Abstract

Molecular targeting for apoptosis induction is being developed for better treatment of cancer. Down-regulation of 15-lipoxygenase-1 (15-LOX-1) is linked to colorectal tumorigenesis. Re-expression of 15-LOX-1 in cancer cells by pharmaceutical agents induces apoptosis. Antitumorigenic agents can also induce apoptosis via other molecular targets. Whether restoring 15-LOX-1 expression in cancer cells is therapeutically sufficient to inhibit colonic tumorigenesis remains unknown. We tested this question by using an adenoviral delivery system to express 15-LOX-1 in in vitro and in vivo models of colon cancer. We found that a) the adenoviral vector 5/3 fiber modification enhanced 15-LOX-1 gene transduction in various colorectal cancer cell lines, b) the adenoviral vector delivery restored 15-LOX-1 expression and enzymatic activity to therapeutic levels in colon cancer cell lines, and c) 15-LOX-1 expression down-regulated the expression of the antiapoptotic proteins XIAP and BcL-XL, activated caspase-3, triggered apoptosis, and inhibited cancer cell survival in vitro and the growth of colon cancer xenografts in vivo. Thus, selective molecular targeting of 15-LOX-1 expression is sufficient to re-establish apoptosis in colon cancer cells and inhibit tumorigenesis. These data provide the rationale for further development of therapeutic strategies to molecularly target 15-LOX-1 for treating colonic tumorigenesis.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer ranks second as a cause of cancer deaths in the United States, and despite recent improvement in therapeutic interventions, a significant proportion of patients continue to die because of the disease [1]. Therefore, new strategies to treat colorectal cancers are needed.

The marked improvement in our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of tumorigenesis has led to the emergence of the field of molecular therapeutic targeting, which holds the promise of developing more effective and better-tolerated anticancer therapies [2]. 15-Lipoxygenase-1 (15-LOX-1) is the rate limiting–step enzyme for the conversion of linoleic acid to 13-S-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid [3]. 15-LOX-1 contributes to terminal cell differentiation and the control of the inflammatory response [4]. It is down-regulated in human colonic [5–7], esophageal [8], breast [9], and pancreatic cancers [10]. 15-LOX-1 is an attractive molecular target, given that its re-expression by pharmaceutical agents (e.g., celecoxib, suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, sodium butyrate [NaBT]) induces apoptosis in cancer cells and inhibits tumorigenesis [11–15]. These drugs, however, also modulate various other molecular targets to trigger apoptosis and inhibit tumorigenesis [16, 17]. Therefore, whether the specific molecular targeting of 15-LOX-1 in colorectal cancer cells can be used to inhibit tumorigenesis is unknown.

Molecular targeting of 15-LOX-1 would require the restoration of its lost gene expression in cancer cells. One approach to specifically restore that lost expression is via an adenoviral delivery system [18–20]. Human adenovirus type 5 (Ad-5) is commonly used as a viral transduction vehicle because it expresses genes efficiently in both proliferating and quiescent cells, can easily be produced in high titers, and lacks the ability to integrate into the host genome, which confers relative safety [18]. We have therefore selected an Ad-5 vector for examining whether 15-LOX-1 can be molecularly targeted to inhibit colonic tumorigenesis.

The Ad-5 vector infectivity of human cells, however, is dependent on binding of the adenoviral fiber knob to the coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR) [21]. Tumor cells, including colon cancer cells, often have low CAR expression levels, limiting their susceptibility to adenoviral vectors [22, 23]. The chimeric adenoviral 5/3 fiber (Ad-5/3), which is generated by replacing the Ad-5 fiber knob with that of Ad-3 [21], allows adenoviral vectors to bind the serotype 3 receptor, which is expressed more commonly than CAR is on cancer cells [24]. This approach has improved gene transduction in preclinical models of ovarian and prostatic tumor cells [21, 24]. We therefore tested whether the Ad-5/3 modification can improve adenoviral vector expression of 15-LOX-1 in human colon cancer cells.

Gene expression via adenoviral vectors can be targeted to cancer cells to reduce the risk of toxicity by using promoters that are selectively activated in cancer but not normal cells. Telomerase, a DNA polymerase that replicates telomeres (chromosomal ends), is expressed in most human cancers but not in normal human somatic cells [25]. hTERT, the essential catalytic unit in the telomerase nucleoprotein complex, is overexpressed in human colorectal cancer [25, 26]. The hTERT promoter is differentially activated in cancer but not in normal cells [27, 28] and has been used to selectively transduce genes in tumor cells [29–31]. Therefore, we used the hTERT promoter to selectively target 15-LOX-1 expression via adenoviral vector delivery to human colon cancer cells and to examine the efficacy of 15-LOX-1 molecular targeting against colon cancer in vitro and in in vivo preclinical models.

