Abstract

CRACM1 (Orai1) constitutes the pore subunit of CRAC channels that are crucial for many physiological processes 1-6. A point mutation in CRACM1 has been associated with SCID disease in humans 2. We have generated CRACM1 deficient mice using gene trap, where β-galactosidase (LacZ) activity identifies CRACM1 expression in tissues. We show here that the homozygous CRACM1 deficient mice are considerably smaller in size and are grossly defective in mast cell degranulation and cytokine secretion. FcεRI-mediated in vivo allergic reactions were also inhibited in CRACM1-/- mice. Other tissues expressing truncated CRACM1-LacZ fusion protein include skeletal muscles, kidney and regions in the brain and heart. Surprisingly, no CRACM1 expression was seen in the lymphoid regions of thymus. Accordingly, we found no defect in T cell development. Thus, our data reveal novel crucial roles for CRAC channels including a putative role in excitable cells.

Introduction

Receptor stimulation in most non-excitable cells results in a biphasic rise in cytosolic calcium. The initial transient rise is due to IP3 mediated release of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). The subsequent prolonged increase requires calcium influx through the store-operated channels (SOCs) in the plasma membrane (PM). In cells of the immune system, store operated-calcium release activated calcium (CRAC) channels are the predominant mode of sustained calcium signaling. CRAC currents were discovered in rat peritoneal mast cells 7 and have since been extensively characterized in these and other cell types 8. However, most studies have not specifically addressed a requirement for transient (ER mediated) vs prolonged (CRAC mediated) cytosolic Ca2+ rise in mast cell physiology and effector functions.

Mast cells express the high affinity receptor for IgE, FcεRI. Crosslinking of FcεRI activates two parallel signaling pathways initiated by Fyn and Lyn kinases. These pathways activate PKC (via Fyn-Gab2-PI3K) and ER calcium release (via Lyn-Syk-LAT-SLP76-Vav1) respectively 9-12. PKC and Ca2+ in turn synergize to stimulate mast cell degranulation. Specifically, cytosolic Ca2+ binds a family of calcium sensors, known as synaptotagmins (syt) and initiates their oligomerization 13. Ca2+ binding also promotes the interaction of syt with syntaxin and SNAP-25 localized in the plasma membrane. These events lead to SNARE assembly and membrane fusion of secretary granules, resulting in the release of preformed mediators such as histamine, serotonin, and the initial release of TNF-α 13. In addition, mast cells secrete de novo synthesized lipid mediators, chemokines and inflammatory cytokines. The role of Ca2+ in these mast cell effector functions remains less well studied.

Here we have generated CRACM1 deficient mice using gene trap with the aim of analyzing the physiological role of CRAC channels. We find that CRACM1 is crucial for degranulation, synthesis of lipid mediators as well as cytokine release in the mast cells. Furthermore, CRACM1-/- mice are deficient in the induction of in vivo allergic responses.

CRACM1 has earlier been shown to play a crucial role in T cell proliferation and cytokine secretion in one type of SCID 14. Some of these SCID patients also had a rudimentary thymus with a severely depleted lymphoid compartment 14. Surprisingly, CRACM1-/- mice showed no defect in thymic cellularity and T cell development. Our preliminary analysis also did not show a significant defect in T cell proliferation in CRACM1-/- mice. However, IL-2 and IFN-γ secretion were found to be inhibited.

Apart from immune cells, a general role for store-operated calcium entry has been proposed in pancreatic acinar cells, hepatocytes, certain types of excitable cells including neurons, smooth muscle cells, endocrine and neuroendocrine cells 8. Most of these studies however do not specifically demonstrate a role for CRAC channels. The two SCID patients with mutated CRACM1 also suffered from unexplained congenital non-progressive myopathy 2. We detected the expression of LacZ-CRACM1 fusion protein in several excitable cells, particularly skeletal muscles, suggesting a specific role for CRAC.

Results

Generation of CRACM1-/- mice and tissue expression

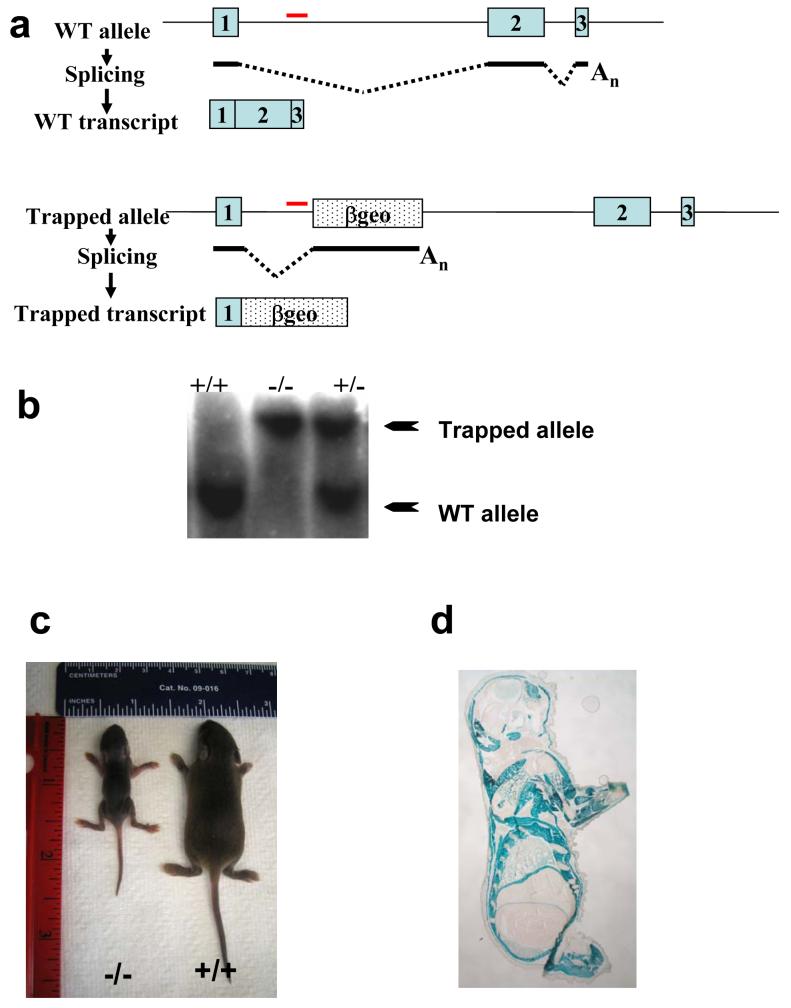

CRACM1 deficient mice were generated using Genetrap 15. As shown in Fig. 1a, the gene-trapping cassette was inserted in the 1st intron in the ES cells (Fig. 1a). For genotyping CRACM1-/- mice, a gene specific probe was designed with in the first intron. Fig. 1b shows the targeted and WT bands on a representative southern blot. Initially, we failed to get any homozygous knockout (-/-) pups. However, special housing conditions ensured the survival of CRACM1-/- mice that were considerably smaller in size until maturity (Fig. 1c). Expected mendelian ratios of WT, +/- and -/- pups were obtained upon splitting and fostering of the (+/- X +/-) litters to house no more than 3-4 pups per dam. A whole body necropsy and an extensive histological analysis on CRACM1-/- mouse pups did not reveal any obvious abnormality (data not shown).

Figure 1. Generation of CRACM1 Mutant Mice Using Gene Trap.

