Abstract

Objective

Nanofiber scaffolds with amino groups conjugated to fiber surface through different spacers (ethylene, butylenes, and hexylene groups, respectively) were prepared and the effect of spacer length on adhesion and expansion of umbilical cord blood hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) was investigated.

Materials and Methods

Electrospun polymer nanofiber scaffolds were functionalized with poly(acrylic acid) grafting, followed by conjugation of amino groups with different spacers. HSPCs were expanded on aminated scaffolds for 10 days. Cell proliferation, surface marker expression, clonogenic potential, and nonobese diabetic (NOD)/severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) repopulation potential of the expanded cells were evaluated following expansion culture.

Results

Aminated nanofiber scaffolds with ethylene and butylene spacers showed high-expansion efficiencies (773- and 805-fold expansion of total cells, 200- and 235-fold expansion of CD34+CD45+ cells, respectively). HSPC proliferation on aminated scaffold with hexylene spacer was significantly lower (210-fold expansion of total cells and 86-fold expansion of CD34+CD45+ cells), but maintained the highest CD34+CD45+ cell fraction (41.1%). Colony-forming unit granulocyte-erythrocyte-monocyte-megakaryocyte and long-term culture-initiating cell maintenance was similar for HSPCs expanded on all three aminated nanofiber scaffolds; nevertheless, the NOD/SCID mice engraftment potential of HSPCs expanded on aminoethyl and aminobutyl conjugated nanofibers was significantly higher than that on aminohexyl conjugated nanofibers.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that aminated nanofibers are superior substrates for ex vivo HSPC expansion, which was correlated with the enhanced HSPC adhesion to these aminated nanofibers. The spacer, through which amino groups were conjugated to nanofiber surface, affected the expansion outcome. Our results highlighted the importance of scaffold topography and cell-substrate interaction to regulating HSPC proliferation and self-renewal in cytokine-supplemented expansion.

Human umbilical cord blood (UCB) hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) are multipotent cells that have the capacity to self-renew and differentiate into all mature blood cell types [1,2]. However, the low number of HSPCs obtainable from umbilical cords due to the small volume of blood collected limits direct UCB HSPC transplantation treatments to pediatric patients. Therefore, several approaches have been explored to expand HSPCs in ex vivo expansion systems, so that UCB could serve as a readily viable source of transplantable HSPCs for adult patients suffering from a variety of hematological disorders [3–7].

In conventional ex vivo expansion culture, HSPCs are generally regarded as suspension cells and numerous protocols implement HSPC suspension cultures in flasks or bags in the presence of various combinations of early acting cytokines [3–7]. The importance of topographical and substrate-immobilized biochemical cues has not been taken into consideration in these culture systems. Suspension culture conditions differ drastically from conditions provided by the natural bone marrow microenvironment, where a complex network of stromal cells and extracellular matrix (ECM) serves as a stem cell niche that regulates HSPC functions such as homing, self-renewal, proliferation, and fate choice [2,8]. A growing body of evidence has suggested the importance of substrate surface chemistry and topography on the rate of HSPC proliferation and CD34+ cell expansion [9–12].

Recently, we have demonstrated that surface covalent immobilization of ECM proteins (fibronectin) [10] and adhesion peptides (CS-1 and RGD) [11] can mediate HSPC adhesion to the substrate and HSPC expansion. We have also shown that surface-aminated nanofiber scaffold could mediate HSPC proliferation [12]. In particular, we discovered that surface amino groups and nanofiber topographical cue played synergistic roles in enhancing cell-substrate adhesion and maintenance of HSPC proliferation and phenotype. HSPCs proliferation was the highest on aminated nanofiber scaffold and showed significant adhesion and maintenance of primitive colony-forming unit granulocyte-erythrocyte-monocyte-megakaryocyte (CFU-GEMM)–forming cells.

Here we further examine the effect of amino group conjugation to nanofiber surface on HSPC expansion, with the goal to better understand the extent by which aminated nanofiber mediates HSPC adhesion and proliferation. Several studies had shown that spacer properties can significantly influence the interaction between cells and immobilized biofunctional molecules, such as cell adhesion ligands [13–15], providing motivation to investigate the effect of chain length of the grafted amines on the proliferation rate, phenotype maintenance, clonogenic potential, as well as engraftment potential of cultured cord blood HSPCs.

Materials and methods

Fabrication of polyethersulfone nanofiber scaffolds

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise stated. Polyethersulfone (PES) granules (molecular weight: 55,000 g/mol) was purchased from Goodfellow Cambridge Limited (Cambridge, UK). PES pellets were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) at 20 wt% concentration and placed in a plastic syringe fitted with a 27-gauge needle. A syringe pump (KD Scientific, Holliston, MA, USA) was used to feed the polymer solution into the needle tip. The feed rate of the syringe pump was fixed at 0.3 mL/h. The PES nanofiber meshes were fabricated by electrospinning at 13 kV using a high-voltage power supply (Gamma High Voltage Research, Ormand Beach, FL, USA). Nanofibers were collected directly onto grounded 15-mm diameter glass coverslips (Paul Marienfeld GmbH & Co. KG, Lauda-Königshofen, Germany) located at a fixed distance of 16 cm from the needle tip, over a collection time of 25 minutes. The deposited nanofiber samples were then washed thoroughly in distilled water and then in ethanol to remove any residual DMSO, and subsequently dried and stored in a desiccator.

Surface grafting of scaffolds with poly(acrylic acid)

Acrylic acid was distilled and stored at −20°C prior to use. Poly (acrylic acid) (PAAc) was grafted onto the PES nanofiber mesh surface by photo polymerization. Samples were immersed in aqueous solution containing 3% acrylic acid solution and 0.5 mM NaIO4 in a flat-bottom glass container. The temperature of the solution was maintained at 8°C by cooling the container in a cold-water bath. Samples were then exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light from a 400-W mercury lamp (5000-EC; Dymax, Germany) for 2 minutes at a distance of 25 cm. The PAAc-grafted meshes were then thoroughly washed with deionized water at 37°C for more than 36 hours to remove any ungrafted PAAc from the surface of the scaffold and dried in a storage desiccator.

