Abstract

Objectives. We examined whether state tobacco control programs are effective in reducing the prevalence of adult smoking.

Methods. We used state survey data on smoking from 1985 to 2003 in a quasi-experimental design to examine the association between cumulative state antitobacco program expenditures and changes in adult smoking prevalence, after we controlled for confounding.

Results. From 1985 to 2003, national adult smoking prevalence declined from 29.5% to 18.6% (P<.001). Increases in state per capita tobacco control program expenditures were independently associated with declines in prevalence. Program expenditures were more effective in reducing smoking prevalence among adults aged 25 or older than for adults aged 18 to 24 years, whereas cigarette prices had a stronger effect on adults aged 18 to 24 years. If, starting in 1995, all states had funded their tobacco control programs at the minimum or optimal levels recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there would have been 2.2 million to 7.1 million fewer smokers by 2003.

Conclusions. State tobacco control program expenditures are independently associated with overall reductions in adult smoking prevalence.

Recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) showed that adult smoking remained constant at 20.8% from 2004 to 2005 after years of steady decline.1 The CDC study cited a 27% decline in funding for tobacco control programs from 2002 through 2006 and smaller annual increases in cigarette prices in recent years as 2 possible explanations for stalled smoking rates. Our study is a systematic assessment of the association between adult smoking, funding for state tobacco control programs, and state cigarette excise taxes.

In 1989, California began the first comprehensive statewide tobacco control program in the United States after passage of a state ballot measure that raised cigarette excise taxes by $0.25.2 Comprehensive programs include interventions such as mass media campaigns, increased cigarette excise taxes, telephone quit lines, reduced out-of-pocket costs for smoking cessation treatment, health care provider assistance for cessation, and restrictions on secondhand smoke in public places.3–6 Subsequently, other states, including Massachusetts in 1992, Arizona in 1995, and Florida in 1998, began similar large-scale state tobacco control programs.3 Multistate tobacco control interventions with substantial financial support began in the 1990s, with assistance from US government programs (e.g., the CDC’s Initiatives to Mobilize for the Prevention and Control of Tobacco Use [IMPACT] and the National Cancer Institute’s Americans Stop Smoking Intervention Study [ASSIST]) and other national programs.3

Some states also committed resources from other sources, such as revenue from the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) between the 4 largest tobacco companies in the United States and 46 US states.7 The MSA imposes restrictions on the advertising, promotion, and marketing or packaging of cigarettes, including a ban on tobacco advertising that targets people younger than 18, and requires the tobacco companies to pay $246 billion over 25 years to the states. The MSA also established a foundation that became the American Legacy Foundation.

Extensive research has shown that state tobacco control programs, combined with other efforts, such as the American Legacy Foundation’s national truth campaign, have been effective in reducing adolescent tobacco use.3,8,9 Following a large increase in adolescent smoking during the mid-1990s, there has been an unprecedented decline, with the national prevalence among high school students dropping from 36.4% in 1997 to 21.9% in 2003.10

In marked contrast, there has been little research into the effects of state programs on the prevalence of adult smoking, which is unfortunate given that smoking cessation confers substantial health benefits to adults.3,11,12 To date, findings from California, Massachusetts, and Arizona suggest that state tobacco control programs have had some effect on adults.13–16 From 1988 through 1999, the prevalence of adult smoking in California declined from 22.8% to 17.1%, compared with an overall national decline from 28.1% to 23.5% (a relative percentage decline of 25% in California and 16% elsewhere).13,14 From 1992 through 1999, the relative percentage decline in adult smoking was 8% in Massachusetts compared with 6% nationwide.14,15 Findings from Arizona from 1996 to 1999 suggest a greater effect: the relative percentage decline was 21% compared with 8% nationwide.16 In addition, per capita cigarette sales—a proxy for cigarette consumption—have declined faster in Arizona, California, Massachusetts, and Oregon (where another large-scale program began in 1997) than in the rest of the United States since the programs’ implementation.17 The ASSIST evaluation showed that smoking prevalence decreased more in ASSIST states than in non-ASSIST states by the end of an 8-year intervention; by contrast, the evaluation found no difference in per capita cigarette consumption.6,18

