Abstract

Although the cardiac coronary system in mice has been the studied in detail by many research laboratories, knowledge of the cardiac veins remains poor. This is because of the difficulty in marking the venous system with a technique that would allow visualization of these large vessels with thin walls. Here we present the visualization of the coronary venous system by perfusion of latex dye through the right caudal vein. Latex injected intravenously does not penetrate into the capillary system. Murine cardiac veins consist of several principal branches (with large diameters), the distal parts of which are located in the subepicardium. We have described the major branches of the left atrial veins, the vein of the left ventricle, the caudal veins, the vein of the right ventricle and the conal veins forming the conal venous circle or the prepulmonary conal venous arch running around the conus of the right ventricle. The venous system of the heart drains the blood to the coronary sinus (the left cranial caval vein) to the right atrium or to the right cranial caval vein. Systemic veins such as the left cranial caval, the right cranial caval and the caudal vein open to the right atrium. Knowledge of cardiac vein location may help to elucidate abnormal vein patterns in certain genetic malformations.

Keywords: cardiac veins, coronary sinus, heart, left cranial caval vein, mouse

Introduction

Cardiac veins in normal mice have not previously been described in the literature. Much work has been done on the coronary artery pattern in species with an intramyocardial course of coronary arteries (Halpern, 1957; Ahmed et al. 1978; Vincentini et al. 1991) and on the embryonic development of the coronary system, including its venous part (Dbalý & Rychter, 1966a, b; Dbalý et al. 1968; Rychter & Ošt’ádal, 1971; Bogers et al. 1988, 1989; Vrancken Peeters et al. 1997a, b). Information about the distribution of major veins of the mouse heart is lacking; and because mice are often used as transgenic animals, it is important to understant the normal structure of the venous system. Furthermore, our current terminology of the cardiac venous system in rodents is inadequate. The relationship between normal vessel pattern and its pathology in some genetic malformations has not been described in mice. However, some abnormal veins have been described in various malformations of the human heart (Uemura et al. 1995, 1996). In mice, the cardiac veins run on the surface of the heart within the subepicardium, draining the myocardium of the left and the right ventricles as well as the left atrium. They empty to the right atrium or to the coronary sinus; the latter is formed from the proximal part of the left cranial caval vein (LCCV) (Webb et al. 1996, 1998). Here we describe the normal pattern of cardiac veins in adult mice; this could serve as a reference point for comparing of cardiac veins in geneticaly modified mice (transgenic animals).

Materials and methods

Animals

The sample studied consisted of 46 mice (22 males and 24 females) of outbred MIZZ colonies (Mus musculus L.), not corresponding to any fixed strain (bred by the University of Warsaw Animal Care Unit). Animals were kept in cages in the animal care room with water and food available ad libitum. The animals were anaesthetized intraperitoneally with chloral hydrate (100 mg kg−1 b.w.). The heart and the right caudal vein were exposed by median thoracotomy and the right caudal vein was rinsed with physiological saline containing 1% papaverin, and subsequently white or coloured latex dye was injected via the vein. The animal was then immersed in 4% formalin for 3 weeks. After this time the heart and major vessels were removed, cleaned of fat and connective tissue, and the cardiac vein courses were analysed under a stereomicroscope. In order to visualize the atrial venous system it was necessary to dissect and cut out the pulmonary trunk and the ascending aorta. Dissection was performed with a standard set of microsurgical instruments. Photographs were taken digitally and stored on a personal computer. The 2nd Local Ethics Committee for Animal Research in Warsaw approved the project.

Thesis

We propose a terminology related to the venous system of the mouse heart. This terminology represents a modification of the veterinary and the human anatomical terminology (nomenclature) based on our anatomical investigations. It is presented below and is used consistently throughout:

Vena cordis sinistra – the left cardiac vein (LCV)

Vena caudalis major – the major caudal vein (MCV)

Venae caudales minores – minor caudal veins (MiCV)

Vena cordis dextra – the right cardiac vein (RCV)

Venae cordis craniales – cranial cardiac veins (CCV)

Vena coni arteriosi dx – the right conal vein (RCoV)

Vena coni arteriosi sin. – the left conal vein (LCoV)

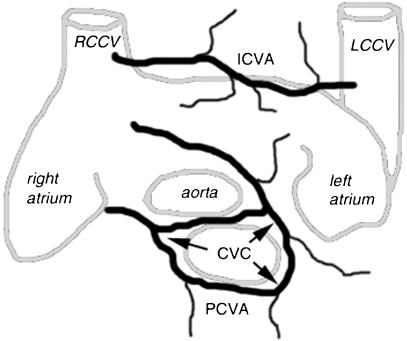

Arcus venosus coni arteriosi prepulmonalis – the prepulmonary conal venous arch (PCVA) (Fig. 1)

Circulus venosus coni arteriosi – the conal venous circle (CVC)

Venae atrii sinistri – left atrial veins (LAV)

Arcus venosus intercavalis – the intercaval venous arch (ICVA) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the conal venous circle (CVC) and intercaval venous arch (ICVA). The CVC is located around the pulmonary trunk and partially encircles the aorta.

Given the lack of a precise description of the mouse heart atria in the literature, we have also introduced several terms that are necessary for topographical description.

Atria

Pulmonary surface – the outer surface of the atrium facing the lungs.

Surface of the coronary sinus – the outer surface of the atrium facing the coronary sinus.