RESULTS

Ad-5/3 fiber modification enhances gene transduction to express 15-LOX-1

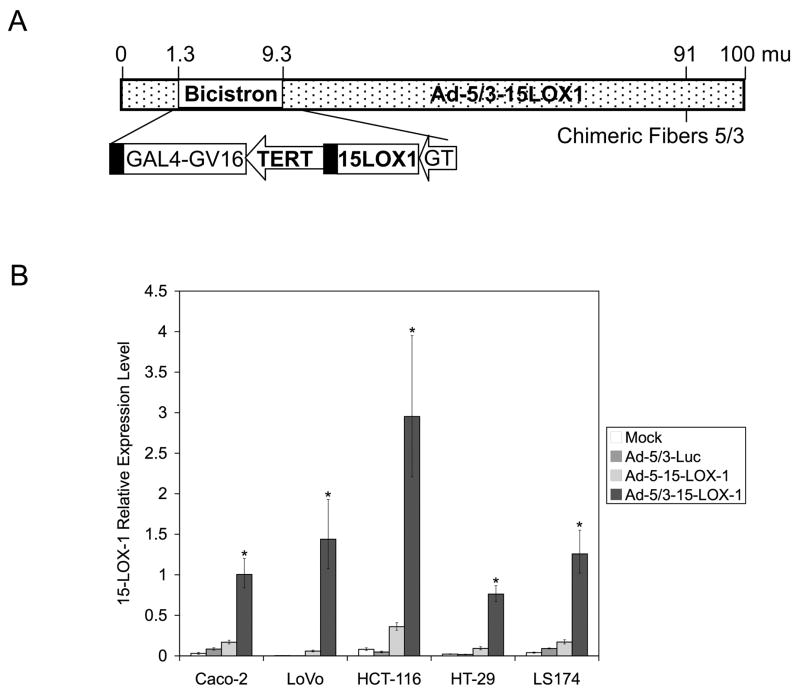

The recombinant adenoviral vector that expresses 15-LOX-1 and the chimeric adenoviral fiber 5/3 (i.e., Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1; Figure 1a) was constructed and purified as described in the Materials and Methods section. Adenoviral vector gene transduction, as measured by 15-LOX-1 expression, was 5.95–24.40 times higher in colon cancer cell lines transfected with the Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1–modified vector than it was in those transfected with the Ad-5-15-LOX-1 unmodified vector (P < 0.0001 for all comparisons; Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

The effects of adenoviral 5/3 fiber modification on 15-LOX-1 transduction. (a) Schematic representation of the modified adenoviral vector with 5/3 chimeric fiber. (b) Transduction of 15-LOX-1 via modified Ad-5/3 vector vs. unmodified Ad-5 vector. Caco-2, LoVo, HCT-116, HT-29, and LS174 colon cancer cells were transfected with 500 viral particles per cell of unmodified adenoviral vector that expresses 15-LOX-1 (Ad-5-15-LOX-1), the modified Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1, and the modified Ad-5/3-luciferase (Ad-5/3-Luc), or were left untransfected (Mock). Cells were harvested, and total RNA was extracted and processed for 15-LOX-1 measurements by quantitative real-time PCR. The relative expression levels were calculated as the values relative to that of the calibrator sample (Caco-2 cells treated with NaBT for 48 hours). Values shown are the means ± SDs of triplicate experiments. *P < 0.0001, Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 versus Ad-5/3-Luc, Ad-5-15-LOX-1, and Mock.

Adenoviral vector reconstitutes expression and enzymatic activity of 15-LOX-1 in colon cancer cells

