Abstract

This paper presents an account of past and current research on spiny inverted neurons – alternatively also known as ‘inverted pyramidal neurons’– in rats, rabbits and cats. In our laboratory, we have studied these cells with a battery of techniques suited for light and electron microscopy, including Nissl staining, Golgi impregnation, dye intracellular filling and axon retrograde track-tracing. Our results show that spiny inverted neurons make up less than 8.5 and 5.5% of all cortical neurons in the primary and secondary rabbit visual cortex, respectively. Infragranular spiny inverted neurons constitute 15 and 8.5% of infragranular neurons in the same animal and areas. Spiny inverted neurons congregate at layers V–VI in all studied species. Studies have also revealed that spiny inverted neurons are excitatory neurons which furnish axons for various cortico-cortical, cortico-claustral and cortico-striatal projections, but not for non-telencephalic centres such as the lateral and medial geniculate nuclei, the colliculi or the pons. As a group, each subset of inverted cells contributing to a given projection is located below the pyramidal neurons whose axons furnish the same centre. Spiny inverted neurons are particularly conspicuous as a source of the backward cortico-cortical projection to primary visual cortex and from this to the claustrum. Indeed, they constitute up to 82% of the infragranular cells that furnish these projections. Spiny inverted neurons may be classified into three subtypes according to the point of origin of the axon on the cell: the somatic basal pole which faces the cortical outer surface, the somatic flank and the reverse apical dendrite. As seen with electron microscopy, the axon initial segments of these subtypes are distinct from one another, not only in length and thickness, but also in the number of received synaptic boutons. All of these anatomical features together may support a synaptic-input integration which is peculiar to spiny inverted neurons. In this way, two differently qualified streams of axonal output may coexist in a projection which arises from a particular infragranular point within a given cortical area; one stream would be furnished by the typical pyramidal neurons, whereas spiny inverted neurons would constitute the other source of distinct information flow.

Keywords: axon initial segment, cerebral organization, corticofugal projections, improperly orientated pyramidal neurons, infragranular layers, inverted neurons, inverted pyramidal neurons, projection cells.

Introduction

Cerebral cortical neurons are heterogeneous in many aspects. They are typically classified as being either spiny or aspiny, based on morphological characteristics (Globus & Scheibel, 1967; Jones & Powell, 1970; Peters, 1971). The use of biochemical and biophysical procedures has clearly demonstrated that cells within each group not only share morphological features, but also have similar chemical and physiological properties. Spiny neurons are of an excitatory nature and most have extrinsic axons (i.e. axons that project outside the cortical area where their somata are located). These cells employ glutamate as a neurotransmitter. Most of their axons enter the white matter, where they run for long distances to reach other cortical areas and subcortical centres. By contrast, aspiny neurons are inhibitory, and most of their axons are intrinsic, i.e. they use gamma-amino-butyric acid (GABA) as a neurotransmitter and their axons remain within the cortical area in which the parent cell soma lies.

In turn, the spiny and the aspiny cell groups consist of several neuron subgroups. Pyramidal neurons are by far the largest subgroup within the group of spiny cells. These neurons can be further subdivided into subpopulations which share anatomical, chemical and electrophysiological characteristics. For instance, a general feature of cortical organization is that within every cortical area, each pyramidal cell subpopulation providing axons to a given target has a specific morphology and layer location. So, in layer VI of the cat visual cortex, the pyramidal cells that project to the claustrum differ from those that project to the lateral geniculate nucleus (Katz, 1987; Hübener et al. 1990); in layer V of the rat visual cortex, the pyramidal neurons that project to the superior colliculus and pons are distinct from those that project through the callosum to the contralateral cortex (Hallman et al. 1988; Hübener & Bolz, 1988). The distinct dendrite distribution characteristic of each of these pyramidal cell subpopulations would therefore allow sampling of a unique set of afferents. In this way, different types of information could be sent from a given point in the cortex to disparate targets (Katz, 1987; Hallman et al. 1988; Hübener & Bolz, 1988; De Lima et al. 1990; Hübener et al. 1990).

However, cortical projections can also arise from spiny cells other than typical pyramidal neurons. These include the ‘modified’ pyramidal neurons, such as spiny neurons which have no apical dendrite, e.g. the stellate cells of low layer III and layer IV. Despite being excitatory in nature, most of these cells are intrinsic. Their axons go to layer III pyramidal cells above them. Other examples of ‘modified’ spiny cells are those which have forked and even double apical dendrites. These cells lie within layer II and layer VI. Some spiny neurons of layer VI have apical dendrites which emerge at an angle from the cell soma and then bend themselves straight in a direction perpendicular to the cortical surface. This is to avoid somata sited above them but within the same layer VI cell column. Yet another class of modified pyramidal neurons are the layer V spiny neurons that have a long basal dendrite (‘tape root’) in addition to other basal dendrites and a longer apical dendrite in the usual position (Scheibel & Scheibel, 1978; Yamamoto et al. 1987).

Finally, the polymorphic-cell subgroup (Ramón y Cajal 1891, 1911; Tömböl, 1984; DeFelipe & Jones, 1988) consists of spiny neurons in layers V and VI with morphologies which are utterly distinct from those of the typical and modified pyramidal neurons. The polymorphic-cell subgroup encompasses at least triangular, fusiform and horizontal cells. Other polymorphic neurons have a peculiar ‘inverted’ dendrite polarization; these may integrate axonal inputs which are significantly distinct from those converging upon any other spiny neuron lying in the layer and projecting to the same target. The latter subset of polymorphic neurons is made up of the so-called spiny inverted neurons, which are usually referred to as inverted pyramidal neurons.

Spiny inverted neurons

Santiago Ramón y Cajal (whose centenary of winning the Nobel Prize was celebrated in 2006) noticed that ‘cellules sans tige protoplasmatique externe’ (literally ‘cells without an external protoplasmic stem’ or, in other words, cells without an apical/major dendrite going towards the pia) are very conspicuous in infragranular layers of the cat temporal cortex. Ramón y Cajal also reported that such nerve cells had a thick and descendent protoplasmic expansion, i.e. a major dendrite orientated towards the white matter. He also wrote that his study of such cells was still unfinished (see p. 634 and fig. 402 in Ramón y Cajal, 1911, vol. II). More than 50 years later, Van der Loos carried out the first study which focused in particular on these neurons. He called them ‘improperly oriented pyramidal neurons’ because of the atypical direction of their major dendrite. The improperly orientated neurons encompass all spiny cells with a major dendrite which is abpially orientated (Van der Loos, 1965). (For references on other studies of the époque focusing on spiny inverted neurons under this or other names, see p. 426 in Bueno-Lopez et al. 1991.)

Curiously, these spiny neurons have on occasion been considered to be a product of cortical malformations. This supposition was based on their conspicuous misplacement in the cortex of reeler-mice (Pinto-Lord & Caviness, 1979; Landrieu & Goffinet, 1981) or other abnormal animals (Williams et al. 1975; Lund, 1978; Bordalier et al. 1986; Takada et al. 1988). Their presence in epileptic temporal cortex has even led to the suggestion that there is a link between these cells and epilepsy (Belichenko et al. 1992).

In our laboratory, we have spent many years studying spiny neurons with a major dendrite orientated towards the white matter by means of a variety of methods including Golgi impregnation, Nissl staining, dye intracellular filling, axon retrograde track-tracing and electron microscopy. Taken together, our results corroborate those of others in supporting the idea that these neurons are a functional element of the normal cerebral cortex. First, during normal ontogeny spiny inverted neurons develop over time in parallel with typical pyramidal neurons (Fig. 1) (Marin-Padilla, 1972; Miller, 1988; Reblet et al. 1996; Blanco-Santiago, 2003; J.L.B.-L. and C.R., unpublished data). Secondly, spiny inverted neurons have been found in the normal postnatal cerebral cortex throughout the mammalian series, including humans (Golgi, 1873; Ramón y Cajal, 1911; O’Leary & Bishop, 1938; Van der Loos, 1965; Globus & Scheibel, 1967; Landrieu & Goffinet, 1981; Ferrer et al. 1986a,b; Miller, 1988; Cajal-Agüeras et al. 1989; Bueno-Lopez et al. 1991; Reblet et al. 1992; Van Brederode & Snyder, 1992; Arimatsu et al. 1994; Einstein, 1996; Matsubara et al. 1996; Zhong-Wei & Deschenes, 1997; Prieto & Winer, 1999; Qi et al. 1999; Karayannis et al. 2007). However, the incidence of spiny inverted neurons may be not only species-specific, but also area-specific. Thus, neurons with inverted soma profiles make up 5.5% of all Nissl-stained neurons in layers II–VI of the rabbit cerebral cortex (Globus & Scheibel, 1967). This proportion is 8.5% in the striate cortex of the same animal (Nissl-staining; Bueno-Lopez et al. 1991). The incidence of neurons with inverted soma outlines is nonetheless somewhat less (1%) in the cerebral cortex of rats (Nissl-staining; Parnavelas et al. 1977) and monkeys (monoclonal antibody SMI-32 immunostaining; Qi et al. 1999). In our laboratory, we also found a lower percentage in the cat visual cortex (Nissl-staining; 1.5%, areas 17, 18, 19; 4.5%, area 21a; J.L.B.-L. and C.R., unpublished data). Nevertheless, spiny inverted neurons congregate at layers V–VI in all studied species. Neurons with inverted soma profiles constitute 15 and 8.5% of all Nissl-stained neurons in layers V–VI of the rabbit primary and secondary visual cortex, respectively (Bueno-Lopez et al. 1991).