Amination of PAAc-grafted scaffolds

The PAAc-grafted PES nanofiber meshes were further reacted with 1,2-ethanediamine (EtDA), 1,4-butanediamine (BuDA) or 1,6-hexanediamine (HeDA) using carbodiimide cross-linking method. Briefly, each scaffold was first gently shaken in 2 mL acetonitrile containing 50 mM N-hydroxysuccinimide and 50 mM di-cyclohexylcarbodiimide. After 6 hours, the reaction solution was carefully aspirated and each scaffold was immediately immersed into 2 mL acetonitrile containing 0.03 mmol EtDA, BuDA, or HeDA. After 12 hours, the reaction solution was carefully aspirated and each scaffold was thoroughly washed in absolute ethanol to remove any dicyclohexyl urea, a byproduct of the conjugation reaction. All substrates were subsequently sterilized in 70% ethanol, then loaded into 24-well tissue culture plates (Nunc, Denmark) and stored in sterile phosphate-buffered saline until use. Surface characterization and atomic compositions of various PES nanofiber surfaces were determined using x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, PHI-1800; Physical Electronics, Chanhassen, MN, USA). Binding energies were referenced to the CC/CH2 C(1s) peak at 284.6 eV.

Ex vivo HSPC expansion culture

Frozen human umbilical cord blood CD34+ HSPCs were purchased from AllCells, LLC (Emeryville, CA, USA). The CD34+ purity in the post-thawed HSPC was determined to be 98% by flow cytometry and the viability was determined to be more than 97% by Trypan blue. Purified recombinant human stem cell factor (SCF), Flt-3 ligand (Flt3), thrombopoietin (TPO), and IL-3 was purchased from Peprotech Inc. (Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) was purchased from Athens Research & Technology Inc. (Athens, GA, USA).

Six-hundred HSPCs were seeded onto each scaffold. HSPCs were cultured in 0.6 mL StemSpan serum-free expansion medium (StemCell Technologies Inc., Vancouver, BC, Canada) supplemented with 0.04 mg/mL LDL, 100 ng/mL SCF, 100 ng/mL Flt3, 50 ng/mL TPO, and 20 ng/mL IL-3 at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 10 days. Similar cultures were also performed on tissue culture polystyrene surface (TCPS), which serve as a positive control in this study. In total, six surface conditions were tested: TCPS, unmodified PES nanofiber mesh (Unmod), carboxylated nanofiber mesh (PAAc), and nanofiber mesh aminated with EtDA, BuDA, or HeDA. After 10 days of culture, the expanded cells were harvested and aliquoted according to protocols described previously [11,12]. Aliquots of the concentrated cells were then used for cell counting by a hematocytometer, flow cytometry analysis, colony-forming cell (CFC) assay, long-term culture-initiating cell (LTC-IC) assay and mouse engraftment assay.

Flow cytometry

Cell samples were stained with fluorescently labeled CD13, CD34, and CD45 antibodies (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) according to protocols described previously [12]. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur, BD Biosciences). Relevant isotype controls were also included to confirm specificity and for compensation setting. The Milan-Mulhouse gating method was used for cell enumeration [16].

Preparation of culture samples for scanning electron microscopy

Selected culture samples were gently rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline, fixed with 3% glutaraldehyde, and postfixed with 1% osmium tetraoxide. Samples were then dehydrated using a graded series of ethanol followed by hexamethyldisilazane drying. Samples were gold sputter-coated before viewing under field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM; FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR, USA).

CFC and LTC-IC assays

For CFC, aliquots of expanded cells from each scaffold condition in the expansion cultures were cultured in two dishes per sample in MethoCult GF+ H4435 medium (StemCell Technologies Inc.). The dishes were then incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 14 days, after which the number of erythropoietic colonies (burst-forming unit erythroid), granulopoietic colonies (colony-forming unit granulocyte macrophage [CFU-GM]), and multilineage colonies (CFU-GEMM) were enumerated with the aid of an inverted microscope and counted by morphologic criteria. For control, freshly thawed HSPCs were also evaluated for colony-forming potential.

For LTC-IC, expanded cells from each scaffold condition in the ex vivo hematopoietic expansion cultures and freshly thawed HSPCs, which serve as controls, were plated onto irradiated M2-10B4 murine fibroblast feeder cells in 35-mm culture dishes and cultured in MyeloCult H5100 medium (StemCell Technologies Inc.). After 5 weeks, cells from each dish were harvested, and cultured according to the CFC assay as described above. LTC-IC numbers were then calculated and normalized according to instructions in the StemCell Technologies procedure manual.

Mouse engraftment assay

NOD/SCID mice were maintained and handled at the Biological Resource Center (BRC, Biopolis, Singapore), according to BRC regulations. Six-to-eight-week-old mice were irradiated at 350 cGy. Cells harvested from the 10-day ex vivo expansion culture were mixed with 4 × 105 irradiated (1500 cGy) CD34-depleted human bone marrow cells (carrier cells) and injected into mice via the tail vein. As positive controls, two groups of mice received 600 and 20,000 unexpanded HSPCs together with 4 × 105 irradiated carrier cells, respectively. A group of irradiated mice were injected with 4 × 105 irradiated carrier cells only serve as the negative control. Mice were sacrificed 6 weeks after cell transplantation. Bone marrow cells are harvested and stained with fluorescently labeled human CD45 antibody according to protocols described previously [10,11], and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

All data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The statistical significance of the data obtained was analyzed by non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test for mouse engraftment results and Student’s t-test for all other results. Probability values of p < 0.05 were interpreted as denoting statistical significance.

