Abstract

Objectives. We sought to document the frequency, circumstances, and consequences of prescription medication–sharing behaviors and to use a medication-sharing impact framework to organize the resulting data regarding medication-loaning and -borrowing practices.

Methods. One-on-one interviews were conducted in 2006, and participants indicated (1) prescription medicine taken in the past year, (2) whether they had previously loaned or borrowed prescription medicine, (3) scenarios in which they would consider loaning or borrowing prescription medicine, and (4) the types of prescription medicines they had loaned or borrowed.

Results. Of the 700 participants, 22.9% reported having loaned their medications to someone else and 26.9% reported having borrowed someone else’s prescription. An even greater proportion of participants reported situations in which medication sharing was acceptable to them.

Conclusions. Sharing prescription medication places individuals at risk for diverse consequences, and further research regarding medication loaning and borrowing behaviors and their associated consequences is merited.

The health care industry has witnessed a gradual transition from a provider-centered model in which patients are relatively passive recipients of care to a more patient-centered model that empowers patients as consumers of health services.1 As a result of this shift, the role of the patient in medical errors has received increased scrutiny. One such source of error or unsafe practice is medication sharing, defined as giving medications to someone else (“loaning”) or taking someone else’s medication (“borrowing”).2

Previous research on medication sharing has focused on illicit use3–7 or accidental exposure to pharmaceuticals harmful to pregnancy.2 Simoni-Wastila et al., for example, identified and estimated the prevalence of risk and protective factors for the illicit (“problem”) use of prescription drugs.8 McCabe et al. similarly examined the prevalence of illicit (“non-medical”) use of prescription drugs, particularly among secondary school students.9 Both studies, and others that similarly investigate illicit use, adopt a framework that focuses on 4 categories of abusable prescription medication: narcotics, stimulants, minor tranquilizers, and sedatives and hypnotics.

Daniel et al.2 examined prescription medication sharing more broadly (i.e., not limited to illicit use of abusable drugs); however, they focused primarily on one particular outcome: the potential for exposure by women who are or may become pregnant to pharmaceuticals with teratogenic properties. They surveyed 1568 individuals aged 9 to 18 years about their medication sharing behaviors. A sizable percentage of girls and boys (20.1% and 13.4%, respectively) reported sharing medications. Moreover, this behavior was reported to occur frequently (i.e., more than “1 time only” for emergency use), and the rates of sharing increased with age. The study confirmed that accidental exposure to pharmaceuticals with teratogenic properties was an actual risk: approximately 10% of the females in the sample indicated they would borrow medication if they “wanted something strong for pimples or oily skin.”

Although illicit use of prescription medications and accidental exposure to teratogenic pharmaceuticals are significant public health concerns, the implications and consequences of medication sharing extend well beyond these concerns. No research to date, however, has holistically considered the broader societal and personal issues that arise from prescription medication sharing.

A FRAMEWORK FOR CONSIDERING MEDICATION SHARING

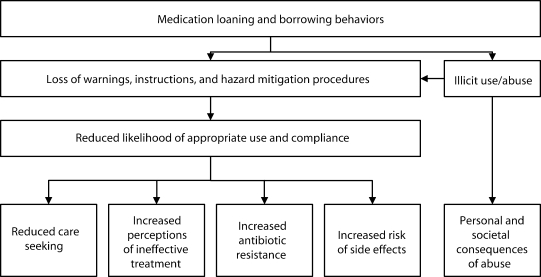

We propose a framework for considering the potential consequences of prescription medication sharing and present data regarding prescription loaning and borrowing behaviors among a diverse population. As illustrated in Figure 1 ▶, the medication sharing impact framework captures many of the varied implications of medication sharing, several of which have received little or no attention to date despite their potential for considerable negative public and personal health consequences.

FIGURE 1—

The medication sharing impact framework.

As a broad class of behavior, medication sharing appears to be associated with 2 distinct and not mutually exclusive classes of consequences: those that arise from abuse and illegal use and those that arise from loss of warnings and instructions. As previously noted, a number of researchers have spent considerable effort investigating the first class of consequences.3,6,7,9–12 In addition to being a public health concern in its own right, such illicit use, through sharing, may lead directly to the second class of consequences: loss of warnings, instructions, and other hazard mitigation procedures. This second class of consequences, which has received less research attention, can also arise outside of the realm of illicit use and abuse.

