Abstract

Swallow and cough are complex motor patterns elicited by rapid and intense electrical stimulation of the internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve (ISLN). The laryngeal adductor response (LAR) includes only a laryngeal response, is elicited by single stimuli to the ISLN, and is thought to represent the brain stem pathway involved in laryngospasm. To identify which regions in the medulla are activated during elicitation of the LAR alone, single electrical stimuli were presented once every 2 s to the ISLN. Two groups of 5 cats each were studied; an experimental group with unilateral ISLN stimulation at 0.5 Hz and a surgical control group. Three additional cats were studied to evaluate whether other oral, pharyngeal or respiratory muscles were activated during ISLN stimulation eliciting LAR. We quantified up to 22 sections for each of 14 structures in the medulla to determine if regions had increased Fos-like immunoreactive neurons in the experimental group. Significant increases (p <0.0033) occurred with unilateral ISLN stimulation in the interstitial subnucleus, the ventrolateral subnucleus, the commissural subnucleus of the nucleus tractus solitarius, the lateral tegmental field of the reticular formation, the area postrema and the nucleus ambiguus. Neither the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus, usually active for swallow, nor the nucleus retroambiguus, retrofacial nucleus, or the lateral reticular nucleus, usually active for cough, were active with elicitation of the laryngeal adductor response alone. The results demonstrate that the laryngeal adductor pathway is contained within the broader pathways for cough and swallow in the medulla.

Central pattern generators are contained in the medulla for many different complex behaviors such as breathing, coughing, swallowing, and vocalization. Each of these behaviors involves vocal fold movement in the larynx. During breathing, the vocal folds modulate airflow by increased opening during inspiration and a more medial position during expiration (Bartlett et al. 1973; Davis et al. 1993; England et al. 1982). For swallowing, laryngeal closing and elevation prevent aspiration (Gay et al. 1994; Kidder 1995) while for cough, tight vocal fold closure increases pulmonary pressure prior to forceful expiration to clear the airway (Widdicombe 1980). For vocalization during speech, the two vocal folds meet in the midline for vibration on expiratory flow (Titze 1994). During each of these behaviors, laryngeal movement is coordinated with patterns of respiration and deglutition. The laryngeal adductor response (LAR) is a simple response that only involves vocal fold closure and not the added movements that occur during cough or swallow (Ludlow et al. 1992). The LAR is thought to reflect the pathway involved in laryngospasm (Ikari and Sasaki 1980), and is evoked by single electrical stimuli to the superior laryngeal nerve (SLN) both in cats (Sasaki and Suzuki 1976; Sessle 1973b; Suzuki 1987) and awake humans (Ludlow et al. 1992).

More intense and prolonged stimulation of ISLN afferents will also elicit swallow and cough. Pharyngeal stimulation can initiate laryngeal closure and elevation for swallowing (Jean 1984) and stimulation of the laryngeal mucosa can initiate either a swallow, cough or the LAR (Gestreau et al. 1997; Nishino et al. 1996; Tanaka et al. 1995). Most of the laryngeal afferents are contained in the internal branch of the SLN (ISLN) (Yoshida et al. 1986) and project to the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) in mice (Astrom 1953), rats (Mrini and Jean 1995; Patrickson et al. 1991), cats (Kalia and Mesulam 1980a; Tanaka et al. 1987; Yoshida et al. 1982; Yoshida et al. 1986) and monkeys (Beckstead and Norgren 1979). The laryngeal efferent neurons are located in the nucleus ambiguus (NA) (Gacek 1975; Yoshida et al. 1982) in these species. The laryngeal adductor response pathway might involve some of the same interneurons between the NTS and the NA as those activated during cough and swallow (Gestreau et al. 1997; Harada et al. 2002; Jean 2001).

Mechanical stimulation of the epiglottis and arytenoids, can produce prolonged inspiration and laryngospasm, which can be life threatening in the clinical setting (Odom 1993). The frequency of repeated electrical stimulation may determine whether a swallow or a cough is produced with ISLN stimulation (Harada et al. 2002). Stimulation at 10–30 Hz produces fictive swallowing (Dick et al. 1993), while 2–10 Hz produces sneezing and coughing (Bolser 1991; Gestreau et al. 1997; Satoh et al. 1998), and 10–50 Hz produces respiratory slowing (Bongianni et al. 1988; Bongianni et al. 2000; Lawson 1981; Sutton et al. 1978). Changing both the rate and intensity of ISLN stimulation will alter the behavioral response (Miller and Loizzi 1974), as shown by monitoring the compound action potential from the nerve. During minimal stimulaiton to activate only the fastest conducting sensory fibers, inhibition of respiration began at 3.2 times threshold intensity and swallowing occurred at 8.4 times threshold when using low frequencies (e.g. 3 Hz). At high rates such as 30 Hz, respiratory slowing occurred at 2 times threshold intensity and swallowing occurred at 2.7 times threshold intensity during recruitment of the same group of axons. Dick et al., (1993) found interactions between breathing and swallowing with changes in SLN stimulation intensity and rate, and proposed that some part of the same neural pathways may be involved in each. Our interest is in which part of these pathways are involved when only the LAR is elicited. Because the LAR can be elicited using a single stimulus (Sasaki and Suzuki 1976), we used a very low rate of stimulation, 0.5 Hz, to prevent the occurrence of swallowing, cough and respiratory slowing. We also used a low stimulation intensity, supramaximal for eliciting just the LAR, to provide a similar stimulus intensity across animals.

One approach for studying functional brainstem pathways involves Fos immunocytochemistry. The protein product of the immediate early gene c-fos, is regarded as a marker for neuronal activation, and can map pathways with single cell resolution in the central nervous system (Sagar et al. 1988). Recent studies have used intense and prolonged electrical stimulation (5–10 Hz) of both the internal and external branches of the SLN to identify brain stem areas activated during swallowing in mice (Sang and Goyal 2001) and coughing in cats (Gestreau et al. 1997). In these studies, abdominal, oropharyngeal and esophageal muscles were active during cough or swallow. While both of these studies found neuronal activation in some common brainstem regions, certain regions showed neuronal activity during swallowing but not during coughing and vise versa. For example, the interstitial subnucleus of the NTS, (inTS), was activated in both studies while the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMV) was active only during swallowing. Although both studies used ISLN stimulation, the results indicated that different behavioral patterns and perhaps different brainstem regions were activated. Some of the same brainstem regions may be involved when the LAR is elicited by ISLN stimulation without the induction of cough or swallow.

The LAR is representative of laryngospasm which occurs during extubation when the endotracheal tube is pulled out from between the vocal folds producing intense stimulation of superior laryngeal nerve afferents under light anesthesia (Ikari and Sasaki 1980; Sasaki et al. 2001; Sasaki et al. 2003). This can produce a persistent contraction of the thyroarytenoid (TA) muscle that closes the vocal folds causing a life-threatening obstruction necessitating a tracheotomy (Mevorach 1996; Olsson and Hallen 1984; Ricard-Hibon et al. 2003). Prevention of laryngospasm can be provided by a bilateral block of the ISLN (Mevorach 1996). The incidence of laryngospasm is as high as 24% in some populations and is greater in children than in adults (Koc et al. 1998). This study is the first step in identifying the oligosynaptic pathway involved in this response. Once the neural pathways are identified future studies can begin to determine how to modulate the system to prevent laryngospasm.

This study also addresses the integrative system controlling the larynx. The central pattern generators for central apnea, laryngospasm, swallowing and cough can all be triggered by stimulation of the same laryngeal afferents. Identifying the neural substrates involved in each is a first step in beginning to identify possible differences between these systems. Although the same sensory triggers can elicit each pattern; the particular neural substrates involved may depend upon the spread of neuronal activation within the medulla with continued rapid and intense stimulation. In an initial study, continued tactile stimulation to the laryngeal vestibule induced Fos in the medulla oblongata in similar regions to swallow and cough in the cat (Tanaka et al. 1995). In that study however, the stimulation level was uncontrolled and no record was provided of which behaviors occurred.

To elicit the LAR alone, without cough or swallow, required close monitoring of a non-paralyzed animal throughout stimulation to assure that 1) the LAR was elicited consistently with each stimulus, and 2) only the laryngeal response was elicited and not the other potential behaviors of cough, swallow or respiratory slowing. By evoking the LAR, the laryngeal muscle contractions may induce additional stimulation in the larynx via the afferents in the ISLN. Shiba and his colleagues found laryngeal muscle activation feedback was abolished either by cutting the superior laryngeal nerve or by lidocaine applied to the laryngeal mucosa (Shiba et al. 1995; Shiba et al. 1997). Afferent feedback due to the elicitation of the LAR, therefore, would stimulate the same afferents as those being activated by electrical stimulation of the ISLN.

By using the same stimulation conditions across animals we could then identify which regions in the medulla were activated using Fos immunocytochemistry. Our hypothesis was that when the ISLN stimulation elicits the LAR alone, Fos expression would be induced only in some of the regions previously shown to express Fos during cough in the lower brainstem (Gestreau et al. 1997). Such a result would suggest that the pathways for laryngospasm only involve a subset of those evoking cough, swallowing and respiratory apnea and that future efforts at modulation of this system should address the neurotransmitter mechanisms within those particular regions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fifteen cats of either sex weighing between 2.5 and 5.0 kg were used in this study: ten were divided into 2 groups: group 1 (experimental, n=5), group 2 (sham operated control, n=5). Three additional cats (group 3) were used to evaluate if stimulation of the ISLN causes any electromyographic (EMG) responses in muscles other than the intrinsic laryngeal muscles, such as oral, pharyngeal and respiratory muscles. Two anesthetic controls were studied to determine the effects of anesthesia without the surgical procedures. All animals received humane care in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals prepared by the National Academy of Sciences and published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 86-23, revised 1985). Tissues from ten of these animals (groups 1 and group 2) were used in a related study (Ambalavanar et al. 1999).

