Abstract

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is thought to be a necessary but not sufficient cause of most cases of cervical cancer. Since oral contraceptive use for long durations is associated with an increased risk of cervical cancer, it is important to know whether HPV infection is more common in oral contraceptive users. We present a systematic review of 19 epidemiological studies of the risk of genital HPV infection and oral contraceptive use. There was no evidence for a strong positive or negative association between HPV positivity and ever use or long duration use of oral contraceptives. The limited data available, the presence of heterogeneity between studies and the possibility of bias and confounding mean, however, that these results must be interpreted cautiously. Further studies are needed to confirm these findings and to investigate possible relations between oral contraceptive use and the persistence and detectability of cervical HPV infection.

Keywords: human papillomavirus, oral contraceptives, cervix cancer

Infection with certain ‘high-risk’ types of the human papillomavirus (HPV) is thought to be a necessary but not sufficient cause of most cases of cervical cancer (IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, 1999; Walboomers et al, 1999). In recent analyses of data from case–control and cohort studies, an increased risk of cervical cancer with increasing duration of oral contraceptive use was confirmed both in all women and in HPV positive women (Moreno et al, 2002; Smith et al, 2003). This suggests that long duration use of oral contraceptive may influence the development of cervical cancer in women infected with HPV, however in interpreting these results it is important to know whether such use of oral contraceptives is itself associated with HPV infection. We have reviewed available evidence from epidemiological studies on any relation between the use of oral contraceptives and genital HPV infection.

METHODS

Studies were identified through a search of MEDLINE (1966–August 2002) using the search terms ‘papillomavirus’, search restricted to human studies (pre-1994) or ‘papillomavirus, human’ (1994–2002) and ‘risk factors’, and supplemented by references from identified studies. Two studies then in press (Anh et al, 2003; Shin et al, 2003) were obtained from groups reporting relevant data at the International Papillomavirus Conferences, 2000–2002. Studies were eligible for inclusion in this review if they had: (i) at least 200 subjects with normal cervical cytology or from a population with ‘mixed’ normal and abnormal cytology but at relatively low risk for cytological abnormality, such as general population surveys or routine screening or gynaecological clinics (studies of women attending colposcopy clinics or with conditions such as HIV infection, likely to be associated with a substantially increased risk of cervical abnormality, were excluded); (ii) any measure of genital HPV infection as the outcome; (iii) information on oral contraceptive use; and (iv) relative risk estimated for HPV positivity in oral contraceptive users vs never users either adjusted for age, or calculated for age-matched or age-restricted subjects. The most adjusted relative risk available was used for analysis. No restriction was placed on the language of publication. The term ‘HPV positivity’ is used to reflect the fact that what is measured by the various tests for HPV is detectable HPV rather than, necessarily, underlying HPV infection. ‘High-risk’ (oncogenic) and ‘low-risk’ (nononcogenic) HPV types were as defined in each eligible study; all studies included types 16 and 18 in high-risk and types 6 and 11 in low-risk groups, but studies varied with regard to the number and classification of other types.

In most studies, the term ‘oral contraceptive’ was used irrespective of the dose or formulation of contraceptive pills and it was not possible to distinguish in these studies between the use of combined or progestogen-only pills. It is likely, however, that the large majority of oral contraceptive users had used preparations containing combined oestrogen and progestogen (Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer, 1996; IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, 1999).

For analysing the effect of duration of oral contraceptive use, results were grouped as ‘short duration’ (less than 5 years use), ‘medium duration’ (5–9 years use), and ‘long duration’ (10 or more years use), with published results allocated to the most appropriate group. For studies that had more than one data point within a duration category, data were combined using the method of generalised least squares taking into account the correlations between the relative risks being combined (Berrington and Cox, in press). In this analysis, current use of oral contraceptives is use described as ‘current’ or use within the past 12 months and past use is use described as ‘past’ or use that ceased more than 12 months in the past.

The results are summarised graphically in the figures, which show relative risks for HPV positivity in users of oral contraceptives compared with never users. Studies are listed in order of date of publication, earliest first. Black squares indicate relative risks, the area of each square being proportional to the amount of statistical information contributed, with horizontal lines indicating 95% confidence intervals. The method of empirically weighted least squares (Cox and Snell, 1989) was used to test for heterogeneity between relative risks.