These few state-specific studies on the prevalence of adult smoking had important limitations. First, state-specific findings may not be generalizable. Second, none of the studies considered the key role of cigarette price increases on prevalence (i.e., through higher cigarette excise taxes, which have consistently been shown to reduce cigarette consumption and prevalence)3 or controlled for other state characteristics, such as demographic changes or secular trends. Third, the studies did not assess the potential effects of programs on adults of different ages. Although the ASSIST evaluation provides a more comprehensive view of state tobacco control programs, it failed to control for baseline differences in state-level demographics and policy variables between ASSIST and non-ASSIST states. Finally, none of the studies considered the possible long-term effects of tobacco control programs on adult smoking.

In 1999, the CDC published Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs,19 which provided states with guidelines and recommendations for 9 tobacco control program activities (e.g., community programs, counter-marketing, cessation), along with minimum and optimum funding levels for each specific activity. On the basis of this document, in fiscal year 2006, states should have allocated $6.47 per capita minimum and $17.14 optimally to tobacco control programs (i.e., the $5.98 and $15.85, respectively, recommended in the 1999 CDC document, adjusted for inflation).

We used data on state tobacco control program expenditures and periodic surveys of adult smoking prevalence conducted by the US Census Bureau from 1985 to 2003 to answer the following questions: (1) After control for potentially confounding factors (e.g., cigarette excise taxes), were increases in state tobacco control program expenditures independently associated with declines in adult smoking prevalence, and did effects differ by age group? (2) What would have been the predicted effect of state tobacco control program expenditures on adult smoking prevalence if all states had met CDC-recommended minimum or optimum per capita funding levels from 1995 to 2003?

METHODS

Adult Smoking Prevalence Data

Information on current smoking prevalence for adults was obtained from supplements to the Census Bureau’s Current Population Surveys in 1985, 1989, 1992–1993, 1995–1996, 1998–1999, 2000, 2001–2002, and 2003 (combined years indicate periods when data collection crossed calendar years). Briefly, Current Population Surveys are monthly surveys of approximately 50000 households, in which persons 15 years or older are interviewed about labor force characteristics (e.g., employment status, earnings) and other measures. Supplements to these surveys that contained questions about tobacco use (Tobacco Use Supplements) were included during certain months and years. A mixed data collection mode was used, with approximately 34% of data collected through in-person interviews and 66% through telephone interviews20; some proxy responses were allowed. (Details about current population surveys are provided elsewhere.20) Between 1995 and 2003, response rates for the Tobacco Use Supplements ranged from 71.6% to 88%.21–25 Sample sizes for the Tobacco Use Supplements ranged from 119277 to 151237. Analyses were limited to adults 18 or older who responded themselves.

In 1985 and 1989, current smoking was defined as having smoked 100 cigarettes in a lifetime and smoking now. In subsequent years, and consistent with other national and state surveys that obtain data on smoking,26,27 current smoking was defined as smoking 100 cigarettes in a lifetime and now smoking every day or some days. (This slightly different definition results in prevalence estimates that are about 1 percentage point higher.28) In addition to smoking status, data on demographics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, education level, income level, and employment status) and interview mode (in-person or telephone) were obtained.

State Tobacco Control Program Expenditure Data

Data on annual state expenditures for tobacco control programs from fiscal years 1985 to 2004, which came from a variety of state and national sources, are described in more detail elsewhere.17 Before the MSA, most funds for other state programs came from national programs (approximately 75%); after the MSA, most came from state resources (approximately 87%).

Tobacco control programs encompass a variety of activities and interventions. States had much leeway in how they implemented their programs. For example, Florida and Mississippi specifically targeted their efforts toward youths.3 Unfortunately, because most state tobacco control programs did not include expenditure data by types of activities, it was not possible to assess the potential effect of specific tobacco control activities, or mix of activities, on adult smoking.

