Abstract

Normal fetal development is dependent on adequate placental blood perfusion. The functional role of the placenta takes place mainly in the capillary system; however, ultrasound imaging of fetal blood flow is commonly performed on the umbilical artery, or on its first branches over the chorionic plate. The objective of this study was to evaluate the structural organization of the feto-placental vasculature of the chorionic plate. Casting of the placental vasculature was performed on 15 full-term placentas using a dental polymer mixed with colored ink. Observations of the cast models revealed that the branching architecture of the chorionic vessel is a combination of dichotomous and monopodial patterns, where the first two to three generations are always of a dichotomous nature. Analysis of the daughter-to-mother diameter ratios in the chorionic vessels provided a maximum in the range of 0.6–0.8 for the dichotomous branches, whereas in monopodial branches it was in the range of 0.1–0.3. Similar to previous studies, this study reveals that the vasculature architecture is mostly monopodial for the marginal cord insertion and mostly dichotomous for the central insertion. The more marginal the umbilical cord insertion is on the chorionic plate, the more monopodial branching patterns are created to compensate the dichotomous pattern deficiency to perfuse peripheral placental territories.

Keywords: arterial network, blood vessels, dichotomous and monopodial patterns, placenta, vascular corrosion casting

Introduction

Normal fetal development is largely dependent on adequate placental blood perfusion. The structural anatomy of the fetal vasculature of the human placenta has been investigated post delivery using various techniques such as latex or plastic casts, injection of gelatin dye, microscopy and angiography (Lee & Yeh, 1983, 1986; Leiser et al. 1985, 1997; Mu et al. 2001; Ullberg et al. 2001; De Paepe et al. 2002). Power Doppler and three-dimensional sonography have been utilized for in vivo imaging of the placental vasculature (Pretorius et al. 1998; Raio et al. 2001). These studies revealed that the feto-placental vasculature is composed of large vessels that branch from the umbilical vessels at the umbilical insertion and traverse the chorionic plate. Smaller arteries branch from the chorionic vessels and enter the placenta to constitute the cotyledon vessels (Arts, 1961) or the intraplacental (IP) vessels (Mu et al. 2001) that perfuse the cotyledons. The branching pattern of the chorionic vessels was defined as disperse for a branching network that courses from a central cord insertion, and magistral for branching vessels that course from a marginal cord insertion to the opposite edge (Kishore & Sarkar, 1967).

Feto-maternal exchange of gases, nutrition and wastes takes place mainly in the capillary system of each cotyledon and therefore comprehensive investigations were conducted to explore the geometry of peripheral generations within the cotyledons (Arts, 1961; Habashi et al. 1983; Burton, 1987; Castellucci et al. 1990; Demir et al. 1997; Kingdom et al. 1997). Diagnosis of fetal condition is commonly performed by Doppler ultrasonography of umbilical arterial blood flow as close as possible to the umbilical cord insertion in the placenta (Yagel et al. 1999a; Mine et al. 2001). Recently, it was suggested to evaluate fetal blood flow on the chorionic surface to detect impaired blood flow within the capillaries (Kirkinen et al. 1994; Yagel et al. 1999b). However, detailed information on the branching pattern of chorionic blood vessels is incomplete. In this work we present a detailed evaluation of the anthropometry and structural organization of the feto-placental vasculature in the chorionic plate, which is the main source for intra-cotyledon fetal blood flow.

Methods

Population

The study was conducted on 15 full-term placentas from donors who signed an informed consent form and who gave birth at 38–41 weeks of gestation. The study was approved by the hospital ethical committee. All the donors had normal pregnancies and delivered healthy newborn babies with weights ranging from 2700 kg to 3900 kg. The diameters of the umbilical arteries and vein at the cord insertion into the placenta were 2.3–5.51 mm and 3.4–8.78 mm, respectively.

Vascular corrosion casting

Cast models of the feto-placental vasculature were generated from full-term placentas by the corrosion casting technique similar to that used in previously published protocols (Arts, 1961; Habashi et al. 1983; Leiser et al. 1997; Mu et al. 2001). The placentas were treated within 5 min after delivery. The umbilical cord was trimmed about 5 cm from the insertion and the umbilical vessels were catheterized with 20–22 G intravascular catheters. The placental vascular bed was rinsed with a solution of saline and 5000 units mL−1 of heparin sulfate to drain all blood remains. We then squeezed the chorionic plate to remove all the saline from the chorionic vessels.

