Abstract

The RAS–ERK pathway is known to play a pivotal role in differentiation, proliferation and tumour progression. Here, we show that ERK downregulates Forkhead box O 3a (FOXO3a) by directly interacting with and phosphorylating FOXO3a at Ser 294, Ser 344 and Ser 425, which consequently promotes cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. The ERK-phosphorylated FOXO3a degrades via an MDM2-mediated ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. However, the non-phosphorylated FOXO3a mutant is resistant to the interaction and degradation by murine double minute 2 (MDM2), thereby resulting in a strong inhibition of cell proliferation and tumorigenicity. Taken together, our study elucidates a novel pathway in cell growth and tumorigenesis through negative regulation of FOXO3a by RAS–ERK and MDM2.

The constitutive activation of certain signal transduction cascades leads to the development of tumours and the resistance of tumours to clinical therapy1,2. The RAS–ERK pathway triggers one of these cascades and governs many important functions, such as cell fate, differentiation, proliferation and survival in invertebrate and mammalian cells3,4. Human tumours frequently overexpress RAS or harbour activated RAS with a point mutation, which contributes substantially to tumour cell growth, invasion and angiogenesis1,2,5–8. Cell plasma membrane receptor tyrosine kinases activate RAS GTPases, and GTP-bound RAS activates A-RAF, B-RAF and RAF-1 (ref. 4), leading to the phosphorylation and activation of the MEK1 and MEK2 pathway. ERK further amplifies the RAS–MEK signalling pathway by targeting different substrates, including transcription factors, kinases and phosphatases, cytoskeletal proteins and apoptotic proteins3–8. Recently, ERK and p38 were shown to phosphorylate FOXO1 at various sites9, suggesting that the RAS–MAPK signalling pathway may play a pivotal role in FOXO regulation.

FOXO transcription factors, one of large forkhead family members, include FOXO1, FOXO3, FOXO4 and FOXO6 (ref. 10). These FOXOs activate or repress multiple target genes involved in tumour suppression, such as Bim and FasL for inducing apoptosis11–13; p27kip1 (ref. 14) and cyclin D15 for cell cycle regulation, and GADD45a for DNA damage repair10,11,13,16. FOXO3a was shown to be associated with tumour suppression activity17 and inhibition of FOXO3a expression promotes cell transformation, tumour progression and angiogenesis10,17–19. More recently, the FOXOs (FOXO1, FOXO3 and FOXO4) knockout mouse has been shown to develop lymphomas and hemangiomas. Thus, the FOXOs function as bona fide tumour suppressors20. It is known that FOXO3a can be degraded by a ubiquitin-proteasome-dependent pathway10,17,18,21, but the E3 ubiquitin ligase responsible for FOXO3a degradation has yet to be identified. MDM2, an E3 ubiquitin ligase plays an important role in the development of multiple human cancers through degrading tumour suppressor proteins, such as p53, RB and E-cadherin22–25. In addition, MDM2 has been shown to be regulated by the RAS–ERK signalling pathway26 and blocking ERK activity with an MEK1 inhibitor, U0126, reduces MDM2 expression in breast cancer cells27.

Here, we identify a novel pathway involving the downregulation of FOXO3a expression by RAS–ERK and MDM2, which leads to promotion of cell growth and tumorigenesis. We show that ERK interacts with and phosphorylates FOXO3a at Ser 294, Ser 344 and Ser 425; phosphorylation of FOXO3a at these residues increases FOXO3a–MDM2 interaction and enhances FOXO3a degradation via an MDM2-dependent ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. The non-phosphorylated FOXO3a-mimic mutant, compared to the phosphorylated FOXO3a-mimic mutant, exhibits more resistance to the interaction and degradation by MDM2, resulting in a strong inhibition of cell proliferation in vitro and tumorigenesis in vivo.

RESULTS

ERK suppresses FOXO3a stability and induces its nuclear exclusion

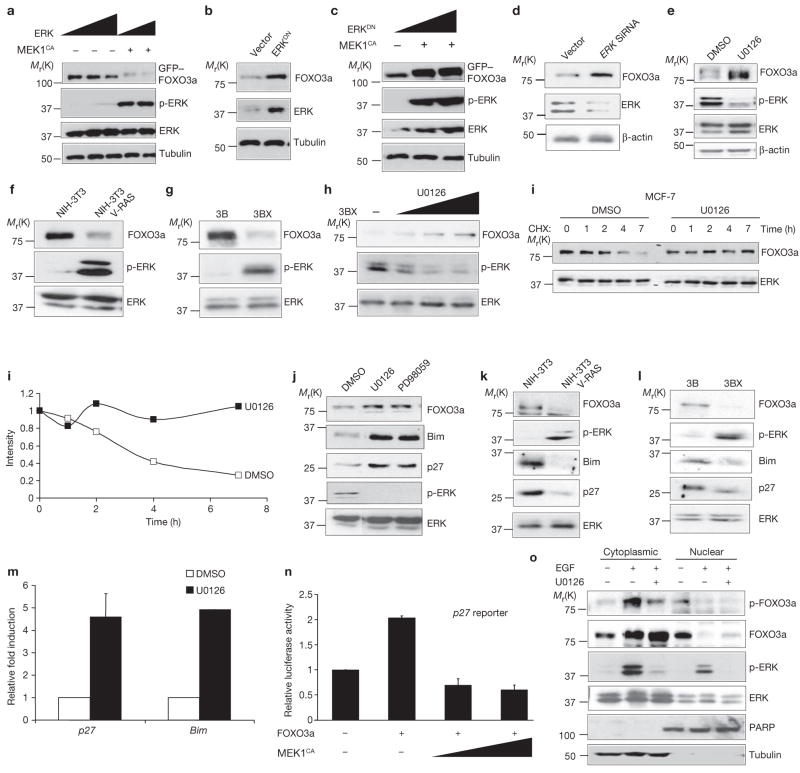

The RAS–ERK is an essential oncogenic signalling cascade that promotes tumour cell growth and development8,28. It was known that other oncogenic kinases, AKT and IKK, negatively regulate FOXO3a. In an attempt to understand the molecular mechanisms that trigger cell growth and tumour development, we asked whether ERK could regulate FOXO3a expression. When a constitutively active MEK1 (MEK1CA) that activated ERK was transfected into 293 cells, the total FOXO3a protein was reduced (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, dominant-negative ERK (ERKDN) rescued FOXO3a expression suppressed by MEK1CA (Fig. 1b, c). Similarly, using Erk small interference RNA (siRNA) to knockdown ERK protein expression level in HeLa cells (Fig. 1d), or treatment with U0126, a MEK1 inhibitor (Fig. 1e) led to a dose-dependent increase in FOXO3a protein expression (see Supplementary Information, Fig. S1a). At the same time, FOXO3a RNA levels were only slightly increased in response to U0126 (see Supplementary Information, Fig. S1b). Taken together, the results indicate that ERK mainly downregulates FOXO3a protein expression.

Figure 1.