Prescription medication borrowers receive no counseling from prescribing and dispensing providers, thus bypassing established gatekeeping mechanisms, such as those enacted to avoid dispensation of isotretinoin to those who are or may become pregnant.13,14 It seems unlikely that individuals loaning medication will verbally convey the associated instructions and warnings or pass along the medication packaging and materials. This loss of instructions and of hazard mitigation procedures can lead to inappropriate use of prescription medications and noncompliance with medication instructions. There are at least 4 potentially significant interrelated consequences of inappropriate use and noncompliance.

First, bypassing traditional channels may lead to reduced or delayed care seeking. Individuals who borrow a medication to treat particular symptoms will not undergo diagnosis or receive follow-up care from a provider. This can delay appropriate treatment of the underlying condition. Two examples serve to illustrate the issue. An individual has a painful sensation in his penis. The individual knows someone who had a similar condition and borrows some antibiotics to treat “the drip” he has self-diagnosed. The condition clears in about a week, only to return a year later. This time the individual visits a clinic and is correctly diagnosed with herpes simplex. However, in the intervening year, he has had sexual intercourse with 6 individuals, 3 of them anonymously. In a second example, an individual experiences “heartburn” for a period of time. She borrows a common prescription medication from a friend with a similar problem. The problem clears with use of the medication. Six months later, the problem recurs and the individual is diagnosed with end-stage esophageal cancer. In both cases, the public and personal consequences of sharing are considerable. Even when the consequences are not as significant, such self-treatment will not be documented in the person’s medical record and could therefore lead to miscommunication and inappropriate follow-up.

A second possible consequence of reduced appropriate use and compliance is increased perceptions of ineffective treatment. Individuals may correctly diagnose themselves on the basis of the similarity of their own symptoms to those of others, and they may also borrow an appropriate medication for their diagnosis. However, if the dosage or course of treatment is not correct for the individual, the medication may be ineffective. This can lead to the perception that a particular treatment is ineffective when in fact the issue is one of compliance with the medication regimen as opposed to the appropriateness of the medication itself.

Consider the case of a mother whose young daughter has a very painful recurrent sore throat. After several weeks of trying various antibiotics that she has borrowed from her friends who “had them left over,” the mother finally takes her daughter to a health care provider (note, again, the delay caused by borrowing medications). The conversation between the mother and provider is not as clear as it could be because she now “knows” that her daughter’s illness is not something that requires “just” an antibiotic because she has tried several of those. Because of these previous less-than-full regimens of other antibiotics, the provider may prescribe a broader-spectrum antibiotic than is necessary. Of course, beyond confusion and delay, the perception of medication ineffectiveness that may result from borrowing prescriptions could lead to the decision that the medication does not work for the individual and that he or she simply needs to “live with” the condition. In either case, suboptimal care is the result.

The issue of antibiotics is directly related to the third potential consequence: increased antibiotic resistance. Both the borrowing and loaning of antibiotic medications is an indication that less than a full course of medicine is being followed. As a result, widespread sharing of antibiotics is likely to promote the development of resistant bacterial strains.

Finally, prescription medication sharing may lead to an increased risk of side effects. Warnings and gatekeeping procedures are bypassed by medication sharing, and the risk of incorrect use probably increases as a result of such omission. Medication allergies, medication interactions, and other medication side effects may all be affected. The work by Daniel et al.2 on the potential for exposure to pharmaceuticals with teratogenic properties represents one important effort to understand this type of consequence of medication sharing. What would happen if a young woman asked a friend of hers what he had done to clear up his really bad case of acne and that friend provided her with a week’s worth of isotretinoin? Would he be likely to pass along the pregnancy warnings? What if she became pregnant 3 weeks later?