Because program expenditures are a function of state population size, expenditure data were normalized. Total funding amounts were divided by annual state population estimates to create a per capita measure of tobacco control expenditures.

Cigarette Price Data

Data on state cigarette prices from fiscal years 1985 to 2004 were obtained from annual volumes of The Tax Burden on Tobacco.29 For each state and year, the cigarette price was considered to be the weighted average price per pack as of November 1 of the state’s fiscal year (e.g., the cigarette price for year 2000 is the weighted average price per pack as of November 1, 1999). We interpolated monthly cigarette prices on the basis of the weighted average price per pack, allowing us to match the appropriate state cigarette price to the survey respondent’s interview date.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive analyses.

All analyses used sampling weights and were conducted using Stata version 9.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Tex). Overall and age-specific (18–24, 25–39, and ≥40 years) national prevalence estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were produced for each Current Population Survey wave. These age categories were chosen because previous studies found that young adult smokers were more responsive than were older smokers to cigarette price changes.30,31

Multivariate analyses.

Because there was a large variation in the dates when states began their tobacco control programs and in their expenditures, we used a quasi-experimental design (i.e., states were not randomly assigned to treatment conditions) to examine the relationship between the growth in state expenditures and changes in state adult smoking prevalence. To assess whether there was an independent relationship between state expenditures and adult smoking prevalence, we created logit multivariate regression models using a person’s current smoking status as the dependent variable and cumulative tobacco control program expenditure levels as the main independent variable.

We used cumulative expenditures for 2 reasons. First, some types of expenditures in any given year (e.g., training, community mobilization to effect policy change) are unlikely to affect adult use immediately but could affect use over a longer period.3,6 Second, even expenditures for specific programs and services (e.g., media interventions, quit lines) may affect adult prevalence rates several years later, because successful cessation is a process that usually takes many years and multiple quit attempts and cohorts of youths with decreased initiation rates will slowly enter the adult population.3,4,32 Both of these concepts imply that investments in any one year may have lasting effects on smoking behavior in future years. Thus, a cumulative measure of tobacco control program expenditures was created that equaled current annual expenditures plus past expenditures, discounted by 25% per year (i.e., expenditures for the past year were counted as 75% of the actual total, total expenditures for 2 years earlier were deducted by a further 25%, etc.). Except for a report by Farrelly et al.,17 who used a 5% annual discount rate in an analysis that examined the correlation between cumulative state tobacco control programs and state per capita tobacco control expenditures, there was little guidance on what would be an appropriate discount rate. As a result, we also report results using a 10% and a 50% discount rate.

To assess whether there were independent effects from cumulative program expenditures, we added several other variables to the model, including cigarette price adjusted for inflation, individual sociodemographic characteristics, interview mode, and indicator variables for each year (to account for secular trends). Because of the strong possibility that actual state smoking prevalence at the time states began their programs would be correlated with program funding decisions (e.g., tobacco-producing states are less likely to invest in tobacco control activities and more likely to have high smoking prevalence),28 we also included indicator variables for each state to control for such preexisting differences (i.e., state fixed effects). This design allowed us to relate changes in state smoking prevalence to changes in tobacco control expenditures, rather than simply correlating prevalence with level of expenditures. Indicator variables were also included to account for state programs that focused primarily on youths, because such program expenditures may have a differential effect on adult prevalence.

Unstandardized parameter estimates from the models represented the marginal change in smoking prevalence because of incremental changes in the independent variables. We assessed statistical significance using P values. In the “Results” section, we present parameter estimates for the effects of cumulative state tobacco control program expenditures and average cigarette prices on smoking prevalence; estimates for the remaining variables in the models are available upon request from M. C. F. In addition, to aid the interpretation of effect sizes, we report elasticities that show the percentage change in the outcome for a given percentage change in the independent variable. For example, a cigarette price elasticity of −0.3 indicates that a 10% increase in price would lead to a 3% drop in smoking. With a discrete tobacco control intervention (i.e., intervention vs control), one can illustrate the effect of the intervention using an odds ratio. In this case, the intervention is represented by a continuous measure (or dose).

