Abstract

Understanding the effects of the external environment on bacterial gene expression can provide valuable insights into an array of cellular mechanisms including pathogenesis, drug resistance, and, in the case of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, latency. Because of the absence of poly(A)+ mRNA in prokaryotic organisms, studies of differential gene expression currently must be performed either with large amounts of total RNA or rely on amplification techniques that can alter the proportional representation of individual mRNA sequences. We have developed an approach to study differences in bacterial mRNA expression that enables amplification by the PCR of a complex mixture of cDNA sequences in a reproducible manner that obviates the confounding effects of selected highly expressed sequences, e.g., ribosomal RNA. Differential expression using customized amplification libraries (DECAL) uses a library of amplifiable genomic sequences to convert total cellular RNA into an amplified probe for gene expression screens. DECAL can detect 4-fold differences in the mRNA levels of rare sequences and can be performed on as little as 10 ng of total RNA. DECAL was used to investigate the in vitro effect of the antibiotic isoniazid on M. tuberculosis, and three previously uncharacterized isoniazid-induced genes, iniA, iniB, and iniC, were identified. The iniB gene has homology to cell wall proteins, and iniA contains a phosphopantetheine attachment site motif suggestive of an acyl carrier protein. The iniA gene is also induced by the antibiotic ethambutol, an agent that inhibits cell wall biosynthesis by a mechanism that is distinct from isoniazid. The DECAL method offers a powerful new tool for the study of differential gene expression.

The analysis of bacterial responses to environmental stimuli can provide valuable insights into cellular mechanisms (1–5). This approach is particularly well suited for studies of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a pathogen that must adapt to a variety of hostile milieu including phagocytosis by macrophages and treatment with antibiotics. Differential gene expression in bacteria has been difficult to study because the absence of poly(A)+ RNA complicates removal of abundant ribosomal rRNA from low-abundance mRNA. The number of differentially expressed genes that have been identified in bacteria has been limited (6–11), except under circumstances where large amounts of RNA can be obtained (12). It recently has become possible to monitor gene expression in multiple bacterial genes simultaneously by direct hybridization of total RNA to high-density DNA arrays (12). However, the large amounts of labeled RNA that must be hybridized to such arrays currently restricts their utility in many biologically relevant investigations. This problem is not resolved by amplification of samples with the PCR because it often is not possible to amplify complex mixtures of mRNA sequences while at the same time maintaining their relative proportions (13).

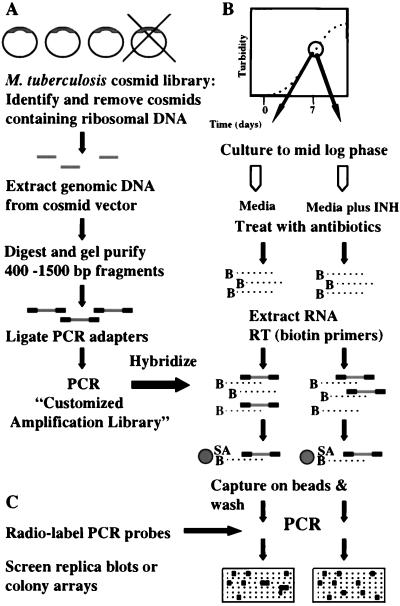

We describe a new approach to study differences in mRNA expression, which we term “differential expression using customized amplification libraries” (DECAL), that permits global comparisons of bacterial gene expression under varied growth conditions without a specific requirement for DNA arrays. The key feature of DECAL technology is the ability to amplify by PCR a complex mixture of expressed genes in a reproducible and representative manner without the confounding effects of rRNA or any other highly expressed gene product. We have found that three steps are essential for this process: (i) removal of abundant sequences—in this case rRNA sequences; (ii) reduction in the complexity of the sequences and conversion of all cDNA sequences into fragments of similar size; and (iii) selecting sequences that amplify efficiently. DECAL accomplishes this by creating a customized amplification library (CAL) of genomic sequences that has been manipulated for optimal performance during PCR amplification. Instead of amplifying total cDNA sequences, cDNA is hybridized to an excess of CAL, nonhybridizing CAL sequences are removed, and the remaining CAL sequences are amplified without altering their proportion representation. The amplified products derived from RNA samples can be hybridized to replicate colony blots or colony arrays, and the resulting hybridization patterns can be compared to determine the differentially expressed genes present in the original RNA samples. Here we describe the basic system, explore its limits of detection, and demonstrate its applicability to the study of M. tuberculosis gene expression in response to the antibiotic, isoniazid.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Libraries and Plasmids.