A low viscosity casting polymer from 4 g dental powder diluted with 20 mL liquid (Unifast Trad, GC Dental Co., Tokyo, Japan) was manually injected into the three umbilical vessels using separate syringes through the intravascular catheters. Different colored inks were added to the mixture for each umbilical vessel. The umbilical cord was held firmly upright to avoid spillage of the resin. The vessels were injected in series: first the narrowest artery, then the second artery, and then the vein. The rate of injection was low, about of 5 mL min−1, as in published protocols (Leiser et al. 1997). After injection the umbilical vessels were clamped. The placentas filled with the casting polymer were stored in the refrigerator for 4 days to allow the casting material to harden. Then the placentas with the hardened cast were immersed in a solution of 60% KOH and distilled water to erode the placental tissues surrounding the casts. A placenta cast model is shown in Fig. 1(a). We obtained rigid casts of the cotyledon vessels down to a diameter of 50 µm.

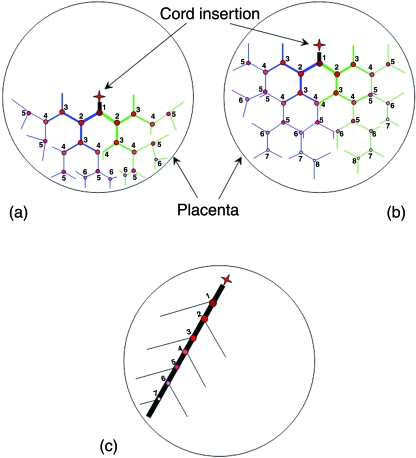

Fig. 1.

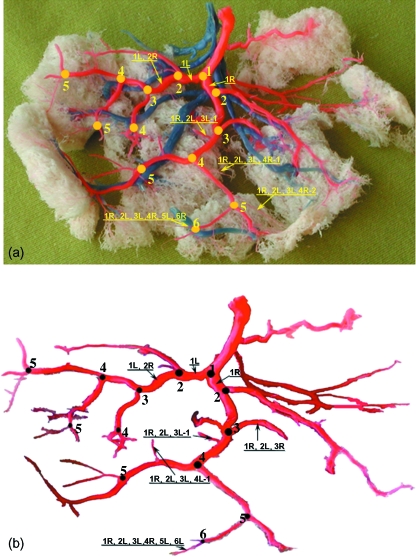

Mapping the branching network of the chorionic vasculature. (a) Identification of generation numbers and labels of branching vessels on a placental cast. The branching network is of one umbilical artery. The second artery had a much smaller network and is only partially visible in this figure. (b) Drawing of the arterial vasculature of the cast shown in (a) with vessel labels.

Data Analysis

Classification of the chorionic arterial network was performed using the definitions of dichotomous and monopodial branching patterns commonly used for evaluation of networks of blood vessels, pulmonary airways and botanic trees (Horsfield & Cumming, 1968; Parker et al. 1971; Zamir, 1976, 1988, 2001; Parker et al. 1997; Aharinejad et al. 1998; Kruszewski & Whitesides, 1998; Wang & Kraman, 2004). The dichotomous pattern defines a symmetric network of bifurcations in which each vessel branches into two fairly similar daughter vessels. The monopodial pattern defines a network of vessels in which a main, long mother tube courses for a long distance with an almost constant diameter, with small diameter daughter tubes branching off to the sides.

The location of each vessel within the chorionic network of vessels was assigned from the drawing of the full path from the umbilical cord insertion into the placenta to the vessel itself (Fig. 1). For the dichotomous pattern we identified a vessel by nR or nL, where n, R and L denote the generation number and whether it is the right or left daughter branch, respectively. Right and left branches correspond to the right and the left sides of the network with respect to the umbilical artery insertion, as shown in Fig. 1. The placental casts in this study showed that a monopodial pattern usually starts from a daughter tube of a dichotomous branch. Thus, we identified a monopodial branch, which is the m ramification off the nth right or left daughter vessel of a dichotomous branch, by nR-m or nL-m, respectively.

The branching pattern of the chorionic vasculature exhibits a combination of the dichotomous and monopodial patterns, as in other biological branching systems (e.g. pulmonary bronchi). Accordingly, we encoded each vessel by following the branching pattern beginning from the cord insertion. For example, encoding a branch by 1R,2L,3L,4L-1 (Fig. 1b) means (starting from the right end side or from the peripheral end on the chorionic plate) that it is the 1st monopodial branch of the left 4th generation which originates from the left 3rd branch of the left 2nd branch of the right 1st branch. We labeled all the chorionic vessels in this way (Fig. 1). The diameter of all the vessels was measured with a digital caliper with an accuracy of ± 10 µm. This data was used to compute the diameter ratio between the daughter (Dd) and the mother (Dm) vessels for further non-dimensional analysis of the anthropometry of the chorionic vessels.