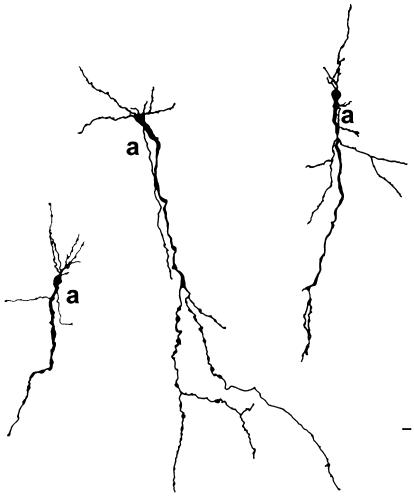

Fig. 1.

Camera-lucida drawings of three immature inverted neurons in layer VI of the rabbit temporal cortex. The cells were impregnated by the Golgi-Stensaas procedure on postnatal day 1. Axons are marked by the letter ‘a’. All of them arise from the main (apical) dendrite, which is orientated towards the white matter. Note the growth beads in dendrites and axons. These cells will most probably be spiny when mature. This kind of spiny inverted cell is also typically referred to as an ‘inverted pyramidal neuron’ in the literature. Scale bar: 15 µm. This bar is at the border of layer VI with the white matter.

Chemical and functional nature

As mentioned above, spiny inverted neurons have frequently been referred to as ‘inverted pyramidal neurons’. Nonetheless, the term ‘inverted pyramidal neuron’ is misleading, as not all of these neurons have a pyramidal-shaped soma. Most commonly, the term has been used to refer to inverted neurons of spiny nature. Yet it can also be applied to other sorts of cells. For instance, some inverted pyramidal neurons resemble Martinotti cells. Martinotti cells are intriguing inverted cells which can be found in any cortical layer, with the exception of layer I. The axon of a Martinotti cell typically ascends up to layer I, where a horizontal axonal cluster is often formed before ending in spiny synaptic boutons. The dendrites of Martinotti cells are aspiny or poorly covered with spines. With Golgi impregnations we can accurately detect spiny inverted pyramidal neurons, whereas not all Nissl-stained neurons with an inverted morphology will necessarily be seen as being spiny. The latter also applies to any other staining technique that does not make visible dendritic spines, despite revealing other features which are no less important for a neuron to be characterized, e.g. axon-projection targets, cell-synthesized neurotransmitters and other substances expressed by the nerve cell. Thus, in layer VI of the rabbit cortex, cells with an inverted morphology that present vasoactive intestinal polypeptide immunoreactivity have been reported (Cajal-Agüeras et al. 1989). In the rat somatosensory cortex, another subset of inverted infragranular neurons presents calcium binding protein immunoreactivity (Van Brederode et al. 1991; Fukuda & Kosaka, 2003). Some inverted cells located in layer II of the rat cerebral cortex exhibit diaphorase immunoreactivity (Gabbott & Bacon, 1995). In our laboratory, we have found diaphorase-immunoreactive inverted cells in layer VI of the rabbit cortex (C.R. and J.L.B.-L., unpublished data). Finally, GAD67–GFP-expressing neurons include inverted neurons in layer VI of mice and rats (Jin et al. 2001). Regardless, the fact that cortical neurons express a variety of immunoreactive substances according to different studies does not necessarily mean that they should fall into disparate cell subpopulations. Several of the reported proteins may be coexpressed within these cells.

It is most likely that many if not all of the cells referred to in the latter paragraph are aspiny or poorly spiny inhibitory neurons with axons intrinsic to the area where the cell soma lies. Thus, some of the diaphorase-immunoreactive inverted neurons referred to above have a number of spines on their dendrites (Gabbott & Bacon, 1995). Aspiny or poorly spiny inverted neurons (such as those shown in Fig. 2a, cell on the right, and Fig. 3) are GABAergic and therefore of inhibitory nature (Somogyi et al. 1982). However, some inverted cells that express GAD67–GFP in layer VI of mice and rats are heavily spiny (Jin et al. 2001). This feature was attributed to the fact that these cells belonged to a very young animal, and GABAergic neurons can be spiny during development (Jin et al. 2001). By contrast, many inverted pyramidal neurons in adult animals have both dendrite spines and long-range axon projections. Thus, the inverted pyramidal morphology of a cortical neuron is an attribute that is shared by cells that may be either spiny or aspiny, excitatory or inhibitory, with extrinsic or intrinsic axon projections. Further studies of various cells with reverse dendrite polarization are clearly required. In particular, studies which would correlate neuron morphology with specific molecular markers and axon projections would be helpful.

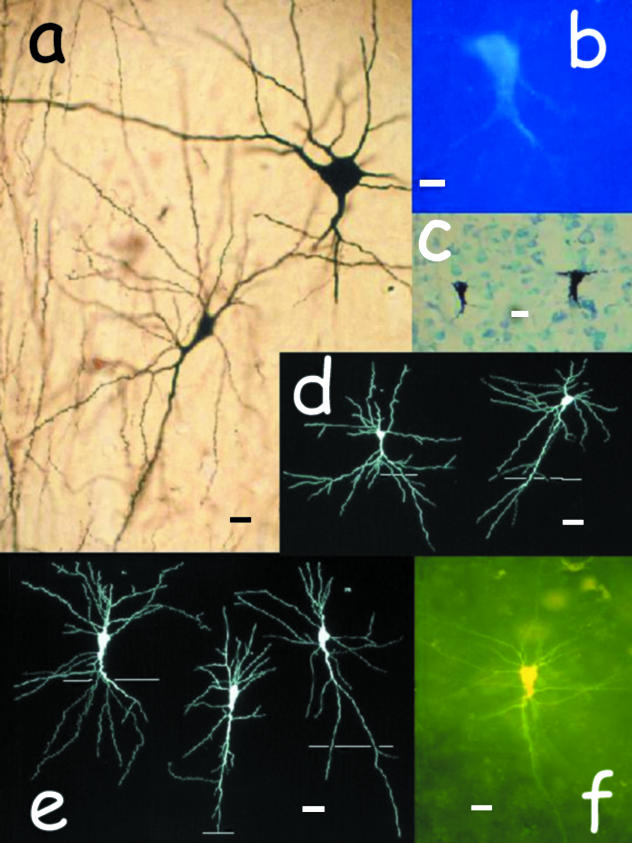

Fig. 2.

Infragranular inverted neurons in the rabbit and cat adult cerebral cortex. All of them are spiny inverted neurons, as defined in this paper, except for the cell on the right in (a). Notice that the axon arises from the apical dendrite in many cells. Notice also that some apical dendrites are bifurcated. (a) The cell on the left is a fully fledged spiny inverted neuron. Notice the dendrite spines. The cell on the right, which is bigger than its companion, is a mature aspiny neuron with inverse dendrite polarization, possibly a basket cell. Both neurons lie in layer V of adult cat area 18. Golgi impregnation. Scale bar: 20 µm. (b) Long-range projecting, inverted neuron of the layer V/VI border, adult rabbit secondary visual cortex. This fully fledged cell was retrogradely labelled after fluorogold injection into the ipsilateral primary visual cortex. Scale bar: 15 µm. (c) Two long-range projecting, mature inverted neurons retrogradely labelled with WGA-HRP in layer V of adult cat posterolateral lateral suprasylvian sulcus (area PLLS). The histological section was Nissl counterstained. Tracer injection was delivered into ipsilateral area 17. Scale bar: 20 µm. (d) Camera-lucida illustration of two Golgi-impregnated mature spiny inverted neurons in the adult cat primary visual cortex. Notice the forked apical dendrite of the cell on the left. Scale bar: 25 µm. In this and the next illustration, slim horizontal bars indicate the border of layer VI with the white matter. (e) Camera-lucida drawing of three Golgi-impregnated mature spiny inverted neurons in layer VI of the adult cat primary visual cortex. Scale bar: 20 µm. (f) Long-range projecting, spiny inverted neuron in layer VI of adult cat area 18. This mature cell was retrogradely labelled after an injection of rhodamine latex beads into ipsilateral area 17. Then, in a semi-fixed slice, the cell was filled with Lucifer Yellow delivered through a pipette inserted into the soma under microscopic control. The cell was spiny (not appreciable due to the low magnification). Scale bar: 15 µm.