Cosmid libraries were constructed by ligation of Sau3A partial digests of M. tuberculosis H37Rv into pYUB328 (14). Plasmid libraries were constructed by ligation of complete PstI or SacI digests of M. tuberculosis H37Rv into pUC19 (15). The plasmid pUB124 was constructed by insertion of a 1.7-kb PstI fragment of the ask/asd operon containing the downstream portion of the M. tuberculosis ask gene and the complete asd gene into pKSII (16).

The plasmid PET-inhA, containing an 800-bp fragment of the M. tuberculosis inhA gene inserted into the BamHI site of pET-23a+ (Novagen), was a kind gift of John Blanchard (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY).

Creation of Ribosomal-Free Customized Amplification Libraries.

One thousand cosmid library clones were inoculated into “master” 96-well microtiter plates containing L broth and ampicillin 50 μg/ml, transferred by a pronged “frog” onto Biotrans nylon membranes (ICN), and hybridized separately with [α-32P]radiolabeled (Megaprime labeling kit, Amersham) PCR probes to M. tuberculosis ribosomal 5S, 16S, and 23S genes. Fourteen cosmids containing ribosomal DNA were identified; nonribosomal cosmids were reinoculated from master plates and individually cultured. Cosmids were extracted by SDS/alkaline lysis (17) in pools of 16. Cosmid DNA was pooled and digested with PacI, which does not restrict the M. tuberculosis genome, and insert DNA was purified from an agarose gel by electroelution. Approximately 1 μg of precipitated DNA was digested with AluI and 100 ng was run on a 2% NuSieve GTG low-melting-point agarose gel (FMC). Marker DNA was run simultaneously in a separate gel to avoid cross-contamination of samples. The gels were aligned, and the section corresponding to 400–1,500 bp of the AluI digest was excised. Five microliters of gel slice was ligated with 1 μl of Uniamp XhoI adapters (2 pmol/μl) (CLONTECH) in 20 μl total volume. Ten microliters of the ligation was PCR-amplified with 2 μl of 10 μM Uniamp primers (CLONTECH), 1× vent polymerase buffer, and 0.8 units of Vent (exo-) polymerase (New England Biolabs) in 100 μl total volume. After a 5-min hot start, 10 cycles of PCR with 1-min segments of 95°C, 65°C, and 72°C were followed by the addition of 3.2 units of Vent (exo-) polymerase and 27 additional cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 65°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 3 min. Uniamp primer sequence: 5′-CCTCTGAAGGTTCCAGAATCGATAG-3′; Uniamp XhoI adapter sequence, top strand: 5′-CCTCTGAAGGTTCCAGAATCGATAGCTCGAGT-3′; bottom strand: 5′-P-ACTCGAGCTATCGATTCTGGAACCTTCAGAGGTTT-3′.

RNA Extraction.

Mycobacterial cultures were grown to mid-log phase in Middlebrook 7H9 media supplemented with OADC/0.05% Tween 80/cyclohexamide (18) (for some experiments antibiotics were added for the last 18 hr), pelleted, resuspended in chloroform/methanol 3:1, and vortexed for 60 sec or until the formation of an interface occurred. RNA was extracted with five volumes of Triazole (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD), the aqueous layer was precipitated in isopropanol, and the RNA was redissolved in 4 M GTC, and extracted a second time with Triazole.

Positive Selection.

One microgram of RNA was reverse-transcribed with 7.7 μg biotin-labeled random hexamers and biotin dATP (one-tenth total dATP) by using superscript II (GIBCO/BRL) at 50°C for 1 hr, and RNase H then was added for 30 min at 37°C. Three hundred nanograms of CAL, 20 μg of salmon sperm DNA, and 20 μg of tRNA were added to the cDNA for a final volume of 150 μl. The sample was phenol/chloroform-extracted twice, ethanol-precipitated overnight, resuspended in 6 μl of 30 mM EPPS (Sigma), pH 8.0/3 mM EDTA, overlain with oil, and heated to 99°C for 5 min, and then 1.5 μl of 5 M NaCl preheated to 69°C was quickly added (19). The sample was incubated at 69°C for 3 to 4 days, then diluted with 150 μl of incubation buffer (1× TE/1 M NaCl/0.5% Tween 20) that had been preheated to 69°C, and 50 μl of washed, preheated streptavidin-coated magnetic beads (Dynal, Oslo) then were added. The sample was then incubated at 55°C with occasional mixing for 30 min and washed three times at room temperature and three times 30 min at 69°C with 0.1% SDS/0.2× SSC by placing the microfuge tubes into a larger hybridization tube in a rotating microhybridization oven (Bellco Glass). The sample was then washed with 2.5 mM EDTA and eluted by boiling in 80 μl of water. PCR was performed as in the CAL preparation by using 20 μl of sample in each reaction.

