Abstract

Objectives. We sought to examine sexual violence victimization in childhood and sexual risk indicators in young adulthood in a primarily Latina and Black cohort of “mostly heterosexual” and heterosexual women in the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN).

Methods. In 2000, a comprehensive survey that assessed sexual orientation, sexual risk indicators, and sexual abuse victimization was completed by 391 young women (aged 18 to 24 years) who had participated in PHDCN. We used multivariable regression methods to examine sexual orientation group differences in sexual risk indicators and to assess whether childhood sexual abuse may mediate relationships.

Results. Compared with self-reported heterosexual women, self-reported “mostly heterosexual” women were more likely to report having been the victim of childhood sexual abuse, to have had a sexually transmitted infection, to report an earlier age of first sexual intercourse, and to have had more sexual partners. Childhood sexual abuse did not mediate relationships between sexual orientation and sexual risk indicators.

Conclusions. Our findings add to the evidence that “mostly heterosexual” women experience greater health risk than do heterosexual women. In addition, “mostly heterosexual” women are at high risk for having experienced childhood sexual abuse.

Adolescent girls and young women who report having attractions to both genders but who may not describe themselves as bisexual make up an estimated 6% to 10% of female youth.1,2 This group may be several times larger than the proportion of adolescent girls and young women who describe themselves as lesbian or bisexual, which is estimated to be approximately 1% to 2% of girls and young women.1,3,4 Recent research has documented that this newly identified subgroup of adolescent girls who describe themselves as “mostly heterosexual” are at higher risk for tobacco use, binge drinking, eating disorder symptoms, and sexual risk behaviors compared with those who describe themselves as heterosexual.1,5–7

Little is known about factors that may contribute to elevated rates of high-risk behaviors in this group. Based on research findings about the effects of sexual violence victimization on subsequent risk behaviors in multiple health domains,8–12 it is possible that violent victimization in childhood may be a contributor to elevated health risks experienced by “mostly heterosexual” girls and women. History of childhood sexual abuse, defined as sexual abuse victimization occurring before the age of 18 years,13 is associated with greater likelihood to engage in sexual risk behaviors in adolescence and adulthood, which increases risk for unwanted pregnancy, and HIV infection and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).8–12 A meta-analysis of published studies of the effects of childhood sexual abuse found that across 37 studies (N = 25 367), there was a minimum 14% increase in the risk of engaging in early sexual behavior for those sexually abused as children.8 Another meta-analysis of the relationship between childhood sexual abuse and HIV risk behavior among women found that across 46 studies, there was an increased risk of unprotected sexual activity; having multiple partners; engaging in sexual intercourse in exchange for money, drugs, or shelter; and sexual revictimization in adulthood.9

It has been proposed that youths whose same-gender attractions or same-gender sexual involvement is known to others may be singled out for maltreatment and abuse by parents, other adults, or other youths because of antigay bias.14,15 This pattern of maltreatment may be relevant not only for lesbian, gay, and bisexual but also for “mostly heterosexual” youth. Saewyc et al. found in a school-based sample of girls in grades 7 to 12 in British Columbia that an estimated 23% to 27% of “mostly heterosexual” girls compared with 15% to 21% of heterosexual girls reported having experienced sexual abuse in their lifetimes.16 It is plausible that elevated risk behaviors experienced by “mostly heterosexual” girls and young women are in part sequelae of violence victimization that occurred earlier in childhood. Violence victimization, then, may be a mediator of the relationship between “mostly heterosexual” orientation and risk indicators.

The 2 aims of our study were (1) to compare patterns of sexual risk indicators between “mostly heterosexual” and heterosexual young women in a representative, multi-ethnic sample and (2) to examine childhood sexual abuse that occurs temporally prior to onset of sexual risk indicators as a possible mediator of a relationship between “mostly heterosexual” orientation and sexual risk indicators.