Different classes of prescription medication entail varying types and levels of risk within the medication sharing impact framework. Additionally, the likelihood of engaging in loaning and borrowing and the concomitant risk of experiencing consequences may vary by patient characteristics. Adolescents, for example, comprise a segment of the population potentially at greater risk because they often lack an accurate understanding of critical drug-related information.15 Moreover, there is some evidence that adolescent girls may be more likely than adolescent boys or individuals in other age groups to engage in potentially risky prescription medication sharing behaviors.2

Another at-risk segment of the population comprises those who speak English as a second language. Hispanics constitute the largest ethnic minority group (15%) in the United States,16 and many of them speak English as a second language. These individuals may be at increased risk for committing medication errors when pharmaceutical advertisements, instructions, and warnings, printed in English, are misinterpreted. Also at potentially heightened risk are individuals classified as having low health literacy, which is commonly defined as having difficulty reading, understanding, and using health-related information. One study estimated that almost half (48%) of adults in the United States have difficulty understanding medication labels.17 Nabors et al. suggest that low health literacy within the adolescent population is also quite high.18 In a recent study, those with low health literacy, as indicated on the brief survey Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM),19,20 were approximately 30% as likely as those with high health literacy to correctly comprehend pharmaceutical warning labels.21 These findings suggest the importance of including participant characteristics in investigations of medication sharing.

In addition to highlighting the need for a broader perspective and increased attention toward medication sharing, and suggesting a framework for organizing such efforts, we conducted an exploratory study to survey overall prevalence of sharing, the types of medications shared, the situations in which sharing occurs, and the demographic characteristics that may influence sharing. The resulting data add to our understanding of medication sharing behaviors and describe the potential for various adverse consequences.

METHODS

Participants

We assessed the medication sharing behaviors of 700 individuals through nationally distributed one-on-one interviews conducted in 2006 in public spaces in the following cities: Atlanta, Georgia; Cleveland, Ohio; Dallas, Texas; Greenville, South Carolina; Miami, Florida; Los Angeles, California; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Phoenix, Arizona; South Bend, Indiana; and Tacoma, Washington (70 participants per area). Participants ranged in age from 12 to 44 years; adolescents aged 12 to 17 composed 19.7% of the sample, with the remainder evenly distributed across the remaining age range. In terms of gender, 73% of the sample were female and 27% were male. The sample was ethnically diverse: 48.3% White, 24.3% African American, 24.1% Hispanic, and 1% Asian. Thirty-nine percent of the respondents reported Spanish as their primary language; these individuals were interviewed in their preferred language. The brief version of the REALM, called the REALM-R, was administered to assess health literacy. The REALM has been shown to have adequate construct, concurrent, and test–retest validity.19,20 A total of 42.9% of the sample were determined to have low health literacy; this figure coincides with recent national estimates.17

Procedure

Participants completed the REALM-R and were then read an orientation paragraph:

A prescription means the doctor has signed a paper so that you can get a medicine. It usually has your name on it. It does not mean medicines like Tylenol or aspirin that you can buy at any grocery or drug store. Medication sharing means that you give your prescription medication to someone else or you take their medicine.

Participants were then asked, (1) “How many different prescription medications of your own have you taken in the past year?”; (2) “Have you ever shared your prescription medicine with someone else?” (loaning); (3) “Has anyone ever shared their prescription medicine with you?” (borrowing); and (4) to answer yes or no to each of 13 medication-sharing scenarios. In addition, they responded to an open-ended question that inquired about “other situations in which you might share prescription medicine.”

Participants who indicated loaning or borrowing were asked to indicate whether they had loaned or borrowed the following: allergy medications, pain medications, mood medications, antibiotics, acne medication, birth control pills, or other medications. Several common examples were provided. Participants provided demographic information and were presented $20 gift certificates as compensation for their time.

Descriptive statistics were generated for all variables with SPSS (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Cross tabulations for outcome variables by major demographic categories (age, gender, ethnicity, health literacy) were generated, using the Fisher’s exact t test to compare response rates between categories (α = 0.05).

RESULTS

Number of Prescription Medications Taken in Past Year

Sixty-two percent of the sample reported using 1 or more prescription medications in the past year. On average, participants reported taking 1.7 prescription medications; however, more than 25% of the sample reported taking 3 or more different prescription medications. Participants whose primary language was Spanish reported consuming fewer prescription medications (average = 1.1) than the overall sample (average = 1.7). None of the other demographic characteristics significantly influenced self-reports of medication prescriptions.