Colony Array Hybridizations.

Genomic plasmid library arrays were prepared by Genome Systems (St. Louis) by robotically double-spotting 9,216 colonies from the PstI and SacI plasmid libraries onto replicate nylon membranes. PCR probes were labeled by random priming with [α-32P]dCTP (Megaprime labeling kit, Amersham) for at least 6 hr, hybridized to the colony arrays in Rapid-hyb buffer (Amersham), washed at 69°C in 0.1× SSC/0.1% SDS, and visualized by autoradiography. Double-spotted colonies that hybridized at different intensities with two PCR probes were selected for further analysis.

Northern Blots.

Five micrograms of each RNA sample was analyzed by Northern blot with Northern Max kits (Ambion, Austin, TX) in a 1% denaturing agarose gel, probed with inserts of differentially expressed plasmids labeled by random priming with [α-32P]dCTP, and visualized by autoradiography.

Southern Blots.

Plasmid or genomic DNA was digested with restriction enzymes, subjected to electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel, and transferred by capillary action to Biotrans nylon membranes. The blots were hybridized and washed as in “colony array hybridizations” above and visualized by autoradiography.

Reverse Transcription–PCR (RT-PCR).

One microgram of RNA was reverse-transcribed by using the appropriate reverse PCR primer and superscript II at 50°C. For iniA and asd, three serial 10-fold dilutions of cDNA were made: 16S cDNA was diluted 1 in 106, 1 in 107, and 1 in 108. PCR was performed with Taq polymerase and 1× PCR buffer (GIBCO/BRL) containing 2 mM MgCl2 for 25 cycles annealing at 60°C for iniA, 35 cycles annealing at 58°C for asd, and 25 cycles annealing at 63°C for 16S. PCR products were analyzed on a 1.7% agarose gel, images were stored to disk by digital camera (Appligene, Strasbourg, France), and the amounts of PCR product were calculated by densitometry (Imaging Software, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Primers used for iniA were 5′-GCGCTGGCGGGAGATCGTCAATG-3′, 5′-TGCGCAGTCGGGTCACAGGAGTCG-3′; for asd, they were 5′-TCCCGCCGCCGAACACCTA-3′, 5′-GGATCCGGCCGACCAGAGA-3′; and for 16S, they were 5′-GGAGTACGGCCGCAAGGCTAAAAC-3′, 5′-CAGACCCCGATCCGAACTGAGACC-3′.

In Vitro Synthesis of inhA and ask/asd mRNA.

Plasmid vectors PET-inhA (inhA mRNA synthesis) and pUB124 (ask/asd mRNA synthesis) were digested with HindIII and BstXI, respectively, to terminate transcription immediately downstream of the transcribed genes. Transcription was performed for 1 hr at 37°C in 1× transcription buffer (Promega) containing 500 ng of restricted plasmid DNA, 0.4 mM NTPs, 40 units RNAsin (Promega), and either 60 units of T7 RNA polymerase (Promega) for PET-inhA or 60 units of T3 RNA polymerase (Promega) for pUB124. One unit of DNase (DNase R1Q, Promega) then was added to each tube and the reaction was incubated for an additional 30 min. RNA was purified after DNase treatment by using RNeasy columns (Qiagen) and quantitated by spectrophotometry. Complete plasmid DNase treatment and mRNA synthesis was confirmed both on nondenaturing and denaturing agarose gels.

RESULTS

Creation of an M. tuberculosis CAL.

A representative genomic library of the entire M. tuberculosis genome was “customized” for proportional amplification by PCR (Fig. 1A). A critical requirement for the amplification library was that all DNA-encoding rRNA genes had to be removed completely so that these highly abundant sequences could not confound proportional amplification in subsequent steps. This was performed by screening an M. tuberculosis cosmid library for rRNA gene sequences and removing all positive clones. The remaining rRNA-free M. tuberculosis genomic sequences were excised from their cosmid vector and pooled. A second requirement was that the amplification library contain DNA sequences of relatively uniform size and that their complexity be reduced in comparison with the entire M. tuberculosis genome. This was accomplished by restricting the excised inserts with AluI into small fragments and recovering the sequences between 400 and 1,500 bp in length by gel purification. The purified sequences were ligated to adapters for subsequent PCR. The final requirement for the amplification library was that all CAL sequences needed to be efficiently amplifiable by PCR. The AluI enzyme typically restricts M. tuberculosis ORFs several times; we selected for the most efficiently amplifiable fragments by subjecting the library to a number PCR cycles before the subsequent hybridization steps.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of DECAL. (A) Generation of CAL. A cosmid library is screened for clones that contain ribosomal DNA sequences. Nonribosomal cosmids are digested into similar-sized fragments, gel-purified, ligated to PCR adapters, and PCR-amplified. (B) Positive selection and hybridization. Reverse-transcribed RNA samples are hybridized to a ribosomal DNA-free CAL, washed, then amplified to generate PCR probes. (C) The probes are labeled and hybridized to replicate colony arrays of genomic plasmid libraries. Colonies that hybridize with differing intensities to two PCR probes are selected for evaluation of differentially expressed sequences.