Fig. 3.

Camera-lucida drawing of the soma and main portions of the dendrites and axon of a Golgi-impregnated neuron with reverse dendrite polarization. This fully fledged neuron was found in layer VI of the adult rat primary visual cortex. This neuron is a good example of an aspiny inverted pyramidal neuron, which is presumably an interneuron of inhibitory nature. Notice the apical dendrite pointing towards the white matter. All dendrites were short and thin. No spine was observed on them. Arrow points to the axon. Scale bar: 20 µm.

In the following, we focus on fully fledged spiny inverted neurons. For the sake of clarity and greater precision, we use the term ‘spiny inverted neuron’ for any inverted cell that has copious dendrite spines and a cell-body outline resembling that of an inverted pyramid, an inverted pear, or even an oval or round balloon (Fig. 2). In doing so, we are aware that the term ‘inverted pyramidal neuron’ is somewhat confusing. Indeed, it is still uncertain if spiny inverted neurons and typical pyramidal neurons belong to the same original cell group which subsequently become oppositely orientated, or if they arise from strictly different cell-precursor types during ontogeny (Marin-Padilla, 1972 and personal communication). Cellular markers for spiny neurons have become commercially available in recent years. These markers are not only useful for cell classification, but also hold the promise of facilitating a greater understanding of neuron development (for a review, see Molnar & Cheung, 2006). For recent reviews on the neuronal subtype specification of projection neurons in the cerebral cortex, and the cell-cycle control and cortical development, see Molyneaux et al. (2007) and Dehay & Kennedy (2007), respectively.

Spiny inverted neurons make up only a fraction of the total population of inverted neurons. As stated above, abundant dendrite spines on spiny inverted neurons clearly distinguish them from other or poorly spiny inverted neurons. However, it must be kept in mind that, at least in our case, we have not always been able unequivocally to detect dendrite spines on all the cells which we have considered to be spiny inverted neurons, in some of our axon retrograde track-tracing experiments in rats, rabbits and cats (Bueno-Lopez et al. 1991; Reblet et al. 1992; Gutierrez-Ibarluzea et al. 1999; Mendizabal-Zubiaga, 2004; C.R. and J.L.B.-L., unpublished data) (Fig. 2b,c). In these experiments, inverted cells were a source for long-range cortico-striatal, cortico-claustral or cortico-cortical projections (Fig. 4). Cortico-striatal and cortico-claustral projections do not arise from GABAergic cells, to the best of our knowledge. A very small percentage of the long-range cortico-cortical projections arise from GABAergic-cells in the cerebral cortex of the rat (McDonald & Burkhalter, 1993; Gonchar et al. 1995), mouse (Tomioka et al. 2005) and cat (Fabri & Manzoni, 2004). Long-range GABAergic cortico-cortical projections have not been found in rabbits (Gomez-Urquijo et al. 2000). Hence, we cannot be absolutely sure of the excitatory character of some inverted neurons with long-range cortico-cortical projection, which we retrogradely labelled in our axon track-tracing experiments. In order to quantify this uncertainty, we directly examined the GABAergic nature of the retrogradely labelled inverted neurons as frequently as possible, i.e. in every experiment in which tissue fixation and other technical constraints were compatible with GABA immunocytochemistry. We also checked some Golgi-impregnated spiny inverted neurons as well (n = 17). For this purpose, we employed an anti-GABA monoclonal antibody (Matute & Streit, 1986) on thick and semithin cell-body sections of either retrogradely labelled or Golgi-impregnated cells that were randomly sampled. Unfortunately, we kept no detailed numerical record of the many retrogradely labelled inverted neurons which were checked in this way. We were simply satisfied with the qualitative outcome of the checks. Without exception, the outcome all of these tests was negative. So we can safely assume that all long-range projections and spiny inverted neurons identified in our experiments were not GABAergic (Golgi impregnation: Bueno-Lopez et al. 1991; Mendizabal-Zubiaga, 2004; C.R. and J.L.B.-L., unpublished data; dye intracellular filling: Reblet et al. 1993; Mendizabal-Zubiaga, 2004; C.R. and J.L.B.-L., unpublished data; axon retrograde track-tracing techniques: Bueno-Lopez et al. 1991; Reblet et al. 1992; Gutierrez-Ibarluzea et al. 1999; C.R. and J.L.B.-L., unpublished data). This assumption is further reinforced by electron microscopic examination of spiny inverted neurons in the rat cerebral cortex (see below and Mendizabal-Zubiaga, 2004). This supposition is further corroborated by the finding that latexin-positive inverted cells of layers V and VI of the rat cerebral cortex are glutamatergic (Arimatsu et al. 1999).

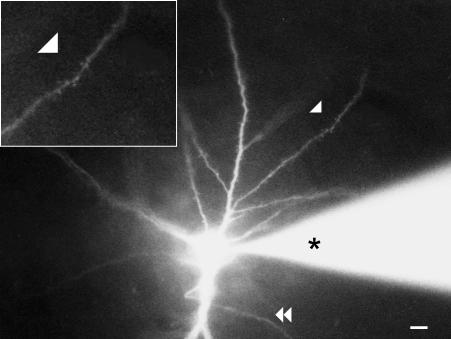

Fig. 4.

Photomicrograph of a mature spiny inverted neuron of layer V of adult cat area 18. The cell was labelled by axon retrograde transport of rhodamine latex beads injected into ipsilateral area 17. Then the cell was filled with Lucifer Yellow through a pipette (*) inserted into the cell soma. Notice the forked apical dendrite. Arrowhead shows dendrite spines, some of which are magnified in the inset. Double arrowhead points to the cell axon. The axon comes out from the apical dendrite, which is orientated towards the white matter (not seen). Scale bar: 10 µm.

Light–microscopy morphology

Under light microscopy, spiny inverted neurons very closely resemble the typical pyramidal neurons in many aspects. However, closer inspection reveals that, apart from the distinctive features described in the following, spiny inverted neurons have a more delicate general appearance than typical pyramidal neurons.

Spiny inverted neurons can be seen as a heterogeneous cell collection (Figs 1–7) (Bueno-Lopez et al. 1991; Reblet et al. 1992, 1993; Gutierrez-Ibarluzea et al. 1999; Mendizabal-Zubiaga, 2004; C.R. and J.L.B.-L., unpublished data). The typical diameter of the cell soma of an archetypical spiny inverted neuron is usually within 15–25 µm. The cell soma may be triangular (with the apex facing the white matter), ovoid or round. The major dendrite characteristically emerges from the soma side that faces the white matter. Then the apical/major dendrite may follow the cortical radial axis or obliquely deviate from it. Sometimes it is the cell soma whose major axis is orientated obliquely, and then the apical dendrite bends down in order to follow the cortical radial axis. The apical dendrite shaft softly winds along its course. This snaking course is clearly distinct from the straightforward line of the apical dendrite of the typically orientated pyramidal neuron. The apical dendrite shaft of a spiny inverted neuron may fork into two thinner dendrite shafts (Fig. 2d, cell on the left; Fig. 4). During its path towards the white matter, the apical dendrite or its subsequently thinner shafts gives rise to several dendrite branches. These branches are softly curled too but thinner than the main dendrite. They follow a descending oblique course. They may be terminal or ramify up to fourth-order branches. In turn, the apical dendrite may end either taping or sprouting into a thin-dendrite tuft. Regardless, the apical dendrite may enter the white matter, in particular when the cell soma lies in layer VI. Up to eight basal dendrites emerge from the somatic end facing the cortical outside. One of these basal dendrites may proceed directly to the overlying cortex. All basal dendrites branch out into secondary and even tertiary dendrites. The basal dendrite is never longer than its apical counterpart. The first portions of the apical and basal dendrites are aspiny. The aspiny portion of the apical dendrite may even continue after the first dendrite branching. The remaining dendrite surface is richly covered with spines.