Surgery and Electrical stimulation

Injection of Cholera toxin B

To demarcate the NA region that contains laryngeal efferent neurons, three days prior to the terminal procedure, a retrograde tracer, cholera toxin subunit B (ChTB), was injected into all the intrinsic laryngeal muscles of each cat on the right side in both groups 1 and 2. The animals were anesthetized with ketamine (25 – 30 mg/kg, iv) and butorphanol tartrate (Torbugesic, 0.3–0.4 mg/kg). The thyroid cartilage was exposed by a midline incision over the larynx. Injections of 1% ChTB (List Biological Laboratories Inc. Campbell, CA,) were made into the laryngeal muscles on the right side. The TA (2.5 μl) and lateral cricoarytenoid (2.0 μl) muscles were injected through the cricothyroid membrane, the cricothyroid (2.0 μl) muscle was injected under direct observation, and the posterior cricoarytenoid (2.0 μl) and interarytenoid (1.0 μl) muscles were injected through the mouth using a suspension laryngoscope. All injections were made on the right side using a microsyringe in each animal. An analgesic buprenorphine at 6 mg/kg and antibiotics ampicillin at 25 mg.kg/bid and gentamycin at 2 mg/kg bid were administered after the surgery.

Stimulation of the ISLN

Surgery and electrical stimulation were as described previously (Ambalavanar et al. 1999). All animals were anesthetized at the same time of day initially with ketamine (25 – 30 mg/kg) and xylazine hydrochloride (.5–1.0 mg/kg) and then maintained on alpha chloralose (40 mg/kg) to effect. Paw withdrawal reflexes were checked every 30 minutes to ensure that the animal was at an appropriate level of anesthesia. All of the cats except the two anesthetic controls were secured in a supine position with the neck extended and a tracheostomy cannula was inserted as low as possible to prevent stimulation in the subglottic region. The tracheostomy cannula was connected to the output of an anesthesia machine that supplied oxygen at a flow rate of 2 L/min. The animal was breathing spontaneously through the cannula; inspiration and expiration were under the animal’s respiratory control. An IV drip was used to maintain fluid volume throughout the study at the rate of 3 drops per minute; equivalent to 10 ml per hour. Heart rate was measured with a 5 Lead ECG monitor (SpaceLabs Medical). A femoral artery was cannulated to monitor blood pressure using a SpaceLabs Medical monitor and 175μl of arterial blood was collected at hourly intervals to measure blood O2 and CO2 and pH levels using a Bayer Diagnostics 865 blood gas machine. The blood pH was maintained between 7.2 and 7.4, pCO2 was maintained between 30 –50 mmHg and the pO2 was between 400 – 500 mmHg. Respiratory rates and end tidal CO2 were monitored using an endotracheal sensor connected to a Novametrix CO2SMO ETCO2/SpO2 monitor.

The same surgical and recording techniques were used for groups 1 and 2. Hooked wire EMG electrodes were inserted into both the left and right TA muscles through the cricothyroid membrane (Andreatta et al. 2002) and the ISLN was exposed and secured in a bipolar cuff electrode on the right side.

The cats in group 3 were used to examine the behavioral response in additional muscles at the same rate and intensity of ISLN stimulation. They had additional hooked wire electrodes inserted into the right and left cricothyroid (CT) laryngeal muscles, diaphragm (Diaph), superior constrictor (SC) in the posterior pharynx, masseter (M) and genioglossus (G) muscles to confirm that ISLN stimulation did not cause EMG activity in muscles other than the intrinsic laryngeal muscles (Ambalavanar et al. 1999).

Group 1 and 2 were kept resting under anesthesia for 4h without stimulation after surgery to reduce Fos expression due to handling and surgery. In the experimental animals (groups 1 and 3) a single 0.2 ms pulse was delivered starting at a low level around 0.2 V using a Grass S-88 stimulator. The voltage was gradually increased until threshold was reached for producing an LAR in the ipsilateral TA. The level was then gradually increased while monitoring the LAR on a spike triggered oscilloscope until the amplitude of the first peak of the LAR remained the same despite further increases in the stimulation level, demonstrating a supramaximal level of stimulation. A short stimulus duration of 0.2 ms was used to limit the stimulus effects (Miller and Loizzi 1974). The threshold levels for eliciting the ipsilateral LAR were usually around 0.4 V and the supramaximal levels were usually about two times threshold, around .8 to 1.0 V.

During the 60 minutes of single stimuli to the ISLN every 2 seconds (0.5 Hz) the ipsilateral LAR was closely monitored on an oscilloscope to assure a consistent response. The animal was also closely observed to assure that a consistent LAR was elicited and that no other changes such as respiratory slowing, coughing or swallowing occurred. We selected the rate of 0.5 Hz as a result of previous experience that no change in respiratory cycle duration occurs when stimulation rates are between 0.5 and 1 Hz (Ludlow and Luschei 1997; Tanaka et al. 1995) and because Suzuki reported that 3 Hz was the minimum rate when respiration was first influenced (Suzuki 1987). These stimuli produced a bilateral adductor response in the TA muscles but did not alter respiration, or blood gas levels for 60 minutes which were checked again at the end of the stimulation period. No swallowing behavior or coughing was induced during stimulation at this low rate. The control animals in group 2 were not stimulated but rested during this period. The anesthetic controls were maintained on alpha chloralose without surgery for the same duration. In the experimental group 1 animals, the animal was grounded and muscle recordings were amplified using Grass physiological J10 amplifiers. The signals were band pass filtered between (30 –3000 Hz) and amplified between 1000 and 2000 times before being displayed on a Tektronix TDS scope (Ambalavanar et al. 2002; Ambalavanar et al. 1999; Andreatta et al. 2002). The LAR in the ipsilateral TA was displayed using a stimulation spike triggered display so that the amplitude of the initial peak of each response could be monitored. Three animals in group 3 were studied to examine muscle responses in several additional muscles: the right and left TA, CT, SC, M, and G muscles. Signals were displayed on the Tektronix TDS scope in free run mode before and after stimulation and simultaneously recorded on a multiple channel TEAC FM instrumentation recorder.

Tissue preparation and immunohistochemistry

Thirty minutes after the completion of either stimulation (group 1), or resting (group 2), the cats were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital (100 mg/kg, i.p) and perfused transcardially with 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) followed by a mixture of 2% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% picric acid in 0.1M phosphate buffer (PB, pH 7.4). The brains and larynges of these 12 animals were removed, post fixed overnight in the same fixative at 4ºC and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in PB for 48h at 4ºC.

Serial 50 μm transverse frozen sections were made through the medulla oblongata and larynx. From the medulla oblongata odd numbered sections were immunostained for Fos protein and even numbered sections for ChTB. The sections were washed well in PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 (PBST) and incubated in 0.1% H2O2 for 1 hour to inactivate the endogenous peroxidase activity. Odd numbered and even numbered sections were incubated in normal goat and rabbit serum respectively for one hour. Odd numbered sections were then incubated in rabbit antibody against Fos protein (Oncogene Science, Cambridge, MA. Ab-2, 1: 2500). Even numbered sections were incubated in goat anti-ChTB (List Biological Laboratories Inc. Campbell, CA, 1: 7000) in PBST for two days at 4°C. Following several washes in PBS, the sections from both groups were incubated in diluted biotinylated second antibody solution (ABC Elite kit, Vector Labs. Burlingame, CA 1:200) for 2 hours, then washed and incubated in ABC reagent for 1 hour at room-temperature. Bound antibody was visualized as a brown reaction product by incubating the sections in a solution containing 0.02%, 3.3 diaminobenzidine and 0.02% H2O2 for 10 minutes at room temperature. They were then washed and mounted on chrome-alum-gelatin coated slides. ChTB stained sections were photographed and then counterstained with cresyl-fast violet. Sections from the larynx were immunostained for ChTB as described above and examined to confirm that the injected tracer was confined to the laryngeal muscles.

No immunoreactivity was found in immunohistochemical control sections treated in the same manner except that (a) the primary antibody was omitted, and (b) preabsorbed serum was used (1μg peptide / 1ml diluted antibody).

Quantification of Fos-Like Immunoreactive neurons

All quantification was conducted in sections from group 1 and group 2 animals without knowledge of the experimental history of the animals (blinded). Sections were examined at 40, 100 and 200 ×, using a light microscope and Fos-like immunoreactive (FLI) neurons were counted in sections that were 400 im apart from the level of the caudal end of the NTS to the level of the caudal end of the facial nucleus. Sections at identical rostrocaudal levels were chosen for quantification from both the experimental and control groups. The outline of each section and the location of FLI neurons was marked manually using an image analysis system (Neurolucida, MicroBrightField Inc. Colchester, VT). Anatomical landmarks of the NA and other brainstem structures were determined according to the description in Berman’s Atlas (Berman 1968) using adjacent Nissl stained sections also immunostained for ChTB. The subnuclei of the NTS were delineated as previously described (Ambalavanar et al. 1998) using Nissl stained sections. At the level of the area postrema (AP) a parvocellular nucleus (Ambalavanar et al. 1998; Loewy and Burton 1978) or subnucleus gelatinosa (Kalia and Mesulam 1980b) covers the dorsomedial border of the medial subnucleus of the NTS (MnTS). This subnucleus contains many glial cells and very small neurons with little Nissl substance. Only occasional FLI neurons occurred in this region, therefore we counted FLI neurons in the MnTS including this region of the NTS (see Gestreau et al., 1997). The marked FLI neurons were then automatically counted using the computer software program (Neurolucida, MicroBrightField Inc, Colchester, VT).

The number of FLI neurons in the experimental and control cats were compared statistically in 14 structures: commissural (ncom), dorsal (DnTS), ventrolateral (VlnTS), inTS and MnTS subnuclei of the NTS, lateral tegmental field of the reticular formation (FTL), NA, lateral reticular nucleus (LRN), DMV, AP, spinal trigeminal nucleus (5sp), vestibular nucleus (VN), retrofacial nucleus (RFN) and nucleus retroambiguus (RA). Each structure extends to a different distance rostrocaudally. The mean number of FLI neurons was calculated for each structure from counts done from between 3 and 20 sections (depending on its distribution rostrocaudally) that were 400 im apart, from the level of the caudal end of the NTS to the level of the caudal end of the facial nucleus.

Statistical analysis

The total cell counts within each of the 14 regions on the ipsilateral (right) and contralateral (left) sides were then computed for each animal. The mean number of sections counted for each structure on the right and left sides was the same for each of the groups. An initial analysis of variance compared the number of FLI neurons in the two groups as the main effect. Two repeated factors were examined within animals: first, the differences between regions and second, the differences between sides (ipsilateral versus contralateral to stimulation). Interactions between group and region and between group and side were also tested. When the initial ANOVA was significant, group comparisons were made on each of the 14 structures while also testing for a group by side interaction. Because group comparisons were being conducted for each of the 14 structures in addition to the original ANOVA, the criterion p value for these planned comparisons was adjusted using the Bonferroni procedure (.05/15 = .0033).