Medication Sharing

Of the 700 participants, 160 (22.9%) reported loaning their prescription medications to someone else. Table 1 ▶ presents the medication loaning and borrowing behaviors in total and across demographic groups. A total of 188 participants (26.9%) reported borrowing prescription medications from someone else. Interestingly, a higher percentage of those with high health literacy (31.2%) than of those with low health literacy (21.0%) indicated that they had taken a prescription medication that was not their own. A higher percentage of participants whose primary language was English (29.1%) than of those whose primary language was Spanish (17.9%) indicated that they had taken someone else’s prescription medication.

TABLE 1—

Self-Reported Sharing of Medications, Overall and by Participant Characteristics: United States, 2006

| Demographic Variables | Base Sample, No. (%) | Loaned Medicine, No. (%) | Borrowed Medicine, No. (%) | Both Loaned and Borrowed Medicine, No. (%) | Loaned but Did Not Borrow Medicine, No. (%) | Borrowed but Did Not Loan Medicine, No. (%) | Neither Loaned nor Borrowed Medicine, No. (%) |

| Total | 700 (100) | 160 (22.9) | 188 (26.9) | 112 (16.0) | 48 (6.9) | 76 (10.6) | 464 (66.3) |

| Health literacy | |||||||

| Low | 300 (100) | 57 (19.0) | 63 (21.0) | 40 (13.3) | 17 (5.7) | 23 (7.7) | 220a (73.0) |

| High | 400 (100) | 103 (25.8) | 125a (31.2) | 72 (18.0) | 31 (7.8) | 53 (13.2) | 244 (61.0) |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 190 (100) | 30 (15.8) | 49 (25.8) | 23 (12.1) | 7 (3.7) | 26 (13.7) | 134 (70.5) |

| Female | 510 (100) | 130a (25.5) | 139 (27.3) | 89 (17.5) | 41 (8.0) | 50 (9.8) | 330 (64.7) |

| Age, y | |||||||

| 12–17 | 138 (100) | 29 (21.0) | 31 (22.5) | 19 (3.8) | 10 (7.2) | 12 (8.7) | 97 (70.3) |

| 18–25 | 216 (100) | 47 (21.8) | 64 (29.6) | 36 (16.7) | 11 (5.1) | 28 (13.0) | 141 (65.3) |

| 26–35 | 176 (100) | 45 (25.6) | 50 (28.4) | 31 (17.6) | 14 (8.0) | 19 (10.8) | 112 (63.6) |

| 36–44 | 170 (100) | 39 (22.9) | 43 (25.3) | 26 (15.3) | 13 (7.6) | 17 (10.0) | 114 (67.1) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 338 (100) | 90b (26.6) | 102b (30.2) | 61 (18.0) | 29 (8.6) | 41 (12.1) | 207 (61.2) |

| African American | 170 (100) | 28 (16.5) | 40 (23.5) | 20 (11.8) | 8 (4.7) | 20 (11.8) | 122 (71.8) |

| Hispanic | 169 (100) | 35 (20.7) | 39 (23.1) | 26 (15.4) | 9 (5.3) | 13 (7.7) | 121 (71.6) |

| Other | 23 (100) | 7 (30.4) | 7 (30.4) | 5 (21.7) | 2 (8.7) | 2 (8.7) | 14 (60.9) |

| Home language | |||||||

| English | 520 (100) | 123 (23.7) | 151 (29.0) | 87 (16.7) | 36 (6.9) | 64 (12.3) | 333 (64.0) |

| Other | 180 (100) | 37 (20.6) | 37 (20.6) | 25 (13.9) | 12 (6.7) | 12 (6.7) | 131 (72.8) |

| Interview language | |||||||

| English | 560 (100) | 136 (24.3) | 163a (29.1) | 96 (17.1) | 40 (7.1.) | 67 (12.0) | 357 (63.8) |

| Other | 140 (100) | 24 (17.1) | 25 (17.9) | 16 (11.4) | 8 (5.7) | 9 (6.4) | 107a (76.4) |

Note. Response rates indicate that a participant would be more likely to loan or borrow a medication for the given hypothetical situation.

aResponse rate significantly higher than response rate for paired demographic variable for this hypothetical situation (P < .05).

bResponse rate significantly higher than response rate for African Americans for this hypothetical situation (P < .05).