Because our results suggested that cumulative state tobacco control expenditures were independently correlated with declines in adult smoking prevalence, we estimated the predicted change in smoking prevalence for a given change in tobacco control investments under 2 “what if” scenarios. Because most states do not fund tobacco control programs at the minimum levels recommended by the CDC,33 we first estimated what the national adult smoking prevalence would be if all states had funded their tobacco control programs at the CDC-recommended minimum funding levels every year from fiscal years 1995 to 2004 (constant at $6.47 per person annually in 2006 inflation-adjusted dollars).19 The same approach was then used to estimate national adult smoking prevalence if all states had funded such programs at the CDC-recommended optimum level (an average of $17.14 per person annually in 2006 inflation-adjusted dollars).19

RESULTS

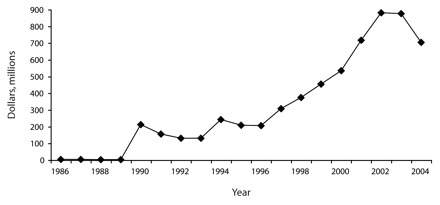

From 1985 to 2003, overall national adult smoking prevalence declined more than one third, from 29.5% to 18.6% (Table 1 ▶). Smoking prevalence significantly declined among adults in all age groups. Overall cumulative expenditures on state tobacco control programs, which were minimal before the initiation of California’s program in 1989, declined slightly during the early 1990s but increased sharply from 1996 to 2002 (Figure 1 ▶).

TABLE 1—

Overall and Age-Specific Adult Smoking Prevalence: United States, Current Population Survey, 1985–2003

| Year | Overall, % (95% CI) | 18–24 y, % (95% CI) | 25–39 y, % (95% CI) | ≥40 y, % (95% CI) |

| 1985 | 29.5 (29.1, 29.9) | 33.7 (32.4, 35.1) | 32.9 (32.2, 33.6) | 26.3 (25.8, 26.9) |

| 1989 | 26.3 (25.9, 26.7) | 25.8 (24.6, 26.9) | 30.0 (29.4, 30.7) | 24.0 (23.5, 24.4) |

| 1992/93 | 24.3 (24.1, 24.5) | 25.7 (25.1, 26.4) | 28.7 (28.3, 29.1) | 21.3 (21.1, 21.6) |

| 1995/96 | 23.4 (24.1, 24.5) | 25.8 (25.1, 26.6) | 27.2 (26.8, 27.6) | 20.8 (20.5, 21.0) |

| 1998/99 | 21.7 (21.5, 22.0) | 26.0 (25.2, 26.8) | 25.0 (24.6, 25.4) | 19.3 (19.0, 19.6) |

| 2000 | 21.5 (21.3, 21.8) | 26.4 (25.5, 27.3) | 24.7 (24.2, 25.1) | 19.1 (18.8, 19.4) |

| 2001/02 | 20.7 (20.5, 20.9) | 26.0 (25.2, 26.8) | 23.4 (23.0, 23.9) | 18.5 (18.3, 18.8) |

| 2003 | 18.6 (18.4, 18.8) | 22.8 (22.1, 23.5) | 20.6 (20.2, 21.0) | 17.0 (16.7, 17.2) |

Note. CI = confidence interval.

FIGURE 1—

Total expenditures on tobacco control programs: United States, fiscal years 1986 to 2004.

Note. Expenditures are in 2006 inflation-adjusted dollars.

Results from the regression models (Table 2 ▶) demonstrate that increases in state tobacco control program expenditures were independently associated with reductions in adult smoking prevalence (P<.01) regardless of the level of discounting of past tobacco control expenditures. The elasticities imply that doubling expenditures would likely lead to a 1.0% to 1.7% decrease in smoking prevalence, with the larger effects associated with smaller discount rates. The fact that smaller discount rates give greater weight to past expenditures suggests that past expenditures are programmatically relevant.