Results

The polymeric casts of the fetal vasculature of full-term placentas provided information on the geometry of the umbilical, chorionic and IP vessels. In all the casts we observed the Hyrtl anastomosis, which connects the umbilical arteries within the placenta at a distance of 5 mm from the cord insertion. The umbilical arteries were injected in series with the different colored casting materials. Due to the presence of the Hyrtl anastomosis the colored polymer injected into the first umbilical artery also entered the second one and a mixture of the two colored materials was observed in the second umbilical artery.

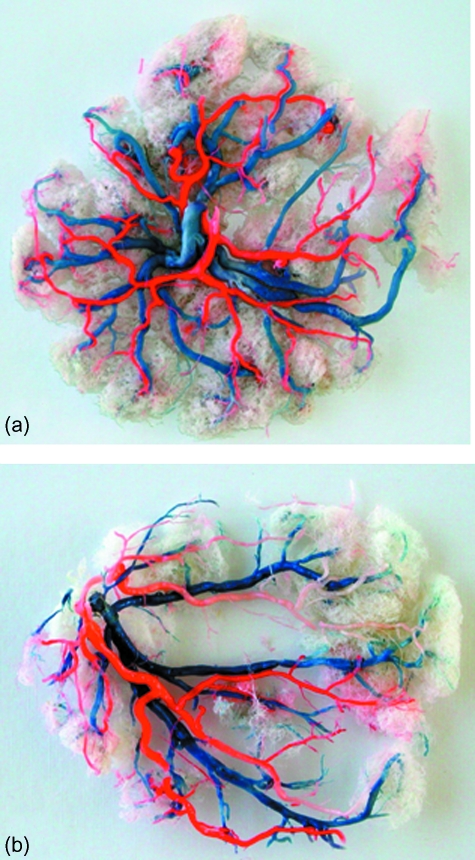

Observation of all 15 placental casts of this study does not reveal a pure dichotomous or monopodial branching pattern within the chorionic plate. However, in cases of central cord insertion (Fig. 2a), the blood vessels bifurcate mostly in a dichotomous pattern with a few monopodial ramifications from some dichotomous generations. In cases of marginal cord insertion (Fig. 2b), the first 1–3 generations bifurcate in a dichotomous pattern, whereas the rest of the bifurcations follow the monopodial pattern. In the centrally inserted cord the vessels that branch off the umbilical arteries traverse along half of the placenta diameter, whereas in a more peripheral insertion some branches traverse along two thirds of the diameter and others along only about one third of the chorionic plate diameter.

Fig. 2.

Placental casts. (a) Central cord insertion; both umbilical arteries were injected with red ink. (b) Marginal cord insertion; one artery was injected with white and the other with red ink.

The chorionic vessels branch through 6–8 generations from the cord insertion towards the margins of the chorionic plate. Measurements of the chorionic vessels showed that the first dichotomous bifurcation of the umbilical arteries was about 1 cm from the insertion, and the second one 2–4 cm from the insertion. The diameters of the first dichotomous arterial branches ranged from 1.13 to 5.36 mm, and those of the last dichotomous generations near the margins from 0.33 to 1.03 mm. The diameters of the first monopodial arterial branches were in the range 0.09–1.41 mm, and of the last monopodial generation 0.15–0.8 mm. The daughter-to-mother diameter ratio (Dd/Dm) for dichotomous bifurcations ranged from 0.6 to 0.8 with an angle of 70–100° between the daughter arteries. The daughter-to-mother diameter ratio of the ramifications in the monopodial pattern was 0.1–0.3, with the angle between ramifications and main branches ranging from 40° to 90°.

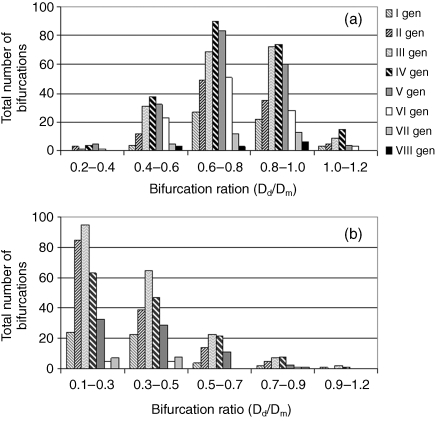

The total number of branches for each chorionic generation at several ranges of daughter-to-mother ratio was counted in all the placental casts. The total number of branches in each generation, the average daughter-to-mother ratio and standard deviation for each generation are summarized in Table 1. The distribution of arterial daughter-to-mother diameter ratios at each chorionic generation is presented by histograms for the dichotomous (Fig. 3a) and the monopodial (Fig. 3b) patterns. The vein bifurcated twice immediately after insertion into the placenta, creating four branches over a distance of less than 0.5 cm. The IP vessels entered the placenta at angles of 60–90º to the chorionic plate with diameters much smaller than those of the chorionic vessels, with a ratio of 0.16–0.77.