RESULTS

EMG response

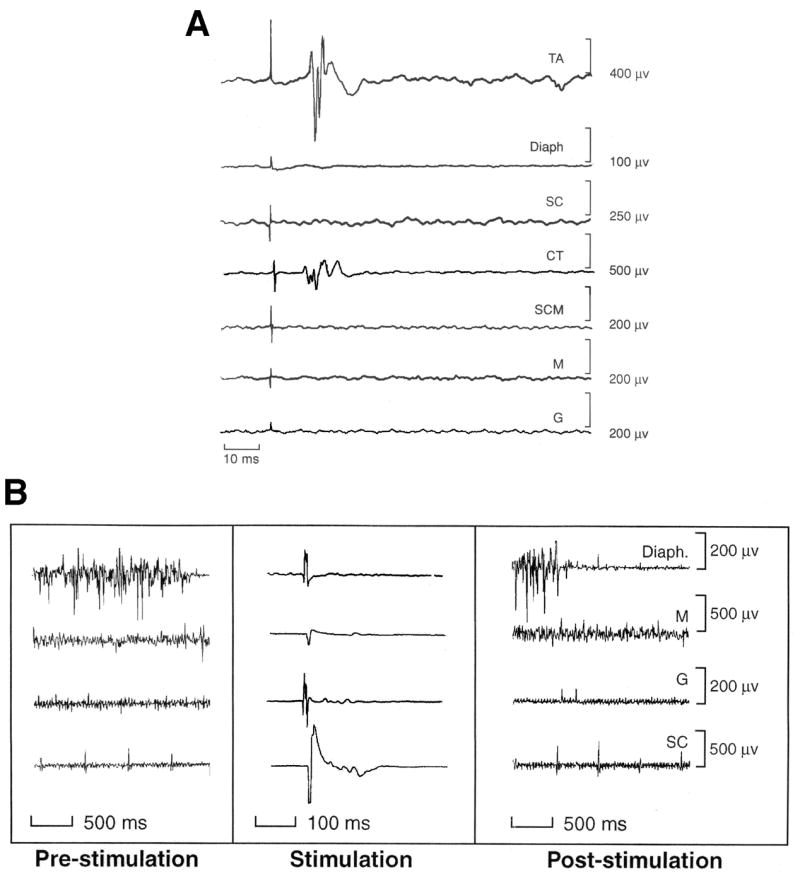

In group 1, ipsilateral TA muscle responses began 11.8 ms (range 10 to 14 ms) after the single stimulus to the ISLN. Synchronous responses were found in the CT, another intrinsic laryngeal muscle, (Figure 1A). Because the CT muscle acts to lengthen the vocal folds while the TA acts to shorten the vocal folds, a co-contraction of these two muscles results in an increase in vocal fold tension during vocal fold adduction (closure) (Titze et al. 1989). Contralateral TA responses occurred in 4 of the 5 experimental animals; the recurrent laryngeal nerve was tied in one animal and no response occurred in the contralateral TA. Two of the 4 had very small contralateral TA responses in contrast with the ipsilateral TA response while the other two had equivalent responses in the TA muscles on both sides. No responses to SLN stimulation were found in the Diaph, the SC, M, and G muscles, although these muscles showed either phasic or tonic spontaneous activity. The Diaph was phasically active during inspiration and quiet during expiration, the M had spontaneous activity and single unit firing was seen in the G and the SC (Figure 1B). None showed a reflex response similar to the TA or CT muscles in Figure 1A. In addition, no long-term changes in muscle activity were observed when the EMG signals were monitored on a Tektronix TDS scope during the experiment in the free run mode. Recordings made a half second before and after stimulation are shown in Figure 1B. At this slow rate of ISLN stimulation (.5 Hz) and low intensity (.6–.9 V) only the laryngeal muscle responses were observed and no patterns of swallow or cough.

Figure 1.

A. The average of over 114 responses to stimulation of the internal branch of the superior laryngeal at 2 s intervals (0.5 Hz) showing active responses only in the laryngeal muscles, the thyroarytenoid (TA) and the cricothyroid (CT) muscles at 10 ms on the same side as the stimulation. Simultaneous recordings from the diaphragm (Diaph), the superior constrictor of the pharyngeal wall (SC), the sternocleidomastoid (SCM), the masseter (M) and the genioglossus (G) on the same side show the absence of responses in muscles involved in swallow and cough. B. Examples of recordings of respiratory and swallowing muscles (Diaph.=diaphragm, M= masseter, G= genioglossus, and SC=superior constrictor) 2 s before (pre-stimulation), during the elicitation of the laryngeal adductor response (Stimulation) and 2 s after (Post-stimulation) to demonstrate that changes in muscle tone after with stimulation in comparison with before stimulation. Diaphragmatic activity is the phasic activity increasing with inspiration. The Stimulation panel shows averages of muscles responses to 114 stimulation trials at 0.5 Hz with stimulation artifact and no clear muscle response in contrast with the thyroarytenoid (TA) and cricothyroid (CT) muscle recordings in A. The spontaneous muscle activity is shown before and after stimulation for the diaphragm (Diaph), masseter (M), superior constrictor (SC) and genioglossus (G). None of these muscles show changes in background activity following ISLN stimulation.

Description of the Distribution of FLI Neurons

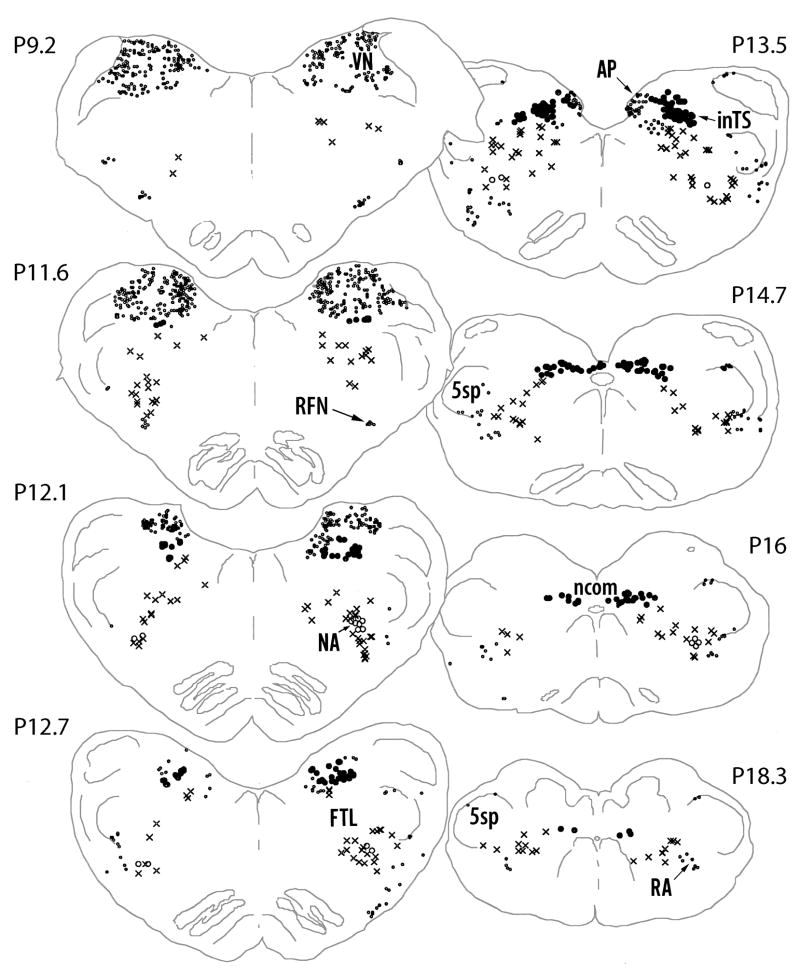

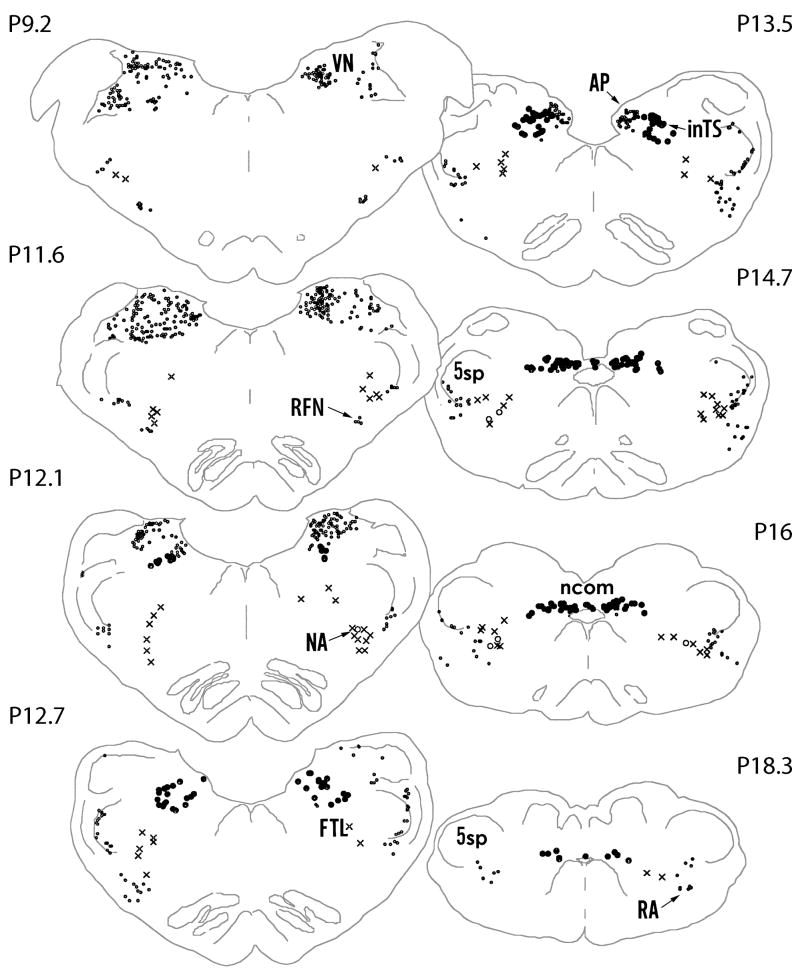

The distribution of FLI neurons in the regions of the medulla in representative animals of both the experimental and control groups are described here and the quantitative results for the groups are presented below. As shown in Neurolucida drawings (Figures 2 and 3), FLI neurons occurred in the NTS subnuclei in the experimental animal and not in the control at 13.5, while similar numbers of FLI neurons occurred in both animals in the VN, RFN and RA.