Results

Surface characterization of aminated nanofiber scaffolds

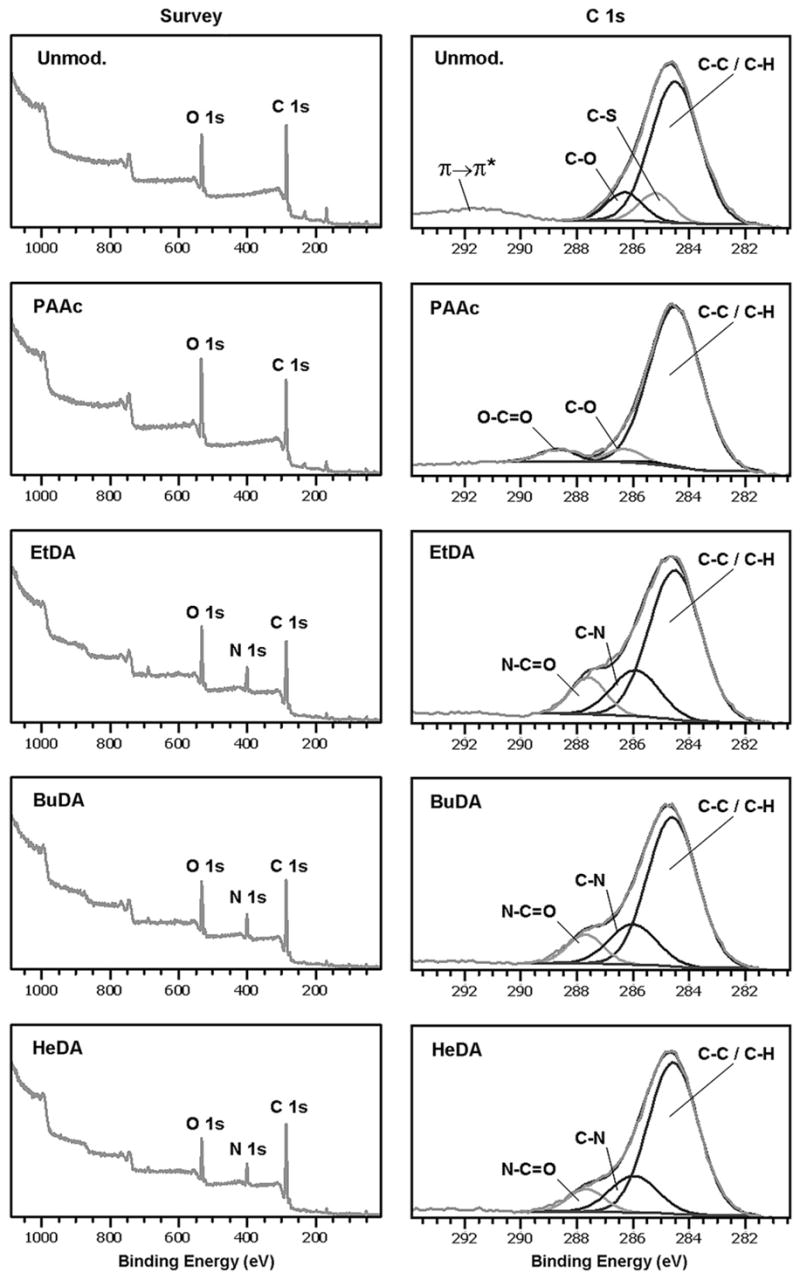

Nonwoven PES nanofiber meshes with an average diameter of 529 ± 114 nm were prepared by electrospinning process. The PES nanofiber meshes were first carboxylated by UV-initiated PAAc grafting and subsequently reacted with diamines with two, four, or six carbon spacers (EtDA, BuDA, or HeDA, respectively) using carbodiimide cross-linking chemistry. XPS analysis showed that surface nitrogen abundance on the aminated fibers was between 11.6% and 13.4% (Fig. 1 and Table 1), which indicated similar conjugation efficiencies of amino groups on different nanofiber surfaces. The unmodified and PAAc-grafted fibers, on the other hand, showed a background surface nitrogen abundance of <0.2%.

Figure 1.

The XPS spectra of various polyethersulfone nanofiber scaffolds. BuDA = 1,4-butanediamine; EtDA = 1,2-ethanediamine; HeDA = 1,6-hexanediamine; PAAc = poly(acrylic acid).

Table 1.

XPS elemental analysis of polyethersulfone nanofiber surfaces modified with different functional groups

| PES nanofiber scaffolds | C atomic abundance (%) | O atomic abundance (%) | N atomic abundance (%) | S atomic abundance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unmodified | 74.2 | 20.2 | 0.2 | 5.4 |

| PAAc-grafted | 68.6 | 27.7 | 0.1 | 3.6 |

| EtDA-conjugated | 65.2 | 19.8 | 13.4 | 1.6 |

| BuDA-conjugated | 67.9 | 17.5 | 13.2 | 1.4 |

| HeDA-conjugated | 71.8 | 14.9 | 11.6 | 1.7 |

BuDA = 1,4-butanediamine; EtDA = 1,2-ethanediamine; HeDA = 1,6-hexanediamine; PAAc = poly(acrylic acid); PES = polyethersulfone.

In addition, the carbon XPS spectra (C1s) showed that following PAAc grafting, the weak π → π* shake-up satellite peak at 291.7 eV (attributed to aromatic carbon species in PES) was absent, and replaced by the characteristic O–C=O peak from grafted PAAc chains (Fig. 1). Subsequently, C1s spectra of amine-conjugated nanofiber meshes showed the absence of O–C=O peak, indicating the complete conversion of surface PAAc carboxylic acid groups to amide groups during the amination reaction.

Ex vivo HSPC expansion on aminated nanofiber scaffolds

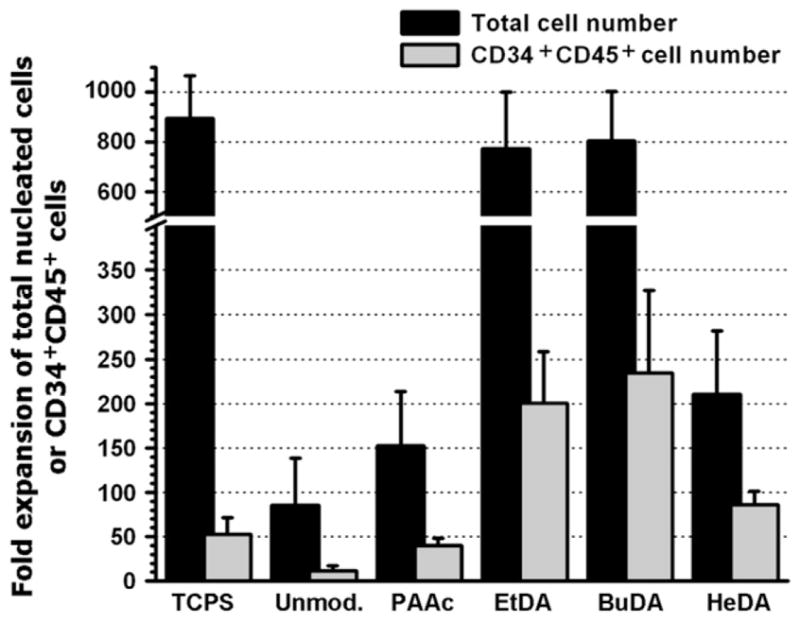

The efficiency of nanofiber scaffolds on supporting HSPC expansion was evaluated through a 10-day expansion culture. Figure 2 showed the fold expansions of total nucleated cells and CD34+CD45+ cells cultured on aminated nanofiber scaffolds with different spacers and control surfaces. Cells harvested from the expansion culture showed over 95% viability in all culture conditions. HSPCs cultured on unmodified and PAAc-grafted nanofibers yielded the lowest proliferation of total nucleated cells (85- and 152-fold, respectively) with 13.3% and 26.1% CD34+CD45+ cells among expanded cells, respectively, corresponding to low expansion efficiencies of CD34+CD45+ cells (11-and 40-fold, respectively). Although HSPCs cultured on TCPS surface proliferated extensively (895-fold), only 5.9% of the expanded cells were CD34+CD45+ cells, corresponding to a 53-fold expansion of CD34+CD45+ cells.

Figure 2.

Fold expansion of total nucleated cells and CD34+ CD45+ cells following a 10-day culture of human cord blood hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells on tissue culture polystyrene surface and various polyethersulfone nanofiber scaffolds. Bars represent means ± SD of three to eight independent experiments, each conducted in triplicates. BuDA = 1,4-butanediamine; EtDA = 1,2-ethanediamine; HeDA = 1,6-hexanediamine; PAAc = poly(acrylic acid).

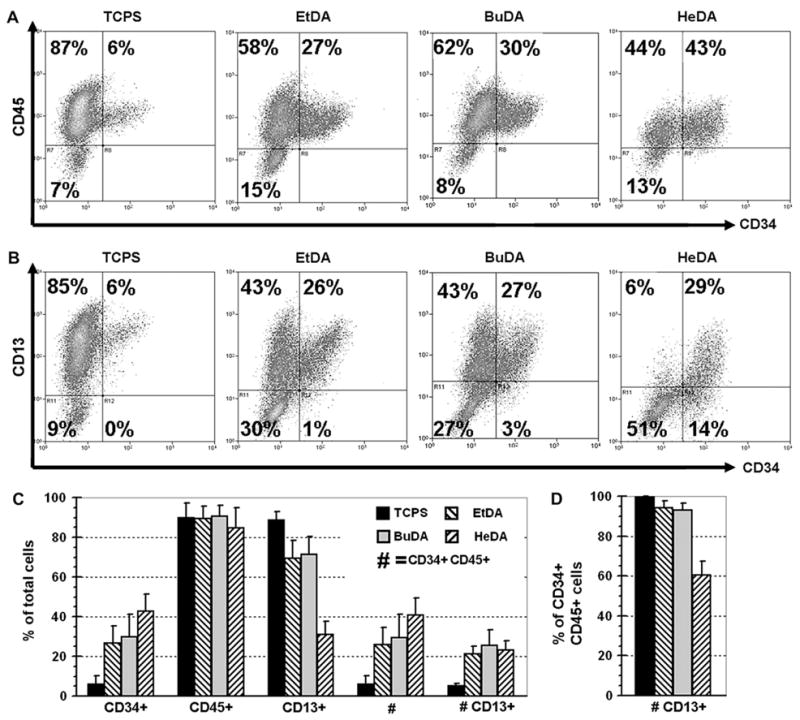

In comparison, expansion efficiencies of CD34+CD45+ cells on all aminated nanofiber meshes were higher than aforementioned test groups: EtDA and BuDA nanofiber meshes resulted in similar expansion profiles (p > 0.05) and yielded 773- and 805-fold expansion of total cells (Fig. 2) with 25.9% (200-fold expansion) and 29.2% (235-fold expansion) of CD34+CD45+ cells, respectively (Fig. 3). Overall proliferation of HSPCs on HeDA nanofibers was significantly lower as compared with EtDA and BuDA fiber meshes (210-fold, p < 0.05), however, the fraction of CD34+CD45+ cells was the highest at 41.1% of total cells (86-fold CD34+CD45+ cell expansion). An interesting observation was that the CD34+CD45+ cell population expanded on HeDA nanofiber scaffold coexpressed significantly lower level of the myeloid CD13 marker (60.3% ± 7.3% of expanded CD34+CD45+ cell population) compared to EtDA and BuDA nanofiber scaffolds (94.2% ± 3.5% and 92.8% ± 3.8%, respectively, p < 0.05, Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Representative fluorescein-activated cell sorting profiles (A,B) and surface marker expression summary (C,D) of expanded cells after 10-day hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell expansion cultures on culture polystyrene surface, and 1,2-ethanediamine (EtDA), 1,4-butanediamine (BuDA), and 1,6-hexanediamine (HeDA) nanofiber scaffolds. (A) CD45 vs CD34. (B) CD13 vs CD34. (C) Percentage of total cells expressing one or multiple CD markers. (D) Percentage of the CD34+CD45+ cell population that are CD13+. Bars represent means ± SD of five to eight experiments, each conducted in duplicates.

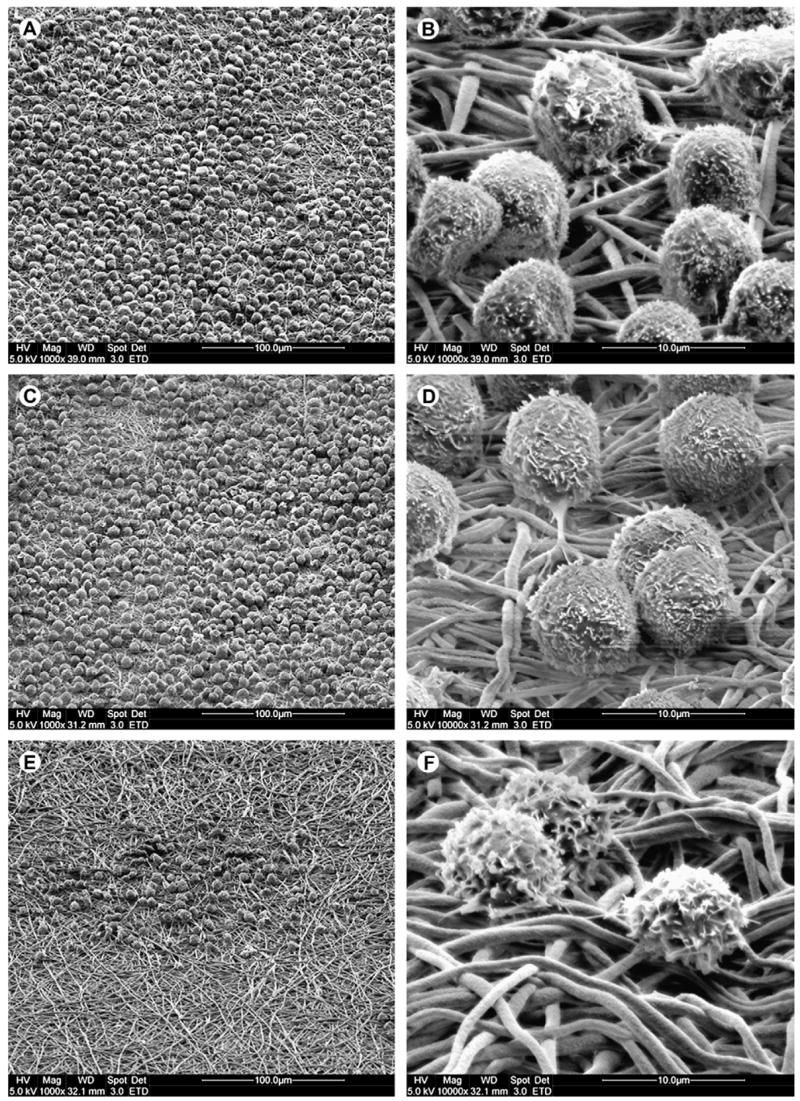

Morphology of adherent cells on aminated scaffolds

SEM imaging was used to monitor the proliferation kinetics of the adherent HSPC population on aminated nanofiber scaffolds. At selected time points during the 10-day expansion culture, samples were processed for SEM to image the adherent cells and their interaction with nanofibers. We have noted previously that expanded cells adhered weakly to TCPS, unmodified, and PAAc-grafted surfaces. Most of expanded cells were washed off easily with very gentle rinsing [11,12]; only sparsely scattered cells remained adherent, as visualized by SEM imaging.

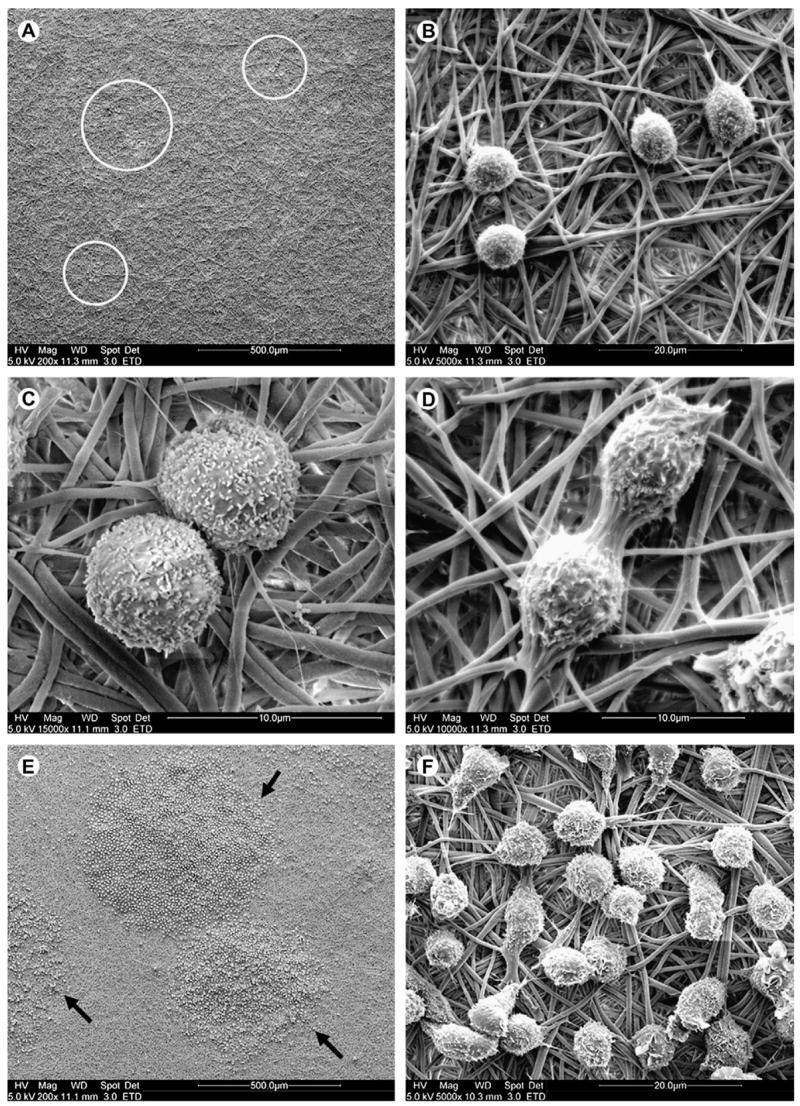

Both EtDA and BuDA modified nanofiber meshes mediated significant adhesion. On day 3, small pockets of adherent HSPCs could be observed interacting with and proliferating on these fiber meshes (Fig. 4A and B). The adherent HSPCs were anchored to the aminated nanofibers via numerous uropodia radiating from the cell surface (Fig. 4C). Cells undergoing division were also evident on the nanofiber surface (Fig. 4D). By day 8, the adherent HSPCs proliferated to form distinct, densely populated circular cell colonies on aminated nanofiber meshes (Fig. 4E and F). The distinct circular cell colonies most likely arose from single or small clusters of HSPCs proliferating outwards in a radial manner on nanofiber scaffold. Cell colonies ranged from 0.1 to 1.3 mm in diameter, with cells numbering between 50 and a few thousand.

Figure 4.

Scanning electron microscope images of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) after (A–D) 3-day and (E,F) 8-day cultures on polyethersulfone 1,4-butanediamine nanofiber mesh at various magnifications. (A,B) Pockets of adherent HSPCs were observed (white circles) proliferating on the aminated nanofiber surface on day 3. (C) Cells exhibited numerous filopodia, which were interacting with the aminated nanofibers. (D) Cell division was observed occurring on the nanofiber surface. (E,F) HSPCs proliferated to form circular colonies (black arrows) on the nanofiber surface, shown on day 8.

Adherent HSPCs proliferated well on both EtDA (Fig. 5A and B) and BuDA (Fig. 5C and D) nanofiber surfaces to form densely populated cell colonies after 10 days of culture, and this was mirrored by the high mononucleated cell counts (Fig. 2). In contrast, the considerably lower proliferation rate on HeDA-modified nanofiber surface (210-fold; Fig. 2) was reflected by smaller colony size, each containing <50 cells (Fig. 5E and F). Besides differences in adherent cell density and colony size, no obvious morphological differences could be discerned among the adherent cells expanded on the EtDA, BuDA, or HeDA nanofiber meshes.

Figure 5.

Scanning electron microscope images of adherent cell colonies after 10 days of expansion on aminated polyethersulfone nanofibers conjugated with 1,2-ethanediamine (EtDA) (A,B), 1,4-butanediamine (BuDA) (C,D) and 1,6-hexanediamine (HeDA) (E,F), respectively. Colonies of densely packed adherent cells were observed on EtDA and BuDA nanofiber surfaces. On HeDA nanofiber surfaces, adherent cells were sparsely located.

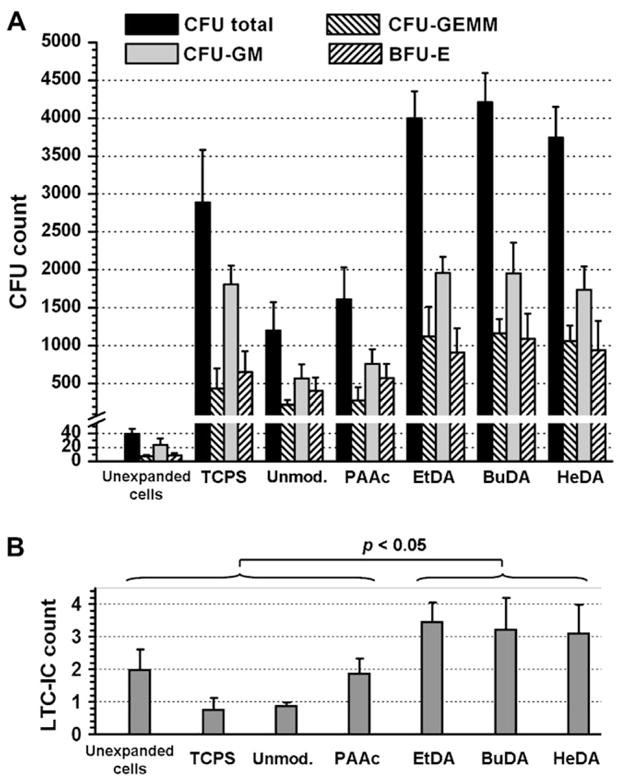

HSPC clonogenic potential from various scaffolds

CFC and LTC-IC assays were conducted to evaluate the fraction of primitive progenitor cells in the expanded cultures. The CFC results (Fig. 6A) showed that cells expanded from unmodified and PAAc-grafted nanofiber meshes yielded lower total CFU counts (1199 and 1609, respectively) as compared to TCPS control (2890, p < 0.05). Conversely, cells expanded from EtDA, BuDA, and HeDA nanofiber meshes yielded significantly higher total CFU counts (3996, 4208 and 3742, respectively) compared to TCPS control (p < 0.05). In addition, significant differences were also observed in the number of primitive CFU-GEMM units generated by cells expanded on EtDA, BuDA, and HeDA nanofiber meshes; 28.1%, 27.6%, and 28.4% of total colony counts, respectively were CFU-GEMM units, compared with that expanded on TCPS (15.0%, p < 0.05). TCPS, on the other hand, generated higher percentages of CFU-GM units (63%), indicating stronger differentiation commitment towards the myeloblast/monoblast lineage.

Figure 6.

(A) Colony-forming unit (CFU) counts after 14 days of culture; and (B) long-term culture-initiating cell (LTC-IC) counts after 7 weeks of culture, from unexpanded hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) and from expanded cells after 10-day HSPC expansion cultures on tissue culture polystyrene surface (TCPS) and various polyethersulfone nanofiber scaffolds, normalized to CFU or LTC-IC per 100 initial unexpanded HSPCs. (A) Bars represent means ± SD of three to eight experiments, each conducted in triplicate. (B) Bars represent means ± SD of two experiments, each conducted in triplicate. BFU-E = burst-forming unit erythroid; BuDA = 1,4-butanediamine; CFU-GEMM = CFU granulocyte-erythrocyte-monocyte-megakaryocyte; CFU-GM = CFU granulocyte macrophage; EtDA = 1,2-ethanediamine; HeDA = 1,6-hexanediamine; PAAc = poly(acrylic acid).

Results from LTC-IC assays (Fig. 6B) suggested that HSPCs expanded from EtDA-, BuDA-, and HeDA-scaffolds better preserved the primitive potential than those cultured on control surfaces. LTC-IC counts generated from HSPCs expanded on these fiber scaffolds were significantly higher than that from unexpanded cells (p < 0.05), suggesting significant degree of HSPC self-renewal on aminated nanofiber scaffolds. Interestingly, cells expanded from HeDA nanofiber scaffolds generated comparatively high numbers of colony units similar to EtDA and BuDA conditions (Fig. 6), even though the total cell expansion (Fig. 2) was shown to be low. This may be attributed to the relatively high CD34+ phenotype expression of cells expanded on HeDA nanofiber scaffold.

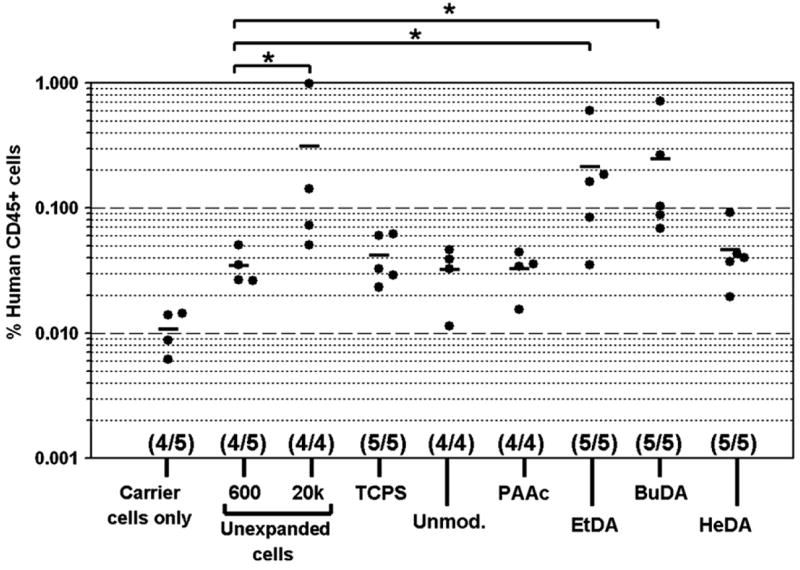

NOD/SCID repopulation potential of cells expanded on various scaffolds

To access the effect of surface-modified nanofiber scaffolds on the maintenance of the engraftment potential of HSPCs, cells harvested from 10-day expansion cultures were injected intravenously into sublethally irradiated NOD/SCID mice together with 4 × 105 irradiated carrier cells. As positive controls, 600 and 20,000 (“20k” group in Fig. 7) unexpanded CD34+ cells were also injected into two groups of mice. The presence of >0.1 % of human CD45+ cells among murine bone marrow cells after 6 weeks was used as a criterion for successful primary engraftment in the bone marrow of NOD/SCID mice. Based on this criterion, the groups that yielded positive primary engraftment included cells expanded on EtDA and BuDA scaffolds and 20,000 freshly thawed unexpanded cells (Fig. 7). Moreover, there was statistical significance between EtDA vs 600 cells and BuDA vs 600 cells groups (p < 0.05), indicating improvement of HSPC engraftment potential following ex vivo expansion on EtDA and BuDA nanofiber scaffolds (600 cells were seeded initially for expansion cultures). Nevertheless, HeDA fiber group failed to show positive engraftment, even though its corresponding CFC and LTC-IC results were comparable to those of EtDA and BuDA groups, suggesting a disjunction between clonogenic and engraftment potential.