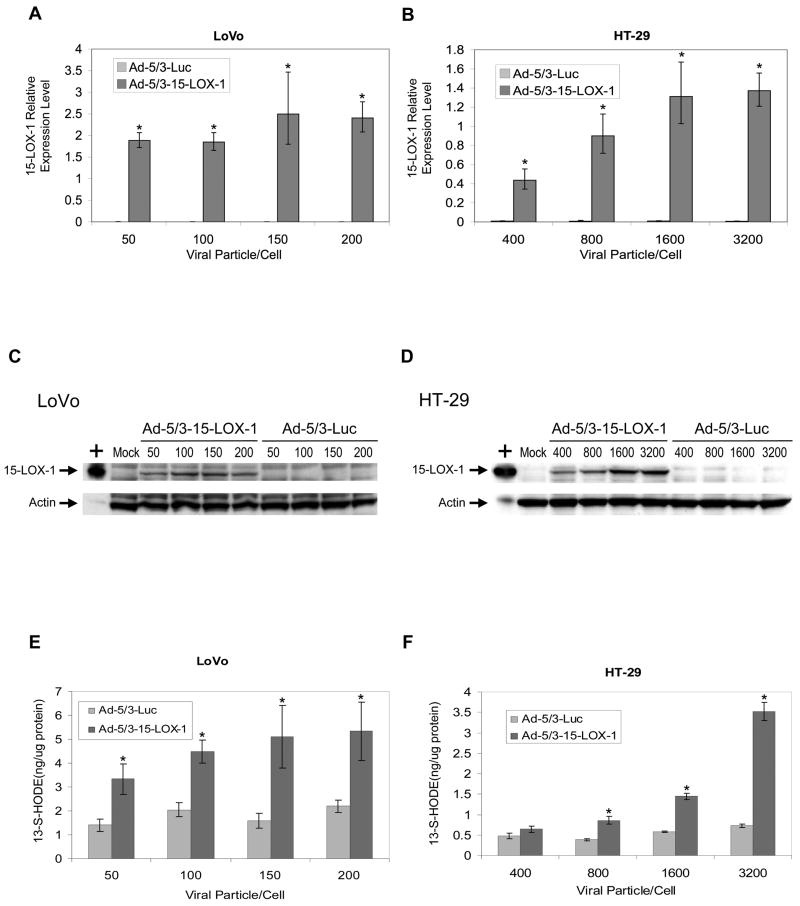

The Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 vector markedly increased 15-LOX-1 mRNA levels for the various concentrations tested in LoVo, HT-29, and HCT-116 cells, whereas Ad-5/3-Luc control vector transfection failed to increase them using identical viral particle concentrations (P < 0.0001 for all comparisons between Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 and Ad-5/3-Luc; Figure 2a, Figure 2b, and Supplementary Figure S1a). Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 vector-induced expression of 15-LOX-1 mRNA reached levels equal to those induced by NaBT in Caco-2 cells at 50, 800, and 100 viral particles per cell for LoVo, HT-29, and HCT-116 cells, respectively. The slopes of the linear regression of 15-LOX-1 relative expression levels on concentration were significantly different for Ad-5/3-Luc and Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 (P = 0.0012 for LoVo, P = 0.0005 for HT-29, and P < 0.0001 for HCT-116; Figure 2a, Figure 2b, and Supplementary Figure S1a). With Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1, 15-LOX-1 relative expression levels increased with increasing concentrations, whereas with Ad-5/3-Luc, 15-LOX-1 relative expression levels were flat across concentrations. Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 vector adenoviral transfection successfully induced 15-LOX-1 protein expression in LoVo, HCT-116, and HT-29 cells in a concentration-dependent manner, whereas Ad-5/3-Luc control vector transfection had no effect on 15-LOX-1 protein expression (Figure 2c, Figure 2d, and Supplementary Figure S1b). In addition, 15-LOX-1 expression significantly increased the formation of 13-S-HODE (the main 15-LOX-1 product) in LoVo, HT-29, and HCT-116 cells at 50, 800, and 100 viral particles per cell, respectively (P < 0.0001 for all stated comparisons between Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 and Ad-5/3-Luc; Figure 2e, Figure 2f, and Supplementary Figure S1c), the same concentrations that induced 15-LOX-1 mRNA expression levels equal to those induced by NaBT in Caco-2 cells. Paralleling our findings with respect to 15-LOX-1 mRNA expression, we found that with Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1, 13-S-HODE levels increased with increasing concentrations, whereas with Ad-5/3-Luc, 13-S-HODE levels were flat across concentrations (P = 0.0021 for LoVo and P < 0.0001 for HT-29 and HCT-116 cells).

Figure 2.

15-LOX-1 transduction by adenoviral vector transfection in colon cancer cells. (a and b) 15-LOX-1 mRNA expression by adenoviral transfection into colon cancer cells. LoVo (a) and HT-29 (b) colon cancer cell lines were transfected with either the modified Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 vector or with the control vector, Ad-5/3-luciferase (Ad-5/3-Luc). Cells were harvested 24 hours after transfection, and 15-LOX-1 mRNA was measured with real-time PCR. The relative expression levels were calculated as the values relative to that of a calibrator sample (Caco-2 cells treated with NaBT for 48 hours). Values shown are the means ± SDs of triplicate measurements. *P < 0.0001, Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 versus Ad-5/3-Luc. (c and d) 15-LOX-1 protein expression by adenoviral transfection into colon cancer cells. LoVo (c) and HT-29 (d) cells were transfected with either Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 or Ad-5/3-Luc, and cells were harvested 48 hours later and processed for 15-LOX-1 protein expression by Western blotting. + represents a positive control for 15-LOX-1. (e and f) Enzymatic activity of the 15-LOX-1 protein expressed by Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 into colon cancer cells. LoVo (e) and HT-29 (f) cells were transfected with either Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 or Ad-5/3-Luc, and cells were harvested 48 hours later and processed for 13-S-HODE, the major enzymatic product of 15-LOX-1. Values shown are the means ± SDs of triplicate measurements. *P < 0.0001 Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 versus Ad-5/3-Luc.