ERk suppresses FOXO3a stability and induces its nuclear exclusion. (a–d) Lysates of 293T cells were subjected to immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies after being transfected with ERk2 and MEk1CA (a), control vector or ERkDN (b), ERk2DN and MEk1CA (c), and control vector and ERK1 and ERK2 siRNA (d). (e–h) Lysates of the following cells were analysed by direct immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies: MDA-MB-453 cells were treated with DMSO or U0126 (2 μM) for 4 h (e), NIH3T3 cells and NIH3T3 RAS-transformed cells (f), Hep-3B and Hep-3BX (g), and Hep-3BX (h) cells were treated with increasing dosages of U0126. (i) MCF-7 cells were extracted at the indicated times after CHX (1 μg ml−1) incubation before treatment with either DMSO (control) or U0126. (j–l) Lysates of MCF-7 cells (j) treated with (DMSO, U0126, or PD98059 (20 μM), NIH3T3 and NIH3T3 VRAS-transformed cells (k), and Hep-3B and Hep-3BX cells (l) were subjected to immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (m) Real-time PCR transcript of p27Kip1 and Bim were measured, and the relative fold of induction was calculated and compared between DMSO or U0126 treated cells. (n) Lysates of 293T cells cotransfected with control vectors were subjected to luciferase assays with a p27 promoter-driven luciferase reporter. In m and n, representative results s.d. from three experiments (n = 3) conducted in duplicates are shown. (o) Hep-3B cells were serum starved and then treated with EGF (50 ng ml−1) for 30 min in the presence (+) or absence (−) of U0126. Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were then analysed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. Equal amount of lysates was loaded in each lane. Similar results were also obtained by using MCF-7 cells (data not shown). Uncropped images of the scans in a, h, i and k are shown in the Supplementary Information, Fig. S5.

To validate the observation that ERK mediated the downregulation of FOXO3a, two cell lines with elevated ERK activities were used29, NIH3T3-V12Ras and Hep-3BX (a human hepatoma-derived cell line). Both cell lines showed pronounced decrease of FOXO3a protein compared to the wild-type parental cell lines (Fig. 1f, g), and treatment with U0126 increased FOXO3a protein levels in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1h). Similarly, a reduction in FOXO3a expression was observed with both EGF and 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA) treatment, both of which activate ERK. The increased FOXO3a expression was restored by inhibition of ERK activity (see Supplementary Information, Fig. S1c, d). To determine whether the ERK-mediated downregulation of FOXO3a protein expression was due to effects on FOXO3a stability, the half-life of FOXO3a protein was examined when treated with U0126. FOXO3a protein levels were significantly reduced after approximately 2 h, but remained stable for 7 h when treated with the the MEK inhibitor, U0126 (Fig. 1i). Moreover, the half-life of FOXO3a was approximately 6 h in 293 cells, as determined by 35S-methionine pulse-chase labelling experiments. However, in the presence of U0126, FOXO3a lasted more than 8 h (see Supplementary Information, Fig. S1e). The data indicate that ERK regulates FOXO3a by reducing FOXO3a stability.

To determine whether this regulation could exert an effect on downstream targets of FOXO3a (such as p27kip1 and Bim), expression levels were measured and FOXO3a, p27kip1 and Bim proteins were shown to be increased in cells treated with MEK1 inhibitors, U0126 or PD98059 (Fig. 1j), whereas levels of these proteins were suppressed in the ERK-activated NIH3T3-V12Ras and Hep-3BX cell lines compared to the parental cells lines (Fig. 1k, l). Furthermore, both Bim and p27kip1 RNAs, known to be transcriptionally regulated by FOXO3a, were increased in the presence of U0126, as shown by real time RT–PCR (Fig. 1m). MEK1CA expression significantly inhibited p27 promoter-driven luciferase reporter expression (Fig. 1n), as well as FOXO3a-dependent transcriptional activation of pGL2–6xBDB (a luciferase reporter containing FOXO-responsive elements) in a dose-dependent manner (see Supplementary Information, Fig. S1f). Taken together, the results suggest that ERK inhibits p27kip1 and Bim transcription by downregulating FOXO3a.

It is known that AKT and IKK oncogenic kinases regulate FOXO3a nuclear exportation through direct phosphorylation at Ser 253 and Ser 644, respectively17,30. We asked whether phosphorylation of FOXO3a by ERK could also lead to nuclear exclusion. To this end, nuclear and cytoplasmic fractionation was performed to determine whether FOXO3a subcellular distribution was regulated by ERK (Fig. 1o). ERK activation was induced by treatment with EGF for 30 min, either in the presence or absence of MEK1 inhibitor, U0126. FOXO3a levels were reduced in the nucleus but increased in the cytoplasm with EGF treatment, suggesting that FOXO3a was translocated from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. As expected, p-FOXO3a was increased in the cytoplasm with ERK activation and decreased with ERK inhibition (Fig. 1o). Non-phosphorylated FOXO3a levels were also slightly increased in the nucleus after 30 min treatment with U0126 (Fig. 1o), and the increase became more obvious with a 2 h U0126 treatment (see Supplementary Information, Fig. S2e). Taken together, the results suggest ERK-phosphorylated FOXO3a may translocate from nucleus to cytoplasm and lose its transcriptional activity.

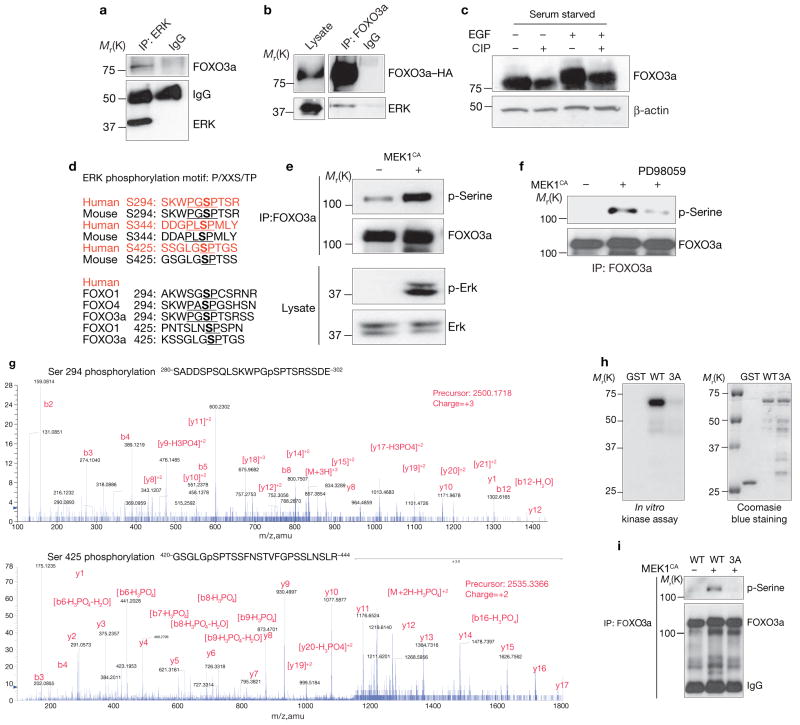

ERK interacts with and phosphorylates FOXO3a predominantly on Ser 294, Ser 344 and Ser 425

To explore the mechanism of ERK-mediated FOXO3a downregulation, the interaction between ERK and FOXO3a was characterized. Both endogenous and exogenous FOXO3a physically associated with endogenous and exogenous ERK (Fig. 2a, b). Immunoblot probing of FOXO3a revealed a remarkable band shift 10 min after treatment with EGF, which then shifted back to basal levels after 4 h. This band-shifted pattern correlated with p-ERK (see Supplementary Information, Fig. S2f) and was blocked by U0126 (see Supplementary Information, Fig. S2g), suggesting that FOXO3a was post-translationally modified in the presence of p-ERK. The FOXO3a band shift after EGF stimulation also shifted back to basal line after treatment with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIP), further indicating that the post-translational modification of FOXO3a was due to phosphorylation, presumably by p-ERK (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2.