(a) Schematic representation of trapped CRACM1 gene in the ES cells. Blue boxes represent exons. Dotted box labelled ‘βgeo’ shows the site of gene trap vector insertion. The trapped transcript would result in the generation of truncated CRACM1-LacZ fusion protein. (b) Southern blot showing screening of CRACM1-/- mice using a gene specific probe. Red line depicts the site of probe hybridization. The size of WT allele is 11kb and that of trapped allele is 19.5kb. (c) Picture showing 10 day old CRACM1-/- mouse (left) with a WT littermate (right). (d) LacZ staining to detect the tissue distribution of CRACM1 protein. Neonatal (1 Day old) CRACM1-/- pups were cryo-sectioned and stained O/N with X-Gal.

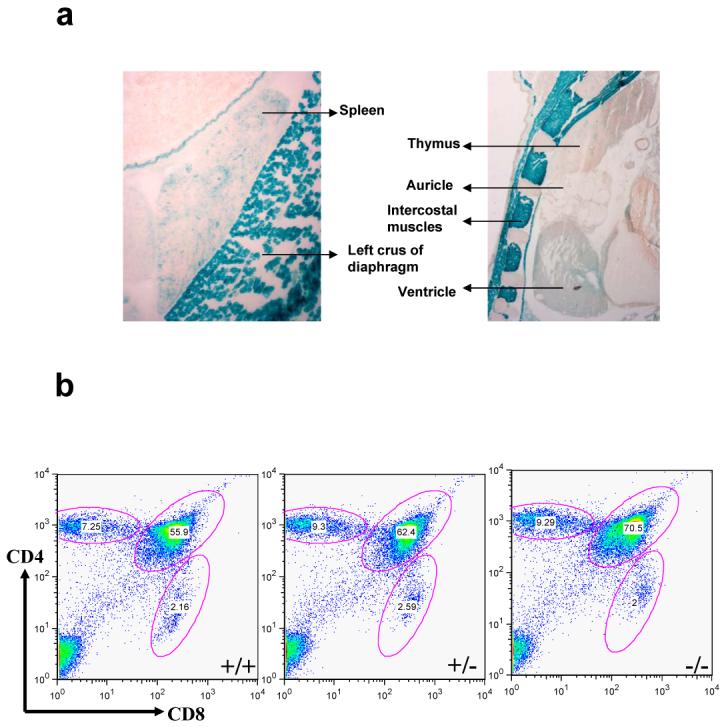

To identify novel physiological roles for CRAC and to determine the reason for the overall smaller size of CRACM1-/- mice, we performed LacZ staining on newborn knockout and WT pups (Fig. 1d). To our surprise, robust expression of mutant CRACM1-LacZ fusion protein was seen in almost all the skeletal muscles. Kidneys stained positive in three different regions. Varied expression was seen in different regions of the brain. Some parts of the heart also showed faint expression (Suppl. Table S1). Since CRAC channels are known to be indispensable primarily for non-excitable cells, these observations raise the interesting possibility of a crucial role for CRAC channels in excitable cells, particularly skeletal muscles. Suppl. Table S1 summarizes the list of tissues that stained with X-Gal.

CRACM1 is required for mast cell effector functions

Since CRAC channels have been studied extensively in mast cell lines, we sought to analyze the precise role of CRAC mediated calcium influx in mast cell effector functions. To derive mast cells, E15.5 fetal liver suspensions were cultured with IL-3 and SCF for 5 weeks. At the end of 5 weeks and before each assay, cells derived from CRACM1 +/+, +/- and -/- fetal livers were counted and stained with anti-FcεRI-α (Suppl. Fig. S1a). The cell yields and levels of FcεRI expression were found to be comparable in all three groups suggesting that in vitro mast cell proliferation and differentiation is not affected by CRACM1 deletion. Monomeric IgE binding to FcεRI, in the absence of antigen, increases expression of the receptor 16. CRACM1 +/+, +/- and -/- mast cells incubated overnight (O/N) with IgE showed comparable up-regulation of FcεRI (Suppl. Fig. S1b).

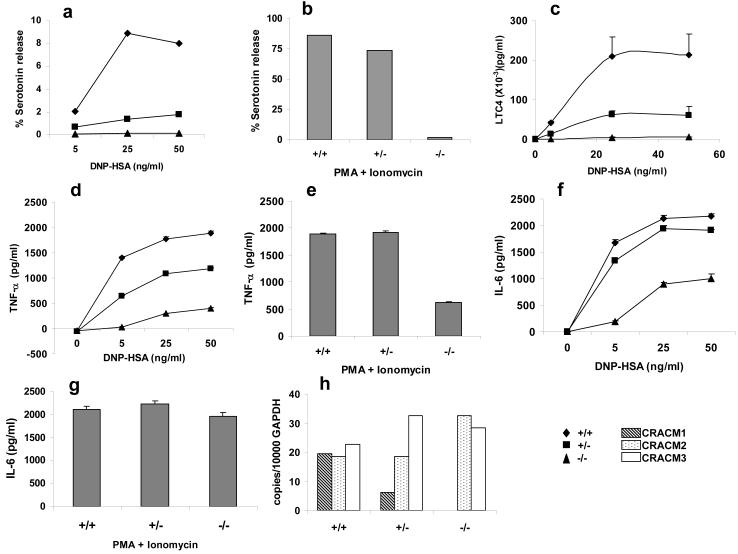

To study the effect of CRACM1 deletion on mast cell degranulation, cells were loaded with 3H serotonin and DNP specific IgE O/N. The following day, cells were washed and incubated with titrating doses of DNP-HSA for 20 min. As shown in Fig2a, serotonin release was abolished in CRACM1-/- mast cells and much reduced in CRACM1+/-, in response to antigen mediated cross-linking of FcεRI. CRACM1-/- cells also showed a complete inhibition in response to saturating doses of PMA (a PKC agonist) and Ionomycin (which depletes Ca2+ stores to activate ICRAC) 17, while the response was intact in CRACM1+/- cells (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2. CRACM1 deletion in mast cells strongly suppresses degranulation and LTC4 synthesis but affects cytokine secretion differentially.

Serotonin release from CRACM1 +/+ (diamonds), +/- (squares) and -/- (triangles) mast cells loaded with anti- DNP IgE (0.5μg/ml) and stimulated either with 50, 25, 5 and 0 ng/ml of DNP-HSA to induce FcεRI cross-linking (a) or PMA (1.5μg/ml) plus Ionomycin (2μM) (b) for 15min. Results are expressed as percentage of total serotonin uptake (values represent pooled triplicates from 1 experiment, representative of n=3). (c) LTC4 secretion induced by FcεRI aggregation as in panel a (results are mean ± SEM of triplicates, from 1 experiment, representative of n=2). TNF (d, e) and IL-6 (f, g) secretion by cells loaded with anti-DNP IgE (0.5μg/ml) and stimulated either with 50, 25, 5 and 0 ng/ml of DNP-HSA (d, f) or PMA (1.5μg/ml) plus Ionomycin (2μM) (e, g) for 6 hrs. (h) Real time PCR showing CRACM1, CRACM2 and CRACM3 mRNA levels in mast cells derived from CRACM1 +/+ (hashed bars), +/- (dotted bars) and -/- (open bars) littermates.

Serotonin is stored in preformed granules and released upon mast cell activation whereas arachidonic acid metabolites are synthesized de novo. We next investigated whether CRACM1 deletion affected the synthesis of LTC4. Cells were incubated with DNP specific IgE O/N, stimulated with different doses of DNP-HSA for 30min and LTC4 levels were measured in the supernatants. Fig. 2c shows that LTC4 secretion in response to FcεRI aggregation was abolished in -/- and much reduced in +/- mast cells.