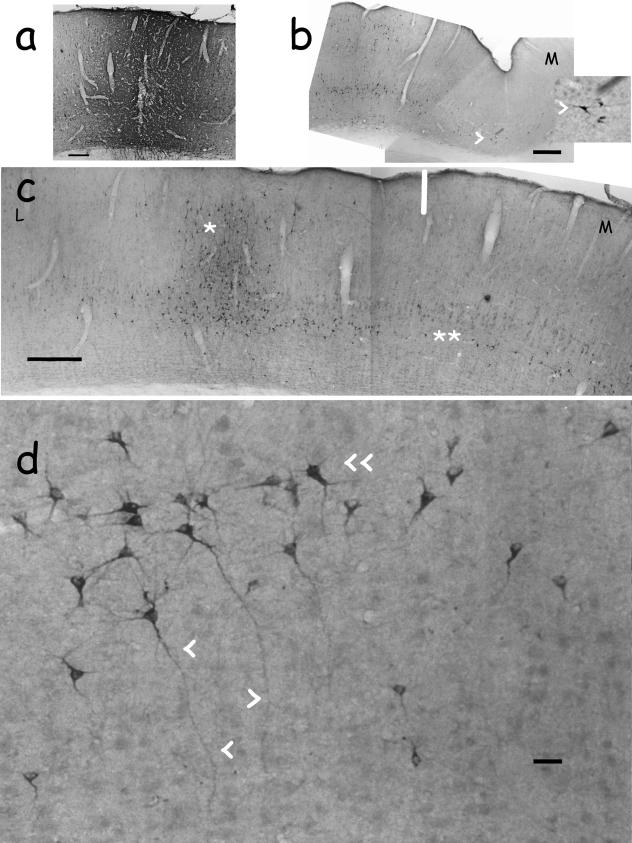

Fig. 7.

Photomicrographs of mature projection neurons, retrogradely labelled with cholera toxin, fraction b (CTb) after injections into the adult rabbit primary visual cortex, ipsilateral to the injections. Arrowheads point to distinctively labelled inverted neurons, though not every labelled inverted neuron is indicated in this way. All of these labelled inverted neurons are presumably spiny inverted neurons, as defined in this paper. All sections are coronal. M: medial. L: lateral. (a) Tracer injection into the primary visual cortex. Notice CTb diffusion within the grey matter. (b) Labelling at the medial sulcus between the primary visual cortex and the retrosplenial cortex. Notice the horizontal orientation of the labelled inverted neurons (inset). (c) The vertical line indicates the transition between the primary and secondary visual cortex. This was delimitated by observing Nissl-stained, consecutive rostral and caudal sections. The single asterisk marks a clear-cut column of discrete labelling across layers II–VI of the lateromedial field of the secondary visual cortex, rostral to the tracer injection site. The double asterisk marks an extended band of retrogradely labelled cells at the layer V/VI border of both the primary and the secondary visual cortex, rostral to the tracer injection site. Notice that labelled inverted neurons mainly lie in layers V–VI in the clear-cut column. Most labelled cells are inverted neurons in the extended band. (d) High-magnification image of labelled cells in the extended band of labelling depicted in (c). The distinctive morphologies of the spiny inverted neurons are apparent, not all of them being clearly ‘pyramidal’. Some of them have forked apical dendrites. Scale bars: (a,b) 100 µm; (c) 250 µm; (d) 30 µm.

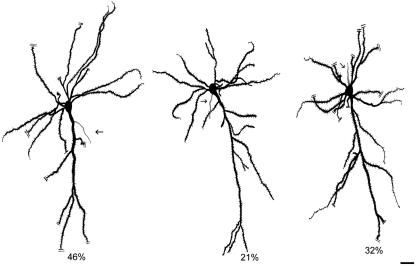

Spiny inverted neurons are odd as well because of the peculiar sites from which the axon arises. These cell sites may be (1) the basal surface of the soma, or even the basal dendrite portion next to the soma, (2) the (lateral) flank of the soma and (3) the apical dendrite, sometimes from a sector more remote from the soma than the emergence site of the first dendrite branching (Landrieu & Goffinet, 1981; Bueno-Lopez et al. 1991). Of the 127 Golgi-impregnated spiny inverted neurons in the occipital and temporal cortices of rabbits which we examined, 37 axons (29.13%) arose from (1), 12 axons (9.45%) from (2) and 78 axons (61.42%) from (3) (Bueno-Lopez et al. 1991). Hence, the most frequent site of axon emergence from rabbit spiny inverted neurons is the apical dendrite. A comparable distribution has been reported for these neurons in rat visual and sensory-motor cortices (Mendizabal-Zubiaga, 2004); of 28 Golgi-impregnated spiny inverted neurons, nine axons (32.14%) emerged from the soma basal surface, six axons (21.43%) from the soma lateral flank and 13 axons (46.43%) from the apical dendrite (Fig. 5). Thus, the probability of axon emergence from the apical dendrite (46.3%) and soma (53.57%) are virtually similar in rats.

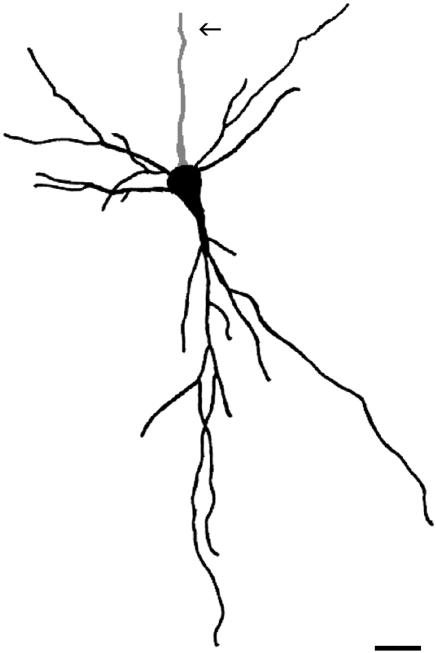

Fig. 5.

Camera-lucida drawings of the soma and main portions of dendrites and axons of three Golgi-impregnated, mature spiny inverted neurons of layer VI of adult rat visual cortex. Notice that the axons (arrows) arise either from the apical dendrite (cell on the left), the basal somatic surface (cell on the right) or the somatic lateral flank (cell in the middle). Percentages indicate the incidence of each cell subtype out of 28 Golgi-impregnated spiny inverted neurons in infragranular layers of rat visual and sensorimotor areas. As seen with subsequent electron microscopy, each axon acquired a myelin sheet during its trajectory towards the white matter or the pia (cell on the right). Scale bar: 20 µm.

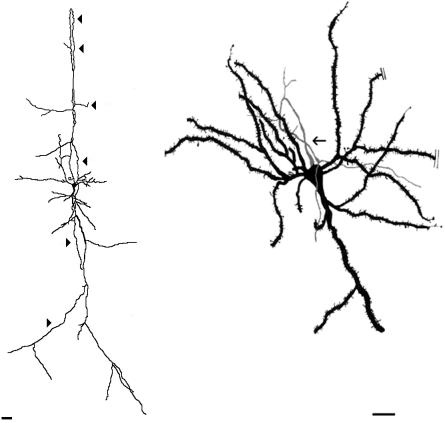

Despite the variety of axon emergence sites, axons from spiny inverted neurons usually run into the white matter. Accordingly, axons that emerge from the apical dendrite or from the lateral flank of the soma lean down to attain a straight or mildly oblique course. The route of those emerging from the basal side of the soma is still more elaborate. They first enter the upper cortex, subsequently to bend their course in an 180° loop to attain the downward direction (Fig. 6). We injected biocytin into the primary visual cortex on postnatal days 1–21 in order to label projection neurons retrogradely in the adjacent secondary visual cortex. This procedure revealed that some of the labelled axons of layer VI spiny inverted neurons proceeded directly from the soma to the upper layers before turning round and proceeding downwards to enter the white matter (C.R. and J.L.B.-L., unpublished data; Fig. 6, cell on the left). However, other axons that arise from the somatic basal surface of spiny inverted neurons to enter the cortex above lose silver impregnation and disappear after less than 100 µm, as shown by the Golgi method (Fig. 5, cell on the right). We do not know if these non-impregnated axons turn round subsequently to course towards the white matter. Nevertheless, these parent cells are very spiny and similar in other aspects to the spiny inverted neurons with 180°-bent axons. No collateral sprouted from the silver-impregnated portion of those axons.

Fig. 6.