Table 1.

Total number of bifurcations, the average daughter-to-mother diameter ratio and standard deviation for each generation

| Dichotomous branches | Monopodial branches | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generation | No. of bifurcations | Average daughter-to-mother diameter ratio ± SD | No. of bifurcations | Average daughter-to-mother diameter ratio ± SD | No. of same branches in generation |

| I | 56 | 0.80 ± 0.14 | 54 | 0.35 ± 0.22 | 1-2 |

| II | 104 | 0.78 ± 0.17 | 143 | 0.31 ± 0.17 | 2-3-4-5 |

| III | 182 | 0.77 ± 0.18 | 192 | 0.34 ± 0.18 | 1-2-3 |

| IV | 220 | 0.76 ± 0.19 | 141 | 0.37 ± 0.19 | 1-2 |

| V | 184 | 0.73 ± 0.18 | 76 | 0.37 ± 0.16 | 0-1 |

| VI | 106 | 0.71 ± 0.16 | 11 | 0.35 ± 0.19 | 0 |

| VII | 30 | 0.76 ± 0.16 | 16 | 0.35 ± 0.17 | 0 |

| VIII | 12 | 0.76 ± 0.19 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Fig. 3.

Histograms of daughter-to-mother diameter ratios (Dd/Dm for given ranges) for each generation of the chorionic arteries: (a) dichotomous branching pattern; (b) monopodial branching pattern.

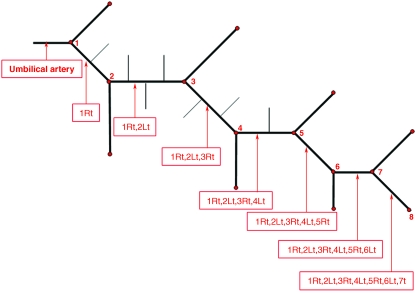

The data measured from all the placentas were used to evaluate a typical network for the chorionic arteries. Since the branching pattern is a mixture of dichotomous and monopodial patterns, we integrated the measured data from all the casts to propose the geometry for a typical network branching off an umbilical artery, as shown in Fig. 4. The data are summarized in Table 2.

Fig. 4.

Schematic description of a typical geometry for a network branching off an umbilical artery. The red points denote the generation number and the vessels are labeled.

Table 2.

Geometric data of the proposed typical network that branches off the umbilical artery (shown in Fig. 4)

| Segment label | Segment length (cm) | Segment diameter (mm) | No. of monopodial branches in segment | Diameter of monopodial branches in segment (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total covered length of the main trunk is 12 cm | ||||

| Umbilical artery | 1 | 4 | 0 | – |

| 1Rt | 2 | 3.2 | 1 | 0.56 |

| 1Rt,2Lt | 2 | 2.24 | 3 | 0.45 |

| 1Rt,2Lt,3Rt | 2 | 1.568 | 2 | 0.31 |

| 1Rt,2Lt,3Rt,4Lt | 2 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.2 |

| 1Rt,2Lt,3Rt,4Lt,5Rt | 2 | 0.77 | 0 | – |

| 1Rt,2Lt,3Rt,4Lt,5Rt,6Lt | 1.5 | 0.62 | 0 | – |

| 1Rt,2Lt,3Rt,4Lt,5Rt,6Lt,7Rt | 1.5 | 0.55 | 0 | – |

Discussion

The structural organization of the chorionic vasculature was analyzed from cast models of full-term placentas. The models were generated by the corrosion technique using a dental polymer mixture. The low viscosity of the polymer mixture enabled manual filling of the blood vessels, including the capillary region. The polymer mixture was colored differently for the arteries and vein to distinguish between their branches. The resulting cast models revealed the capillary system stemming from the IP vessels, which penetrate into the placenta from the chorionic plate. These capillary trees were similar to structures obtained by other techniques (Kaufmann et al. 1985), which implies that our casting technique was reliable. In some placentas we observed gaps within the chorionic plate without cotyledons, which may exist due to infarcted regions or degenerated areas with no blood vessel.