Given the above results, we set out to investigate the impact of CRACM1 deficiency on cytokine secretion by mast cells. TNF-α is stored in granules as well as synthesized de novo upon FcεRI triggering, whereas IL-6 is synthesized upon triggering. Expression of mast cell-derived TNF-α has been shown to be dependent on NFATc1 and NFATc2 activity 18 whereas IL-6 has been shown to require NFκB nuclear translocation 19. As shown in Fig 2 d and e, CRACM1-/- mast cells showed ∼75% decrease in the production of TNFα in response to different doses of antigen as well as PMA/Ionomycin stimulation. CRACM1+/- mast cells also showed ∼25% decrease to antigen stimulation but the response to PMA/Ionomycin was comparable to WT mast cells. IL-6 secretion by CRACM1-/- mast cells showed a decrease of ∼50% in response to antigen but no decrease was seen with PMA/Ionomycin stimulation. WT and CRACM1+/- mast cells showed comparable IL-6 secretion at all antigen doses (Fig. 2 f and g).

Taken together, these results suggest that CRACM1 is indispensable for mast cell degranulation and secretion of lipid mediators. However, cytokine production is differentially affected.

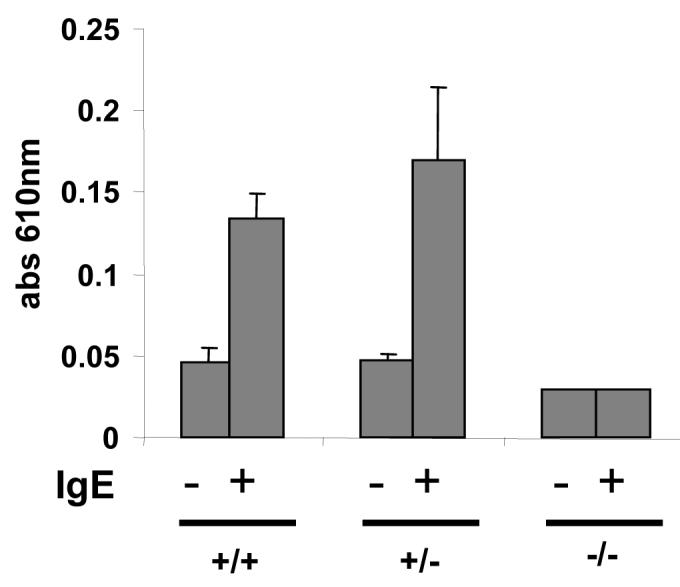

CRACM1 deficiency suppresses passive cutaneous anaphylaxis in mice

The in vivo IgE-mediated model of passive cutaneous anaphylaxis (PCA) requires mast cells 20. We next assessed the efficacy of CRACM1 knockdown in suppressing allergic reactions involving normal tissue resident mast cells using PCA. DNP-specific IgE was injected into left ears of the WT and CRACM1-/- littermates and right ears were injected with saline. 24 hrs later, an immediate-type allergic reaction was induced by i.v. injection of the antigen (DNP-HSA) and Evan’s Blue dye. In PCA, mast cell activation through FcεRI results in the release of several vaso-active substances, which increase vascular permeability. This effect can be quantified by local accumulation of the Evan’s Blue dye leaving the vessels in the IgE sensitized area. 60 min after the injection of antigen, mice were sacrificed and dye was extracted from the ears as described before 21. As shown in Fig. 3, IgE-dependent PCA reactions were abolished in CRACM1-/- mice similar to what we saw in mast cell degranulation.

Figure 3. CRACM1 deletion suppresses passive cutaneous anaphylaxis (PCA) reaction in mice.

Mice were sensitized intra-dermally with 25 ng anti-DNP IgE in the left ears and with saline in the right ears. 24 h later PCA was induced by i.v. injection of DNP-HSA along with 2% Evan’s Blue dye. 60 min post injection, mice were sacrificed and ears were excised. Evan’s Blue was extracted and quantified by absorbance at 610 nm. The results are expressed as mean ± STD.

Store-operated calcium influx and ICRAC in mast cells

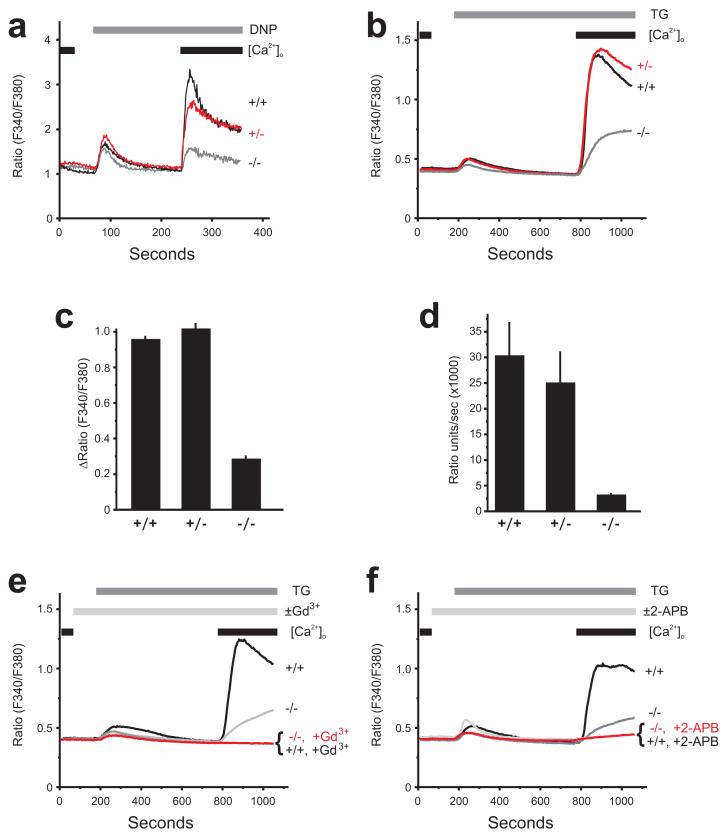

We sought to correlate the functional defect that we observed in CRACM1-/- mast cells with the level of receptor stimulated and store-operated calcium influx in these cells. We first measured the effect of CRACM1 deletion on calcium release and influx in response to antigen mediated FcεRI-crosslinking using Fura-2. As shown in Fig. 4a, the ER Ca2+ release was comparable in all three mast cell populations (wildtype, +/+; CRACM1 +/-; CRACM1 -/-). Calcium influx was inhibited by ∼70% in CRACM1-/- cells but only 10-20% in CRACM1 +/- cells. To verify that the residual calcium influx was indeed store operated, a SERCA inhibitor thapsigargin (TG) was used to deplete the stores. Cells were loaded with the fluorescent calcium indicator, Fura-5F and bathed in HEPES buffered salt solution (HBSS) containing 1mM extracellular calcium ([Ca2+]o). The changes in intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) were measured at the single cell level. TG treatment induced a store-activated Ca2+-entry in all three cell populations (Fig. 4b). However, while wildtype +/+ and CRACM1 +/- cells displayed similar peak Ca2+-entry (Fig. 4c) and rate of Ca2+-entry (Fig. 4d), these properties were deficient in CRACM1 -/- cells, but not absent. In both wild type +/+ and CRACM1 -/- cells, the observed TG-induced Ca2+ entry was completely blocked by inhibitors of CRAC currents, either 1 μM Gd3+ (Fig. 4e) or 30 μM 2-APB (2-aminoethyldiphenyl borate) (Fig. 4f), indicating that the residual Ca entry was CRAC mediated.