ERk interacts with and phosphorylates FOXO3a in vitro and in vivo. (a) Lysates of MCF-7 cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting with anti-ERk and anti-FOXO3 antibodies, respectively. (b) Lysates of 293T cells transfected with FOXO3a–HA and ERk were subjected to immunoprecipitation with an anti-HA antibody and immunoblotting with an anti-ERk antibody. (c) The lysates from MCF-7 cells serum starved overnight and stimulated with EGF for 30 min were treated with CIP and subjected to immunoblotting. (d) The putative ERk consensus sequences for phosphorylation on FOXO3a were: P, proline; S, serine; T, threonine; and X, any amino acid. (e) Lysates of 293T cells transfected with GFP–FOXO3a and control or MEk1CA plasmids were subjected to immunoprecipitation with an anti-FOXO3a antibody and immunoblotting with an anti-phospho-serine antibody or direct immunoblotting with either an anti-p-ERk or an anti-ERk antibody. (f) Cells treated with PD98059 for 4 h before the lysates were extracted and subjected to analysis as described in e. (g) Lysates from MCF-7 cells that had been serum starved overnight and stimulated with EGF for 30 min were subjected to immunoprecipitation with an anti-FOXO3a antibody, and the isolated FOXO3a bands were subjected to mass spectrometry. (h) In vitro kinase assays were conducted by incubating recombinant activated ERk2 with GST–FOXO3a (281–673) and mutant GST–FOXO3a3A proteins. (i) Lysates of 293T cells cotransfected with FOXO3a or mutant FOXO3a3A and MEk1CA were subjected to immunoprecipitation with an anti-FOXO3a antibody and immunoblotting with an anti-phospho-serine antibody. An uncropped image of the blot is shown in the Supplementary Information, Fig. S5

To further determine whether ERK could directly phosphorylate FOXO3a, an in vitro kinase assay was performed, and revealed that full-length FOXO3a–GST fusion proteins were phosphorylated by recombinant-activated ERK proteins directly (see Supplementary Information, Fig. S2h). By isolating phosphorylated FOXO3a from the in vitro kinase assay (data not shown) and analysing it by mass spectrometry, three ERK-specific phosphorylation sites were identified in FOXO3a: Ser 294, Ser 344 and Ser 425. A BLAST search of the National Center for Biotechnology Information database revealed that Ser 294, Ser 344 and Ser 425 of FOXO3a are common residues in other FOXO subfamily members, and are conserved in both humans and mice (Fig. 2d).

To confirm that all three of these ERK-specific phosphorylation sites existed in FOXO3a in vivo, an anti-phospho-serine antibody was used to detect serine-phosphorylated FOXO3a in MEK1CA-transfected cells (Fig. 2e). The serine phosphorylation of FOXO3a was abolished by MEK1 inhibitor (PD98059) treatment (Fig. 2f). Phosphorylation of Ser 294 and Ser 425 was identified by in vivo mass spectrometry from MCF-7-cell extracts (Fig. 2g). Phosphorylation of Ser 344 was not detected in the mass spectrometry analysis, but was confirmed using a newly developed antibody that can recognize phospho-Ser 344 of FOXO3a, and the phosphorylated FOXO3a was mainly located in the cytoplasm when p-ERK was activated by EGF treatment (Fig. 1o and see Supplementary Information, Fig. S2a–c). The original intention was to generate phospho-specific antibodies against all three phospho-serine peptides of FOXO3a. However, only two phospho-specific antibodies were successful, those against p-Ser 344 and p-Ser 425 (see Supplementary Information, Fig. S2d). These two phospho-specific antibodies were further used to demonstrate that MEK1CA stimulates phosphorylation of Ser 344 and Ser 425 (see Supplementary Information, Fig. S2d).

FOXO3a3A, a mutant in which all three serine residues were substituted for alanine residues to mimic a non-phosphorylated status, was resistant to phosphorylation by ERK in kinase assays in vitro compared with wild-type FOXO3a (Fig. 2h). Consistent with the in vitro kinase assay data, FOXO3a3A had a significantly lower serine phosphorylation levels in vivo than wild-type FOXO3a (Fig. 2i). Taken together, the data support that the three serine residues are specific phosphorylation sites for ERK.

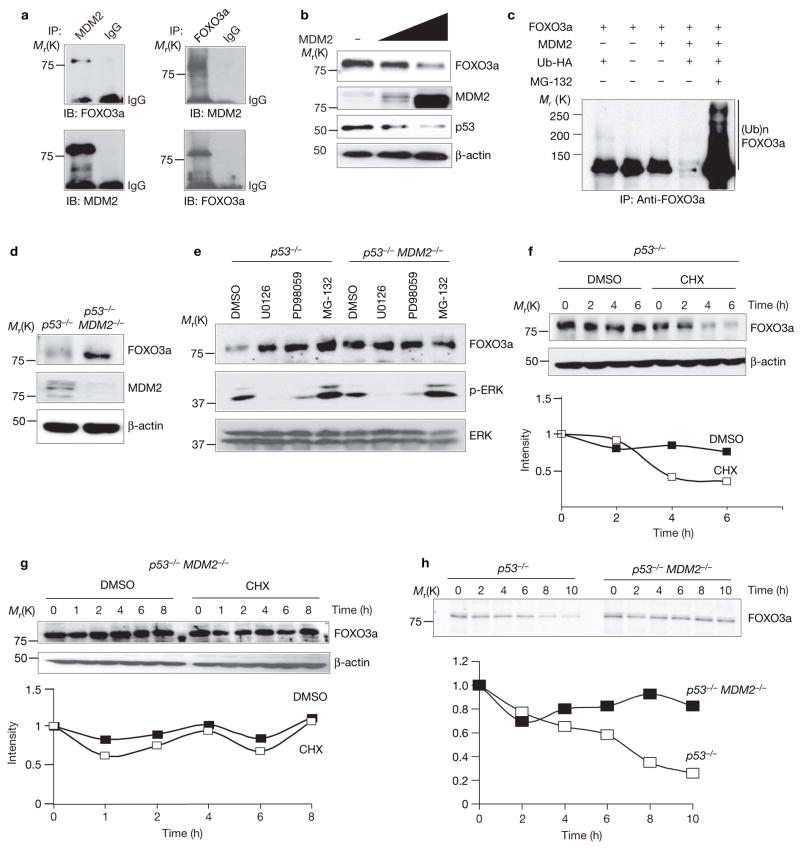

MDM2 is required for ERK-mediated FOXO3a degradation

As the RAS–ERK pathway was known to upregulate MDM2 protein expression26,27, and ERK was shown to downregulate FOXO3a protein expression and stability in our experiments (Fig. 1a–h and i), we further asked whether MDM2 might be involved in the ERK-mediated FOXO3a downregulation. First, endogenous MDM2 was shown to associate with FOXO3a in MCF-7 cells by reciprocal immunoprecipitation (Fig. 3a). MDM2 also reduced endogenous FOXO3a protein levels in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3b) and the reduced FOXO3a levels were recovered when treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 (Fig. 3c), which suggests that FOXO3a stability was regulated through proteasome degradation. In addition, a FOXO3a protein gel exhibited a polyubiquitination pattern when ubiquitin was coexpressed, suggesting that FOXO3a was subjected to polyubiquitin modification and further proteasomal degradation (Fig. 3c). Consistently, p53−/−MDM2−/− double-knockout MEFs showed more stabilized FOXO3a expression compared with p53−/− MEF cells (Fig. 3d). Taken together, these results indicate that MDM2 associates with FOXO3a and may function as an ubiquitin ligase for FOXO3a proteasomal degradation.

Figure 3.