Whereas 22.9% of the sample had loaned medicines and 26.9% had borrowed them, only 16.0% indicated they had done both. A large percentage (66.3%) had neither loaned nor borrowed medication.

The medications most frequently shared (loaned or borrowed; Table 2 ▶) were allergy medications (25.3%), followed by pain medications (21.9%) and antibiotics (20.6%). Higher percentages of Whites (23%) and Hispanics (26%) than of African Americans (13.5%) had shared pain medication. Higher percentages of females (24%) than of males (12%) had shared antibiotics. No other significant differences emerged.

TABLE 2—

Prescription Medications Shared by Study Participants: United States, 2006

| Prescription Medication | Had Loaned or Borrowed, % |

| Allergy medications (e.g., Allegra, Claritin) | 25.3 |

| Pain medications (e.g., Darvoset, oxycontin) | 21.9 |

| Antibiotics (e.g., amoxicillin, doxycycline, Bactrim/Septra) | 20.6 |

| Mood medications (e.g., Paxil, Zoloft, Valium, Ritalin) | 7.1 |

| Acne medication (e.g., Accutane) | 6.4 |

| Birth control pills | 5.3 |

| Other | 2.0 |

| None | 53.1 |

Note. Participants were asked, “Which, if any, of the following prescription medications have you loaned or borrowed?”

Medication Sharing in Different Scenarios

As shown in Table 3 ▶, when asked about hypothetical situations in which they would share (loan or borrow) medications, the participants most frequently indicated willingness to share when the medications came from a family member (39.4%), they had a prescription for a particular medication but ran out or did not have it with them (38.6%), or they had an emergency (37.9%).

TABLE 3—

Willingness of Participants to Share Medications Under Various Hypothetical Situations: United States, 2006

| Demographic Variables | Base Sample, No. (%) | Had the Same Problem as the Person, No. (%) | Had Prescription but Ran Out or Didn’t Have It With You, No. (%) | Got It From a Family Member, No. (%) | Wanted Something Strong for Pain or Headache, No. (%) | Wanted Something Strong for Pimples or Oily Skin, No. (%) | Wanted to Relax or Feel Good, No. (%) | Needed Something to Help You Sleep, No. (%) | Got It From Someone Who Knows About Medicine, No. (%) | Had an Emergency, No (%) | Had Hear About the Medicine From Ads or Commercials, No. (%) | Couldn’t Afford to Buy the Medicine but You Needed It, No. (%) | Had Leftover Medicine That Would Go to Waste, No. (%) | Had Some of Your Own Medicine That You Thought Could Help a Friend, No. (%) |

| Total | 700 (100) | 229 (32.7) | 270 (38.6) | 276 (39.4) | 223a (31.9) | 82 (11.7) | 114 (16.3) | 137 (19.6) | 175 (25.0) | 265 (37.9) | 105 (15.0) | 216 (30.9) | 130 (18.6) | 179 (25.6) |

| Health literacy | ||||||||||||||

| Low | 300 (100) | 88 (29.3) | 96 (32.0) | 105 (35.0) | 84 (28.0) | 37 (12.3) | 57 (19.0) | 56 (18.7) | 73 (24.3) | 104 (34.7) | 49 (16.3) | 86 (28.7) | 57 (19.0) | 76 (25.3) |

| High | 400 (100) | 141 (35.2) | 174b (43.5) | 171 (42.8) | 139 (34.8) | 45 (11.2) | 57 (14.2) | 81 (20.2) | 102 (25.5) | 161 (40.2) | 56 (14.0) | 130 (32.5) | 73 (18.2) | 103 (25.8) |

| Gender | ||||||||||||||

| Male | 190 (100) | 63 (33.2) | 67 (35.3) | 73 (38.4) | 62 (32.6) | 21 (11.1) | 30 (15.8) | 47 (24.7) | 40 (21.1) | 75 (39.5) | 33 (17.4) | 62 (32.6) | 33 (17.4) | 53 (27.9) |