Figure 2.

Computer video drawings of representative sections through the medulla oblongata from a cat that had ISLN stimulation). The approximate rostrocaudal levels of the Berman’s atlas coordinates are marked on the figure (Berman 1968). AP - area postrema; S; FTL - lateral tegmental field of the reticular formation; inTS - interstitial subnucleus of the NTS;; ncom - commisural subnucleus of the NTS; NA - nucleus ambiguous; RA - retroambigual nucleus; RFN - retrofacial nucleus; VN - inferior vestibular nucleus;; 5sp - spinal trigeminal nucleus.

Figure 3.

Computer video drawings of representative sections through the medulla oblongata from an unstimulated cat (Control). The approximate rostrocaudal levels of the Berman’s atlas coordinates are marked on the figure (Berman 1968). AP - area postrema;; FTL - lateral tegmental field of the reticular formation; inTS - interstitial subnucleus of the NTS;; ncom - commisural subnucleus of the NTS; NA - nucleus ambiguous; RA - retroambigual nucleus; RFN - retrofacial nucleus; VN - inferior vestibular nucleus; ; 5sp - spinal trigeminal nucleus.

The Nucleus Tractus Solitarius

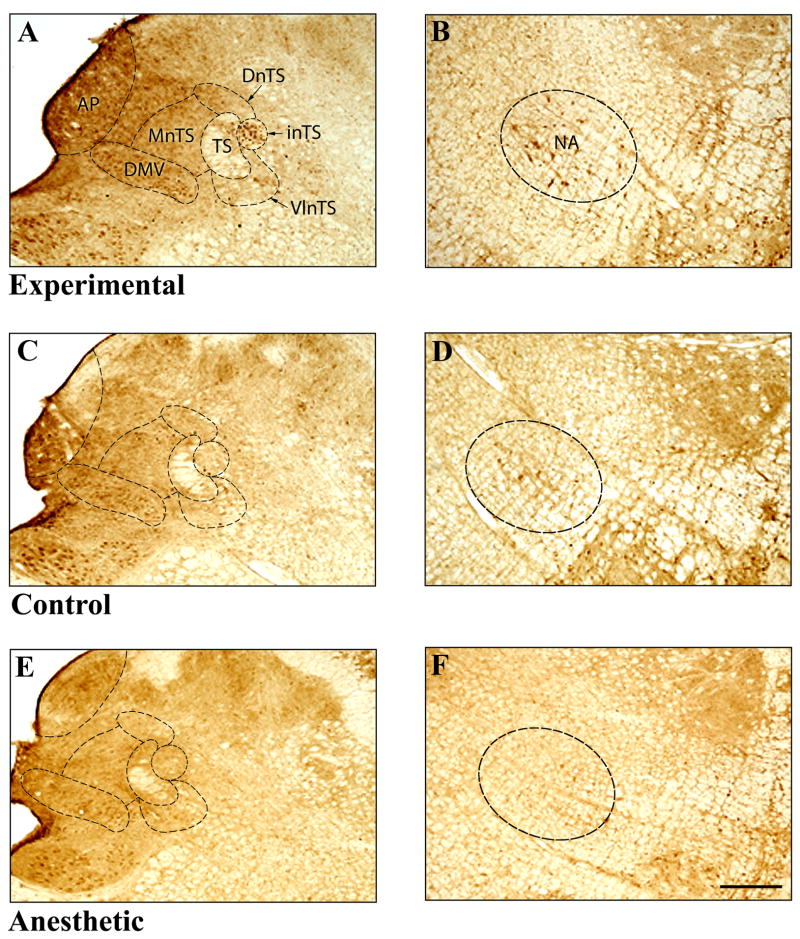

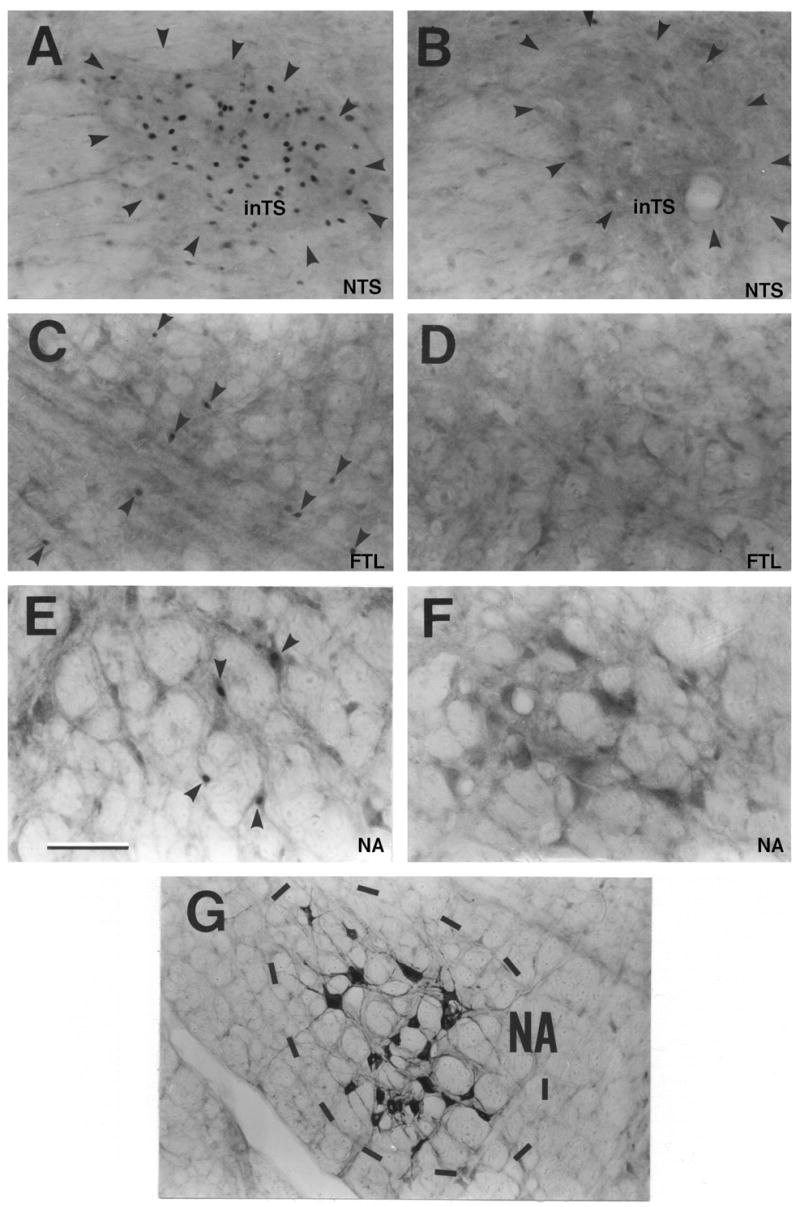

Most of the FLI neurons in the NTS were observed in the experimental animals between levels P13.5 and P9.5 of the Berman’s Atlas (1968) co-ordinates, i.e. between +3.6 mm +0.4 mm rostral to the obex, (Figure 2). In the NTS, a greater density of FLI neurons was found in the inTS than in any other subnuclei in the experimental group (Figure 4A). A dense cluster of FLI neurons was found in the inTS at the levels of the AP, between +0.4 and +1.2 mm rostral to the obex around the level P13.5 of the atlas co-ordinates (Figure 2, Figure 4A, Figure 5A). In contrast, very few FLI neurons were found in this region in the surgical controls (Figure 4C, Figure 5B) or in the anesthetic controls (Figure 4E). FLI neurons were also observed in the ncom from the level of the obex to the most caudal level of the NTS in both groups but the numbers were more numerous in the experimental animal than in the control (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 4.

Photomicrographs of a section through the brain stem at the level of the area postrema from an experimental (A, B), surgical control (C,D) and an anesthetic control (E,F) cat showing FLI neurons in different subnuclei of the NTS (A,C,E) and in the NA (B,D,F). Approximate boundaries of the subnuclei are shown by dotted lines. AP-area postrema, DMV – dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus, DnTS – dorsal subnucleus of the nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS),, NA - nucleus ambiguus, inTS - interstitial subnucleus of the NTS, MnTS medial subnucleus of the NTS, TS – solitary tract, VlnTS - ventrolateral subnucleus of the NTS.. Scale bar = 500μm.

Figure 5.

Fos-like immunoreactivity in the inTS (A, B), FTL (C, D) and the NA (E,F). Many FLI neurons can be seen in all three brain stem regions of the stimulated than the nonstimulated control cats. Laryngeal motor neurons retrogradely labeled in the NA are shown in G. (Scale bar = 100 μm).

In the anesthetic control (Figure 4E, 4F), only a few sparse FLI neurons were observed in the NTS, FTL, NA or LRN (between 0 and 3 FLI neurons/section) in contrast with the experimental animal in Figure 4A and Figure 4B.

The Nucleus Ambiguus

ChTB labeled neurons were found in the NA between the caudal end of the facial nucleus and the caudal end of the inferior olive mainly in the ventral part of the nucleus (Figure 5G). At the level of the rostral end of the hypoglossal nucleus, a cluster of ChTB labeled neurons were found in the ventromedial and the central parts. Although a few FLI neurons were observed in the NA in control cats (Figure 4D, Figure 5F), many FLI neurons were observed in the experimental cats in the NA bilaterally between the rostral end of the hypoglossal nucleus and the caudal portion of the inferior olivary nucleus (Figure 2, Figure 4A, Figure 5E).

The Lateral Tegmental Field

Both the experimental and control groups expressed FLI neurons in all sections in the FTL, however, the number of FLI neurons was more in the experimental group at all levels (Figures 2 and 3). More FLI neurons were found in the region between P11.6 and P14.7 of the atlas co-ordinates (Figure 2). Within the FTL, FLI neurons were greatest in the middle region bound laterally by the LRN and medially by the paramedian reticular nucleus in the experimental animal (Figure 2, Figure 4A and Figure 5C) in contrast with the surgical control (Figure 3, Figure 4C and Figure 5D). No FLI neurons, however, were found in the paramedian reticular nucleus (Figures 2 and 3).