Mediastinal surface – facing the upper mediastinum

Conal surface facing the infundibulum of the right ventricle, the pulmonary trunk and the ascending aorta.

Description of ventricles in relation to Nomina Anatomica Veterinaria 2005

Sternal surface – facies sternalis – auricular surface

Anterior interventricular groove – paraconal interventricular groove – sulcus interventricularis paraconalis

Diaphragmatic surface – facies diaphragmatica – atrial surface

Posterior interventricular groove – subsinusoidal interventricular groove – sulcus interventricularis subsinusoidalis.

Main body

All veins described below were located superficially under the epicardium.

There were several patterns of major cardiac veins draining the surface of the left artium and both ventricles.

Cardiac veins return blood to the coronary sinus, directly to the right atrium or to the right cranial caval vein.

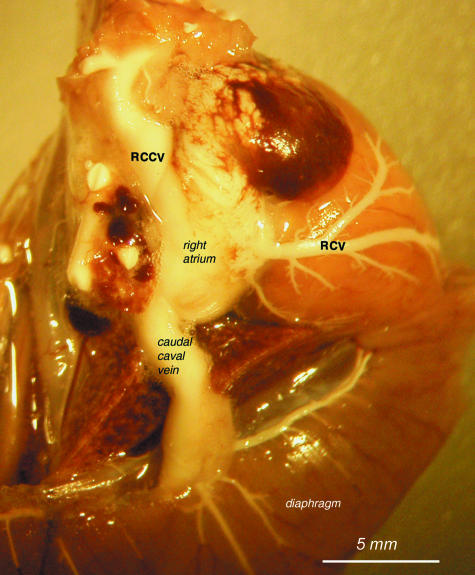

In rodents such as mice the coronary sinus is the terminal segment of the left cranial caval vein (LCCV), which receives blood from the cardiac and from systemic circulation. The left cranial caval vein runs obliquely on the coronary sinus surface of the left atrium in the coronary sulcus and opens to the right atrium. The left cranial caval vein opens to the right atrium below the mouth of the right cranial caval (RCCV) and the caudal caval veins. All three systemic veins empty to the right atrium.

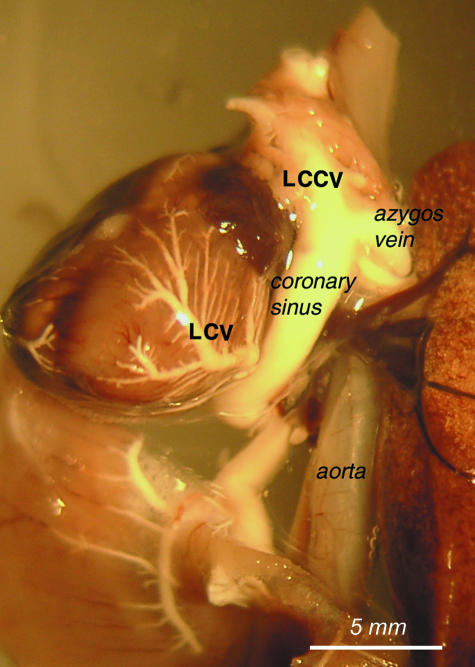

As the borders of the coronary sinus have not been defined before, we decided to classify the coronary sinus as the distal segment of the left cranial caval vein, i.e. between the mouth of the azygos vein and the opening of left cranial caval vein to the right atrium (Figs 2–4).

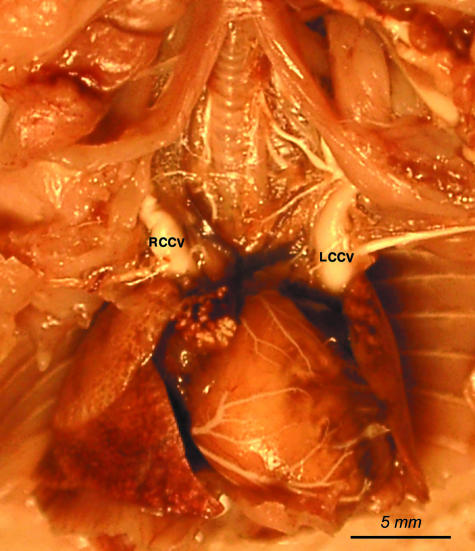

Fig. 2.

View of the heart in situ with both cranial caval veins: the left cranial caval vein (LCCV) and the right cranial caval vein (RCCV) are injected with white latex.

Fig. 4.

View of the course of the left cranial caval vein (LCV) and azygos vein to demonstrate borders of the coronary sinus. The left cardiac vein (LCV) opening to the coronary sinus is also visible.

Fig. 3.

View of the right atrium with the right cranial caval vein (RCCV) and caudal caval vein. The right cardiac vein (RCV) is also visible with its major branch running on the surface of the right ventricle.

Left atrial veins (LAV)

The first tributaries of the coronary sinus were the veins of the left atrium. They exhibit various patterns of draining and various relationships with the conal veins. Usually they merge with the conal veins. Left atrial veins were visualized in 18/24 females and in 20/22 males. Only in one female and two males did veins from the conal surface drain exclusively to the right atrium. In other specimens they opened to the coronary sinus.

The left atrial vein consisted of a single vessel in 11 females and 15 males, and a double vessel in eight females and five males. In one male there was a triple left atrial vein. The left atrial vein drained the pulmonary, or the mediastinal and the pulmonary, or the conal surface of the atrium. The detailed drainage areas of the left atrial vein are presented in Table 1 (see also Fig. 5).