| Female | 510 (100) | 166 (32.5) | 203 (39.8) | 203 (39.8) | 161 (31.6) | 61 (12.0) | 84 (16.5) | 90 (17.6) | 135 (26.5) | 190 (37.3) | 72 (14.1) | 154 (30.2) | 97 (19.0) | 126 (24.7) |

| Age, y | ||||||||||||||

| 12–17 | 138 (100) | 49 (35.5) | 57 (41.3) | 60 (43.5) | 40 (29.0) | 20 (14.5) | 26 (18.8) | 26 (18.8) | 47c (34.1) | 69c,d,e (50.0) | 17 (12.3) | 44 (31.9) | 18 (13.0) | 31 (22.5) |

| 18–25 | 216 (100) | 71 (32.9) | 85 (39.4) | 81 (37.5) | 67 (31.0) | 27 (12.5) | 45e (20.8) | 49 (22.7) | 41 (19.0) | 77 (35.6) | 34 (15.7) | 65 (30.1) | 41 (19.0) | 57 (26.4) |

| 26–35 | 176 (100) | 59 (33.5) | 65 (36.9) | 67 (38.1) | 67 (38.1) | 21 (11.9) | 26 (14.8) | 35 (19.9) | 45 (25.6) | 65 (36.9) | 30 (17.0) | 59 (33.5) | 37 (21.0) | 47 (26.7) |

| 36–44 | 170 (100) | 50 (29.4) | 63 (37.1) | 68 (40.0) | 49 (28.8) | 14 (8.2) | 17 (10.0) | 27 (15.9) | 42 (24.7) | 54 (31.8) | 24 (14.1) | 48 (28.2) | 34 (20.0) | 44 (25.6) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||||

| White | 338 (100) | 117 (34.6) | 147a (43.5) | 146 (43.2) | 105 (31.1) | 33 (9.8) | 51 (15.1) | 70 (20.7) | 87 (25.7) | 131 (38.8) | 40 (11.8) | 106 (31.4) | 65 (19.2) | 83 (24.6) |

| African | 170 (100) | 47 (27.6) | 53 (31.2) | 55 (32.4) | 38 (22.4) | 18 (10.6) | 22 (12.9) | 24 (14.1) | 35 (20.6) | 61 (35.9) | 21 (12.4) | 45 (26.5) | 22 (12.9) | 35 (20.6) |

| American | ||||||||||||||

| Hispanic | 169 (100) | 54 (32.0) | 61 (36.1) | 67 (39.6) | 71a (42.0) | 26 (15.4) | 35 (20.7) | 36 (21.3) | 46 (27.2) | 65 (38.5) | 39a,f (23.1) | 55 (32.5) | 39 (23.1) | 55 (32.5) |

| Other | 23 (100) | 11 (47.8) | 9 (39.1) | 8 (34.8) | 9 (39.1) | 5 (21.7) | 6 (26.1) | 7 (30.4) | 7 (30.4) | 8 (34.8) | 5 (21.7) | 10 (43.5) | 4 (17.4) | 6 (26.1) |

| Home language | ||||||||||||||

| English | 520 (100) | 173 (33.3) | 211 (40.6) | 207 (39.8) | 152 (29.2) | 54 (10.4) | 75 (14.4) | 103 (19.8) | 125 (24.0) | 196 (37.7) | 61 (11.7) | 153 (29.4) | 81 (15.6) | 115 (22.1) |

| Other | 180 (100) | 56 (31.1) | 59 (32.8) | 69 (38.3) | 71 (39.4) | 28 (15.6) | 39 (21.7) | 34 (18.9) | 50 (27.8) | 69 (38.3) | 44b,d (24.4) | 63 (35.0) | 49b (27.2) | 64b (35.6) |

| Interview language | ||||||||||||||

| English | 560 (100) | 186 (33.2) | 226 (40.4) | 224 (40.0) | 173 (30.9) | 66 (11.8) | 87 (15.5) | 113 (20.2) | 141 (25.2) | 218 (38.9) | 73 (13.0) | 169 (30.2) | 95 (17.0) | 132 (23.6) |

| Other | 140 (100) | 43 (30.7) | 44 (31.4) | 52 (37.1) | 50 (35.7) | 16 (11.4) | 27 (19.3) | 24 (17.1) | 34 (24.3) | 47 (33.6) | 32 (22.9) | 47 (33.6) | 35 (25.0) | 47 (33.6) |