Camera-lucida drawings of two spiny inverted neurons with axons firstly going straight towards the pia and then turning around completely, to assume a downward trajectory to the white matter. The immature cell on the left was retrogradely labelled in layer VI of rabbit secondary visual cortex after a biocytin injection into the primary visual cortex at postnatal day 3. The fully fledged cell on the right is a Golgi-impregnated, spiny inverted neuron of adult rat secondary visual cortex. Both axons emerged from the basal pole of the soma. They are marked by arrowheads (left cell), or an arrow (cell on the right). Subsequent electron-microscopy analysis revealed that the axon initial segment of the axons of the Golgi-impregnated neuron on the right and of the neuron depicted to the right in Fig. 5 had similar ultrastructural features. Scale bars: 20 µm.

In contrast, other axons of spiny inverted neurons show abundant collaterals. These may proceed not only from the descending but also from the ascending axon portions. Both types of collaterals run horizontally and obliquely within the cortex for hundreds of micrometres. The oblique collaterals may be descendent or ascendent. We followed some obliquely ascendent collaterals for more than 1 mm up to upper layer III and layer II. In the cat visual cortex (Figs 2a,d–f and 4), the orientation of apical dendrites of a spiny inverted neuron depends on the position of the parent cell within the gyri (C.R. and J.L.B.-L., unpublished data, after Golgi impregnation or Lucifer-Yellow intracellular filling). Thus, the incidence of truly reversed spiny inverted neurons decreased from the top of the gyri to the bottom of the sulci, while that of almost horizontally orientated pyramidal neurons increased. Most axons were found to arise from the apical dendrite or from one of its first branches in cat spiny inverted neurons.

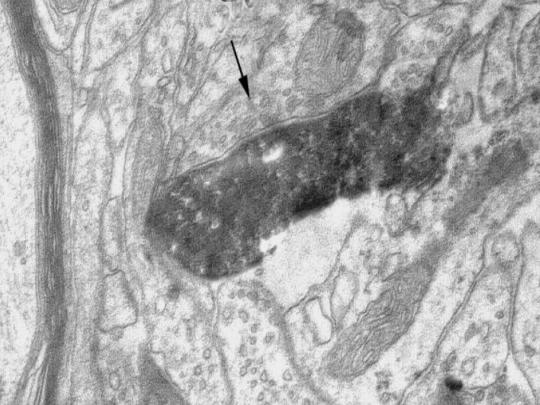

Electron microscopy characteristics

Electron microscopy studies of rat visual and sensory-motor cortex, which were carried out recently in our laboratory, have shown that typical pyramidal neurons and spiny inverted neurons share many but not all ultrastructural features (Mendizabal-Zubiaga, 2004). First, typical pyramidal neurons and spiny inverted neurons do not have nuclear membrane indentations. These indentations are typical of the nuclei of cortical GABAergic interneurons (Peters & Kara, 1985a,b). Secondly, incoming synapses which form on dendrites and soma have comparable distributions for typical pyramidal neurons and spiny inverted neurons. Thus, the synaptic boutons apposed to the spine heads of both cell subgroups have round vesicles and form Gray Type I asymmetric contacts. Synaptic boutons apposed to the cell body and spine–neck membrane have polymorphic vesicles and form Gray Type II symmetric contacts. Synapses made with dendrite shafts may be of both types, symmetric and asymmetric. In the cerebral cortex, this pattern is known to be typical of excitatory neurons (Colonnier, 1968; for reviews see Peters & Kara, 1985a,b). Thirdly, the axonal initial segments of typical pyramidal neurons and spiny inverted neurons receive synaptic contacts which are almost exclusively Gray Type II contacts. The pre- and postsynaptic membranes of these contacts have symmetric densities. The vesicles in the presynaptic boutons are flattened and polymorphic (Fig. 8). These synaptic features are akin to those seen at the axon initial segment of typical pyramidal neurons (DeFelipe & Fariñas, 1992). This is again consistent with the presumptive excitatory nature of the spiny inverted neurons. Synaptic boutons contacting the axon initial segment membrane of typical pyramidal neurons belong to chandelier interneurons (Somogyi, 1977). We suspect that synaptic boutons on the axon initial segment of spiny inverted neurons also belong to chandelier cells, but direct evidence for this is still lacking.

Fig. 8.

Electron microphotograph of a large axon terminal bouton (indicated by arrow) making a Gray Type II symmetric contact with the axon initial segment of a biocytin-filled spiny inverted neuron of layer V of adult rat sensorimotor cortex. Notice the polymorphic vesicles in the terminal bouton. The postsynaptic membrane density is obscured because of biocytin filling the axon initial segment. The electron microscopy image was taken at 15 000×. This synapse exemplifies those observed with electron microscopy at the axon initial segment of 11 mature spiny inverted neurons of adult rat cortex.

Last but not least, we did identify differences in the axon initial segments of typical pyramidal neurons and spiny inverted neurons of the infragranular layers in the rat cortex (Mendizabal-Zubiaga, 2004). We studied the axon initial segments of 11 spiny inverted neurons with unknown axon projections, and five typical pyramidal neurons with cortico-cortical axon projections as identified by biotin dextran amine (BDA) retrograde tract tracing. The length of the axon initial segment of the typical pyramidal neurons remained between 30.5 and 34.0 µm, while its thickness varied between 0.94 and 1.15 µm. In turn, the length of the axon initial segment of spiny inverted neurons ranged between 32.0 and 101.2 µm, and its thickness varied between 0.58 and 1.04 µm. Moreover, the average number of synaptic contacts received by the axon initial segment of spiny inverted neurons was found to be greater than that of the typical pyramidal neurons (24.4 vs. 17.6, respectively). Nonetheless, the range of values was also found to be wider among the spiny inverted neurons. Additionally, analysis of spiny inverted neurons classified in terms of the emergence site of the axon, i.e. the somatic flank, the somatic basal surface or the apical dendrite, revealed that axon initial segments which proceed from the apical dendrite were the shortest, thinnest and less innervated, whereas axon initial segments arising from the somatic flank were the longest, widest and most innervated. Table 1 shows the averages and ranges of all 16 neurons. Despite the limited number of measured cells being insufficient to confer statistical significance, it is a large number for an electron microscopy study. Work is currently in progress in our laboratory to study the extent to which differences in the number of synapses received at the axon initial segment are related to the morphology and type of axon projection of spiny inverted neurons.

Table 1.

Electron microscopy of the axon initial segment of spiny inverted neurons and typical pyramidal neurons in the infragranular layers of the adult rat cortex. Spiny inverted neurons can be further subclassified on the basis of the site of axon emergence, whereas typical pyramidal neurons can be subclassified in terms of cortico-cortical axon projections, as identified by retrograde track tracing of biotin dextran amine. Length and thickness are given in micrometres

| Cell type | Spiny inverted neuron | Cortico-cortically projecting, typical pyramidal neuron | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-classification | Axon, lateral somatic emergence | Axon, basal somatic emergence | Axon, apical dendrite emergence | Projection, ipsilateral from area 18 to area 17 | Projection, contralateral, from area 17 to area 17 |

| Number of cells | 2 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Average length [range] | 95.5 [93.2–97.8] | 60.9 [32.0–101.2] | 38.8 [37.1–45.4] | 31.6 [31.4–31.8] | 31.7 [30.5–34.0] |

| Average thickness [range] | 1.04 [1.04] | 0.83 [0.71–0.96] | 0.6 [0.58–0.62] | 0.99 [0.94–1.05] | 1.07 [0.97–1.15] |

| Average no. of synapses [range] | 34 [31–37] | 26 [21–29] | 15 [11–18] | 21 [20–22] | 15 [15–16] |

Axon-projection targets

Injections of wheat germ agglutinin–horseradish peroxidase (WGA-HRP), fluorogold, fraction b of cholera toxin (CTb), biotin dextran amine (BDA), biocytin and rhodamine latex beads delivered into cortical or subcortical sites in our laboratory revealed that spiny inverted neurons contribute axons not only to cortico-cortical projections, but also to other cortico-telencephalic projections in rats, rabbits and cats. Here, we summarize these findings, which are also represented in Table 2. More can be found in Bueno-Lopez et al. (1991), Reblet et al. (1992) and Gutierrez-Ibarluzea et al. (1999). The results of other studies are reviewed in Prieto & Winer (1999).

Table 2.