TABLE 2—

Parameter Estimates and Elasticities for the Independent Effect of Cumulative Per Capita State Tobacco Control Program Expenditures and Cigarette Prices on Adult Smoking Prevalence, by Age Groupa and Annual Percentage Discount Rate for Tobacco Control Expenditures: United States, Current Population Survey, 1985–2003

| 10% Discount | 25% Discount | 50% Discount | ||||

| b (P ) | Elasticity | b (P ) | Elasticity | b (P ) | Elasticity | |

| Overall population | ||||||

| Cumulative per capita expenditures | −0.040 (<.01) | −0.017 | −0.048 (<.01) | −0.014 | −0.052 (<.01) | −0.010 |

| Real cigarette price | −0.025 (.05) | −0.059 | −0.033 (.01) | −0.076 | −0.042 (.01) | −0.097 |

| Aged 18–24 years | ||||||

| Cumulative per capita expenditures | −0.035 (.04) | −0.014 | −0.031 (.21) | −0.009 | −0.016 (.66) | −0.003 |

| Real cigarette price | −0.123 (<.01) | −0.270 | −0.136 (<.01) | −0.297 | −0.147 (<.01) | −0.322 |

| Aged 25–39 years | ||||||

| Cumulative per capita expenditures | −0.049 (<.01) | −0.019 | −0.053 (<.01) | −0.015 | −0.050 (<.01) | −0.09 |

| Real cigarette price | 0.030 (.20) | 0.065 | 0.017 (.431) | 0.050 | 0.006 (.78) | 0.013 |

| Aged ≥40 years | ||||||

| Cumulative per capita expenditures | −0.038 (<.01) | −0.017 | −0.050 (<.01) | −0.016 | −0.063 (<.01) | −0.013 |

| Real cigarette price | −0.035 (.04) | −0.083 | −0.039 (.02) | −0.094 | −0.046 (.01) | −0.111 |

Note. Parameter estimates were controlled for the effects of age, age squared, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, education level, employment status, income level, missing demographic values, interview mode (in person vs telephone), youth-oriented tobacco control program, the interaction between youth-oriented antitobacco program and funding, state of residence, and year of survey participation. For explanation of percentage discount and elasticity, see “Methods” section.

aFor each age group, the number of people responding to the survey who provided complete information on all of the variables used in the analysis was as follows: overall population = 1 210 280; 18 to 24 years = 112 906; 25 to 39 years = 373 556; 40 and older = 723 818.

Increases in cigarette prices were also independently associated with decreases in overall adult smoking prevalence, with larger effects in models with a greater discounting of expenditures. A doubling of prices would likely lead to a 5.9% to 9.7% relative percentage decline in smoking. There were differences by age group as well: higher state tobacco control program expenditures were significantly and consistently associated with declines in smoking prevalence among adults aged 25 to 39 years and among those 40 years or older, but among adults aged 18 to 24 years, an association was found only in the model with cumulative expenditures discounted at 10%. By contrast, higher cigarette prices were significantly associated with lower prevalence among adults aged 18 to 24 years and those 40 years or older, but not among adults aged 25 to 39 years.

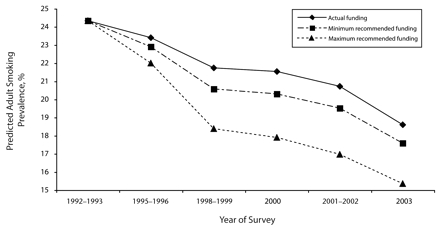

Figure 2 ▶ illustrates the estimated magnitude of the effect of cumulative state tobacco control program expenditures (using the 25% discount for expenditures) if all states had invested at CDC-recommended minimum ($9.19) or optimum ($22.18) levels from 1995 to 2003. Predicted adult smoking prevalence in 2003 would have been lower at the minimum level (17.6% vs the actual value of 18.6%) and at the optimum level (15.4%). These represent relative declines in prevalence of 5.4% and 17.4%, respectively, and translate into an estimated 2.2 million to 7.1 million fewer adult smokers in the United States. If a 10% or 50% discount for expenditures is used, the corresponding ranges of effects would be 3.2 million to 9.8 million and 1.4 million to 4.6 million fewer smokers, respectively.