Figure 4. Store-operated Ca2+ influx is significantly reduced but not entirely abolished in CRACM1-/- mast cells.

(a) Calcium influx measured in response to FcεRI aggregation with 25ng/ml of DNP-HSA in cells pre-loaded with anti-DNP IgE (0.5μg/ml) (representative of 3 experiments). Mast cells derived from CRACM1 +/+ (thick black), +/- (thick grey), -/- (thin black) were loaded with Fura-2AM, re-suspended in a zero calcium buffer ([Ca2+]o) and stimulated as shown. (b) Fura-5F-loaded mast cells were treated with 2 μm thapsigargin (TG) under nominally-Ca2+-free conditions for 10 minutes after which extracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]o) was restored to 1mM to observe Ca2+-entry (mean of 3 experiments). The peak Ca2+-entry response (ΔRatio =peak ratio-basal ratio) and the maximal rate of Ca2+ entry (Ratio units/sec) for each mast cell population were calculated and presented in (c) and (d) respectively (mean ± SEM of 3 experiments). (e) Using the same protocol as in (b), the effects of 1 μm Gd3+ (e; mean of 4 experiments) and 30 μm 2-APB (f; mean of 3 experiments) on thapsigargin-activated Ca2+ influx were observed on wild type +/+ and CRACM1 -/- primary mast cells.

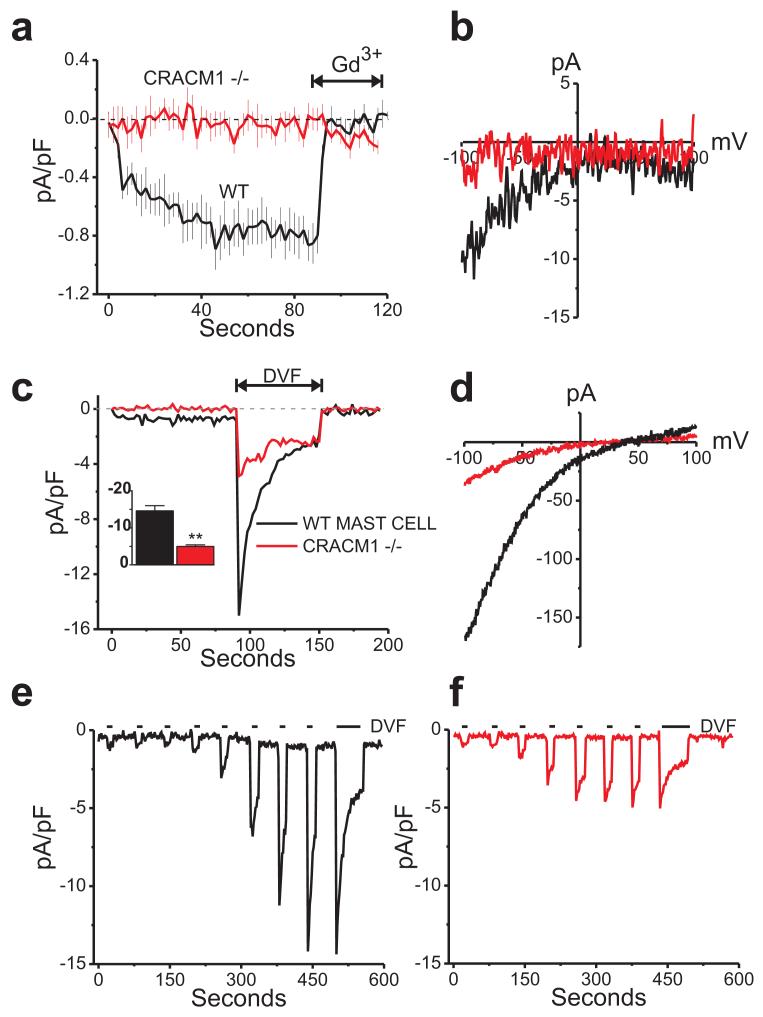

We also measured the CRAC currents (ICRAC) in mast cells. Whole-cell store-operated Ca2+ currents were measured using a pipet solution containing IP3 and BAPTA (1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy) ethane-N,N,N’,N’-tetraacetic acid), a calcium-specific chelator, to actively deplete intracellular Ca2+ stores. Fig. 5a and b depict inwardly rectifying currents with densities of -0.85 ± 0.13 pA/pF (black trace) as seen in wildtype mast cells bathed in HBSS containing 20 mM Ca2+. This current was completely abolished by 3 μM Gd3+. However, mast cells from CRACM1-/- mice completely lacked detectable Ca2+ CRAC currents (red trace). Since Ca2+ imaging experiments (Fig. 4) showed a small residual store-operated Ca2+ entry in CRACM1-/- mast cells, we considered the possibility that a small component of ICRAC might remain that was not readily detectable due to the very small size of the Ca2+ ICRAC. We therefore employed a protocol using a divalent cation-free (DVF) extracellular solution, which amplifies very small ICRAC into a more readily detectable range 22. Fig. 5c shows in wildtype mast cells, a peak Na+ ICRAC develops in the range of -14.57 ± 1.41 pA/pF (black trace). Interestingly, in the CRACM1 knockout mast cells, Na+ CRAC currents were also detected, with current densities of -4.95 pA/pF (red trace), albeit significantly less than the WT cells. Nonetheless, these Na+ currents were also inwardly rectifying, characteristic of CRAC channels (Fig. 5d).

Figure 5. CRACM1-/- mast cells show small store-operated CRAC currents.

(a) Mean (± SE) time courses of store-operated current development in WT (black trace) and CRACM1 knockout mast cells (red trace). Whole cell currents were recorded from 0 to - 100 mV voltage steps and were activated with BAPTA and 20 μM IP3 in the pipet. 3 μM Gd3+ was added as indicated. (b) Current-voltage relationship recorded from wildtype (black trace) and CRACM1 -/- (red trace) mast cells under 20 mM Ca2+ conditions identical to the recordings shown in panel (a). (c) Small but detectable store-operated currents in CRACM1 knockout mast cells revealed by switching to divalent free solutions. Inset bar graph shows a significant reduction in the peak Na+ CRAC currents seen in the knockout cells as compared to the wildtype mast cells (unpaired t test, n=10 for each condition). (d) Current-voltage relationship of the traces shown in panel (c) taken at the peaks of the Na+ currents and showing the inward rectification of the store-operated currents in both the wildtype and CRACM1 -/- mast cells. (e, f) Typical passive depletion experiments confirming both the wildtype (black trace) and CRACM1 -/- (red trace) currents were indeed store-operated.

In order to verify that the currents seen in the CRACM1-/- cells were indeed store-operated, passive store-depletion experiments were performed using only BAPTA (to chelate cytosolic Ca2+) in the pipet. Divalent free (DVF) solutions were focally applied intermittently, in order to detect current development in the CRACM1 knockout cells. Figure 5e shows a representative wildtype mast cell recording in which CRAC current develops after a delay due to slow depletion of internal Ca2+ stores under these conditions. Importantly, in the CRACM1 knockout mast cells, the inwardly rectifying currents seen in active store depletion experiments were also detected in the passive store depletion experiments (Fig. 5f). Peak Ca2+ and Na+ current densities were very similar to actively depleted counterparts shown in Fig. 5a, b and Fig. 5c, d respectively. These data suggest that the small Ca2+ influx and ICRAC is presumably due to the other CRACM homologs.