Table 1.

Distribution of LAV

| Surfaces | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of vessels | Mediastinal | Pulmonary | Med/pulmon | Conal |

| Female | ||||

| One | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| Two | 1 | 3 | 4 | |

| Male | ||||

| One | 9 | 1 | 5 | |

| Two | 1 | 4 | ||

| Three | 1 | |||

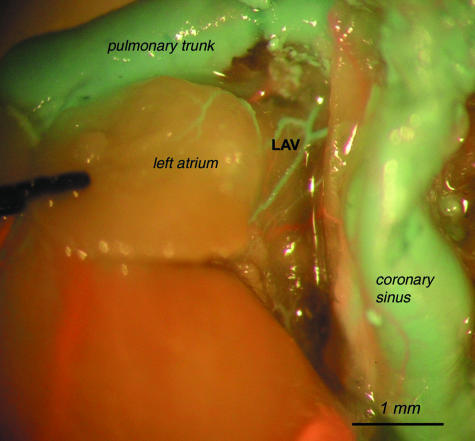

Fig. 5.

View of the left atrial vein (LAV) on the pulmonary and mediastinal surface of the left atrium.

The left atrial veins frequently constitute anastomoses with a mediastinal venous system. The anastomoses were observed in seven females and eight males. When an anastomosis between the left atrial vein and the right atrium or between the left atrial vein and the left conal vein is observed, it is referred to as the intercaval venous arch (ICVA). It was found in 11 females and nine males (Fig. 6).

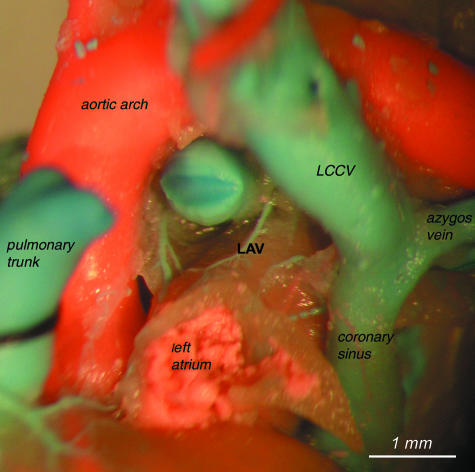

Fig. 6.

Drainage of the mediastinal surface of the left atrium by the left atrial vein (LAV) tributaries.

Left cardiac vein (LCV)

The largest tributary of the coronary sinus was the left cardiac vein, which partially drained the sternal areas and the diaphragmatic surface of the left ventricle. In most cases it collected blood from the two major branches, which converged into a main vessel running on the diaphragmatic surface of the left ventricle and subsequently led to the coronary sinus on the level of the left atrium.

The proximal parts of these branches received blood from many tributaries from both surfaces of the heart and from the apex. The left cardiac vein opened to the coronary sinus with a solitary mouth (20 specimens) or it confluenced at the opening with the major caudal vein of the heart (22 specimens) or via a common lateral anastomosis between the mouth of the left cardiac vein and the mouth of the major caudal vein (eight cases).

In some cases it opened to the coronary sinus via an anastomosis between the mouth of the major caudal vein and the minor caudal veins (two cases).

The left cardiac vein drained the diaphragmatic surface of the left ventricle, except in 16 cases in which the caudal veins were located within this area of drainage.

A detailed analysis of left cardiac vein branch distribution was performed in 37 cases; however, owing to a defect of distal latex injection this was impossible in the remaining cases. Table 2 gives the location of the main vessel trunk and branching system of the left cardiac vein (Fig. 7).

Table 2.

Branching system of the LCV

| Two branches | One branch – auricular | One branch – from the apex | Three branches | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 9 | 5 | 4 | 18 | |

| Female | 13 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 19 |

| Total | 22 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 37 |

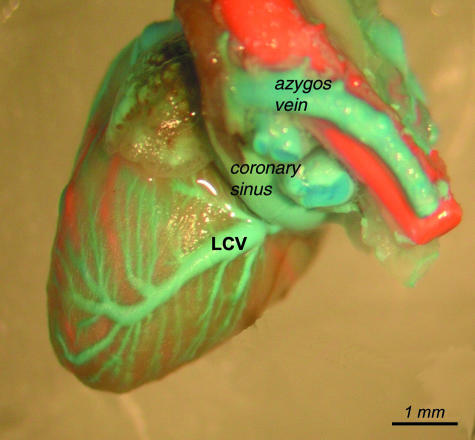

Fig. 7.

General view of the left cardiac vein (LCV).

In some cases when the conal veins were well developed, they drained the sternal surface of the left ventricle instead of the left cardiac vein branches.

Caudal veins

The major caudal vein (MCV) of the heart collects blood from the heart's diaphragmatic surface, mostly from the posterior interventricular groove. Minor caudal veins that drain the diaphragmatic surface of both ventricles develop in some cases. A latex-injected major caudal vein was observed in 41 hearts. In five cases there was a failed filling. In 43 hearts, however, it was possible to access the ostia. The major caudal vein originated from the diaphragmatic surface of the heart (Fig. 8), on various levels (Table 3).

