Abstract

The architecture of the diaphyseal bone is closely correlated with the cortical vessel network, whose pattern develops in the course of growth. Various methods have been applied to clarify the three-dimensional anatomy of the cortical canal system, but there is still disagreement about the geometry, blood supply, flux dynamics and factors controlling canal geometry during bone growth and remodeling. A modification of the currently employed dye-injection method was applied to study the vessel network of the whole hemi-shaft of the rabbit femur in mature bones (8-month-old rabbits) and growing bones (1.5-month-old rabbits). The cortical vascular tree of the hemi-shaft of the femur was injected with black China ink and observed in full-thickness specimens of the cortex. The same specimens were then processed for histology. A comparative study of the middle diaphysis (mid-shaft) with the distal extremity (distal shaft) was performed in both young and old rabbit femurs. The longitudinally oriented pattern of the vessel network was seen to develop in the diaphysis of mature femurs, while at the extremity of the shaft of the same specimen the network showed a reticular organization without a dominant polarization. The vessels were significantly higher in the mid-shaft than in the distal shaft of the old femurs (P < 0.0001), as was their diameter (P < 0.05). In the group of young rabbits at mid-shaft level the longitudinally oriented pattern of the vessel network was not yet completely developed, without their being significant differences in length and diameter between the mid-shaft and distal shaft. The differentiation of the mid-shaft from the distal shaft was confirmed histologically by the presence, in the latter, of longitudinal calcified cartilage septa between osteons. This pattern of structural organization and development of the intracortical vascular network has not been previously reported. The cells primarily involved in polarization of the remodeling process were the osteoclasts at the top of the cutting cones advancing from the proximal and distal metaphyses toward the mid-shaft. This suggests, first, a relationship with the longitudinally oriented structures already present in the cortex near the metaphysis (the calcified cartilage septa) and then with the columns of interosteonic breccia, which were formed as a secondary effect of the longitudinal polarization of the remodeling process. Our observations did not enable us to substantiate the model of two different systems, one of longitudinal vessels (Havers) and the other of connecting transversal vessels (Volkmann), but suggested instead that there is a network whose loops lengthen in the direction of the major bone axis in the course of growth and secondary modeling. The associated morphology supported the view that the type of structural organization of the tubular bone cortex is primarily determined by an inherited constitutional factor rather than by mechanical strains.

Keywords: bone architecture, cortical bone, cortical vessel network, Havers’ and Volkmann's canals

Introduction

There is close correlation between the architecture of diaphyseal, cortical bone and the organization of the vascular network inside the cortex; the former is built up during growth (modeling), but it is continuously rearranged even in the mature bone (physiological remodeling), and both processes are controlled by the vessels’ progression and distribution inside the cortex.

The three-dimensional anatomy of the Havers system and of the vascular network has been extensively investigated, using serial histology in longitudinal and transverse planes (Cohen & Harris, 1958), perfusion of the microscopic cavities with dyes (Filogamo, 1946; Vasciaveo & Bartoli, 1961; Albu et al. 1973), x-ray micro-angiographic techniques (Brookes & Revell, 1998), histology with dye-injection techniques (Morgan, 1959; Nelson et al. 1960; Hert & Hladíková, 1961; Bruyn et al. 1970; Trias & Fery, 1979; Marotti et al. 1980; Lopez-Curto et al. 1980; Brookes & Revell, 1998), bone clearance of bone-seeking isotope techniques (Ray et al. 1967; Kane, 1968; Kelly, 1968), and scanning electron microscopy combined with corrosion casting techniques (Othani et al. 1982; Skawina et al. 1994).

The general pattern indicated by these studies consists of a main medullary system supplying the endosteal surface of the shaft and most of the cortical bone, and of a periosteal system supplying the periosteum and the outer cortex. Both of them, after closure of the epiphyseal growth plates, merge with the metaphyseal and epiphyseal systems. Venous drainage is believed to occur mostly through the medullary sinusoids and the central vein; however, the flux dynamics of this complex vascular system has been shown to have considerable flexibility in relation to the modification of physiological as well as pathological conditions of the bone (Rhinelander, 1968).

There is also controversy concerning the blood supply dynamics and the geometry of the vessel network, and the morphology of the bone canal systems. Among the debated questions are the relationship between the cortical and marrow vascular systems, the length and morphometry of the Havers canals, the number and types of vessels inside the Havers canals, and the factors controlling the canal geometry during bone growth and later in the remodeling process.