Other nuclei

In other areas of the medulla oblongata many FLI neurons were consistently observed regardless of the stimulation (Figures 2 and 3). These areas included 5sp, VN and LRN. FLI neurons were also observed in AP, DMV, RFN and RA in both stimulated and non-stimulated control animals. Very few FLI neurons were observed in the anesthetic controls (Figure 4E).

No FLI neurons were found in the following regions in either the experimental or the surgical control group: the inferior olive, the gracile nucleus, the hypoglossal nucleus, the postpyramidal nucleus of the raphe, the magnocellular tegmental field, the gigantocellular tegmental field, the Bötzinger or the preBotzinger region (Figures 2, 3 and 4).

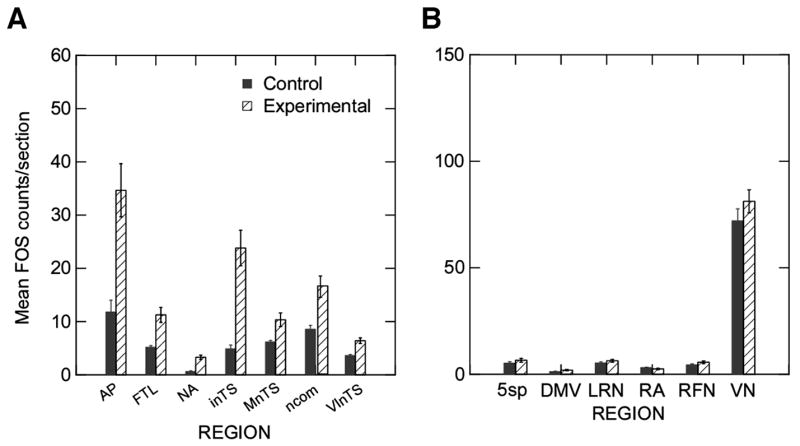

Quantitative Results and Statistical Analyses

The numbers of FLI neurons per section were counted in the experimental (group 1) and control (group 2) animals without knowledge of group identity. The numbers of sections counted per structure were the same in the two groups and varied from: 4 sections per side per animal within each group for the AP; between 6 and 7 for the InTS, RFN and ncom; between 9 and 12 for DnTS, VlnTS, MnTS, DMV, VN; and between 14 and 20 for LRN, NA, FTL, 5sp, and RA. The mean number of FLI neurons per section was then computed for each animal in each region on the right (ipsilateral) and left (contralateral to stimulation) sides. The mean counts were transformed into logarithms to normalize the distribution of the data before using a parametric statistical analysis procedure. The repeated measures ANOVA results (General Linear Model using SYSTAT version 10 statistical software) were significant for the group main effect (F=23.519, p=0.001). The within animals region differences in the numbers of FLI neurons was significant (F=128.83, p<0.0005) as was the region by group interaction (F=4.402, p<0.0005). The ipsilateral versus contralateral sides were not statistically significant (4.481, p=0.067) and the side by group interaction was also non-significant (F=2.232, p=0.174).

Post hoc F tests were conducted for each of the regions. Using the Bonferoni corrected p value for statistical significance (.05/15p<0.0033) significant differences were found in the numbers of FLI neurons between the experimental and control animals on the following structures: ncom (F=15.755, p=0.001), VlnTS (F=36.516, p<.0005), inTS (F=71.61, p<.0005), FTL (F=23.046, p<.0005), NA (F=19.094, p<.0005), and AP (F=22.817, p<.0005). Group differences showed a non-significant trend on MnTS (p=.008). The numbers of FLI neurons were greater in the experimental animals for each of these structures (Figure 6A). None of the side by group interactions approached statistical significance, demonstrating that the number of FLI neurons was similar on the ipsilateral and contralateral sides of the medulla. The FLI neurons were few in the other regions except the VN, which had equally high levels of FLI neurons in both groups (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Mean and standard errors in the number of FLI neurons counted for each structure in the control (Control) and the experimental (Experimental) groups. A provides the plots of the structures where the two groups differed significantly (p<.0033) or showed a trend towards a difference (MnTS, p=.008). Structures are AP= area postrema, FTL=lateral tegmental field, NA= nucleus ambiguus, inTS=interstitial subnucleus of the nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS), ncom= commissural subnucleus of the NTS, and the VlnTS= ventrolateral subnucleus of the NTS. B provides plots of the other structures which did not differ between the two groups in the number of FLI neurons. Structures are 5sp=spinal trigeminal nucleus, DMV= dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus, LRN= lateral reticular nucleus, RA= retroambiguus, RFN= retrofacial nucleus, and VN=vestibular nucleus.

One experimental animal had no contralateral TA response, 2 had very small contralateral responses relative to their ipsilateral TA response, and 2 had equal responses on both sides. We examined whether there were side differences in the number of FLI neurons in regions between the cats with different contralateral TA muscle responses. The repeated measures ANOVA only included those regions which had significantly more FLI neurons in the experimental animals. No significant interaction was found between the number of FLI neurons ipsilateral versus contralateral to stimulation with the three contralateral TA response (F=0.647, p=0.607) and no interaction of side by muscle response by region was found (F=0.677, p=0.745).

DISCUSSION

In this study we identified brainstem regions involved in elicitation of a LAR (without the induction of cough or swallowing) based on immunohistochemical detection of FLI neurons following ISLN stimulation. This is the first demonstration of a LAR pathway that does not elicit neuronal activity in the caudal brainstem regions involved in cough (Gestreau et al. 1997), swallowing (Sang and Goyal 2001) or vocalization (Holstege 1989; Holstege and Ehling 1996; VanderHorst and Holstege 1996; Zhang et al. 1995; Zhang et al. 1992). During the study the animals were monitored to assure that only the LAR occurred. In addition, the rate of stimulation was well below 2–5 Hz, the minimal rate at which cough (Gestreau et al. 1997) or sneezing (Satoh et al. 1998) is induced, below 10 Hz the minimal rate at which swallowing will be induced (Dick et al. 1993), and below 20 Hz the usual rate to induce respiratory slowing or apnea (Abu-Shaweesh et al. 2001; Bongianni et al. 1988; Bongianni et al. 1996; Bongianni et al. 2000; Mutolo et al. 1995). Short, low level electrical ISLN pulses at a slow rate (0.5 Hz) elicited selective bilateral laryngeal muscle responses without coughing or swallowing. The superior laryngeal nerve contains 75% Group III A-delta fibers with some Group II A-alpha fibers and relatively few unmyelinated fibers (Miller and Loizzi 1974). Miller and Loizzi concluded that the larger A-alpha fibers contributed to the initial action potential invoked with electrical stimulation of the ISLN. They also concluded that these larger fibers were involved in the reflexive changes in respiration and swallowing because the effects of stimulation on these functions were much greater at more rapid rates of stimulation such as 30/s. Because we were only stimulating at low rates 0.5/s but at supramaximal levels for invoking the LAR, our stimuli likely activated both the A-alpha and the more numerous A-delta fibers. Perhaps the smaller Group III A-delta fibers play a role in evoking the LAR in addition to the larger Group II A-alpha fibers which can evoke respiratory slowing and swallowing with ISLN stimulation (Miller and Loizzi 1974).

An alternative explanation may be that with prolonged rapid intense stimulation such as that used in studies to elicit swallowing or cough, there is spread of neuronal activation to activate neurons in additional regions to invoke these more complex behaviors. This may explain why our low intensity and slow rate of stimulation may have only involved the LAR and not swallowing, coughing or respiratory slowing.

The LAR latencies found in our study (10–14 ms) are similar to those previously reported (Ikari and Sasaki 1980; Mochida 1990; Sasaki and Suzuki 1976) and suitable for mapping the pathway in the medulla oblongata. The response delay between the stimulus and the muscle response suggests that the pathway is oligosynaptic. Stimulation of the SLN elicits responses in the NTS between 1.7 ms and 3.5 ms in the cat (Biscoe and Sampson 1970; Porter 1963; Sessle 1973a) while stimulation in the vicinity of the NA, elicits muscle responses between 1.7 and 2.0 ms (Delgado-Garcia et al. 1983). Thus, a central processing time of 4.5 to 8.5 ms implies the presence of several interneurons between the NTS and the NA (Isogai et al. 1987).

Significant Fos activation in the brainstem

Although Fos immunocytochemistry is a powerful technique for the study of functional pathways of different systems (Dragunow and Faull 1989; Morgan et al. 1987; Sagar et al. 1988), neurons in some regions, however, do not express Fos (Dragunow and Faull 1989). Any absence of Fos in neurons, therefore, cannot be interpreted as a lack of neuronal activation, because hyperpolarizing or inhibitory conditions may not induce Fos. We could not determine, therefore, whether or not some neurons in the medulla were inhibited by ISLN stimulation.

In the NA the rostrocaudal extent of the ChTB labeled laryngeal adductor motor neurons was consistent with previous studies (Davis and Nail 1984; Gacek 1975; Lawn 1966; Yoshida et al. 1982). Because the form of cholera toxin used was inert, it did not cause motor neuron death. Therefore we were able to record the TA muscle response.

Both anatomical (Hamilton and Norgren 1984; Kalia and Mesulam 1980b; Lucier et al. 1986; Nomura and Mizuno 1983) and physiological studies (Bellingham and Lipski 1992; Jiang and Lipski 1992; Mifflin 1993; Sasaki and Suzuki 1976; Suzuki and Sasaki 1976) have examined the termination of laryngeal afferents in the medulla. The first order neurons are in the nodose ganglion and transmit sensory information from the larynx to second order neurons in the NTS. Within the NTS, laryngeal afferents terminate mainly in the inTS (Hamilton and Norgren 1984; Kalia and Mesulam 1980b; Lucier et al. 1986; Mrini and Jean 1995; Nomura and Mizuno 1983; Patrickson et al. 1991) while the MnTS, VlnTS and ncom subnuclei of the intermediate and caudal NTS also receive some terminals. Others have shown the neurons in the inTS and VlnTS are monosynaptically activated by laryngeal afferents (Bellingham and Lipski 1992; Jiang and Lipski 1992; Mifflin 1993). The close match between the topographic distribution of laryngeal afferent termination and the distribution of FLI neurons in the NTS found in our study, indicates that these are the second order neurons in the LAR pathway. A non-quantitative study of FLI neurons following tactile stimulation to the laryngeal mucosa, also revealed neuronal activation in the inTS and MnTS (Tanaka et al. 1995).