The cast models of this study demonstrated very well the Hyrtl anastomosis between the umbilical arteries in the vicinity of the umbilical cord insertion into the placenta (Arts, 1961; Raio et al. 1999, 2001; Ullberg et al. 2001). During filling of the placental vasculature with the casting polymer we injected different colored inks into each of the umbilical arteries. The first branches of the second artery revealed a mixture of the two colors due to passing of the casting material via the Hyrtl anastomosis while injecting the first artery.

The daughter-to-mother diameter ratio of the dichotomous and monopodial branching patterns reflects their different role in the distribution of fetal blood over the chorionic plate (Fig. 3). The distribution of the daughter-to-mother diameter ratio of the dichotomous network has a bell shape with a maximum in the range of 0.6–0.8 up to the 7th generations (Fig. 3a). Peripheral blood vessels have a diameter of about 1.2 mm and the daughter-to-mother diameter ratio increases to 0.8–1.0 as a smaller ratio may increase the resistance to blood flow. In the monopodial network (Fig. 3b), the daughter-to-mother diameter ratio is in the range of 0.1–0.3 up to the 6th generations as reported for the mouse bronchial tree (Onuma et al. 2001) because the diameter of the main vessel was fairly constant all the way to the periphery. For generation 6 and 7 the daughter-to-mother ratio is larger, with a maximum in the range 0.3–0.5.

Examination of all the placental casts provided additional evidence that the architecture of the chorionic vasculature is not purely dichotomous or monopodial. The placental casts demonstrated that umbilical cord insertion was located anywhere between the center and the margins of the placenta. For a central insertion the dichotomous pattern was dominant, whereas for a marginal insertion the monopodial pattern was dominant. In the more frequent cases of cord insertion neither in the center nor in the margin, the branching structure was a mixture of dichotomous and monopodial patterns. These results support previous observations that the network of chorionic blood vessels represents a mixture of disperse and magistral branching patterns (Benirschke & Kaufmann, 1995). In the present study we prefer the more accurate terminology of ‘dichotomous’ and ‘monopodial’ branching patterns.

Classification of vasculature branching networks is well established in the literature, especially in organs like the coronary arteries of the human heart, which were sorted into two groups (Aharinejad et al. 1998). The first group is composed of ‘distributing’ vessels, which run along the heart borders and convey blood to major zones. The second group is composed of the ‘delivering’ vessels that branch off from the distributing vessels and enter into every zone of the myocardium to deliver blood at sufficient low velocities that permit gas and nutrition exchange. This difference is significant in hemodynamic assessment of the importance of these vessels in a particular heart. More recently, it was proposed that repeatedly symmetrical bifurcating vascular structures with a high daughter-to-mother diameter ratio (i.e. dichotomous) can be classified as delivering vessel trees, whereas highly asymmetric structures with small daughter-to-mother diameter ratios (i.e. monopodial) can be classified as conveying, or distributing, vessels (Aharinejad et al. 1998).

A similar architecture exists in the placenta where the chorionic blood vessels convey blood from the umbilical cord across the whole chorionic surface of the placenta to perfuse blood into the whole volume of the placenta. However, the requirement for homogeneous blood supply to all regions of the chorionic plate to ensure efficient exchange of metabolic products within all the cotyledons dictates the anthropometry of the chorionic vasculature, depending on the location of the cord insertion. Thus, the pattern is not like that of the conveying (or distributing) vessels on the heart border, but a combination of both conveying and delivering vessels. In a marginal cord insertion, the distance to the opposite margin may be as large as the placental diameter. In this case, the most efficient way to supply blood would be a monopodial branching pattern in which the diameter of the main conducting vessel is almost constant, with minimal variation in the resistance to blood flow. However, in a pure monopodial pattern a relatively large area perpendicular to the main trunk will not be adequately perfused. Thus, the first 2–3 generations of the umbilical arteries branch in a dichotomous pattern and then follow a more monopodial pattern. This may also explain the gaps in our casts where insertion is very marginal (Fig. 2b). In case of a central cord insertion, the distance to the chorionic plate margin is only one half of the placenta diameter and a dichotomous branching pattern may be the easiest way to traverse most of the chorionic plate with a minimal number of generations. A few monopodial ramifications coming off the first and second dichotomous branches ensure perfusion of the areas in between. It should be noted that Benirschke & Kaufmann (1995) were aware of the fact that the organization of the chorionic vasculature is consistent, not random, and dependent on the umbilical cord insertion, but they could not explain the physiological reasons.