METHODS

Study Sample

We collected data as part of the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN), a multilevel, prospective cohort study of 6226 children and adolescents, their caregivers, and their neighborhoods. Sampling was done in stages. First, a stratified, representative sample of 80 neighborhood clusters was selected from the overall 343 neighborhood clusters in the city of Chicago, Ill. Neighborhood clusters diverse in socioeconomic status and racial/ethnic composition were purposefully selected. Then, sampling for the cohort study was carried out among residents of the 80 selected neighborhood clusters, after screening approximately 35000 randomly sampled households for children of 7 eligible age groups (in utero, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18 years). For the current study, we used data collected from 1328 young people aged within 6 months of 15 or 18 years at baseline in 1994. In this baseline sample, 671 participants were girls. Participants were primarily Latina or Black, of diverse socioeconomic position, and represented families with children of the eligible ages living in Chicago. Overall, 1871 eligible adolescents had been invited to join the original cohort in these 2 age groups, with an enrollment rate of 71% at baseline. A full description of the PHDCN study has been presented elsewhere.17

Measures

In 2000, a comprehensive in-person interview and self-report questionnaire that assessed sexual orientation, sexual risk indicators, and sexual abuse victimization was administered to PHDCN participants who were aged 18 to 24 years at that time. The item on sexual orientation was adapted from one used on the Growing Up Today Study and the Minnesota Adolescent Health Survey.1,18 The item assessed feelings of attraction with 6 response options: “Which of the following best describes your feelings? 100% heterosexual (only attracted to persons of the opposite sex); mostly heterosexual (attracted to both, but mostly persons of the opposite sex); bisexual (pretty much equally attracted to both men and women); mostly homosexual (attracted to both, but mostly persons of the same sex); 100% homosexual (gay/lesbian; only attracted to persons of the same sex); not sure.”

The survey assessed a range of sexual risk indicators, including age at first sexual intercourse, age at first pregnancy, lifetime number of sexual partners, and ever having had an STI. In addition, the survey assessed sexual abuse experiences, including molestation (unwanted sexual touching) and rape (having been forced to have oral, anal, or vaginal intercourse against one’s will). Sexual abuse questions were adapted from a previously validated survey by Leserman et al.19 Respondents who reported having experienced sexual abuse were subsequently asked at what age they first experienced the form of abuse that they reported farthest down the list of abusive acts. The list was purposely ordered from least to most severe. For instance, if a participant reported having experienced both unwanted sexual touching and forced vaginal intercourse, then age at first occurrence of forced vaginal intercourse was recorded. Participants were coded as having experienced childhood sexual abuse if they reported sexual victimization that occurred before the age of 18 years.

Statistical Analyses

Among those who participated at baseline, 70% of participants completed their second follow-up interview in 2000–2001. After dropping 9% of participants because of missing data, our analytic sample consisted of a total of 410 young women who responded to the questions that addressed sexual abuse victimization on the 2000 PHDCN survey. Of those, 391 completed the item on sexual orientation: 337 (86%) described themselves as “100% heterosexual,” 33 (8%) as “mostly heterosexual,” 5 (1%) as “bisexual,” 7 (2%) as “mostly homosexual” or “100% homosexual,” and 9 (2%) as “not sure.” Because of the very small sample sizes in the latter 3 groups, analyses were restricted to the 370 participants who described themselves as “mostly heterosexual” and “100% heterosexual.”

In the analytic sample, 47% of participants were Latina, 37% were Black, 15% were White, and 1% was of other races or ethnicities. The mean age for both “mostly heterosexual” and heterosexual participants was 21 years. Compared with those who responded to the sexual orientation item on the survey in 2000, those who did not were more likely to be Black and less likely to be Latina; there were no differences between responders and nonresponders in parent or caregiver education or neighborhood concentrated poverty.