RESULTS

Overall, 19 eligible studies were identified, with data on HPV status and oral contraceptive use for a total of 20 509 women (Kjaer et al, 1990, 1997; Ley et al, 1991; Karlsson et al, 1995; Burk et al, 1996; Kotloff et al, 1998; Giuliano et al, 1999, 2001, 2002; Deacon et al, 2000; Richardson et al, 2000; Rousseau et al, 2000; Sellors et al, 2000; Lazcano-Ponce et al, 2001; Peyton et al, 2001; Berrington et al, 2002; Molano et al, 2002; Moreno et al, 2002; Anh et al, 2003; Shin et al, 2003). Details of the studies are given in Table 1 . The study by Moreno et al (2002) provided a pooled analysis of data on control subjects from eight case–control studies of cervical cancer. In two other studies, the subjects were also controls from case–control studies of cervical cancer (Deacon et al, 2000; Berrington et al, 2002). All studies measured prevalent HPV positivity, that is, the numbers of women testing positive at one point in time, with no distinction between recent and persistent infection; in the study by Rousseau et al (2000), women becoming HPV positive within the 12 months of study follow-up were also classed as HPV positive. In four studies (Kjaer et al, 1997; Lazcano-Ponce et al, 2001; Molano et al, 2002; Moreno et al, 2002), all subjects had normal cervical cytology; in the other studies, the proportion of women with normal cytology ranged from 89 to 99%. In all but one study, HPV DNA was detected in cervical specimens by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based (15 studies) or hybridisation methods; in the study by Berrington et al (2002) and in part of the study by Shin et al (2003), high-risk (genital) HPV types were detected by serology.

Table 1. Epidemiological studies eligible for this review of the relation between human papillomavirus (HPV) positivity and use of oral contraceptives (oral contraceptives).

| Study | Country | Year | Design | Number of subjects with HPV and oral contraceptive data | Cytology | HPV measure | HPV type | % HPV positive in study |

RR adjusted fora |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual partners | Other | |||||||||

| Kjaer et al (1990) | Denmark, Greenland | 1986 | C/s population | 1114 | Mixed | FISH | Any | 14 | Yes | Area, cytology, age at first oral contraceptive use |

| High risk: 16,18 | 12 | Yes | Area, cytology | |||||||

| Low risk: 6,11 | 7 | Yes | Area, parity | |||||||

| Ley et al (1991) | USA | 1989 | C/s college | 467 | Mixed | PCR MY09/11 | Any | 46 | Yes | Race |

| Karlsson et al (1995) | Sweden | 1989 | C/s population | 526 | Mixed | PCR MY09/11, GP5/6 | Any | 22 | No | — |

| Burk et al (1996) | USA | 1992–94 | C/s college | 602 | Mixed | PCR MY09/11,Southern blot | Any | 28 | No | — |

| Kjaer et al (1997) | Denmark | 1991–93 | C/s population | 956 | Normal | PCR GP5/6 | Any | 15115 | Yes | Parity, condom use |

| High risk: 16, 18+ | Yes | Chlamydia | ||||||||

| Low risk: 6,11,uc | Yes | |||||||||

| Kotloff et al (1998) | USA | 1992–93 | C/s college | 414 | Mixed | PCR MY09/11 | Any | 35 | Yes | Race, condom use, parity, smoking, STDs, age at first intercourse |

| Giuliano et al (1999) | USA | 1992–95 | C/s clinic | 971 | Mixed | HC | High risk: 16,18+ | 13 | Yes | Place of birth, marital status |

| Deacon et al (2000) | UK | 1987–93 | C/s controlsb | 384 | Mixed | PCR MY09/11 | Any | 47 | No | — |

| Richardson (2000) | Canada | 1992–93 | C/s college | 375 | Mixed | PCR MY09/11 | Any | 23 | No | — |

| High risk: 16, 18+ | 12 | |||||||||

| Low risk: 6,11+,uc | 13 | |||||||||

| Rousseau et al (2000) | Brazil | 1993+ | Cumulative c/c | 765 | Mixed | PCR MY09/11 | High risk: 16, 18+ | N/a | No - | |

| Low risk: 6, 11+, uc | N/a | |||||||||

| Sellors et al (2000) | Canada | 1998–99 | C/s clinic | 954 | Mixed | HC ll | High risk: 16, 18+ | 13 | Yes | Marital status, smoking |

| Giuliano et al (2001,2002) | USA/Mexico | 1997–98 | C/s clinic | 2031 | Mixed | PCR MY09/11 | Any | 14 | No | — |