FIGURE 2—

The estimated effect that funding levels for tobacco control programs recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would have had on smoking prevalence: United States, 1992–2003.

Note. For these estimations, an annual 25% discount rate for expenditures on tobacco control programs was used. Source. RTI International State Tobacco Control Program Expenditure Database.

DISCUSSION

Using a modeling approach to control for potentially confounding factors, we demonstrated that increases in cumulative state tobacco control expenditures were independently associated with declines in adult smoking prevalence in the United States. Previous findings that increases in cigarette prices are associated with declines in adult prevalence were also confirmed.3 State tobacco control program expenditures, however, had an effect that was independent of increased cigarette prices. This effect was not uniform across all age groups: programs were consistently associated with declines in smoking for adults 25 years and older, whereas increased prices had a greater impact on adults aged 18 to 24 years. We estimate that the total number of adult smokers would have been substantially reduced if all states had funded their programs at the CDC-recommended minimum per capita levels, let alone at the optimum levels, beginning in 1995.19

Interpreting the Findings

The cumulative effect of program expenditures suggests that it requires time to convert financial resources into the capacity necessary to have an impact on effective programs and policies, and that programs and policies may need to be sustained over years for adult smokers to quit permanently.3,4,6 The greater weight we give to past expenditures, the larger the association with declines in smoking. This finding is consistent with the importance of building capacity and competence in delivering public health programs.6 This research supports the conclusion of the 2000 surgeon general’s report that comprehensive state tobacco control programs are effective,3 and it complements recent studies demonstrating that tobacco control program expenditures are associated with declines in smoking prevalence among youths8 and per capita cigarette sales.17

These results are probably conservative, for several reasons. The effect of increased program funding was assumed to be independent of the effect of cigarette price increases, which are strongly influenced by state cigarette excise tax levels.3 However, one of the major policy interventions of tobacco control programs is to support increased excise taxes.3 State tobacco control programs may create an environment in which raising excise taxes is possible, thus creating some synergy. Our analyses relied on the relatively crude measure of tobacco program activities based on state-level expenditures, and to the extent that expenditures are measured with error, the effects will be biased toward a null effect. Additionally, the efficiency by which resources are used to establish tobacco control capacity and implement effective program elements can vary for multiple reasons.6

From our data, we cannot determine the reason cumulative expenditures for state tobacco control programs reduced adult smoking, nor can we ascertain why tobacco control programs and increased cigarette prices had effects that varied by age group. More research is needed to determine how long tobacco control program expenditures have an effect and, specifically, how programs influence the determinants of smoking (e.g., social norms, attitudes, beliefs) prior to reducing smoking.5,6

Because of the absence of information from states on funding levels for specific tobacco control program activities, it was not possible to determine which activities, or combination of activities, were most effective. Other research, however, has provided strong evidence that certain tobacco control program activities are effective in reducing adult smoking prevalence.9 These activities include mass media campaigns, cessation services (through state telephone quit lines, health care providers, and reduced out-of-pocket costs for treatment), and strong secondhand smoke restrictions3,9; such activities were included as part of many state tobacco control programs throughout the period of this study.3,6,34,35

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. We relied on self-reported data to categorize adult smoking prevalence; studies suggest, however, that self-reports underestimate smoking status compared with biochemical validation.36–38 It is also possible that there is systematic underreporting in states with more-robust tobacco control programs, because of social desirability bias. In other words, in states where tobacco control programs have succeeded in making smoking less socially acceptable, smokers may be more likely to give the socially desirable response—that they do not currently smoke. If this is true, then our results would overestimate the true effects of tobacco control programs. In addition, we did not control for secondhand smoke laws or ordinances because these are commonly a major focus of state tobacco control programs,3,9 and some research suggests that secondhand smoke restrictions play an important role in motivating smokers to quit.39

Implications

Despite extensive research demonstrating the effectiveness of state tobacco control programs in reducing prevalence3,8,9 and improving health outcomes (e.g., reducing lung cancer and heart disease),40,41 as of 2005, only 4 states funded their programs at the minimum levels—and none at optimal levels—recommended by the CDC.33,34 In fact, many states have substantially reduced funding for their tobacco control programs. Between fiscal years 2002 and 2005 alone, overall funding for state tobacco control programs declined by 28%.34 Funding has been cut by up to 75% in some states, essentially gutting flagship programs in Florida, Massachusetts, and Oregon.