Liquid Hybridization and Positive Selection.

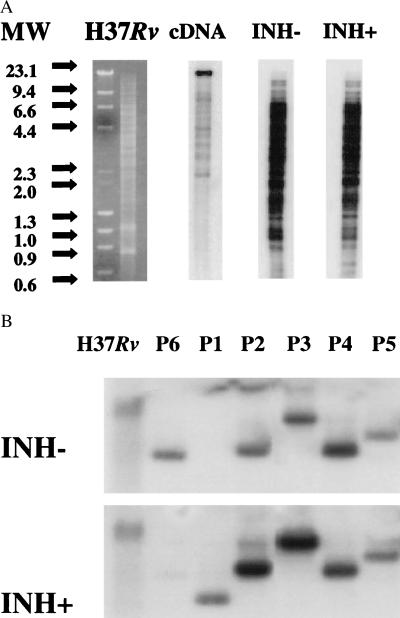

During positive selection, cDNA is hybridized to the CAL, and CAL sequences that are noncomplementary to the cDNA are removed (Fig. 1B). To identify the M. tuberculosis genes that were induced by isoniazid, M. tuberculosis was cultured to mid-log phase; the culture was then split and grown an additional 18 hr either in the absence (INH−) or presence (INH+) of isoniazid (1 μg/ml). Total cellular RNA was then extracted separately from both cultures and reverse-transcribed to biotin labeled cDNA. The biotin cDNA was used to capture complementary CAL sequences on streptavidin beads. The beads were extensively washed, and the remaining CAL sequences were reexpanded by PCR. We term the products of this procedure “PCR probes.” Despite the fact that the biotin cDNA from each sample was primarily ribosomal, neither INH− nor INH+ PCR probes contained ribosomal sequences because no amplifiable ribosomal DNA was present in the CAL. However, each PCR probe hybridized to multiple nonribosomal sequences when tested against an M. tuberculosis PvuII genomic digest (Fig. 2A) or assayed for hybridization to M. tuberculosis groES and hsp65 DNA and randomly selected M. tuberculosis cosmids (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Hybridization of PCR probes to genomic DNA and plasmid digests. DECAL was performed by using RNA extracted from M. tuberculosis H37Rv cultures that were either untreated (INH−) or treated with isoniazid 1.0 μg/ml for 18 hr (INH+). (A) Radiolabeled INH− cDNA (before positive selection with CAL) and radiolabeled INH− and INH+ PCR probes (after positive selection with CAL and amplification) were hybridized to H37Rv genomic digests. The cDNA hybridized almost exclusively with a single band of ribosomal DNA. The INH− PCR probe and INH+ PCR probe both hybridized to multiple sequences in the M. tuberculosis chromosomal digests, but showed no hybridization to the ribosomal band. (B) Southern blots of M. tuberculosis H37Rv genomic DNA digested with PvuII and PstI digests of six plasmids (P1–P6) that hybridized differentially to the PCR probes on colony array screening. Southern blots were hybridized with radiolabeled INH− PCR probe (Upper) or INH+ PCR probe (Lower). The INH− PCR probe hybridized exclusively to P6. The INH+ PCR probe hybridized almost exclusively to P1 and preferentially to P2 and P3. P4 and P5 did not hybridize differently to the two probes and are unlikely to code for isoniazid-induced genes.

Detection and Evaluation of Differential Gene Expression.