A sufficiently detailed three-dimensional study of the Havers system (or the secondary osteon system) is difficult to achieve because longitudinal histological sections can only include a limited segment of the longitudinal canals, and serial transversal sections can only follow the same for a small tract of the shaft. Only histology with dye injection gives a satisfactory bi-dimensional representation of the cortical vascular network, if thick sections are employed and water-soluble dyes are injected (a low-viscosity solution is necessary to inject the fine intra-cortical vessels).

In the present study on the rabbit diaphysis, the usual histology dye-injection method was modified in order to extend the observation of the vascular network to the whole hemi-shaft of the femur, with the possibility of later applying standard histology on cut slides of the same specimen of cortical bone. The low-enlargement panoramic view was able to differentiate the intracortical vascular patterns of the mid-shaft and distal shaft and its modulation during the growth in length of the bone.

It has already been documented that tubular bone growth is characterized by a developmental history, with the formation of different models of collagen fiber organization (woven-fibred bone, primary osteons, surface bone and secondary osteons) with a definite relationship of the fibre pattern with the geometry of the vascular canals (Hert & Hladíková, 1961; Smith, 1959). The observations in the model employed were related to the pattern of secondary osteon formation.

Material and methods

The study was carried out on the femurs of eight male New Zealand white rabbits (Stefano Morini, S. Polo d’Enza, Reggio Emilia, Italy). Four were adult rabbits (age 8 months) with a body weight between 3.0 and 3.5 kg, four were young rabbits aged 1.5 months and weighing about 300 g. The animals were housed in individual cages with food and water ad libitumand kept in an animal house at a constant temperature of 22 °C with 12 h alternating light-dark cycle. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and the number of animals used. The experimental procedures were approved by the Italian Health Ministry.

Each rabbit received 30 mg kg−1 day−1 of tetracycline for 3 days before the experiment. To inject the vascular tree of the lower limbs, all rabbits were anaesthetized with ketamine cloridrate (Imagel) and xilazine (Rompum); the aorta and cava vein were exposed through a midline abdominal incision and a 1.5 mm catheter was inserted in the distal part of the aorta. The artery was then tightly ligated with two knots around the catheter, and a slow continuous infusion of a heparinized saline solution was performed through the cannulated artery; the cava vein was then clamped with Klammer forceps and 300 mL of black China ink water-solution (60%) was injected with a hand syringe at a pressure of 150–200 mmHg until the lower limbs were completely perfused. Just before China ink injection, the rabbits were killed with an overdose of the anaesthetic.

The skin of the limbs was excised and the femurs were dissected, leaving the periosteum intact, before being fixed in neutral formaline (10%).

Half of the left femurs were embedded undecalcified in Technovit resin (Kultzer & Co. GmgH, Werheim, Germany), and 200 µm thick sections in a plane perpendicular to the major axis of the bone were prepared with the cutting-grinding technique (Exact Apparate Bau, Norderstadt, Germany); unstained slides were observed in incident fluorescent light with a Leitz Aristophot (Leitz GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) microscope.

The other half were decalcified and cut in planes perpendicular to the major axis of the femur at levels corresponding to the mid-shaft and distal shaft or in the mid-sagittal plane at the same levels; these sections, stained with standard haematoxylin-eosin, were used for microscopic study in bright field and phase contrast.

The eight right femurs (four from the old group, and four from the young group) were decalcified in EDTA (10%) at 37 °C for 2 months: the diaphysis was parted from the proximal and distal epiphyses with a hand-made cut, performed 4 mm above the distal growth-plate cartilage and 10 mm below the tip of the greater trochanter (the distal growth-plate cartilage in the old rabbits was thinner than in the young animals, but was clearly visible in the dissected specimen). These cylinders were further transversely cut at the midpoint of the shaft, and the distal half was split longitudinally into a dorsal and ventral half; the marrow and periosteal soft tissues were removed with a scalpel, and then the cylinders were abundantly washed with a formalin solution (2%), in which the specimens were kept until microscopic observation.

On the dorsal surface of the hemishaft the periosteum was completely detached with a scalpel, while this procedure was not satisfactory for the ventral hemishaft, which turned out to be unsuitable for microscopic study due to the presence of stained soft tissues embedded in the rough posterior wall of the femur.

The specimens of the full-thickness cortex selected for observation were air-dried for about three minutes. Then, before they had lost their plasticity, they were pressed flat between two glass slides tightly secured by adhesive tape at the extremities (Fig. 1). They were observed unstained in bright field with an Olympus BX 51 microscope (Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan), with objectives PlanApo N 1.25×, Plan N 4× and U Plan FL N 10×. Digital images were captured with a telecamera Colorview IIIu (Soft Imaging System GmbH, Münster, Germany) mounted on the microscope. The lower-enlargement images (12.5×) were used for an overview of the general pattern of the vessel network; the higher-enlargement images were used for the measurements (40×) and detailed examination (100×).