| High risk: 16, 18+ | 12 | |||||||||

| Low risk: 6,11+ | 3 | |||||||||

| Lazcano-Ponce et al (2001) | Mexico | 1996–99 | C/s population | 1340 | Normal | PCR L1 | Any | 13 | Yes | Marital status, parity, age at first intercourse, socioeconomic status |

| High risk: 16, 18+ | 10 | |||||||||

| Low risk: 6,11+ | 3 | |||||||||

| Peyton et al (2001) | USA | 1996–2000 | C/s clinic | 3671 | Mixed | PCR MY09/11 | Any | 39 | Yes | Race, education, income, marital status, parity, diaphragm use, STDs |

| High risk: 16, 18+ | 27 | |||||||||

| Low risk: 6,11+ | 15 | |||||||||

| Berrington et al (2002) | UK | 1984–91 | C/s controlsb | 393 | Mixed | Serology for E7 proteins | High risk: 16,18 | 11 | Yes | Smoking |

| Molano et al (2002) | Colombia | 1993–95 | C/s population/clinic | 1845 | Normal | PCR GP5+/6+ | Any | 15 | Yes | Education, parity, condom use, smoking, age at first intercourse |

| High risk: 16, 18+ | 11 | |||||||||

| Low risk: 6, 11+ | 3 | |||||||||

| Molano et al (2002) | Multicentre | 1985–97 | C/s controlsb | 1916 | Normal | PCR MY09/11,GP5+/6+ | Any | 13 | No | Centre |

| High risk: 16, 18+ | 8 | |||||||||

| Low risk: 6, 11+ | 5 | |||||||||

| Anh et al (in press) | Vietnam (Ho Chi Minh) | 1997 | C/s clinic | 922 | Mixed | PCR GP5+/6+ | Any | 11 | Yes | Education, smoking, parity, abortion, HSV |

| Shin et al (in press) | Korea | 1999–2000 | C/s population | 863 | Mixed | PCR GP5+/6+Serology for VLPs | Any | 10 | No | — |

| High risk: 16, 18+ | 20 | |||||||||

OC=oral contraceptive; RR=relative risk; C/s=cross-sectional study; c/c=case–control study; population=general population; clinic=family planning or general gynaecological clinic; FISH=filter in situ hybridisation; HC=hybrid capture; VLP=virus-like particle; N/a=not applicable; STD=sexually transmitted disease; HSV=herpes simplex virus. HPV types: 16, 18=types 16 and 18 only; 16,18+=16,18 and other high-risk types; 6,11=types 6 and 11 only; 6,11+=6,11 and other low-risk types; uc=uncharacterised types.

All RR adjusted for age, or based on age-restricted subjects. Not all analyses adjusted for all variables shown.

These studies use control women from case–control studies of cervical cancer as their subjects.

The following analyses are based on the data presented in published reports for the duration of use of oral contraceptives and for ever, current and past use. In many studies, the information provided was insufficient to allow inclusion of the study in all analyses.

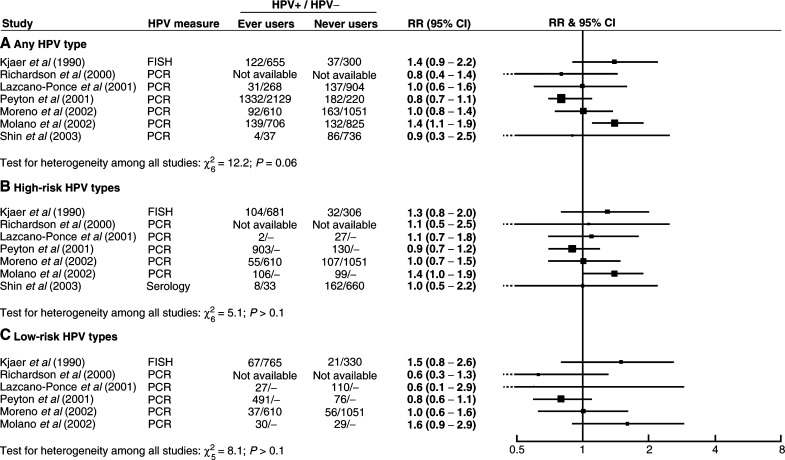

Figure 1 shows the relation between HPV positivity and ever use of oral contraceptives in the seven studies that presented these results. Results are shown for any HPV type, and separately for high-risk and low-risk HPV types. There was considerable variation between studies in the relative risks for HPV positivity in ever users vs never users of oral contraceptives, and no evidence for a strong positive or negative effect overall. Summary relative risks for ever vs never use have not been calculated as we do not feel that they would adequately reflect the variability in results between studies. The results of a statistical test for heterogeneity are included in this and subsequent figures for information; it should be borne in mind that such tests generally have a low sensitivity (Greenland, 1987) and should not be used as the sole criterion of important heterogeneity between studies.

