Abstract

An emerging alternative to traditional partner management for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) is expedited partner therapy (EPT), which involves the delivery of medications or prescriptions to STD patients for their partners without the clinical assessment of the partners.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently recommended EPT nationally in limited circumstances; however, its implementation may raise legal concerns. We analyzed laws relevant to the distribution of medications to persons with whom clinicians have not personally treated or established a relationship.

We determined that three fourths of states or territories either expressly permit EPT or do not expressly prohibit the practice. We recommend (1) expressly endorsing EPT through laws, (2) creating exceptions to existing prescription requirements, (3) increasing professional board or association support for EPT, and (4) supporting third-party payments for partners’ medications.

DESPITE MAJOR ADVANCES and achievements in the detection, treatment, and prevention of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) in the United States, infections such as chlamydia and gonorrhea remain significant public health challenges. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates (on the basis of data from 2000) that over 700 000 new cases of gonorrhea and 2.8 million new cases of chlamydia occur each year.1–3 To prevent reinfection and curtail further transmission, the CDC recommends that clinical management of patients with STDs should include treatment of the patients’ current sexual partners.4

Ensuring treatment of sexual partners has been a central component of STD prevention and control for decades.5,6 Initially developed to help control syphilis, partner management became widely recommended for gonorrhea, chlamydial infection, and HIV infection.7,8 However, with the exception of syphilis and sometimes HIV, partner management based on provider referral is rarely ensured for STDs, and patient referrals have only modest success in achieving partner treatment.9

An alternative public health approach is expedited partner therapy (EPT).3,10 EPT refers to the delivery of medications or prescriptions by persons infected with an STD to their sexual partners without prior clinical assessment of those partners. Clinicians (e.g., physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, pharmacists, public health workers) provide patients with sufficient medication, directly or with prescription, for them and their partners and encourage patients to have their partners seek clinical assessment. After evaluating multiple studies involving EPT, the CDC concluded that EPT is a “useful option” to promote partner treatment, particularly for male partners of women with chlamydial infection or gonorrhea.10 In August 2006, the CDC recommended EPT as an option for certain populations with specific conditions.4

Despite its endorsement, the CDC recognized numerous clinical factors or barriers to the practice of EPT, including (1) the potential for missed morbidity in partners who are treated without clinical evaluation, (2) concerns about adverse reaction to antibiotics,11,12 and (3) the need for coordinated, systematic efforts by public health authorities, private sector clinicians and agencies, pharmacies, health insurers, and community-based organizations. In addition, implementation of EPT may raise legal questions and concerns in some settings. Central to these concerns is the perceived unauthorized distribution of prescriptions or medications to partners with whom clinicians have not personally evaluated or established a physician–patient relationship. In 2005, Golden et al. surveyed state boards of medicine and pharmacy and found that most boards (88%) perceived EPT as illegal or of “uncertain” legality, in part because the legal issues have “simply never been addressed.”13(p114)

Beginning in September 2005, to assist state and local STD programs with EPT implementation efforts, we assessed the legal framework concerning EPT. Here, we discuss the legal issues underlying the practice of EPT, explain our methodology for the systematic examination of laws relevant to EPT, discuss major findings on the legality of EPT consistent with our examination, and provide legal and policy options for facilitating the implementation of EPT.

BACKGROUND

To implement EPT, potential legal barriers and concerns must be addressed. Providing access to prescription medications to persons whom a clinician has not examined or established a professional relationship may be viewed as illegal and unethical. Health care providers do not usually provide prescription medications to nonpatients. This basic tenet of health care services helps ensure that individuals do not gain access to medications they do not need or that could be dangerous to them. It is reflected in modern regulations limiting the distribution of medications over the Internet or through other electronic communications.14,15

There are, however, exceptions to the general rule. Physicians routinely provide prescription medications to children or elderly patients through parents or caregivers.16,17 Spouses or life partners may be given medications for existing patients. Medications for people with mental disabilities may be distributed through court-appointed guardians. Each year, public health practitioners provide flu vaccines without significant clinical evaluation to individuals who request it.18 In response to outbreaks of meningococcal meningitis in hospitals, hospital staff and their family members are provided antibiotics without advance clinical diagnosis. When the Food and Drug Administration approved the over-the-counter sale of the “morning after” contraceptive pill (Plan B) in 2006, it noted that the drug could be purchased by females or their male partners.19 Although each of these examples differs from EPT, they share a common purpose: ensuring that safe and effective medications are made available to people who need them, even without direct medical evaluation of the recipients. This is the same objective of EPT.