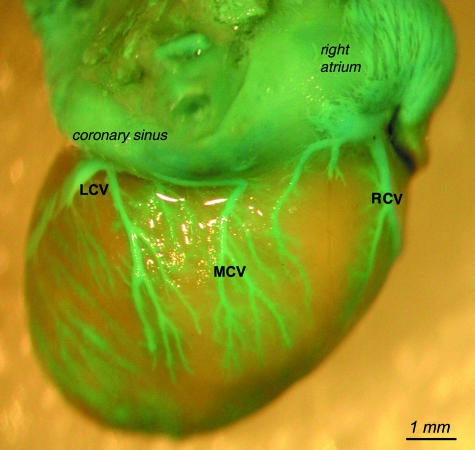

Fig. 8.

The major caudal cardiac vein (MCV) with its tributaries on the diaphragmatic surface of the heart. This heart surface is also drained by the right cardiac vein (RCV) tributary and partially by the left cardiac vein (LCV).

Table 3.

Origins of MCV and MiCV

| Upper half | Lower half | Apex | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 6 | 15 | 1 | 22 |

| Male | 4 | 12 | 3 | 19 |

| Total | 10 | 27 | 4 | 41 |

The major caudal vein opened to the coronary sinus as a single mouth, or together with the left cardiac vein, or with minor caudal veins as detailed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Openings of MCV to the coronary sinus

| Single mouth | With LCV | With LCV & MiCV | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 11 | 11 | 1 | 23 |

| Male | 10 | 9 | 1 | 20 |

| Total | 21 | 20 | 2 | 43 |

Minor caudal veins were observed in 45 cases. In one case the vessels did not fill with latex. In 20 cases there was one minor caudal vein, in 12 cases two, in six three, and in seven cases there were no minor caudal veins. Most frequently these veins opened to the coronary sinus or to the right atrium also by a common mouth with the right cardiac vein. In 11 cases (seven females, four males) a more complicated system of opening was observed. A venous arch parallel to the coronary sinus collected several caudal veins and could include ostia of the left cardiac vein and the right cardiac vein (Fig. 9).

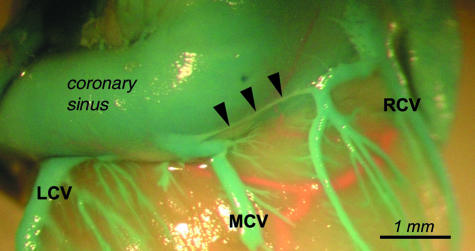

Fig. 9.

A channel (marked with arrowheads) connecting mouths of the major caudal vein (MCV) and the right cardiac vein (RCV) tributary.

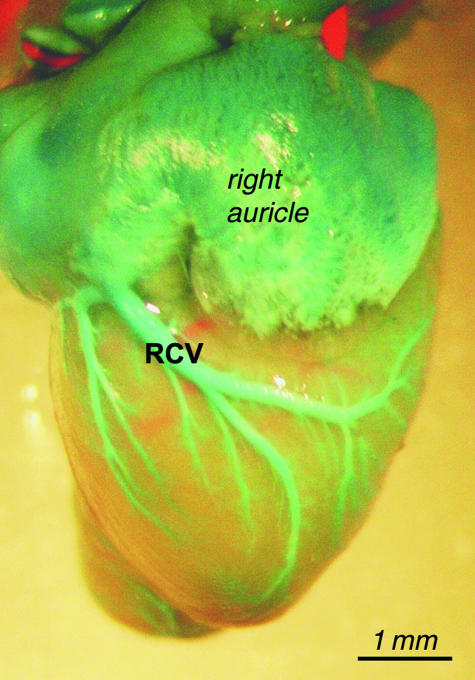

Right cardiac vein (RCV)

The right cardiac vein drains blood from the right ventricle. The most frequently observed pattern of the right cardiac vein consisted of two main branches (14 females, 15 males). One originated from the region adjacent to the heart apex. The second drained the sternal surface of the right ventricle. The branches merged into one trunk, which opened to the right atrium on the border between auricular and sinusoidal parts of the atrium. In 15 cases (nine females, six males) a single trunk of the right cardiac vein was observed, which originated close to the heart apex. In an additional two cases (one female, one male) a single trunk was observed collecting blood from the sternal surface of the right ventricle. The right cardiac vein opened to the right atrium, as a single vessel or more usually with minor caudal veins or the right conal vein (Table 5, Fig. 10).

Table 5.

Openings of RCV to the right atrium

| Single mouth | With MiCV | With RcoV | With MiCV & RCoV | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 11 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 24 |

| Male | 9 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 22 |

| Total | 20 | 16 | 5 | 5 | 46 |

Fig. 10.

General view of the right cardiac vein (RCV) with opening to the right atrium.

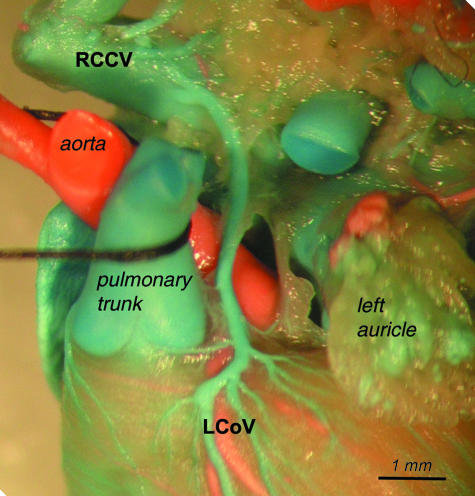

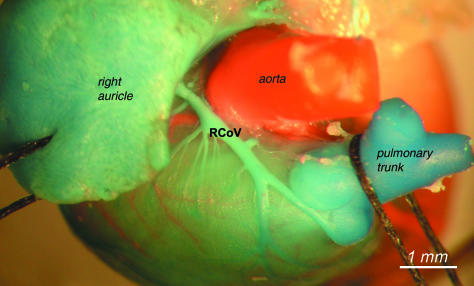

Right and left conal veins (RCoV and LCoV)

The right conal vein and the left conal vein originated on the sternal surface of the heart. Generally, the right one ran on the right circumference of the pulmonary root, crossed the ascending aorta, then entered the coronary groove, and opened to the right atrium.