Figure 7.

Engraftment efficiency of human CD45+ cells in bone marrow of sublethally irradiated nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient transplanted with unexpanded hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs), expanded cells derived from 600 CD34+ cells following 10-day expansion culture on tissue culture polystyrene surface (TCPS) and various polyethersulfone nanofiber scaffolds, and irradiated carrier cells alone. Numbers in parentheses indicate mice survival in the different experimental groups. *p < 0.05. BuDA = 1,4-butanediamine; EtDA = 1,2-ethanediamine; HeDA = 1,6-hexanediamine; PAAc = poly(acrylic acid).

Discussion

This study investigates the effect of covalently grafted amino groups, in conjunction with spacer chain length and surface nanofiber topography, on ex vivo expansion and multipotency maintenance of human umbilical cord HSPCs in cytokine-supplemented serum-free culture. Our results confirmed that HSPCs expanded on aminated nanofiber scaffolds generated significantly higher numbers of total CFU, CFU-GEMM units, and LTC-IC counts, in contrast to those cultured on unmodified and carboxylated nanofiber scaffolds and TCPS substrate.

The SEM images provided direct evidence of HSPC adhesion on aminated nanofiber scaffolds. Despite varying degrees of proliferation, intimate binding of cells with nanofibers was evident for all three types of aminated nanofibers, forming strikingly distinct circular colonies. Numerous threadlike processes and uropodia emanating from the cell surface [17] apparently anchored the cells to nanofibers and likely mediated the migration of these cells as well. Little cell-to-cell contact was observed. This unique adhesion pattern suggests that the submicron scale feature presented by electrospun fibers promotes contact guidance for dividing cells as they adhere and migrate away from the center of the colony. This observation is in contrast to HSPCs expanded on aminated two-dimensional film, which did not display significant adhesion and “colony formation” [11,12].

Our data suggests that substrates that promoted cell adhesion also enhanced the preservation of CD34+CD45+ phenotype and the primitive characteristics of cord blood CD34+ HSPCs. Cell adhesion/retention is known to be a crucial function of the stem cell niche in vivo. Current understanding of HSC biology implicates the roles of cell adhesion molecules N-cadherin and fibronectin in regulating stem cell quiescence and self-renewal [18]. The positive effects of surface-immobilized fibronectin in promoting expansion and maintenance of primitive characteristics of HSPCs have been demonstrated in several studies [10,11,19–23]. In this study, nanofibers were not specifically modified with cell-adhesion ligands; and cells were cultured in serum-free medium. A preliminary analysis revealed that VLA-4 and VLA-5 expression were not altered for both the adherent fraction and suspension fraction of the expanded cells on aminated nanofibers (data not shown), suggesting that integrins might not be involved cell-fiber adhesion. On the other hand, we found significantly higher expression of CD34 among adherent fraction than nonadherent fraction of cells (data to be published separately). This indicates that HSPC adhesion to these aminated fibers is probably through an integrin-independent mechanism that promotes the preservation of primitive characteristics of HSPCs.

Given the positively charged nature of the fiber surface and that CD34 antigen is a highly sialylated and negatively charged glycophosphoprotein, we hypothesize that the initial adhesion of HSPCs on aminated nanofibers is likely mediated by CD34 antigen via electrostatic charge-to-charge interaction. Recent reports also provided some supporting evidence for our hypothesis [24–27]. Under normal condition, due to its halo of negatively charged sialic acid, CD34 antigen functions as anti-adhesin, preventing cell-to-cell adhesion between HSPCs. However, when CD34 is bound to antibodies or to its putative extracellular ligand that is yet to be identified [25], cell-to-cell adhesion is enhanced, either through concentration of CD34 to a cap region [26], and/or through antibody-CD34 (or ligand-CD34) mediated intracellular signaling [24–27], which may result in an upregulation of cell-adhesive molecules in HSPCs [25]. Therefore, it is likely that HSPCs interact with surface amino groups, either directly mediate or indirectly facilitate HSPC adhesion to the substrate.

Another interesting finding of this study is that amine groups tethered through two- or four-carbon spacers exerted more beneficial effects than that through a six-carbon spacer on total cell expansion, CD34+CD45+ cell proliferation, and preservation of SCID-repopulating cell (SRC) capacity. Extending the spacer from two- or four-carbons to six-carbon reduced total cell expansion by 3.8 times but increased CD34+CD45+ cell fraction by 1.5 times. It appears that HeDA nanofiber scaffold was most efficient at preserving the CD34+ phenotype at the expense of overall cell proliferation. The expanded cells on HeDA nanofibers showed similar total CFU and CFU-GEMM counts and LTC-IC counts, but lower SRC activity compared to aminated fibers with shorter spacers.

The lower SRC activity of the cells expanded on aminated fibers with six-carbon spacer might be a consequence of the lower numbers of total transplanted cells and CD34+CD45+ cells (Fig. 2). This result supports the notion that the total cell dose, in addition to the fraction of stem/progenitor cells content, is also a critical parameter for successful engraftment during transplantation [3–5,28,29]. On the other hand, this lower SRC activity of infused cells harvested from aminated fibers with six-carbon spacer was also likely a result of lower number of infused CD34+CD45+CD13+ cells (Fig. 3D). This explanation can be supported by a recent report suggesting a highly positive correlation between myeloid marker expression and the engraftment potential of human CD34+ HSPCs [30]. These results warrant more studies to investigate molecular and cellular mechanisms. It is possible that two- and four-carbon spacers provided a sterically favorable conformation for interaction between amine groups and CD34 antigen. It is also possible that the interaction requires that the amine group be anchored with a certain degree of rigidity.

In summary, we have demonstrated that aminated nanofibers enhanced cell-substrate adhesion and ex vivo expansion of HSPCs; and the spacer, through which amino groups were conjugated to nanofiber surface, significantly influenced HSPC adhesion and expansion outcome. Our results highlighted the importance of scaffold topography and cell-substrate interaction to regulating HSPC proliferation and self-renewal in cytokine-supplemented expansion.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yen-Ni Tang and Chai-Hoon Quek of Johns Hopkins in Singapore for the technical assistance and helpful discussion. The authors acknowledge the surface analysis laboratory at the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University for the use of XPS. This work was partially supported by the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A* STAR) of Singapore, Whitaker Biomedical Engineering Institute at Johns Hopkins University, and NIH to K.W.L. (EB003447 and HL-083008).