Basic descriptive analyses were carried out to examine patterns of sexual risk indicators in adolescence and young adulthood among “mostly heterosexual” and heterosexual young women. Outcome variables included age at first sexual intercourse, age at first pregnancy, and lifetime number of sexual partners. Descriptive analyses were also carried out to examine sexual orientation group patterns in basic demographics, socioeconomic position, and report of ever having been diagnosed with an STI, and to compare orientation group disparities in childhood sexual abuse victimization, which was hypothesized to mediate relationships between orientation and sexual risk indicators. In addition, we created Kaplan–Meier survival curves and tested multivariable Cox proportional hazards models to estimate sexual orientation group differences in time to childhood sexual abuse onset. These models generated hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

To further examine sexual orientation group disparities in sexual risk indicators, we tested 3 sets of multivariable regression models, with 1 set for each outcome variable. In all models, heterosexuals served as the reference group and age, race/ethnicity, parents’ education, and neighborhood concentrated poverty based on US Census 2000 data for census tracts20 were included as covariates.11

For 2 outcome variables—age at first sexual intercourse and age at first pregnancy—we tested multivariable Cox proportional hazards models to estimate orientation group differences in time to outcome event. For the outcome variable lifetime number of sexual partners, we used multivariable linear regression models to test orientation group differences in mean number of partners. The lifetime number of sexual partners ranged from 0 to 99 among the “mostly heterosexual” women, and from 0 to 38 among heterosexual women, with 95% of all respondents reporting between 0 and 10. Because lifetime number of sexual partners was skewed toward the higher values, the variable was coded from 0 to 11 to minimize effects of outliers. For the recoded variable, a value from 0 to 10 represented actual number of partners reported, and a value of 11 represented 11 or more lifetime sexual partners; 5% of the cohort’s values were recoded to 11.

Finally, to test whether childhood sexual abuse may mediate a relationship between sexual orientation and sexual risk indicators, a term representing childhood sexual abuse was added to the multivariable model for each outcome, and effect estimates for models with and without the sexual abuse term were compared for evidence of mediation.21 Childhood sexual abuse terms were defined to be temporally appropriate for each outcome: for age at first sexual intercourse and lifetime number of sexual partners, childhood sexual abuse was restricted to report of first occurrence before first sexual intercourse. For age of first pregnancy, childhood sexual abuse was restricted to report of first occurrence before first pregnancy. Although STI history is also an important sexual risk indicator, we did not include this factor as an additional outcome variable in mediation analyses because age at first diagnosis with an STI was not available; therefore, temporal ordering relative to childhood sexual abuse could not be established. All analyses accounted for correlated data that resulted from the PHDCN sampling design and were carried out with SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) with α set at .05.

RESULTS

In the full sample, “mostly heterosexuals” made up 42% of young women who reported having partners of both genders; the remainder of young women with both-gender partners was made up of those who described themselves as “100% heterosexual” (30%); “bisexual” (15%); “mostly homosexual” (9%); and “100% homosexual” (3%). Comparing the subset of participants who described themselves as “100% heterosexual” to those who described themselves as “mostly heterosexual,” 86% versus 52% had sexual experience with male partners only, 3% versus 42% had sexual experience with both male and female partners, 0.6% versus 3% had experience with female partners only, and 10% versus 3% had no sexual experience.

“Mostly heterosexual” and heterosexual participants were similar in age at the time of the interview (P=.84), race/ethnicity (P=.36), and proportion living in neighborhoods characterized by concentrated poverty (P=.65); however, “mostly heterosexual” women reported higher parent or caregiver education than did heterosexuals (P=.03). For instance, 28% of “mostly heterosexual” compared with 10% of heterosexual women reported that 1 or more of their parents or caregivers had earned at least an undergraduate degree.