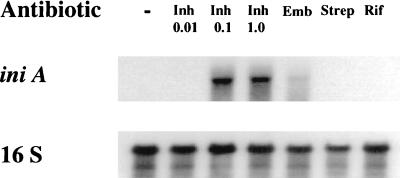

Differentially expressed genes were determined by examining the differential hybridization patterns of the PCR probes (Fig. 1C). PCR probes derived from INH− and INH+ RNA samples were radiolabeled and hybridized to replica membranes containing arrays of colonies from an M. tuberculosis genomic library. Hybridization signals to most colonies were equal when small differences in background were accounted for, but a subset of colonies was found to hybridize more strongly to either the INH− or INH+ probe. Six colonies were selected for further evaluation; five hybridized more strongly with the INH+ probe (P1-P5), and one hybridized more strongly with the INH− probe (P6). Differential hybridization was confirmed for P1, P2, P3, and P6 by rehybridizing the INH− and INH+ PCR probes to duplicate Southern blots of the excised plasmid inserts (Fig. 2B). P1 and P6 hybridized almost exclusively to the appropriate PCR probes, while P2 and P3 hybridized to both probes but with different intensities. P4 and P5 were found not to hybridize differentially on secondary screen. The ends of the plasmid inserts were sequenced and aligned to the completely sequenced M. tuberculosis genome (20). P1 and P2, which encoded sequences that hybridized almost exclusively with the INH+ probe, were homologous to a set of predicted proteins. P1 encoded a sequence identical to Rv0342, a large ORF that appeared to be the second gene of a probable three-gene operon. This ORF was named iniA (isoniazid-induced gene A), and the upstream ORF, Rv0341, was named iniB. P2 encoded a sequence that was not complementary to P1 but that was identical to the third gene in the same probable operon, Rv0343; this ORF was named iniC. A putative protein encoded by the iniA gene was found to contain a phosphopantetheine attachment site motif (21), suggesting that it functions as an acyl-carrier protein. Both iniA and iniC lacked significant homology to other known genes but were 34% identical to each other. A sequence similarity search demonstrated that iniB had weak homology to Ala-Gly-rich cell wall structural proteins (22). Northern blot analysis using excised inserts to probe total RNA from M. tuberculosis cultured in the presence or absence or different antibiotics verified that iniA was induced strongly by isoniazid and ethambutol, drugs that act by inhibiting cell wall biosynthesis, but not by rifampin or streptomycin, agents that do not act on the cell wall (Fig. 3). P3, which also encoded a sequence that preferentially hybridized to the INH+ probe, contained a 5-kb insert spanning M. tuberculosis cosmids MTCYH10 and MTCY21D4. This region contained multiple small ORFs, most with no known function. Northern blot analysis using the 5-kb insert as a probe confirmed that P3 preferentially hybridized to RNA from M. tuberculosis that had been cultured in the presence of isoniazid (data not shown). P6, which encoded a sequence hybridizing predominantly with the INH− probe, was found to encode l-aspartic-β-semialdehyde dehydrogenase (asd). The asd gene is an important component of the diaminopimelate pathway required for biosynthesis of the peptidoglycan component of bacterial cell walls. Modulation of asd by a cell wall antibiotic such as isoniazid is not unexpected.

Figure 3.

Induction of iniA after treatment with different antibiotics. Autoradiographs of a Northern blot containing RNA from M. tuberculosis cultures treated either with no antibiotics, 0.01 μg/ml isoniazid, 0.1 μg/ml isoniazid, 1 μg/ml isoniazid, 5 μg/ml ethambutol, 5 μg/ml streptomycin, and 5 μg/ml rifampin. The blots were hybridized first with an iniA DNA probe (Upper) to examine iniA induction; the blot was then stripped and rehybridized with a 16S probe (Lower) to confirm equal RNA loading.

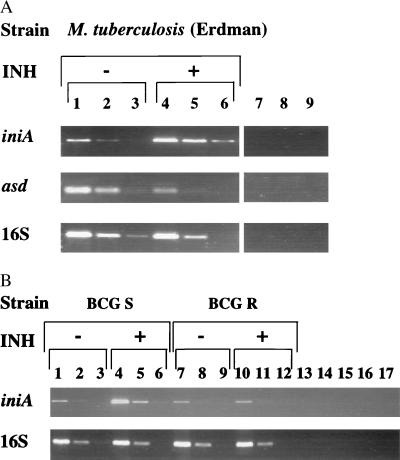

RT-PCR assays confirmed differential gene expression of both asd and iniA (Fig. 4A), as well as of iniB and iniC (data not shown). As predicted, iniA was induced strongly by isoniazid (70-fold induction by densitometry), while asd was repressed (17-fold). Induction of iniA also was tested in two isogenic strains of bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) that were either sensitive or resistant to isoniazid. The resistant phenotype was conferred by a mutation in katG, which normally converts isoniazid from a prodrug to its active form (23). Induction of iniA was seen only in the susceptible BCG strain demonstrating the requirement for isoniazid activation (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