MDM2 is required for ERk-mediated FOXO3a degradation. (a) MCF-7 cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with an anti-MDM2 antibody and immunoblotting with an anti-FOXO3a antibody. (b) Lysates of 293T cells transfected with MDM2 at different dosages and subjected to immunoblotting. (c) Lysates of cotransfected cells treated with the indicated vectors in the presence of MG-132 (20 μM, 4 h) were subjected to immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting with an anti-FOXO3a antibody. (d) Lysates of p53−/− or p53−/−MDM−/− MEFs were subjected to immunoblotting using different antibodies, as indicated. (e) MEFs were treated with different inhibitors and analysed by immunoblotting. (f, g) MEFs were treated with or without CHX, harvested at the indicated times and subjected to immunoblotting. (h) MEFs were treated with methionine and cysteine-free medium overnight, pulsed with 35S-Met-Cys for 30 min, and chased for the indicated times. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-FOXO3a antibody and subjected to SDS–PAGE, gels were fixed, dried,and subjected to autoradiography (with an intensifying screen). An uncropped image of the blot in e is shown in the Supplementary Information, Fig. S5.

To further determine the pathological relevance of the relationship between MDM2 and FOXO3a expression, we examined whether the expression of MDM2 might be inversely correlated with FOXO3a expression in human breast cancer tissues. A significant correlation between the MDM2-positive and FOXO3a-negative tissues was found in a cohort of 125 breast cancer patients (Table 1). Representative tumours from consecutive sections of six different patients stained with FOXO3a and MDM2 are shown in the Supplementary Information, Fig. S3a. To support the reliability of immunohistochemical staining, fourteen freshly prepared human breast tumour lysates were immunoblotted. Both the immunohistochemical staining and immunoblotting showed a reverse correlation between FOXO3a and MDM2 expression (see Supplementary Information Fig. S3b). In addition, the MDM2-positive and FOXO3a-negative expression pattern was also significantly associated with higher tumour grade (Table 2). Thus, MDM2-mediated downregulation of FOXO3a may play a role in the development of human breast cancer.

Table 1.

Inverse correlation between MDM2 and FOXO3a expression in human breast cancer tissues

| FOXO3a | MDM2 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| − | + | ||

| − | 17 (21.6) | 61 (48.8) | 78 (62.4) |

| + | 20 (16.0) | 27 (13.6) | 47 (37.6) |

| Total (percentage) | 37 (29.6) | 88 (70.4) | 125 (100) |

The 125 surgical breast cancer tumour specimens were analysed by immunohistochemical staining antibodies specific to FOXO3a and MDM2, respectively. The expression pattern of FOXO3a and MDM2 was analysed by using χ-square test (P = 0.0138). A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Table 2.

MDM2+ and FOXO3a− is associated with higher tumour grade in breast cancer patients.

| Combined | Tumour grade | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||

| MDM2− FOXO3a− | 0 (0.0) | 17 (16.50) | 17 |

| MDM2+ FOXO3a− | 9 (40.91) | 52 (50.49) | 61 |

| MDM2− FOXO3a+ | 7 (31.82) | 13 (12.62) | 20 |

| MDM2+ FOXO3a+ | 6 (27.27) | 21 (20.39) | 27 |

| Total | 22 | 103 | 125 |

The relationship between combined expression of FOXO3a and MDM2 and tumour grade in human breast cancer specimens was analysed using a χ-square test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

We then asked whether MDM2 was required for ERK-mediated FOXO3a donwnregulation. In p53−/− MEFs, FOXO3a protein levels were stabilized by MEK1 inhibitors (U0126, PD98059), which stabilized FOXO3a level similar to the extent as the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 (Fig. 3e). Examining the cell line, p53−/−MDM2−/− MEFs, showed that FOXO3a protein levels were not affected by ERK inhibition in the absence of MDM2 (Fig. 3e), which further indicated that ERK regulation of FOXO3a stability is MDM2 dependent. FOXO3a half-life was further examined by employing the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) and with pulse-chase experiments using 35S-methionine labelling. In p53−/− MEFs, FOXO3a protein levels decrease 50% after 4 h treatment with CHX and, consistently, in pulse-chase experiments, FOXO3a protein levels were also decreased 50% in approximately 6 h (Fig. 3f, h). However, in p53−/−MDM2−/− MEFs, FOXO3a expression remained constant, even after 8 h CHX treatment and 10 h 35S-methionine labelling analysis (Fig. 3g, h), indicating that MDM2 is required for downregulation of FOXO3a. Taken together, the results suggest that MDM2 mediates ERK-mediated FOXO3a degradation.

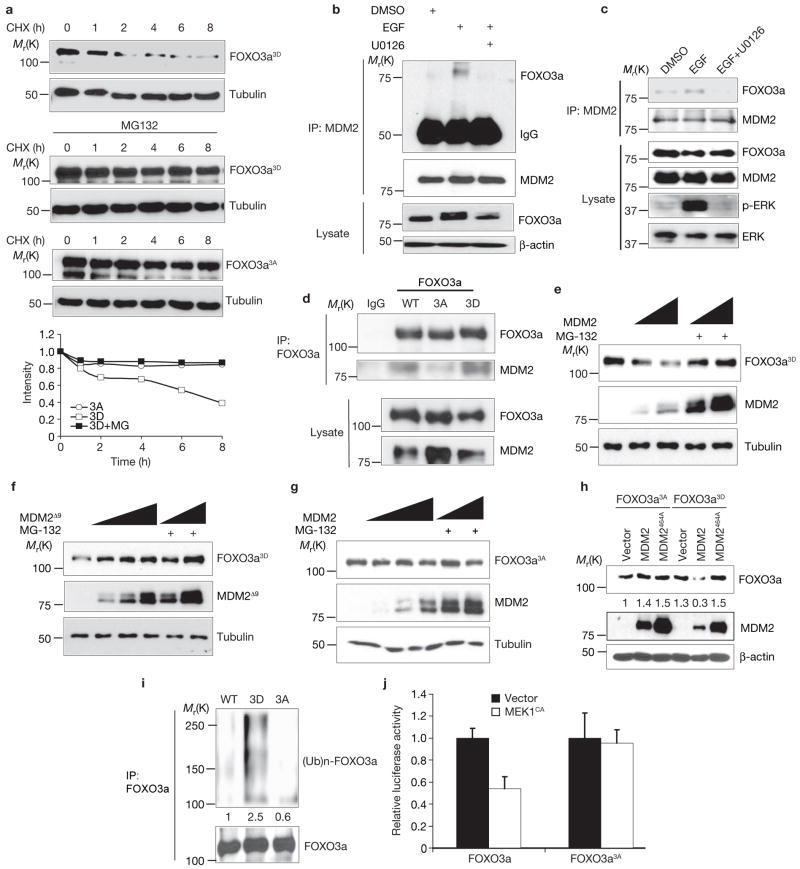

MDM2 degrades FOXO3a3D via the ubiquitin-proteasome degradation pathway

To further support the evidence that the ERK-mediated phosphorylation of FOXO3a alters its stability, the stability of two mutant proteins was compared: FOXO3a3A, a non-phosphorylation-mimic mutant, and FOXO3a3D, a phosphorylation-mimic mutant. FOXO3a3D levels decreased after 2 h CHX treatment and the downregulation was rescued by the addition of MG-132 (Fig. 4a). In comparison, FOXO3a3A levels remained unchanged in the presence of CHX for more than 8 h (Fig. 4a), and were similar to the levels in FOXO3a3D-expressing cells that had been treated with MG-132 (Fig. 4a). Together with the data shown in Fig. 1i, the results suggest that phosphoryaltion of FOXO3a by ERK regulates FOXO3a protein stability.

Figure 4.