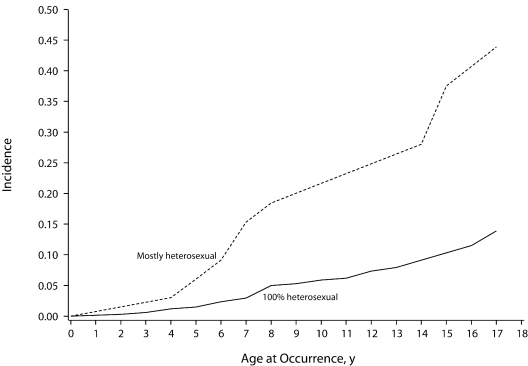

“Mostly heterosexual” women were more likely than were heterosexual women to report having been the victim of childhood sexual abuse (45% vs 15%; P < .001). Among those who reported unwanted sexual touching or rape before they were aged 18 years, the mean age of first occurrence was 11 years for both groups. Figure 1 ▶ presents Kaplan–Meier survival curves that represent the cumulative proportion in each sexual orientation group who reported onset of sexual abuse each year through childhood and adolescence. Results of multivariable Cox proportional hazards models estimate that “mostly heterosexual” young women had an almost 4 times greater hazard of experiencing childhood sexual abuse than did heterosexual young women (HR = 3.9; 95% CI = 2.1, 7.1).

FIGURE 1—

Kaplan–Meier survival curves of age at childhood sexual abuse occurrence in “mostly heterosexual” and heterosexual young adult women (aged 18–24 years): Chicago, Ill, 2000–2001.

Note. Hazard ratio = 3.9 (95% confidence interval = 2.1, 7.1).

The large majority of both “mostly heterosexual” and heterosexual participants reported ever having had sexual intercourse (91% vs 88%; P = .53); however, among the subset of participants who had ever had sexual intercourse (n = 324), “mostly heterosexual” women reported an earlier mean age of first sexual intercourse than did heterosexual women (age 15.2 vs 16.3 years; P < .01) and a greater mean number of sexual partners in their lifetimes (5.9 vs 2.6; P < .001), with the recoded values for number of sexual partners as described earlier.

In the analytic sample as a whole, the “mostly heterosexual” group was marginally more likely to report pregnancy before age 18 years than was the heterosexual group (47% vs 29%, respectively; P = .05); however, in the subset who reported ever having had sexual intercourse, there was no group difference in age at first pregnancy (P = .55). “Mostly heterosexual” were more likely than heterosexual participants to report having ever been diagnosed with an STI (43% vs 15%; P < .001).

Statistically significant sexual orientation –group differences for some outcomes persisted in multivariable models. Results of multivariable Cox proportional hazards models, after we controlled for age, race/ethnicity, parent or care-giver education, and neighborhood concentrated poverty, indicated that “mostly heterosexual” women experienced first sexual intercourse at younger ages than did heterosexual women (HR = 1.5; 95% CI = 1.0, 2.4), but differences were not observed in age at first pregnancy (HR = 1.1; 95% CI = 0.6, 1.8). Results of multivariable linear regression models, after we controlled for the same covariates, indicated that “mostly heterosexual” women reported a greater number of sexual partners in their lifetimes compared with heterosexual women (b=3.1; SE=0.6; Table 1 ▶, base models).

TABLE 1—

Results of Multivariable Regression Models Testing Childhood Sexual Abuse as a Mediator of Associations Between Sexual Orientation and Sexual Risk Indicators in Multiethnic “Mostly Heterosexual” and Heterosexual Young Women Aged 18–24 Years: Chicago, Ill, 2000–2001

| Model 1: Age at First Intercoursea HR (95% CI) | Model 2: Age at First Pregnancyb HR (95% CI) | Model 3: Lifetime No. of Sexual Partners,c b (SE) | |

| Total sample, no. | 343 | 307 | 344 |

| Base model | |||

| Heterosexual (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| “Mostly heterosexual” | 1.5* (1.0, 2.4) | 1.1 (0.6, 1.8) | 3.1** (0.6) |

| Mediation model | |||

| Heterosexual (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| “Mostly heterosexual” | 1.5 (1.0, 2.3) | 1.0 (0.6, 1.7) | 3.1** (0.6) |

| Childhood sexual abuse | 1.4* (1.1, 1.9) | 1.5 (1.0, 2.1)* | –0.1 (0.5) |

Note. HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval. In all base models we controlled for age, race/ethnicity, parent or caregiver education, and neighborhood concentrated poverty. In all mediation models we controlled for childhood sexual abuse experienced prior to outcome in addition to age, race/ethnicity, parent or caregiver education, and neighborhood concentrated poverty.

aMultivariable HR and 95% CI for HR from Cox proportional hazards model; in mediation model, age of childhood sexual abuse first occurrence younger than age at first sexual intercourse.

bMultivariable HR and 95% CI for HR from Cox proportional hazards model; in mediation model, age of childhood sexual abuse first occurrence younger than age at first pregnancy.

cMultivariable b coefficient and SE for b from linear regression model; in mediation model, age of childhood sexual abuse first occurrence younger than age at first sexual intercourse.

