The cloning, purification and crystallization of a bacterioferritin from M. tuberculosis together with preliminary X-ray characterization of its crystals are reported.

Keywords: bacterioferritins, iron storage, Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Abstract

Bacterioferritins (Bfrs) comprise a subfamily of the ferritin superfamily of proteins that play an important role in bacterial iron storage and homeostasis. Bacterioferritins differ from ferritins in that they have additional noncovalently bound haem groups. To assess the physiological role of this subfamily of ferritins, a greater understanding of the structural details of bacterioferritins from various sources is required. The gene encoding bacterioferritin A (BfrA) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis was cloned and expressed in Escherichia coli. The recombinant protein product was purified by affinity chromatography on a Strep-Tactin column and crystallized with sodium chloride as a precipitant at pH 8.0 using the vapour-diffusion technique. The crystals diffracted to 2.1 Å resolution and belonged to space group P42, with unit-cell parameters a = 123.0, b = 123.0, c = 174.6 Å.

1. Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is one of the most serious infectious diseases worldwide; according to the predictions of the World Health Organization, 36 million people will die of TB between 2002 and 2020 unless the spread of the disease is controlled (World Health Organization, 2002 ▶). Infection occurs via aerosol and the inhalation of just a few cells of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent of the disease, is sufficient for the pathogen to establish infection in the host (Houben et al., 2006 ▶; Cosma et al., 2003 ▶; Pieters & Gatfield, 2002 ▶). The currently prescribed regimen for TB patients requires the continuous intake of drugs for a minimum period of six months, which can often extend to an exhausting nine months or more (Mitchison, 2004 ▶). Incomplete follow-ups of this long treatment schedule often lead to the emergence of multidrug-resistant strains of M. tuberculosis. It is estimated that ∼450 000 cases of multidrug-resistant TB occur globally every year (World Health Organization, 2006 ▶). A serious limitation of the current TB treatment lies in its inability to completely eliminate the pathogen from the host: the dormant bacilli that persist only require a weakened immune response to reactivate at any time during a person’s life span (Stewart et al., 2003 ▶; O’Regan & Joyce-Brady, 2001 ▶). This precarious situation has necessitated an urgent search for new antitubercular drugs against novel targets and combined efforts by several organizations are presently under way to determine the three-dimensional structures of a large number of mycobacterial proteins for structure-based drug design (Terwilliger et al., 2003 ▶; TB Structural Genomics Consortium, 2000 ▶).

Iron is required for the growth of tubercle bacilli in broth culture as well as in macrophages and thus represents a crucial requirement for infection by this pathogen (De Voss et al., 1999 ▶; Rodriguez & Smith, 2003 ▶). Being essential for a diverse set of biochemical reactions such as respiration, oxygen activation and binding, synthesis of DNA, amino acids and organic acids, degradation of peroxides and superoxides and regulation of gene expression, iron is an important element for the pathogen as well as for the host (Andrews, 1998 ▶). Although iron is essential, excess free iron is potentially toxic as it catalyzes the production of reactive oxygen by Haber–Weiss/Fenton reactions, which cause oxidative damage to the cell. Thus, cellular levels of iron have to be tightly regulated, for which efficient iron-acquisition and storage mechanisms have been developed by all living organisms (Crichton, 2001 ▶).

Iron storage in cells is carried out by a superfamily of proteins known as ferritins that are found in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. The three-dimensional architecture of ferritins from different sources is highly conserved (despite low amino-acid sequence homology in some cases) and is composed of 24 subunits of 18–21 kDa (Carrondo, 2003 ▶; Lewin et al., 2005 ▶; van Eerde et al., 2006 ▶). Each of these subunits folds into a four-helix bundle, resulting in a supramolecular assembly in which a hollow spherical protein shell of 20–25 Å thickness surrounds a central cavity of ∼80 Å diameter within which iron is stored in the form of a hydrous ferric oxide mineral core. The protein shell has numerous pores and channels allowing the entry of iron into the cavity. Some of the bacterial ferritins (also known as bacterioferritins; Bfrs) also contain a haem moiety bound at the interface between two subunits. Although it has been suggested that haem may be required for iron extraction from the Bfr structure, the exact function of this ligand largely remains unknown (Andrews et al., 1995 ▶; Keren et al., 2004 ▶). Despite extensive structural and physical characterization of Bfrs from several bacteria, their physiological role in the survival of the bacteria is not clear in the majority of cases. Studies of Bfr mutants indicate that bacterioferritins can protect bacteria from iron overload, serve as an iron source when iron is limited and/or protect the bacterial cells/DNA against oxidative stress (Smith, 2004 ▶). The M. tuberculosis genome reveals the presence of two putative iron-storage proteins, namely BfrA (Rv1876), a bacterioferritin, and BfrB (Rv3841), a ferritin-like protein (Cole et al., 1998 ▶). As observed in several bacteria, these may perform analogous functions in iron detoxification and storage (Ma et al., 1999 ▶; Chen & Morse, 1999 ▶). It is possible that one of them might have an adaptive advantage over the other. In an environment in which iron abundance is rare, efficient control of iron storage may require more than a single Bfr protein. The essential requirement of ferritins/bacterioferritins for the survival of several prokaryotic pathogens makes these proteins very attractive targets for structure determination and inhibitor design. Significant differences are known to exist between the structures and subunit compositions of human ferritins and bacterioferritins (Yang et al., 2000 ▶). These structural differences can be exploited to design new inhibitors, which will specifically inhibit bacterioferritins without any adverse effect on the function(s) of human ferritins or human iron homeostasis. Here, we describe the cloning, expression, purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of recombinant BfrA from M. tuberculosis.

