baisch S, Schoenleber E, Gregor M. Transport properties of the human intestinal anion exchanger DRA (down-regulated in adenoma) in transfected HEK293 cells. Pflugers Arch. 2005;449:479–490. doi: 10.1007/s00424-004-1342-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martial S, Guizouarn H, Gabillat N, Pellissier B, Borgese F. Consequences of point mutations in trout anion exchanger 1 (tAE1) transmembrane domains: evidence that tAE1 can behave as a chloride channel. J Cell Physiol. 2006;207:829–835. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martial S, Guizouarn H, Gabillat N, Pellissier B, Borgese F. Importance of several cysteine residues for the chloride conductance of trout anion exchanger 1 (tAE1) J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:70–78. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMartin KE, Wallace KB. Calcium oxalate monohydrate, a metabolite of ethylene glycol, is toxic for rat renal mitochondrial function. Toxicol Sci. 2005;84:195–200. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mio K, Kubo Y, Ogura T, Yamamoto T, Arisaka F, Sato C. The motor protein prestin is a bullet-shaped molecule with inner cavities. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1137–1145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702681200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muldowney FP, Freaney R, Barnes E. Dietary chloride and urinary calcium in stone disease. QJM. 1994;87:501–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osswald H, Hautmann R. Renal elimination kinetics and plasma half-life of oxalate in man. Urologia Intis. 1979;34:440–450. doi: 10.1159/000280294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo D, Cronise BL, Snyder RB, Knauf PA. A novel method to differentiate between ping-pong and simultaneous exchange kinetics and its application to the anion exchanger of the HL60 cell. J Gen Physiol. 1992;100:825–846. doi: 10.1085/jgp.100.5.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribaya JD, Gershoff SN. Factors affecting endogenous oxalate synthesis and its excretion in feces and urine in rats. J Nutr. 1982;112:2161–2169. doi: 10.1093/jn/112.11.2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaechinger TJ, Oliver D. Nonmammalian orthologs of prestin (SLC26A5) are electrogenic divalent/chloride anion exchangers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:7693–7698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608583104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shcheynikov N, Wang Y, Park M, Ko SB, Dorwart M, Naruse S, Thomas PJ, Muallem S. Coupling modes and stoichiometry of Cl−/HCO3− exchange by slc26a3 and slc26a6. J Gen Physiol. 2006;127:511–524. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AK, Chernova MN, Shmukler BE, Wilhelm S, Alper SL. Regulation of AE2-mediated Cl− transport by intracellular or by extracellular pH requires highly conserved amino acid residues of the AE2 NH2-terminal cytoplasmic domain. J Gen Physiol. 2002;120:707–722. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor EN, Curhan GC. Oxalate intake and the risk for nephrolithiasis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2198–2204. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007020219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnberg LA, Bieberdorf FA, Morawski SG, Fordtran JS. Interrelationships of chloride, bicarbonate, sodium, and hydrogen transport in the human ileum. J Clin Invest. 1970a;49:557–567. doi: 10.1172/JCI106266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnberg LA, Fordtran JS, Carter NW, Rector FC., Jr Mechanism of bicarbonate absorption and its relationship to sodium transport in the human jejunum. J Clin Invest. 1970b;49:548–556. doi: 10.1172/JCI106265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesson JA, Johnson RJ, Mazzali M, Beshensky AM, Stietz S, Giachelli C, Liaw L, Alpers CE, Couser WG, Kleinman JG, Hughes J. Osteopontin is a critical inhibitor of calcium oxalate crystal formation and retention in renal tubules. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:139–147. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000040593.93815.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Q, Welch R, Mercado A, Romero MF, Mount DB. Molecular characterization of the murine Slc26a6 anion exchanger: functional comparison with Slc26a1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;283:F826–F838. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00079.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakawa K, Kawamura J. Oxalate: OH exchange across rat renal cortical brush border membrane. Kidney Int. 1990;37:1105–1112. doi: 10.1038/ki.1990.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi T, Quillard M, Takahashi S, Nguyen-Khoa M. Oxalate removal by daily dialysis in a patient with primary hyperoxaluria type 1. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:2407–2411. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.12.2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Du GG, Anderson CT, Keller JP, Orem A, Dallos P, Cheatham M. Analysis of the oligomeric structure of the motor protein prestin. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:19916–19924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.