* P < .05; **P < .001.

In analyses to test childhood sexual abuse as a mediator of relationships between sexual orientation and sexual risk indicators, introduction of the abuse term to the multivariable base models did not attenuate effect estimates for the “mostly heterosexual” group (Table 1 ▶, mediation models).

DISCUSSION

We examined patterns in sexual risk and victimization in heterosexual and “mostly heterosexual” young women and the possible contribution of childhood sexual abuse history to orientation group disparities in sexual risk. Among young women participating in the PHDCN, those describing themselves as “mostly heterosexual” reported higher rates of childhood sexual abuse than did those describing themselves as a heterosexual; nearly half of “mostly heterosexual” women reported having experienced sexual violence victimization before the age of 18. In addition, “mostly heterosexual” women were more likely to have ever been diagnosed with an STI and reported an earlier age of first intercourse and greater number of sexual partners in their lifetimes compared with heterosexual women.

Our findings are consistent with recent work by Saewyc et al., who found “mostly heterosexual” adolescent girls, compared with heterosexual girls, reported higher rates of HIV risk indicators, such as early age of first sexual intercourse, higher number of lifetime sexual partners, and history of a diagnosis with an STI,6 and reported higher lifetime rates of sexual abuse.16

Prior studies have examined health risks for adolescents with sexual partners of both genders. In the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, adolescent girls with both male and female sexual partners, compared with girls with male sexual partners only, were more likely to have performed sexual acts in exchange for drugs or money, a behavior likely to put them at high risk for HIV infection.22 A study based on representative samples of Massachusetts and Vermont high school students found that adolescents with sexual partners of both genders were more likely to have been forced to have sexual intercourse against their will, compared with adolescents with other-gender partners only.23 Although these prior studies do not report how many of these youth would describe themselves as “mostly heterosexual,” we found that in our study, which is based on a cohort primarily made up of Latina and Black women, that among women with partners of both genders, more than 40% indicated they were “mostly heterosexual,” whereas nearly one third described themselves as “100% heterosexual” and one quarter as “bisexual” or “mostly homosexual,” with just 3% as “100% homosexual.”

Very little is known about factors that may explain why “mostly heterosexual” women have higher health risks compared with heterosexual women. A large cohort study of youths found “mostly heterosexual” adolescent girls reported greater depressive symptoms, lower self-esteem, and more alcohol use among family members compared with heterosexual girls.7 A qualitative study designed in part to explore how youths interpret the term mostly heterosexual found that adolescents and young adults who described themselves as “mostly heterosexual” felt the term reflected the relative balance of the strength or frequency of their attractions to the same versus the opposite gender.24

We hypothesized that sexual abuse occurring prior to onset of sexual risk indicators would mediate the relationship between sexual orientation and sexual risk indicators; however, results of mediation analyses did not support this hypothesis. Introduction of the childhood sexual abuse term to the multivariable base models did not attenuate effect estimates for the “mostly heterosexual” group relative to heterosexuals. There may be a number of explanations for these findings. First, there may be misclassification of both exposure and outcome as a result of retrospective reporting or discomfort about revealing an abuse history or sexual risk behaviors. Second, the estimated magnitude of sexual orientation–group differences in abuse history may be inflated as a result of response bias if sexual-minority women are more willing than are heterosexual women to report having experienced sexual victimization or if victims of childhood sexual abuse are more willing than are other women to report having a minority sexual orientation.16,25,26

