Abstract

A community-based cluster randomized control trial in a medium-sized municipality in Tanzania was designed to increase local competence to control HIV/AIDS through actions initiated by children and adolescents aged 10 to 14 years. Representative groups from the 15 treatment communities reached mutual understanding about their objectives as health agents, prioritized their actions, and skillfully applied community drama (“skits”) to impart knowledge about the social realities and the microbiology of HIV/AIDS. In independently conducted surveys of neighborhood residents, differences were found between adults who did and did not witness the skits in their beliefs about the efficacy of children as HIV/AIDS primary change agents.

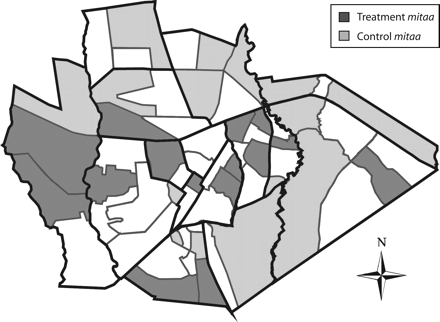

THE CHILD HEALTH AND SOCIAL Ecology (CHASE) project was initiated in 2003 to evaluate the effectiveness of children and adolescents aged 10 to 14 years (“young adolescents”) as primary change agents in a social and behavioral intervention to strengthen community approaches toward reducing the risks and stigma of HIV/AIDS. The CHASE team implemented the project in Moshi Municipality, an urbanized area of 143 000 in the Kilimanjaro region of Tanzania, which has an HIV prevalence rate of 7.3%.1 CHASE is a cluster randomized controlled trial in which neighborhood subwards, called mitaa (mtaa is the singular)—the smallest democratically elected administrative areas of the municipality—are the units of analysis (Figure 1 ▶).

FIGURE 1—

Administrative units of local government, Moshi municipality, Tanzania.

Note. Thick lines surround 15 wards and fine lines surround 61 subwards, or mitaa (60 of the 61 are residential). We matched the 30 randomized controlled mitaa on selected demographic variables and randomly assigned them to treatment and control arms in such a way that the treatment and control areas were not adjacent, unless separated by a barrier (e.g., major highways, rivers, or high walls).

The research components are standardized cross-sectional community surveys, standardized health assessments, and health promotions intervention. The community surveys asked about demographic characteristics, social perceptions, and health attitudes, with independent samples of adult residents at baseline and 1 month postintervention. The standardized health assessments were individual interviews with young adolescents and their care-givers covering health status, behavioral strengths and problems, young adolescents’ knowledge and attitudes about sexuality, parental efficacy, and HIV/AIDS at baseline and 3 months postintervention. The health promotions intervention was a fully scripted yet highly participatory curriculum for young adolescents facilitated by young adults who had recently graduated from secondary school or college to develop deliberative health promotion skills and HIV/AIDS knowledge.

We grouped 30 of the 61 mitaa in the municipality into 15 pairs matched on significant demographic variables. One mtaa per pair was randomly assigned to treatment and the other to control. The independent sample of 24 young adolescents and their caregivers were selected for participation in the trial from the 15 mtaa pairs. The control group was designated as a waiting group (the control group would eventually receive the full curriculum) and it is currently in an advanced phase of the intervention.

The intervention, known as the Young Citizens Program, is based on the integration of theories of human capability, communicative action, and social learning.2–7 The Young Citizens Program aims to develop citizenship and health promotion skills through a series of 4 progressive modules (see the box on page 204). The goal of the intervention is for the young adolescents to plan and implement integrated health promotion activities that educate their communities and encourage them to take action toward HIV/AIDS prevention, testing, and treatment.

STRUCTURE OF INTERVENTION MODULES 1–4.