No ipsilateral predominance of FLI neurons occurred in the experimental group; similar increases were found bilaterally in the inTS, MnTS, FTL, ncom and VlnTS. Anatomical studies have shown ipsilateral projections of laryngeal afferent fibers onto the NTS subnuclei except for the ncom (Hamilton and Norgren 1984; Kalia and Mesulam 1980b; Lucier et al. 1986; Nomura and Mizuno 1983). The bilateral induction of FLI neurons in this study may have been due to bilateral TA muscle contractions deflecting the mucosa on both sides of the larynx in at least 2 of the 5 experimental animals. This was examined when we sub-grouped animals based on whether they had only an ipsilateral or both an ipsilateral and contralateral TA response. Because no relationship was found between the presence or relative amplitude of the contralateral TA response and the differences between ipsilateral and contralateral numbers of FLI neurons, the bilateral FLI neurons were probably not secondary to the contralateral TA muscle response. Sang and Goyal (2001), found increased FLI neurons bilaterally with ipsilateral predominance following SLN stimulation in mice during fictive swallowing. In an electrophysiological study, Sessle (1973), suggested that laryngeal afferents may terminate in adjacent regions such as the ncom subnucleus on the ipsilateral or contralateral sides, which then project directly or via interneurons to the contralateral NTS. Thus, the FLI neurons in the contralateral NTS in our study may also represent the effects of interneurons. Because the number of FLI neurons were similar on the two sides despite right ISLN stimulation, secondary interneurons of the NTS may be distributed bilaterally to the FTL and NA, probably via the axon collaterals (Otake et al. 1992).

One concern is whether neurons in the NTS and AP activated by electrical stimulation of the ISLN are specific to the LAR. Other cranial nerve afferents terminate in the InTS such as the glossopharyngeal nerve (Ootani et al. 1995) with convergence of afferents from the soft palate and pharynx occurring in this region (Altschuler et al. 1989). The genioglossus and superior constrictor, however, were not activated during the elicitation of the LAR in this study. It is also known that baroreceptor activation induces Fos in the medial, commissural and dorsolateral NTS subnuclei (Chan et al. 1998). Cardiovascular related inputs have also been reported to the caudal regions of the NTS (Ciriello et al. 1981). Furthermore, cardiovascular changes occur following high rates (10–20 Hz) of SLN afferent stimulation in dogs (Angell-James and Daly 1975; Kordy et al. 1975) and cats (Tomori and Widdicombe 1969). Perhaps the low rates of ISLN electrical stimulation used here prevented the activation of NTS neurons that normally respond to baroreceptor stimulation. Although some FLI neurons might be due to cardiovascular stimulation these should be few in number because the blood pressure was monitored and did not change with 0.5 Hz stimulation.

Although we found a high number of FLI neurons in the AP in both groups, the number was significantly greater in the experimental group. The AP receives sensory fibers from the vagus nerve (Beckstead and Norgren 1979; Ciriello et al. 1981; Kalia and Mesulam 1980a) and the NTS bilaterally with an ipsilateral predominance (Kalia and Mesulam 1980a; Morest 1967; Norgren 1978). There are no direct projections from the SLN to the AP (Nomura and Mizuno 1983), thus the FLI neurons in the AP may be due to heavy bilateral projections from the NTS. The AP is involved in cardiovascular regulatory function (Ferguson and Marcus 1988; Gatti et al. 1985), control of food intake (van der Kooy 1984), and chemoreceptive triggers for emesis in the cat (Belesin and Krstic 1986; Borison 1989). Because no cardiovascular effects or emesis responses were observed at the low rate of ISLN stimulation used here, the greater FLI neurons in the AP in the experimental group may represent secondary interneurons involved in the LAR.

Both the experimental and control animals were maintained on 100% oxygen and consequently had arterial O2 pressures between 400 and 500 mm Hg similar to others using hyperoxia with or without chloralose anesthesia (Eldridge and Kiley 1987; Miller and Tenney 1975). The animals in this study maintained a normal spontaneous breathing rate similar to previous reports of secondary return to air-breathing respiration levels when hyperoxia is maintained over 5 minutes (Leiter and Tenney 1986). This long term secondary effect of hyperoxia is thought to be due to some excitation in the ventrolateral medulla (Eldridge and Kiley 1987; Miller and Tenney 1975), although FLI neurons were not prominent in these regions in either group.

Fos expression in both the stimulated and unstimulated control groups

Similar numbers of FLI neurons were observed in both the experimental and control groups in the VN and the 5sp. The same finding was reported by Gestreau et al. (1997). This may be a result of surgically induced nociceptive inputs. Although some SLN afferents project to 5sp (Hamilton and Norgren 1984; Nomura and Mizuno 1983), Lucier et al. (1986) did not find any direct projections from ISLN to 5sp. The lack of enhanced numbers of FLI neurons in 5sp following ISLN stimulation here is similar to Gestreau et al. (1997) who used SLN stimulation to induce cough. This suggests a lack of direct projections from the ISLN to 5sp in the LAR pathway.

Relationship of Results to Diverse Laryngeal Functions

The pattern of induced FLI neurons during the LAR had some overlap and some differences from that previously reported during cough, swallowing and vocalization. Enhanced numbers of FLI neurons were found in the FTL in this study. Respiratory and swallowing-related neurons are present in the medullary reticular formation (Amri and Car 1988; Batsel 1964; Bianchi 1971; Ezure et al. 1993; Kessler and Jean 1985; Merill 1970; Vibert et al. 1976). Respiratory-related neurons are found along the vagal rootlets (Vibert et al. 1976) and in the RA, in close vicinity of the RFN. However, we did not find significant increases in FLI neurons in these regions. Possibly this is because the respiratory rhythm is influenced only when the SLN stimulation is greater than 3 Hz (Suzuki 1987) and we stimulated the ISLN at 0.5 Hz. Thus, the enhanced numbers of FLI neurons in the FTL in our study indicates that some of these neurons are involved in the LAR pathway.

Rapid SLN stimulation used by others to induce cough in cats resulted in FLI neurons in the medial FTL, LRN, RA, RFN and para-ambiguual regions (Gestreau et al. 1997). None of these regions showed significant enhancement of FLI neurons, except the FTL, in our study. This suggests differences in the LAR pathway from that for the cough reflex, with some overlap in the FTL.

The RA, a premotor region in the caudal part of the medulla, is thought to play a critical role in the mediation of vocalization based on physiological (Zhang et al. 1995; Zhang et al. 1992) and neuroanatomical evidence (Holstege 1989; Holstege and Ehling 1996; VanderHorst and Holstege 1996). The lack of significant numbers of FLI neurons in the RA in our study indicates that the LAR may not involve those brainstem regions controlling laryngeal function during vocalization.

The medullary reticular formation and NA are thought to be involved in patterning for swallowing (Jean 2001, 1984). A recent study using rapid continuous SLN stimulation to induce swallowing in mice (Sang and Goyal 2001), reported increased numbers of FLI neurons in the parvocellular reticular formation, all divisions of the NA and the DMV. Although direct comparisons cannot be made between our data in cats with their findings in mice, the distribution of FLI neurons differs substantially in the two studies. During swallowing, the posterior pharynx, tongue and esophagus are involved in the patterned muscle response. In addition, afferent stimulation of the glottis is increased as the vocal folds close to prevent substances from entering the airway (Widdicombe 1980, 1995). This might explain why increased numbers of FLI neurons occurred in additional regions of the brainstem during swallowing from those we found while evoking only the LAR. No increase in FLI neurons was found in the DMV and the FLI neurons in the reticular formation were mainly along the axons of the NA motor neurons and not in the parvocellular reticular formation in this study (Figure 5). Further, within the NA, the distribution of FLI neurons in our study was restricted to the rostrocaudal extent of laryngeal motor neuron distribution.

In conclusion, stimulation of the SLN afferents can evoke a variety of responses such as coughing, gagging, swallowing, laryngeal spasms, bronchoconstriction, apnea and retching. The type of reflex response evoked depends on the stimulus parameters used (Bellingham and Lipski 1992; Gestreau et al. 1997; Lucier et al. 1979; Sang and Goyal 2001; Sessle et al. 1978). Following SLN stimulation to evoke the LAR (this study), cough (Gestreau et al. 1997) and swallowing (Sang and Goyal 2001), FLI neurons are induced in certain brainstem regions such as the inTS, FTL and NA indicating that these different reflex responses use overlapping neural circuits. In contrast, differences in FLI neurons are also striking in each one of these types of responses. For example, swallowing involves neurons in the MnTS, DMV and all the subdivisions of the NA while cough reflex involves RA, RFN and LRN in addition to the inTS, FTL and NA. These areas (MnTS, DMV, RA, RFN, LRN) did not show FLI neurons in our study when only a LAR was evoked. Together, these studies indicate that the neural circuits involved in the different reflex responses are overlapping but separate.