Still, health care practitioners may be concerned that they will be subject to sanctions (e.g., censure, fines, suspension, or license revocation) by state licensing boards or civil claims for malpractice for providing prescriptions to nonpatients. An array of licensing laws and provisions for different types of practitioners can lead to confusion as to their specific ability to practice EPT. State public health laws regulating STDs may condition treatment upon a clinical evaluation and diagnosis of an STD.20 These provisions bolster arguments that EPT violates acceptable clinical standards of care, at least until its practice is recognized as consistent with community standards of care. Clinicians’ fears of malpractice or other liability are real,21 even if there is minimal potential for a sexual partner to suffer serious side effects by taking antibiotics without prior examination.

Laws concerning the distribution of prescription medicines such as antibiotics may not bar EPT, but they can affect whether or how EPT is practiced. Pharmacists may be subject to separate disciplinary action if they dispense a prescription they have reason to know was given outside of a physician–patient relationship or without prior evaluation.22–24 Other practitioners may be prevented from dispensing (as contrasted with prescribing) drugs to a person who is not the practitioner’s patient.25,26 These provisions may forestall a practitioner from giving an “extra dose” of a medication directly to the patient for his or her partner. Some laws may require information (e.g., name, address) identifying the intended recipient on prescription orders or labels,27 which could be problematic if the patient does not want to disclose a partner’s identity.

METHODS

Against this backdrop of legal concerns, we assessed the legal status of EPT across the 50 states and other jurisdictions (District of Columbia, Puerto Rico). Our primary research objective was to identify legal provisions that affect a clinician’s ability to provide treatment for an STD patient’s sexual partner without prior evaluation of that partner. We examined 3 broad areas of legal relevance: (1) medical licensing and liability, (2) public health and safety, and (3) pharmaceutical practices, specifically laws concerning “legend” (i.e., prescription) drugs (excluding controlled substances).28

We first searched for laws that addressed all or part of the primary research objective and then interpreted the laws using accepted legal methods of statutory interpretation and weighing of authority to assess the legality of EPT in each jurisdiction.29 In each of the 3 major areas, we researched a spectrum of statutes, bills, administrative regulations and opinions, and judicial cases found through legal research engines (e.g., Westlaw, LexisNexis) and publicly available legal Web sites (e.g., those of the US Library of Congress, state legislatures, state attorney general’s offices, state judiciaries, and state health departments). Relevant search terms included physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and physician’s assistants (and other health care providers); public health; prescriptions; STDs; communicable diseases; authorization; treatment; physician–patient relationship; unauthorized practice; misconduct; and malpractice. Within each jurisdiction, these searches yielded numerous legal references, which we further culled to locate relevant laws related to the primary research objective. Secondary resources (e.g., reports, articles, media accounts) and informal discussions with select federal, state, and local lawmakers and policymakers, public health officials, and academics provided some information, which was confirmed through original legal research.

Legal information was organized by jurisdiction in a comprehensive table and a map that present summaries and citations of relevant laws and rulings concerning EPT.29 These include (1) existing statutes or regulations that specifically address the ability of authorized health care providers to provide a patient’s partner with a prescription for certain STDs without prior physician evaluation of that partner; (2) specific judicial decisions disciplining physicians for prescription practices that could implicate EPT; (3) administrative opinions by state attorneys general, actions by medical disciplinary boards, advisory decisions or resolutions of medical or pharmacy boards, or general policy guidelines that address EPT or the practice of prescribing without prior patient evaluation; (4) legislative bills or prospective regulations to authorize EPT that, although they have not been passed into law, provide insight into the potential legality of EPT; (5) laws that incorporate or adopt national guidelines that may endorse or support EPT (e.g., the CDC’s treatment guidelines for STDs,4 the American Public Health Association’s Control of Communicable Diseases Manual 30); and (6) prescription drug laws.