The structural organization of the chorionic vessels evolved for efficient perfusion of the chorionic plate. If each of the umbilical arteries branched in a pure dichotomous pattern over the chorionic plate, then the pattern would take the forms shown in Fig. 5(a,b) for central and marginal insertions. For a central insertion about 4–6 generations will be needed to reach the placenta margins, whereas 5–8 generations will do it for a marginal insertion. Based on the daughter-to-mother ratio and assuming the umbilical artery has a 4 mm diameter at the insertion, the diameter of the peripheral vessels would be 0.48 mm and 0.23 mm for the central and marginal insertions, respectively. These vessels have a small diameter with a large blood flow resistance compared to the resistance in the large chorionic vessels, which may affect blood perfusion to the placenta margins. Moreover, the peripheral branches of such a pure dichotomous network would collide with each other. Alternatively, if a pure monopodial network traversed from a marginally inserted umbilical artery, a great percentage of the area perpendicular to the main trunk would be left out (Fig. 5c). Thus, homogeneous perfusion of the chorionic plate requires a branching structure that combines dichotomous and monopodial patterns.

Fig. 5.

Schematic description of hypothetic organizations for the chorionic plate vessels. (a) Pure dichotomous branching pattern for a central insertion. (b) Pure dichotomous branching pattern for a marginal insertion. (c) Pure monopodial branching pattern for a marginal insertion.

Placental development and feto-placental angiogenesis are critical for successful gestation and have been studied comprehensively in relation to fetal pathologies such as pre-eclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and abruption (Chaddha et al. 2004). It is well established that feto-placental circulation becomes functional, with a closed loop of blood circulation, when the fetal heart starts to beat at about 5.5 weeks of gestation (Salafia & Maas, 2005). There is also strong evidence that the vasculature of the chorionic plate is functionally established by 12 weeks of gestation (Boyd & Hamilton, 1970). It is generally agreed that the normal placenta shape at term is ovoid with cord insertion near the disk center, but it is unclear how and why an asymmetric placenta with a marginal cord insertion is developed. However, there is evidence that it is related to early compensation due to abnormal intrauterine oxygen gradients and nutrient availability, which induce placental regression from what was supposed to be a normal placenta with a central cord insertion (Jauniaux et al. 2003; Chaddha et al. 2004; Salafia & Maas, 2005).

The chorionic plate vessels constitute the ‘high-capacity low-resistance’ of the feto-placental vasculature that link the umbilical vessels to the actual sites of oxygen and nutrient exchange in the placental villi. Since the feto-placental vasculature takes up to 50% of fetal blood volume (Adamson, 1999; Salafia & Maas, 2005), the function of the chorionic plate vessels is crucial in fetal development. Many studies were conducted to explore the role of angiogenic growth factors in the process of placental morphogenesis and their correlation with pregnancy-related fetal diseases (Charnock-Jones & Burton, 2000; Regnault et al. 2002; Torry et al. 2004). Some clinical studies revealed marginal insertion of the umbilical cord in about 42% cases of pregnancy-induced hypertension (Pretorius et al. 1996) and a correlation with low birthweight babies (Rath et al. 2000). It was also observed that the mean number of infarcted areas and marginal insertion of umbilical cord was significantly higher in the mother hypertensive group in comparison with a control group (Majumdar et al. 2005).

Previously, we used the anthropometric data of this study in a computational analysis of fetal blood perfusion in models of basic branching units in the chorionic vasculature (Gordon et al. 2007). The hemodynamic analysis demonstrated that energy losses due to pressure gradients in the bifurcation region are smaller in the monopodial branching model than in the dichotomous model. This supports the fact that the monopodial pattern is more efficient for delivering blood long distances, whereas the dichotomous pattern is efficient for perfusing large areas. We propose that the natural development of dichotomous branches in a marginal insertion will not be able to perfuse the far end of the chorionic plate. Thus, nature modifies the dichotomous pattern into a monopodial one to compensate for the hypothetically missing blood flow at the opposing periphery. This hypothesis requires further investigation of placental vasculature development during the early weeks of pregnancy.

The anthropometric data obtained from the 15 placental casts of this study were used to generate a typical architecture for the network of vessels that branch off the umbilical artery (Fig. 4). This typical geometry may be used for models of the vasculature for experimental or computational investigations of chorionic blood perfusion. The length of each generation was estimated to allow for the network to traverse the chorionic surface from cord insertion to placental perimeter. We assumed an average diameter of 200 mm to represent a typical healthy placenta. This model will allow development of additional studies of the efficacy of each network unit to provide homogeneous blood perfusion over the chorionic plate. In addition, the branching ratios comply with published data for monopodial and dichotomous branching segments (Onuma et al. 2001; Wang & Kraman, 2004).

