Abstract

Objective

Many children with asthma do not take medications as prescribed. We studied parents of children with asthma to define patterns of non-concordance between families’ use of asthma controller medications and clinicians’ recommendations, examine parents’ explanatory models (EM) of asthma, and describe relationships between patterns of non-concordance and EM.

Methods

Qualitative study using semi-structured interviews with parents of children with persistent asthma. Grounded theory analysis identified recurrent themes and relationships between reported medication use, EMs, and other factors.

Results

Twelve of the 37 parents reported non-concordance with providers’ recommendations. Three types of non-concordance were identified: unintentional – parents believed they were following recommendations; unplanned – parents reported intending to give controller medications but could not; and intentional – parents stated giving medication was the wrong course of action. Analysis revealed two EMs of asthma: chronic – parents believed their child always has asthma; and intermittent – parents believed asthma was a problem their child sometimes developed.

Conclusions

Concordance or non-concordance with recommended use of medications were related to EM’s and family context and took on three different patterns associated with medication underuse.

Practice Implications

Efforts to reduce medication underuse in children with asthma may be optimized by identifying different types of non-concordance and tailoring interventions accordingly.

Keywords: asthma, adherence, concordance, qualitative methods, explanatory models

1. Introduction

Although strong evidence shows that daily controller medications prevent adverse outcomes and improve functional status in children with asthma,1, 2 many children do not use them daily as recommended. 3–8 Studies of children with asthma have commonly found rates of adherence with medication regimens of 50% or worse. 9, 10 Lower levels of asthma knowledge, family dysfunction, limited access to medications, low treatment expectations, and negative attitudes toward inhaled controller medications have been associated with poor adherence.11, 12, 13, 14, 15 Yet effective interventions to improve adherence remain elusive. A more thorough understanding of the patterns of controller medication underuse is needed to help clinicians develop the most effective strategies for addressing this highly complex problem.

Parents’ decisions about managing their children’s asthma may be guided by their explanatory models (EMs) of asthma.16 EMs include perceptions of etiology, time and onset of symptoms, pathophysiology, course of illness (including severity and chronicity), and treatment. EMs integrate personal beliefs, cultural norms, and past experience. Prior work examining parents’ explanatory models of asthma has broadened our understanding of how parents conceptualize asthma. These studies have shown that families rely on their cultural and environmental contexts to understand asthma and have described differences between explanatory models of patients and providers, indicating the need for providers to explore explanatory models with parents in the clinical encounter.17–19 However, these studies do not show how EMs relate to decisions about asthma management in the context of daily life.

Our study was designed to understand relationship between EMs and concordance regarding medication use among children with asthma. We use the concept of concordance,20, 21 departing from “adherence” or “compliance”, the terms typically used when comparing actual behavior against an objective standard (e.g. medication doses taken compared with those prescribed). Concordance reflects the match between provider recommendations and “contrasted but equally cogent” 22 parental beliefs and behaviors regarding giving medications. Many studies on adherence in chronic illness label patients as either ‘adherent’ or ‘non-adherent.’23 Whereas a few studies discuss reasons for non-adherence in child asthma, no empirical work to date has explicitly distinguished between types of non-adherence.

Through the use of qualitative interviews, we sought to explore patterns of parents’ reported behaviors regarding giving children medication, and how these behaviors were interconnected with EMs and other features of family life. Our aims were to (1) define and describe patterns of concordance or non-concordance between families’ use of medications and clinicians’ recommendations; (2) examine parents’ EMs of asthma; and (3) describe patterns amongst concordance or non-concordance, EMs and other contextual factors.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and recruitment

Participants were a purposive sample of African-American, Latino and white parents of children aged 5 to 12 years with persistent asthma. The sampling frame was theoretically driven by 1) previous work24 indicating differences in adherence among minority children and 2) theoretical work indicating that explanatory models and patient-provider communication may vary culturally 16. Parents were recruited from three socio-economically and ethnically diverse sites in the Boston area: an inner-city academic medical center, a neighborhood health center, and a multi-specialty clinician group. Patients had either Medicaid covering prescriptions in full, or private insurance with prescription co-payments of $5 to $25. The institutional review board at each site approved the study.

Potentially eligible families were identified via computerized data on the child’s outpatient and pharmacy claims for asthma and then sent letters describing the study. Eligible caregivers had primary responsibility for the child’s medical care, self-identified as African-American, Latino, or White, and brought the child for an outpatient visit for an asthma exacerbation, sick visit, asthma maintenance or well-child visit during the study period. Eligible children had persistent asthma in the last year based on either computerized data that met Health Employer Data Information Set criteria – one inpatient or emergency department visit or 4 medication dispensing events, or 4 outpatient asthma visits and at least 2 asthma medication dispensing events – or a parent report of symptom frequency that met National Asthma Education and Prevention Program criteria in response to structured questions.25, 26 The study was conducted over one year excluding summer when asthma flares are least common.

For the present analysis we included only patients who were prescribed controller medications, defined as inhaled anti-inflammatories, inhaled cromones, and oral leukotriene modifiers. A research assistant worked with clinic staff to identify eligible patients with appointments then approached potentially eligible parents in the clinic waiting area to invite participation, administer eligibility screening and demographic questions and obtain written informed consent. Participants were given a $10 gift card for their initial participation. Participants’ clinical encounters were audiotaped via a recorder set up in the exam room. Participants were later contacted by an investigator to schedule a follow-up interview within two weeks of the clinical encounter.

Each parent interview was conducted in English or Spanish by an experienced qualitative investigator of the same race/ethnicity as the parent. Parents were given a $50 incentive. Interviews occurred in the family’s home, at the site of health care, or another mutually agreed-upon location. During the 1 ½ hour semi-structured interview parents were asked to describe their family, a typical day, experiences living with a child with asthma, their knowledge about asthma, what they thought caused asthma, the severity of their child’s asthma, their concerns about asthma, their last appointment with their clinician, and the medications and strategies they used to manage their child’s asthma.

Interviewers wrote field notes after each interview to document observations about the physical and social aspects of the home or medical setting, neighborhood and community. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and transcriptions were reviewed by a study investigator for accuracy.

After each interview was conducted, we reviewed the audiotape of the clinical interaction and the medical record to identify what medications were prescribed and how the clinician recommended they be taken. Information from the recording was privileged in cases of disagreement between the two sources of information. Concordance was assessed by comparing parents’ reports of the ways in which they gave their children medication with providers’ medication recommendations. We operationally defined the term “concordance” as agreement between clinician recommendations and parents’ reported medication-giving behaviors. We assessed reported frequency of administration, but not dosage, of specified medications, as parents rarely discussed dosage in their interviews.

2.2. Analysis

Qualitative analyses were conducted by five investigators using methods of thematic analysis with a grounded theory structure 27. Initially, three transcripts were jointly coded using open coding strategies to develop a coding dictionary to reflect emergent themes and content revealed in the interviews. Consistent with the tenets of grounded theory methodology, after an initial set of interviews was completed, we refined the interview protocol to address parents’ perceptions of asthma predictability. Individual investigators coded subsets of transcripts, and codes underwent revision in biweekly meetings until a total of 47 separate codes were identified, capturing themes related to the impact of asthma on activities and family quality of life; the experiences of parenting a child with asthma; roles and strategies related to asthma management; beliefs, knowledge and actions related to medications; EMs, severity and predictability; and perspectives on clinicians. Axial coding, involving sorting and classifying of selected codes, resulted in the identification of three primary domains related to medication use and related factors: (1) parents’ reported use of medication, (2) competing priorities, and (3) family routines. In addition, three aspects of EMs were identified: (1) beliefs about the chronicity of asthma, (2) perceptions of severity, and (3) perceptions of predictability. The five investigators jointly conducted constant comparison analysis, examining sections of transcripts for subtle differences in language used to describe asthma and medication use.Investigators conceptualized and agreed upon recurrent themes in the data to identify patterns of explanatory models, parent perceptions of severity and predictability, contextual factors and reported medication-giving behavior. Using Nvivo 28 qualitative analysis software, matrices were developed that included qualitative coding regarding medication use and explanatory models, and demographic information.

Concordance was determined by comparing the medications identified as prescribed from the audio recording and/or medical record and the report given by the parent. Two investigators reviewed each transcript to determine concordance type and explanatory model; disagreements were resolved through discussion by the entire team.

3. Results

We approached 128 parents; 54 participated in audio-taping of clinical encounters, and 44 of these participated in interviews. Among the non-participants, seven declined to participate, 64 were ineligible based on screening criteria, and three had the consent process interrupted and could not participate. Of the 44 who participated in interviews, seven were excluded from analysis because the child had not been prescribed a controller medication, leaving 37 parent interviews for the current analysis. Among these parents, 17 were African-American, 13 were white, and seven were Latino. Six interviews were conducted in Spanish, the rest in English. The reason for the clinical encounter, medications prescribed, participant demographics, and frequency of symptoms based on National Asthma Education and Prevention Program criteria for persistence of asthma are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and asthma severity of participants n=37

| Child age | Mean 7.7 years |

|---|---|

| Insurance status | |

| Public | 15(41%) |

| Private | 18(49%) |

| Unknown | 4 (11%) |

| Parent race/ethnicity | |

| White | 13(35%) |

| African-American | 17 (46%) |

| Latino | 7 (19%) |

| Parent education | |

| <High school | 4 (11%) |

| High school graduate | 9 (24%) |

| Some college | 8 (22%) |

| College degree or higher | 7 (19%) |

| Unknown | 9 (24%) |

| Family income (yearly) | |

| <$20,000 | 11(30%) |

| $21,000<$40,000 | 5 (14%) |

| $41,000<$80,000 | 4 (11%) |

| >$80,000 | 4 (11%) |

| Unknown | 13(35%) |

| Reason for visit | |

| Asthma flare | 16 (43%) |

| Well-child visit | 11(30%) |

| Asthma follow-up | 3 (8%) |

| Non-asthma specific sick visit | 7 (19%) |

| Asthma severity* | |

| 1. Days with wheezing, chest tightness, cough, or shortness of breath: | |

| ≤ 4 days | 25 (68%) |

| ≥ 4 days | 12 (32%) |

| 2. Days child had to slow down or stop his/her play or activities because of asthma, wheezing, chest tightness, cough, or shortness of breath? | |

| ≤ 4 days | 31 (84%) |

| ≥ 4 days | 6 (16%) |

| 3. Nights child woke up because of asthma, wheezing, chest tightness, cough, or shortness of breath? | |

| ≤ 2days | 26 (72%) |

| ≥ 3 days | 11 (28%) |

| Controller medications prescribed # | |

| Inhaled corticosteroids (Flovent, Pulmicort) | 33 |

| Inhaled cromones | 2 |

| Oral montelukast (Leukotrine modifier) | 3 |

During the last 2 weeks (if not currently symptomatic), or during the 2 weeks before the current flare began (if currently symptomatic), based on criteria for persistent asthma from the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program.

A child may have more than one controller medication prescribed.

3.1. Reported medication-giving behaviors

We identified four patterns of concordance or non-concordance reported by parents in the interviews: 1) concordance, 2) unintentional non-concordance, 3) unplanned non-concordance and 4) intentional non-concordance. In both concordance and unintentional non-concordance, parents believed they were giving medications as prescribed by the clinician. In unplanned and intentional non-concordance, parents understood they were not giving the medications as prescribed by the clinician. We describe each of these patterns and provide examples in Table 2.

Table 2.

Examples of Types of Concordance: Examples are meant to provide a flavor of the types of concordance although actual determination of concordance relied on the evaluation of the entire interview transcript.

| Medication giving behavior | Example |

|---|---|

| Concordance | PAR: And then sure enough, she had a flare up and she went way back, and way over the amount that she was on initially. And then, since then she's had a couple of medications added. And she's never come off completely. When she has a flare up, she ends up having to go way up on inhaled and then occasionally go on to oral steroids as well. So she's never come off. |

| Unintentional Non-concordance | PAR: Yes. She gave me a couple things. She gave me, I think Prednisone he was supposed to take for three days. And there was another one he was supposed to take for six days. I’ve forgotten was that was, the Prednisone remember. There was something else. |

| INT: So she gave you those two medications. Did she give you anything else to use on a daily basis with him? | |

| PAR: She gave me some chewables, chewable something. That he takes once a day. | |

| INT: Every day? | |

| PAR: I think it was like for a couple of weeks. I’ve forgotten what those were – they were chewable. It’s not Prednisone, because he was supposed to take that with the Prednisone he was taking I can’t remember what that was. | |

| INT: That’s all right. So three things she gave you. Some of them only though were to take for a few days, and one for a few weeks. | |

| PAR: I think six days. Six days | |

| … | |

| : PAR: Well, [asthma] might have been explained sufficiently, but I don’t think I’ve grasped a total understanding of it that maybe I should have. | |

| Unplanned non-concordance | PAR: Um, I just make -- try to make sure I do it before I leave. |

| INT: In the morning. | |

| PAR: Because sometimes I do forget, but – | |

| INT: Right. | |

| PAR: -- just before -- make sure I do it in the morning. | |

| INT: OK. And you’re the only one who gives it to her? | |

| PAR: Unless she stays the night with my mom or something. Then I send it with her. | |

| … | |

| PAR: I probably would not give it to her if like I forget it, it’s like, like I said, if she stays the night somewhere I might forget to send it, but it doesn’t worry that much if I forget the, um, Flovent. | |

| INT: OK. | |

| PAR: I know it helps in the long run, and all of that, but it doesn’t really seem like it’s that serious as far as the Albuterol, if she needs it or whatever. | |

| INT: Right. OK. | |

| PAR: So it’s not really like -- like, if she’s kind of sick, or if I think she’s going to get sick, then I send the Albuterol with her, to where she’s going. If I don’t send the Flovent, I’m not -- I don’t really get too concerned, like, oh, I’m leaving it at home. | |

| Intentional non-concordance: | PAR: He is on his - he is on Cromolyn, which because he has been doing so well, I haven’t been giving it to him on a daily basis.…I do like whenever he starts to come down with a cold. You know, if he has the sniffles, then I will start him. I will say okay, you should definitely be on your medication.… When I think that he is well enough to be taken off of the medication then I do. |

| PAR: But see, I don’t have a problem stopping it myself. Do you know what? I am using my own instincts. | |

| INT: To stop taking the medications. | |

| PAR: Sure. I didn#x02019;t give it to him today. And I could have given it to him today. And I was aware that I was - should I, shouldn’t I? | |

| INT: So you thought about not giving the medication to him? | |

| PAR: Right. And I figured I would stop it when I thought the time was right. | |

| INT: So you decided not to give it to him today. | |

| PAR: Today. | |

Transcription conventions:

PAR = parent

INT= interviewer

Ellipses (…):transcript text not included

Dashes ( --): hesitation by speaker

3.1.1. Concordance

Twenty-five of the 37 parents described concordance – using controller medication the way the clinician recommended. This meant that parents were giving their child controller medication daily year round, or in some cases seasonally, to prevent the onset of asthma symptoms. Concordance only referred to daily use of controller medications not accuracy of dosage. For children with seasonal asthma, once controller medication was initiated after a first seasonal flare-up, parents continued to administer medications daily. Concordance with clinician recommendations was reported by 11 of the 13 white parents, 4 of the 7 Latino parents, and 10 of the 17 African-American parents.