15-LOX-1 expression inhibits cell growth and induces apoptosis in vitro

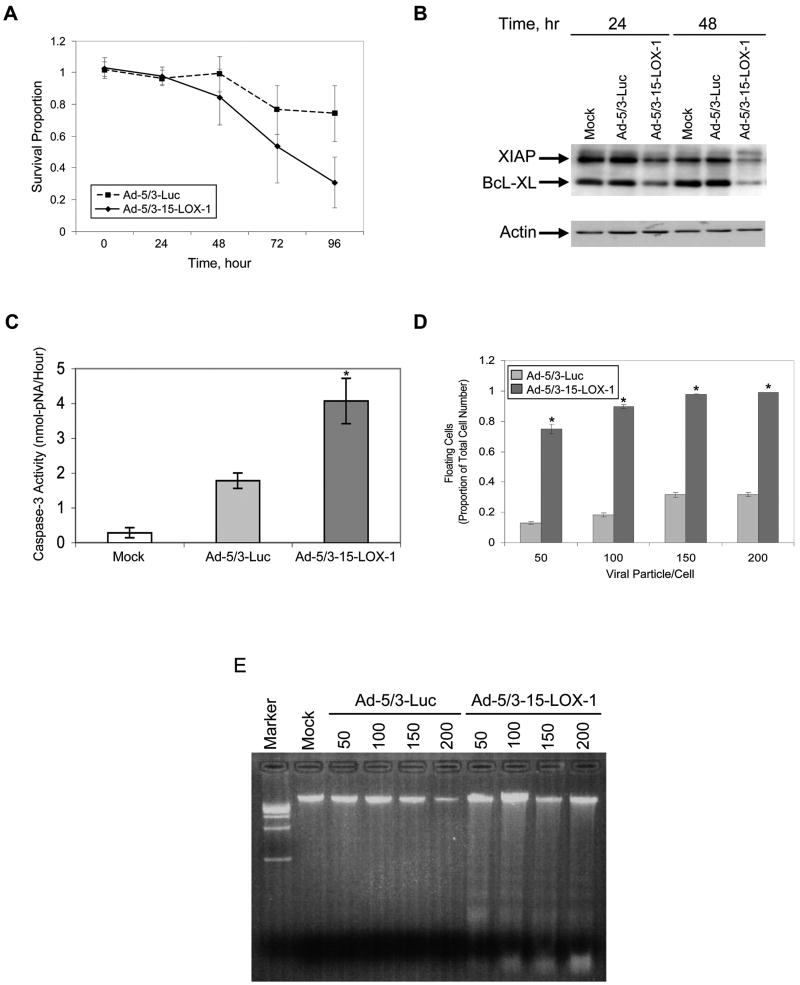

15-LOX-1 expression inhibited LoVo, HCT-116, and HT-29 cell growth in a time-dependent manner that became statistically significantly different between 72 and 96 hours after transfection with Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 (P < 0.0001 for all cell lines compared with the control vector, Ad-5/3-Luc; Figure 3a and Supplementary Figures S2a and S2b). 15-LOX-1 expression down-regulated the expression of both X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) and BcL-XL at 48 hours in LoVo, HT-29, and HCT-116 cell lines (Figure 3b and Supplementary Figures S2c and S2d). Caspase-3 activation was also significantly increased in LoVo, HT-29, and HCT-116 cells when 15-LOX-1 was expressed by Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 transfection compared with its activation in cells transfected with Ad-5/3-Luc or in nontransfected cells (P < 0.0001 for all comparisons; Figure 3c and Supplementary Figures S2e and S2f). Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 transfection increased the ratio of floating to total cells at 72 hours (P < 0.0001 for all comparisons; Figure 3d and Supplementary Figures S2g and S2h). Finally, Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 transfection induced a DNA-laddering pattern typical of apoptosis in LoVo, HT-29, and HCT-116 cells (Figure 3e and Supplementary Figures S2i and S2j).

Figure 3.

Effects of 15-LOX-1 expression by adenoviral vector on cell survival and apoptosis induction in cancer cells. (a) Kinetics of effects of 15-LOX-1 expression on colon cancer cell survival. HCT-116 colon cancer cell lines were transfected with either Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 or with the control vector Ad-5/3-luciferase (Ad-5/3-Luc) at a concentration of 150 viral particles/cell. Cell survival was measured using sulforhodamine B at 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours. Results are presented as the ratios of Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1– or Ad-5/3-Luc–transfected cells to untransfected cells (survival proportion). Values shown are the means ± SDs of six replicate experiments. (be) Effects of 15-LOX-1 expression via adenoviral vector on apoptosis in colon cancer cells. (b) Effects of 15-LOX-1 expression on XIAP and BcL-XL expression in colon cancer cells. HCT-116 cells were transfected with either Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 or Ad-5/3-Luc (100 viral particles/cell), and cells were harvested 24 and 48 hours later and processed for XIAP and BcL-XL expression by Western blotting. (c) Effect of 15-LOX-1 expression on apoptosis, as measured by level of caspase-3 activity. HCT-116 cells were transfected with Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 or Ad-5/3-Luc (100 viral particles/cell). Cells were harvested 48 hours later and processed for measuring caspase-3 enzymatic activity. Values shown are the means ± SDs of triplicate experiments. *P < 0.0001 Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 versus Ad-5/3-Luc and Mock. (d) Effect of 15-LOX-1 expression on apoptosis measured as floating cell ratio. HCT-116 cells were transfected with Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 or Ad-5/3-Luc in the indicated concentrations, and the floating and attached cells were counted 72 hours later. The proportion of floating cells to total cells was calculated as a measure of apoptosis. Values shown are the means ± SDs of triplicate experiments. *P < 0.0001 Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 versus Ad-5/3-Luc. (e) Effect of 15-LOX-1 expression on apoptosis as measured by DNA laddering. HCT-116 cells were transfected with Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 or Ad-5/3-Luc, and cells were harvested 72 hours later and processed for DNA laddering assays. The lanes are numbered with the concentration of viral particles/cell for each vector. The DNA laddering pattern typical of apoptosis was observed for Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 in various concentrations but not for Ad-5/3-Luc.

Safety and efficacy of subcutaneous injections of Ad-15-LOX-1 into colon cancer xenografts in vivo

Liver function studies performed 9, 22, and 37 days after the start of adenoviral vector injection revealed no significant differences between the Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) groups in the levels of aspartate aminotransferase (P = 0.41), alanine aminotransferase (P = 0.08), or alkaline phosphatase (P = 0.94). Necropsies and histologic examinations of the brain, liver, kidneys, heart, spleen, pancreas, adrenal glands, and gastrointestinal tract of mice that were killed between 13 and 36 days after the last injection of the adenoviral vectors (Ad-5/3-Luc or Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1) or PBS revealed a higher frequency of splenic extramedullary hematopoietic hyperplasia and follicular lymphoid hyperplasia in the Ad-5/3-Luc and Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 groups than in the PBS group. No other consistent lesions occurred in the animals from any particular group.

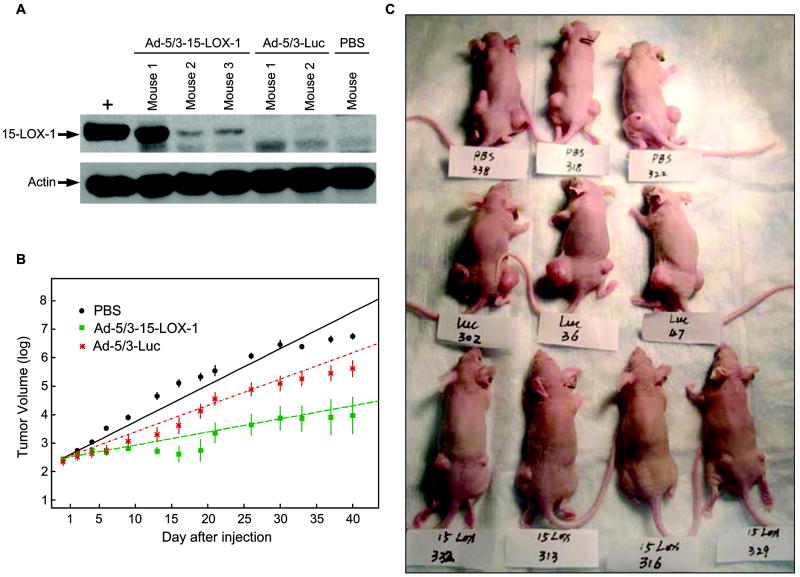

The injections of the Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 adenoviral vector into LoVo colon cancer xenografts induced the expression of 15-LOX-1, whereas Ad-5/3-Luc and PBS injections resulted in no 15-LOX-1 expression (Figure 4a). The Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 injections markedly inhibited the growth of subcutaneously transplanted xenografts of LoVo cells in nude mice compared with that in mice injected with the Ad-5/3-Luc control vector (P = 0.0001) or PBS (P < 0.0001) (Figure 4b). Finally, complete regression of the tumor was observed in 5 of 24 xenografts (21%) in the Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 group but not in the Ad-5/3-Luc-5/3 control vector or PBS control groups (Figure 4c).