In conclusion, the anthropometry and branching architecture of the chorionic vessels of the human placenta were investigated. Observations of cast models of full-term placentas revealed that the branching architecture of the chorionic vessels is a combination of dichotomous and monopodial patterns, where the first 2–3 generations are always of a dichotomous nature. Analysis of the daughter-to-mother diameter ratios in the chorionic vessels provided a maximum in the range of 0.6–0.8 for the dichotomous branches, whereas in monopodial branches the maximum was in the range of 0.1–0.3. Similar to previous studies, this study reveals that the vasculature architecture was mostly monopodial for the marginal cord insertion and mostly dichotomous for the central insertion. The more marginal the umbilical cord insertion on the chorionic plate, the more monopodial branching patterns are created to perfuse distant placental territories.

References

- Adamson SL. Arterial pressure, vascular input impedance and resistance as determinants of pulsatile blood flow in the umbilical artery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1999;84:119–125. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(98)00320-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aharinejad S, Schreiner W, Neumann F. Morphometry of human coronary arterial trees. Anat Rec. 1998;251:50–59. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199805)251:1<50::AID-AR9>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arts NFT. Investigations on the vascular system of the placenta. Part I. General introduction and the fetal vascular system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1961;82:147–158. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)36109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benirschke K, Kaufmann P. Pathology of the Human Placenta. New York: Springer; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd JD, Hamilton WJ. The Human Placenta. Cambridge: W Heffer and Sons; 1970. Chapters 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Burton GJ. The fine structure of the human placental villous as revealed by scanning electron microscopy. Scanning Microscopy. 1987;1:1811–1828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellucci M, Scheper M, Scheffen I, Celona A, Kaufmann P. The development of the human placental villous tree. Anat Embryol. 1990;181:117–128. doi: 10.1007/BF00198951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaddha V, Viero S, Huppertz B, Kingdom J. Developmental biology of the placenta and the origins of placental insufficiency. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2004;9:357–369. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charnock-Jones DS, Burton GJ. Placental vascular morphogenesis. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;14:953–968. doi: 10.1053/beog.2000.0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Paepe ME, Burke S, Luks FI, Pinar H, Singer DB. Demonstration of placental vascular anatomy in monochorionic twin gestations. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2002;5:37–44. doi: 10.1007/s10024-001-0089-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir R, Kosanke G, Kohnen G, Kertschanska S, Kaufmann P. Classification of human placental stem villi: review of structural and functional aspects. Microsc Res Tech. 1997;38:29–41. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19970701/15)38:1/2<29::AID-JEMT5>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon Z, Elad D, Jaffa AJ, Eytan O. Fetal blood flow in branching models of the chorionic arterial vasculature. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1101:250–265. doi: 10.1196/annals.1389.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habashi S, Burton GJ, Steven DH. Morphological study of the fetal vasculature of the human term placenta: scanning electron microscopy of corrosion casts. Placenta. 1983;4:41–56. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(83)80016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsfield K, Cumming G. Morphology of the bronchial tree in man. J Appl Physiol. 1968;24:373–383. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1968.24.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jauniaux E, Hempstock J, Greenwold N, Burton GJ. Trophoblastic oxidative stress in relation to temporal and regional differences in maternal placental blood flow in normal and abnormal early pregnancies. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:115–125. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63803-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann P, Bruns U, Leiser R, Luckhardt M, Winterhager E. The fetal vascularisation of term human placental villi. II. Intermediate and terminal villi. Anat Embryol. 1985;173:203–214. doi: 10.1007/BF00316301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingdom JCP, Burrell SJ, Kaufmann P. Pathology and clinical implications of abnormal umbilical artery Doppler waveforms. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1997;9:271–286. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1997.09040271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkinen P, Kurmanavichius J, Huch A, Huch R. Blood flow velocities in human intraplacental arteries. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1994;73:220–224. doi: 10.3109/00016349409023443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishore N, Sarkar SC. The arterial patterns of placenta. A postpartum radiological study. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 1967;17:9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kruszewski P, Whitesides S. A general random combinatorial model of botanical trees. J Theor Biol. 1998;191:221–236. [Google Scholar]

