Abstract

The PRNP polymorphic (methionine/valine) codon 129 genotype influences the phenotypic features of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy. All tested cases of new variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (nvCJD) have been homozygous for methionine, and it is conjectural whether different genotypes, if they appear, might have distinctive phenotypes and implications for the future “epidemic curve” of nvCJD. Genotype-phenotype studies of kuru, the only other orally transmitted transmissible spongiform encephalopathy, might be instructive in predicting the answers to these questions. We therefore extracted DNA from blood clots or sera from 92 kuru patients, and analyzed their codon 129 PRNP genotypes with respect to the age at onset and duration of illness and, in nine cases, to detailed clinical and neuropathology data. Homozygosity at codon 129 (particularly for methionine) was associated with an earlier age at onset and a shorter duration of illness than was heterozygosity, but other clinical characteristics were similar for all genotypes. In the nine neuropathologically examined cases, the presence of histologically recognizable plaques was limited to cases carrying at least one methionine allele (three homozygotes and one heterozygote). If nvCJD behaves like kuru, future cases (with longer incubation periods) may begin to occur in older individuals with heterozygous codon 129 genotypes and signal a maturing evolution of the nvCJD “epidemic.” The clinical phenotype of such cases should be similar to that of homozygous cases, but may have less (or at least less readily identified) amyloid plaque formation.

New variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (nvCJD), the probable consequence of eating beef contaminated with the infectious agent of bovine spongiform encephalopathy, can be distinguished from sporadic cases of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease by an early age at onset (average, 27 yr), a clinical presentation with psychiatric or sensory symptoms, the absence of periodic electroencephalogram activity, a comparatively long duration (average, 14 mo), and a neuropathological picture featuring an abundance of amyloid plaques surrounded by halos of spongiosis (“daisy plaques”) (1, 2). All 26 tested cases have shown a homozygous methionine genotype at polymorphic codon 129 of the PRNP gene located on chromosome 20 (ref. 3; R. Will, personal communication).

It is possible that as time goes on, nvCJD cases may begin to occur with codon 129 genotypes other than methionine homozygosity, which could have a sufficiently different clinicopathological phenotype to present a problem in recognition and diagnosis.

Kuru, the prototype human transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE), was spread by exposure to contaminated human tissues through the practice of ritual endocannibalism, and is by virtue of its oral and/or mucocutaneous route of infection the most appropriate comparison for nvCJD. Here, we compare codon 129 genotypes to age at onset and duration of illness for 92 kuru patients dying in the late 1950s, at the height of the kuru epidemic, of which nine cases had been the subject of extensive neuropathological examination (4).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We retrieved a total of 92 frozen blood clots and sera from our tissue bank archives, stored at −20°C since collection in Papua, New Guinea in 1957–1958. Genomic DNA was extracted from blood clots after treatment with proteinase K using a standard phenol-chloroform extraction method and from sera using the Puregene DNA isolation kit (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN), with the following slight modification: 500 μl of plasma was centrifuged for 30 sec at 13,000 rpm in a microfuge (Beckman, Palo Alto, CA) and pelleted cells were treated with 300 μl of cell lysis solution. Further steps were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The 169-bp fragment of the PRNP gene spanning codons 94 through 150 was amplified by PCR using TaKaRa Ex Taq polymerase (TaKARA Shuzo Co., Shiga, Japan) and oligonucleotide primers (GenSet Corp., La Jolla, CA) 5′- cacccacagtc agtggaa-3′ and 5′-atagtaacggtcctcatagtca-3′ under the following conditions: an initial denaturation (95°C, 3 min) followed by 35 cycles of denaturation (94°C, 30 sec), annealing (60°C, 30 sec), extension (72°C, 30 sec), and a final elongation (72°C, 5 min). The ATG/GTG polymorphism at codon 129 was screened in the amplified samples using endonuclease MaeII (Boehringer Mannheim) or TaiI (MBI Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania) (5). Digested fragments were resolved in a 3% MetaPhor agarose gel (FMC BioProducts, Rockland, ME) stained with ethidium bromide. Codon 129 genotypes (MM, VV, or MV) were determined on the basis of the distinct restriction patterns seen for each genotype.

Comparisons of genotype frequencies between different age groups were made by using the two-tailed Fisher’s exact test.