RESULTS

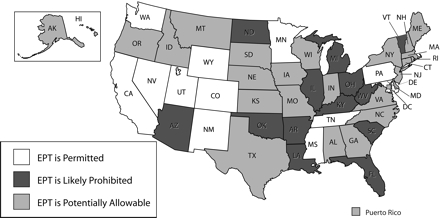

After creating a snapshot of each jurisdiction’s germane legal provisions, we then sought to determine the legality of EPT in each jurisdiction. Where statutory laws (or other primary laws) clearly permitted or prohibited EPT, determining legality was relatively straightforward. For the remainder, we employed sound principles to interpret ambiguous laws on the basis of their primacy (e.g., statutes take precedence over contrary policies), relevance (e.g., prescription drug laws concerning controlled substances were not referenced), and purpose (e.g., advisory opinions concerning distribution of drugs to third parties in non-EPT settings). We proffer the following conclusions (Figure 1 ▶), which are based on legal interpretation and subject to differing views.

FIGURE 1—

National assessment of the legal status of expedited partner therapy.

Expedited Partner Therapy Is Legally Permissible

EPT is legally permissible in 12 jurisdictions because their laws or governing authorities expressly allow the practice of EPT. California statutory law, for example, clearly authorizes EPT. A physician in California may “provide prescription antibiotic drugs to [a] patient’s sexual partner[s]. . . without examination of that patient’s partner[s]” for treating chlamydia, gonorrhea, or other STDs.31 Tennessee’s board of medical examiners promulgated administrative rules allowing EPT for the “effective and safe treatment to partners of patients infected with [chlamydial infection] who for various reasons may not otherwise receive appropriate treatment.”32 Subsequent to the CDC’s national recommendation, New Mexico amended its administrative code to permit EPT in accordance with the guidelines and protocols established by the state’s department of health. In Colorado, the board of medical examiners recommended EPT in response to the compelling need for partners to receive treatment.33 Nevada’s regulations adopt the CDC’s latest STD treatment guidelines, which include EPT.34 Lacking any contrary statutory or regulatory provisions, we deemed that EPT was permissible in these jurisdictions. In Washington State, the state pharmacy board noted the distinction in state law between prescribing medications and delivering them; although only licensed health practitioners may prescribe drugs, STD patients or nonlicensed public health workers may deliver them, thus facilitating EPT.

Expedited Partner Therapy Is Probably Legally Prohibited

Our interpretation of the laws has led us to conclude that in 13 jurisdictions, the practice of EPT by clinicians or others is probably precluded. In Arkansas,

[a] physician exhibits gross negligence if he provides . . . any form of treatment, including prescribing legend drugs, without first establishing a proper physician/patient relationship.35

Louisiana state law requires that a prescription may only be issued pursuant to a valid physician–patient relationship and physical examination.36 Oklahoma similarly prohibits a physician from prescribing a drug “without sufficient [medical] examination and the establishment of a valid hysician-patient relationship.”37 In each of these examples, a physician–patient relationship or physical examination is a statutory precursor to distribution of prescription medications. Absent alternative legal authority for EPT, its practice is effectively prohibited.

Expedited Partner Therapy Is Legally Potentially Allowable

EPT is legally potentially allowable in 28 jurisdictions, because the laws within these jurisdictions may allow EPT, subject to specific interpretations of inconsistent or ambiguous provisions, policy statements supporting EPT, or regulations adopting current STD treatment guidelines that support EPT. Because the permissibility or prohibition of EPT in these jurisdictions was unclear, we looked to authorities that indicated support for EPT or a path to its legality.38 For example, statutes in several jurisdictions (Indiana, Maine, Montana, Nebraska, North Carolina, South Carolina, Wisconsin) adopted the CDC’s STD treatment guidelines,4 which may effectively endorse EPT unless trumped by a contrary statutory provision. State public health authorities in Minnesota and Utah may allow specific or “standing order” protocols for treating nonpatients for certain conditions such as STDs, which may facilitate the practice of EPT.39,40