RT-PCR of differentially expressed genes. (A) RNA was extracted from log-phase M. tuberculosis strain Erdman either without (lanes 1–3) or with (lanes 4–6) isoniazid added to the bacterial cultures for the last 18 hr. RNA from both cultures was equalized by comparison of the 23S band intensity. RT-PCR using three 10-fold dilutions of each RNA and either iniA, asd, or 16S specific primers was performed. Induction of iniA and suppression of asd by isoniazid are demonstrated. The amount of 16S RT-PCR product is similar for equivalent dilutions, indicating equal amounts of starting RNA. Lanes 7 and 8 are minus RT controls, and lane 9 is a negative PCR control. (B) Lack of iniA induction in an isoniazid-resistant strain. Cultures of isogenic BCG strain ATCC35735, which is susceptible to isoniazid (lanes 1–6), or ATCC35747, which is resistant to isoniazid (lanes 7–12), were incubated either in the presence or absence of isoniazid for the last 18 hr. Three 10-fold dilutions of RNA extracted from each culture were tested by RT-PCR for iniA induction. Induction is seen only in the INH-susceptible strain. Lanes 13–16 are minus RT controls, and lane 17 is a negative PCR control containing no added template.

Detecting Limited Differences in Gene Expression and Rare mRNAs.

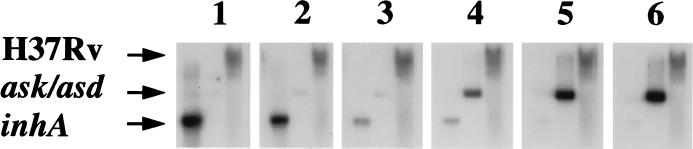

Most RNA-subtraction techniques have a limited ability to detect differentially expressed genes that are present in both bacterial populations. We determined that the DECAL method can distinguish small differences in gene expression and can detect rare mRNA sequences. Ten-fold dilutions of in vitro-transcribed mRNA from the M. tuberculosis inhA gene were added to six tubes, each containing 1 μg of BCG total RNA (equivalent to approximately 1 × 107 bacilli). In vitro-transcribed mRNA from the M. tuberculosis ask/asd operon was added to the same tubes in 4-fold increasing amounts. The DECAL method was performed separately on each tube, and the relative proportions of amplified inhA and ask/asd CAL sequences were measured by hybridization of each PCR probe to identical Southern blots (Fig. 5). Decreasing inhA signal is apparent from 1 × 1011 to 1 × 107 transcripts (1:20 wt/wt to 1:200,000 wt/wt) when normalized by equal hybridization to PvuII genomic digests of M. tuberculosis strain H37Rv. Increases in ask/asd signal can be detected beginning at 1.6 × 107 transcripts (1:64,000 wt/wt), and the signal clearly increased with each 4-fold increase in added transcript. At lower amounts of added ask/asd or inhA mRNA, the signal merged with the background from the BCG RNA present in each tube. These results demonstrate that representative and proportional amplification is maintained in six separate samples and confirm the ability of DECAL to detect small differences in gene expression for both high- and low-abundance mRNAs.

Figure 5.

Limits to distinguishing differences between samples. Ten-fold decreasing amounts of in vitro-transcribed M. tuberculosis inhA mRNA (tube 1 contained 1 × 1011 molecules; tube 2, 1 × 1010 molecules; tube 3, 1 × 109 molecules; tube 4, 1 × 108 molecules; tube 5, 1 × 107 molecules; tube 6, no added molecules) and 4-fold increasing amounts of ask/asd mRNA (tube 1 contained no added molecules; tube 2, 4 × 106 molecules; tube 3, 1.7 × 107 molecules; tube 4, 6 × 107 molecules; tube 5, 2.5 × 108 molecules; tube 6, 1 × 109 molecules) were added to six tubes. Each tube also contained 1 μg of BCG total RNA. DECAL was performed separately for each tube. The PCR probes then were hybridized to six Southern blots containing ask/asd DNA, inhA DNA, and M. tuberculosis H37Rv genomic digests. Autoradiography exposure was equalized to the hybridization intensity of the H37Rv bands.

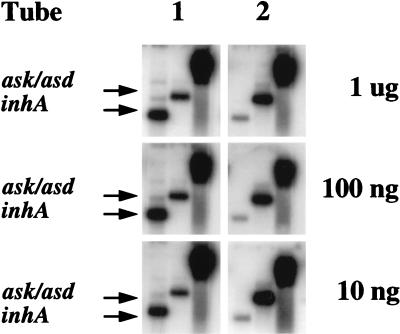

Differential Gene Expression in Small Quantities of RNA.