RESULTS

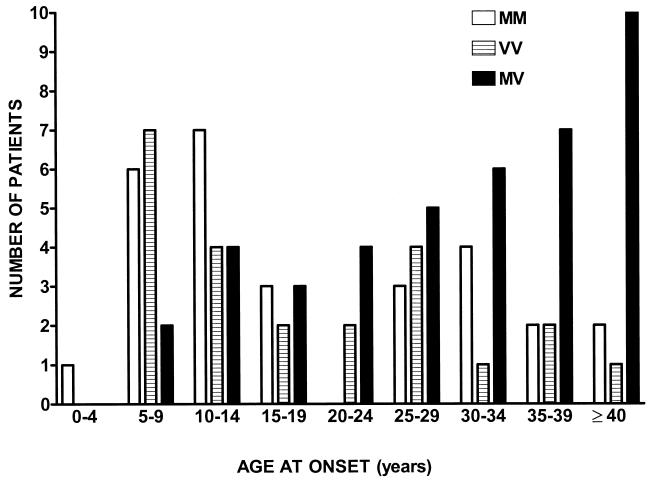

The distribution of homozygous methionine, homozygous valine, and heterozygous genotypes according to age at onset of kuru symptoms is shown in Fig. 1. It is evident that compared with the series as a whole, homozygous methionine patients are overrepresented in the younger age groups, and heterozygous patients are overrepresented in the older age groups. When the genotype frequencies of the group of children and young adolescents (<15 yr of age) were compared with adults >30 yr of age, the difference between homozygotes and heterozygotes was statistically significant (P = 0.0001), Table 1. A less impressive but still statistically significant correspondence also exists between the codon 129 genotype and the duration of illness, shorter illnesses being associated with homozygosity and longer illnesses being associated with heterozygosity (P = 0.006).

Figure 1.

Distribution of PRNP codon 129 genotypes according to age at onset of illness in 92 kuru patients.

Table 1.

PRNP codon 129 genotype frequencies in kuru patients

| Genotype frequency (proportion of total)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Met/Met | Met/Val | Val/Val | Total no. tested | |

| Age at onset of illness, yr | ||||

| <15 | 14 (0.45) | 6 (0.19) | 11 (0.36) | 31 |

| 15–30 | 10 (0.28) | 17 (0.47) | 9 (0.25) | 36 |

| >30 | 4 (0.16) | 18 (0.72) | 3 (0.12) | 25 |

| Duration of illness,* mo | ||||

| <8 | 6 (0.29) | 4 (0.19) | 11 (0.52) | 21 |

| 8–12 | 11 (0.42) | 10 (0.38) | 5 (0.19) | 26 |

| >12 | 2 (0.13) | 10 (0.67) | 3 (0.20) | 15 |

Information about duration of illness was incomplete for 30 cases, which were excluded from analysis.

Nine specimens in the series were matched with patients whose brains had earlier been the subject of extensive neuropathological examinations (4). An extract of these data is presented in Table 2, along with clinical summaries and codon 129 genotypes. Irrespective of the age at onset or duration of illness, or of the codon 129 genotype, all nine patients had a clinical picture dominated by progressive locomotor ataxia associated with the shivering tremor characteristic of kuru. The occurrence of extrapyramidal signs, strabismus, dysphagia, and mutism was also unrelated to age at onset or duration of illness, or to the codon 129 genotype.

Table 2.

Summary of clinicopathological phenotypes and codon 129 genotypes in nine kuru patients

| Case | Sex/age at onset | Duration of illness, mo | Clinical signs (all cases had progressive ataxia associated with tremor)

|

Pathology (all cases had severe gliosis in all brain regions)

|

Codon 129 genotype | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abnormal affect | Extrapyramidal | Other signs | Cerebral cortex | Basal ganglia | Thalamus | Pons/medulla | Cerebellum | ||||

| 6 | F/6 | 8 | + | Rigidity | Dysphagia | N | NV | NV | NV | Val/Val | |

| 7 | F/6 | 5 | − | − | Dysphagia, mutism | N | NV | N | N | Val/Val | |

| 16 | M/7 | 8 | − | − | Strabismus, mutism | NP | N | NP | NV | NVP | Met/Met |

| 8 | M/7 | 8 | + | ChAth | Myoclonus | N | NV | NV | N | NV | Val/Val |

| 24 | F/11 | 12 | + | − | Strabismus | P | NV | NVP | NV | NVP | Met/Met |

| 11 | F/13 | 5 | + | ChAth | Strabismus | N | N | NV | Val/Val | ||

| 10 | M/17 | 10 | − | − | Strabismus, mutism | (N) | NV | N | Val/Val | ||

| 2 | F/45 | 9 | − | ChAth | mutism | P | NV | NP | Met/Met | ||

| 4 | F/50 | 10 | + | − | Dysphagia, mutism | P | NV | NP | NV | NP | Met/Val |

ChAth, choreo-athetosis; N, neuronal changes; V, vacuolation; P, plaques.

In regard to neuropathology, widespread gliosis occurred in all cases, associated with a variable pattern of neuronal abnormalities and vacuolation that was unrelated to genotype. However, amyloid plaques were noted only in the four patients with at least one methionine allele, and not in the five patients with only valine alleles. Except for the presence of plaques, the lone heterozygote was neuropathologically indistinguishable from either the methionine or valine homozygotes.

DISCUSSION

One of the more interesting features of the chromosome 20 PRNP gene is the phenotypic influence of polymorphic codon 129. Although not in itself pathogenic, it has been shown to influence susceptibility to iatrogenic and sporadic forms of TSE and to affect age at onset and duration of illness in familial TSE; in association with a pathogenic mutation in codon 178, the entire disease phenotype is altered (5–11).