Module 1 aims to promote the formation of group identity and trust among adolescents and introduce concepts of deliberation,critical thinking,assuming the perspectives of others, and preference ranking to reach mutual understanding about health issues. (5 sessions)

Module 2 educates adolescents about their potential for active citizenship by introducing their mtaa leadership and allowing them to acquire skill and confidence in observation, mapping, and interview techniques to plan and organize shared social action to build HIV/AIDS competence in their communities. (4 sessions)

Module 3 introduces adolescents to detailed biological,behavioral,and social knowledge about social transmission of disease,especially malaria and HIV/AIDS. Through deliberation and dramatization, the adolescents learn the microbiology of these highly prevalent diseases and the social circumstances leading to acquisition, diagnosis, and treatment. Adolescents receive health promotion certificates following successful learning and performing of dramatic sequences. (5 weeks)

Module 4 represents an extended period of interaction with the community, through scheduled and facilitated HIV/AIDS weekly or semiweekly performances in their mtaa. As the adolescents become increasingly skilled in presenting the social context and microbiology of HIV/AIDS in public spaces, fellow citizens engage in active public dialogue about prevention strategies, stigma reduction, and family issues. (14 sessions)

We recruited and trained Tanzanian adults (in teams of 1 university graduate and 2 secondary school graduates) to facilitate the groups. Facilitators scheduled weekly 2- to 3-hour afterschool or weekend sessions with each treatment group over a period of 28 weeks. During modules 1 through 3, the teams read, discussed, and rehearsed session scripts before holding sessions at primary school facilities. Teachers were trained to provide independent monitoring of the fidelity to scripts and relative degree of participation. In module 4, the young adolescent groups performed HIV/AIDS skits in public spaces throughout their mtaa for maximum impact. Facilitators recorded the number of community members of all ages viewing the performances.

DRAMATIZATION OF THE MICROBIOLOGY OF HIV/AIDS

Drama was selected as an innovative and interactive way for young adolescents to acquire knowledge about HIV/AIDS and openly engage community members in public performances and discussions of a complex and stigmatized topic. In Tanzania8 and elsewhere in Africa9–10 drama has been an effective participatory method for HIV/AIDS education. The community-based drama in the Young Citizens Program actively engages the community to participate in and ask questions raised by the performances.11

Module 3 is a critical transition point from building deliberative skills and research skills in the first 2 modules to understanding the corporal and social context of disease. In module 3, the young adolescents encounter the “microworld” by personifying the roles of HIV and specialized cells of the immune system interacting within the human body. In the 14 weeks of module 4, the 15 groups perform the skits in the community once or twice a week to an average of 50 citizens per session, for a total of more than 10000 person hours. They depict the microbiology to expose the community to the scientific principles behind HIV transmission, testing, and treatment. “Macroworld” skits precede and follow the microworld skits. In the macroworld skits, the young adolescents develop various real-life community scenarios that place youths at risk of infection, that encourage voluntary counseling and testing, and that expose the burdensome stigma surrounding HIV/AIDS. (See community performances at http://www.hms.harvard.edu/chase/projects/tanzania/restricted/multimedia.html.)

To assess the impact of the Young Citizens Program and its skits, a postintervention community survey conducted in the 30 trial mitaa measured attitudes and knowledge about HIV/AIDS and perception of young adolescents’ roles as community health promoters. The survey asked respondents if they had witnessed youths acting as HIV/AIDS health educators during the previous 3 months to assess the impact of witnessing the dramas regardless of the residential mtaa. We will later report on separately conducted postintervention standardized assessments that measured health and behavioral changes in the program participants and their caregivers.

DISCUSSION AND EVALUATION

As noted in Table 1 ▶, 40% of community members (17% of the control group and 57% of the treatment group) from the 30 mitaa surveyed after the intervention reported having seen groups of youths perform skits about HIV/AIDS. Those who had seen the skits were significantly more likely than those who had not to respond favorably on young adolescents’ capability as health promoters in the community. They also were more likely to agree that parents should disclose their HIV status to their children. Survey items about HIV knowledge showed no differences between those who had seen the skits and those who had not. Treatment and control mitaa overall were similar on indicators of standard of living, access to information, and civic engagement. Yet when respondents were stratified by self-reported “did not see skit” and “did see skit,” the latter group endorsed civic engagement items more often than did the former group. A multiple linear regression model of the engagement items did not significantly alter the effect size for having seen a skit.