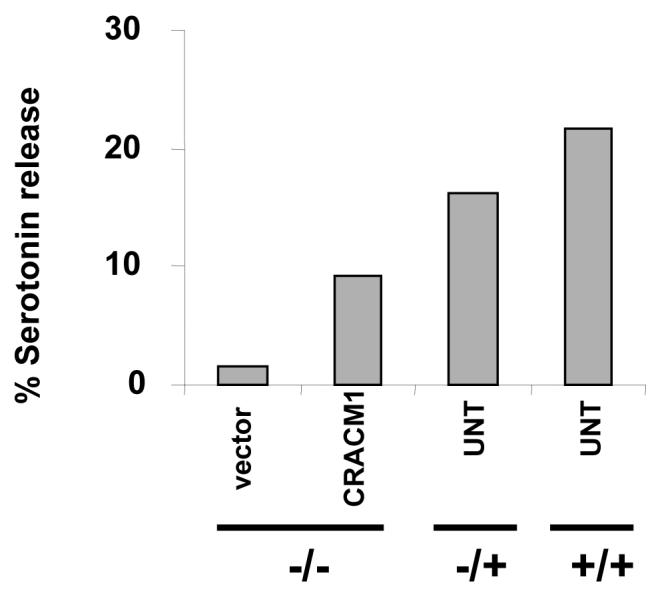

Reconstitution of CRACM1-/- cells with WT-CRACM1 reverses the defect in degranulation

Finally, we wanted to see whether the functional defect seen in CRACM1-/- mast cells could be reconstituted with the expression of WT-CRACM1. To analyze this, we reconstituted CRACM1-/- mast cells with a bicistronic retrovirus expressing WT-CRACM1 and GFP. The reconstitution efficiency of CRACM1-/- mast cells was between 25-30% as seen by GFP expression (Suppl. Fig. S2). CRACM1-/- mast cells reconstituted with WT-CRACM1 showed a reversal in the inhibition of serotonin release when stimulated with PMA/Ionomycin. Recovery of degranulation was commensurate with the efficiency of reconstitution (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Reconstitution of CRACM1-/- mast cells with WT-CRACM1 reverses the defect in degranulation.

Serotonin release from CRACM1-/- mast cells reconstituted with WT-CRACM1 expressing retrovirus (CRACM1-MIGW) or empty vector (MIGW). CRACM1+/+, +/- and the reconstituted -/- mast cells were stimulated with PMA (1.5μg/ml) plus Ionomycin (2μM) for 20 min. Results are expressed as percentage of total serotonin uptake.

T lymphocyte development and effector function

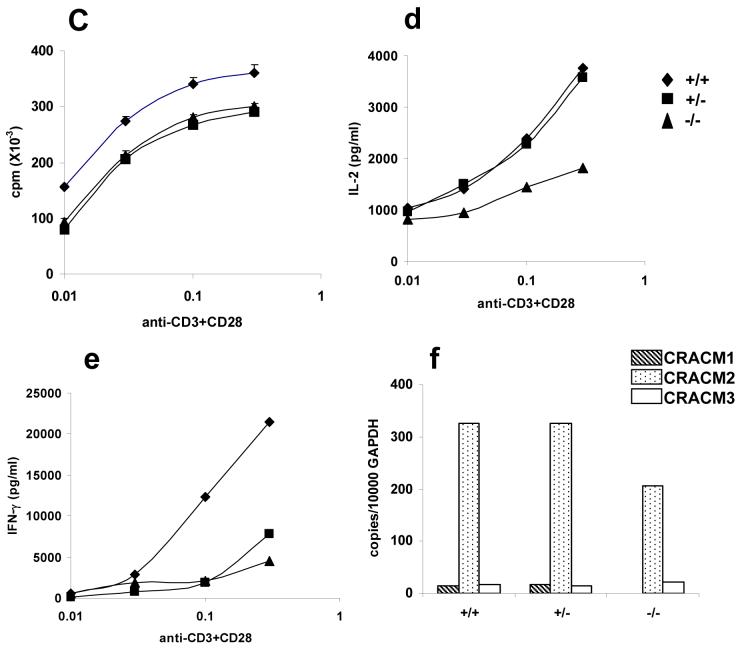

CRACM1 has earlier been shown to be important for T lymphocyte proliferation and effector functions in humans 14, therefore, it was surprising to see no LacZ staining indicative of CRACM1 protein expression in the lymphoid areas of thymus (Fig. 7a). Spleen showed only a few faint spots of staining. Since the CRACM1 deficient SCID patients were also reported to have a rudimentary thymus 14, we stained thymi extracted from 5 week old littermates for CD4 and CD8 antigens. No difference was seen in the percentages of CD4-CD8 double positive and CD4 and CD8 single positive thymocytes (Fig. 7b). The proportions of T and B cells in the spleen were also found to be comparable suggesting an absence of defect in the migration of mature T cells from the thymus (data not shown). Proliferation of CRACM1-/- splenic T cells in response to anti-CD3/anti-CD28 mediated stimulation was not significantly different compared to CRACM1+/- and WT cells (Fig. 7c). However, IL-2 and IFN-γ secretion by CRACM1-/- cells was found to be inhibited when compared with WT and CRACM1+/- T cells (Fig. 7d, e). The lack of effect of CRACM1 deletion on thymocyte development is consistent with the absence of CRACM1-LacZ expression in the thymic lymphoid areas. However, it is possible that the levels of X-gal stain do not correlate with the levels of WT CRACM1 protein expression in tissues. To rule out this possibility, we performed a real-time PCR on mRNA extracted from CRACM1 +/+, +/- and -/- littermate thymocytes. CRACM1 expression was indeed negligible in the thymus as was the expression of CRACM3. However, we found a significantly higher expression of CRACM2 (Fig. 7f). These data suggest that CRACM1 does not play a crucial role in T cell development in mice.

Figure 7. CRACM1-/- mice have normal T cell development and proliferation but cytokine secretion is inhibited.

(a) High resolution images of LacZ stained thymus and spleen of 1 day old CRACM1-/- neonates showing absence of staining in thymic lymphoid areas. Staining was done as described in Figure 1d. (b) Thymus staining for CD4 and CD8 antigens. Thymocytes harvested from 5 week old CRACM1 +/+ (left), +/- (middle) and -/- (right) littermates were stained with CD4-PE-Cy5 and CD8-FITC and analyzed using flowcytometry (c) Proliferation of CRACM1 +/+ (diamonds), +/- (squares) and -/- (triangles) splenocytes. Splenocytes were stimulated with different doses of anti-CD3 + anti-CD28 antibodies for 48 hrs and pulsed with 3H-thymidine for the last 6 hrs. Results are mean ± SEM of triplicates, representative of n=4. (d) IL-2 and (e) IFN-γ secretion by CRACM1 +/+ (diamonds), +/- (squares) and -/- (triangles) splenocytes stimulated as described in Fig. 2c. 48 hrs post-stimulation supernatants were collected and cytokine levels estimated. Results are from pooled triplicates, representative of n=4. (f) Real time PCR for CRACM1, CRACM2 and CRACM3 mRNA in thymocytes isolated from CRACM1 +/+ (hashed bars), +/- (dotted bars) and -/- (open bars) littermates.

Discussion

Mast cells have long been known as critical effectors of allergic disorders. However, recently they are being recognized for many crucial functions at the interface of innate and adaptive immune responses. In order to carry out such diverse effector functions mast cells employ a varied range of effector mechanisms including degranulation of preformed secretary granules (SG) and secretion of chemokines, inflammatory cytokines and leukotrienes. We have shown here that the pore forming subunit of CRAC channels, CRACM1, is crucial for mast cell degranulation, LTC4 secretion, as well as TNF-α secretion (Fig. 2). Furthermore, we show that the induction of the IgE mediated in vivo passive anaphylaxis response is also dependent on CRACM1 (Fig. 3). The secretion of IL-6 is however only partially affected in CRACM1-/- mast cells.

Ca2+ has earlier been shown to be crucial in mast cell effector functions in countless studies 23. The resting cytosolic Ca2+ levels in most non-excitable cells are close to 100nM. ER calcium release brings about a transient 2-3 fold increase whereas store-dependent Ca2+ influx raises the cytosolic levels by almost 10 fold. Therefore, it is likely that different amplitudes of cytosolic Ca2+ rises activate distinct signaling pathways in mast cells thereby allowing the execution of various effector functions. A role for sustained Ca2+ rise in mast cell secretion was demonstrated long ago 24, 25, however the ion channel performing this function had not been identified until recently. The identification of CRACM1 as the pore forming subunit of CRAC channels has allowed us to directly test the role of CRAC channel mediated influx in mast cell effector functions 1-6.

CRACM1 deletion completely abolished mast cell degranulation in response to antigen mediated crosslinking of FcεRI as well as saturating doses of PMA/Ionomycin (Fig. 2). Since the ER mediated transient rise in cytosolic Ca2+ was unaffected by CRACM1 deletion (Fig. 4) our results demonstrate a specific role for CRAC mediated Ca2+ influx in degranulation. What is the precise role of CRAC mediated Ca2+ influx? Ca2+ serves as a critical signal for exocytosis by binding C2 domains (C2A and C2B) of synaptotagmins (syt), a family of calcium sensors that have emerged as key players in membrane fusion in cells capable of regulated secretion such as mast cells and neurons 13, 26. In synaptic vesicle fusion, syt is associated with the vesicles and interacts with the tSNAREs in a Ca2+ independent fashion. tSNAREs are arranged ring-wise around the future fusion site 27. Upon Ca2+ influx and subsequent Ca2+ binding by syt1, the C2A and C2B domains penetrate the plasma membrane, resulting in the local induction of positive membrane curvature under the SNARE complex ring and reduction of distance between the two membranes 28.

Secretion of de novo synthesized lymphokines and lipid mediators by mast cells is independent of degranulation (with the exception of TNF-α, some of which is stored in granules and remaining is synthesized de novo). Therefore, inhibition of LTC4, TNF-α and IL-6 secretion may involve a different event or signaling pathway. In mast cells, TNF-α secretion requires activation and nuclear translocation of NFAT 18. CRAC dependent Ca2+ rise is crucial for the nuclear translocation of NFAT proteins in T lymphocytes 29, 30. Since PMA/Ionomycin stimulated CRACM1-/- mast cells also showed negligible TNF-α secretion, it is reasonable to conclude that CRACM1 deletion affects TNF-α secretion by inhibiting ICRAC-induced NFAT activation.

CRACM1-/- mast cells showed only a partial inhibition of IL-6 secretion. Unlike TNF-α, IL-6 secretion requires NFκB activation 19. Although NFκB is also dependent on cytosolic Ca2+ rise for nuclear translocation, the strength of signal through the receptor required for its activation has been shown to be less stringent at least in T lymphocytes 31. In T cells, the strength of signal through the T cell receptor (TCR) determines the frequency of cytosolic calcium ([Ca2+]i) oscillations. While NFAT nuclear translocation requires oscillations with periods less than approx. 6 min, NFκB is considerably less stringent, showing activity even at much longer interspike intervals of 30 min 31. Thus the activation of NFAT vs NFκB is determined by the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations, which in turn can be translated into the activation of specific cytokine gene enhancers. Similarly, depending on the level of FcεRI occupancy, distinct signaling pathways have been shown to be invoked, resulting in the secretion of different chemokines and cytokines 32. The small store-operated calcium influx seen in CRACM1-/- cells therefore might be sufficient to partially activate NFκB which manifests in the form of submaximal IL-6 secretion.

The source of residual store-operated calcium influx (Fig. 4 and 5) could be the other two homologs of CRACM. To test this possibility, we performed a real-time PCR on mRNA isolated from WT and CRACM1-/- mast cells (Fig 2h). Interestingly, all the three CRACM homologs were found to be expressed at comparable levels in WT mast cells. We found a modest up-regulation of CRACM2 mRNA in CRACM1-/- cells which may account for the small store-operated calcium influx, CRAC currents and partial activation of IL-6 seen in CRACM1-/- mast cells. Intriguingly, in spite of comparable or higher levels of expression of CRACM2 and CRACM3 homologs, the other defects in mast cell effector functions could not be compensated. Likewise, in SCID patients, a functional defect in CRACM1 deficient T cells could not be compensated by the other two homologs 33. Therefore, even though all three CRACM proteins have been shown to carry store operated CRAC currents in vitro they may be regulated differently and thus function in a non-redundant fashion. Indeed, the three CRACM proteins differ in their inhibition by cytosolic Ca2+ 22, 34. Moreover, the average current amplitudes of CRACM2 and CRACM3 have been shown to be several fold smaller than the corresponding amplitude of CRACM1, in HEK293 over-expression studies 22, 34. These reports were somewhat inconclusive since the differences observed in amplitudes could be due to different expression levels. CRACM1-/- mast cells showing up-regulation of CRACM2 expression still showed small calcium influx and CRAC currents (Fig. 4, 5). These observations combined with a partial block in IL-6 strongly suggest that under physiological conditions, CRACM2 and CRACM3 are capable of forming functional CRAC channels. The small amplitudes suggesting smaller single-channel conductance or open probability for CRACM2 and CRACM3 channels may be sufficient to drive the activation of certain set of transcription factors but not others. Future studies with CRACM2 and CRACM3-/- mice should address these possibilities.

The SCID patients with a point mutation in CRACM1 were reported to have only a rudimentary thymus, although they had normal percentages of T cells in peripheral blood 14. Surprisingly, LacZ staining on newborn CRACM1-/- pups showed no indication of CRACM1 expression in the thymic lymphoid areas (Fig. 7a). In addition, CRACM2 expression in WT thymocytes was found to be much higher compared to CRACM1 and CRACM3 (Fig. 7f). These observations could explain the lack of effect of CRACM1 deletion on T cell development in mice (Fig. 7b). T cells from human SCID patients also proliferated poorly to CD3 or CD3+CD28 stimulation and produced only extremely low levels of most cytokines 14. We, however, did not see a significant reduction in CRACM1-/- T cell proliferation in response to soluble anti-CD3 + anti-CD28 stimulation (Fig. 7c) and while IL-2 and IFN-γ secretion were inhibited, their production was not completely abolished (Fig. 7d, e). There can be many possible explanations for the differences seen in the effect of CRACM1 deletion on human vs mouse T cells including differential CRACM homolog usage between species or interspecies differences in calcium oscillations required for transcription factor activation.

In addition to a defect in T cell effector functions, the human SCID patients showed a non-progressive myopathy 2, 14. Since LacZ staining on CRACM1-/- pups revealed a robust expression for CRACM1 in skeletal muscle cells and in several regions of the brain, these observations suggest a specific and crucial role for CRAC channels in excitable cells. Moreover, as discussed earlier, a number of similarities exist between the process of synaptic vesicle fusion in neurons and exocytosis of SGs in mast cells 23, 28. A crucial role for CRAC channels in skeletal muscles may also explain the smaller size of CRACM1-/- mice (Fig. 1) since we found no obvious abnormality in these mice. In future studies it will be interesting to investigate the physiological roles played by CRAC channels in other tissues such as skeletal muscles brain, heart and kidney.

Methods

Experimental animals

All animals were housed in the Harvard Institute of Medicine (HIM) barrier facility. Studies were conducted in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as well as the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) guidelines of the ARCM, Harvard Medical School.

Generation of CRACM1 deficient mice

A mouse ES cell line (XL922) containing an insertional mutation in CRACM1 was obtained from BayGenomics, a gene-trapping resource. 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) followed by automated DNA sequencing was used to determine the identity of the trapped gene as CRACM1. Male chimeras generated from this ES cell line were bred to B6/D2 females to generate heterozygous CRACM1 mutant (CRACM1+/-) mice. CRACM1+/- mice were intercrossed to produce CRACM1-/- mice.

Southern hybridization

Genomic DNA extracted from tail snips was digested with HindIII and screened using a CRACM1 specific probe, designed 3′ of exon 1.

Derivation of mast cells from embryonic livers

Pregnant CRACM1+/- females from (CRACM1+/- intercrosses) were euthanized with CO2 at day 15pc. Embryos were removed and washed with 1X PBS. Livers extracted from each embryo were teased to obtain single cell suspensions. Cells were differentiated in complete Iscove’s medium containing 20ng/ml each of IL-3 and SCF for 5 wks. At the end of 5 wks and before each assay, cells were stained with anti-FcεRI-α to assess the purity of mast cells.

Degranulation assays

Mast cells were loaded with [3H] 5-hydroxycreatinine ([3H] serotonin; 1 μCi/ 106 cells) and with 0.5μg/ml of DNP-specific IgE in 6-well tissue culture plates (3×106 cells well -1, 37°C, 5% CO2) for 16 hrs. The following day, cells were washed and plated in a 96-well round bottom plates at 105 cells well -1 and incubated at 37°C for 10 min. Triggering of FccRI was performed by the addition of DNP-HSA (final concentration 0, 5, 25 and 50 ng ml-1) and plates were incubated at 37°C for 20 min. Degranulation was stopped by placing the plates on ice for 5 min. 100μl aliquots were taken from triplicate wells and pooled for scintillation counting. Total cellular incorporation was determined from 1% NP-40 lysates.

Leukotriene C4 assays

Leukotriene C4 was measured from 106 anti-DNP IgE-loaded mast cells triggered with 0, 5, 25 or 50 ng ml-1 DNP-HSA. Measurement of LTC4 was done in the supernatants collected 30 min after triggering using LTC4 specific enzyme immunoassay (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI).

TNF-α and IL-6 assays

106 anti-DNP IgE-loaded mast cells were triggered with 0, 5, 25 or 50 ng ml-1 DNP-HSA for 6 hrs. Measurement of TNF-α and IL-6 in the supernatants was performed using specific enzyme immunoassay. Anti-TNF-α and IL-6 coating and detection antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences.

Passive Cutaneous Anaphylaxis in Mice

Mice were anesthetized using avertin and injected intradermally with 25 ng anti-DNP IgE (in left ears) or saline (in right ears). Injection sites were marked on the skin. 24 h after IgE injections animals received 100μl of 1 mg/ml DNP-HSA containing 2% Evan’s blue dye, injected intravenously under anesthesia. 60 min after intravenous injection, mice were killed and their ears were excised. Dye was extracted using formamide and absorbance was measured at 610 nm.

Retroviral reconstitution of CRACM1-/- mast cells

Full length WT-CRACM1 was subcloned into an MSCV-IRES-GFP (MIGW) transfer vector. Retroviruses were created by simultaneously transfecting 293T cells, previously plated in 100mm tissue culture plates, with expression vectors encoding gag/pol, vsv-g env, and CRACM1-IRES-GFP or empty vector, using TransIT 293 transfection reagent (Mirus) according to manufacturers protocol. 24 hours post-transfection, fresh medium was added and cells were subsequently incubated at 32°C. Supernatants were collected every 6 hours starting at 30 hours post-transfection, filtered through .45μm filters and centrifuged at 50000G for 90 minutes at 4°C to pellet virus. Viral pellets were resuspended in 2ml medium containing polybrene and added on mast cells plated in 24 well plates. Plates were subsequently centrifuged at 2500RPM for 90 minutes at room temperature, and incubated overnight at 32°C. The following day, medium was changed and cells cultured as usual for 48 hours prior to use in experiments.

Single Cell Calcium Measurements

Intracellular calcium measurements ([Ca2+]i) were made with primary mast cells loaded with the calcium sensitive fluorescence dye, fura-5F, as described previously (Bird & Putney, Jr., 2005). Briefly, 0.5 ml of mast cell suspensions was plated on 30 mm round coverslips and allowed to attach to the glass for at least 20 mins. Subsequently, the glass coverslip was mounted in a Teflon chamber and cells incubated in DMEM with 1 μM acetoxymethyl ester of fura-5F (Fura- 5F/AM, Molecular Probes, USA) at 37° C in the dark for 25 min. For [Ca2+]i measurements, cells were bathed in HEPES-buffered salt solution (HBSS: NaCl 120; KCl 5.4; Mg2SO4 0.8; HEPES 20; CaCl2 1.0 and glucose 10 mM, with pH 7.4 adjusted by NaOH) at room temperature. Nominally Ca2+-free solutions were HBSS with no added CaCl2. Fluorescence images of the cells were recorded and analyzed with a digital fluorescence imaging system (InCyt Im2, Intracellular Imaging Inc., Cincinnati, OH). Fura-5F fluorescence was monitored by alternatively exciting the dye at 340 and 380 nm, and collecting the emission wavelength at 520 nm. Changes in intracellular calcium are expressed as the “Ratio” (in figures) of fura-5F fluorescence due to excitation at 340 nm and 380 nm (F340/F380). Before starting the experiment, regions of interests identifying single cells were created, with typically 25 to 50 cells were monitored per experiment. In all cases, ratio values have been corrected for contributions by autofluorescence, which is measured after treating cells with 10 μM ionomycin and 20 mM MnCl2. During each experiment, mast cells were exposed to test solutions by exchanging the bathing solution.

Electrophysiology

Store-operated currents were investigated in primary mast cells using the patch-clamp technique in the whole-cell configuration. All experiments were performed at room temperature (20-25°C). The standard HEPES buffered saline solution (HBSS) contained (mM): 145 NaCl, 3 KCl, 10 CsCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 10-20 CaCl2, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES (pH to 7.4 with NaOH). The standard divalent free (DVF) solution contained (in mM): 155 Na-methanesulfonate, 10 HEDTA, 1 EDTA and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4). Fire-polished pipets fabricated from borosilicate glass capillaries (WPI, Sarasota, FL) with 3-4 MΩ resistance were filled with (in mM): 145 Cs-methanesulfonate, 20 BAPTA, 10 HEPES, and 8 MgCl2 (pH to 7.2 with CsOH). Intracellular calcium pools were depleted either passively (BAPTA alone), or actively (BAPTA + IP3) with 20 μM inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3, Sigma, St. Louis) added to the pipet solution. Voltage ramps (-100 mV to +100 mV) of 250 ms were recorded every two seconds immediately after gaining access to the cell from a holding potential of 0 mV, and currents were normalized based on cell capacitance. Access resistance was typically between 5-10 MΩ. The currents were acquired with pCLAMP-10 (Axon Instruments) and analyzed with Clampfit (Axon Instruments) and Origin 6 (Microcal) software. All solutions were applied by means of a gravity based multi-barrel focal perfusion system with a low dead volume common delivery port (Perfusion pencil, Automate Scientific, Inc).

LacZ staining

Newborn pups were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed and frozen in OCT medium on dry-ice. Frozen tissue was cryo-sectioned at 20μm thickness, sections were fixed with 0.25% glutaraldehyde, washed and stained O/N with LacZ staining solution at 37°C and observed using a light microscope.

Isolation of RNA and quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cells by RNA-Bee (Tel-Test, Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 1μg of total RNA and oligo-dT primers were used to generate cDNA using Superscript III kit (Invitrogen). For quantitative PCR, 125ng of cDNA was used per reaction. Reactions were performed using TaqMan Gene Expression PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosytems Inc.) and commercially prepared primers and probes for murine CRACM1, CRACM2 and CRACM3 (Mm00774349.m1, Mm01207170.m1, Mm01612886.m1, Applied Biosystems) as recommended by the manufacturer. Reactions were run on a BioRad iCycler for 40 cycles.

T cell proliferation and cytokine assays

Spleen cell suspensions were plated at 2X 105 cells/well and stimulated with titrating doses (0.01 to 0.3ug/ml) of soluble anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 in 96-well flat bottom plates for 48 hrs. Proliferation was measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation for the last 6 hrs. For estimation of cytokines, 100ul supernatants were collected from replicate 96-well plates. Triplicate samples were pooled and diluted 1:2 in PBS. Cytokine concentrations were determined using the BioPlex mouse 23plex bead array assay (BioRad) according to manufacturer specifications.

Antibodies and flow cytometry

CD4-PE-Cy5 and CD8-FITC were purchased from BD Biosciences. For cytofluorimetric analyses, single-cell suspensions were prepared from thymus and spleen, and stained with directly conjugated monoclonal antibodies in 2% FBS in PBS. Data were acquired with a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson) in conjunction with CellQuest software and analyzed with the FlowJo program (TreeStar).

Acknowledgements

We thank Adish Dani for stimulating discussions and help with LacZ staining and analysis, Murielle-Koblan Huberson for help with genotyping, Dr. Beverly Koller for help with the generation and analysis of CRACM1-/- mice. This work was supported by the NIH (GM 053950) grant to JP and the Irvington Institute Fellowship to MV and in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

References

- 1.Vig M, et al. CRACM1 is a plasma membrane protein essential for storeoperated Ca2+ entry. Science. 2006;312:1220–1223. doi: 10.1126/science.1127883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feske S, et al. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature. 2006;441:179–185. doi: 10.1038/nature04702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang SL, et al. Genome-wide RNAi screen of Ca(2+) influx identifies genes that regulate Ca(2+) release-activated Ca(2+) channel activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9357–9362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603161103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vig M, et al. CRACM1 Multimers Form the Ion-Selective Pore of the CRAC Channel. Curr Biol. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeromin AV, et al. Molecular identification of the CRAC channel by altered ion selectivity in a mutant of Orai. Nature. 2006;443:226–229. doi: 10.1038/nature05108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prakriya M, et al. Orai1 is an essential pore subunit of the CRAC channel. Nature. 2006;443:230–233. doi: 10.1038/nature05122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoth M, Penner R. Depletion of intracellular calcium stores activates a calcium current in mast cells. Nature. 1992;355:353–356. doi: 10.1038/355353a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parekh AB, Putney JW., Jr. Store-operated calcium channels. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:757–810. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00057.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turner H, Kinet JP. Signalling through the high-affinity IgE receptor Fc epsilonRI. Nature. 1999;402:B24–30. doi: 10.1038/35037021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parravicini V, et al. Fyn kinase initiates complementary signals required for IgEdependent mast cell degranulation. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:741–748. doi: 10.1038/ni817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nadler MJ, Kinet JP. Uncovering new complexities in mast cell signaling. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:707–708. doi: 10.1038/ni0802-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kraft S, Kinet JP. New developments in FcepsilonRI regulation, function and inhibition. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:365–378. doi: 10.1038/nri2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chapman ER. Synaptotagmin: a Ca(2+) sensor that triggers exocytosis? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:498–508. doi: 10.1038/nrm855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feske S, et al. Severe combined immunodeficiency due to defective binding of the nuclear factor of activated T cells in T lymphocytes of two male siblings. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:2119–2126. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skarnes WC. Gene trapping methods for the identification and functional analysis of cell surface proteins in mice. Methods Enzymol. 2000;328:592–615. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)28420-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawakami T, Galli SJ. Regulation of mast-cell and basophil function and survival by IgE. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:773–786. doi: 10.1038/nri914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morgan AJ, Jacob R. Ionomycin enhances Ca2+ influx by stimulating store-regulated cation entry and not by a direct action at the plasma membrane. Biochem J. 1994;300(Pt 3):665–672. doi: 10.1042/bj3000665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein M, et al. Specific and redundant roles for NFAT transcription factors in the expression of mast cell-derived cytokines. J Immunol. 2006;177:6667–6674. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalesnikoff J, et al. SHIP negatively regulates IgE + antigen-induced IL-6 production in mast cells by inhibiting NF-kappa B activity. J Immunol. 2002;168:4737–4746. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wershil BK, Mekori YA, Murakami T, Galli SJ. 125I-fibrin deposition in IgE-dependent immediate hypersensitivity reactions in mouse skin. Demonstration of the role of mast cells using genetically mast cell-deficient mice locally reconstituted with cultured mast cells. J Immunol. 1987;139:2605–2614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleming TJ, et al. Negative regulation of Fc epsilon RI-mediated degranulation by CD81. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1307–1314. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeHaven WI, Smyth JT, Boyles RR, Putney JW., Jr. Calcium inhibition and calcium potentiation of Orai1, Orai2, and Orai3 calcium release-activated calcium channels. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:17548–17556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611374200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blank U, Rivera J. The ins and outs of IgE-dependent mast-cell exocytosis. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Penner R, Neher E. Secretory responses of rat peritoneal mast cells to high intracellular calcium. FEBS Lett. 1988;226:307–313. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)81445-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Penner R, Matthews G, Neher E. Regulation of calcium influx by second messengers in rat mast cells. Nature. 1988;334:499–504. doi: 10.1038/334499a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rettig J, Neher E. Emerging roles of presynaptic proteins in Ca++-triggered exocytosis. Science. 2002;298:781–785. doi: 10.1126/science.1075375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weber T, et al. SNAREpins: minimal machinery for membrane fusion. Cell. 1998;92:759–772. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81404-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martens S, Kozlov MM, McMahon HT. How synaptotagmin promotes membrane fusion. Science. 2007;316:1205–1208. doi: 10.1126/science.1142614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Serfling E, et al. The role of NF-AT transcription factors in T cell activation and differentiation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1498:1–18. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(00)00082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Macian F. NFAT proteins: key regulators of T-cell development and function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:472–484. doi: 10.1038/nri1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis RS. Calcium oscillations in T-cells: mechanisms and consequences for gene expression. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:925–929. doi: 10.1042/bst0310925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gonzalez-Espinosa C, et al. Preferential signaling and induction of allergy-promoting lymphokines upon weak stimulation of the high affinity IgE receptor on mast cells. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1453–1465. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gwack Y, et al. Biochemical and functional characterization of Orai proteins. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:16232–16243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609630200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lis A, et al. CRACM1, CRACM2, and CRACM3 are store-operated Ca2+ channels with distinct functional properties. Curr Biol. 2007;17:794–800. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]