Axon projections of spiny inverted neurons in rats, rabbits and cats. We also explored projections from the visual and auditory cortex to the medial and lateral geniculate nuclei, colliculi and pons. Inverted neurons project to these non-telencephalic centres only on very rare occasions

| Ipsilateral cortico-cortical projection | Contralateral cortico-cortical projection | Cortico-claustral projection | Cortico-striatal projection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rats | +/++/+++* | ++/+++* | ++/+++* | Unexplored |

| Rabbits | +/++/+++* | ++/+++* | ++/+++* | + |

| Cats | +/++/+++* | ++/+++* | Unexplored | Unexplored |

+/++/+++: The proportion of projecting spiny inverted neurons out of various projection neurons at infragranular layers falls between 10 and 20%, 20 and 40% and is above 40%, respectively.

The incidence of projecting spiny inverted neurons out of various projection neurons at infragranular layers depends on the area and the specific projection (i.e. backward, forward, lateral, contralateral, occipital, temporal, discrete, diffuse).

Ipsilateral cortico-cortical projection

In rabbit neocortical infragranular layers, spiny inverted neurons make up around 25% of neurons which project ipsilaterally to other cortical areas. However, this percentage varies between the feedback and feedforward streams of visual projection. It differs also between the visual and auditory cortices. Thus, injections into the primary visual cortex revealed that spiny inverted neurons account for 26% of all retrogradely labelled neurons in infragranular layers of the ipsilateral secondary visual cortex. When injections were delivered into the secondary visual cortex, only 7.5% of the retrogradely labelled cells (i.e. which provide feedforward information) in area 17 infragranular layers were found to be spiny inverted neurons. Following injections into the auditory secondary cortex, we found 42% of retrogradely labelled neurons in infragranular layers of the primary auditory cortex to be spiny inverted neurons. The incidence of spiny inverted neurons which contribute from infragranular layers to ‘lateral’ ipsilateral cortico-cortical projections (i.e. among secondary areas) was 31%. All these percentages were estimated taking into account all infragranular neurons within clear-cut columns of retrograde labelling following tracer injections that extended along the radial dimension of the cortex without entering the white matter (Fig. 7a,c) (Bueno-Lopez et al. 1991; Reblet et al. 1992). We have not studied the projection from secondary to primary auditory cortex.

Moreover, spiny inverted neurons make up the majority (82%) of cells that form a horizontally widespread band of cells which are located at the border between layers V and VI of the visual cortex and project to the ipsilateral primary visual cortex in rabbits (Fig. 7c,d). This band of retrogradely labelled cells extends from the site of injection of WGA-HRP across the primary visual cortex to enter into the secondary visual cortex. This band is particularly striking in brains after multiple tracer injections (Reblet et al. 1992). These findings have shown that there is a highly convergent projection from layer V/VI border cells distributed throughout visual cortex to discrete points of the primary visual cortex. Spiny inverted neurons are the principal source of this type of projection. This widespread projection is distinct from the backward cortico-cortical projection from secondary to primary visual cortex which originates in discrete columnar patches of cells (referred to above). No similar widespread projection from the primary to the secondary visual cortex has been found.

In cats (Einstein & Fitzpatrick, 1991; Einstein, 1996) and macaque monkeys (De Lima et al. 1990), spiny inverted neurons are callosal and ipsilateral cortico-cortical projection cells. We injected WGA-HRP into cat area 17 and CTb into cat posterolateral lateral suprasylvian sulcus (area PLLS) (C.R. and J.L.B.-L., unpublished data). We also injected rhodamine latex beads into cat area 17; we subsequently filled the rhodamine retrogradely labelled cells with Lucifer Yellow by means of intracellular injections in semifixed slices (Fig. 4) (Reblet et al. 1993 and unpublished data). Following these injections, many spiny inverted neurons were identified as a source for the backward projection from the infragranular layers of areas PLLS, posteromedial lateral suprasylvian sulcus (PMLS), 21a, 19 and 18 to area 17. They also furnished in abundance long-range intrinsic projections within area 17. The incidence of spiny inverted neurons as projection cells to area 17 was area-specific in areas PLLS, PMLS, 21a, 19, 18 and 17. Of the projection cells that lay in infragranular layers of each of these areas, labelled spiny inverted neurons comprised as much as 72% in areas 19 and 17. As a source for the lateral cortico-cortical projection to area PLLS, the incidence of spiny inverted neurons was smaller though still important. Thus, these cells constituted 23, 39 and 54% of the labelled cells that lay in the infragranular layers of areas PMLS, 20b and 20a, respectively. It is of interest to note that all these percentages would have been up to 39% higher (depending on areas) if we had included labelled horizontally orientated cells in these quantifications. Although labelled horizontally orientated cells were in general less numerous than labelled spiny inverted neurons, their number increased towards the bottom of the sulci (Fig. 7b). These results indicate that spiny inverted neurons play a distinct yet unknown role in the neuronal backward flow of activation from secondary visual areas to the primary visual area, both in cats and in rabbits. They are qualitatively important also in cortico-cortical lateral connections, i.e. between areas of comparable cortical hierarchy.

Contralateral cortico-cortical projection

Spiny inverted neurons sited in infragranular layers contribute to contralateral cortico-cortical projections in rabbits. WGA-HRP tracer injected into the medial division of the primary visual cortex (which is associated with peripheral monocular vision) labels callosum neurons, which are arranged in radial clear-cut columns encompassing layers II–V in heterotopic contralateral cortical sites of the primary and secondary visual cortex (Bueno-Lopez et al. 1991). The tracer also labels a horizontal band in layer V that stretches widely across the primary visual cortex into the secondary visual cortex. With injections into the lateral part of primary visual cortex (which is associated with the binocular vision of the vertical central meridian of the visual field) next to the secondary visual cortex, contralateral labelling appears only at the homotopic border between the primary and secondary contralateral visual cortex. Spiny inverted neurons made up, on average, one out of three in the columns and two out of three in the horizontal band of infragranular contralateral cells that were retrogradely labelled in these experiments.

In turn, tracer injected into the rabbit secondary auditory cortex labelled many infragranular neurons of the contralateral temporal cortex. According to our estimations, labelled spiny inverted neurons make up 20% of all these labelled infragranular neurons.

Cortico-claustral projection

Injections of WGA-HRP and BDA tracers into the rabbit dorsal claustrum retrogradely labelled spiny inverted neurons scattered throughout the cortex (Bueno-Lopez et al. 1991; Gutierrez-Ibarluzea et al. 1999). As observed in the visual, auditory, sensory motor and retrosplenial cortices, cortico-claustral neurons lie in layers V–VI. Spiny inverted neurons with axon projections to the claustrum appear mainly in layer VI, but also in layer V of these cortices. In the visual primary cortex they constitute more than 80% of various infragranular cells with axon projection to the claustrum. By contrast, in secondary visual and auditory cortices, spiny inverted neurons with axon projection to the claustrum make up 23% (secondary visual cortex) and 24% (secondary auditory cortex) of the cortico-claustral neurons. In the retrosplenial cingulate cortex, spiny inverted neurons constitute only 10% of the infragranular cortico-claustral cells.

Cortico-striatal projection

Injections of the WGA-HRP tracer into the rabbit caudate nucleus revealed that spiny inverted neurons constitute less than 20% of the projection neurons that lie in infragranular layers of the occipital and temporal neocortex (Bueno-Lopez et al. 1991).

Other corticofugal projections

Finally, spiny inverted neurons have not been found in significant numbers to be a source of cortico-fugal projections to non-telencephalic centres, such as the colliculi, the lateral and medial geniculate nuclei, or the pons, at least in rabbits, using WGA-HRP (Bueno-Lopez et al. 1991). In keeping with this finding, very few spiny inverted neurons with axon projection to the pons were seen in layer V of the cat suprasylvian sulcus (Albus et al. 1981). Spiny inverted neurons were not part of the morphologically and physiologically characterized layer VI corticofugal neurons with axon projection presumably to the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus in the mouse primary visual cortex (Brumberg et al. 2003).