- Lee MML, Yeh M. Fetal circulation of the placenta: a comparative study of human and baboon placenta by scanning electron microscopy of vascular casts. Placenta. 1983;4:515–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MML, Yeh M. Fetal microcirculation of abnormal human placenta. I. Scanning electron microscopy of placental vascular casts from small for gestational age fetus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;154:1133–1139. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(86)90774-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiser R, Krebs C, Ebert B, Dantzer V. Placental vascular corrosion cast studies: a comparison between ruminants and humans. Microsc Res Tech. 1997;38:76–87. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19970701/15)38:1/2<76::AID-JEMT9>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiser R, Luckhardt M, Kaufmann P, Winterhager E, Bruns U. The fetal vascularisation of term human placental villi. I. Peripheral stem villi. Anat Embryol. 1985;173:71–80. doi: 10.1007/BF00707305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar S, Dasgupta H, Bhattacharya K, Bhattacharya A. A study of placenta in normal and hypertensive pregnancies. J Anat Soc India. 2005;54:34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mine M, Nishio J, Nakai Y, Imanaka M, Ogita S. Effects of umbilical arterial resistance on its arterial blood flow velocity waveforms. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu J, Kanzaki T, Tomimatsu T, Fukada H, Fujii E, Fuke S, et al. A comparative study of intraplacental villous arteries by latex cast model in vitro and color Doppler flow imaging in vivo. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2001;27:297–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2001.tb01273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onuma K, Ebina M, Takahashi T, Nukiwa T. Irregularity of airway branching in a mouse bronchial tree: a 3-D morphometric study. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2001;194:157–164. doi: 10.1620/tjem.194.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker H, Horsfield K, Cumming G. Morphology of distal airways in the human lung. J Appl Physiol. 1971;31:386–391. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1971.31.3.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JC, Cave CB, Ardell JL, Hamm CR, Williams SG. Vascular tree structure affects lung blood flow heterogeneity simulated in three dimensions. J Appl Physiol. 1997;83:1370–1382. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.4.1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pretorius DH, Chau C, Poeltler DM, Mendoza A, Catanzarite VA, Hollenbach KA. Placental cord insertion visualization with prenatal ultrasonography. J Ultrasound Med. 1996;15:585–593. doi: 10.7863/jum.1996.15.8.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pretorius DH, Nelson TR, Baergen RN, Pai E, Cantrell C. Imaging of placental vasculature using three-dimensional ultrasound and color power Doppler: a preliminary study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1998;12:45–49. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1998.12010045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raio L, Ghezzi F, Di Naro E, Franchi M, Balestreri D, Dürig P, et al. In-utero characterization of the blood flow in the Hyrtl anastomosis. Placenta. 2001;22:597–601. doi: 10.1053/plac.2001.0685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raio L, Ghezzi F, Di Naro E, Franchi M, Brühwiler H. Prenatal assessment of the Hyrtl anastomosis and evaluation of its function: case report. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:1890–1893. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.7.1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rath G, Garg K, Sood M. Insertion of umbilical cord on the placenta in hypertensive mother. J Anat Soc India. 2000;49:149–152. [Google Scholar]

- Regnault TR, Galan HL, Parker TA, Anthony RV. Placental development in normal and compromised pregnancies – a review. Placenta. 2002;23(Suppl.):119–129. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salafia CM, Maas E. The twin placenta: framework for gross analysis in fetal origins of adult disease initiatives. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2005;19(Suppl):23–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2005.00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torry DS, Hinrichs M, Torry RJ. Determinants of placental vascularity. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2004;51:257–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2004.00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullberg U, Sandstedt B, Lingman G. Hyrtl's anastomosis, the only connection between the two umbilical arteries. A study in full term placentas from AGA infants with normal umbilical artery blood flow. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:1–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2001.800101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PM, Kraman SS. Fractal branching pattern of the monopodial canine airway. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:2194–2199. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00604.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagel S, Anteby EY, Shen O, Cohen SM, Friedman Z, Achiron R. Placental blood flow measured by simultaneous multigate spectral Doppler imaging in pregnancies complicated by placental vascular abnormalities. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1999a;14:262–266. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1999.14040262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagel S, Anteby EY, Shen O, Cohen SM, Friedman Z, Achiron R. Simultaneous multigate spectral Doppler imaging of the umbilical artery and placental vessels: novel ultrasound technology. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1999b;14:256–261. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1999.14040256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamir M. The role of shear forces in arterial branching. J Gen Physiol. 1976;67:213–222. doi: 10.1085/jgp.67.2.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamir M. Distributing and delivering vessels of the human heart. J Gen Physiol. 1988;91:725–735. doi: 10.1085/jgp.91.5.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamir M. Fractal dimensions and multifractility in vascular branching. J Theor Biol. 2001;212:183–190. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2001.2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]