DISCUSSION

Our assessment suggests that over 75% of the 53 jurisdictions we studied feature laws that either explicitly permit or potentially allow EPT, a finding that runs counter to those of Golden et al.13 in 2005. Through their survey of representatives of state boards of medicine and pharmacy, they concluded that most boards (88%) perceived EPT as illegal or of “uncertain legality.” There are at least 3 principal reasons for these conflicting findings: (1) Golden et al.’s study was limited to a cohort of medical and pharmaceutical board members; (2) most (if not all) of the participants in the study by Golden et al. were not legally trained, were lacking in specific knowledge of legal issues, or were not required to seek legal information within their jurisdictions to facilitate their responses; and (3) as Golden et al. acknowledge, there was simply no prior, significant legal research on the lawfulness of EPT to providing guidance to their participants.13 In essence, their respondents’ views seemed to be based more on perceived illegalities, not actual ones.

Although our analysis suggests a favorable outlook for EPT, the existing legal landscape concerning EPT is ambiguous in a number of states. In most jurisdictions, there is an absence of specific law to authorize, endorse, or support EPT. In some jurisdictions, laws seem to contradict one another. Public health authorities, health care professionals, and policy-makers in these jurisdictions must weigh existing law and policy options and be prepared to seek legal reforms where necessary. Changes in legally binding authorities (e.g., statutes, regulations) and the influence of nonbinding legal sources (e.g., medical and pharmacy board policies, attorney general opinions, insurer policies) may alter the legal environment. Accordingly, we propose a series of recommendations to facilitate the practice of EPT to protect the interests of clinicians, patients, and their sexual partners.

Laws Expressly Endorsing Expedited Partner Therapy

Laws that expressly endorse EPT should be enacted. Statutory or other laws that explicitly allow EPT empower physicians and others to practice without fear of sanction, liability, or other harms. Effective legislation or regulation can also help implementation of EPT by broadening the range of diseases that apply to EPT, identifying health care practitioners who may prescribe medications, and expressly authorizing its use amid potential contradictory laws or policies. To date, only 4 states (California, Maryland, Minnesota, and Tennessee) have enacted laws that expressly endorse or support EPT. Legislative activity, however, is ongoing. In May 2006, a bill was introduced in New York that would have authorized health care practitioners to use EPT for chlamydial infection, but it passed only 1 house before the legislative session ended.41 Additional bills have been introduced in Wisconsin42 and Massachusetts,43 but they failed to pass. Specific statutory enactments may be required to practice EPT in states such as Arizona44 and Louisiana45 where current statutory language precludes EPT.

Exceptions to Existing Prescription Requirements

Exceptions to existing prescription requirements should be created. Prescription requirements can challenge the implementation of EPT by requiring patient identifying information on prescription labels, or by prohibiting the dispensing of drugs to individuals whom the physician has not examined. Thirty-eight jurisdictions require that prescription labels contain identifying information (e.g., name, address), which may require that the person for whom the medication is intended be identified on the label prior to dispensation. Although not consistently problematic, this requirement may impede EPT because a patient may not know or may be reluctant to share the required information for his or her partner. Regulatory exceptions to prescription label requirements may facilitate EPT by allowing clinicians to provide “blank” prescriptions or an “extra dose” for the patient to deliver to the partner.

Thirteen jurisdictions do not allow pharmacists to dispense medications to individuals who have not undergone a physical examination, have failed to establish a physician–patient relationship, or are not the ultimate user of a prescription. These laws may limit the ability of patients or partners to fill prescriptions written for the partner, if the pharmacist is aware that the partner has not been examined or is not a patient of the prescribing clinician. Although helping to protect the public, these prescription requirements should be slightly amended to reflect the greater public health benefits stemming from EPT.