The left conal vein ran on the left circumference of the pulmonary root, then went on the conal surface of the atria, and opened to the right atrium or to the right cranial caval vein (RCCV). In some cases the left conal vein and the right conal vein ran as separate vessels on both sides of the infundibulum of the right ventricle (conus arteriosus).

In several cases the whole drainage of the infundibulum of the right ventricle was directed to the right conal vein. The left conal vein was absent. The right conal vein ran from the left side of the infundibulum of the right ventricle through the border between the infundibulum of the right ventricle and the pulmonary trunk to the right side of the infundibulum of the right ventricle and opened to the right atrium (below the right auricle).

In many cases there was an anastomosis between the right conal vein and the left conal vein on the anterior surface of the pulmonary root. This is referred to as the prepulmonary conal venous arch (PCVA). Another observed pattern was a conal venous circle (CVC) in which a vessel went anteriorily and around the conus of the right ventricle behind the pulmonary trunk and coalesced with the same vessel again on the right side of the infundibulum of the right ventricle. The distribution of these variations is presented in detail in Table 6 (see also Figs 11 and 12).

Table 6.

Patterns of conal veins

| Two separate conal veins | PCVA | CVC | Only RCoV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 2 | 12 | 4 | 4 |

| Female | 2 | 14 | 3 | 5 |

| Total | 4 | 26 | 7 | 9 |

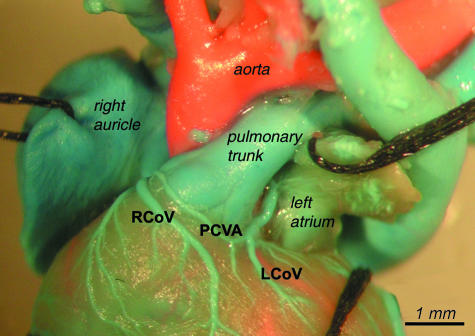

Fig. 11.

Course of the left conal vein (LCoV) opening to the right cranial caval vein (RCCV).

Fig. 12.

Course of the right conal vein (RCoV) in front of and at the root of the pulmonary trunk and under the right auricle.

In all cases, regardless of the pattern (prepulmonary conal venous arch, a conal venous circle, only the right conal vein, two separate conal veins), the openings of these vessels were in the right atrium closer or further from the mouth of the right cardiac vein (RCV). In some cases there was coalescence at the opening with the mouth of the right cardiac vein (seven females, three males). The draining branches of the right conal vein and the left conal vein were always located on the left, anterior and the right side of the infundibulum of the right ventricle (Figs 13 and 14a,b).

Fig. 13.

Conal venous arch consisting of the left conal vein (LCoV), the prepulmonary venous arch (PCVA) and the right conal vein (RCoV).

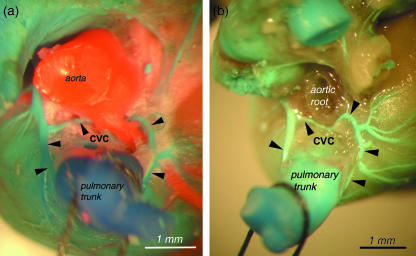

Fig. 14.

(a) Cranial view of the conal venous circle running under the left coronary artery marked with arrowheads; (b) cranial view of the conal venous circle (marked with arrowheads) running above the left coronary artery (compare with diagram in Fig. 1).

Cranial cardiac veins (CCV)

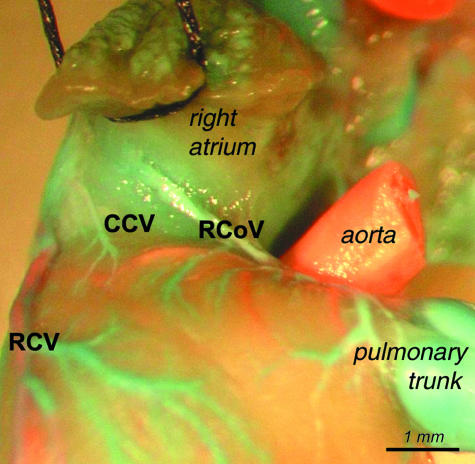

These vessels occasionally drained the sternal surface of the heart between the area of the right cardiac vein and the right conal vein and opened independently to the right atrium. Cranial cardiac veins were observed in four cases (three females, one male) (Figs 15 and 16).

Fig. 15.

View of the well-developed cranial cardiac vein (CCV) running between the right auricle and the right cardiac vein (RCV) and opening to the right atrium.

Fig. 16.

Small cranial cardiac vein (CCV).

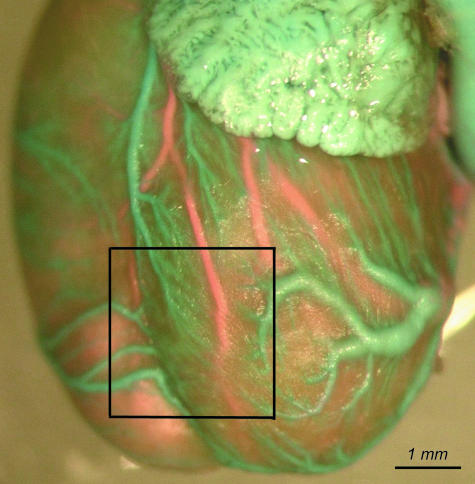

Anastomoses between the left cardiac vein and the right cardiac vein

Several anastomoses located superficially under the epicardium of the ventricles were observed. They connected areas of drainage of the left cardiac vein and the right cardiac vein on the sternal and diaphragmatic surfaces of the heart. The anstomoses were also observed in the apical region (Fig. 17).

Fig. 17.

Region of anastomoses between the left cardiac vein, the right cardiac vein and conal veins on the left ventricular wall and paraconal interventricular sulcus (in the rectangle).

Discussion

Here we have demonstrated that the cardiovenous system in mice comprises various patterns with regard to the location, area of drainage and communication between major vessels. To our knowledge this is the first detailed description of the venous system of the heart in mice. The only similar description of the rat heart venous system was by Halpern (1953).

There are two major areas of drainage by the cardiac veins: the left side and the right side of the heart. The left cardiac vein and the left conal vein belong to the left-side system, whereas the right cardiac vein and the right conal vein constitute the right-side system. The communication between the left and the right vessels is around the infundibulum of the right ventricle and via the subepicardial anastomoses.

The system of the left atrial vein constitutes a separate part and exhibits various draining patterns and different communications with the conal veins.

Organization of the left cardiac vein and the right cardiac vein is relatively constant. The greatest variability has been observed in the region of conal veins and the left atrial vein.

The major cardiac veins in mice do not lie parallel to the branches of the coronary arteries, the latter lying intramurally.

The results presented above are markedly different not just from those of the human anatomy but also from well-established descriptions of the heart venous system in larger animals, for example cattle, horses, pigs, dogs and cats (Sekeles, 1982). Thus, we cannot use the same terminology. Consequently, the terminology we have proposed is specific to the veins of the mouse heart.

The main difference between mice and the animals listed above is related to the presence of the left cranial caval vein. This vessel exists in rodents such as rats (Halpern, 1953) and also in rabbits (Grant & Regnier, 1926).

The left cranial caval vein is usually absent in humans. As a rare variation, called the left superior caval vein, it is present in 0.3% of healthy individuals and in 5% of patients with congenital heart malformations. In most cases it coexists with the superior caval vein in its normal right-sided position. As a single vessel it is observed in 10–20% cases (Cha & Khoury, 1972). The left cranial caval vein in humans does not collect blood from the heart.

This vessel is a remnant of the left sinus horn, which partially disappears during embryonic development. The remaining part of the left sinus horn differentiates into the coronary sinus and oblique vein of the left atrium (Marshal's vein) in humans. In pigs the oblique vein of the left atrium does not exist. In its place courses the left hemiazygos vein (Ratajczyk-Pakalska, 1974). The left cranial caval vein in mice is the vessel corresponding to the left sinus horn of embryonic development.

In dogs such a persistent left cranial caval vein is rarely observed. It was reported as a single vessel (Wyrost, 1968; Stefanowski, 1984) or existing with the right cranial caval vein (Bradley, 1902; Krahmer, 1964).

According to Hausman (1955), the left cranial caval vein was observed in cats in one case per 300 dissections. Sekeles (1982) reported its frequency at one per thousand in cats. Only a few cases of the left cranial caval vein have been described in cattle (Sekeles, 1982). The left cranial caval vein is always observed in monotremata and marsupialia (Dowd, 1969, 1974). In birds the left cranial caval vein is termed the left precaval vein. However, it does not collect blood from the heart (Lindsay, 1967).

In contrast to the reports cited above, Bertho (1964) described the left cranial caval vein as a constant vessel in pigs (30 cases), cattle (35 cases), sheep (ten cases) and deer (one case). However, his report was based on corrosion casts and gave no statistical data apart from general descriptions (‘constant’, ‘absent’, etc.)

One of the most extensive studies performed by Meinertz (1966) included 116 specimens of 76 mammalian species. The left cranial caval vein was identified in deer, horses, antelopes, elephants, bears, giraffes and European bison.

In mice (as in rats) the left cranial caval vein is a constant vessel, which is joined with the left-sided azygos vein. Several of the cardiac veins open to the left cranial caval vein. On this basis, we arbitrarily propose that the part of the left cranial caval vein, from the azygos vein mouth to the right atrium, should be named the coronary sinus.

In mice the corresponding system is composed of the left cardiac vein, which enters the coronary sinus, but with a different area of drainage. Its arrangement and distribution are very similar in rats (Halpern, 1953) and rabbits (Grant & Regnier, 1926). The course of the left cardiac vein is similar to the left marginal vein in pigs and humans (Ratajczyk-Pakalska, 1974). In marsupials, monotremes and birds the vessel, called the great cardiac vein, courses between the left atrium and the pulmonary trunk and opens to the right atrium (Lindsay, 1967; Dowd, 1969, 1974).

The caudal vein exists in higher mammals as well as marsupials and also in birds. Its course can be compared with the course of the posterior vein of the left ventricle or with the middle cardiac vein in humans. In pigs, both vessels coexist as in humans (Ratajczyk-Pakalska, 1974; Ludinghausen, 1987).