Figure 1.

Relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for (A) any type, (B) high-risk and (C) low-risk HPV positivity in ever users vs never users of oral contraceptives.

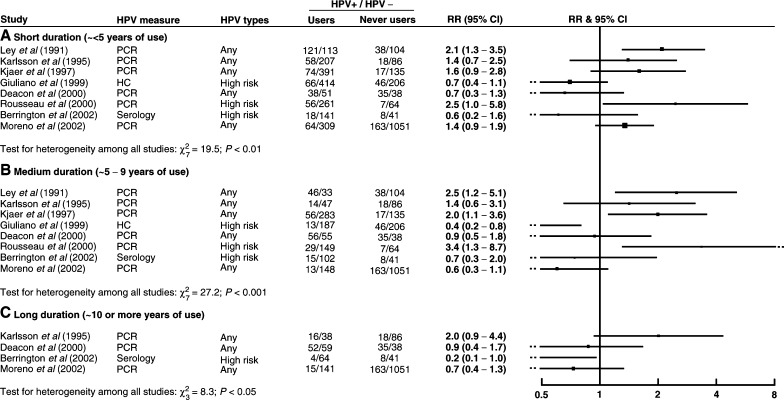

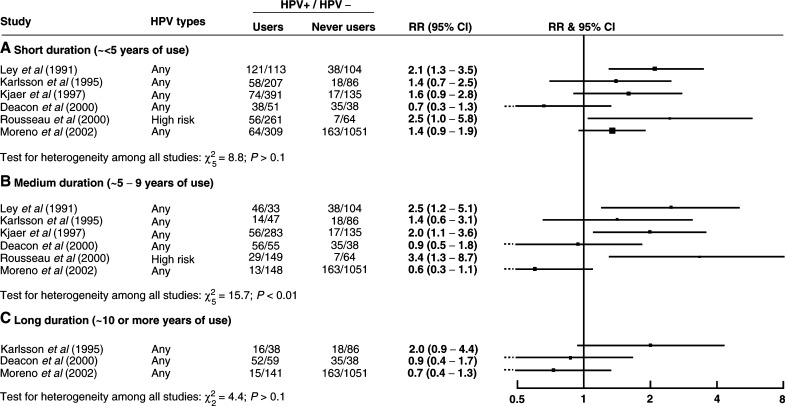

Information on duration of use was available from eight studies, of which only four included long duration. There was no clear evidence for an effect of duration of oral contraceptive use on the risk of HPV positivity (Figure 2). There was no consistency between studies in apparent trend of HPV positivity with duration of use, with individual studies showing increased, decreased or unchanged risk of HPV positivity with increasing duration of oral contraceptive use. The lack of information on long duration use and the variability between study results mean that, again, calculation of summary relative risks would not be appropriate.

Figure 2.

Relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for HPV positivity for (A) short-, (B) medium- and (C) long-duration users vs never users of oral contraceptives.

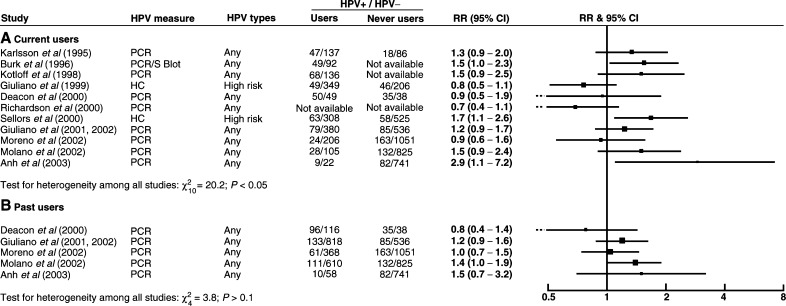

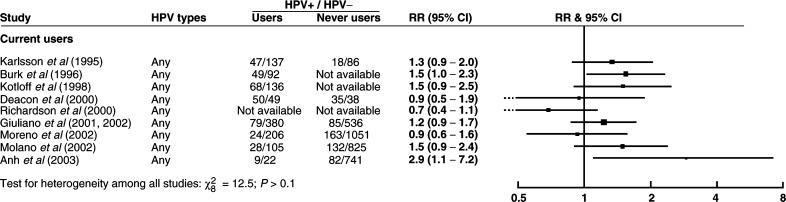

Relative risks for HPV positivity in relation to current and past use of oral contraceptives are shown in Figure 3. Again there was considerable variability between study results and no clear evidence for a strong positive or negative association between oral contraceptive use and HPV positivity.