Phosphorylation of FOXO3a by ERk facilitates MDM2-mediated FOXO3a degradation through an ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. (a) Lysates of 293T cells transfected with GFP–FOXO3a3A or GFP–FOXO3a3D harvested at different time points after treated with CHX or MG-132 were analysed by immunoblotting. (b) Lysates of MCF-7 cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting under different conditions. (c, d) Lysates of 293T cells transfected with wild-type (WT) FOXO3a (c) and 293T cells transfected with wild-type FOXO3a or mutants FOXO3a3A and FOXO3a3D (d) were subjected to immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting. (e–g) Lysates of 293T cells cotransfected with FOXO3a3D (e) or FOXO3a3A (g), together with different dosages of wild-type MDM2 or deletion mutant of MDM2, MDM2Δ9 (f), with or without MG-132, were analysed by immunoblotting. (h) Lysates of 293T cells cotransfected with FOXO3a3A or FOXO3a3D, together with wild-type MDM2 or mutant MDM2464A were subjected to immunoblotting. (i) Lysates of 293T cells cotransfected with wild-type FOXO3a, FOXO3a3D or FOXO3a3A, together with MDM2 and ubiquitin in the presence of MG-132, were analysed by immunoblotting. (j) Lysates of 293T cells cotransfected with 6XDBE–Luc and pRL-Tk, and FOXO3a or FOXO3a3A, together with control vector or MEk1CA were subjected to luciferase assay. The results were from three experiments (n = 3) with the error bars representing s.d. from duplicates in each case. Uncropped images of the blots in e–g are shown in the Supplementary Information, Fig. S6.

Next, we examined the role of ERK in MDM2-mediated FOXO3a degradation. To determine whether ERK status affects the association between MDM2 and FOXO3a, the association between endogenous and exogenous MDM2 and FOXO3a was examined, and was enhanced in EGF-stimulated cells, but was reduced with U0126 treatment (Fig. 4b, c). Consistently, the FOXO3a3D mutant mimicking ERK-phosphorylated FOXO3a interacted more strongly with MDM2 than the FOXO3a3A mutant mimicking non-phosphorylated FOXO3a (Fig. 4d). These results suggest that ERK-induced phosphorylation of FOXO3a mediates MDM2-dependent degradation and may serve as a docking site for MDM2 to bind with and ubiquitinate FOXO3a for further degradation.

To determine whether the interaction between p-FOXO3a and MDM2 promotes FOXO3a degradation, FOXO3a3D and MDM2 were cotransfected in 293T cells. As expected, FOXO3a3D levels were inversely correlated with MDM2 protein levels, and MG-132 treatment stabilized FOXO3a3D levels (Fig. 4e). FOXO3a3D levels remained unchanged in the presence of either MDM2Δ9 or MDM2464A mutants known to dramatically reduce the ubiquitin ligase activity of MDM2 (refs 31–33; Fig. 4f, h), but decreased approximately fourfold in the presence of wild-type MDM2 (Fig. 4e, h). In addition, FOXO3a3A levels were not affected by the presence of wild-type MDM2 (Fig. 4g, h) suggesting that the FOXO3a3D mutant is more susceptible to degradation by MDM2 than FOXO3a3A.

Ubiquitination of the wild-type and mutant FOXO3a was then examined. FOXO3a3D was heavily ubiquitinated, whereas FOXO3a3A was resistant to polyubiquitination (Fig. 4i). FOXO3a3A mutant was also resistant to MEK1CA-mediated inactivation of FOXO3a transcriptional activity, as measured by a luciferase reporter assay (Fig. 4j). Taken together, the data show that MDM2 may serve as an E3 ligase for FOXO3a degradation, and that the interaction between MDM2 and FOXO3a is dependent on ERK kinase activity through phosphorylating FOXO3a, thus making it more susceptible to MDM2-mediated degradation.

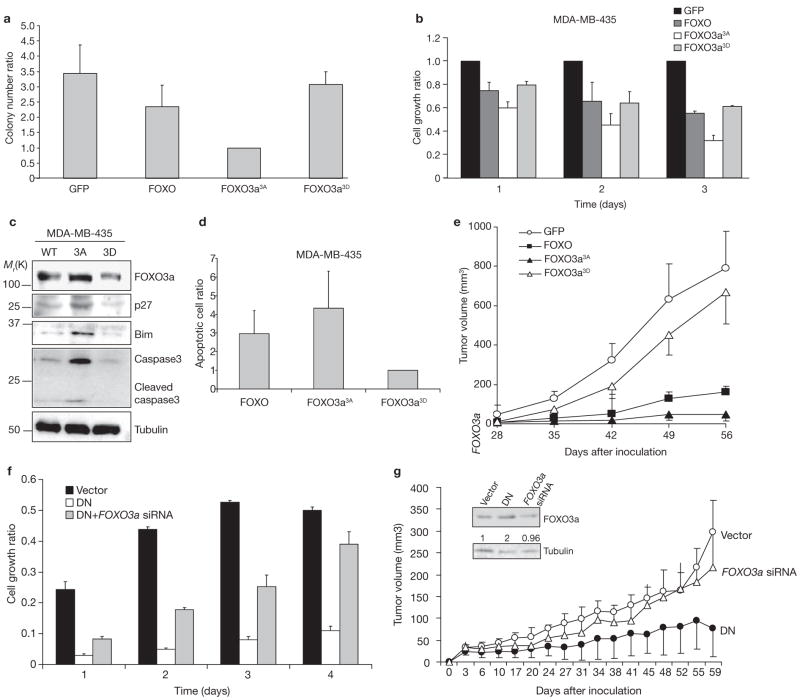

FOXO3a3A inhibits tumorigenesis and induces apoptosis

We further examined the function of FOXO3a3A and FOXO3a3D in cell transformation and tumorigenesis by introducing vector–GFP, wild-type FOXO3a–GFP, FOXO3a3A–GFP and FOXO3a3D–GFP expression vectors into MDA-MB-435 breast cancer cells. GFP-positive cells were sorted and selected for soft agar colony formation assays and MTT cell proliferation assays. Wild-type FOXO3a decreased colony formation by 23% compared to GFP alone. FOXO3a3A–GFP inhibited colony formation by 70%, whereas FOXO3a3D–GFP led to an 11% inhibition (Fig. 5a). FOXO3a3A–GFP also exhibited more potent inhibition activity in the MTT cell proliferation assays (Fig. 5b and see Supplementary Information, Fig. S4a).

Figure 5.

FOXO3a3A, but not FOXO3a3D, inhibits tumorigenesis and induces apoptosis. (a) MDA-MB-435 cells were transfected with control vector, wild-type FOXO3a, FOXO3a3A or FOXO3a3D. After sorting with GFP marker, GFP-positive cells were subjected to the colony formation and MTT assays. (b) Cells obtained as described in a were measured for cell growth rate by MTT assay. All experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3). A representative sample is shown in a and b. (c) Lysates from cells obtained as described in a and MDA-MB-435 cell lines, as indicated, were analysed by immunoblotting. (d) MDA-MB-435 cells were transfected with control vector, wild-type FOXO3a, FOXO3a3A or FOXO3a3D and, after propidium iodide (PI) staining, the cells were analysed by FACS, performed as described in the Methods. Only the GFP-positive cells were measured in the sub-G1 phase as apoptotic cells, and the apoptosis ratio was normalized with the control vector. (e) The MDA-MB-435-transfected cell lines were sorted for GFP-positive cells, which then were injected into the mammary fat pads of nude mice. (f) MDA-MB-435 cells were transfected with control vector, ERk1DN and ERk2DN (DN), and ERk1DN, ERk2DN and FOXO3a siRNA, and the cells were subjected to MTT assays. (g) Cells (2 × 106) cells obtained as described in f were injected into the mammary fat pads of nude mice. The tumour volume was measured twice per week. The inset shows FOXO3a expression quantified by normalization with tubulin expression. An uncroppped image of the blot in c is shown in the Supplementary Information, Fig. S6.