In summary, we have identified the brainstem regions that are active during the elicitation of a simple LAR. In addition, we have demonstrated that the elicitation of this reflex does not involve all the brainstem regions previously found active during cough, swallowing or vocalization. Other laryngeal functions such as those involved in swallowing (Barkmeier et al. 2000) and vocalization (Davis et al. 1993; Sakamoto et al. 1993; Shiba et al. 1995; Zhang et al. 1994) may modulate the LAR. Further, abnormal reflex responses have been reported in patients with adductor spasmodic dysphonia (Ludlow et al. 1995) and occur during laryngospasm following extubation—a life threatening complication of anesthesia. Future neurochemical characterization of the FLI neurons identified in our study, using double labeling immunocytochemistry, could provide important information on how this vital reflex pathway may be modulated.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the advice of Dr. Paul Smith, Department of Mathematical Statistics, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland. Supported by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Z01 NS002980-4 MNB

References

- Abu-Shaweesh JM, Dreshaj IA, Haxhiu MA, Martin RJ. Central GABAergic mechanisms are involved in apnea induced by SLN stimulation in piglets. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:1570–1576. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.4.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschuler SM, Bao XM, Bieger D, Hopkins DA, Miselis RR. Viscerotopic representation of the upper alimentary tract in the rat: sensory ganglia and nuclei of the solitary and spinal trigeminal tracts. J Comp Neurol. 1989;283:248–268. doi: 10.1002/cne.902830207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambalavanar R, Ludlow CL, Wenthold RJ, Tanaka Y, Damirjian M, Petralia RS. Glutamate receptor subunits in the nucleus of the tractus solitarius and other regions of the medulla oblongata in the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1998;402:75–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambalavanar R, Purcell L, Miranda M, Evans F, Ludlow CL. Selective suppression of late laryngeal adductor responses by N-Methyl-D-Asparate receptor blockade in the cat. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:1252–1262. doi: 10.1152/jn.00595.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambalavanar R, Tanaka Y, Damirjian M, Ludlow CL. Laryngeal afferent stimulation enhances fos immunoreactivity in periaqueductal gray in the cat. J Comp Neurology. 1999;409:411–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amri M, Car A. Projections from the medullary swallowing center to the hypoglossal motor nucleus: a neuroanatomical and electrophysiological study in sheep. Brain Res. 1988;441:119–126. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91389-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreatta RD, Mann EA, Poletto CJ, Ludlow CL. Mucosal afferents mediate laryngeal adductor responses in the cat. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:1622–1629. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00417.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angell-James JE, Daly MB. Some aspects of upper respiratory tract reflexes. Acta Otolaryngol. 1975;79:242–252. doi: 10.3109/00016487509124680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astrom KE. On the central course of afferent fibers in the trigeminal, facial, glossopharyngeal, and vagal nerves and their nuclei in the mouse. Acta PhysiolScandSuppl. 1953;29(106):209–320. [Google Scholar]

- Barkmeier JM, Bielamowicz S, Takeda N, Ludlow CL. Modulation of laryngeal responses to superior laryngeal nerve stimulation by volitional swallowing in awake humans. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:1264–1272. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.3.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett DJ, Remmers JE, Gautier H. Laryngeal regulation of respiratory airflow. Respir Physiol. 1973;18:194–204. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(73)90050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batsel HL. Localization of bulbar respiratory center by microelectrode sounding. Exp Neurol. 1964;9:410–426. [Google Scholar]

- Beckstead RM, Norgren R. An autoradiographic examination of the central distribution of the trigeminal, facial, glossopharyngeal, vagal nerves in the monkey. J Comp Neurology. 1979;184:455–472. doi: 10.1002/cne.901840303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belesin DB, Krstic SK. Dimethylphenylpiperazinium-induced vomiting: Nicotinic mediation in area postrema. Brain Research Bulletin. 1986;16:5–10. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(86)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellingham MC, Lipski J. Morphology and electrophysiology of superior laryngeal nerve afferents and postsynaptic neurons in the medulla oblongata of the cat. Neuroscience. 1992;48:205–216. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90349-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman AL. A cytoarchitecture atlas with stereotaxic coordinates. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press; 1968. The brain stem of the cat. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi AL. The localization and study of medullary respiratory neurons: Antidromic activation by spinal cord and vagus stimulation. J Physiol (Paris) 1971;63:5–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biscoe TJ, Sampson SR. Responses of cells in the brain stem of the cat to stimulation of the sinus, glossopharyngeal, aortic and superior laryngeal nerves. Jphysiol. 1970;209:359–373. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolser DC. Fictive cough in the cat. J Appl Physiol. 1991;71:2325–2331. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.6.2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongianni F, Corda M, Fontana G, Pantaleo T. Influences of superior laryngeal afferent stimulation on expiratory activity in cats. J Appl Physiol. 1988;65:385–392. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.65.1.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongianni F, Fontana GA, Mutolo D, Pantaleo T. Effects of central chemical drive on poststimulatory respiratory depression of laryngeal origin in the adult cat. Brain Res Bull. 1996;39:267–273. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(95)02139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongianni F, Mutolo D, Carfi M, Fontana GA, Pantaleo T. Respiratory neuronal activity during apnea and poststimulatory effects of laryngeal origin in the cat. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:917–925. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.3.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borison HL. Area postrema: Chemoreceptor circumventricular organ of the medulla oblongata. ProgNeurobiol. 1989;32:351–390. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(89)90028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan JY, Chen WC, Lee HY, Chan SH. Elevated Fos expression in the nucleus tractus solitarii is associated with reduced baroreflex response in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1998;32:939–944. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.5.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciriello J, Hrycyshyn AW, Calaresu FR. Glossopharyngeal and vagal afferent projections to the brain stem of the cat: A horseradish peroxidase study. J Auton Nerv Sys. 1981;4:63–79. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(81)90007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis PJ, Bartlett D, Luschei ES. Coordination of the respiratory and laryngeal systems in breathing and vocalization. In: Titze IR, editor. Vocal Fold Physiology. San Diego: Singular Publishing Group, Inc.; 1993. pp. 189–226. [Google Scholar]

- Davis PJ, Nail BS. On the location and size of laryngeal motoneurons in the cat and rabbit. JCompNeurol. 1984;230:13–32. doi: 10.1002/cne.902300103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Garcia JM, Lopez-Barneo J, Serra R, Gonzalez-Baron S. Electrophysiological and functional identification of different neuronal types within the nucleus ambiguus. Brain Res. 1983;277:231–240. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90930-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick TE, Oku Y, Romaniuk JR, Cherniack NS. Interaction between central pattern generators for breathing and swallowing in the cat. J Physiol. 1993;465:715–730. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragunow M, Faull R. The use of c-fos as a metabolic marker in neuronal pathway tracing. JNeuronsciMethods. 1989;29:261–265. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(89)90150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge FL, Kiley JP. Effects of hyperoxia on medullary ECF pH and respiration in chemodenervated cats. Respir Physiol. 1987;70:37–49. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(87)80030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England SJ, Bartlett DJ, Daubenspeck JA. Influence of human vocal cord movements on air flow and resistance during eupnea. JApplPhysiol. 1982;52:773–779. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.52.3.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezure K, Oku Y, Tanaka I. Location and axonal projection of one type of swallowing interneurons in cat medulla. Brain Res. 1993;632:216–224. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91156-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson AV, Marcus P. Area postrema stimulation induced cardiovascular changes in the rat. AmJPhysiol. 1988;255:R855–R860. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1988.255.5.R855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gacek RR. Localization of laryngeal motor neurons in the kitten. Laryngoscope. 1975;86:1841–1861. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197511000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatti PJ, Souza JD, Taveira Da Silva AM, Quest JA, Gillis RA. Chemical stimulation of the area postrema induces cardiorespiratory changes in the cat. Brain Res. 1985;346:115–123. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91100-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay T, Rendell JK, Spiro J. Oral and laryngeal muscle coordination during swallowing. Laryngoscope. 1994;104:341–349. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199403000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gestreau C, Bianchi AL, Grelot L. Differential brainstem fos-like immunoreactivity after laryngeal-induced coughing and its reduction by codeine. J Neurosc. 1997;17:9340–9352. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-23-09340.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton RB, Norgren R. Central projections of gustatory nerves in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1984;222:560–577. doi: 10.1002/cne.902220408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada H, Sakamoto T, Kita S. Role of GABAergic control of swallowing and coughing movements induced by the superior laryngeal stimulation in cats. Society for Neuroscience; Orlando, Florida. Washington, D.C.: Society for Neuroscience; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Holstege G. Anatomical study of the final common pathway for vocalization in the cat. JCompNeurol. 1989;284:242–252. doi: 10.1002/cne.902840208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holstege G, Ehling T. Two motor systems involved in the production of speech. In: Davis PJ, Fletcher NH, editors. Vocal Fold Physiology: Controlling complexity and chaos. San Diego: Singular Publishing Group; 1996. pp. 153–169. [Google Scholar]

- Ikari T, Sasaki CT. Glottic closure reflex: Control mechanisms. Ann Otol. 1980;89:220–224. doi: 10.1177/000348948008900305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isogai YM, Suzuki M, Saito S. Brainstem response evoked by the laryngeal reflex. In: Hirano M, Kirchner JA, Bless DM, editors. Neurolaryngology: recent advances. Boston: College-Hill Press; 1987. pp. 167–183. [Google Scholar]