Figure 4.

15-LOX-1 expression via an adenoviral vector inhibits colonic tumorigenesis in vivo. (a) 15-LOX-1 expression via the Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 adenoviral vector into LoVo colon cancer xenografts. Nude mice with LoVo colon cancer cell xenografts were killed 3 days after injection of Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 adenoviral vector (Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1), Ad-5/3-luciferase adenoviral vector (Ad-5/3-Luc), or PBS. Xenografts were harvested and then processed for 15-LOX-1 Western blotting. + represents a positive control for 15-LOX-1. (b) Effects of 15-LOX-1 expression on growth of LoVo xenografts in nude mice. Xenografts of LoVo colon cancer cells in 35 mice divided into three groups were injected with PBS (control) or Ad-5/3-Luc or Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 adenoviral vectors. A growth-curve model was used to fit the animal data and assess whether 15-LOX-1 expression affected tumor growth using a log-linear mixed-effect model with treatments, time after injection, and their interaction as the fixed effects and the animal as a random effect. Values shown are the means ± SEs. Repeated experiments showed similar results. (c) This photograph of representative mice treated as described in panel b was taken on day 44 from the time of adenoviral vectors or PBS injection. Mice are labeled PBS (control), Luc (Ad-5/3-Luc adenoviral vector), and 15-LOX (Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 adenoviral vector). Complete xenograft regression was noted in only the Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 adenoviral vector group (in 5 of 24 xenografts).

DISCUSSION

This study showed that the specific molecular targeting of 15-LOX-1 in colon cancer cells via an adenoviral vector gene delivery system was sufficient to down-regulate the expression of the antiapoptotic proteins XIAP and BcL-XL, induce apoptosis, and inhibit colon cancer cell survival in vitro and in vivo.

The adenoviral vector delivery system with the 5/3 viral fiber modification successfully induced therapeutic levels of 15-LOX-1 expression and enzymatic activity in the tested colon cancer cells. 15-LOX-1 expression levels in LoVo, HCT-116, and HT-29 colon cancer cell lines via the 5/3 modified adenoviral vector delivery system reached levels comparable to the ones attained by the histone deacetylase inhibitor (HDACI) NaBT to induce apoptosis in colon cancer cells in vitro [15]. The enzymatic activity of 15-LOX-1 protein, as measured by 13-S-HODE formation, was also similar to that achieved with NaBT in colon cancer cells during apoptosis induction. These findings demonstrated the ability of the adenoviral gene delivery system to induce 15-LOX-1 expression and enzymatic activity similarly to pharmaceutical agents (e.g., NaBT) but with the advantage of being more specifically targeted to 15-LOX-1 than pharmaceutical agents are. The Ad-5/3 viral fiber modification markedly improved 15-LOX-1 gene delivery via the adenoviral vector to colon cancer cells, compared with the variable and often low gene-transduction efficiency achieved with the non-modified Ad-5 vectors reported previously [32] and in this article. These findings are in agreement with what has been observed in ovarian and prostatic cancer cells [21, 24]. Thus, the Ad-5/3 viral fiber modification appears to improve gene delivery via adenoviral viral vectors in various experimental models of epithelial cancers.

The specific molecular targeting of 15-LOX-1 was sufficient to inhibit colon cancer survival in vitro. Reconstituting 15-LOX-1 expression and activity to within the therapeutic range as achieved via the adenoviral expression system inhibited colon cancer cell survival in a time-dependent manner, which corresponds to previously reported time points for apoptosis induction in colon cancer cells by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and HDACIs [11, 13, 33]. These findings established the adequacy of 15-LOX-1 molecular targeting in inducing a therapeutic response in timely manner in colon cancer cells in vitro.

The activation of apoptosis by 15-LOX-1 involved down-regulation of the antiapoptotic proteins BcL-XL and XIAP. This is a new and important mechanism for apoptosis induction by 15-LOX-1. The ability of cancer cells to evade apoptosis is important for tumorigenesis and the resistance to anticancer treatment [34]. BcL-XL, a proto-oncogene Bcl-2–related protein, and XIAP, a member of the inhibitor of apoptosis protein family, contribute significantly to cancer cells resistance to apoptosis [35, 36]. HDACIs restore 15-LOX-1 expression [13, 15] and also down-regulate both BcL-XL [37] and XIAP [38] during apoptosis induction. Whether these effects of HDACIs are mechanistically linked to therapeutically induce apoptosis has been unreported until now, to the best of our knowledge. Our new findings indicate that this link exists by demonstrating that 15-LOX-1 down-regulates XIAP and BcL-XL as a mechanism of triggering apoptosis. Other mechanisms that have been reported previously and in this article for 15-LOX-1 inhibition of cancer cells survival and induction of apoptosis include p53 phosphorylation [39], up-regulation of the pro-apoptotic protein BAX [40], and activation of caspase-3 [13, 32]. In the current study, however, 15-LOX-1 suppressed cell survival and induced apoptosis in HT-29 cells, which have a p53 mutation [41]. These findings indicate that induction of apoptosis by 15-LOX-1 can occur via p53-independent mechanisms. Nevertheless, our current findings further demonstrated that 15-LOX-1 induced apoptosis through multiple mechanisms, including ones that can potentially overcome cancer cells resistance to apoptosis via XIAP and BcL-XL.