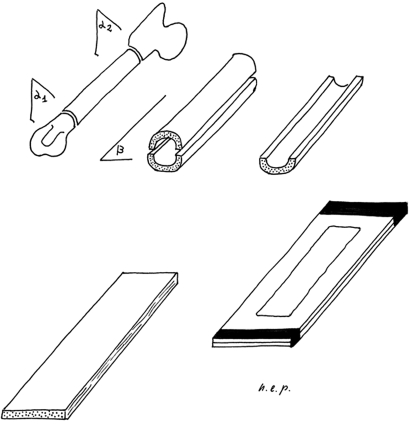

Fig. 1.

Method for observation of the full-thickness hemishaft. α1: distal transverse section 4 mm above the distal growth-plate cartilage. α2: proximal transversal section 10 mm below the tip of the great trochanter. β: mid-frontal plane of the femur diaphysis.

Afterwards the tissue specimens were removed from the glass slides and stored in the formalin solution. From each dorsal hemi-shaft specimen both the proximal end (5 mm thick, marked as mid-shaft) and the distal (5 mm thick, marked as distal shaft) were cut. They were processed and embedded in paraffin blocks oriented so that the microtome would cut slides in a plane perpendicular to the major axis of the bone; several sections, 10 µm thick, were stained with haematoxylin-eosin and mounted on glass slides.

Morphometry

Five 40× images of the mid-shaft and distal-shaft vessel network of each femur were selected so as to cover most of the area corresponding to the mid-shaft and distal-shaft bands; measurements were performed utilizing the software Cell (Soft Imaging System GmbH). The following parameters were evaluated.

(1) Length of vessels, measured as the distance between two contiguous intersections of the network. In the mid-shaft images, we only evaluated those vessels which remained in the plane of focus between two intersections, or those in focus between the two opposite borders of the image or between a border and an intersection.

(2) Diameter of vessels, measured at the midpoint between the reference points for length measurement. Therefore the values for each femur were the mean of five fields. The five best (without technical artefacts) mid-shaft and distal-shaft sections of each specimen were selected for evaluation. From each slide, three fields were captured, representing the middle, right and left extremity of the cortex and including either the endosteal or the periosteal surfaces.

The following parameters were also evaluated: (1) cortical thickness (mm); (2) density of vascular channels (n/mm−2); and (3) mean area of vascular canals (mm2). The values expressed for each rabbit were the means of fifteen fields on five levels.

Statistical analysis

The length and diameter of the dorsal cortex network vessels of old and young femurs were compared separately (mid-shaft versus distal shaft). The cortical thickness, density and mean area of the vascular canals were compared in the same way. Paired Student t test was used.

Results

The intracortical vessel network (full-thickness cortex) was imaged using a comparatively new method. Low-enlargement (12.5×) observation allowed us to keep the whole bone specimen in focus, and gave a general view of the network of intracortical vessels injected by black China dye. There was a remarkable superimposition of single vessel outlines; however, a clear parallel pattern was evident in the mid-shaft of the old femur group (Fig. 2B) in contrast with the reticular design of the distal shaft (Fig. 2A). The mid-shaft of the young femur group also showed a reticular pattern but with more elongated loops (Fig. 2C). Intravascular dye injection enhanced the morphometric assessment of the diameters of the network vessels, because measurements were performed directly on vessels rather than on the bony canal.

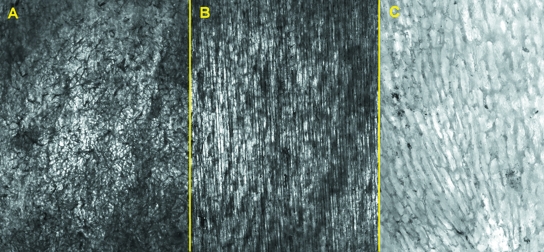

Fig. 2.

Low-power view of compared hemishaft levels (see text for delimitation): (A) old, distal-shaft (12.5×) reticular pattern of the vessel network; (B) old, mid-shaft (12.5×) longitudinal arrangement of cortical vessels is evident; (C) young, midshaft (40×) showing the vessels network with a reticular pattern, but loops show initial polarization along the longitudinal axis.

Observation at higher enlargements (40× and 100×) focused a layer of the cortex of 230 and 36 µm respectively and allowed a better definition of the individual vessels and their branches, which were followed for most of the microscopic field (Fig. 3A,B). The length of the vessels was significantly higher in the mid-shaft than in the distal shaft of the old femurs. No significant difference was observed in young femurs. Vessel diameter was significantly lower in the distal shaft of the old femurs and not significant in the young ones (Table 1).