Professional Endorsements

Endorsements from professional boards and associations should be sought. Most jurisdictions’ laws do not stipulate that issuing a prescription without prior medical evaluation or outside the physician–patient relationship is a per se instance of physician misconduct, deferring instead to the discretion of medical, nursing, or pharmaceutical licensing authorities or boards at local, state, or national levels. Some state medical boards expressly endorse EPT. On a national level, the American Medical Association has recently endorsed the practice of EPT as applied to chlamydial infection and gonorrhea.46,47 Additional opinions of professional boards or associations consistent with that of the American Medical Association could help resolve legal uncertainties concerning its practice in states whose laws are silent about EPT, such as Georgia29 and Oregon,29 or states with inconsistent authorities regarding EPT, such as North Carolina14,48 or Missouri.49

Insurance Reimbursements for Patients and Partners

Insurance reimbursements for STD treatments for patients and partners should be supported. Economic factors have the potential to affect the practice of EPT as well. For example, who pays for the extra dose of antibiotics distributed to the patient for the partner? Should a patient’s health insurance provider cover the costs of 2 doses, even though the partner (who may or may not be insured by the same provider) is the recipient of the extra dose? Denying payment for these medications is antithetical to health promotion because treating the partner of a patient with an STD can be directly tied to improving the health of the patient. Although costs for antibiotics to treat STDs are low (prices vary, depending on the form of medication11,12), health insurance providers may still seek to deny payment to the patient for the partner’s “half.” California’s Medi-Cal program (which administers Medicaid benefits) does not allow a patient’s account to pay for a partner’s treatment through EPT, even though EPT is explicitly authorized by state law. Although this economic issue does not arise when a partner receives a separate prescription in his or her name, prescription drug laws (as noted in “Background”) may curtail this practice. Laws should permit health insurers’ payment of the patient’s minimal expenses (i.e., the extra cost of the partner’s drugs) in delivering medications to partners through EPT, but not any additional health care needs of the partner.

CONCLUSIONS

Significant morbidity from STDs in the United States, coupled with diminished resources for traditional partner management practices, requires new public health strategies. By combining patient-based partner notification with clinical treatment through standard prescription antibiotics, EPT offers a promising new tool to improve treatment for some STDs, but its practice may be limited by perceived legal impediments. Our research, however, suggests that laws in most jurisdictions either expressly permit EPT or do not categorically prohibit it. Interpretation of existing laws or additional changes to laws may facilitate the implementation of EPT in many jurisdictions by resolving contradictory licensing, public health, or prescription laws. In turn, EPT may increasingly become an option for treating partners of STD patients and preventing transmission or reinfection from some STDs.

Acknowledgments

The Center for Law and the Public’s Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health is supported through Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Cooperative agreement (U50/CCU323385–02).

We gratefully acknowledge the intellectual contributions of Elizabeth Meltzer, JD, MPH candidate, George-town and Johns Hopkins Universities; Jennifer Gray, JD, MPH, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; and Karen Mckie, JD, MLS, Stuart Berman, MD, ScM, Susan Bradley, Jill Wasserman, MPH, and Rachel Wynn, MPH, of the CDC.

Note. The contents of this essay are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors J. G. Hodge Jr and A. Pulver cosupervised the study and participated in the conceptualization and design of the study, acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of data. D. Bhattacharya and E. F. Brown participated in the conceptualization and design of the study, acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of data. All authors contributed to the drafting of the essay and its critical revision for important intellectual content.

References

- 1.Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W Jr. STD among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36(1): 6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fact sheet—gonorrhea. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/Gonorrhea/default.htm. Accessed January 22, 2007.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fact sheet—chlamydial infection. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/Chlamydia/STDFact-Chlamydia. Accessed January 22, 2007.

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006; 55(RR-11):5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parran T. Shadow on the Land: Syphilis. New York, NY: Reynal and Hitchcock; 1937.

- 6.Hodge JG, Gostin LO. Handling cases of wilful exposure through HIV partner counseling and referral services. Rutgers Women’s Rights Law Reporter. 2001;22:45–62. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Program Operations Guidance: Partner Services. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2000.

- 8.HIV Partner Services and Referral Services: Guidance. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1998.

- 9.Golden MR, Hogben M, Handsfield HH, et al. Partner notification for HIV and STD in the United States: low coverage for gonorrhea, chlamydial infection and HIV. Sex Transm Dis. 2003; 30:490–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Expedited partner therapy in the management of sexually transmitted diseases. 2006. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/ept. Accessed January 29, 2007.