Radial placement

The extent to which the spiny inverted neurons that provide the projections reviewed above may have bifurcated axons that reach two or more targets is currently unknown. However, it is probable that this occurs infrequently, on the basis of the disparity of radial placements of the subpopulations of spiny inverted neurons with axon projection to a specific target. As mentioned above, the majority of spiny inverted neurons lie within the infragranular layers of the cerebral cortex (Globus & Scheibel, 1967; Parnavelas et al. 1977; Miller, 1988; Bueno-Lopez et al. 1991; Reblet et al. 1992; Gutierrez-Ibarluzea et al. 1999; Prieto & Winer, 1999; Qi et al. 1999). Some spiny inverted neurons are located throughout the remaining layers, with the exception of layer I (Miller, 1988; Bueno-Lopez et al. 1991; Gabbott & Bacon, 1995; Casanovas-Aguilar et al. 1998). Inverted neurons participating in the ipsilateral cortico-cortical projection are usually located at the border of layers V/VI in the rabbit, whereas those sending axons to the contralateral cortex lie in layer V, but usually away from the V/VI border in the same animal (Bueno-Lopez et al. 1991). The highest percentages of cortico-cortical spiny inverted neurons were consistently associated with layers VI and then V of any cat cortical area with projection neurons to area 17. The percentages estimated for layer II–III were lower than those for layer IV. Spiny inverted neurons providing for the cortico-claustral projection lie mainly in layer VI in the auditory and visual cortices of the rabbit (Bueno-Lopez et al. 1991; Gutierrez-Ibarluzea et al. 1999). In addition, spiny inverted neurons with axon projections to the nucleus caudatus from the temporal and occipital cortex of the rabbit lie in layer VI, but many more lie in layer V (Bueno-Lopez et al. 1991).

In general, we found that spiny inverted neurons (when defined as a group in terms of a specific axon projection) were located below the typically orientated cells whose axons were aimed at the same target (Bueno-Lopez et al. 1991; Reblet et al. 1992). This mirror symmetry in their radial location may have as a consequence that (1) typical pyramidal neurons and spiny inverted neurons can together efficiently collect information from all the pertinent afferent axons to a given cortical stratum or (2) each of these subgroups of projection cells can separately receive its synaptic contacts from distinct collections of afferent axons. The latter possibility, in particular, deserves to be verified given its important functional implications.

Concluding remarks

Spiny inverted neurons are infragranular cells which largely furnish axons to ipsilateral and contralateral cortical areas and the claustrum. What makes these cells particularly interesting is their odd dendrite polarization and narrow radial placement in the cortex, which probably gives rise to a unique integration of synaptic inputs, which is peculiar to these cells. Thus, two distinctly qualified axonal outputs may be contained within a specific projection (as defined by the target centre) which begins at the infragranular layers of a cortical area: one delivered by the typical pyramidal neurons, the other by the spiny inverted neurons. Furthermore, the preliminary evidence we have found for differences in synaptic input onto the axon initial segment of subsets of typical pyramidal neurons and spiny inverted neurons will probably give rise to differences in at least two important cell-electrophysiology mechanisms. First, such differences would cause distinct backward modulations of the membrane potential of the parent cells (Howard et al. 2005). Secondly, the initiation of the axon potential would be eventually controlled by collections of axon input that are particular, at least numerically, for each cell subset (Karayannis et al. 2007). More work on the specific innervation of typical pyramidal neurons and spiny inverted neurons of the mammal cerebral cortex is clearly warranted.

Acknowledgments

This work was part-funded by grants MEC-BSA2001-1179 and 9/UPV00212.327-15837/2004 of the Spanish Government and the Basque Country University, respectively.

References

- Albus K, Doñate-Oliver F, Sanides D, Fries W. The distribution of pontine projection cells in visual and association cortex of the cat: an experimental study with horseradish peroxidase. J Comp Neurol. 1981;201:175–189. doi: 10.1002/cne.902010204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimatsu Y, Nihonmatsu I, Hirata K, Takiguchi-Hayashi K. Cogeneration of neurons with a unique molecular phenotype in layers V and VI of widespread lateral neocortical areas in the rat. J Neurosci. 1994;14:2020–2031. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-04-02020.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimatsu Y, Kojima M, Ishida M. Area- and lamina-specific organization of a neuronal subpopulation defined by expression of latexin in the rat cerebral cortex. Neuroscience. 1999;88:93–105. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belichenko PV, Dahlstrom A, Von Essen C, Lindstrom S, Nordborg C, Sourander P. Atypical pyramidal cells in epileptic human cortex: CLSM and 3D reconstructions. Neuroreport. 1992;3:765–768. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199209000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Santiago RI. University of the Basque Country; Desarrollo de las células invertidas corticales en el conejo. Doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Bordalier C, Robain O, Rethore MO, Dulac O, Dhellemes C. Inverted neurons in Agyria. A Golgi study of a case with abnormal chromosome. Hum. Genet. 1986:73. doi: 10.1007/BF00279105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumberg JC, Hazmei-Sichani F, Yuste R. Morphological and physiological characterization of layer VI corticofugal neurons of mouse primary visual cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:2854–2867. doi: 10.1152/jn.01051.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueno-Lopez JL, Reblet C, Lopez-Medina A, et al. Targets and laminar distribution of projection neurons with inverted morphology in rabbit cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 1991;3:415–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1991.tb00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cajal-Agüeras SR, Lopez-Mascaraque L, Ramo C, Contamina-Gonzalvo P, De Carlos JA. Layer I and VI of the visual cortex in the rabbit. A correlated Golgi and immunocytochemical study of somatostatin and vasoactive intestinal peptide containing neurons. J Hirnforsch. 1989;2:163–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanovas-Aguilar C, Reblet C, Perez-Clausell J, Bueno-Lopez JL. Zinc-rich afferents to the rat neocortex: projections to the visual cortex traced with intracerebral selenite injections. J Chem Neuroanat. 1998;72:97–109. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(98)00035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colonnier M. Synaptic pattern on different cell types in the different lamina of the cat visual cortex. Brain Res. 1968;9:268–287. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(68)90234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lima AN, Voigt T, Morrison JH. Morphology of the cells within the inferior temporal gyrus that project to the prefrontal cortex in the macaque monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1990;296:159–172. doi: 10.1002/cne.902960110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFelipe J, Jones EG. The functional histology of the cerebral cortex and the continuing relevance of Cajal's observations. In: DeFelipe J, Jones EG, editors. Cajal on the cerebral cortex: An Annotated Translation on the complete writings (History of Neuroscience; Nº 1) New York: Oxford University Press; 1988. pp. 557–621. (1988) [Google Scholar]