Notably, p27, Bim and cleaved-caspase3 proteins were upregulated in FOXO3a3A cells, but not in FOXO3a3D cells (Fig. 5c), suggesting that cell-cycle regulation and apoptosis contribute to the anti-proliferative activity of FOXO3a3A (Fig 5c). As shown in Fig. 5d, cells transfected with FOXO3a3A–GFP exhibitd fourfold more apoptosis than those transfected with FOXO3a3D–GFP. To further test the tumour suppression activity in vivo, GFP-positive cells were inoculated into the mammary fat pads of nude mice, which were then monitored for tumour development (Fig. 5e). FOXO3a3A inhibited tumour growth, whereas the FOXO3a3D mutant had no tumour-suppression activity. Our results suggest that non-phosphorylated form of FOXO3a is a stronger suppressor of tumorigenesis than its phosphorylated counterpart, and that the phosphorylation and downregulation of FOXO3a facilitate its tumour suppression activity.

To further determine whether ERK promotes tumorigenesis through downregulation of FOXO3a, MDA-MB-435 breast cancer cells were transfected with ERKDN or ERKDN along with FOXO3a siRNA. In MTT assays, ERKDN reduced breast cancer cell growth, which was restored by treatment with FOXO3a siRNA (Fig. 5f). The FOXO3a siRNA result was validated by rescuing its effects with FOXO3a overexpression (see Supplementary Information, Fig. S4b, 4c). Furthermore, ERKDN strongly inhibited tumour growth in animals, and ERKDN-mediated tumour suppression required expression of FOXO3a, as treatment with FOXO3a siRNA reduced its tumour suppression activity (Fig. 5g). Taken together, the results suggest that ERK may enhance tumorigenecity by downregulation of FOXO3a.

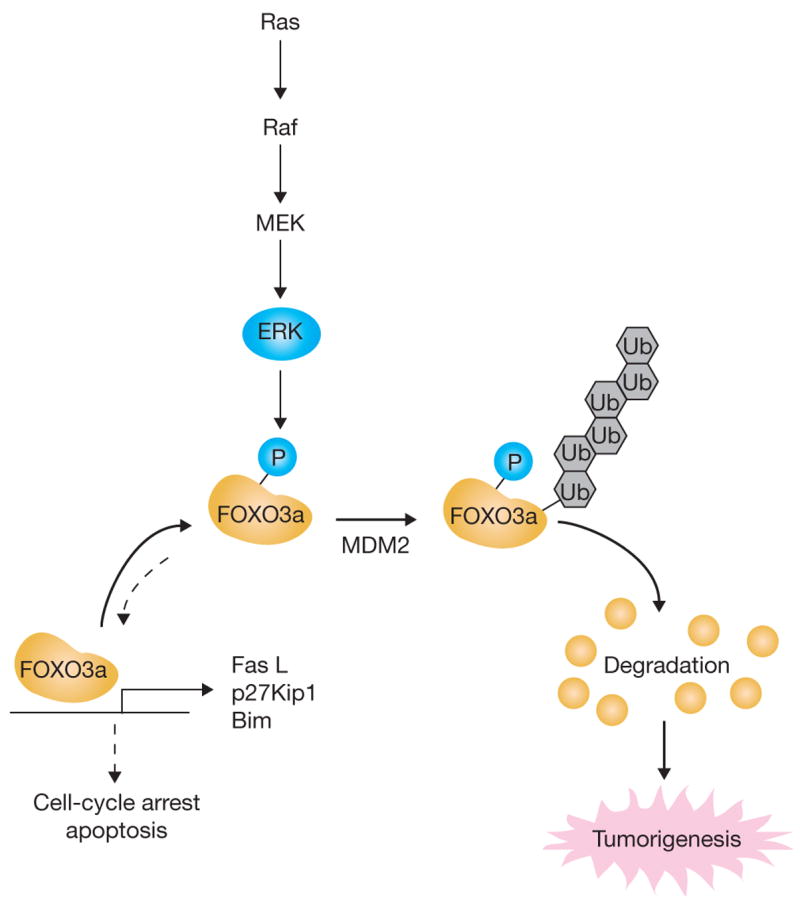

DISCUSSION

Here, we propose a novel signalling pathway: the tumour suppressor gene FOXO3a is regulated by the oncoprotein ERK through interaction and degradation by the MDM2-mediated ubiquitin-proteosome pathway (Fig. 6). We identified three FOXO3a Erk kinase phosphorylation sites (Ser 294, Ser 344 and Ser 425). Phosphorylation of these serine residues increases FOXO3a cytoplasmic distribution and susceptibility to interaction and degradation by MDM2, which serves as a bona fide E3 ligase mediating FOXO3a degradation. Moreover, the non-phosphorylated FOXO3a mutant (FOXO3a3A), which is resistant to MDM2-mediated degradation, exhibits potent inhibition of cell proliferation, induction of apoptosis and suppression of tumour growth. Our data demonstrate an essential role for ERK–MDM2-mediated FOXO3a regulation in tumorigenesis.

Figure 6.

ERk promotes tumorigenesis by inhibiting FOXO3a via MDM2-mediated degradation. Schematic representation showing that ERk interacts with and phosphorylates FOXO3a at Ser 294, Ser 344 and Ser 425; phosphorylation at these residues increases FOXO3a-MDM2 interaction and enhances FOXO3a degradation through a MDM2-dependent ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, leading to tumorigenesis.

In addition, combining our observations and the results of previous studies, three important oncogenic kinases (AKT, IKKβ and ERK) are all involved in regulating FOXO3a nuclear localization and activity through discrete phosphorylation at different sites (see Supplementary Information, Fig. S4d)17,30. Thus, inactivation of FOXO3a may represent a critical and common step in survival pathways in cancer cells. Recently, ERK and p38 were shown to phosphorylate FOXO1. However, the functional outcomes were not discussed in the study9. On the other hand, overexpression of forkhead transcription factors (AFX and FKHR-L1) was shown to cause growth suppression in RASV12-transformed cells34. Consistently, our results show that maintaining FOXO3a activity by abolishing ERK-mediated phosphorylation is sufficient to revert cell growth caused by ERK activation due to RAS mutation (see Supplementary Information, Fig. S4a), which accounts for 30% of human cancers. In addition, expression of FOXO3a was shown to inhibit tumour development in animal models17 (Fig. 5e), and repression of FOXO3a expression enhances tumour progression (Fig. 5g) and angiogenesis10,17–19. Taken together, the data suggest that enhancing FOXO3a activity may be a potential therapeutic strategy for treating human cancers.

ERK has been shown to promote cell growth and tumorigenesis3,4,6,28. ERK activation was also known to result in GSK3β inactivation and an accumulation of β-catenin in the nucleus29, where β-catenin stimulates c-Myc and cyclin D1 transcription that, in turn, facilitate cell proliferation29,35,36. Thus, targeting RAS–ERK has been considered a promising approach for inhibition of tumour proliferation and to increase the sensitivity of cancer cells to chemotherapy4,5. Several pharmacological reagents have been developed to specifically targeting RAF–MEK–ERK signalling, some of which have been approved for clinical use4,5. We propose that cancer cells acquire resistance to apoptosis and enhance cell proliferation through orchestrated inhibitions of FOXO3a and GSK3β with activated ERK, which further leads to constitutive survival signalling cascades and tumorigenesis. Furthermore, our study elucidates the possibility of increasing the therapeutic efficacy of ERK inhibitors by concurrent activation of FOXO3a.