- Jean A. Brain stem control of swallowing: neuronal network and cellular mechanisms. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:929–969. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jean A. Control of the central swallowing program by inputs from the peripheral receptors. A review. J AutonNerv Syst. 1984;10:225–233. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(84)90017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C, Lipski J. Synaptic inputs to medullary respiratory neurons from superior laryngeal afferents in the cat. Brain Res. 1992;584:197–206. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90895-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia M, Mesulam MM. Brain stem projections of sensory and motor components of the vagus complex in the cat: I. The cervical vagus and nodose ganglion. J Comp Neurol. 1980a;193:435–465. doi: 10.1002/cne.901930210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia M, Mesulam MM. Brain stem projections of sensory and motor components of the vagus complex in the cat: II. Laryngeal, tracheobronchial, pulmonary, cardiac and gastrointestinal branches. JCompNeurol. 1980b;183:467–508. doi: 10.1002/cne.901930211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler JP, Jean A. Identification of the medullary swallowing regions of the rat. ExpBrain Res. 1985;57:256–263. doi: 10.1007/BF00236530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidder TM. Esophago/pharyngo/laryngeal interrelationships: airway protection mechanisms. Dysphagia. 1995;10:228–231. doi: 10.1007/BF00431414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koc C, Kocaman F, Aygenc E, Ozdem C, Cekic A. The use of preoperative lidocaine to prevent stridor and laryngospasm after tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;118:880–882. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(98)70290-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kordy MT, Neil E, Palmer JF. The influence of laryngeal afferent stimulation on cardiac vagal responses to carotid chemoreceptor excitation. J Physiol. 1975;247:24P–25P. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawn AM. The localization, in the nucleus ambiguus of the rabbit, of the cells of origin of motor nerve fibers in the glossopharyngeal nerve and various branches of the vagus nerve by means of retrograde degeneration. JCompNeurol. 1966;127:293–306. doi: 10.1002/cne.901270210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson EE. Prolonged central respiratory inhibition following reflex-induced apnea. J Appl Physiol. 1981;50:874–879. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1981.50.4.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiter JC, Tenney SM. Hyperoxic ventilatory responses of high altitude acclimatized cats. Respir Physiol. 1986;65:365–378. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(86)90020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewy AD, Burton H. Nuclei of the solitary tract: Efferent projections to the lower brain stem and spinal cord of the cat. JCompNeurol. 1978;181:421–450. doi: 10.1002/cne.901810211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucier GE, Egizii R, Dostrovsky JO. Projections of the internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve of the cat. Brain Res Bull. 1986;16:713–721. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(86)90143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucier GE, Storey AT, Sessle BJ. Effects of upper respiratory tract stimuli on neonatal respiration: reflex and single neuron analyses in the kitten. Biol Neonate. 1979;35:82–89. doi: 10.1159/000241157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow CL, Luschei ES. The effects of laryngeal afferent stimulaiton on respiration and laryngeal closure. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 1997;23:2100. [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow CL, Schulz GM, Yamashita T, Deleyiannis FW. Abnormalities in long latency responses to superior laryngeal nerve stimulation in adductor spasmodic dysphonia. Ann Otol RhinolLaryngol. 1995;104:928–935. doi: 10.1177/000348949510401203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow CL, VanPelt F, Koda J. Characteristics of late responses to superior laryngeal nerve stimulation in humans. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1992;101:127–134. doi: 10.1177/000348949210100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merill EG. The lateral respiratory neurons of the medulla: Their associations with nucleus ambiguus, nucleus retroambigualis, the spinal accessory nucleus and the spinal cord. Brain Res. 1970;24:11–28. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(70)90271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mevorach DL. The management and treatment of recurrent postoperative laryngospasm. Anesth Analg. 1996;83:1110–1111. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199611000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mifflin SW. Laryngeal afferent inputs to the nucleus of the solitary tract. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:R269–276. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.265.2.R269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AJ, Loizzi RF. Anatomical and functional differentiation of superior laryngeal nerve fibers affecting swallowing and respiration. Exp Neurol. 1974;42:369–387. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(74)90033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MJ, Tenney SM. Hyperoxic hyperventilation in carotid-deafferented cats. Respir Physiol. 1975;23:23–30. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(75)90068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochida A. Reflex control on laryngeal functions: Vibration effect of the laryngeal mucosa on recurrent laryngeal nerve reflexes. Journal of Otolaryngology of Japan. 1990;93:938–947. doi: 10.3950/jibiinkoka.93.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morest DK. Experimental study of the projections of the nucleus of the tratus solitarius and the area postrema in the cat. JCompNeurol. 1967;130:277–300. doi: 10.1002/cne.901300402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan JI, Cohen DR, Hempstead JL, Curran T. Mapping patterns of c-fos expression in the central nervous system after seizure. Science. 1987;237:192–197. doi: 10.1126/science.3037702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrini A, Jean A. Synaptic organization of the interstitial subdivision of the nucleus tractus solitarii and of its laryngeal afferents in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1995;355:221–236. doi: 10.1002/cne.903550206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutolo D, Bongianni F, Corda M, Fontana GA, Pantaleo T. Naloxone attenuates poststimulatory respiratory depression of laryngeal origin in the adult cat. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:R113–123. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.269.1.R113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino T, Tagaito Y, Isono S. Cough and other reflexes on irritation of airway mucosa in man. Pulm Pharmacol. 1996;9:285–292. doi: 10.1006/pulp.1996.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura S, Mizuno N. Central distribution of efferent and afferent components of the cervical branches of the vagus nerve. Anat Embryol. 1983;166:1–18. doi: 10.1007/BF00317941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norgren R. Projections from the nucleus of the solitary tract in the rat. Neuroscience. 1978;3:207–218. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(78)90102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odom JL. Airway emergencies in the post anesthesia care unit. NursClin North Am. 1993;28:483–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson GL, Hallen B. Laryngospasm during anaesthesia. A computer-aided incidence study in 136,929 patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1984;28:567–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1984.tb02121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ootani S, Umezaki T, Shin T, Murata Y. Convergence of afferents from the SLN and GPN in cat medullary swallowing neurons. Brain Res Bull. 1995;37:397–404. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(95)00018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otake K, Ezure K, Lipski J, Wong She RB. Projections from the commissural subnucleus of the nucleus of the solitary tract: an anterograde tracing study in the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1992;324:365–378. doi: 10.1002/cne.903240307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrickson JW, Smith TE, Zhou SS. Afferent projections of the superior and recurrent laryngeal nerves. Brain Res. 1991;539:169–174. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90702-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter R. Unit responses evoked in the medulla oblongata by vagus nerve stimulation. J Physiol. 1963;168:717–735. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1963.sp007218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricard-Hibon A, Chollet C, Belpomme V, Duchateau FX, Marty J. Epidemiology of adverse effects of prehospital sedation analgesia. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21:461–466. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(03)00095-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagar SM, Sharp FR, Curran T. Expression of c-fos protein in brain: Metabolic mapping at the cellular level. Science. 1988;240:1328–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.3131879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto T, Yamanaka Y, Wada K, Nakajima Y. Effects of tracheostomy on electrically induced vocalization in decerebrate cats. Neurosci Lett. 1993;158:92–96. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90620-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang Q, Goyal RK. Swallowing reflex and brain stem neurons activated by superior laryngeal nerve stimulation in the mouse. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;280:G191–200. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.2.G191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki CT, Ho S, Kim YH. Critical role of central facilitation in the glottic closure reflex. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2001;110:401–405. doi: 10.1177/000348940111000502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki CT, Jassin B, Kim YH, Hundal J, Rosenblatt W, Ross DA. Central facilitation of the glottic closure reflex in humans. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2003;112:293–297. doi: 10.1177/000348940311200401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki CT, Suzuki M. Laryngeal reflexes in cat, dog and man. Arch Otolaryngol. 1976;102:400–402. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1976.00780120048004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh I, Shiba K, Kobayashi N, Nakajima Y, Konno A. Upper airway motor outputs during sneezing and coughing in decerebrate cats. Neurosci Res. 1998;32:131–135. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(98)00075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessle BJ. Excitatory and inhibitory inputs to single neurones in the solitary tract nucleus and adjacent reticular formation. Brain Res. 1973a;53:319–331. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(73)90217-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessle BJ. Presynaptic excitability changes induced in single laryngeal primary afferent fibres. Brain Res. 1973b;53:333–342. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(73)90218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessle BJ, Greenwood LF, Lund JP, Lucier GE. Effects of upper respiratory tract stimuli on respiration and single respiratory neurons in the adult cat. Exp Neurol. 1978;61:245–259. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(78)90244-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiba K, Yoshida K, Miura T. Functional roles of the superior laryngeal nerve afferents in electrically induced vocalization in anesthetized cats. NeurosciRes. 1995;22:23–30. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(95)00877-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiba K, Yoshida K, Nakajima Y, Konno A. Influences of laryngeal afferent inputs on intralaryngeal muscle activity during vocalization in the cat. Neurosci Res. 1997;27:85–92. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(96)01136-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton D, Taylor EM, Lindeman RC. Prolonged apnea in infant monkeys resulting from stimulation of superior laryngeal nerve. Pediatrics. 1978;61:519–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M. Laryngeal reflexes. In: Hirano M, Kirchner JA, Bless DM, editors. Neurolaryngology: Recent Advances. Boston, MA: College-Hill; 1987. pp. 142–155. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Sasaki CT. Initiation of reflex glottic closure. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1976;85:382–386. doi: 10.1177/000348947608500309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Yoshida Y, Hirano M. Expression of Fos-protein activated by tactile stimulation on the laryngeal vestibulum in the cat’s lower brain stem. J Laryngol Otol. 1995;109:39–44. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100129196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Yoshida Y, Hirano M, Morimoto M, Kanaseki T. Distribution of sensory nerve fibers in the larynx and pharynx: An HRP study in cats. In: Hirano M, Kirchner JA, Bless DM, editors. Neurolaryngology: Recent advances. Boston, MA.: College-Hill; 1987. pp. 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Titze IR. Principles of Voice Production. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Titze IR, Luschei ES, Hirano M. Role of the thyroarytenoid muscle in regulation of fundamental frequency. Journal of Voice. 1989;3(3):213–224. [Google Scholar]

- Tomori Z, Widdicombe JG. Muscular, bronchomotor and cardiovascular reflexes elicited by mechanical stimulation of the respiratory tract. J Physiol. 1969;200:25–49. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1969.sp008680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kooy D. Area postrema: Site where cholecystokinin acts to decrease food intake. Brain Res. 1984;295:345–347. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90982-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderHorst VG, Holstege G. A concept for the final common pathway of vocalization and lordosis behavior in the cat. Prog Brain Res. 1996;107:327–342. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61874-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vibert JF, Bertrand J, Denavit-Saubie M, Hugelin A. Three-dimensional representation of bulbo-pontine respiratory networks architecture from unit density maps. Brain Res. 1976;114:227–244. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90668-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widdicombe JG. Mechanism of cough and its regulation. EurJ RespirDis Suppl. 1980;110:11–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widdicombe JG. Neurophysiology of the cough reflex. EurRespirJ. 1995;8:1193–1202. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08071193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y, Miyazaki T, Hirano M, Shin T, Kanaseki T. Arrangement of motoneurons innervating the intrinsic laryngeal muscles of cats as demosntrated by horseradish peroxidase. Acta Otolaryngologica. 1982;94:329–334. doi: 10.3109/00016488209128920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y, Tanaka Y, Hirano M, Nakashima T. Sensory innervation of the pharynx and larynx. Am J Med. 2000;108 Suppl 4a:51S–61S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00342-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y, Tanaka Y, Mitsumasu T, Hirano M, Kanaseki T. Peripheral course and intramucosal distribution of the laryngeal sensory nerve fibers of cats. Brain Research Bulletin. 1986;17:95–105. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(86)90165-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SP, Bandler R, Davis PJ. Brain stem integration of vocalization: role of the nucleus retroambigualis. J Neurophysiol. 1995;74:2500–2512. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.6.2500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SP, Davis PJ, Bandler R, Carrive P. Brain stem integration of vocalization: role of the midbrain periaqueductal gray. JNeurophysiol. 1994;72:1337–1356. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.3.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SP, Davis PJ, Carrive P, Bandler R. Vocalization and marked pressor effect evoked from the region of the nucleus retroambigualis in the caudal ventrolateral medulla of the cat. Neurosci Lett. 1992;140:103–107. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90692-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]