Specific molecular targeting of 15-LOX-1 was sufficient to inhibit colonic tumorigenesis in vivo. The expression of 15-LOX-1 via the adenoviral delivery system in human colon cancer xenografts significantly inhibited tumor growth in vivo. 15-LOX-1 expression via an Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 vector in these studies was associated with no significant toxicity. Of note, the therapeutic response was successful in inducing complete tumor regression in 20% of the injected xenografts. However, this therapeutic response is likely to have been limited by the inability of subcutaneous administration route and the nonreplicating adenoviral vector to provide homogeneous gene delivery distribution into cancer cells within the xenografts, as evidenced by the variable 15-LOX-1 expression levels among the xenografts.

The data generated from our current in vivo model serve as the first demonstration of proof of principle for the feasibility of molecularly targeting of 15-LOX-1 in vivo. This model has certain limitations, however. First, the experiments were done in immunocompromised mice, thus the effects of the immune system on adenoviral clearance on vector-mediated gene transfer cannot be ascertained in the current system. Future studies in immunocompetent animals will be needed to examine this issue further. And second, the subcutaneus delivery method has limited applicability to targeting deep organ metastases as commonly seen in metastatic colon cancer. Future testing of the 15-LOX-1 molecular targeting strategy in more complex and representative preclinical models of human colon cancer metastases will be needed to develop this approach further. One such preclinical model would involve gene delivery into hepatic metastases via systemic intravenous administration of adenoviral vectors [42–44]. Hepatic metastases are a common cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with colorectal cancers [45, 46], and future testing of molecularly targeting 15-LOX-1 to colon cancer hepatic metastases through systemic administration of adenoviral vectors would be helpful to evaluate the potential clinical utility of this approach.

In conclusion, our current results demonstrate the feasibility of molecularly targeting 15-LOX-1 to inhibit colonic tumorigenesis both in vitro and in vivo and the ability of 15-LOX-1 to activate apoptosis via multiple downstream targets, including down-regulation of the antiapoptotic proteins XIAP and BcL-XL. These data provide the rationale for further studies to identify new and improved methods—via pharmaceutical or better gene-delivery approaches—to restore 15-LOX-1 expression in human cancer as a molecularly targeted approach to treat tumorigenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

We obtained the rabbit polyclonal antiserum to recombinant human 15-LOX-1 and 15-LOX-1 expression vector as described previously [12]. Monoclonal antibodies against the XIAP and BcL-XL antiapoptotic proteins were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). The following human colon cancer cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) or as described previously [12]: Caco-2, LoVo, HCT-116, HT-29, and LS174. 13-S-HODE enzyme immunoassay kits were purchased from Assay Designs Inc. (Ann Arbor, MI). Other reagents, molecular-grade solvents, and chemicals were obtained from commercial manufacturers or as specified.

Cell cultures

All cells were cultured in RPMI medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, except for Caco-2 cells, which were cultured in EMEM supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum. Cells were grown as attached monolayers and incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

Adenovirus vector construction and transfections

An expression cassette encoding the full-length 15-LOX-1 cDNA sequence under the control of the hTERT promoter and downstream polyadenylation signal was inserted into an Ad-5 shuttle plasmid, the Ad-5-hTERT-15-LOX-1 shuttle vector [12]. This shuttle plasmid was used to generate a recombinant adenoviral genome encoding 15-LOX-1 by homologous recombination in 293 human kidney fibroblasts with the plasmid pVK704 that encodes the chimeric adenoviral fiber 5/3 gene [47]. pVK704 was digested with PacI, purified, and then co-transfected with the Ad-5-hTERT-15-LOX-1 shuttle vector into 293 cells using Fugene 6 transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). The recombinant adenoviral vector that expresses 15-LOX-1 and the chimeric adenoviral fiber 5/3 (i.e., Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1; Figure 1a) was identified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis and plaque purified. All adenoviral vectors were expanded in 293 cells, purified, and titered by optical absorbance at A260 (one unit A260 = 1012 particles/ml) and by median tissue culture infective dose assay in 293 cells as described previously [48]. The titers of the viral preparations used in this study were between 1 × 1011 and 1 × 1012 viral particles/ml. The Ad-5-hTERT-15-LOX-1 shuttle plasmid was also used to generate an Ad-5 vector, Ad-5-15-LOX-1, using an AdEasy vector system (Qbiogene Inc., Carlsbad, CA) [32]. The control vector was generated as described for the Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 vector but with replacement of the 15-LOX-1 cDNA with luciferase (Luc) cDNA to generate Ad-5/3-Luc. Cells were transfected with the adenoviral vectors 24 hours after seeding in tissue culture dishes.

Quantitative real-time reverse-transcription PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using TRI reagent (Molecular Research Center Inc., Cincinnati, OH). The integrity of the total RNA was verified using the RNA 6000 Nano LabChip kit and an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). Five hundred nanograms of RNA from each sample was then reverse transcribed in a 20-μl reaction using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Real-time PCR and the measurement of relative RNA expression levels were performed as described previously [15].

Western blot analysis

Cell lysate proteins were extracted, separated, and blotted similarly to what has been described previously [15]. The blots were probed with a solution of rabbit polyclonal antibody to human 15-LOX-1 (1:2,000 dilution), XIAP (1:2,000), BcL-XL (1:2,000), and secondary antibody (1:10,000) and then analyzed using the enhanced chemiluminescence method (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ).

Enzyme immunoassay measurements

Organic phase extractions of cell lysates and cell culture media were prepared in a fashion similarly to that described previously [5]. 13-S-HODE was measured using commercially available kits (Assay Designs).

Cell survival and apoptosis measurements

Cell survival assessments were performed with sulforhodamine B, floating-to-total cell ratio, DNA fragmentation, and caspase-3 activity assays, as described previously [49].