Although state leaders indicated their intention to spend a significant portion of the 1998 MSA funds on tobacco control efforts,42 in 2006 only an estimated 3% of state MSA funds were used for such purposes.34 Between 2002 and 2005, 41 states and the District of Columbia increased cigarette excise taxes,29 but few states earmark excise tax revenue to support tobacco control programs. Instead, MSA funds and increased tobacco excise taxes fill short-term budget deficits.7

Despite a strong track record of success and the fact that cigarette smoking remains the leading preventable cause of death, resulting in an estimated 400000 deaths annually in the United States,3 state tobacco control programs have not been institutionalized, and funding for them is considered discretionary by many. The findings strengthen the evidence that state tobacco control programs reduce adult smoking prevalence and have an effect that is independent of increased cigarette prices. The results also show that funding for such programs is a valuable investment. By not sufficiently funding programs at least at the CDC-recommended minimum levels, states are missing an opportunity to substantially reduce smoking-related mortality, morbidity, and economic costs.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the Office on Smoking and Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, under a project entitled the Coordinated Evaluation of Statewide Tobacco Control Programs.

We thank Susan Murchie for editorial support.

Human Participant Protection No protocol approval was needed for this secondary data analysis.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors M.C. Farrelly and T.F. Pechacek contributed to the study design, analyses, and initial and final drafts of the article. K.Y. Thomas conducted all analyses and contributed to the initial and final drafts of the article. D. Nelson contributed to the initial and final drafts of the article.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco use among adults—United States, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(42):1145–1148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bal DG, Kizer KW, Felten PG, Mozar HN, Niemeyer D. Reducing tobacco consumption in California. Development of a statewide antitobacco use campaign. JAMA. 1990;264:1570–1574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reducing Tobacco Use: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2000.

- 4.Zaza S, Briss PA, Harris KW, eds. The Guide to Community Preventive Services: What Works to Promote Health? New York, NY: Oxford Press; 2005.

- 5.Starr G, Rogers T, Schooley M, Porter S, Wiesen E, Jamison N. Key Outcome Indicators for Evaluating Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2005.

- 6.Evaluating ASSIST: A Blueprint for Understanding State-Level Tobacco Control. Bethesda, Md: National Cancer Institute; October 2006. Tobacco Control monograph 17, National Institutes of Health publication 06–6058.

- 7.Schroeder SA. Tobacco control in the wake of the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement. N Eng J Med. 2004; 350:293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tauras JA, Chaloupka FJ, Farrelly MC, et al. State tobacco control spending and youth smoking. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(2):338–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hopkins DP, Briss PA, Ricard CJ, et al. Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to reduce tobacco use and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(suppl 2):16–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.YRBSS National Youth Risk Behavior Survey: 1991–2005. Trends in the Prevalence of Cigarette Use. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2007. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/pdf/trends/2005_YRBS_Cigarette_Use.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2007.

- 11.The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2004. [PubMed]

- 12.Peto R, Darby S, Deo H, Silcocks P, Whitley E, Doll R. Smoking, smoking cessation, and lung cancer in the UK since 1950: combination of national statistics with two case–control studies. BMJ. 2000;321:323–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 1988. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1991;40(44):757–759, 765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50(40):869–873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abt Associates Inc. Independent evaluation of the Massachusetts tobacco control program: seventh annual report, January 1994 to June 2000. Report prepared for the Massachusetts Department of Health, 2000. Available at: http://www.mass.gov/Eeohhs2/docs/dph/tobacco_control/abt_7th_report.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2007.