3.1.2. Unintentional non-concordance

Two of the 37 parents described unintentional non-concordance – they reported following the clinician’s recommendation, but their description differed from the clinician's instructions given during the audiotaped visit and documented in the medical record. Unintentional non-concordance was reported by 1 of the 17 African-American parents, and 1 of the 7 Latino parents.

3.1.3. Unplanned non-concordance

Five of the 37 parents described unplanned non-concordance. These parents reported that although they intended to give controller medications daily as directed, they were unable to do so. These parents described contextual barriers in their daily lives to giving medications as prescribed. Unplanned non-concordance was reported by 2 of the 13 white parents, 2 of the 17 African-American parents, and 1 of the 7 Latino parents.

Intentional non-concordance

Five of the 37 parents stated that they intentionally did not give their child controller medications as recommended. These parents explicitly told the interviewer that they believed that giving their child the medication was the wrong course of action, and therefore did not follow the recommendations of the clinician. One of the 13 white parents, 3 of the 17 African-American parents, and 1 of the 7 Latino parents reported intentional non-concordance. Only one parent stated that she told her provider about her decision not to give controller medications.

3.2 Explanatory models

We coded interviews for three aspects of explanatory models: (1) the course of asthma, (2) the predictability of asthma symptoms, and (3) perceptions of severity. We then examined the relationship between these and concordance or non-concordance with medication recommendations.

3.2.1. Explanatory models – course of asthma

We identified two predominant ways parents explained the course of asthma: 1) a chronic explanatory model in which parents believed their children always has asthma, which is triggered sometimes; and 2) an intermittent explanatory model in which parents believed asthma was something that their children contracted temporarily, but did not always have. Determination of which EM a parent expressed depended on the evaluation of the entire transcript. Brief examples are provided below.

Cultural differences in beliefs, practices or EM did not emerge in any systematic way in our analyses. We found no differences in EMs according to race/ethnicity, insurance status (as a proxy for socioeconomic status), or parent educational level. Other themes related to EM emerged in the analysis but is beyond the scope of the current paper.

3.2.2. The chronic explanatory model

Twenty-one of the 37 parents described their child’s asthma using a chronic EM. This model was close to the biomedical model of asthma typically held by clinicians 26. In this model, parents understood asthma as something that children had all the time, regardless of whether they were actively symptomatic. They explained that asthma caused their children to react to different environmental and viral triggers, leading to symptoms such as cough, wheezing and difficulty breathing. Latino parents interviewed in Spanish said, “Él tiene asma” (‘He has asthma’). Other parents made observations such as, “When he has a cold or flu, he is reactive,” or that sometimes her “asthma acts up,” or that “it’s like [asthma] is always there.” Consequently, many of these parents viewed daily medications as necessary. For example, one mother said “As long as she is on a 24/7/365 regimen, as long as she takes her medication on a daily basis, she builds up that wall she needs.” This concept of “building up a wall” was indicative of the chronic model in which the child had asthma and needed the medications to prevent flare-ups in the future.

3.2.3. The intermittent explanatory model

Sixteen of the 37 parents described an intermittent model of asthma. In this EM, asthma was not always present, but rather was something that was transitory. In Spanish, parents said “A él le da asma” or ‘He gets asthma.’ From this perspective, just as being exposed to a virus would give a child a cold, being exposed to a trigger would give a child asthma. One parent even said there was an asthma ‘germ.’ Another stated, “A cold triggers Alex’s asthma. As long as he doesn’t have a cold, he’s healthy.” Another parent, describing her son’s asthma stated:

When he’s having asthma, it’s bad; but when he’s not, he’s fine. So when it’s happening, it’s not good; but when it’s good, it’s good.

In this model, asthma was viewed as an acute illness, something that “comes and goes,” and does not exist in between episodes when triggers “bring the asthma on”. When asthma did come, one could deal with it effectively after symptoms began.

3.2.4. Predictability

Parents described their children’s asthma in terms of the predictability of asthma symptoms. Some parents stated that they knew exactly what would trigger an asthma attack. One parent said about her child’s asthma, “I’ve become very good at treating it and hearing it, before it comes.” Others described their children’s asthma as unpredictable. One parent stated: “So, we can’t pinpoint what it is. We do not know what the triggers are. It could be anything. It could be everything. It could be nothing.”