Evaluation of the safety and antitumorigenic effects of Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 in vivo

Animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the institutional guidelines of The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center and with the approval of our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. We tested the safety of the Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 adenoviral vector in nude mice by comparing its effects in three groups of mice (n = 4/group) that were injected subcutaneously with PBS alone (control group) or with the Ad-5/3-Luc or Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 adenoviral vectors. Mice were given 2 × 1010 viral particles/injection in four separate injections over the course of 7 days. Blood samples were obtained for liver function studies (alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and alkaline phosphatase) 9, 22, and 37 days after the start of the injections. Mice were killed between 13 and 36 days after the last injection. Necropsies with histologic examinations of the brain, liver, kidneys, heart, spleen, pancreas, adrenal glands, and gastrointestinal tract were performed.

We tested the antitumorigenic effects of Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 using the experimental model of LoVo colon cancer cell xenografts in nude mice. LoVo xenografts were established in 6-week-old nu/nu nude mice (n = 35; Charles River Laboratories Inc., Wilmington, MA) by subcutaneous inoculation of 5 × 106 cells into their dorsal flanks. One xenograft was established in each flank of each animal (two xenografts/animal). After the tumors reached 3 mm in diameter, the mice were assigned randomly to one of three groups for treatment with PBS, Ad-5/3-Luc, or Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1. The adenoviral vectors (2 × 1010 viral particles in 50 μl of PBS/injection) or 50 μl of PBS were injected into the xenografts every 2 days for a total of four treatments. Xenografts were injected with the same treatment (PBS, Ad-5/3-Luc, or Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1) within the same animal. Tumor growth was evaluated by size measurements twice a week as described previously [12].

Statistical analyses

The data were log10 transformed to accommodate the assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity implicit to the statistical procedures used. We used one-way analysis of variance to compare various quantifiable outcome measures for one factor (e.g., caspase-3 activity) in experimental conditions (e.g., Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 and controls). Bonferroni adjustments were used for all multiple comparisons. Two-way analysis of variance was used to analyze data involving the simultaneous consideration of two factors. We first tested the interaction effect, and if the difference was significant, we subsequently performed specific comparisons to investigate which differences were driving this effect, using the Bonferroni correction to adjust for the multiple testing problem. The result of an individual comparison was considered significant only if the P value was less than 0.05/k, with k representing the number of comparisons performed. If the difference in interaction effect was not significant, we tested the individual main effects. When one of the factors was quantitative (e.g., concentration), we also used orthogonal polynomials to assess whether the relationship was linear, quadratic, or otherwise. When the interaction between a quantitative and group factor was significant, we used the orthogonal polynomial contrasts to test for differences between the groups. For example, in Figure 2a, evidence suggested a linear relationship in concentration, and we used orthogonal polynomial contrasts to assess the difference in concentration slopes between the Ad-5/3-Luc and Ad-5/3-15-LOX-1 groups. Then, if those results were significant, we determined which pairwise comparisons were significantly different, again adjusting for multiplicities using the Bonferroni correction. A growth-curve model was used to fit the xenograft growth data and assess whether 15-LOX-1 expression affected tumor growth using a log-linear mixed-effect model with treatments, time after injection, and their interaction as the fixed effects and the animal as a random effect.