References

- 1.Dzierzak E. Hematopoietic stem cells and their precursors: developmental diversity and lineage relationships. Immunol Rev. 2002;187:126–138. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2002.18711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonnet D. Biology of human bone marrow stem cells. Clin Exp Med. 2003;3:140–149. doi: 10.1007/s10238-003-0017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eridani S, Mazza U, Massaro P, La Targia ML, Maiolo AT, Mosca A. Cytokine effect on ex vivo expansion of haemopoietic stem cells from different human sources. Biotherapy. 1998;11:291–296. doi: 10.1023/a:1008081708054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagner JE, Verfaillie CM. Ex vivo expansion of umbilical cord blood hemopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Exp Hematol. 2004;32:412–413. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sorrentino BP. Clinical strategies for expansion of haematopoietic stem cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:878–888. doi: 10.1038/nri1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams SF, Lee WJ, Bender JG, et al. Selection and expansion of peripheral blood CD34(+) cells in autologous stem cell transplantation for breast cancer. Blood. 1996;87:1687–1691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reiffers J, Cailliot C, Dazey B, Attal M, Caraux J, Boiron JM. Abrogation of post-myeloablative chemotherapy neutropenia by ex-vivo expanded autologous CD34-positive cells. Lancet. 1999;354:1092–1093. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03113-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takagi M. Cell processing engineering for ex-vivo expansion of hematopoietic cells. J Biosci Bioeng. 2005;99:189–196. doi: 10.1263/jbb.99.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LaIuppa JA, McAdams TA, Papoutsakis ET, Miller WM. Culture materials affect ex vivo expansion of hematopoietic progenitor cells. J Biomed Mater Res. 1997;36:347–359. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19970905)36:3<347::aid-jbm10>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feng Q, Chai C, Jiang XS, Leong KW, Mao HQ. Expansion of engrafting human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in three-dimensional scaffolds with surface-immobilized fibronectin. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;78:781–791. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang XS, Chai C, Zhang Y, Zhuo RX, Mao HQ, Leong KW. Surface-immobilization of adhesion peptides on substrate for ex vivo expansion of cryopreserved umbilical cord blood CD34(+) cells. Biomaterials. 2006;27:2723–2732. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chua KN, Chai C, Lee PC, et al. Surface-aminated electrospun nanofibers enhance adhesion and expansion of human umbilical cord blood hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Biomaterials. 2006;27:6043–6051. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bakowsky U, Schumacher G, Gege C, Schmidt RR, Rothe U, Bendas G. Cooperation between lateral ligand mobility and accessibility for receptor recognition in selectin-induced cell rolling. Biochemistry. 2002;41:4704–4712. doi: 10.1021/bi0117596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chua KN, Lim WS, Zhang PC, et al. Stable immobilization of rat hepatocyte spheroids on galactosylated nanofiber scaffold. Biomaterials. 2005;26:2537–2547. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Houseman BT, Mrksich M. The microenvironment of immobilized Arg-Gly-Asp peptides is an important determinant of cell adhesion. Biomaterials. 2001;22:943–955. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gratama JW, Sutherland DR, Keeney M, Papa S. Flow cytometric enumeration and immunophenotyping of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2001;15:14–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Francis K, Palsson B, Donahue J, Fong S, Carrier E. Murine Sca-1(+)/Lin(−) cells and human KG1a cells exhibit multiple pseudopod morphologies during migration. Exp Hematol. 2002;30:460–463. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00778-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arai F, Hirao A, Suda T. Regulation of hematopoiesis and its interaction with stem cell niches. Int J Hematol. 2005;82:371–376. doi: 10.1532/IJH97.05100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sellers SE, Tisdale JF, Agricola BA, Donahue RE, Dunbar CE. The presence of the carboxy-terminal fragment of fibronectin allows maintenance of non-human primate long-term hematopoietic repopulating cells during extended ex vivo culture and transduction. Exp Hematol. 2004;32:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhatia R, Williams AD, Munthe HA. Contact with fibronectin enhances preservation of normal but not chronic myelogenous leukemia primitive hematopoietic progenitors. Exp Hematol. 2002;30:324–332. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(01)00799-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huygen S, Giet O, Artisien V, Di Stefano I, Beguin Y, Gothot A. Adhesion of synchronized human hematopoietic progenitor cells to fibronectin and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 fluctuates reversibly during cell cycle transit in ex vivo culture. Blood. 2002;100:2744–2752. doi: 10.1182/blood.V100.8.2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dao MA, Hashino K, Kato I, Nolta JA. Adhesion to fibronectin maintains regenerative capacity during ex vivo culture and transduction of human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Blood. 1998;92:4612–4621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schofield KP, Humphries MJ, de Wynter E, Testa N, Gallagher JT. The effect of alpha4 beta1-integrin binding sequences of fibronectin on growth of cells from human hematopoietic progenitors. Blood. 1998;91:3230–3238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Majdic O, Stockl J, Pickl WF, et al. Signaling and induction of enhanced cytoadhesiveness via the hematopoietic progenitor cell surface molecule CD34. Blood. 1994;83:1226–1234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Healy L, May G, Gale K, Grosveld F, Greaves M, Enver T. The stem cell antigen CD34 functions as a regulator of hemopoietic cell adhesion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:12240–12244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tada J, Omine M, Suda T, Yamaguchi N. A common signaling pathway via Syk and Lyn tyrosine kinases generated from capping of the sialomucins CD34 and CD43 in immature hematopoietic cells. Blood. 1999;93:3723–3735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan PC, Furness SG, Merkens H, et al. Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor-1 is a hematopoietic ligand for a subset of the CD34 family of stem cell surface proteins. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1150–1161. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Migliaccio AR, Adamson JW, Stevens CE, Dobrila NL, Carrier CM, Rubinstein P. Cell dose and speed of engraftment in placental/umbilical cord blood transplantation: graft progenitor cell content is a better predictor than nucleated cell quantity. Blood. 2000;96:2717–2722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stewart DA, Guo D, Luider J, et al. Factors predicting engraftment of autologous blood stem cells: CD34+ subsets inferior to the total CD34+ cell dose. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;23:1237–1243. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taussig DC, Pearce DJ, Simpson C, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells express multiple myeloid markers: implications for the origin and targeted therapy of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2005;106:4086–4092. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]