Third, it is plausible that sexual orientation–group disparities in sexual risk indicators are driven more by childhood sexual abuse that occurs after adolescents and young women have become sexually active, rather than before. In our analyses, classification of childhood sexual abuse was restricted to sexual abuse that occurred before the onset of the sexual risk indicator outcome. This restriction was appropriate for our hypothesized temporal ordering, specifically that childhood sexual abuse may mediate relationships between sexual orientation and sexual risk indicator outcomes. Sexual abuse can occur after an adolescent has become sexually active, however, and it is plausible that abuse at this point may lead an adolescent girl to alter her sexual behavior, either heightening or reducing involvement in sexual risk behaviors.

Fourth, it is possible that factors other than childhood sexual abuse may contribute to higher rates of sexual risk indicators among “mostly heterosexual” girls and women. For example, it has been proposed that youths who experience psychological distress that results from conflict or social isolation related to their same-gender attractions or same-gender sexual involvement may initiate alcohol and other drug use or other risk behaviors in an effort to cope, but these unhealthful coping strategies may then make them vulnerable to abuse by parents, other adults, or other youth.4,27 Sexual orientation–group disparities in violence victimization then may be a sequela of group differences in risk behaviors, rather than the reverse. Future research will need to explore the contribution of these alternate hypothesized mechanisms to sexual orientation–group patterns in risk indicators.

Limitations of our study include the relatively small sample size of “mostly heterosexual” participants and analyses based on data collected at a single time point, when respondents were asked to recall their ages at sexual victimization and at onset of sexual risk indicators. In addition, age of sexual violence victimization used in analyses was defined as age at which the most severe type of childhood sexual abuse reported had first occurred; therefore, we were not able to account for less-severe abuse that may have begun before the more severe forms, nor were we able to account for duration or frequency of sexual abuse occurrence.

Our findings add to the evidence that the health experience of “mostly heterosexual” girls and women is distinct from that of heterosexual peers in a range of health domains. Given the patterns in sexual risk indicators observed in our study, “mostly heterosexual” young women may be especially vulnerable to illnesses associated with high-risk sexual behavior, such as pelvic inflammatory disease, HIV, human papillomavirus, and cervical cancer. In addition, this subpopulation of young women may need support from community agencies and service providers to cope with past experiences of victimization. Because these women do not identify as bisexual or lesbian, they may not seek out victim support services within bisexual or lesbian communities, which adds urgency to the need for agencies that serve the general population to ensure that sensitive and appropriate care is provided for all sexual-minority women, including those who are “mostly heterosexual.” Public health professionals and health care providers need to be aware that “mostly heterosexuals” represent an underrecognized population not identified by standard sexual orientation identity questions that include only the options heterosexual, bisexual, and lesbian/gay. Further investigation into the reasons underlying the high rates of violence victimization in this subgroup of young women is of paramount importance.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Leadership Education in Adolescent Health Project, Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration (grant T71-MC00009-16), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (grant R49/ CCR118602), and the Aerosmith Fund. The Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN) was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute of Justice, and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

The authors would like to thank Kathy McGaffigan and Lisa Prokop for their contributions to this article and the young people and family members who participated in the PHDCN. The authors also acknowledge the contributions of the scientific directors of the PHDCN: Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, Felton Earls, Stephen Raudenbush, and Robert Sampson.

Note. This work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Human Participant Protection This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Harvard School of Public Health.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors S. B. Austin was responsible for study conceptualization, data analysis and interpretation, and article preparation. A. L. Roberts was responsible for data analysis and interpretation and article preparation. H. L. Corliss was responsible for data interpretation and article preparation. B. E. Molnar was responsible for study conceptualization, data interpretation, and article preparation.

References

- 1.Austin SB, Ziyadeh N, Fisher LB, Kahn JA, Colditz GA, Frazier AL. Sexual orientation and tobacco use in a cohort study of US adolescent girls and boys. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:317–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services. National Survey of Family Growth. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/nsfg/nsfgback.htm. Accessed August 24, 2007.