To investigate the sensitivity of the method, i.e., the minimum amount of starting RNA required, decreasing amounts of inhA mRNA and increasing amounts of ask/asd mRNA were added to two tubes, each containing 1 μg BCG total RNA. The tubes were reverse-transcribed with biotin random primers, and serial 10-fold dilutions of the cDNA, equivalent to 1 μg, 100 ng, and 10 ng of starting RNA, were assessed by DECAL for differences in inhA and ask/asd signals. The 10-fold differences in inhA mRNA and 4-fold differences in ask/asd mRNA could be detected easily even in the highest cDNA dilution (Fig. 6). Similar differences in mRNA were detectable when the serial 10-fold dilutions were performed before the reverse transcription step. These results indicate that DECAL is able to detect small differences in mRNA with limiting amounts of RNA starting material. Furthermore, only 1% of the total PCR probe generated from each tube pair was used in the experiment, indicating that even lower limits of detection are likely.

Figure 6.

Applying DECAL to small amounts of starting material. Ten-fold decreasing amounts (1 × 109 and 1 × 108 molecules) of inhA mRNA and 4-fold increasing amounts (1 × 108 and 4 × 108 molecules) of ask/asd mRNA were added to two tubes, each containing 1 μg of BCG total RNA. The tubes were reverse-transcribed with biotin random primers, and serial 10-fold dilutions of the cDNA (equivalent to 1 μg, 100 ng, and 10 ng of starting RNA) were subjected to the DECAL method. The resulting PCR probes were hybridized to duplicate Southern blots of a genomic M. tuberculosis H37Rv digest, inhA DNA, and ask/asd DNA to assess for the presence of detectable differences in inhA and ask/asd signal. Autoradiography exposure was equalized to the hybridization intensity of the H37Rv bands.

DISCUSSION

Current techniques to study differential gene expression in bacteria are limited by the problems associated with separating abundant rRNA sequences from mRNA and by the difficulty of achieving proportional amplification of sequences in complex PCRs. The present study describes a simple method for studying differential gene regulation between two bacterial populations. Differential gene expression is determined in a straightforward manner by comparing the relative intensity with which different PCR probes hybridize with individual colonies. Simultaneous detection of multiple genes can be performed, identifying both mRNA sequences that are uniquely present in one sample and those that are present in both samples but unequally represented. DECAL experiments are not dependent on poly(A)+-purified mRNA that is lacking in prokaryotes and can be performed without customized arrays and without knowledge of the entire bacterial sequence. DECAL may also enhance the sensitivity of DNA array-based detection methods by providing probes that can be PCR-amplified without significantly altering mRNA representation. DECAL should extend the applicability of DNA arrays to investigations where limited amounts of initial RNA is available.

Unlike total RNA or cDNA, customized amplification libraries can be manipulated in a variety of ways to fulfill specific requirements. For example, sets of CALs could be constructed that contain only a subset of the entire genome. This could be performed easily by using different restriction digests and more limited size fractionation during CAL preparation. CALs with more limited sequence representation might be advantageous when studying gene expression in eukaryotic organisms with larger genomes. While CALs require several weeks to construct, once prepared they are available for many experiments. DECAL also has the unique ability to allow unwanted RNA to be discarded without RNA subtraction because only mRNA sequences that have complementary CAL sequences can be represented in the final PCR probe. This property makes DECAL ideally suited for in vivo investigations where RNA samples may contain contaminating sequences from host tissue.

DECAL is critically dependent on removal of all nonhybridizing CAL sequences. This problem was solved by the development of a highly efficient wash protocol. During CAL preparation, some genes flanking the ribosomal gene sequences are removed along with the ribosomal coding cosmids; thus, inevitably some genes flanking the ribosomal gene sequences are removed along with the ribosomal-coding cosmids. However, we used cosmids with overlapping inserts for CAL construction; therefore, only a limited number of genes falling between the two Sau3A sites most proximal to the ribosomal DNA sequences will have been removed completely. Some genes may not have been digested into the 400- to 1,500-bp fragments used in CAL construction or may have been lost during the prehybridization-amplification step of CAL synthesis. A more complete CAL could be constructed by combining several digests made with different restriction enzymes.