Because all cases of nvCJD recognized to date have tested homozygous for methionine at codon 129, it is not known whether other genotypes (should they occur) will change the nvCJD phenotype, possibly even to the point of obscuring its distinctive clinical and neuropathological features.

One clue that this may not happen comes from experience with iatrogenic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, resulting from peripheral injection by contaminated human growth hormone, which shows that, other than a longer period of latency between infection and the onset of symptoms, the clinicopathological picture of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease in patients with a heterozygous codon 129 genotype does not differ from that in patients with either methionine or valine homozygosity (ref. 12; D. Dormont, personal communication; M. Preece, personal communication).

An even more appropriate comparison comes from phenotype-genotype studies in kuru patients, in whom infection occurred, at least in part, by the oral route. Three recent studies comparing the neuropathological features of kuru and nvCJD include kuru cases in which the genotype of codon 129 was determined. In one study, the brains from two valine homozygotes showed a tendency for “proper plaque formation” in PrP-stained immunohistochemical sections (13). In another study, the brain from a valine homozygote showed numerous plaques by both histological and immunohistochemical staining (14). In the third study, brains from three valine and two methionine homozygotes had plaques visible by both histological and immunohistochemical staining, and no genotypic correlations were noticed (15).

In contrast to these studies, our series of nine cases showed a distinct correlation between the presence of the methionine allele and the presence of histologically recognizable amyloid plaques. It is possible that these differing results are a consequence of chance or of undefined differences in tissue fixation and staining methods. It is also possible that as a group, kuru cases with a valine allele at codon 129 have a comparatively reduced potential for plaque formation, and, by analogy, nvCJD cases with a codon 129 valine allele might not always show the prominent daisy plaque formation observed in methionine homozygotes.

Our finding that homozygotes have an earlier age at onset (and thus probably a shorter incubation period) than heterozygotes, but show a generally similar clinical phenotype, is in keeping with the effect of codon 129 homozygosity in other forms of TSE, and, if applicable to nvCJD, would predict (i) that codon 129 nvCJD heterozygotes will not pose a problem in recognition or diagnosis and (ii) that the appearance of an increasing proportion of heterozygotes may signal that the nvCJD epidemic is already evolving beyond its “leading edge,” and thus provide a more solid foundation for predictive modeling studies of its overall extent and duration.

ABBREVIATIONS

- nvCJD

new variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

- TSE

transmissible spongiform encephalopathy

References

- 1. Will R G, Ironside J W, Zeidler M, Cousens S N, Estibeiro K, Alperovitch A, Poser S, Pocchiari M, Hofman A, Smith P G. Lancet. 1996;347:921–925. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91412-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeidler M, Stewart G E, Barraclough C R, Bateman D E, Bates D, Burn D J, Colchester A C, Durward W, Fletcher N A, Hawkins S A, Mackenzie J M, Will R G. Lancet. 1997;350:903–907. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)07472-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeidler M, Stewart G, Cousens S N, Estibeiro K, Will R G. Lancet. 1997;350:668. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)63366-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klatzo I, Gajdusek D C, Zigas V. Lab Invest. 1959;8:799–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldfarb L G, Petersen R B, Tabaton M, Brown P, LeBlanc A C, Montagna P, Cortelli P, Julien J, Vital C, Perdelbury W W, et al. Science. 1992;258:806–808. doi: 10.1126/science.1439789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palmer M S, Dryden A J, Hughes J T, Collinge J. Nature (London) 1991;352:340–342. doi: 10.1038/352340a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dlouhy S R, Hsiao K, Farlow M R, Foroud T, Conneally P M, Johnson P, Prusiner S B, Hodes M E, Ghetti B. Nat Genet. 1992;1:64–67. doi: 10.1038/ng0492-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poulter M, Baker H F, Frith C D, Leach M, Lofthouse R, Ridley R M, Shah T, Owen F, Collinge J, Brown J, et al. Brain. 1992;115:675–685. doi: 10.1093/brain/115.3.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown P, Cervenáková L, Goldfarb L G, McCombie W R, Rubenstein R, Will R G, Pocchiari M, Martinez-Lage J F, Scalici C, Masullo C, et al. Neurology. 1994;44:291–293. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deslys J-P, Marcé D, Dormont D. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:23–27. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-1-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gambetti P, Parchi P, Petersen R B, Chen S G, Lugaresi E. Brain Pathol. 1995;5:43–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1995.tb00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deslys J P, Jaegly A, Huillard d’Algnaux J, Moulhon F, Billette de Villemeur T, Dormont D. Lancet. 1998;351:1251. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)79317-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lantos P L, Bhatia K, Doey L J, Al-Sarraj S, Doshi R, Beck J, Collinge J. Lancet. 1997;350:187–188. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)62355-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hainfellner J A, Liberski P P, Guiroy D C, Cervenáková L, Brown P, Gajdusek D C, Budka H. Brain Pathol. 1997;7:547–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1997.tb01072.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLean C A, Ironside J W, Alpers M, Cervenáková L, Anderson R M, Brown P W, Masters C L. Brain Pathol. 1998;8:429–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1998.tb00165.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]