Figure 3.

Relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for HPV positivity in (A) current and (B) past users vs never users of oral contraceptives.

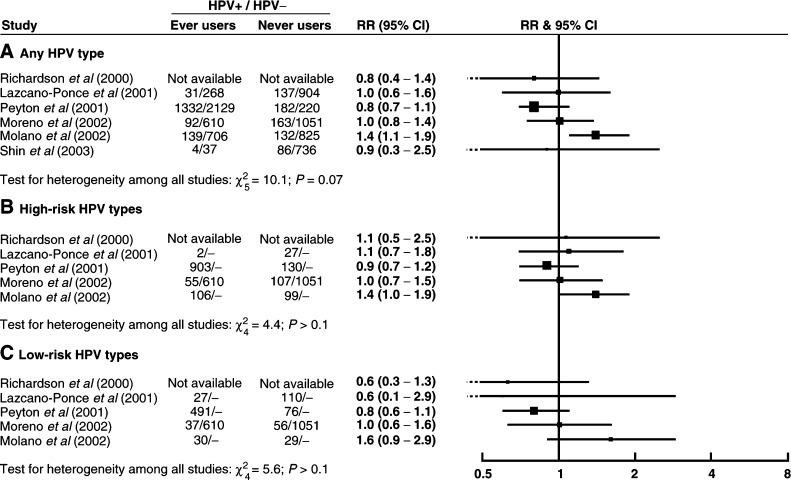

Lack of information severely limited attempts to investigate possible sources of heterogeneity within this analysis. Figures 4, 5 and 6 show the results for ever use, duration of use and current use in the 15 studies that used PCR methods to detect HPV (all of the studies with data on past use had used PCR). There were no obvious differences in the results of this analysis compared to the results of the analysis of all 19 studies, although restriction to PCR-based studies was associated with some reduction in statistical heterogeneity between studies. There were too few studies using non-PCR measures of HPV positivity to allow a direct comparison of PCR and non-PCR studies. The results from 10 of the 19 studies had been adjusted for the lifetime number of sexual partners. Restriction to these studies did not materially alter the findings of this review, and there remained considerable variability between studies. The number of studies available for each analysis was, however, very limited (four studies with information on ever use of oral contraceptives; four with information on short and medium duration of use but only one with information on long duration use; five with information on current and two with information on past use). Lack of information meant that it was not possible to attempt to assess the importance of the type of population (normal or mixed cytology) or of adjustment for factors such as socioeconomic status, smoking and reproductive factors.

Figure 4.

Relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for (A) for any type, (B) high-risk and (C) low-risk HPV positivity in ever users vs never users of oral contraceptives, restricted to PCR studies.

Figure 5.

Relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for HPV positivity for (A) short-, (B) medium- and (C) long-duration users vs never users of oral contraceptives, restricted to PCR studies.

Figure 6.

Relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for HPV positivity in current users vs never users of oral contraceptives, restricted to PCR studies.

DISCUSSION

We found no evidence from available data for a strong positive or negative association between the use of oral contraceptives and the simultaneous or later detection of HPV on the cervix. In particular, there was no clear evidence for an effect of duration of oral contraceptive use on HPV positivity.

The present results must, however, be interpreted with caution. Limited information was available for many of the analyses, and there was considerable heterogeneity in study design and in results. There are also a number of potentially important sources of bias and confounding within the available data.

The prevalence of cervical HPV positivity is strongly related to age, with younger women having a higher prevalence, especially of high-risk HPV types (Melkert et al, 1993; Jacobs et al, 2000; Chan et al, 2002); and so is oral contraceptive use. Although this review has included only results adjusted for age (or, in two studies, restricted to women within a narrow age range), the degree of adjustment in most studies was probably insufficient to account fully for potential confounding. Most studies used 5–10 year age bands for adjustment and there is evidence that HPV prevalence may vary widely within such bands (Ley et al, 1991; Melkert et al, 1993). Residual confounding by age is particularly important in the analyses of the effects of duration of use of oral contraceptives, as short-duration users will tend to be younger than long-duration users.