- 11.2003 Drug Topics Red Book. Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics Co Inc; 2003.

- 12.Zithromax, cefixime, cefpodoxime, ciprofloxacin. In: PDR Electronic Library [online database]. Greenwood Village, Colo: Thomson Micromedex. Updated periodically.

- 13.Golden MR, Anukam U, Williams DH, et al. The legal status of patient-delivered partner therapy for sexually transmitted infections in the United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32: 112–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.North Carolina Medical Board position statement: contact with patients before prescribing. Available at: http://www.ncmedboard.org. Accessed January 22, 2007.

- 15.Maryland Board of Physician Quality Assurance. Internet prescribing: does it meet the standard of care? BPQR Newsl. 1999;7(1):1. Available at: http://dhmh.state.md.us/pharmacyboard/acrobat/BPQAnewsletter.pdf. Accessed January 22, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arno PS, Levine C, Memmott MM. The economic value of informal caregiving. Health Aff. 1999;18(2):182–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Medical Association. Health risks: issues and risks in caregiving. Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/8802.html. Accessed January 22, 2007.

- 18.Bishop T. Pupils to get free Flumist: state will dispense 250,000 doses of MedImmune vaccine. Baltimore Sun. September 14, 2006:1D.

- 19.Harris G. FDA approves broader access to next-day pill. New York Times. August 25, 2006:A1. [PubMed]

- 20.Colo Rev Stat §12–22–123(2).

- 21.Niccolai LM, Winston DM. Physicians’ opinions on partner management for nonviral sexually transmitted infections. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28: 229–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fla Stat §465.023.

- 23.Mich Comp Laws Ann §333.17751.

- 24.WVa Code §30–5–3.

- 25.Md Code Ann Health-Occ §12–102.

- 26.Mich Comp Laws Ann §333.17745.

- 27.Fla Stat Ann §384.27.

- 28.Controlled Substances Act, 21 USC §801 et seq. (1970).

- 29.Hodge JG, Brown EF, Bhattacharya D. Assessing legal and policy issues concerning expedited partner therapies for sexually transmitted diseases. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/ept/legal/default.htm. Accessed January 22, 2007.

- 30.Heymann DL, ed. Control Of Communicable Diseases Manual. 18th ed. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2004.

- 31.Cal Health & Safety Code §120582.

- 32.Rule 0880–2.14(9)(a)-(d) of the Tenn State Board of Medical Examiners.

- 33.Colorado Medical Board of Examiners. Policy number: 40–10: appropriateness of treating partners of patients with sexually transmitted infections. Available at: http://www.dora.state.co.us/medical/policies/40-10.pdf. Accessed January 22, 2007.

- 34.Nev Admin Code §441A.200.

- 35.Ark Code State Medical Board Regulation No. 2(8).

- 36.La Admin Code Tit 46 Part LIII Chapt 25 Subchapt A §2515.

- 37.Okla Stat Tit 59 §§509(12), 637.

- 38.NM Admin Code 16.10.8.8 (L)(2).

- 39.Minn Stat Ann §§148.235, 151.37.

- 40.Utah Code Ann § 58–17b–620.

- 41.NY State Assembly Bill A11441.

- 42.Wisc Assembly Bill 995, 96th Sess (2004).

- 43.Mass Senate Bill 650, 183rd Sess (2003).

- 44.Ariz Rev Stat Ann §32–1401 (27) (ss) (2005).

- 45.La Admin Code Tit 46 Part LIII Chapt 25 Subchapt A §2515 (2004).

- 46.American Medical Association. D-440.968 expedited partner therapy. Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/apps/pf_new/pf_online?f_n=browse&doc=policyfiles/DIR/D-440.968.HTM. Accessed January 22, 2007.

- 47.Council on Science and Public Health. Report 7 (A-06). Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/16410.html. Accessed January 22, 2007.

- 48.10A NC Admin Code 41A. 0201.

- 49.Mo Code Regs Ann Tit 19, §20–20.040.