3.3. Concordance, explanatory models and contextual factors

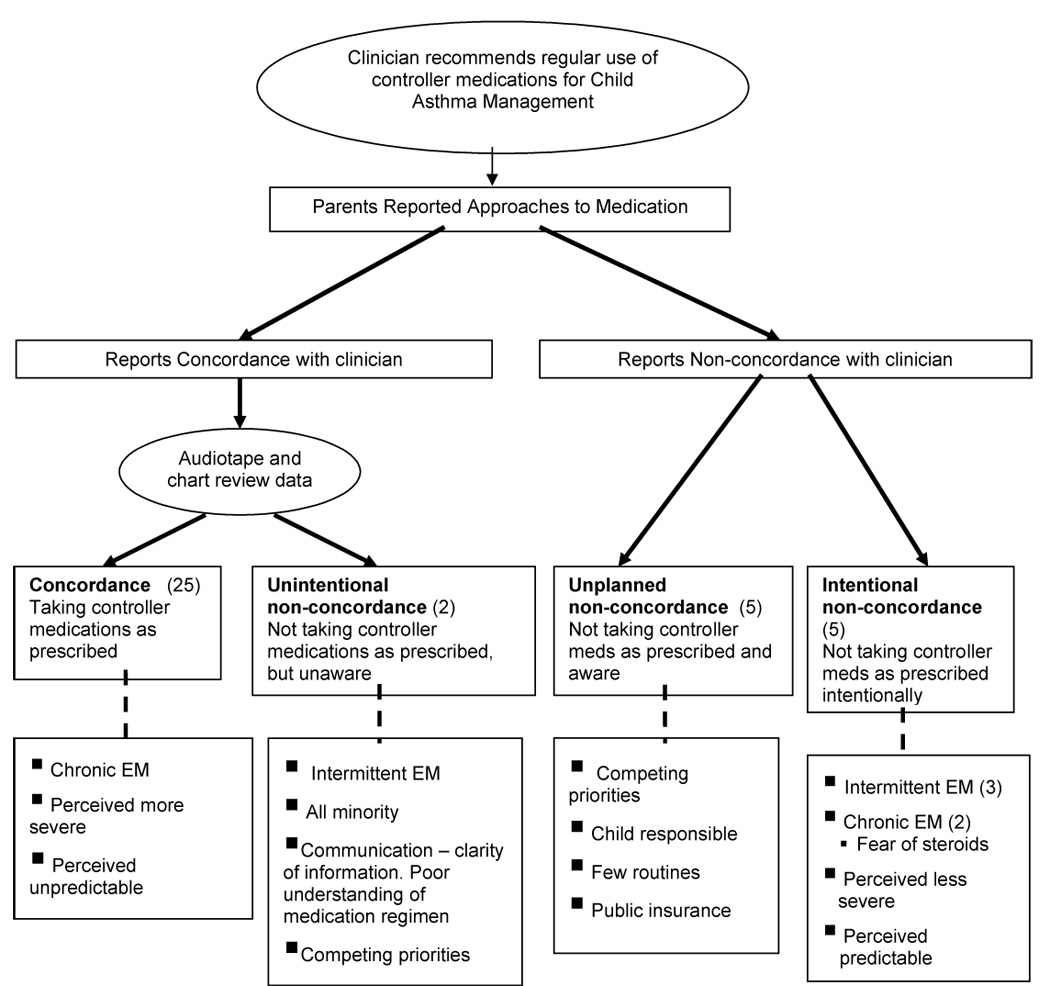

We developed a conceptual model to describe the patterns observed between concordance or non-concordance regarding medication use, EMs, contextual factors and sociodemographic factors (Figure 1). The analysis suggests a pattern regarding concordance or the type of non-concordance with clinician recommendations for controller medications and parents' EMs of asthma (Table 3). Of the 25 parents reporting concordance, 15 endorsed a chronic model of asthma. These parents also described their experiences with the medications as positive; for example, they have found that giving the inhaled steroid was effective in keeping their children healthy. The ten parents who endorsed an intermittent model and still reported concordance with clinician recommendations also described prolonged experience with asthma, the belief that their children’s asthma was unpredictable or severe, or the experience of a crisis.

Figure 1.

Emergent conceptual model of parent reported use of medication, explanatory models (EM) and other related factors

Table 3.

Type of concordance and Parents' Explanatory Models of Asthma

| N | Explanatory Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Intermittent | Chronic | ||

| Concordance | 25 | 10 | 15 |

| Non-concordance (all types) | 12 | 7 | 7 |

| Unintentional | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Intentional | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Unplanned | 5 | 1 | 4 |

Both parents (one African-American and one Spanish-speaking Latino) who described unintentional non-concordance had an intermittent EM. These parents had misinterpreted clinicians’ recommendations, believing that they were following instructions, but giving medications differently from how they were prescribed. These parents appeared to have limited knowledge about asthma and were confused about how to use medications.

For parents who described unplanned non-concordance, four out of five endorsed a chronic EM. However, they also described contextual barriers to using medications. For example, home life was described as a constant juggling of many competing priorities such as inadequate housing for their families, financial struggles and other family illnesses. Family life included few routines especially regarding taking medication. Some parents stated that they were not home when their child needed to take medication rendering the child responsible for his/her own medication. Other parents believed that their child, often younger than ten, was old enough to manage his/her own medications. All of these parents were on public insurance, suggesting lower socioeconomic status, although none reported financial barriers to obtaining medications. Rather, daily life obstacles faced by low-income families seemed to interfere with parents’ ability to give children controller medications consistently.

Parents who were intentionally non-concordant had one of two patterns. Three of these five endorsed an intermittent model and used controller medications sporadically. The other two parents endorsed a chronic model but expressed a fear of steroids.

I just think you hear so many things about steroids. When he was four months, he was given Prednisone, his teeth were coming out.… They got ruined … Some kids who get a lot of steroids, studies show that they have got hip replacements. Something that eats your bones or something.