Sexual activity is an important potential confounding factor in the studies considered here. The number of male sexual partners, in particular, is a major risk factor for cervical HPV infection (IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, 1995) and oral contraceptive use is related to sexual behaviour (Swan and Brown, 1981; Svare et al, 1997), although it seems likely that the nature of this relation varies substantially with age, time and place (Oddens and Lehert, 1997; Spinelli et al, 2000). We found no obvious difference in results between studies with adjustment for the lifetime number of sexual partners and those without in this review, but the information available was insufficient to address this question fully.

The relation between duration of oral contraceptive use and HPV positivity may be critical in understanding the epidemiological and aetiological relations between oral contraceptives and HPV infection. Related to this is the question of the possible effects of oral contraceptive use on the persistence and detectability of HPV infection. The studies reviewed here provide very limited information on long duration of oral contraceptive use, and (with one exception) deal only with prevalent HPV positivity measured at varying times in relation to oral contraceptive use. Insufficient information was available to allow investigation of possible differences between the risks for high-risk and low-risk HPV positivity in the analyses of duration of use or of current or past use of oral contraceptives, although patterns of infection may differ between high-risk and low-risk HPV types (Elfgren et al, 2000; Jacobs et al, 2000).

For completeness, we have included in this review studies using different methods of detection of HPV. Differences in sensitivity and specificity between PCR-based and non-PCR-based tests could introduce bias as misclassification of subjects as HPV positive or negative will tend to attenuate a true association between a risk factor and HPV status. In this review, restriction to PCR-based studies did not materially alter the results. Differential misclassification, in which the sensitivity or specificity of an HPV test is itself related to the risk factor being studied, in this case to oral contraceptive use, remains a possible source of bias within studies using any method of HPV detection.

In evaluating the relation between oral contraceptive use and HPV infection, it may be appropriate to include, where possible, studies using different methods of HPV detection as these may reflect different aspects of HPV infection. Serological studies are thought to measure cumulative lifetime exposure to HPV (although it is not clear to what extent persistence of infection is reflected in antibody response), whereas measures of cervical HPV DNA are likely to reflect current and persistent past infection (Shin et al, 2003). Non-PCR methods of detecting HPV DNA may preferentially detect infections of high viral load and these may be of particular clinical significance (Ylitalo et al, 2000; Lorincz et al, 2002).

The relation between oral contraceptive use and the use of barrier methods of contraception is a potential source of confounding, and it has not been possible to address this here. In some populations, nonusers of oral contraceptives are likely to use barrier methods, and as many as a third of young oral contraceptive users in some recent studies report also using condoms (Peipert et al, 1997; Svare et al, 1997). Since barrier contraceptives may reduce the risk of HPV transmission (Manhart and Koutsky, 2002), such associations may be important.

Most eligible studies included some women with cytological abnormalities; while the number of women with severe grades of cytological abnormality (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 3, high-grade squamous cell intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) or above) was very small (typically about 1%), the strong association between cervical cancer and HPV means that they accounted for up to 10% of the HPV-positive women in these studies. This seems unlikely to prove a significant source of bias in the measured relation between oral contraceptive use and HPV. Low-grade cytological abnormalities (CIN1/2, LSIL), which may be present in up to 10% of women in these unselected populations, and which may account for a further 10% of HPV positives in these populations, may simply indicate HPV infection and should probably not be considered a possible source of bias.

There are a number of hypotheses but little direct evidence about the ways in which oral contraceptives might influence cervical HPV infection. The use of oral contraceptives is associated with an increased incidence of cervical ectropion, which means that the site where HPV infection preferentially induces neoplastic lesions, the squamo-columnar junction, is more exposed to potential carcinogens. Oestrogen and progestogens may also affect cervical cells directly, increasing cell proliferation and stimulating transcription of HPVs (de Villiers, 2003). Oral contraceptives might thus affect not only viral infection and malignant transformation of cervical cells but also the sensitivity or specificity of tests for detecting HPV infection.

In conclusion, this review provides preliminary evidence suggesting that there is no strong positive or negative relation between oral contraceptive use and prevalent infection of the cervix with HPV. Given that HPV infection appears to be a necessary cause of most cases of cervical cancer, this finding, if true, is of considerable importance as it suggests that HPV status is not likely to confound examination of the relation between long duration use of oral contraceptives and the risk of cervical cancer. However, there are serious problems in interpreting these results and further evidence is needed to address the methodological and other issues raised.