METHODS

Reagents and plasmids

MEK1 inhibitors U0126 and PD98059 were purchased from Cell Signaling. MG-132, CHX and EGF were purchased from Sigma. The dual-luciferase assay kit was purchased from Promega. GFP–FOXO3a construct was generated in our previous study17. Mutants of GFP–FOXO3a, GFP–FOXO3a3A and GFP–FOXO3a3D, were generated using the Quick Change multi site-directed mutagenesis kit from Stratagene. MEK1CA and MDM2464A expression plasmids were gifts from P. P. Pandolfi (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) and D.-H. Yan (UTMDACC, Houston, TX). MDM2 and the MDM2 deletion mutant were from gifs from J. Chen (H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL); the reporter plasmids p27–Luc and pGL2–6xDBE were gifts from T. Sakai (Kyoto Prefectual University of Medicine, Japan) and P. Coffer (University Medical Center, Utrecht, The Netherlands), and the pSuper–FOXO3a siRNA vector was a gift from A. Toker (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA)37.

Immunochemistry, in vivo ubiquitination and GST pulldown assays

Immunohistochemical staining, immunoblotting, immunoprecipitation and in vivo ubiquitination were performed, as previously described25, with the following antibodies: FOXO3a, MDM2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), ERK (Upstate Biotechnology), p-ERK, p-serine (Cell Signaling), p27, p38, JNK1 (BD Biosciences) and Bim (Stressgen). For GST pulldown assays, GST–FOXO3a protein (10 μg) was incubated at 4 °C with 5 mg MCF-7 cell-extract overnight, and the GST-tagged proteins were recovered by incubating the reaction at 4 °C for 3 h with 20 μl glutathione–Sepharose 4B beads. The bead pellet was washed three times with 1 ml buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl at pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100 and 2 mM EDTA). Boiled samples were then subjected to 8% SDS–PAGE.

Real-time PCR

Forward and reverse primer sequences were: Bim, 5′-AACCTTCTGATGTAAGTTCT-3′ and 5′-GTGATTGCCTTCAGGATTAC-3′; p27, 5′-GTGCGAGTGTCTAACGGGAG-3′ and 5′-GTTTGACGTCTTCTGAGGCC-3′; FOXO3a, 5′-GCTGTCTCCATGGACAATAG-3′ and 5′-GCTGGCTTGTTCTCTTGGAT-3.

In vitro kinase and in vivo 35S-methionine labelling assays

Purified GST–FOXO3a protein was incubated with active ERK2 (Upstate Biotechnology) in the presence of 50 mM ATP in a kinase buffer containing 5 μCi γ-32P-ATP for 30 min at 30 °C. Reaction products were resolved by SDS–PAGE, and products labelled with 32P were visualized by autoradiography. The in vivo 35S-methionine labelling was performed as previously described25.

In-gel protein digestion

A slightly modified version of a previously published protocol was used38. Briefly, pieces of interest from the silver-stained gel were washed with 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate and ACN, reduced with DTT at 60 °C for 40 min and alkylated by IAA in the dark for 30 min. The gel pieces were washed twice with 50 μl 50% ACN and 50% 200 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer (pH 8.0) for 5 min, dehydrated in 50 μl 100% ACN until the gel turned opaque white, and dried in a vacuum centrifuge for 30 min. The gel pieces were rehydrated in 5–10 μl 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate at 37 °C for 4 min. An equivalent volume (10–35 μl) of trypsin (Promega) solution (10 ng μl−1 in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate) was added until the gel pieces were fully immersed. After digestion at 30 °C overnight, the supernatants were transferred into new microtubules for IMAC purification.

Nanoelectrospray mass spectrometry

A nanoscale capillary LC-MS/MS analysis was performed by using an Ultimate capillary LC system (LC Packings) coupled to a QSTARXL quadrupole (Q)–time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems), as previously described39. The nanoscale capillary LC separation was performed on an RP C18 column (15 cm × 75 m i.d.) with a flow rate of 200 nl min−1 and a 70-minutelinear gradient of 5–50% buffer B. Buffer A contained 0.1% formic acid in 2% aqueous ACN, and buffer B contained 0.1% formic acid in 98% aqueous ACN. The nanoscale capillary LC tip used for online LC-MS was a PicoTip (FS360-20-10-D-20; New Objective). Data was acquired using an automatic information-dependent acquisition system (Applied Biosystems), which locates the most intense ions in a TOF MS spectrum and performs an optimized MS/MS analysis on the selected ions. The product ion spectra generated by nanoscale capillary LC-MS/MS were searched against National Center for Biotechnology Information databases for exact matches using the ProID (Applied Biosystems) and MASCOT search programs40. A Homo sapiens taxonomy restriction was used, and the mass tolerance of both precursor ions and fragment ions was set to ± 0.3 Da. Carbamidomethyl cysteine was set as a fixed modification, and serine, threonine and tyrosine phosphorylation were set as variable modifications. All phosphopeptides identified were confirmed by manual interpretation of the spectra.

CIP treatment

The cell lysate was harvested, followed by incubation with 1 μl 10 U μl−1 CIP (New England Biolabs) in 50 μl CIP buffer for 1 h at 37 °C. Reactions were stopped by two washes in CIP buffer and boiling in gel-loading buffer.

Cell culture, cell growth, soft agar assay and FACS analysis

All cell cultures were kept in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS at 5% CO2 and the concentrations and time for each chemical treatment were as following: U0126 (5 μM, 4 h), PD98059 (20 μM, 4 h), MG-132 (20 μM, 6 h), CHX (1 μg ml−1) and EGF (100 ng ml−1). The cell growth rate was determined by MTT assay. Cells (3 × 103 per well) were plated in 96-well culture plates. After cells adhered, 20 μMTT was added and incubated for 2 h before 100 μl lysis buffer (20% SDS in 50% N,N-dimethylformamide at pH 4.7) was added. After incubating, absorbance was measured at 570 nm. For the soft agar transformation assay, 5 × 104 cells were placed in 1.5 ml DMEM with 10% FBS and 0.3% agarose and overlaid onto 3 ml DMEM with 10% FBS and 0.6% agarose in each well of a six-well plate. After 2–3 weeks, colonies larger than 2 mm in diameter were counted. For the FACS analysis, cells were trypsinized and fixed in 70% ice-cold ethanol overnight. Cells were then incubated with 1 ml propidium iodide solution (Sigma; 50 μg ml−1 in PBS) plus 25μg ml−1 RNase for 30 min at 37 °C and measured.

Animal studies

Tumorigenesis assays were performed in an orthotopic breast cancer mouse model41. MDA-MB-435 breast cancer cells were transfected by liposome or electroporation (Amaxa Inc.). GFP-positive cells were selected by cell sorting. Cells (2 × 106) were injected into the mammary fat pads of nude mice (n = 10 per group). The remaining cells were used for soft agar assays and immunoblotting against FOXO3a, p27Kip1, Bim and caspase 3. Tumour size was measured weekly with a caliper, and tumour volume was determined using the formula: l × w2 × 0.52, where l is the longest diameter and w is the shortest diameter.

Statistical analysis

SAS software (version 8.1) was used for statistical analysis (SAS Institute). A univariate analysis was used to determine the variable distributions. Categorical variables among the groups were compared with the χ-squared test or Fisher’s exact test if 20% of the expected values were smaller than five. Continuous variables were analysed using the two-tailed Student’s t-test. Linear regression analysis was used to analyse the FOXO3a and MDM2 expression in the lysates of breast cancer patients. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Note: Supplementary Information is available on the Nature Cell Biology website.

Acknowledgments

P. P. Pandolfi, D.-H. Yan, J. Chen, T. Sakai, P. Coffer and A. Toker for providing expression plasmids; G. Lozano for the knockout MEF cells; M. C.-H. Hu for the p-FOXO3a (644) antibodies; Y. Wei, J.-M. Hsu, S. Zhang, J.-F. Lee and C.-T. Chen for technical support; W. Kaelin, M. Van Dyke and D. Sarbasov for critical comments on the manuscript; and J. C. Cheng and the Department of Scientific Publications, M. D. Anderson Cancer Center for editing the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant P01 CA 099031, MDACC SPORE in Breast Cancer CA116199 and The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center support grant CA16672, and was partially supported by the National Breast Cancer Foundation, Inc., Patel Memorial Breast Cancer Research Foundation, Breast Cancer Research Foundation grant and Kadoorie Charitable Foundations.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS: J.-Y.Y. and M.-C.H. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. M.-C.H. supervised the research. J.-Y.Y. and C.S.Z. performed most of the experiments. W.X. performed the immunohistochemistry staining and contributed to the results shown in Tables 1 and 2. X.X. and J.-Y.L. performed the animal experiments. H.Y., Q.D., C.-J.C., W.-C.W., H.-P.K., D.-F.L., L.-Y.L., H.-C.L. and X.C. assisted with experiments for the revision of the manuscript. C.-C.L., F.-J.T. and C.-H.T were responsible for the LC-MC/MS data. H.H. performed the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to discussions of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Cancer genes and the pathways they control. Nature Med. 2004;10:789–799. doi: 10.1038/nm1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoon S, Seger R. The extracellular signal-regulated kinase: multiple substrates regulate diverse cellular functions. Growth Factors. 2006;24:21–44. doi: 10.1080/02699050500284218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kolch W. Coordinating ERK/MAPK signalling through scaffolds and inhibitors. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:827–837. doi: 10.1038/nrm1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson N, Lyons J. Recent progress in targeting the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway with inhibitors in cancer drug discovery. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2005;5:350–356. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scholl FA, Dumesic PA, Khavari PA. Effects of active MEK1 expression in vivo. Cancer Lett. 2005;230:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinberg RA. Fas oncogenes and the molecular mechanisms of carcinogenesis. Blood. 1984;64:1143–1145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giehl K. Oncogenic Ras in tumour progression and metastasis. Biol Chem. 2005;386:193–205. doi: 10.1515/BC.2005.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asada S, et al. Mitogen-activated protein kinases, Erk and p38, phosphorylate and regulate Foxo1. Cell Signal. 2007;19:519–527. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greer EL, Brunet A. FOXO transcription factors at the interface between longevity and tumor suppression. Oncogene. 2005;24:7410–7425. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finnberg N, El-Deiry WS. Activating FOXO3a, NF-kappaB and p53 by targeting IKKS: an effective multi-faceted targeting of the tumor-cell phenotype? Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3:614–616. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.7.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burgering BM, Kops GJ. Cell cycle and death control: long live Forkheads. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:352–360. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tran H, Brunet A, Griffith EC, Greenberg ME. The many forks in FOXO’s road. Sci STKE RE5. 2003 doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.172.re5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dijkers PF, et al. Forkhead transcription factor FkHR-L1 modulates cytokine-dependent transcriptional regulation of p27(kIP1) Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:9138–9148. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.24.9138-9148.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt M, et al. Cell cycle inhibition by FoxO forkhead transcription factors involves downregulation of cyclin D. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7842–7852. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.22.7842-7852.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang JY, Xia W, Hu MC. Ionizing radiation activates expression of FOXO3a, Fas ligand, and Bim, and induces cell apoptosis. Int J Oncol. 2006;29:643–648. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu MC, et al. IkappaB kinase promotes tumorigenesis through inhibition of forkhead FOXO3a. Cell. 2004;117:225–237. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00302-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu MC, Hung MC. Role of IkappaB kinase in tumorigenesis. Future Oncol. 2005;1:67–78. doi: 10.1517/14796694.1.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Potente M, et al. Involvement of Foxo transcription factors in angiogenesis and post-natal neovascularization. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2382–2392. doi: 10.1172/JCI23126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paik JH, et al. FoxOs are lineage-restricted redundant tumor suppressors and regulate endothelial cell homeostasis. Cell. 2007;128:309–323. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plas DR, Thompson CB. Akt activation promotes degradation of tuberin and FOXO3a via the proteasome. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:12361–12366. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bond GL, Hu W, Levine AJ. MDM2 is a central node in the p53 pathway: 12 years and counting. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2005;5:3–8. doi: 10.2174/1568009053332627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou BP, et al. HER-2/neu induces p53 ubiquitination via Akt-mediated MDM2 phosphorylation. Nature Cell Biol. 2001;3:973–982. doi: 10.1038/ncb1101-973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uchida C, et al. Enhanced Mdm2 activity inhibits pRB function via ubiquitin-dependent degradation. EMBO J. 2005;24:160–169. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang JY, et al. MDM2 promotes cell motility and invasiveness by regulating E-cadherin degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:7269–7282. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00172-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ries S, et al. Opposing effects of Ras on p53: transcriptional activation of mdm2 and induction of p19ARF. Cell. 2000;103:321–330. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00123-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phelps M, Phillips A, Darley M, Blaydes JP. MEk–ERk signaling controls Hdm2 oncoprotein expression by regulating hdm2 mRNA export to the cytoplasm. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16651–16658. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412334200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaw RJ, Cantley LC. Ras, PI(3)k and mTOR signalling controls tumour cell growth. Nature. 2006;441:424–430. doi: 10.1038/nature04869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ding Q, et al. Erk associates with and primes GSk-3β for its inactivation resulting in upregulation of β-catenin. Mol Cell. 2005;19:159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brunet A, et al. Akt promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a Forkhead transcription factor. Cell. 1999;96:857–868. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Honda R, Yasuda H. Activity of MDM2, a ubiquitin ligase, toward p53 or itself is dependent on the RING finger domain of the ligase. Oncogene. 2000;19:1473–1476. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Honda R, Yasuda H. Association of p19(ARF) with Mdm2 inhibits ubiquitin ligase activity of Mdm2 for tumor suppressor p53. EMBO J. 1999;18:22–7. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Honda R, Tanaka H, Yasuda H. Oncoprotein MDM2 is a ubiquitin ligase E3 for tumor suppressor p53. FEBS Lett. 1997;420:25–27. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Medema RH, Kops GJ, Bos JL, Burgering BM. AFX-like Forkhead transcription factors mediate cell-cycle regulation by Ras and PkB through p27kip1. Nature. 2000;404:782–787. doi: 10.1038/35008115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin SY, et al. β-catenin, a novel prognostic marker for breast cancer: its roles in cyclin D1 expression and cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4262–4266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060025397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tetsu O, McCormick F. β-catenin regulates expression of cyclin D1 in colon carcinoma cells. Nature. 1999;398:422–426. doi: 10.1038/18884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Storz P, Doppler H, Toker A. Protein kinase D mediates mitochondrion-to-nucleus signaling and detoxification from mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:8520–8530. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.19.8520-8530.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Terry DE, Umstot E, Desiderio DM. Optimized sample-processing time and peptide recovery for the mass spectrometric analysis of protein digests. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2004;15:784–794. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee DF, et al. Ikkβ suppression of TSC1 links inflammation and tumor angiogenesis via the mTOR pathway. Cell. 2007;130:440–455. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hirosawa M, Hoshida M, Ishikawa M, Toya T. MASCOT: multiple alignment system for protein sequences based on three-way dynamic programming. Comput Appl Biosci. 1993;9:161–167. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/9.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang JY, et al. The tumor suppression activity of E1A in HER-2/neu-overexpressing breast cancer. Oncogene. 1997;14:561–568. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Note: Supplementary Information is available on the Nature Cell Biology website.