Although other parents in the study expressed concern about steroids and giving medications, these two parents were explicit that their decisions not to give controller medications were due to their belief that all steroids, including ICS, were unhealthy.

All but one of the parents who were intentionally non-concordant also described their child’s asthma as predictable. This predictability allowed them to intervene with rescue medications as needed, or use controller medications on an interim basis to prevent the child from having an asthma attack in the presence of a trigger.

We found no pattern between educational level of the parent and type of concordance. Those with unintentional non-concordance were both minority parents, but no further pattern between race/ethnicity and concordance was found.

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Discussion

We found that non-concordance with clinician recommendations for asthma controller medications fell into three distinct types: unintentional, unplanned, and intentional. Previous literature on adherence distinguishes between adherence, non-adherence, and occasionally erratic adherence to describe patients who take medications inconsistently. We have identified clear distinctions between three types of non-concordance, based on the ways in which parents described how they give their children medications. Moreover, our findings suggest that the three types of non-concordance were aligned with different constellations of underlying factors, including features of explanatory models and unique contextual features of families’ lives. Consequently, clinical efforts to reduce medication underuse in children with asthma and other chronic conditions may be optimized by identifying different types of non-concordance and tailoring interventions accordingly.

The analysis crystallizes and expands existing knowledge by characterizing different types of non-concordance. The conceptual model we derived (Figure 1) suggests that under-utilization of medication may be due to different types of non-concordance; unintentional because one doesn’t understand how to use the medication, unplanned because one cannot manage the medication in a complex context, or intentional because one believes that taking medication intermittently is appropriate. Our finding that unintentional non-concordance was associated with communication barriers and racial/ethnic diversity concurs with previous work suggesting that parents frequently misunderstand their child's prescribed asthma regimen.3, 29 Even though the two parents in our study who had unintentional non-concordance were minorities, such communication barriers may well occur with many parents.

Consistent with previous findings that lack of routines are associated with medication non-adherence, we found that parents who reported unplanned non-concordance also reported high levels of competing priorities.30, 31 32 33 For example, parent work hours may require them to ascribe responsibility for administration of medication to very young children, which may further explain findings about young children being responsible for medication management.19 Our finding that intermittent EMs and fear of steroids may lead to intentional non-concordance augments previous studies that have identified low expectations of asthma control and concerns about medications as associated with medication underuse. 4, 15 Others have similarly found that patients’ beliefs about the nature of asthma are related to patients’ choices regarding asthma management.34, 35

4.2. Conclusion

Explanatory models have been identified in past literature as important for providers to consider when working with parents and children to enhance adherence to medications. Whereas others have found that perceptions of asthma as chronic led to adherence,17, 19, 34 we found that this explanatory model was not sufficient to support concordant medication use. Rather, perceptions of predictability, concerns about medications and complex family contexts with competing priorities were also noted when describing different types of non-concordance. Our observation that non-concordance appears related to these factors is an early finding, and deserves to be evaluated in future research.

4.3. Limitations

A qualitative approach enabled us to explore parents' perspectives, beliefs, and management of asthma in far greater depth than more commonly used survey methods. However, the intensive nature of qualitative research imposes some limitations. We relied on parents’ descriptions of giving medications. Because self-reported adherence is of variable validity 36, and we did not assess dosage of medications, it is possible that there was more intentional non-concordance than parents we identified. Our study population was unique in that it was located in the greater Boston area, and the academic hospital among our sites focuses on service to minority and low-income patients, but the clinical practices in our study populations do not differ greatly from those in other geographic areas. 37 We drew from a sample of 37 patients and subsequently some of our categories included as few as two parents.

Other factors we did not analyze in this study might contribute to parents' approaches to controller medication use. The parents we interviewed did not discuss financial barriers to medication use, however such barriers are well documented in the literature12. Further exploration of subthemes elucidating factors that contribute to parents’ EMs is also warranted. We did not evaluate parents' health literacy, which some studies of adult patients have found is associated with optimal health care practices 38, 39. Moreover, parents' individual experiences with asthma, neighborhood effects, cultural differences, and the experience of a crisis may all influence parents’ EMs and how they use medications. Further analysis of these factors may lead to refinements in the conceptual model we developed in this study.

4.4. Practice implications

These findings exploring the connections between types of non-concordance to different underlying factors have practical implications for how asthma care providers can address the problem of medication underuse (Table 4). As suggested by others, exploring parents’ explanatory models of asthma may be a powerful tool for providers to understand asthma management practices. 17–19 Exploring parents' EMs, and discussing parents’ beliefs about asthma and medications, particularly concerns about steroid use 4, 15, 40 appear to be most salient for parents who are intentionally non-concordant.

Table 4.

Recommendations for determining type of non-concordance and how to intervene

| Task | Question to ask | Response indicates | Clinician action |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Determine medication giving behavior | “Tell me what medication you are giving your child for asthma?” | Parent describes medication giving: | If non-concordant, determine type |

| ’When does he take the [controller medication]?” | Response indicates concordance or nonconcordance. | ||

| 2. Determining type of non-concordance | What is your understanding of how these medications should be taken? | Confusion: unintentional non-concordance | Provide education and explanation about prevention of asthma symptoms. Simplify medication instructions. Ask for parents’ to explain back their understanding. |

| Do you have any problems giving your child the controller medication every day? | Yes: Unplanned non-concordance | Ask about routines, competing priorities, who is responsible for medications. | |

| How do you feel about giving your child the [controller} medication? | Do not want to give medications: Intentional non-concordance | Ask about explanatory models: “Do you think your child has asthma all the time or only when he is having symptoms?“ 30 Explain chronicity of asthma – “Even when your child does not have asthma symptoms, he still has asthma.” Discuss risks and benefits of steroids. | |

We propose, moreover, that providers may potentially further tailor their discussions by first identifying the form of non-concordance by asking about medication routines, parents’ concerns about giving medications 41 42 and confirming parent comprehension of medication use through techniques such as teach-back methods. Non-concordance type may change over time, so discussions may need to occur repeatedly. Interventions to improve language competence, and the use of qualified medical interpreters, may also enhance optimal care.43–45

For families with unplanned non-concordance, clinicians could focus on helping families explore and address competing priorities so that asthma management routines can be implemented and sustained within the family context. This could be done through referrals to case management, social work, or other advocacy services to ensure that the family’s basic needs are being met 46. Additionally, clinicians may discuss what level of supervision parents need to give each child so that asthma medications are administered consistently. For those who are unintentionally non-concordant, a focus on simplifying explanations and giving clearer instructions may be of greatest consequence, either during the clinical encounter or in educational programs. Elucidating underlying concepts of chronicity, predictability and severity may help parents make decisions about managing asthma, and a focus on routines may help parents integrate medication regimes into their daily lives.47

Differences in both concordance and EMs may be subtle and the context in which parents care for their children with asthma is complex. Parents’ EM, influenced by the context in which they live, are filters through which parents interpret clinical advice and take it upon themselves to make management decisions they believe are best. Consequently, providers need to embrace this complexity and understand each individual parent and child within their dynamic social and cultural contexts in order to fully understand parents’ concordance. These findings suggest that improving medication use will require "sensitive interviewing and active listening” 9 to assess parents' approaches to medications and EMs of asthma during clinical encounters. Exploring parents’ underlying expectations, EMs, family dynamics, and social and cultural contexts that lead to different forms of non-concordance may produce more tailored interventions to reduce medication underuse.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to Jack Lasche, MD, and the clinicians in the Department of Pediatrics of Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates in West Roxbury; and Pauline Sheehan, MD, and the clinicians in the pediatric outpatient clinic at Boston Medical Center, for their support and encouragement. We appreciate the excellent work of our research assistants, Aarthi Iyer, Ludmilla Reategui-Sharpe, and Alexandra Meunze. We are indebted to the many parents who contributed their time and perspectives as participants in this research.

Supported by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (R01 HD044070). Dr. Lieu's effort was supported in part by a Mid-Career Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research from NICHD (K24 HD047667). Dr. Bokhour’s effort was supported in part by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Health Services Research & Development service. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Bokhour had full access to all the data in this study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.The Childhood Asthma Management Program Research Group. Long-term effects of budesonide or nedocromil in children with asthma. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1054–1063. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010123431501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donahue J, Weiss S, Livingston J, Goetsch M, Greineder D, Platt R. Inhaled steroids and the risk of hospitalization for asthma. J Amer Med Assoc. 1997;277:887–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farber HJ, Capra AM, Finkelstein JA, et al. Misunderstanding of asthma controller medications: association with nonadherence. J Asthma. 2003;40:17–25. doi: 10.1081/jas-120017203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conn KM, Halterman JS, Fisher SG, Yoos HL, Chin NP, Szilagyi PG. Parental beliefs about medications and medication adherence among urban children with asthma. Ambul Pediatr. 2005;5:306–310. doi: 10.1367/A05-004R1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finkelstein JA, Lozano P, Farber HJ, Miroshnik I, Lieu TA. Underuse of controller medications among Medicaid-insured children with asthma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:562–567. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.6.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauman L, Wright E, Leickly F, et al. Relationship of adherence to pediatric asthma morbidity among inner-city children. Pediatrics. 2002;110:1–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.1.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halterman J, Aligne A, Auinger P, McBride J, PG S. Inadequate therapy for asthma among children in the United States. Pediatrics. 2000;105:272–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warman K, Silver E, Stein R. Asthma symptoms, morbidity, and antiinflammatory use in inner-city children. Pediatrics. 2001;108:277–282. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rand CS. Non-adherence with asthma therapy: more than just forgetting. J Pediatr. 2005;146:157–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsui D. Clinical and research issues. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1997;44:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70459-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mansour M, Lanphear B, DeWitt T. Barriers to asthma care in urban children: parent perspectives. Pediatrics. 2000;106:512–519. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.3.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schafheutle EI, Hassell K, Noyce PR, Weiss MC. Access to medicines: cost as an influence on the views and behaviour of patients. Health Soc Care Community. 2002;10:187–195. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2524.2002.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bender BG, Bender SE. Patient-identified barriers to asthma treatment adherence: responses to interviews, focus groups, and questionnaires. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2005;25:107–130. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valerio M, Cabana MD, White DF, Heidmann DM, Brown R, Bratton Sl. Understanding of asthma management: Medicaid parents' perspectives. Chest. 2006:594–601. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.3.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoos HL, Kitzman H, McMullen A. Barriers to anti-inflammatory medication use in childhood asthma. Ambul Pediatr. 2003;3:181–190. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2003)003<0181:btamui>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kleinman A, Eisenberg L, Good B. Culture, illness, and care: clinical lessons from anthropologic and cross-cultural research. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88:251–258. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-88-2-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Handelman L, Rich M, Bridgemohan C, Schneider L. Understanding pediatric inner-city asthma: an explanatory model approach. Journal of asthma. 2004;41:167–177. doi: 10.1081/jas-120026074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoos H, Kitzman H, McMullen A. Barriers to anti-inflammatory medication use in childhood asthma. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2003;3:181–190. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2003)003<0181:btamui>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoos HL, Kitzman H, Henderson C, et al. The impact of the parental illness representation on disease management in childhood asthma. Nursin Research. 2007;56:167–174. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000270023.44618.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bissell P, May CR, Noyce PR. From compliance to concordance: barriers to accomplishing a re-framed model of health care interactions. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:851–862. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pound P, Britten N, Morgan M, et al. Resisting medicines: a synthesis of qualitative studies of medicine taking. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:133–155. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wahl C, Gregoire JP, Teo K, et al. Concordance, compliance and adherence in healthcare: closing gaps and improving outcomes. Healthc Q. 2005;8:65–70. doi: 10.12927/hcq..16941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to Medication. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353:487–489. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lieu TA, Lozano P, Finkelstein JA, et al. Racial/ethnic variation in asthma status and management practices among children in managed medicaid. Pediatrics. 2002;109:857–865. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.5.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Committee for Quality Assurance. HEDIS 2005. Washington, DC: National Commitee for Quality Assurance; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Heart L, and Blood Institute. National Institutes of Health; Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. 1997:123–146.

- 27.Strauss AL. Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire] New York: Cambridge University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qualitative Solutions and Research. NUD*IST Vivo (Nvivo) Melbourne, Australia: Pty. Ltd.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donnelly J, Donnelly W, Thong Y. Inadequate parental understanding of asthma medications. Ann Allergy. 1989;62:337–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fiese BH, Wamboldt FS. Tales of pediatric asthma management: family-based strategies related to medical adherence and health care utilization. J Pediatr. 2003;143:457–462. doi: 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00448-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fiese BH, Wamboldt FS, Anbar RD. Family asthma management routines: connections to medical adherence and quality of life. J Pediatr. 2005;146:171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.08.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bartlett S, Lukk P, Butz A, Lanpros-Klein F, Rand C. Enhancing medication adherence among inner-city children with asthma: results from pilot studies. J Asthma. 2002;39:47–54. doi: 10.1081/jas-120000806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evans D, Mellins R, Lobach K, et al. Improving care for minority children with asthma: professional education in public health clinics. Pediatrics. 1997;99:157–164. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Halm EA, Mora P, Leventhal H. No symptoms, no asthma: the acute episodic disease belief is associated with poor self-management among inner-city adults with persistent asthma. Chest. 2006;129:573–580. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.3.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adams S, Pill R, Jones A. Medication, chronic illness and identity: the perspective of people with asthma. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:189–201. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00333-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lieu TA, Finkelstein JA, Lozano P, et al. Cultural competence policies and other predictors of asthma care quality for Medicaid-insured children. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e102–e110. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.e102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kalichman SC, Ramachandran B, Catz S. Adherence to combination antiretroviral therapies in HIV patients of low health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:267–273. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00334.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams M, Baker D, Parker R, Nurss J. Relationship of functional health literacy to patients' knowledge of their chronic disease: A study of patients with hypertension and diabetes. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:166–172. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Price D. Steroid phobia. Respirtory disease in practice. 1994:10–13. Autumn. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steele DJ, Jackson TC, Gutmann MC. Have you been taking your pills? The adherence-monitoring sequence in the medical interview. J Fam Pract. 1990;30:294–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bokhour BG, Berlowitz DR, Long JA, Kressin NR. How do providers assess antihypertensive medication adherence in medical encounters? J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:577–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00397.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hampers L, Cha S, Gutglass D, Binns H, Krug S. Language barriers and resource utilization in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatrics. 1999;103:1253–1256. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.6.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hampers LC, McNulty JE. Professional interpreters and bilingual physicians in a pediatric emergency department: effect on resource utilization. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:1108–1113. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.11.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Flores G. Lost in translation? Pediatric preventive care and language barriers. J Pediatr. 2006;148:154–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zuckerman B, Sandel M, Smith LA, Lawton E. Why pediatricians need lawyers to keep children healthy. Pediatrics. 2004:224–228. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fiese B, Wamboldt F. Family routines, rituals, and asthma management: a proposal for family-based strategies to increase treatment adherence. Family, Systems & Health. 2000;18:405–418. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Halm EA, Mra P, Leventhal H. No symptoms, no asthma: The acute episodic disease belief is associated with poor self-management among inner-city adults with persistent asthma. Chest. 2006;129:573–580. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.3.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]