Table 1—

Selected Items From the Posttreatment Community Survey: Moshi Municipality, Tanzania, 2006

| Item | Did Not See Skit | Saw Skit |

| Respondents (N = 1114), no. (%) | 674 (60.5) | 440 (39.5) |

| Control group (n = 490), no. (%) | 407 (83.1) | 83 (16.9) |

| Treatment group (n = 624), no. (%) | 267 (42.8) | 357 (57.2) |

| Indicators of living standards | ||

| Owns home, % | 40.9 | 39.8 |

| Water piped into home, % | 16.5 | 17.0 |

| Electricity in home, % | 57.7 | 56.6 |

| Owns a radio, % | 90.8 | 91.6 |

| Reads newspaper, % | 75.8 | 80.2 |

| Listens to radio, % | 96.6 | 96.4 |

| Regularly employed, % | 27.9 | 25.5 |

| Years lived in mtaa, mean (SD) | 10.57 (11.38) | 10.39 (10.02) |

| Indicators of civic engagement, % | ||

| Knows mtaa leader | 43.1 | 44.9 |

| Plans to move out of mtaa | 11.9 | 10.2 |

| Knows most families in mtaa | 71.6 | 80.2** |

| Very active in mtaa | 37.5 | 43.6* |

| Opinions about children and HIV/AIDS | ||

| Children can teach adults some scientific facts about HIV/AIDS,a mean (SD) | 2.77 (0.90) | 2.95 (0.88)*** |

| Children in this neighborhood can decrease discrimination against HIV-positive persons,a mean (SD) | 2.51, 0.87 | 2.88, 0.80*** |

| Children can help fight crime,a mean (SD) | 2.73, 0.87 | 3.06, 0.81*** |

| Children and adults can converse freely and openly about HIV/AIDS,a mean (SD) | 2.81, 0.85 | 2.96, 0.82*** |

| Parents should tell children about their HIV status, % | 73.8 | 78.6* |

| Efforts should be made to keep AIDS orphans in the community | 39.5 | 38.1 |

| Adult leaders should get tested for HIV,a mean (SD) | 3.27 (0.92) | 3.25 (0.95) |

| HIV Knowledge | ||

| HIV is getting worse in neighborhood,a mean (SD) | 3.20 (0.90) | 3.00 (0.97)*** |

| Leaders are not doing enough,a mean (SD) | 2.84, 1.13 | 2.83, 1.13 |

| Knows where to get tested in the neighborhood, % | 17.4 | 16.5 |

| Knows that blood test looks for antibodies, % | 17.8 | 18.3 |

| Knows that drugs cannot cure HIV, % | 98.1 | 97.0 |

a1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = agree; 4 = strongly agree.

*P < .10; **P < .05; ***P < .01.

Drama-based interventions by adults can significantly increase the use of voluntary counseling and testing services for HIV/AIDS.10 Furthermore, primary school students in East Africa have acted as health change agents, effectively imparting knowledge to their communities through participatory approaches.12 Our findings indicate that young adolescents can effectively open public channels of communication with adults and increase their sensitivity toward the impact of the HIV/AIDS pandemic on children, particularly on issues of stigma and disclosure of HIV status. Witnessing the dramas did not change adults’ information or knowledge about certain aspects of HIV/AIDS. We think the dramatic dialogue suffers from limited projection to large audiences, causing many viewers to be unable to hear the information. The length of exposure of the skits to audiences also varies. We are improving these elements in the current performances in the control mitaa.

NEXT STEPS

The young adolescents in the intervention groups are joining with facilitators in the current activities of the control groups in modules 3 and 4. Mtaa leaders of most of the 30 trial mitaa have endorsed incorporation of the Young Citizens Programs as standing committees within the democratic structure of the mitaa. To date, 7 treatment adolescent groups have mobilized their mitaa through public announcements and performances, resulting in more than 600 neighbors (aged 16–86 years) across the communities volunteering for counseling and HIV testing by counselors over the course of 3 weekends. The ultimate goal of the Young Citizens Program is to promote a range of skills and behaviors for HIV community competence in adolescents, their families, and their community members. In the context of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, children and adolescents have the most to gain in achieving HIV-competent communities by taking action to prevent their own orphanhood because of AIDS and to promote their own sexual health.

Figure 2.

A community performance in Tanzania in which young adolescents depict HIV (in the purple cape) on its knees, T4/CD4 (dressed in white with ropes around the midsection of this HIV-infected character) standing tall, and the newly arrived antiretroviral drugs (costumed in confetti). The drugs have effectively arrested replication of HIV in the T4/CD4 cell.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant RO1 MH66806). The Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center was the principal subcontractor for our Moshi-based staff and offices, and their administrative support is acknowledged.

The contributions of Child Health and Social Ecology colleagues (Abdullah Ahmed, Naomi Kimaro, Clara Massawe, John Mbando, Epifania Minja, Alice Monyo, Annastasia Mosha, John Mtesha, Rose Muro, Jonas Mwakatobe, Daniel Ngowi, Samwel Onesmo, and Juma Tety), Harvard Medical School (Maria Almond), and Harvard College (Mika Morse) and the leadership of Moshi Municipality in these community-based performances are sincerely acknowledged.

Human Participant Protection This study was approved by the Human Studies Committee at Harvard Medical School, the Ethics Review Committee at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical College, the Tanzanian Commission on Science and Technology, and the National Institute of Medical Research (Tanzania). A data safety monitoring board oversaw all phases of the study.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors N. Kamo and M. Carlson conceptualized the module 3 microbiology skits. N. Kamo is responsible for the maps (Figure 1 ▶) and photographs and the initial descriptions of module 3 sessions. M. Carlson designed protocols and schedules for training for modules 1–3 and, along with F. Earls, monitored the implementation of training for modules 1–3 and community performances. R. T. Brennan contributed to the neighborhood selection and was responsible for the data analyses and tables. F. Earls designed the structure of the randomized control trial, the community surveys and health assessments, and led the interpretation of findings and preparation of the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tanzania HIV/AIDS Indicator Survey 2003–04. Calverton, Md: Tanzania Commission for AIDS, National Bureau of Statistics, ORC Macro; 2005.

- 2.Sen A. Capability and well-being. In: Nussbaum M, Sen AK, eds. The Quality of Life. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press; 1993:30–53.

- 3.Habermas J. Reason and the Rationalization of Society. Boston, Mass: Beacon Press; 1984. The Theory of Communicative Action; vol 1.

- 4.Habermas J. Lifeworld and System: A Critique of Functionalist Reason. Boston, Mass: Beacon Press; 1987. The Theory of Communicative Action; vol 2.

- 5.Bandura A. Exercise of human agency through collective efficacy. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2000;9:75–78. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlson M, Earls F. The child as citizen: implications for the science and practice of child development. Int Soc Stud Behav Dev. 2001;38:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Earls F, Carlson M. Adolescents as collaborators: in search of well-being. In: Tienda M, Wilson WJ, eds. Youth in Cities. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2002:58–83.

- 8.Bagamoyo College of Arts, Tanzania Theatre Centre, Mabala R, Allen K. Participatory action research on HIV/AIDS through a popular theatre approach in Tanzania. Eval Program Plann. 2002;25:333–339. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harvey B, Stuart J, Swan T. Evaluation of a drama-in-education programme to increase AIDS awareness in South African high schools: a randomized community intervention trial. Int J STD AIDS. 2000;11:105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Middelkoop K, Myer L, Smit J, Wood R, Bekker LG. Design and evaluation of a drama-based intervention to promote voluntary counseling and HIV testing in a South African community. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:524–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boal A. The Theatre of the Oppressed. New York, NY: Uziden Press; 1979.

- 12.Onyango-Ouma W, Aagaard-Hansen J, Jensen B. The potential of school children as health change agents in rural western Kenya. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:1711–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]