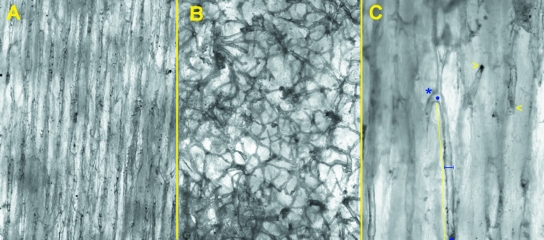

Fig. 3.

Higher enlargement of unstained, full-thickness cortex utilized for measurements: (A) old, mid-shaft (40×); (B) old, distal shaft (40×); (C) old, mid-shaft (100×) examples of measurements: internodal length is indicated by full line; vessel diameter by truncated segment; blind ends (asterisk) and short-radius bend (arrows).

Table 1.

Length and diameter of the dorsal cortex network vessels injected by black China ink in the mid-shaft and distal-shaft of old and young rabbits. Comparison between mid-shaft and distal-shaft in old and young femurs

| Rabbits | Old (n = 4) | Young (n = 4) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rabbits | ||||

| Right femur | Mid-shaft | Distal shaft | Mid-shaft | Distal shaft |

| Length (µm) | 120.1 ± 160.9 | 269.7 ± 76.53 | 199.4 ± 35.57 | 169.9 ± 30.27 |

| P < 0.0001 | P = 0.246 | |||

| Diameter (µm) | 39 ± 2.4 | 26.31 ± 5.05 | 27 ± 1.46 | 26.71 ± 2.89 |

| P < 0.05 | P = 0.861 | |||

The course of the vessels between bifurcations was in general straight in both the mid-shaft and the distal shaft; however, short radius bends or blind ends were occasionally observed. The latter could be differentiated by the sharp, truncated profile of the vessel end, which was different from the shaded and flute-beak-like aspect of those vessels transpassing out of the focal plane (Fig. 3C). In the same specimen blind ends facing either the proximal and distal extremities of the bone were present.

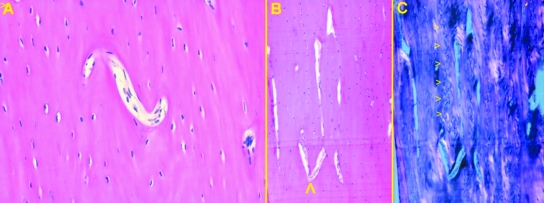

Transversal histological sections showed the typical osteonal pattern: the segment arbitrarily delimited as the distal shaft was characterized by the presence of calcified cartilage between osteons in both old and young groups (Fig. 4A); longitudinal sections cut in the left femur showed that calcified cartilage septa had the same longitudinal orientation of the surrounding osteons (Fig. 4B). On the contrary, the segment referred to as the mid-shaft lacked them, and the space between the osteons was filled by remnants of old osteons known as breccia (Fig. 4C).

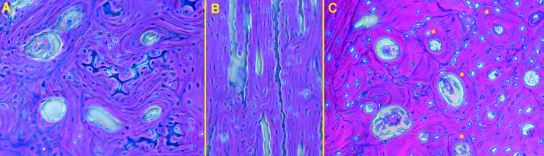

Fig. 4.

Haematoxylin-eosin (200×), phase contrast: (A) old, transversal section at distal-shaft level showing the calcified cartilage septa between osteons; (B) old, longitudinal section at distal-shaft level showing the parallel arrangement of calcified septa and osteons; (C) old, transversal section at mid-shaft level showing interosteonic breccia formation between old and most recently developed osteons [those with an uninterrupted cement line at periphery (marked by asterisks)].

No significant differences in cortical thickness were observed between the mid-shaft and distal shaft in both old and young groups. The density of the vascular canals was significantly higher in the mid-shaft than in the distal shaft of old rabbits; no significant difference was observed in the young rabbits. The mean area of the vascular canals did not show significant differences in either group (Table 2). The latter parameter represented either the central vascular space of the most recently completed osteons, that of old remodeled osteons, and the larger resorption lacunae of osteons actually in different phases of formation of the lamellar structure.

Table 2.

Cortical thickness, density and mean area of vascular canals in the mid-shaft and distal-shaft of old and young rabbits. Comparison between mid-shaft and distal-shaft in old and young femurs

| Rabbits | Old (n = 4) | Young (n = 4) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rabbits | ||||

| Right femur | Mid-shaft | Distal shaft | Mid-shaft | Distal-shaft |

| Cortical thickness (mm) | 0.456 ± 0.06 | 0.606 ± 0.12 | 0.584 ± 0.09 | 0.462 ± 0.02 |

| P = 0.159 | P = 0.093 | |||

| Density V.C. (n/mm−2) | 142.3 ± 34.41 | 84.13 ± 22.13 | 112 ± 25.22 | 91.25 ± 15.41 |

| P = 0.05 | P = 0.258 | |||

| Mean area V.C. (mm2) | 0.341 ± 0.34 | 0.226 ± 0.1 | 0.928 ± 0.13 | 0.827 ± 0.21 |

| P = 0.609 | P = 0.307 | |||

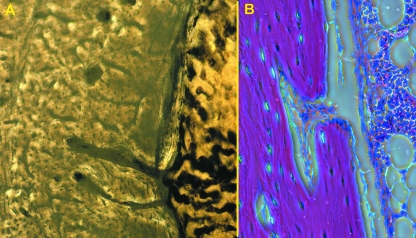

Histological sections of the left femurs, in both the transverse and longitudinal planes (not used for morphometrical assessment), enabled us to document the bifurcations and short-radius bends of longitudinally oriented Havers canals of the old mid-shafts as observed in the injected vessels (Fig. 5A,B). In the longitudinal sections, observed in polarized light, interosteonic breccia showed a columnar arrangement (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Haematoxylin-eosin, old, longitudinal sections: (A) (100×) short-radius bend of a cortical canal, as documented by the injection method; (B) (40×) longitudinal cortical canals with bifurcation directed upwards (arrow); (C) (40×) same field of (B) in polarized light showing the columnar arrangement of interosteonic breccia as result of longitudinal polarization of secondary osteons (arrows).

The most evident connection of the cortical vascular system was with the endosteal vessels (Fig. 6A). When observed in the longitudinal plane, those in the distal shaft crossed the endosteal surface with acute angles and were directed toward the mid-diaphysis, while in the mid-shaft they crossed the endosteal surface with 90° angles, and occasionally they were observed to divide into two branches in a longitudinal direction (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Old, mid-shaft: (A) (40×) unstained, thick transverse section, showing connections of cortical vessels with marrow sinusoids; (B) (100×) haematoxylin-eosin, longitudinal section showing a canal opening in the medullary central space.

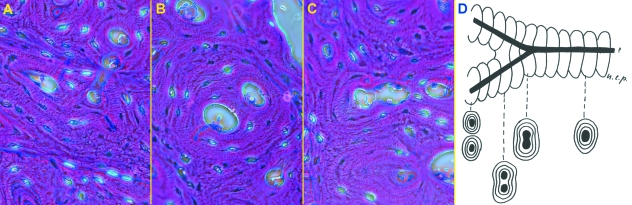

At the sites of intracortical bifurcation, the dividing vessels appeared surrounded for a certain distance by a unique system of concentric lamellae, which then structured in two different osteons around the diverging vessels (Fig. 7A–C). These particular features and the blind ends were indicative of the cutting cones’ direction of progression in the remodeling process (Fig. 7D). In the mid-shaft, vascular canals were preferably dug along the major axis of the diaphysis, either proximally or distally; sudden changes in direction (short radius bends) were rare.

Fig. 7.

Old, mid-shaft; the direction of canals progression is documented by the lamellar pattern at bifurcations: (A) (200×) haematoxylin-eosin, phase contrast: the diverging branches have formed two independent osteons; (B, C) (200×) haematoxylin-eosin, phase contrast: the canal form two branches surrounded by a single lamellar system; (D) direction of progression deduced by bifurcations structure.

There was wide variation in the dimensions of the vascular canals, which correlated to the degree of lamellar organization of the corresponding osteon. The most recent developing osteons (those with the wide central vascular canal) were more frequently observed in the subendosteal and subperiosteal parts of the cortex.

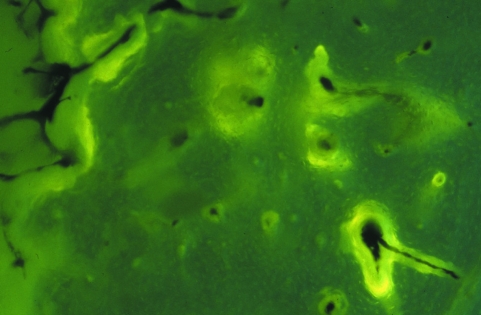

Fluorescent labeling revealed the bone surfaces where active bone deposition by osteoblasts was occurring: periosteal and endosteal bands were present, as were labelled osteons scattered on the whole surface of the transversal sections without any recognizable topography. Occasionally it was possible to document the fluorescent label contouring the divergence of vessels at the bifurcation point (Fig. 8), as expected by the cells’ disposition inside the advancing cutting cone.

Fig. 8.

Old mid-shaft (100×) incident fluorescent light, transverse section showing a subendosteal portion of the cortex with scattered, labeled osteons. In the right, bottom corner bifurcation of a vascular canal is present.

Discussion

Our knowledge of the osteonal structure of tubular bone diaphyses derives from the classic histological studies which already showed the central role of the Havers and Volkmann canal network for the distribution of the blood supply inside the mass of compact bone of the diaphysis (Ham, 1957). Ultrastructural studies have clarified the canalicular interconnections between the cytoplasmic prolongments of osteocytes inside the osteon (Robinson, 1981). Further studies have been carried out to investigate the role of circulation in bone organization and physiology (Currey, 2002; McCarthy, 2007).

An initial general interpretation of the architecture of the cortex can be read as a structural organization functional to the need of support of the metabolic demands of osteocytes inside cortical bone.

An alternative point of view is that the lamellar organization of bones responds to mechanical needs, as theorized by Wolff's law (Wolff, 1884) and by a large number of studies in the field of biomechanics (Lanyon, 1974; Lanyon & Bourn, 1979; Frost, 1980).

The findings of this study rest on the possibility of extending through the transilluminated full cortex the observation of a larger field of the intracortical vascular network, which provided better evidence of the spatial orientation of the vessels and of the modalities of intersections.

Old femurs

There was a parallel pattern of mid-shaft vessels, in contrast to the reticular arrangement of the distal-shaft vessels. This was evident from simple qualitative observation, and further confirmed by the significant increase in the longitudinal length of the vessel network loops.

Young femurs

The mid-shaft vessels showed a reticular arrangement, though the loops of the network suggested a tendency to a more elongated shape along the longitudinal axis than those of the corresponding distal shaft. However, this qualitative observation did not correspond to a statistically significant increase in length. These observations suggest that the ordered longitudinal pattern of the vessel network is progressively established during growth.

These findings did not allow us to substantiate the concept of two different systems, one of longitudinal vessels (Havers) and the other of connecting transversal vessels (Volkmann), because neither the geometry of the network, the diameter of the vessels, nor the other morphological aspects could be used to distinguish between the two systems. The model suggested by this study is that of a network (formed by primary modeling) whose loops have no prevailing dimension in the spatial planes; polarization occurs in secondary modeling and growth in length of the diaphysis, when the loops of the network become lengthened in the direction of the major bone axis. Consequently the loops assume the figure of a quadrilateral with two very long sides, corresponding to the Havers canals of classic anatomy, while the short arms tend to became positioned in an oblique or transversal plane (Volkmann's canal).

Length measurements of the cortical longitudinal canals (segments between bifurcations) have been performed in previous studies: 3–6 mm, up to 10 in 10% of osteons of human bones (Filogamo, 1946); max. 3 mm in a human phalanx (Koltzer, 1951); mean 0.8 mm, range 0.4–1.2, in human jaw cortex (Dempster & Enlow, 1959); 2 mm or more in bovine metacarpals (Vasciaveo & Bartoli, 1961); mean 0.48 mm, range 0.001–2.1, in dog bones (Cohen & Harris, 1958). It can be observed that there is wide variability of the data reported, which could be related to the different species or type of bones studied, but also to methodology, because in no case was there any mention of the shaft level of the cortex examined.

All the quoted studies measured the length of the longitudinal bone canal, while in the present study measurements were performed directly on vessels inside the vascular canal, which made it possible to extend the observation to the vessel diameter.

Length measurements as performed here on the full-thickness hemicortex are affected by a bias due to the projectional effect, because the segments measured do not lie entirely on a plane parallel to the visual plane. The error margin is conditioned by the depth of field of the microscope objective and by the length of the segment measured; the shorter that the latter is, the larger the error may be. As a consequence, the measurements of the internodal length of the distal-shaft vessels (the shorter) were underestimated. It was calculated that the highest error margin could be 122.6% for the distal-shaft vessels, and 3.7% for the mid-shaft vessels. However, even considering this margin of error, the differences between the length of the mid-shaft and distal-shaft vessels were significant (P < 0.001).

The distinction of the diaphysis in the mid-shaft and distal-shaft was founded on an arbitrary assignment; however, it found histological validation by the observation of calcified cartilage septa between osteons in the distal diaphysis. There is not a clear-cut level of transition, but it can be referred with a sufficient degree of precision to 1/5 of the total length of the diaphysis in both old and young femurs.

The study was limited to the dorsal half diaphyses of old and young femurs because the opposite ventral hemishaft turned out to be unsuitable for observation with this technique, due to the superimposition of artefacts from the dye deposits on the rough surface of the posterior wall of the femur, which could not be cleaned even by mechanical scratching. However, whole transverse sections carried out in the left femurs did not show significant differences in the general lamellar organization between the two sectors of the shaft; since the osteonal architecture of the cortex is closely correlated to the pattern of vascular distribution, the model of the vascular network proposed can be extended to the whole diaphysis.

Morphometric analysis of the canal system did not show significant differences in the sum of the areas of all canals in a transversal section between mid-shaft and distal shaft, but the density of the same was higher in the mid-shaft of old femurs. There were large variations in the vascular canal (Havers) area in transversal sections which were related to the actual remodeling status of that segment of the cortex: the large, rounded or polycyclic holes corresponded to the most recent developing osteons, while the Havers canals of structured osteons were smaller, with a more uniform area and a regular, rounded or oval shape.

The discrepancy between the density and vascular canal area in the distal-shaft and mid-shaft of old femurs may be related to the more advanced state of remodeling in this group than in young rabbits, while in the latter remodeling is more uniformly distributed at all levels of the shaft.

Another explanation for the higher density of the vascular canals in old mid-shafts may be related to longitudinal polarization of remodeling with canals advancing from the proximal and distal metaphyses. At the mid-shaft level there is interdigitation of canals advancing in opposite directions.

The geometry of the vessel network is superimposable to the system of canals, but it cannot be ruled out that occasionally a canal may be empty. This does not invalidate the former statement, because of the mode of formation of the canal system, with the osteoclasts of the cutting cones which dig the tunnel and are followed by the advancing vessel (Shenk & Willenegger, 1964, 1967). Therefore it is possible to state that the osteonal architecture of the shaft is determined by the direction of progression of the cutting cones and in the first place by the osteoclasts present on the top.

In the mid-shaft of old diaphyses the presence of blind ends and bifurcations gives a clue to the direction of the forming Havers canals, which are oriented either toward the proximal and the distal metaphyses independently from the force of gravity or other strains normally present in the course of the bone development.

The same bidirectional behaviour has been observed with the cutting cones moving across experimental osteotomies of the shaft rigidly fixed with plates and screws (Shenk & Willenegger, 1964).

It may be questioned what type of signal can steer the osteoclasts, backed by the vessel, at the front of the cutting cone. The mechanical model tried to answer this question concerning the regular, geometric structure of the diaphysis with the effects of strains on the living tissue (Frost, 1980), but no validation supported by sufficiently detailed morphological and morphometrical observations has ever been presented.

Histology, on the other hand, can provide some clues: longitudinal calcified cartilage septa derived from the metaphyseal growth plate cartilage are observed to persist for a certain depth in the diaphysis between osteons; the suggestion put forward by Müller (1858) and by Ranvier (1875) that the vertical bars in the growth plate cartilage impose a similar order on endochondral bone trabeculae, contradicted by others (Brookes, 1963), should be shifted from the metaphyseal trabeculae to the osteonal polarization from the extremities of the diaphysis toward the mid-shaft. The latter was observed to progress during bone growth, and in this context – as the longitudinal arrangement of osteons increases – the interosteonic breccia is modeled in a columnar pattern. In the old diaphyses both aspects were documented in this study, suggesting that chemiotaxis exerted by acellular calcified cartilage or the avascular bone matrix of the breccia can guide osteoclast advancement in the longitudinal direction. This hypothesis is consistent with the common observation that necrotic bone recalls osteoclasts and is remodeled faster than the surrounding healthy bone. Currey (1960) suggested that the metabolic conditions of osteocytes inside osteonic bone were dependent on the distance of these bone cells from the nearest vascular canal, and he identified the relative metabolic deficiency as the factor controlling the structural modeling of bone. In more general terms the chemiotaxis hypothesis rests on the observation of columnar structures, either the calcified cartilage inclusions or the columns of interosteonic breccia formed by fragments of lamellae which have lost their main blood source from their own central vessel.

According to this thesis the longitudinal architecture of the midshaft osteonal system develops progressively with the growth in length of the bone, and is controlled by an inherited constitutional factor.

This type of structural organization is primarily functional to the needs of metabolic supply to the cells located inside the compact and hard matrix of the diaphyseal bone; secondarily, it also represents a strong mechanical structure capable of accomplishing its support function.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contribution of Drs Elisa Borsani and Pierfrancesco Bettinsoli for their contribution to preparation of histological slides.

References

- Albu I, Georgia R, Stoica E, Giurgiu T, Pop V. Le sistème des canaux de la couche compacte diaphysaire des os longs chez l’homme. Acta Anat. 1973;84:43–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes M, Revell WJ. Blood supply of bone scientific aspects. London: Springer; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Brookes M. Cortical vascularization and growth in fetal tubular bones. J Anat. 1963;97:597–609. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruyn PPH, Breen PC, Thomas TB. The microcirculation of the bone marrow. Anat Rec. 1970;168:55–68. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091680105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Harris WH. The three-dimensional anatomy of haversian systems. J Bone J Surg Am. 1958;40-A:419–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currey JD. Differences in the blood supply of bones of different histological types. Anat J micr Sci. 1960;101:351–370. [Google Scholar]

- Currey JD. Bones: structure and mechanisms. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dempster WT, Enlow DH. Patterns of vascular channels in the cortex of the human mandible. Anat Rec. 1959;135:189–205. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091350305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filogamo G. La forme et la taille des osteons chez quelques mammifères. Arch Biol. 1946;57:137–143. [Google Scholar]

- Frost HM. Skeletal physiology and bone remodelling in fundamental and clinical bone physiology. Philadelphia: JB Lippincot Co; 1980. pp. 208–241. [Google Scholar]

- Ham AW. Histologg. Philadelphia: JB Lippincot Co; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Hert J, Hladíková J. Die gefässversorgung des haversschen knochens. Acta Anat. 1961;45:344–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane WJ. Fundamental concepts in bone-blood flow studies. J Bone J Surg. 1968;50-A:801–811. doi: 10.2106/00004623-196850040-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly PJ. Anatomy, physiology, and pathology of the blood supply of bones. J Bone J Surg. 1968;50-A:766–783. doi: 10.2106/00004623-196850040-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koltzer II. Studie zur ausseren Form der Osteone. Zeitschr f Anat Und Entw. 1951;115:584–591. [Google Scholar]

- Lanyon LE, Bourn S. The influence of mechanical function on the development and remodelling of the tibia. J Bone J Surg. 1979;61A:263–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanyon LE. Experimental support for the trajectorial theory of bone structure. J Bone J Surg. 1974;56A:160–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Curto JA, Bassingthwaighte JB, Kelly P. Anatomy of the microvascular of the tibial diaphysis of the adult dog. J Bone J Surg A. 1980;62-A:1362–1369. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marotti G, Zambonin Zallone A. Changes in the vascular network during the formation of haversian systems. Acta Anat. 1980;106:84–100. doi: 10.1159/000145171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy I. The physiology of bone blood flow: a review. J Bone J Surg. 2007;88A(Suppl. 3):4–9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan JD. Blood supply of growing rabbit's tibia. J Bone J Surg. 1959;41-B:185–203. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.41B1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller H. Über die entwichling der knochen substanz nebst bemerkenger über der bau rachitisher knochen. Z Wiss Zool. 1858;9:147–233. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson G, Kelly P, Peterson LFA, Janes JM. Blood supply of the human tibia. J Bone J Surg. 1960;42-A:625–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Othani O, Gannon B, Othsuka A, Murakami T. The microvasculature of bone and especially of bone marrow as studied by scanning electron microscopy of vascular casts – a review. Scanning Elect Microsc. 1982;I:427–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranvier L. Traité technique d’histologie. Paris: F. Savy; 1875. [Google Scholar]

- Ray RD, Aouad R, Kawabata M. Experimental study of peripheral circulation and bone growth. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1967;52:221–232. doi: 10.1097/00003086-196700520-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhinelander F. The normal microcirculation of diaphyseal cortex and its response to fracture. J Bone J Surg A. 1968;50-A:784–800. doi: 10.2106/00004623-196850040-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson RA. Metastructure of the osteons. Histo Morph Bewegugs App. 1981;1:37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Shenk R, Willenegger H. Zur histology der primären knochen heilung. Longenbecks Arch Chir. 1964;308:440–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenk R, Willenegger H. Morphological findings in primary fracture healing. Symp Biol Hung. 1967;7:75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Skawina A, Litwin JA, Gorczyca J, Miodoński AJ. The vascular system of human fetal long bones: a scanning electron microscope study of corrosion casts. J Anat. 1994;185:369–376. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JW. Collagen fibre patterns in mammalian bone. J Anat. 1959;94:329–344. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trias A, Fery A. Cortical circulation of long bones. J Bone J Surg. 1979;61-A:1052–1059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasciaveo F, Bartoli E. Vascular channels and resorption cavities in tha long bone cortex. The bovine bone. Acta Anat. 1961;47:1–2. doi: 10.1159/000141798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff J. Das Gesetz der transformation der inneren architecture der knochen bei pathologischen veränderungen der äusseren knochenform. Berlin Akad. d. Wissenschaften. 1884. May 1884.