- DeFelipe J, Fariñas I. The pyramidal neuron of the cerebral cortex: morphological and chemical characteristics of the synaptic inputs. Prog Neurobiol. 1992;39:563–607. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(92)90015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehay C, Kennedy H. Cell-cycle control and cortical development. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:438–450. doi: 10.1038/nrn2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einstein G, Fitzpatrick D. Distribution and morphology of area 17 neurons that project to the cat's extrastriate cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1991;303:132–149. doi: 10.1002/cne.903030112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einstein G. Reciprocal connections of cat extrastriate cortex. I. Distribution and morphology of neurons projecting from posterior medial lateral suprasylvian sulcus to area 17. J Comp Neurol. 1996;376:518–529. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19961223)376:4<518::AID-CNE2>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabri M, Manzoni T. Glutamic acid decarboxylase immunoreactivity in callosal projecting neurons of cat and rat somatic sensory areas. Neuroscience. 2004;123:557–566. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer I, Fabregues I, Condom E. A Golgi study of the sixth layer of the cerebral cortex. I. The lissencephalic brain of Rodentia, Lagomorpha, insectivore and Chiroptera. J Anat. 1986a;145:217–234. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer I, Fabregues I, Condom E. A Golgi study of the sixth layer of the cerebral cortex. II. The gyrencephalic brain of Carnivora, Atiodactyla and Primates. J Anat. 1986b;146:87–104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda T, Kosaka T. Ultrastructural study of gap junctions between dendrites of Parvalbumin-containing GABAergic neurons in various neocortical areas of the adult rat. Neuroscience. 2003;120:5–50. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbott PLA, Bacon SJ. Co-localization of NADPH diaphorase activity and GABA immunoreactivity in local circuit neurones in the medial prefrontal cortex of the rat. Brain Res. 1995;699:321–328. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Globus A, Scheibel AB. Pattern and field in cortical structure: The rabbit. J Comp Neurol. 1967;131:155–172. doi: 10.1002/cne.901310207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golgi C. Sulla Sostanza grigia del cervello. Opera Omnia. 1873;1:91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Urquijo SM, Reblet C, Bueno-Lopez JL, Gutierrez-Ibarluzea I. GABAergic neurons in the rabbit visual cortex: percentage, layer distribution and cortical projections. Brain Res. 2000;862:171–179. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02114-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonchar YA, Jonson PB, Weinberg RJ. GABA-immunopositive neurons in rat neocortex with contralateral projections to SI. Brain Res. 1995;697:27–34. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00746-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Ibarluzea I, Acera-Osa A, Mendizabal-Zubiaga JL, et al. Morphology and laminar distribution of cortico-claustral neurons in different areas of the rabbit cerebral cortex. Eur J Anat. 1999;3:101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Hallman LE, Shofield BR, Lin CS. Dendritic morphology and axon collaterals of corticotectal, corticopontine and callosal neurons in layer V of primary visual cortex of hooded rat. J Comp Neurol. 1988;272:149–160. doi: 10.1002/cne.902720111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard A, Tamas G, Soltesz I. Lighting the chandelier: new vistas for axo-axonic cells. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:310–316. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hübener M, Bolz J. Morphology of identified projection neurons in layer V of rat visual cortex. Neurosci Lett. 1988;94:76–81. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90273-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hübener M, Schwarz C, Bolz J. Morphological types of projection neurons in layer V of cat visual cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1990;301:655–674. doi: 10.1002/cne.903010412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Mathers PH, Szabo G, Katarova Z, Agmon A. Vertical bias in dendritic trees of non-pyramidal neocortical neurons expressing GAD67–GFP in vitro. Cereb Cortex. 2001;11:666–678. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.7.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG, Powell TPS. Electron microscopy of the somatic sensory cortex of the cat. I. Cell types and synaptic organization. Phil Trans R Soc Lond. 1970;B257:1–11. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1970.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karayannis T, Huerta-Ocampo I, Capogna M. GABAergic and pyramidal neurons of deep cortical layers directly receive and differently integrate callosal input. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:1213–1226. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LC. Local circuitry of identified projection neurons in cat visual cortex brain slices. J Neurosci. 1987;7:1223–1249. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-04-01223.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrieu P, Goffinet A. Inverted pyramidal neurons and their axons in the neocortex of the reeler mutant mice. Cell Tissue Res. 1981;218:293–301. doi: 10.1007/BF00210345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund RD. Development and Plasticity of the Brain. New York: Oxford University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Marin-Padilla M. Prenatal ontogenetic history of the principal neurons of the neocortex of the cat (felix domestica). A Golgi study. II. Developmental differences and the significance. Z Anat Entwgesch. 1972;136:125–142. doi: 10.1007/BF00519174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara JA, Chase R, Thejomayen M. Comparative morphology of three types of projection-identified pyramidal neurons in the superficial layers of cat visual cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1996;366:93–108. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960226)366:1<93::AID-CNE7>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute C, Streit P. Monoclonal antibodies demonstrating GABA like immunoreactivity. Histochemistry. 1986;86:147–157. doi: 10.1007/BF00493380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald CT, Burkhalter A. Organization of long-range inhibitory connections within rat visual cortex. J Neurosci. 1993;13:768–781. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00768.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendizabal-Zubiaga JL. University of The Basque Country; Sinapsis axo-axónicas y otros parámetros de los segmentos iniciales axónicos de células piramidales clásicas e invertidas de las capas infragranulares de la corteza cerebral de la rata. Doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Miller MV. Maturation of rat visual cortex. IV. The generation, migration and connectivity of atypically oriented pyramidal neurons. J Comp Neurol. 1988;274:387–405. doi: 10.1002/cne.902740308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar Z, Cheung AFP. Towards the classification of subpopulations of layer V pyramidal projection neurons. Neurosci Res. 2006;55:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molyneaux BJ, Arlotta P, Menezes JRL, Macklis JD. Neuronal subtype specification in the cerebral cortex. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:427–437. doi: 10.1038/nrn2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary JL, Bishop GH. The optically excitable cortex of the rabbit. J Comp Neurol. 1938;68:423–478. [Google Scholar]

- Parnavelas JG, Lieberman AR, Webster KE. Organization of neurons in the visual cortex, area 17, of the rat. J Anat. 1977;124:305–322. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A. Stellate cells of the rat parietal cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1971;141:345–374. doi: 10.1002/cne.901410306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Kara DA. The neuronal composition of area 17 of rat visual cortex I. The pyramidal cells. J Comp Neurol. 1985a;234:218–241. doi: 10.1002/cne.902340208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Kara DA. The neuronal composition of area 17 of rat visual cortex II. The non-pyramidal cells. J Comp Neurol. 1985b;234:242–263. doi: 10.1002/cne.902340209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto-Lord MC, Caviness VS. Determinants of cell shape and orientation: a comparative Golgi analysis of cell axon interrelationships in the developing neocortex of normal and reeler mice. J Comp Neurol. 1979;187:49–70. doi: 10.1002/cne.901870104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto JJ, Winer JA. Layer VI in cat primary auditory cortex: Golgi study and sublaminar origins of projection neurons. J Comp Neurol. 1999;404:332–358. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990215)404:3<332::aid-cne5>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi HX, Jain N, Preuss TM, Kass JH. Inverted pyramidal neurons in chimpanzee sensorimotor cortex are revealed by immunostaining with monoclonal antibody SMI-32. Somatosens Mot Res. 1999;16:49–56. doi: 10.1080/08990229970645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramón y Cajal S. On the structure of the cerebral cortex of certain mammals. (La Cellule 7: 125–176) In: DeFelipe J, Jones EG, editors. Cajal on the cerebral cortex: An Annotated Translation on the complete writings (History of Neuroscience; Nº 1) New York: Oxford University Press; 1891. pp. 23–54. (1988) [Google Scholar]

- Ramón y Cajal S. Histologie du Systeme Nerveux de l’Homme et des Vertebres. Paris: Maloine; 1911. [Google Scholar]

- Reblet C, Lopez-Medina A, Gomez-Urquijo SM, Bueno-Lopez JL. Widespread horizontal connections arising from layer 5/6 border inverted cells in rabbit visual cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 1992;4:221–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1992.tb00870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reblet C, Perez-Samartin A, Caballero A, Marín I, Bueno-Lopez JL. Identified inverted cells in the cortico-cortical projections from extrastriate to striate visual cortex of cats. Eur J Neurosci. 1993;6(Suppl):13. [Google Scholar]

- Reblet C, Blanco-Santiago I, Mendizabal-Zubiaga JL, Gutierrez-Ibarluzea I, Bueno-Lopez JL. Development of inverted cells in infragranular layers of the rabbit visual cortex. Int J Dev Biol. 1996;1(Suppl):145–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheibel ME, Scheibel AB. The dendritic structure of the human Betz cell. In: Brazier MAB, Petsche H, editors. Architectonics of the Cerebral Cortex (IBRO) Monographic Series. Vol. 3. New York: Raven Press; 1978. pp. 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Somogyi P. A specific ‘axo-axonal’ interneuron in the visual cortex of the rat. Brain Res. 1977;136:345–350. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90808-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somogyi P, Freund TF, Cowey A. The axo-axonic interneuron in the cerebral cortex of the rat, cat and monkey. Neuroscience. 1982;7:2577–2607. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(82)90086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada T, Becker LE, Chan F. Aberrant dendritic development in the human agyric cortex: a quantitative and qualitative Golgi study of two cases. Clin Neuropathol. 1988;7:111–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tömböl T. Layer VI cells. In: Peters A, Jones EG, editors. Cerebral Cortex. Vol. 1. New York: Plenum Press; 1984. pp. 479–520. [Google Scholar]

- Tomioka R, Okamoto K, Furuta T, et al. Demonstration of long-range GABAergic connections distributed throughout the mouse neocortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:1587–1600. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03989.x. Erratum: Eur J Neurosci 21, 2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Brederode JF, Helliesen MK, Hendrickson AE. Distribution of the calcium-binding proteins parvalbumin and calbindin-D28k in the sensorimotor cortex of the rat. Neuroscience. 1991;44:157–171. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90258-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Brederode JF, Snyder GL. A comparison of the electrophysiological properties of morphologically identified cells in layers Vb and VI of the rat neocortex. Neuroscience. 1992;50:315–337. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Loos H. The ‘improperly’ oriented pyramidal cell in the cerebral cortex and its possible bearing on problems of neuronal growth and cell orientation. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1965;117:228–250. [Google Scholar]

- Williams RS, Ferrante RJ, Caviness VS. Neocortical organization in human cerebral malformation: a Golgi study. Soc Neurosci Abstract. 1975;1:776. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Samejima A, Oka H. Morphological features of layer V pyramidal neurons in the cat parietal cortex: an intracellular HRP study. J Comp Neurol. 1987;265:380–390. doi: 10.1002/cne.902650307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong-Wei Z, Deschenes M. Intracortical axonal projections of lamina VI cells of the primary somatosensory cortex in the rat: a single-cell labeling study. J Neurosci. 1997;17:6365–6379. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-16-06365.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]