2. Experimental methods

2.1. Cloning

The gene encoding BfrA (Rv1876) was PCR-amplified using M. tuberculosis H37Rv genomic DNA as the template. The primers were designed based on the sequence available from EMBL/GenBank. The sequences of the forward and reverse primers were 5′-GAATTCGCTAGCGGATCCCAAGGTGATCCCGATGTTC-3′ and 5′-GAATTCAAGCTTATTATTTTTCGAACTGCGGGTGGCTCCAAGCGCTGGTCGGTGGGCGAGAGACGCAC-3′, respectively. The reverse primer was designed in such a manner that it adds a Strep-tag at the C-terminus of the expressed recombinant protein to facilitate its purification. The PCR-amplified gene was cloned into the pET21c vector (Novagen, USA) at NheI and HindIII sites. The correct coding sequence of the cloned gene was verified by nucleotide sequencing using standard primers for the T7 promoter and terminator.

2.2. Protein expression and purification

Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells were transformed with the recombinant plasmid and the transformants were directly used to inoculate LB medium (1 l) containing 50 µg ml−1 ampicillin. The culture was grown at 310 K (200 rev min−1) to an A 600nm of 0.6. Expression of the recombinant protein was induced by the addition of 1 mM IPTG followed by 3 h incubation at the same temperature. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4500g for 5 min at 277 K. The harvested cells were resuspended in 50 ml buffer A (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM PMSF and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol) and then lysed using a French press. The resulting lysate was centrifuged at 25 000g for 30 min at 277 K. The supernatant was loaded onto a 10 ml Strep-Tactin column (IBA, Germany) pre-equilibrated with buffer A; in order to remove unbound proteins, the column was washed with two column volumes of the same buffer. The protein was eluted with 2.5 mM desthiobiotin in 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM PMSF and 1 mM DTT. The purity of the protein was analyzed by SDS–PAGE on a 12.5% gel. In addition to its native amino-acid sequence, the recombinant protein has four extra residues at the N-terminus (ASGS) and ten residues at the C-terminus (SAWSHPQFEK); the last eight residues constitute the Strep-tag. The predicted molecular weight of this purified protein is 19.7 kDa. The protein was concentrated to ∼9 mg ml−1 using an Amicon stirred-cell concentrator (YM30 membrane). The protein concentration was determined by protein dye-binding assay as described by Bradford (1976 ▶).

2.3. Crystallization

Various commercial screens (Hampton Research, USA; Jena Biosciences, Germany; Qiagen, USA) were set up at 293 K for initial crystallization screening of the purified recombinant protein fused with a Strep-tag at the C-terminus. The hanging-drop vapour-diffusion technique in EasyXtal Tool plates (Qiagen, USA) was employed for all setups. Each well was filled with 500 µl reservoir solution and 5 µl drops of 9 mg ml−1 protein solution (in 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 2.5 mM desthiobiotin, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM PMSF and 1 mM DTT) were mixed with 5 µl reservoir solution on screw-in greaseless crystallization supports. Reddish brown crystals (Fig. 1 ▶) were obtained with a reservoir solution containing 1.6 M sodium chloride and 0.1 M Tris–HCl pH 8.0.

Figure 1.

Crystals of M. tuberculosis BfrA grew to dimensions of ∼0.3 × 0.3 × 0.2 mm using the hanging-drop method.

2.4. Data collection and processing

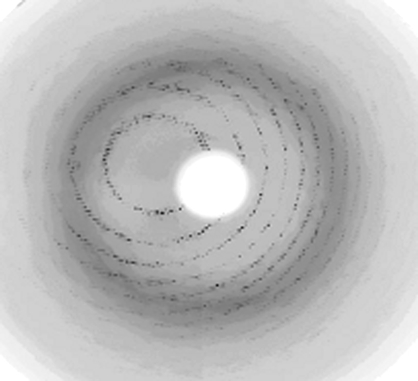

Initially, the crystals diffracted to low resolution (∼4 Å) on a home source. Stepwise increase of the glycerol concentration improved the diffraction to ∼3.0 Å resolution. This was accomplished by using a nylon-fibre loop to transfer a crystal to mother liquor supplemented with gradually increasing concentrations of glycerol ranging from 22% to 28.5% and leaving the crystal for 30 s in each solution. The crystal was then flash-cooled to ∼110 K in a nitrogen-gas stream. This treatment resulted in diffraction to 2.1 Å resolution at a synchrotron source (Fig. 2 ▶) using a 165 mm MAR CCD detector (beamline X13, EMBL, Hamburg, Germany). The crystal-to-detector distance was set to 180 mm and a total of 200 images were recorded with an oscillation angle of 0.5°, an exposure time of 140 s per image and a wavelength of 0.8088 Å. The data set was processed and scaled using HKL-2000 (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997 ▶). The data-collection and processing statistics are summarized in Table 1 ▶.

Figure 2.

X-ray diffraction pattern from a crystal of BfrA from M. tuberculosis. The edge of the frame is at 2.1 Å.

Table 1. Data-collection and processing statistics.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Source | Beamline X13, EMBL, Hamburg |

| Space group | P42 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å) | a = 123.0, b = 123.0, c = 174.6 |

| Temperature (K) | 120 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.8088 |

| Crystal-to-detector distance (mm) | 180 |

| Resolution limit (Å) | 25–2.1 (2.18–2.10) |

| Exposure time per image (s) | 140 |

| No. of observed reflections | 669724 |

| No. of unique reflections | 151083 |

| Average redundancy | 4.4 (4.0) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.7 (100) |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 18.09 (3.32) |

| Rmerge† (%) | 8.1 (42.9) |

| No. of molecules in ASU | 12 |

| Matthews coefficient (Å3 Da−1) | 2.89 |

| Solvent content (%) | 58 |

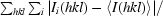

R

merge =

, where Ii(hkl) is the intensity of an individual measurement of the reflection with Miller indices hkl and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the mean intensity of redundant measurements of that reflection.

, where Ii(hkl) is the intensity of an individual measurement of the reflection with Miller indices hkl and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the mean intensity of redundant measurements of that reflection.

3. Results and discussion

BfrA from M. tuberculosis H37Rv was expressed in BL21 (DE3) cells, resulting in most of the recombinant protein being expressed in the soluble fraction. Alhough the final yield of purified protein was low (∼0.5 mg per litre of culture), the sample was ∼99% pure as analyzed by SDS–PAGE.

Initial crystallization screening provided several leads. The best crystals grew to dimensions of ∼0.3 × 0.3 × 0.2 mm in 1–2 weeks. The crystals belonged to point group P4, with unit-cell parameters a = 123.0, b = 123.0, c = 174.6 Å; assuming a 12-meric oligomer in the asymmetric unit, the crystals had a solvent content of 58% (the Matthews coefficient was 2.89 Å3 Da−1). The data-collection and processing statistics are given in Table 1 ▶.

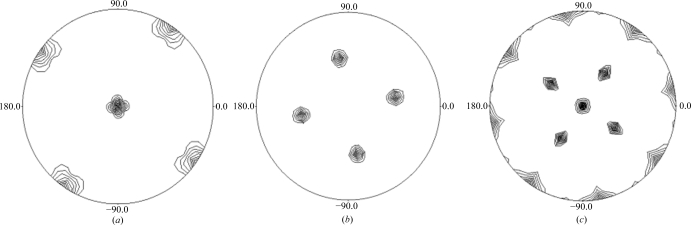

Bacterioferritins are generally composed of 24 monomeric subunits that fold as four-helix bundles and assemble to form a spherical protein shell with 432 cubic symmetry. The self-rotation Patterson maps (Fig. 3 ▶) show peaks consistent with 432 point-group symmetry typical of a 24-mer quaternary arrangement for the bacterioferritins. We are currently in the process of determining the structure by molecular replacement using Phaser (McCoy et al., 2007 ▶). The homologous bacterioferritins from M. smegmatis (87% sequence identity; PDB code 3bkn; R. Janowski, T. Auerbach-Nevo & M. S. Weiss, unpublished work), Azotobacter vinelandii (49% sequence identity; PDB code 2fkz; Swartz et al., 2006 ▶) and Rhodobacter capsulatus (45% sequence identity; PDB code 1jgc; Cobessi et al., 2002 ▶) will be used as initial search models.

Figure 3.

Self-rotation Patterson plots for M. tuberculosis BfrA in the resolution range 7–5 Å with an integration radius of 29 Å. The peaks in the κ = 90° (a), κ = 120° (b) and κ = 180° (c) sections confirm the 432 molecular symmetry. The maximum value was normalized to 100 and the contours are drawn at eight-unit intervals starting at 16. The self-rotation function was calculated using POLARRFN from the CCP4 suite (Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4, 1994 ▶) with default parameters. Drawings were prepared using PLTDEV.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by financial grants from the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India. GK is grateful to the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, India for a fellowship. We thank Remy Loris at VUB (Brussels, Belgium) and the beamline staff at EMBL (Hamburg, Germany) for their kind help with data collection and the DBT-Distributed Information Sub-Centre for providing computational facilities. Rajiv Chawla is acknowledged for efficient secretarial help.

References

- Andrews, S. C. (1998). Adv. Microb. Physiol.40, 281–351. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Andrews, S. C., Le Brun, N. E., Barynin, V., Thomson, A. J., Moore, G. R., Guest, J. R. & Harrison, P. M. (1995). J. Biol. Chem.270, 23268–23274. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bradford, M. M. (1976). Anal. Biochem.72, 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Carrondo, M. A. (2003). EMBO J.22, 1959–1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.-Y. & Morse, S. A. (1999). Microbiology, 145, 2967–2975. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cobessi, D., Huang, L.-S., Ban, M., Pon, N. G., Daldal, F. & Berry, E. A. (2002). Acta Cryst. D58, 29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cole, S. T. et al. (1998). Nature (London), 393, 537–544.

- Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 (1994). Acta Cryst. D50, 760–763.

- Cosma, C. L., Sherman, D. R. & Ramakrishnan, L. (2003). Annu. Rev. Microbiol.57, 641–676. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Crichton, R. (2001). Inorganic Biochemistry of Iron Metabolism: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Consequences, pp. 133–165. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- De Voss, J. J., Rutter, K., Schroeder, B. G. & Barry, C. E. (1999). J. Bacteriol.181, 4443–4451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Eerde, A. van, Wolterink-van Loo, S., van der Oost, J. & Dijkstra, B. W. (2006). Acta Cryst. F62, 1061–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Houben, E. N., Nguyen, L. & Pieters, J. (2006). Curr. Opin. Microbiol.9, 76–85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Keren, N., Aurora, R. & Pakrasi, H. B. (2004). Plant Physiol.135, 1666–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lewin, A., Moore, G. R. & Le Brun, N. E. (2005). Dalton Trans., pp. 3597–3610. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ma, J. F., Ochsner, U. A., Klotz, M. G., Nanayakkara, V. K., Howell, M. L., Johnson, Z., Posey, J. E., Vasil, M. L., Monaco, J. J. & Hassett, D. J. (1999). J. Bacteriol.181, 3730–3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McCoy, A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Adams, P. D., Winn, M. D., Storoni, L. C. & Read, R. J. (2007). J. Appl. Cryst.40, 658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mitchison, D. A. (2004). Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med.25, 307–315. [DOI] [PubMed]

- O’Regan, A. & Joyce-Brady, M. (2001). BMJ, 323, 635. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. (1997). Methods Enzymol.276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pieters, J. & Gatfield, J. (2002). Trends Microbiol.10, 142–146. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, G. M. & Smith, I. (2003). Mol. Microbiol.47, 1485–1494. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Smith, J. L. (2004). Crit. Rev. Microbiol.30, 173–185. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Stewart, G. R., Robertson, B. D. & Young, D. B. (2003). Nature Rev. Microbiol.1, 97–105. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Swartz, L., Kuchinskas, M., Li, H., Poulos, T. L. & Lanzilotta, W. N. (2006). Biochemistry.45, 4421- 4428. [DOI] [PubMed]

- TB Structural Genomics Consortium (2000). http://www.webtb.org/.

- Terwilliger, T. C. et al. (2003). Tuberculosis, 83, 223–249. [DOI] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (2002). Tuberculosis. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/who104/en/print.html. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (2006). 2006 Tuberculosis Facts. http://www.who.int/entity/tb/publications/2006/tb_factsheet_2006_1_en.pdf. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Yang, X., Le Brun, N. E., Thomson, A. J., Moore, G. R. & Chasteen, N. D. (2000). Biochemistry, 39, 4915–4923. [DOI] [PubMed]