Note. Response rates indicate that a participant would be more likely to loan or borrow a medication for the given hypothetical situation.

aResponse rate significantly higher than response rate for African Americans for this hypothetical situation (P < .05).

bResponse rate significantly higher than response rate for paired demographic variable for this hypothetical situation (P < .05).

cResponse rate significantly higher than response rate for 18–25 year-olds for this hypothetical situation(P < .05).

dResponse rate significantly higher than response rate for Total for this hypothetical situation (P < .05).

eResponse rate significantly higher than response rate for 36–40 year-olds for this hypothetical situation (P < .05).

fResponse rate significantly higher than response rate for Whites for this hypothetical situation (P < .05).

Age was a factor in 3 scenarios. Fifty percent of adolescents (aged 12–17 years) reported willingness to share in emergency situations; this willingness was significantly lower (35.6%) among those aged 18 to 25 years and was only 31.8% among those aged 36 to 44 years. A higher percentage of adolescents (34.1%) than of those aged 18 to 25 years (19.0%) reported being willing to use someone else’s medication when they believed they were getting the substance from “someone who knew something about medications.” Finally, a higher percentage of those aged 18 to 25 years (20.8%) than of those aged 36 to 44 years (10.0%) indicated they would borrow prescription medications to relax or feel good.

When they had “heard a lot about the medicine from ads or commercials,” a higher percentage of participants whose primary language was Spanish (24.4%) than of those whose primary language was English (11.7%) expressed a willingness to share, as did a higher percentage of Hispanics (23.1%) than of African Americans (12.4%) or Whites (11.8%).

When they “wanted something strong for pain or headache,” a higher percentage of His-panics (42.0%) than of African Americans (22.4%) would share medications. A higher percentage of Whites (43.5%) than of African Americans (31.2%) would borrow someone else’s medication when they already had a prescription for that medication but had run out or did not have it with them; a higher percentage of those with high health literacy (43.5%) than of those with low health literacy (32.0%) also would share under these circumstances.

Other Situations in Which Sharing Might Occur

Twenty-seven participants (3.9%) indicated they could think of other situations in which they would loan or borrow prescription medication. Some of these additional situations—such as “If they were really, really sick,” “Only if a doctor said it was okay to do so,” and “Antibiotics with my husband if I thought he needed it for a cold”—illustrate well-intended medication sharing, where people are trying to help others. By contrast, responses such as “If I was offered money” and “For money” suggest less-well-intentioned, opportunistic behaviors.

DISCUSSION

We present a framework for considering the consequences of medication sharing and broadly describe this social phenomenon, which is largely neglected in the medical and public health literature. In terms of the medication sharing impact framework, the results suggest that people are engaging in loaning (22.9%) and borrowing (26.9%) behaviors relatively frequently, that rates of hypothetical situations in which they might consider sharing are higher still, and that the types of sharing that are occurring probably entail each of the consequences delineated in the framework. For example, 21.9% of the sample indicated they had shared pain medications, and 7% indicated they had shared mood-altering medications. These findings support previous research on the prevalence of illicit use of certain prescription medications.

A little more than one fifth of the sample (20.6%) indicated they had shared antibiotics, a finding that suggests that such sharing is fairly widespread and may exacerbate pathogenic resistance to antibiotics, which is a public health concern. Of every 4 participants, 1 would share medications if they had medication that they thought could help a friend, and nearly 1 out of 5 would if “they had leftover medicine that would be wasted.” Both of these sharing behaviors could lead to reduced care seeking, and both were notably higher among those who spoke Spanish in their homes. Regarding side effects, 6.4% of the sample indicated they had shared acne medication, a behavior that places individuals who are or may become pregnant at risk for exposure to teratogenic pharmaceuticals.

Limitations

Although well distributed across a variety of demographic characteristics, the sample was relatively small. As a result, its representativeness across the diverse demographic backgrounds is of concern. The study provides some evidence that medication sharing varies by individual characteristics; however, the percentages of participants manifesting each characteristic and the number of comparative analyses conducted indicate that the comparison data should be considered exploratory. Finally, participant responses may have been influenced by the belief that medication sharing is an illicit or illegal behavior. If responses were inhibited by this perception, the current data underrepresent the prevalence of prescription medication sharing. Future work should validate and extend these results with larger samples; instruments that not only assess the sharing behaviors but also directly assess the consequences would further enhance the results.