As in mice, in rats and rabbits the caudal veins (or the dorsal veins of Halpern, 1953) open to the terminal part of the left cranial caval vein or coronary sinus according to our nomenclature. In mice, however, most often there are two or three caudal veins. They often anastomose at their opening to the vascular channel, which lies on the surface of the coronary sulcus.

In marsupials, the middle cardiac vein opens to the vessel which courses around the left atrium and then enters the right atrium below the orifice of the left cranial caval vein (Dowd, 1974).

In birds, the middle cardiac vein is a prominent venous channel, which independently enters the right atrium (Lindsay, 1967).

In monotremes, the middle cardiac vein joins the right marginal vein. From this point originates the coronary vein, which enters the right atrium between the right cranial caval vein and the caudal caval vein (Dowd, 1969).

The drainage from the right side of the heart differs in various animals as compared with mice.

In several animals (Bertho, 1964) there is a large venous branch called the right marginal ventricular vein, which is similar to the right cardiac vein in mice. Such a vessel was also reported by Ludinghausen (1987) and by Ratajczyk-Pakalska (1974) in 7% of cases as a distal part of the small cardiac vein in humans. This vessel may be classified as the greatest of the anterior cardiac veins and was reported in 82% of cases (Mierzwa & Kozielec, 1975). In the literature it is also called the vein of Galen (Esperança Pina, 1975). In rabbits, a similar vessel has been reported as the right coronary vein (Grant & Regnier, 1926) collecting several branches from the right ventricle. In 20% of cases in humans it is a large channel, which collects several branches from the right ventricle (Ho et al. 2004). In pigs, it is also inconstant and has been observed in 33% of cases (Ratajczyk-Pakalska, 1974).

In rats, the pattern described by Halpern (1953) is quite similar to that in mice. In addition, in marsupials the big vessel draining the right ventricle has been reported (Dowd, 1974). In birds all veins of the right ventricle are called the small cardiac venous complex (Lindsay, 1967).

The pattern of right cardiac veins in monotremes has been discussed above. Anterior cardiac veins are very variable in humans and other animals (Esperança Pina, 1975; Mierzwa & Kozielec, 1975; Ludinghausen, 1987). In mice, vessels similar to the anterior cardiac veins termed here as cranial cardiac veins were identified as independent vessels in only four cases. In all other cases the right conal vein collected these minute branches. Halpern (1953) reported ventral cardiac veins in this location.

The system of conal veins in mice described by us is unique among the descriptions of the veins of the heart. Even in rats the pattern is different. Halpern (1953) describes the conoventricular vein, which is very similar to the large cardiac veins of marsupials, monotremes and birds (Dowd, 1969, 1974; Lindsay, 1967).

The variable system of conal veins is generally composed of the left conal vein and the right conal vein, which usually anastomose in front of the pulmonary root – the prepulmonary conal venous arch. This is similar to the arterial Vieussens anastomosis in humans. In several cases of human hearts, James (1961) describes a venous ring parallel to the Vieussens arterial ring.

The right conal vein courses to the right atrium crossing the ascending aorta on the right side, and eventually collecting cranial cardiac veins. The left conal vein enters the space between the left atrium and the pulmonary trunk, and then courses between the ascending aorta and conal surface of the atria entering the right atrium or the lower part of the right cranial caval vein. In some cases the anastomosis between the right conal vein and the left conal vein was observed between the pulmonary trunk and the ascending aorta coexisting with the prepulmonary conal venous arch. Such variation has been called the Circulus venosus coni arteriosi (CVCA). The purpose of such anastomosis in rats has been described by Halpern (1953) but only in the embryonic period as a plexus around the infundibulum of the right ventricle. The right conal vein in mice can be compared with the ventral cardiac vein of Halpern. However, the anastomoses between the right conal vein and the left cranial caval vein described by Halpern as the conoanastomotic vein in rats was observed in only a single case in the present study.

In rats, the conoventricular vein of Halpern generally resembles the left conal vein. However, the constant opening of the conoventricular vein in rats was the right cranial caval vein while the right conal vein in mice opened mainly to the right atrium.

The anastomoses between veins of the heart and systemic veins, which could be referred to as the ‘extra cardiac coronary veins of Halpern’, are observed in the left atrial vein. They coexist with a highly unusual variation – the intercaval venous arch. Such a variant has not been reported in humans or other animals.

The development of the prepulmonary conal venous arch and intercaval venous arch in mice may be compared with the superior and inferior transverse plexus, which exist around the infundibulum of the right ventricle and join the cardinal veins (Konstantinov et al. 2003). Interestingly, venous drainage of the right atrium was not visible in mice.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Ministry of Scientific Research and Information grant (#2 P05A 111 28) and internal funds of the Medical University of Warsaw.