- 3.Bontempo DE, D’Augelli AR. Effects of at-school victimization and sexual orientation on lesbian, gay, or bisexual youths’ health risk behavior. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30:364–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garofalo R, Wolf RC, Kessel S, Palfrey SJ, DuRant RH. The association between health risk behaviors and sexual orientation among a school-based sample of adolescents. Pediatrics. 1998;101:895–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Austin SB, Ziyadeh N, Kahn JA, Camargo CA Jr, Colditz GA, Field AE. Sexual orientation, weight concerns, and eating-disordered behaviors in adolescent girls and boys. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:1115–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saewyc E, Skay C, Richens K, Reis E, Poon C, Murphy A. Sexual orientation, sexual abuse, and HIV-risk behaviors among adolescents in the Pacific Northwest. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1104–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ziyadeh N, Prokop LA, Fisher LB, et al. Sexual orientation, gender, and alcohol use in a cohort study of US adolescent girls and boys. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87:119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paolucci EO, Genuis ML, Violato C. A meta-analysis of the published research on the effects of child sexual abuse. J Psychol. 2001;135:17–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arriola KR, Louden T, Doldren MA, Fortenberry RM. A meta-analysis of the relationship of child sexual abuse to HIV risk behavior among women. Child Abuse Negl. 2005;29:725–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Molnar BE, Shade SB, Kral AH, Booth RE, Watters JK. Suicidal behavior and sexual/physical abuse among street youth. Child Abuse Negl. 1998;22:213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molnar BE, Browne A, Cerda M, Buka SL. Violent behavior by girls reporting violent victimization: a prospective study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:731–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molnar BE, Berkman LF, Buka SL. Psychopathology, childhood sexual abuse and other childhood adversities: relative links to subsequent suicidal behaviour in the US. Psychol Med. 2001;31:965–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.US Department of Health and Human Services. Child Maltreatment 2004. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2006.

- 14.D’Augelli AR, Hershberger SL, Pilkington NW. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth and their families: disclosure of sexual orientation and its consequences. Am J Orthopsych. 1998;68:361–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pilkington NW, D’Augelli AR. Victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth in community settings. J Community Psychol. 1995;23:34–56. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saewyc EM, Skay CL, Pettingell SL, et al. Hazards of stigma: the sexual and physical abuse of gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents in the United States and Canada. Child Welfare. 2006;85:195–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Earls F, Buka SL. Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods: Technical Report. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Justice; 1997.

- 18.Remafedi G, Resnick M, Blum R, Harris L. Demography of sexual orientation in adolescents. Pediatrics. 1992;89(4 pt 2):714–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leserman J, Drossman DA, Li Z. The reliability and validity of a sexual and physical abuse history questionnaire in female patients with gastrointestinal disorders. Behav Med. 1995;21:141–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.US Census 2000. American FactFinder. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2003. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov/home/saff/main.html. Accessed July 24, 2007.

- 21.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Udry JR, Chantala K. Risk assessment of adolescents with same-sex relationships. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31:84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robin L, Brener ND, Donahue SF, Hack T, Hale K, Goodenow C. Associations between health risk behaviors and opposite-, same-, and both-sex sexual partners in representative samples of Vermont and Massachusetts high school students. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002; 156:349–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Austin SB, Conron KJ, Patel A, Freedner N. Making sense of sexual orientation measures: findings from a cognitive processing study with adolescents on health surveys. J LGBT Health Res. 2006;3:55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Austin SB, Jun H-J, Jackson B, et al. Abuse history in childhood and adolescence among lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual women in the Nurses’ Health Study II. Under review.

- 26.Corliss HL, Cochran SD, Mays VM. Reports of parental maltreatment during childhood in a United States population-based survey of homosexual, bisexual, and heterosexual adults. Child Abuse Negl. 2002; 26:1165–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Russell ST, Driscoll AK, Truong N. Adolescent same-sex romantic attractions and relationships: implications for substance use and abuse. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:198–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]