Conclusions

Prescription medication sharing can lead to adverse outcomes at the societal level through such consequences as ineffective use of the health system and increased antibiotic resistance, and at the personal level through such effects as decreased treatment efficacy and increased risk for side effects and drug interactions. Our proposed medication sharing impact framework sets forth and organizes the outcomes and risks associated with medication sharing. Our findings indicate that approximately 1 of every 4 participants shared medication, and diverse classes of medication were shared. This suggests that a large number of individuals are at risk for loss of warnings and instructions, reduced likelihood of appropriate use and compliance, and numerous related consequences, including reduced care seeking, increased perceptions of ineffective treatment, increased antibiotic resistance, and increased risk of side effects.

Acknowledgments

The research discussed in this report was supported by the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities (NCBDDD; grants 1R43DD00001-01 and 1R44DD00001-01), a part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Note. The article’s contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCBDDD or CDC.

Human Participant Protection The research reported was approved by the institutional review board of The Academic Edge Inc.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors R. C. Goldsworthy developed the framework, originated and managed the study, assisted with data analysis, and wrote the article. N. C. Schwartz assisted with the study analysis and interpretation and reviewed drafts of the article. C. B. Mayhorn analyzed data and cowrote the “Results” section.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed]

- 2.Daniel KL, Honein MA, Moore CA. Sharing prescription medication among teenage girls: potential danger to unplanned/undiagnosed pregnancies. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5 Pt 2):1167–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyd CJ, McCabe SE, Cranford JA, Young A. Adolescents’ motivations to abuse prescription medications. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2472–2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyd CJ, McCabe SE, Cranford JA, Young A. Prescription drug abuse and diversion among adolescents in a southeast Michigan school district. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:276–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forgione DA, Neuenschwander P, Vermeer TE. Diversion of prescription drugs to the black market: what the states are doing to curb the tide. J Health Care Finance. 2001;27:65–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meadows M. Prescription drug use and abuse. FDA Consum. 2001;35:18–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meadows M. Prescription drug abuse. FDA Consum. 2003;37:36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simoni-Wastila L, Ritter G, Strickler G. Gender and other factors associated with the nonmedical use of abusable prescription drugs. Subst Use Misuse. 2004; 39:1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCabe SE, Boyd CJ, Young A. Medical and non-medical use of prescription drugs among secondary school students. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:76–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCabe SE, Boyd CJ. Sources of prescription drugs for illicit use. Addict Behav. 2005;30: 1342–1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCabe SE, Teter CJ, Boyd CJ. Medical use, illicit use and diversion of prescription stimulant medication. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2006;38:43–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White BP, Becker-Blease KA, Grace-Bishop K. Stimulant medication use, misuse, and abuse in an undergraduate and graduate student sample. J Am Coll Health. 2006;54:261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldsworthy R, Kaplan B. Warning symbol development: a case study on teratogen symbol design and evaluation. In: Wogalter MS, ed. Handbook of Warnings. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2006: 739–754.

- 14.Roche Laboratories. System to manage Accutane related teratogenicity (S.M.A.R.T.): guide to best practices. 2001. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/infopage/accutane. Accessed January 10, 2006.

- 15.Huott MA, Storrow AB. A survey of adolescents’ knowledge regarding toxicity of over-the-counter medications. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4:214–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Census Bureau. Projections of the Resident Population by Race, Hispanic Origin, and Nativity: Middle Series. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2002.

- 17.Davis TC, Michielutte R, Askov EN, Williams MV, Weiss BD. Practical assessment of adult literacy in health care. Health Educ Behav. 1998;25:613–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nabors LA, Lehmkuhl HD, Parkins IS, Drury AM. Reading about over-the-counter medications. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 2004;27:297–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bass PF III, Wilson JF, Griffith CH. A shortened instrument for literacy screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:1036–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med. 1993;25:391–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF, et al. Low literacy impairs comprehension of prescription drug warning labels. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:847–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]