References

- Ahmed SH, Rakhavy MT, Abdalla A, Assaad EI. The comparative anatomy of the blood supply of cardiac ventricles in the albino rat and guinea pig. J Anat. 1978;126:51–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertho E. Anatomie comparée normale des artères et des veines coronaires du coeur de différentes espèces animales. Arch Anat Hist Embryol. 1964;47:283–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogers AJJC, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Dubbeldam JA, Huysmans HS. The inadequacy of existing theories on development of the proximal coronary arteries and their connexions with the arterial trunks. Int J Cardiol. 1988;20:117–125. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(88)90321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogers AJJC, Gittenberger de Groot AC, Poelmann RE, Peault BM, Huysmans HA. Development of the origin of the coronary arteries, a matter of ingrowth or outgrowth? Anat Embryol. 1989;180:437–441. doi: 10.1007/BF00305118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley OC. A case of left anterior (superior) vena cava in the dog. Anat Anz. 1902;21:142–144. [Google Scholar]

- Cha EM, Khoury GH. Persistent left superior vena cava: radiologic and clinical significance. Radiology. 1972;103:375–381. doi: 10.1148/103.2.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dbalý J, Rychter Z. The vascular system of the chick embryo. XVI. Development of branching of coronary arteries in chick embryo with experimentally induced right-half heart hypoplasy. Folia Morph (Prague) 1966a;14:117–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dbalý J, Rychter Z. The vascular system of the chick embryo. XVII. Development of branching of coronary arteries in chick embryo with experimentally induced left-half heart hypoplasy. Folia Morph (Prague) 1966b;14:117–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dbalý J, Ošt’ádal B, Rychter Z. Development of the coronary arteries in rat embryos. Acta Anat. 1968;71:209–222. doi: 10.1159/000143186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd DA. The coronary vessels and conducting system in the heart of monotremes. Acta Anat. 1969;74:547–573. doi: 10.1159/000143418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd DA. The coronary vessels in the heart of a Marsupial Trichosorus vulpecula. Am J Anat. 1974;140:47–56. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001400104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esperança Pina JA. Morphological study on the human anterior cardiac veins, venae cordis anteriores. Acta Anat. 1975;92:145–159. doi: 10.1159/000144436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant RT, Regnier M. The comparative anatomy of the cardiac coronary vessels. Heart. 1926;13:85–317. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern MH. Extracoronary cardiac veins in the rat. Am J Anat. 1953;92:307–328. doi: 10.1002/aja.1000920205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern MH. The dual blood supply of the rat heart. Am J Anat. 1957;101:1–15. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001010102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausman SA. A venous anomaly of the domestic cat. Anat Rec. 1955;121:109–112. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091210109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho SY, Sánchez-Quintana D, Becker AE. A review of the coronary venous system: a road less traveled. Heart Rhythm. 2004;1:107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James TN. Anatomy of the Coronary Arteries. New York: Paul B. Hoeber, Inc; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinov I, Van Arsdell GS, O’Blenes S, Roy N, Campbell A. Retroaortic innominate vein with coarctation of the aorta: surgical repair and embryology review. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;15:1014–1016. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04333-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krahmer R. Über eine paarige v. cava cranialis beim schaferhund. Anat Anz. 1964;115:354–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay FEF. The cardiac veins of Gallus domesticus. J Anat. 1967;101:555–568. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludinghausen M. Clinical anatomy of cardiac veins, Vv.cardiacae. Surg Radiol Anat. 1987;9:159–168. doi: 10.1007/BF02086601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinertz T. Eine untersuchung über den sinus coronarius cordis (v.cava cran.sin.), die v.cordis media und den arcus aortae sowie den ductus (lig.) Botalli bei einer anzahl von säugetierherzen. Gegenbaurs Morph Jahrb. 1966;109:473–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mierzwa J, Kozielec T. Variations of the anterior cardiac veins and their orifices in the right atrium in man. Folia Morph (Warsz) 1975;34:125–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratajczyk-Pakalska E. Studies on the cardiac veins in man and the domestic pig. Folia Morph (Warsz) 1974;23:373–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rychter Z, Ošt’ádal B. Mechanism of the development of coronary arteries in chick embryo. Folia Morph (Prague) 1971;19:113–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekeles E. Double cranial vena cava in a cow: case report and review of the literature. Zbl Vet Med A. 1982;29:494–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0442.1982.tb01811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanowski T. The left cranial vena cava in dog. Folia Morph (Warsz) 1984;43:327–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura H, Ho SY, Anderson RH, et al. The surgical anatomy of coronary venous return in hearts with isometric atrial appendages. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;110:436–444. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(95)70240-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura H, Ho SY, Anderson RH, et al. Surgical anatomy of the coronary circulation in hearts with discordant atrioventricular connections. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1996;10:194–200. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(96)80296-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincentini CA, Orsi AM, Mello Dias S. Observations anatomiques sur la vascularisation artérielle coronarienne chez le cobaye (Cavia porcellus, L.) Anat Anzeiger. 1991;172:209–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrancken Peeters MPFM, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Mentink MMT, Hungerford JE, Little CD, Poelmann RE. Differences in development of coronary arteries and veins. Cardiovasc Res. 1997a;36:101–110. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrancken Peeters MPFM, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Mentink MMT, Hungerford JE, Little CD, Poelmann RE. The development of the coronary vessels and their differentiation into arteries and veins in the embryonic quail heart. Dev Dyn. 1997b;208:338–348. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199703)208:3<338::AID-AJA5>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb S, Brown NA, Anderson RH. The structure of the mouse heart in late fetal stages. Anat Embryol. 1996;194:37–47. doi: 10.1007/BF00196313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb S, Brown NA, Anderson RH. Formation of the atrioventricular septal structures in the normal mouse. Circ Res. 1998;82:645–656. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.6.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyrost P. A rare case of left anterior vena cava (vena cava cranialis persistens) in a dog. Folia Morph (Warsz) 1968;27:129–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]