DECAL was applied to study gene expression in M. tuberculosis after treatment with the antibiotic isoniazid. Isoniazid has long been a first-line drug for the treatment of tuberculosis (24); however, its full mechanism of action remains to be established (25, 26). Our discovery of genes that are induced by both isoniazid and ethambutol, two cell wall-active antibiotics that have different mechanisms of action (23, 25–28), adds further complexity to this issue. The role of the iniA operon is not well understood. The phosphopantetheine attachment site motif encoded by the iniA gene suggests that it encodes an acyl carrier protein; however, it may also have other functions. Another acyl carrier protein acpM has been described recently that both binds to and is induced by isoniazid (26). However, no gene in the iniA operon has significant homology to any gene in the operon containing acpM or to the antigen 85 complex that has also been shown to be induced by isoniazid (29). Unlike these genes, only iniA is induced by both isoniazid and ethambutol. We speculate that the iniA operon may be induced as a protective response to cell wall-mediated cellular injury. If this is the case, agents capable of blocking iniA, iniB, or iniC function would be expected to act synergistically with isoniazid and other cell wall-active antibiotics to kill M. tuberculosis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AI 45244 and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

ABBREVIATIONS

- DECAL

differential expression using customized amplification libraries

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription–PCR

- CAL

customized amplification library

- INH− and INH+

PCR probes derived from M. tuberculosis RNA either untreated or treated with isoniazid, respectively

- BCG

bacillus Calmette–Guérin

References

- 1. Sanders C C. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1987;41:573–593. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.41.100187.003041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller J F, Mekalanos J J, Falkow S. Science. 1989;243:916–922. doi: 10.1126/science.2537530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Korfmann G, Sanders C C, Morland E S. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:358–364. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.2.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beattie D T, Shahin R, Mekalanos J J. Infect Immun. 1992;60:571–577. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.2.571-577.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stragier P, Losick R. Annu Rev Genet. 1996;30:297–341. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathiopoulos C, Sonenshein A L. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:1071–1081. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Z, Brown D D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:11505–11517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kinger K A, Tyagi J S. Gene. 1993;131:113–117. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90678-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plum G, Clark-Curtis J E. Infect Immun. 1994;62:476–483. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.476-483.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong K K, McClelland M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:639–643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Utt E A, Brousal J P, Kikuta-Oshima L C, Quinn F D. Can J Microbiol. 1995;41:152–156. doi: 10.1139/m95-020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Saizieu A, Certa U, Warrington J, Gray C, Keck W, Mous J. Nat Biotech. 1998;16:45–48. doi: 10.1038/nbt0198-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marshall A, Hodgson J. Nat Biotech. 1998;16:27–31. doi: 10.1038/nbt0198-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balasubramanian V, Pavelka M S, Jr, Bardarov S S, Martin J, Weisbrod T R, McAdam R A, Bloom B R, Jacobs W R., Jr J Bacteriol. 1996;178:273–279. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.1.273-279.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller L P, Crawford J T, Shinnick T M. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:805–811. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.4.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cirillo J D, Weisbrod T R, Pascopella L, Bloom B R, Jacobs W R., Jr Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:629–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd Ed. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobs W R, Kalpana G V, Cirillo J D, Pascopella L, Snapper S B, Udani R A, Jones W, Barletta R G, Bloom B R. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:537–555. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04027-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lisitsyn N, Lisitsyn N, Wigler M. Science. 1993;259:946–951. doi: 10.1126/science.8438152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cole S T, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon S V, Eiglmeier L, Gas S, Barry C E, III, et al. Nature (London) 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bairoch A, Bucher P, Hofmann K. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:217–221. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.1.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y, Heym B, Allen B, Young D, Cole S. Nature (London) 1992;358:591–593. doi: 10.1038/358591a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bass J B, Jr, Farer L, S, Hopewell P C, O’Brien R, Jacobs R F, Ruben F, Snider D E, Jr, Thornton G. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:1359–1374. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.5.8173779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banerjee A, Dubnau E, Quemard A, Balasubramanian V, Um K S, Wilson T, Collins D, de Lisle G, Jacobs W R., Jr Science. 1994;263:227–230. doi: 10.1126/science.8284673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mdluli K, Slayden R A, Zhu Y, Ramaswamy S, Pan X, Mead D, Crane D D, Musser M J, Barry C E., III Science. 1998;280:1607–1610. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belanger A E, Besra G S, Ford M E, Mikusova K, Belisle J T, Brennan P J, Inamine J M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11919–11924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Telenti A, Philipp W J, Sreevatsan S, Bernasconi C, Stockbauer K E, Wieles B, Musser J M, Jacobs W R., Jr Nat Med. 1997;3:567–570. doi: 10.1038/nm0597-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garbe, T. R., Hibler, N. S. & Deretic, V. (1996) 40, 1754–1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]