References

- Anh P, Hieu N, Herrero R, Vaccarella S, Smith JS, Thuy N, Nga N, Duc N, Ashley R, Snijders P, Meijer C, Munoz N, Parkin DM, Franceschi S (2003) Human papillomavirus infection among women in South and North Vietnam. Int J Cancer 104: 213–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrington A, Cox DR (in press) Generalised least squares for the synthesis of correlated information. Biostatistics [DOI] [PubMed]

- Berrington A, Jha PK, Peto J, Green J, Hermon C (2002) Oral contraceptives and cervical cancer (letter). Lancet 360: 410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burk RD, Ho GY, Beardsley L, Lempa M, Peters M, Bierman R (1996) Sexual behavior and partner characteristics are the predominant risk factors for genital human papillomavirus infection in young women. J Infect Dis 174: 679–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan PK, Chang AR, Cheung JL, Chan DP, Xu LY, Tang NL, Cheng AF (2002) Determinants of cervical human papillomavirus infection: differences between high- and low-oncogenic risk types. J Infect Dis 185: 28–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer (1996) Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: further results. Contraception 54: 1S–106S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR, Snell EJ (1989) Analysis of Binary Data. London: Chapman & Hall [Google Scholar]

- de Villiers E-M (2003) Relationship between steroid hormone contraceptives and HPV, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical carcinoma. Int J Cancer 103: 705–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deacon J, Evans CD, Yule R, Desai M, Binns W, Taylor C, Peto J (2000) Sexual behaviour and smoking as determinants of cervical HPV infection and of CIN3 among those infected: a case–control study nested within the Manchester cohort. Br J Cancer 83: 1565–1572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elfgren K, Kalantari M, Moberger B, Hagmar B, Dillner J (2000) A population-based five-year follow-up study of cervical human papillomavirus infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol 183: 561–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano AR, Papenfuss M, Abrahamsen M, Denman C, de Zapien JG, Henze JL, Ortega L, Brown GE, Stephan J, Feng J, Baldwin S, Garcia F, Hatch K (2001) Human papillomavirus infection at the United States–Mexico border: implications for cervical cancer prevention and control. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 10: 1129–1136 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano AR, Papenfuss M, Abrahamsen M, Inserra P (2002) Differences in factors associated with oncogenic and nononcogenic human papillomavirus infection at the United States–Mexico border. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 11: 930–934 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano AR, Papenfuss M, Schneider A, Nour M, Hatch K (1999) Risk factors for high-risk type human papillomavirus infection among Mexican-American women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 8: 615–620 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S (1987) Quantitative methods in the review of epidemiologic literature. Epidemiol Rev 9: 1–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans (1995) Human papillomaviruses. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Vol. 64, pp 1–409 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans (1999) Hormonal contraception and post-menopausal hormonal therapy. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Vol. 72, pp 49–6610533177 [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs MV, Walboomers JM, Snijders PJ, Voorhorst FJ, Verheijen RH, Fransen-Daalmeijer N, Meijer CJ (2000) Distribution of 37 mucosotropic HPV types in women with cytologically normal cervical smears: the age-related patterns for high-risk and low-risk types. Int J Cancer 87: 221–227 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson R, Jonsson M, Edlund K, Evander M, Gustavsson A, Boden E, Rylander E, Wadell G (1995) Lifetime number of partners as the only independent risk factor for human papillomavirus infection: a population-based study. Sex Transm Dis 22: 119–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjaer SK, Engholm G, Teisen C, Haugaard BJ, Lynge E, Christensen RB, Moller KA, Jensen H, Poll P, Vestergaard BF (1990) Risk factors for cervical human papillomavirus and herpes simplex virus infections in Greenland and Denmark: a population-based study. Am J Epidemiol 131: 669–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjaer SK, van den Brule AJ, Bock JE, Poll PA, Engholm G, Sherman ME, Walboomers JM, Meijer CJ (1997) Determinants for genital human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in 1000 randomly chosen young Danish women with normal Pap smear: are there different risk profiles for oncogenic and nononcogenic HPV types? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 6: 799–805 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotloff KL, Wasserman SS, Russ K, Shapiro S, Daniel R, Brown W, Frost A, Tabara SO, Shah K (1998) Detection of genital human papillomavirus and associated cytological abnormalities among college women. Sex Transm Dis 25: 243–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazcano-Ponce E, Herrero R, Munoz N, Cruz A, Shah KV, Alonso P, Hernandez P, Salmeron J, Hernandez M (2001) Epidemiology of HPV infection among Mexican women with normal cervical cytology. Int J Cancer 91: 412–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley C, Bauer HM, Reingold A, Schiffman MH, Chambers JC, Tashiro CJ, Manos MM (1991) Determinants of genital human papillomavirus infection in young women. J Natl Cancer Inst 83: 997–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorincz A, Castle P, Sherman ME, Scott DR, Glass AG, Wacholder S, Rush BB, Gravitt P, Schussler J, Schiffman M (2002) Viral load of human papillomavirus and risk of CIN3 or cervical cancer. Lancet 360: 228–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manhart LE, Koutsky LA (2002) Do condoms prevent genital HPV infection, external genital warts, or cervical neoplasia? A meta-analysis. Sex Transm Dis 29: 725–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melkert PW, Hopman E, van den Brule AJ, Risse EK, van Diest PJ, Bleker OP, Helmerhorst T, Schipper ME, Meijer CJ, Walboomers JM (1993) Prevalence of HPV in cytomorphologically normal cervical smears, as determined by the polymerase chain reaction, is age-dependent. Int J Cancer 53: 919–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molano M, Posso H, Weiderpass E, van den Brule AJC, Ronderos M, Franceschi S, Meijer CJ, Arslan A, Munoz N, HPV Study Group (2002) Prevalence and determinants of HPV infection among Colombian women with normal cytology. Br J Cancer 87: 324–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno V, Bosch FX, Munoz N, Meijer CJ, Shah KV, Walboomers JM, Herrero R, Franceschi S (2002) Effect of oral contraceptives on risk of cervical cancer in women with human papillomavirus infection: the IARC multicentric case–control study. Lancet 359: 1085–1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddens BJ, Lehert P (1997) Determinants of contraceptive use among women of reproductive age in Great Britain and Germany. I: demographic factors. J Biosoc Sci 29: 415–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peipert JF, Domagalski L, Boardman L, Daamen M, McCormack WM, Zinner SH (1997) Sexual behavior and contraceptive use. Changes from 1975 to 1995 in college women. J Reprod Med 42: 651–657 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyton CL, Gravitt PE, Hunt WC, Hundley RS, Zhao M, Apple RJ, Wheeler CM (2001) Determinants of genital human papillomavirus detection in a US population. J Infect Dis 183: 1554–1564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson H, Franco E, Pintos J, Bergeron J, Arella M, Tellier P (2000) Determinants of low-risk and high-risk cervical human papillomavirus infections in Montreal University students. Sex Transm Dis 27: 79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau MC, Franco EL, Villa LL, Sobrinho JP, Termini L, Prado JM, Rohan TE (2000) A cumulative case–control study of risk factor profiles for oncogenic and nononcogenic cervical human papillomavirus infections. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 9: 469–476 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellors JW, Mahony JB, Kaczorowski J, Lytwyn A, Bangura H, Chong S, Lorincz A, Dalby DM, Janjusevic V, Keller JL (2000) Prevalence and predictors of human papillomavirus infection in women in Ontario, Canada. Survey of HPV in Ontario Women (SHOW) Group. Can Med Assoc J 163: 503–508 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin H-R, Lee D-H, Herrero R, Smith JS, Vaccarella S, Hong S-H, Jung K-Y, Kim H-H, Park U-D, Cha H-S, Park S, Touze A, Munoz N, Snijders P, Meijer C, Coursaget P, Franceschi S (2003) Prevalence of human papillomavirus infection in women in Busan, South Korea. Int J Cancer 103: 413–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JS, Green J, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Appleby P, Peto J, Plummer M, Franceschi S, Beral V (2003) Cervical cancer and use of hormonal contraceptives: a systematic review. Lancet 361: 1159–1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli A, Talamanca IF, Lauria L (2000) Patterns of contraceptive use in 5 European countries. European Study Group on Infertility and Subfecundity. Am J Public Health 90: 1403–1408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svare EI, Kjaer SK, Poll P, Bock JE (1997) Determinants for contraceptive use in young, single, Danish women from the general population. Contraception 55: 287–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan SH, Brown WL (1981) Oral contraceptive use, sexual activity, and cervical carcinoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol 139: 52–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos M, Bosch F, Kummer A, Shah K, Snijders PJ, Peto J, Meijer CJ, Munoz N (1999) Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol 189: 12–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ylitalo N, Sorensen P, Josefsson AM, Magnusson PK, Andersen PK, Ponten J, Adami HO, Gyllensten UB, Melbye M (2000) Consistent high viral load of human papillomavirus 16 and risk of cervical carcinoma in situ: a nested case–control study. Lancet 355: 2194–2198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]