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco use among adults—Arizona, 1996 and 1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50(20):402–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farrelly MC, Pechacek TF, Chaloupka FJ. The impact of tobacco control program expenditures on aggregate cigarette sales: 1981–2000. J Health Econ. 2003;22: 843–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stillman FA, Hartman AM, Graubard BJ, Gilpin EA, Murray DM, Gibson JT. Evaluation of the American Stop Smoking Intervention Study (ASSIST): a report of outcomes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1681–1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs—August 1999. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1999.

- 20.Current Population Survey Technical Paper 63RV: Design and Methodology. Washington, DC: Bureau of the Census; 2002. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/tp63rv.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2007.

- 21.Current Population Survey, February 2003, June 2003, and November 2003: Tobacco Use Supplement Technical Documentation. Washington, DC: Bureau of the Census; 2006.

- 22.Current Population Survey, June 2001, November 2001, and February 2002: Tobacco Use Supplement Technical Documentation. Washington, DC: Bureau of the Census; 2004.

- 23.Current Population Survey, January 2000 and May 2000: Tobacco Use Supplement Technical Documentation. Washington, DC: Bureau of the Census; 2003.

- 24.Current Population Survey, September 1998, January 1999, and May 1999: Tobacco Use Supplement Technical Documentation. Washington, DC: Bureau of the Census; 2001.

- 25.Current Population Survey, September 1995, January 1996, and May 1996: Tobacco Use Supplement Technical Documentation. Washington, DC: Bureau of the Census; 1998.

- 26.1998 National Health Interview Survey Questionnaire. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics; 2000. Available at: ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Survey_Questionnaires/NHIS/1998/qsamadlt.pdf. Accessed April 8, 2005.

- 27.Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1996–2003. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/technical_infodata/surveydata.htm. Accessed April 8, 2005.

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 1992, and changes in the definition of current cigarette smoking. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1994;43(19):342–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orzechowski and Walker Consulting Firm. The Tax Burden on Tobacco, Historical Compilation, Volume 40. Washington, DC: The Tobacco Institute; 2005.

- 30.Farrelly MC, Bray JW, Pechacek T, Woollery T. Response by adults to increases in cigarette prices by sociodemographic characteristics. South Econ J. 2001;68: 156–165. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evans WN, Farrelly MC. The compensating behavior of smokers: taxes, tar, and nicotine. RAND J Econ. 1998;29:578–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Women and Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2001. [PubMed]

- 33.Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. Show us the money: a report on the states’ allocation of the tobacco settlement dollars, 2004. Available at: http://tobaccofreekids.org/reports/settlements. Accessed September 2005.

- 34.A Broken Promise to Our Children: The 1998 Tobacco Settlement Seven Years Later. Washington, DC: Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids; 2005. Available at: http://www.tobaccofreekids.org/reports/settlements/2006/fullreport.pdf. Accessed August 2006.

- 35.Mueller NB, Luke DA, Herbers SH, Montgomery TP. The best practices: use of the guidelines by ten state tobacco control programs. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31: 300–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benowitz NL, Jacob P 3rd, Ahijevych K, et al. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4:149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bauman KE, Koch GG. Validity of self-reports and descriptive and analytical conclusions: the case of cigarette smoking by adolescents and their mothers. Am J Epidemiol. 1983;118:90–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patrick DL, Cheadle A, Thompson DC, Diehr P, Koepsell T, Kinne S. The validity of self-reported smoking: a review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 1994;84: 1086–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Norman GJ, Ribisl KM, Howard-Pitney B, Howard KA, Unger JB. The relationship between home smoking bans and exposure to state tobacco control efforts and smoking behaviors. Am J Health Promot. 2000;15:81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fichtenberg CM, Glantz SA. Association of the California Tobacco Control Program with declines in cigarette consumption and mortality from heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(24):1772–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jemal A, Cokkinides VE, Shafey O, Thun MJ. Lung cancer trends in young adults: an early indicator of progress in tobacco control (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 2003;14:579–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hearings Before the US Senate Commerce Committee, 108th Cong, 1st Sess (November 12, 2003) (statement of Matthew Myers, President’s Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids).