Abstract

Objectives. We examined patterns of rapid HIV testing in a multistage national random sample of private, nonprofit, urban community clinics and community-based organizations to determine the extent of rapid HIV test availability outside the public health system.

Methods. We randomly sampled 12 primary metropolitan statistical areas in 4 regions; 746 sites were randomly sampled across areas and telephoned. Staff at 575 of the sites (78%) were reached, of which 375 were eligible and subsequently interviewed from 2005 to 2006.

Results. Seventeen percent of the sites offered rapid HIV tests (22% of clinics, 10% of community-based organizations). In multivariate models, rapid test availability was more likely among community clinics in the South (vs West), clinics in high HIV/AIDS prevalence areas, clinics with on-site laboratories and multiple locations, and clinics that performed other diagnostic tests.

Conclusions. Rapid HIV tests were provided infrequently in private, nonprofit, urban community settings. Policies that encourage greater diffusion of rapid testing are needed, especially in community-based organizations and venues with fewer resources and less access to laboratories.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) 2006 recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women encouraged routine HIV screening in all public and private health care settings, including nonprofit community health clinics that provide medical care for under-served populations.1 These recommendations supplemented 2001 CDC guidelines that recommended HIV testing of at-risk individuals in community-based organizations (CBOs; e.g., nonclinical AIDS service organizations) and outreach settings, and superseded 2001 CDC guidelines that recommended HIV testing of at-risk individuals in public and private health care settings.2 The CDC’s goal is to decrease the number of people in the United States who are unaware of their HIV status (about 25% of infected persons).3 Awareness of serostatus increases the likelihood that seropositive individuals will reduce transmission risk behaviors and allows HIV test providers to facilitate linkages to medical care.1,4,5

Although traditional HIV tests can be used for HIV screening, these tests require that clients return 1 or 2 weeks after the test to receive their results and prevention counseling. Approximately one third of clients do not return for results of traditional HIV tests across settings, with larger proportions not returning in CBOs and outreach settings.4,6 The CDC therefore recommended expansion of the use of single-session rapid HIV tests, which do not require a return visit for results.1,2 Since 2002, 6 rapid HIV tests with high sensitivity (99.3%–100%) and specificity (99.1%–100%) have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.5,7–12 As of November 2007, 4 rapid tests—OraQuick Advance (Orasure Technologies, Bethlehem, Pa), Uni-Gold Recombigen (Trinity Biotech PLC, Wicklow, Ireland), and Clearview HIV 1/2 STAT-PAK and COMPLETE HIV 1/2 (Chembio Diagnostic Systems, Medford, NY)—were waived for point-of-care use under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments and can be used by trained staff in nonclinical settings.

Rapid HIV tests have advantages over traditional HIV tests in community health settings (including community clinics and CBOs), including high posttest counseling rates, feasibility, cost-effectiveness, and client and staff acceptability.13–22 Rapid tests allow HIV-negative individuals to learn their serostatus 10 to 40 minutes posttest; reactive (“preliminary positive”) rapid test results require confirmatory testing.23 Rapid tests are ideal for community settings in which clients may not have ongoing relationships with HIV test providers and may be unlikely to return for counseling.

The scope of rapid HIV testing in US community health settings outside the public health system, including community clinics and CBOs, is unknown. Researchers have suggested that, although rapid HIV testing is feasible and cost-effective, some barriers may need to be overcome in community settings, including psychological costs to testers (e.g., anxiety resulting from a lack of sufficient preparation time for delivering peliminary positive results), counseling-related costs, and difficulties in linking seropositive individuals into care.24,25 Staff may be apprehensive about the potential for false-positive results and about learning rapid testing procedures.19 Rapid test protocols require larger blocks of time than traditional tests to perform counseling, conduct testing, document the test, and report results in 1 session.20 Regulations for HIV testing vary by state26; strict regulatory environments may make CDC recommendations difficult to implement.

We examined the scope of rapid HIV testing in the United States from 2003 to 2006 in a multistage national random sample of private, nonprofit, urban community health settings (i.e., community clinics and CBOs). We provide a baseline study of rapid HIV test availability in private community settings before the CDC’s 2006 statement on HIV screening in health care settings (including community clinics), but after the CDC’s 2001 recommendations for CBOs and community clinics.

We used the diffusion of innovation theory27 as a framework to describe the trajectory of rapid HIV testing. According to diffusion of innovation theory, innovations are likely to be adopted to the extent that they appear advantageous over existing methods; are compatible with existing infrastructure, resources, and norms; and are relatively easy to use. Organizations with greater resources and fewer barriers are more likely to adopt innovations.27 Diffusion is predicted to follow an S-shaped curve that represents the cumulative percentage of adopters divided into 5 chronological categories: rising slowly initially (innovators and early adopters), accelerating steeply until about half of the population has adopted the innovation (early majority), and leveling off as fewer non-adopters are available with whom to share the innovation (late majority and laggards).

Following the diffusion of innovation theory,27 we hypothesized that larger community clinics and CBOs would have greater resources to implement rapid HIV testing, and hence would be more likely to be offering rapid tests. We also hypothesized that community clinics and CBOs located in areas of higher AIDS prevalence, as well as areas with high concentrations of subgroups in which HIV is increasing (i.e., Black, Hispanic, and high-poverty areas) would perceive a greater need for rapid HIV testing and, thus, would be more likely to offer rapid tests. Further, we predicted that HIV test provision would differ by geographic region because of state variations in test regulations.

METHODS

Sampling Frame and Procedures

We modeled our sampling design after the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study,28,29 a national study of patients in care for HIV. We conducted multistage probability sampling by region and provider type (i.e., community clinic or CBO) to arrive at a nationally representative sample of private nonprofit community health settings in major US metropolitan areas. In the first stage, using probability sampling, we randomly selected 4 geographic locations (primary metropolitan statistical sampling areas [MSAs]) per census region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West) from a comprehensive list of 104 primary MSAs; in the second stage, we used a simple random sample to select community clinics and CBOs from a comprehensive list.

For the selection of primary MSAs, the primary MSA with the highest AIDS prevalence was chosen within each region with certainty (i.e., probability of selection for study=1.0; Los Angeles–Long Beach, Calif, New York, NY, Miami, Fla, and Chicago, Ill) and 8 other primary MSAs (Atlanta, Ga, Boston, Mass, Indianapolis, Ind, Newark, NJ, Oakland, Calif, Riverside–San Bernardino, Calif, St Louis, Mo, and Washington, DC) with probabilities of selection for study proportional to size of the number of AIDS cases in the MSA reported to the CDC as of December 2001.6 Selection of some sampling units with certainty is acceptable when the population distribution is highly skewed among sampling units, and all analyses accounted for selection with sampling weights. Within all primary MSAs in 2001, the 4 primary MSAs with the highest prevalence accounted for about one third of cumulative AIDS cases, and the total primary MSAs selected accounted for 40% of AIDS cases. Three primary MSAs were selected per region because of the need to represent all contiguous US regions while balancing cost and statistical power concerns.

Our sample conformed to the definition of a probability sample, because each site in the population had a nonzero and known probability of selection.30,31 Sampling probabilities proportionate to sample size are widely used in multistage designs with sampling units that are heterogeneous in size, such as AIDS prevalence, to prevent selection of statistically inefficient or problematic samples31 (e.g., in which few eligible respondents are present in the sampling unit). Because most data were collected from PMSAs with moderate-to-high AIDS prevalences, precision was reduced for national estimates of rapid HIV test availability but increased for estimates in areas of moderate-to-high AIDS prevalences.

Compilation of Community Clinic and Community-Based Organization List

Sample sources.

We compiled a complete list of private nonprofit community health care settings in the 12 primary MSAs from which to select a subset of sites to survey. The primary source for the sample was the National Infectious Disease Directory (NIDD), a comprehensive listing of community clinics and CBOs that are involved in infectious disease treatment and testing (including HIV). All eligible community clinics and CBOs listed in the NIDD in the selected primary MSAs were chosen for inclusion (n=626). To ensure the completeness of our list, we supplemented the NIDD list with lists of community clinics (n=427) gleaned from national Web site directories of community clinics (e.g., the Health Resources Service Administration Web site of community health centers); 73 of these sites were also included on the NIDD list.

We conducted a pilot survey of 40 community clinics and CBOs to refine exclusionary criteria, validate site contact information, and determine procedures for reaching appropriate staff for interviews. The de-duplicated list contained 980 cases (626 from the NIDD and 354 from the Web sources). Because we focused on use of rapid testing among private community clinics and CBOs outside the CDC’s purview, 31 sites receiving CDC funds for rapid HIV test demonstration projects were deleted from the list.32 We randomly sampled and telephoned 738 sites, which were approximately evenly distributed across primary MSA, region, and source list.

Eligibility criteria.

We focused on identifying private nonprofit (non–publicly funded) community providers of rapid HIV tests, of those community providers that offered any HIV testing services. We defined community nonprofit providers as those providing medical care or social services for general under-served populations. We surveyed the main branch of each organization only (but obtained information about the whole organization). Sites were eligible if they (1) were nonprofit, (2) were direct providers of medical care or social services (e.g., housing assistance, counseling, job services, food services, case management, benefits assistance, mental health services), and (3) either offered HIV tests directly to clients or had a formal referral process for clients who requested or needed HIV tests. Our assumption was that sites that provided any HIV testing (either directly or indirectly through referrals) would be appropriate candidate sites for rapid HIV testing as well.

Sites outside the sampling frame (of private nonprofit community providers for general underserved populations) included public health departments or state-run facilities (e.g., for incarcerated individuals), private practice or for-profit settings, and university health clinics. We also excluded those settings not likely to use HIV testing for prevention purposes (i.e., hospices, inpatient-only organizations, primarily research organizations). Because hospitals face different testing issues and need to develop different types of testing protocols (e.g., for pregnant women) than community clinics and CBOs, we excluded hospitals as well.

Sample Characteristics

Staff at 575 of the 738 sampled sites were successfully reached between November 2005 and March 2006 (78% completion rate of listed sites); 11 of the 738 sites were no longer in existence. Of the 575 sites contacted, 375 sites were eligible and interviews were conducted, and 200 sites were ineligible (ineligibility rate=35% of contacted sites). Multiple unsuccessful attempts were made to interview the 152 noncompleting sites. Table 1 ▶ provides descriptive statistics of the final sample.

TABLE 1—

Characteristics of Community Health Settings Surveyed Regarding Rapid HIV Test Availability: United States, 2003–2006

| Overall (n = 375) | Clinicsa (n = 227) | CBOsb (n = 148) | |

| Community characteristics | |||

| AIDS prevalence of PMSA, mean (SD) | 24 532.2 (46 427.2) | 26 670.5 (48 549.6) | 21 808.0 (42 699.2) |

| Proportion of subgroups in which HIV is increasing, mean (SD) | |||

| Blacks | 26.7 (27.5) | 30.1 (42.2) | 25.5 (43.6) |

| Hispanics | 20.5 (24.6) | 20.3 (32.8) | 14.7 (29.4) |

| In poverty | 17.6 (11.2) | 18.4 (16.5) | 13.4 (17.8) |

| Geographic region, % | |||

| Midwest | 25 | 24 | 32 |

| Northeast | 24 | 27 | 21 |

| South | 29 | 27 | 26 |

| West (Calif) | 22 | 22 | 21 |

| Site characteristics | |||

| Number of unique clients served, % | |||

| < 100 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| 101–2500 | 48 | 43 | 55 |

| 2501–5000 | 18 | 17 | 19 |

| 5001–7500 | 7 | 8 | 5 |

| > 7500 | 25 | 30 | 18 |

| Resources, % | |||

| Has on-site laboratory | 31 | 53 | 2 |

| Has mobile sites | 18 | 22 | 13 |

| Has multiple locations | 65 | 68 | 62 |

| Performs other diagnostic tests | 57 | 86 | 20 |

| Services, % | |||

| General health clinic | 44 | 78 | 0 |

| HIV medical care | 41 | 73 | 0 |

| HIV social services | 71 | 68 | 74 |

| HIV prevention and education | 85 | 90 | 79 |

| STI treatment and prevention | 74 | 92 | 51 |

| Reproductive health | 48 | 75 | 14 |

| Maternal and child health | 46 | 70 | 15 |

| Mental health counseling | 66 | 64 | 67 |

| Substance abuse treatment | 38 | 33 | 44 |

| Housing assistance | 50 | 44 | 58 |

| Food bank | 24 | 22 | 27 |

| Hemophilia services | 8 | 11 | 3 |

Note. CBO = community-based organization; PMSA = primary metropolitan statistical sampling area; STI = sexually transmitted infection.

aNonprofit community health clinics for underserved populations.

bNonclinical AIDS service organizations.

The 375 eligible, interviewed sites represented about half of both source lists (from NIDD and Web-based lists). About half of the sites sampled from the Midwest (55%) and Northeast (47%) were interviewed, whereas 38% of the sites sampled in the South and 66% of the sites sampled in the West were interviewed. This variation was primarily because of a greater-than-expected completion rate in the Los Angeles primary MSA and a lower-than-expected completion rate in the Atlanta primary MSA. Because sites were called in a random order, and no staff member refused participation, this variation across primary MSAs and region was not expected to bias the results significantly.

Reasons for ineligibility included not providing or referring clients for HIV testing (61%; n=122), being a public health department (29%; n=57), not providing direct medical or social services (advocacy or legal aid organizations; 27%; n=54), providing prison health care (1%; n=2), being a research institution (1%; n=2), and being for-profit (5%; n=10). Responding sites could be ineligible for more than 1 reason.

Survey Protocol

Interviewers asked to speak with medical directors or executive directors, who in some cases referred interviewers to another staff member who was knowledgeable about HIV testing within the organization (e.g., HIV services coordinator).

To assess HIV testing, interviewers asked staff about HIV testing procedures, including whether rapid or nonrapid HIV testing was provided, and whether HIV testing was provided directly or by referral. Using defined response categories, rapid test providers indicated when rapid testing was instituted and the specific on-site and off-site settings in which rapid tests were used. Those sites that did not provide the rapid test were asked whether they had concrete plans to implement rapid testing in the next 6 months. Staff at sites that provided referrals only (and not direct testing) were asked about referral procedures.

To assess clinic characteristics, interviewers asked staff about organizational size and resources, including approximate number of clients served (dichotomized with a median split into ≤ 2500 or >2500); whether the site had an on-site laboratory, mobile sites, or other branches, locations, or offices; and whether the site provided other diagnostic tests in addition to HIV tests. Using checklists, staff described services provided by the organization (e.g., direct medical services, social services). Sites that provided direct medical services were categorized as community clinics; all other sites were considered to be CBOs.

The zip code of each community health setting was linked to census data on race/ethnicity and income (i.e., percentage of Blacks, Hispanics, and households below the poverty level). Number of cumulative AIDS cases reported in 2001 for each primary MSA6 was linked to each site.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all study variables, overall and separately for community clinics and CBOs. To assess the prevalence of rapid HIV testing in US private nonprofit urban community health settings, we calculated the proportion of clinics and CBOs that offered rapid HIV testing, of those settings that provided any HIV testing (either on-site or by referral).

Because only a small proportion of CBOs were offering rapid HIV tests, we used logistic regressions to examine the relationships among survey, census, and AIDS prevalence variables and availability of rapid testing among community clinics only. We used bivariate logistic regressions to examine the relationship of each predictor variable separately and a multivariate model to examine the simultaneous contribution of all predictors. Because sample frequency distribution of AIDS prevalence was skewed, the data were log-transformed, and the AIDS prevalence logs were used.

We used sampling weights, calculated as the reciprocal of the overall sampling probability for each observation (i.e., the cumulative number of AIDS cases within each primary MSA), to adjust the sample data to represent the target population of US private, nonprofit, urban community health settings. Sampling weights ensure that weighted data from the sample are representative of the entire reference population and allow for calculations of nationally representative estimates.

We did not use nonresponse weights because all sites on the list were contacted, sites were called in a random order, and no staff member refused participation.

RESULTS

Prevalence and Diffusion of Rapid HIV Testing

Only 17% (unweighted n=72) of the total sample (22% [unweighted n=60] of clinics; 10% [unweighted n=12] of CBOs] was currently providing rapid HIV tests. Of settings not providing rapid HIV tests, 53% (26% of clinics, 82% of CBOs) referred clients to other organizations for testing, 33% (54% of clinics, 10% of CBOs) had no plans to start rapid testing, and 14% (20% of clinics, 8% of CBOs) had concrete plans to implement rapid HIV testing programs in the next 6 months.

Of sites that referred clients to other organizations, 41% (35% of clinics, 43% of CBOs) had formal HIV testing agreements, contracts, or memorandums of understanding with referral organizations, and 36% (39% of clinics, 35% of CBOs) had written referral procedures (e.g., for high-risk clients only).

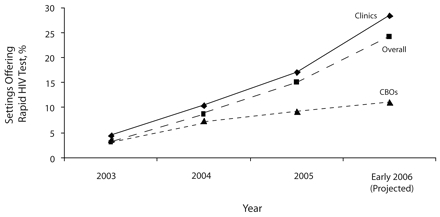

Of the 72 sites that were using rapid HIV tests, most were offering rapid tests in on-site settings, and all were using OraQuick tests (Table 2 ▶). The proportion of the total sample that was providing rapid HIV tests steadily increased from 2003 to 2006 (Figure 1 ▶); the diffusion curve was steeper for clinics than for CBOs. The projected proportion of rapid HIV test providers, based on those who planned to start in the near future, is expected to increase. Diffusion appeared to be at the bottom of the hypothesized S-shaped curve, with only innovators and early adopters represented.

TABLE 2—

Characteristics of Community Health Settings That Were Implementing Rapid HIV Testing: United States, 2003–2006

| Site Characteristic | % of All Test Providers (Overall n = 72) | % of Community Clinica Test Providers (n = 60) | % of CBOb Test Providers (n = 12) |

| Settings of rapid HIV test use | |||

| For occupational health purposes | 42 | 53 | 14 |

| On-site setting | 92 | 90 | 100 |

| Outpatient clinic | 52 | 69 | 3 |

| On-site laboratory | 37 | 49 | 9 |

| Other on-site setting (nonlaboratory, nonclinic) | 57 | 42 | 98 |

| Off-site setting | 43 | 46 | 35 |

| Boothsc | 63 | 53 | 93 |

| Mobile facilityc | 51 | 56 | 35 |

| Streetc | 39 | 23 | 93 |

| Bars or clubsc | 22 | 29 | 100 |

| Types of rapid HIV tests offered | |||

| OraQuick ADVANCE Rapid HIV-1/2 or OraQuick Rapid HIV-1 Antibody Test | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Reveal G2 Rapid HIV-1 Antibody Test | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Multispot HIV-1/HIV-2 Rapid Test | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Uni-Gold Recombigen HIV Test | 1 | 1 | 0 |

Note. CBO = community-based organization. Frequencies are on the basis of organizations directly providing rapid HIV tests (not organizations that refer clients out for testing).

aNonprofit community health clinics for underserved populations.

bNonclinical AIDS service organizations.

cAmong settings that provided off-site testing.

FIGURE 1—

Cumulative percentage of US private, nonprofit, urban community health settings (n = 373) that were offering rapid HIV tests, 2003–2006.

Note. CBOs = community-based organizations (nonclinical AIDS service organizations); Clinics refers to nonprofit community health clinics for underserved populations.

Bivariate and Multivariate Correlates of Rapid HIV Testing in Community Clinics

Nearly all of the factors were significantly related to rapid HIV test availability in bivariate analyses (Table 3 ▶). In the multivariate model, community clinics located in the South (vs West), in areas of higher AIDS prevalence, with on-site laboratories and multiple locations, and that performed diagnostic tests other than HIV tests, had a higher likelihood of rapid HIV testing (Table 3 ▶).

TABLE 3—

Bivariate and Multivariate Correlates of Rapid HIV Testing in 227 US Community Clinics: 2003–2006

| Bivariate Models, OR (95% CI) | Multivariate Model, Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

| Geographic region | ||

| West (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Midwest | 0.49* (0.22, 1.08) | 0.63 (0.24, 1.67) |

| Northeast | 2.36*** (1.27, 4.37) | 1.98 (0.84, 4.62) |

| South | 2.36*** (1.28, 4.35) | 2.87** (1.22, 6.78) |

| Community characteristics | ||

| High AIDS prevalence | 2.14† (1.68, 2.73) | 1.66*** (1.17, 2.34) |

| High proportion of Blacks | 1.01 (1.00, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) |

| High proportion of Hispanics | 1.01 (1.01, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) |

| High proportion living in poverty | 1.04† (1.02, 1.06) | 1.02 (0.99, 1.05) |

| Site characteristics | ||

| Has large client base (> 2500) | 1.66** (1.08, 2.56) | 0.96 (0.56, 1.64) |

| Has on-site laboratory | 3.20† (2.02, 5.06) | 3.10† (1.78, 5.42) |

| Has mobile sites | 2.04*** (1.29, 3.25) | 1.60* (0.92, 2.79) |

| Has multiple locations | 1.85** (1.14, 3.02) | 1.93** (1.05, 3.52) |

| Performs other diagnostic tests | 24.64*** (3.39, 179.25) | 13.35** (1.76, 101.01) |

Note. OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval. Community clinics are nonprofit community health clinics for underserved populations.

* P < .10; **P < .05; ***P < .01; †P < .001.

DISCUSSION

Our findings indicated that rapid HIV tests were infrequently offered in US private, nonprofit, urban community clinics and CBOs. Only 17% of all settings (22% of community clinics, 10% of CBOs) provided rapid HIV tests. More than 40% of the settings referred clients to other organizations for HIV testing, rather than directly offering tests. Results suggest that some CBOs may not have the capacity to provide HIV testing to clients, whether rapid or nonrapid, even if their clients are at risk. Such organizations may instead refer clients to other testing sites. However, the extent to which clients who are referred for HIV testing actually receive test results is unknown. Increased community capacity for same-day, point-of-care HIV testing, especially among CBOs, is critical for realizing CDC goals for universal HIV testing.

In accordance with diffusion of innovation theory,27 organizational resources were robust correlates of rapid HIV testing. Need for HIV testing, operationalized as community factors related to HIV risk, was a less robust predictor than were organizational resources; of the variables representing need, only AIDS prevalence was a significant multivariate correlate. Community clinics with full-service (vs Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–waived only) on-site laboratories and multiple locations that performed diagnostic tests other than HIV were more likely to be providing rapid tests. Moreover, nearly 40% of rapid test providers processed tests in the laboratory, versus at point-of-care. However, all rapid test providers were using Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–waived rapid tests. One of the advantages of Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–waived tests is that they can be used by trained nonlaboratory staff in any venue, including those outside traditional health care. Smaller venues without the capacity to draw blood have the infrastructure for providing Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–waived oral fluid rapid HIV tests. Lack of a full-service laboratory should not be a barrier to rapid testing.

Only 12 CBOs surveyed made rapid HIV testing available to their clients, despite CDC recommendations that CBOs test all at-risk clients.2 Clients of the HIV-focused CBOs in our sample were likely at risk for HIV and would benefit from greater access to rapid HIV testing. Because CBOs tend to be smaller than community clinics, CBOs may have insufficient resources to implement rapid testing programs.

Our survey showed substantial geographic variation in rapid HIV test availability. Community clinics in the South, versus the West (i.e., 3 primary MSAs in California) were more likely to be providing rapid tests. Regional differences may be a consequence of different HIV testing regulatory environments. For example, California has relatively strict regulations for rapid HIV testing. Organizations must apply in writing to the California Department of Health Services for permission to offer Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–waived rapid HIV tests; the backlog of applications in 2005 (during our study) was high (S.L. Kwong, oral communication, California Department of Health Services, July 2005). Removing some of the bureaucratic barriers to testing, including pre-and posttest counseling regulations, may elicit change in state policies and, in turn, increase rapid testing rates.25

Limitations

To our knowledge, our study was the first to examine the availability of rapid HIV testing in private, nonprofit, urban US community health care settings that used a multistage probability sample. Nevertheless, limitations existed. Because all of the sampled organizations in the West were in California, our finding of lower rapid testing in the West may not generalize to the entire region. Our results may have overestimated rates of use, because organizations may not use the test frequently, even if it is available. Further, respondents may not have had complete information about rapid testing at their site, especially regarding subsidiary venues. However, most organizations were relatively small, and the interviewers spoke with the director or were referred to staff members who knew about HIV testing at the organization.

In addition, we may have inadvertently excluded some organizations from our sampling list. However, the list was compiled from and checked against multiple sources that were known to be accurate at the time of the survey. We also may have excluded appropriate organizations for rapid HIV testing through our eligibility criterion that organizations had to be HIV test providers to participate. Finally, our results provided a snapshot of the state of rapid HIV testing shortly after test approval in 2002; additional research is needed that documents rapid testing diffusion after the CDC’s 2006 recommendations have been widely disseminated.

Conclusion

Rapid HIV testing gives community health settings great flexibility to provide testing to high-risk clients who may not routinely visit health care settings. Nevertheless, our survey of a nationally representative sample of private, nonprofit, urban community health settings found low availability of rapid HIV testing overall, especially among CBOs. Future research should investigate the barriers to HIV testing in community health settings, including those related to cost, feasibility, training, staffing, regulatory environment, and resources, especially among community health settings with fewer resources, as well as in mobile testing sites. Streamlined counseling processes recommended by the CDC, such as face-to-face counseling supplemented or replaced by videos or pamphlets,16 may allow smaller organizations to redirect counseling funds for rapid HIV testing programs.25

Development of testing protocols, training materials, and guidelines for mobile sites would further aid diffusion of rapid HIV testing and would encourage greater use of mobile testing sites in communities with high HIV rates.33 Effective means of universal rapid HIV testing are already being used in the developing world, including some countries in Africa.34 With greater resources, rapid HIV testing can also increase in the United States and will ultimately help to realize the CDC’s goal of universal awareness of HIV status in a way that is feasible for and acceptable to both clients and health care providers.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (grant U65/CCU924523-01). Support for preparation of this article was partially provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (grant U48/DP000056) and the California HIV/ AIDS Research Program (grant CH05-618).

We are grateful to David J. Klein for helping with database management, Andy Olds for assistance with data collection, and members of our advisory committee (Sandra Berry, Frank Galvan, Allen Gifford, Lee Hilborne, Seth Kalichman, Peter Kerndt, Steven Pinkerton, and Michael Stoto) for their helpful feedback regarding this article.

Note. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Human Participant Protection The institutional review board of RAND Corp approved this study.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors L.M. Bogart contributed to the conception and design of the study and led the study implementation, interpretation of the results, and writing of the article. D. Howerton contributed to the design of the study and the interpretation of the results, and helped with the writing of the article. J. Lange contributed to the design of the study and interpretation of the results. K. Becker led the data collection component of the study and helped to summarize and interpret study results. C.M. Setodji conducted the statistical sampling and data analysis and helped with data interpretation. S.M. Asch led the conception and design of the study and helped with the study implementation, interpretation of the results, and writing of the article.

References

- 1.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Revised guidelines for HIV counseling, testing, and referral. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2001;50:1–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glynn M, Rhodes P. Estimated HIV prevalence in the United States at the end of 2003. Paper presented at: National HIV Prevention Conference; June 12–15, 2005; Atlanta, Ga.

- 4.Advancing HIV Prevention. Interim Technical Guidance for Selected Interventions. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2003.

- 5.Bulterys M, Jamieson DJ, O’Sullivan MJ, et al. Rapid HIV-1 testing during labor: a multicenter study. JAMA. 2004;292:219–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV and AIDS—United States, 1981–2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50:430–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delaney KP, Branson BM, Uniyal A, et al. Performance of an oral fluid rapid HIV-1/2 test: experience from four CDC studies. AIDS. 2006;20:1655–1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wesolowski LG, MacKellar DA, Facente SN, et al. Post-marketing surveillance of OraQuick whole blood and oral fluid rapid HIV testing. AIDS. 2006; 20:1661–1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenwald JL, Burstein GR, Pincus J, Branson B. A rapid review of rapid HIV antibody tests. Curr Inf Dis Rep. 2006;8:125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.OraQuick advance rapid HIV1–2 antibody test [package insert]. Bethlehem, Pa: OraSure Technologies; 2004.

- 11.HIV 1/2 STAT-PAK Assay [package insert]. Medford, NY: Chembio Diagnostic Systems Inc; 2006.

- 12.Uni-Gold Recombigen® HIV [package insert]. Wicklow, Ireland: Trinity Biotech PLC; 2004.

- 13.Henn M, Begier E, Sepkowitz KA, Kellerman S. Less talk and more testing: how NYC has increased HIV testing. Presented at: XVI International AIDS Conference; August 13–18, 2006; Toronto, Ontario.

- 14.Hutchinson AB, Branson BM, Kim A, Farnham PG. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of alternative HIV counseling and testing methods to increase knowledge of HIV status. AIDS. 2006;20:1597–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liang TS, Erbelding E, Jacob CA, et al. Rapid HIV testing of clients of a mobile STD/HIV clinic. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2005;19:253–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mugavero M, Sullivan C, Shaheen A, et al. Feasibility of routinely offered HIV testing among diverse socio-demographic clinic populations. Presented at: XVI International AIDS Conference; August 13–18, 2006; Toronto, Ontario.

- 17.Randall L, Berk W. Effective HIV case identification through routine HIV testing in clinical settings in Michigan. Presented at: XVI International AIDS Conference; August 13–18, 2006; Toronto, Ontario.

- 18.Richey S, Lockett G, Mathai S. HIV rapid testing: an approach to stemming HIV/AIDS in the African American communities of Alameda County with respect to the local state emergency. Presented at: XVI International AIDS Conference; August 13–18, 2006; Toronto, Ontario.

- 19.San Antonio-Gaddy M, Richardson-Moore A, Burstein GR, Newman DR, Branson BM, Birkhead GS. Rapid HIV antibody testing in the New York State Anonymous HIV Counseling and Testing Program: experience from the field. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:446–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spielberg F, Branson BM, Goldbaum GM, et al. Choosing HIV counseling and testing strategies for outreach settings: a randomized trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38:348–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kendrick SR, Kroc KA, Withum D, Rydman RJ, Branson BM, Weinstein RA. Outcomes of offering rapid point-of-care HIV testing in a sexually transmitted disease clinic. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005; 38:142–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metcalf CA, Douglas JM Jr, Malotte CK, et al. Relative efficacy of prevention counseling with rapid and standard HIV testing: a randomized, controlled trial (RESPECT-2). Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:130–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Notice to readers: protocols for confirmation of reactive rapid HIV tests. MMWR. 2004;53:221–222.15717396 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galvan FH, Brooks RA, Leibowitz AA. Rapid HIV testing: issues in implementation. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2004;18:15–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Leibowitz AA, Etzel MA. Routine, rapid HIV testing. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006; 18:273–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Health Research and Educational Trust. Map to HIV testing laws of all US states. Available at: http://www.hret.org/hret/about/hivmap.html. Accessed May 9, 2007.

- 27.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th ed. New York, NY: Free Press; 2003.

- 28.Frankel MR, Shapiro MF, Duan N, et al. National probability samples in studies of low-prevalence diseases. Part II: Designing and implementing the HIV cost and services utilization study sample. Health Serv Res. 1999;34(5 pt 1):969–992. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shapiro MF, Berk ML, Berry SH, et al. National probability samples in studies of low-prevalence diseases. Part I: Perspectives and lessons from the HIV cost and services utilization study. Health Serv Res. 1999;34(5 pt 1):951–968. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cochran WG. Sampling Techniques. 3rd ed. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 1977.

- 31.Kish L. Survey Sampling. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 1965.

- 32.Demonstration Projects for Community-Based Organizations (CBOs): HIV Rapid Testing in Nonclinical Settings. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2005.

- 33.Reyes ADL. Providing rapid HIV counseling, testing and referral (CTR) services at offsite locations. Presented at: XVI International AIDS Conference; August 13–18, 2006; Toronto, Ontario.

- 34.Steen TW, Seipone K, Gomez Fde L, et al. Two and a half years of routine HIV testing in Botswana. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:484–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]