All tests were two sided and conducted at the P ≤0.05 level. Data were analyzed using SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are in debt to Dr. L. Clifton Stephens, Section of Veterinary Pathology, The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, for performing necropsies and histologic examinations of nude mice. We also thank Karen Phillips from the Department of Scientific Publications at The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center for editing the manuscript. In addition, we acknowledge the assistance from Sijin Wen, Department of Biostatistics and Applied Mathematics, The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, in performing the statistical analyses. Dr. Imad Shureiqi was supported by the National Cancer Institute, NIH, Department of Health and Human Services R01 grant CA104278; by the American Cancer Society Research Scholar Award RSG-04-020-01-CNE; by the Caroline Wiess Law Endowment for Cancer Prevention; and by the National Colorectal Cancer Research Alliance. No author has any financial or other interests with regard to this manuscript that might be construed as a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hawk ET, Levin B. Colorectal cancer prevention. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:378–391. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gibbs JB. Mechanism-based target identification and drug discovery in cancer research. Science. 2000;287:1969–1973. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brash AR, Boeglin WE, Chang MS. Discovery of a second 15S-lipoxygenase in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:6148–6152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuhn H, Walther M, Kuban RJ. Mammalian arachidonate 15-lipoxygenases structure, function, and biological implications. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2002;68–69:263–290. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(02)00035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shureiqi I, Wojno KJ, Poore JA, Reddy RG, Moussalli MJ, Spindler SA, et al. Decreased 13-S-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid levels and 15-lipoxygenase-1 expression in human colon cancers. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:1985–1995. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.10.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nixon JB, Kim KS, Lamb PW, Bottone FG, Eling TE. 15-Lipoxygenase-1 has anti-tumorigenic effects in colorectal cancer. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2004;70:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heslin MJ, Hawkins A, Boedefeld W, Arnoletti JP, Frolov A, Soong R, et al. Tumor-associated down-regulation of 15-lipoxygenase-1 is reversed by celecoxib in colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2005;241:941–946. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000164177.95620.c1. discussion 946–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shureiqi I, Xu X, Chen D, Lotan R, Morris JS, Fischer SM, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs induce apoptosis in esophageal cancer cells by restoring 15-lipoxygenase-1 expression. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4879–4884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang WG, Watkins G, Douglas-Jones A, Mansel RE. Reduction of isoforms of 15-lipoxygenase (15-LOX)-1 and 15-LOX-2 in human breast cancer. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids. 2006;74:235–245. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hennig R, Kehl T, Noor S, Ding XZ, Rao SM, Bergmann F, et al. 15-Lipoxygenase-1 Production is Lost in Pancreatic Cancer and Overexpression of the Gene Inhibits Tumor Cell Growth. Neoplasia. 2007;9:917–926. doi: 10.1593/neo.07565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shureiqi I, Chen D, Lee JJ, Yang P, Newman RA, Brenner DE, et al. 15-LOX-1: a novel molecular target of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1136–1142. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.14.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shureiqi I, Jiang W, Zuo X, Wu Y, Stimmel JB, Leesnitzer LM, et al. The 15-lipoxygenase-1 product 13-S-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid down-regulates PPAR-delta to induce apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9968–9973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1631086100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsi LC, Xi X, Lotan R, Shureiqi I, Lippman SM. The histone deacetylase inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid induces apoptosis via induction of 15-lipoxygenase-1 in colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8778–8781. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deguchi A, Xing SW, Shureiqi I, Yang P, Newman RA, Lippman SM, et al. Activation of protein kinase G up-regulates expression of 15-lipoxygenase-1 in human colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8442–8447. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shureiqi I, Wu Y, Chen D, Yang XL, Guan B, Morris JS, et al. The Critical Role of 15-Lipoxygenase-1 in Colorectal Epithelial Cell Terminal Differentiation and Tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11486–11492. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grosch S, Maier TJ, Schiffmann S, Geisslinger G. Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)-independent anticarcinogenic effects of selective COX-2 inhibitors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:736–747. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolden JE, Peart MJ, Johnstone RW. Anticancer activities of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:769–784. doi: 10.1038/nrd2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnett BG, Crews CJ, Douglas JT. Targeted adenoviral vectors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1575:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(02)00249-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hunt KK, Vorburger SA. Tech.Sight. Gene therapy. Hurdles and hopes for cancer treatment. Science. 2002;297:415–416. doi: 10.1126/science.297.5580.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Everts M, Curiel DT. Transductional targeting of adenoviral cancer gene therapy. Curr Gene Ther. 2004;4:337–346. doi: 10.2174/1566523043346372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanerva A, Mikheeva GV, Krasnykh V, Coolidge CJ, Lam JT, Mahasreshti PJ, et al. Targeting Adenovirus to the Serotype 3 Receptor Increases Gene Transfer Efficiency to Ovarian Cancer Cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:275–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mathis JM, Stewart PL, Zhu ZB, Curiel DT. Advanced Generation Adenoviral Virotherapy Agents Embody Enhanced Potency Based upon CAR-Independent Tropism. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2651–2656. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imai K, Itoh F, Hinoda Y. Regulation of integrin function in the metastasis of colorectal cancer. Nippon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1998;99:415–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajecki M, Kanerva A, Stenman U-H, Tenhunen M, Kangasniemi L, Sarkioja M, et al. Treatment of prostate cancer with Ad5/3{Delta}24hCG allows non-invasive detection of the magnitude and persistence of virus replication in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:742–751. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim NW, Piatyszek MA, Prowse KR, Harley CB, West MD, Ho PL, et al. Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer. Science. 1994;266:2011–2015. doi: 10.1126/science.7605428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niiyama H, Mizumoto K, Sato N, Nagai E, Mibu R, Fukui T, et al. Quantitative analysis of hTERT mRNA expression in colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1895–1900. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takakura M, Kyo S, Kanaya T, Hirano H, Takeda J, Yutsudo M, et al. Cloning of human telomerase catalytic subunit (hTERT) gene promoter and identification of proximal core promoter sequences essential for transcriptional activation in immortalized and cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:551–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gunes C, Lichtsteiner S, Vasserot AP, Englert C. Expression of the hTERT gene is regulated at the level of transcriptional initiation and repressed by Mad1. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2116–2121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gu J, Kagawa S, Takakura M, Kyo S, Inoue M, Roth JA, et al. Tumor-specific transgene expression from the human telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter enables targeting of the therapeutic effects of the Bax gene to cancers. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5359–5364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gu J, Andreeff M, Roth JA, Fang B. hTERT promoter induces tumor-specific Bax gene expression and cell killing in syngenic mouse tumor model and prevents systemic toxicity. Gene Ther. 2002;9:30–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Majumdar AS, Hughes DE, Lichtsteiner SP, Wang Z, Lebkowski JS, Vasserot AP. The telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter drives efficacious tumor suicide gene therapy while preventing hepatotoxicity encountered with constitutive promoters. Gene Ther. 2001;8:568–578. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zuo X, Wu Y, Morris JS, Stimmel JB, Leesnitzer LM, Fischer SM, et al. Oxidative metabolism of linoleic acid modulates PPAR-beta/delta suppression of PPAR-gamma activity. Oncogene. 2006;25:1225–1241. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kamitani H, Geller M, Eling T. Expression of 15-lipoxygenase by human colorectal carcinoma Caco-2 cells during apoptosis and cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21569–21577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.21569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lowe SW, Cepero EE, van G. Intrinsic tumour suppression. Nature. 2004;432:307–315. doi: 10.1038/nature03098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boise LH, Gonzalez-Garcia M, Postema CE, Ding L, Lindsten T, Turka LA, et al. bcl-x, a bcl-2-related gene that functions as a dominant regulator of apoptotic cell death. Cell. 1993;74:597–608. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90508-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deveraux QL, Reed JC. IAP family proteins---suppressors of apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:239–252. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vrana JA, Decker RH, Johnson CR, Wang Z, Jarvis WD, Richon VM, et al. Induction of apoptosis in U937 human leukemia cells by suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) proceeds through pathways that are regulated by Bcl-2/Bcl-XL, c-Jun, and p21CIP1, but independent of p53. Oncogene. 1999;18:7016–7025. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosato RR, Maggio SC, Almenara JA, Payne SG, Atadja P, Spiegel S, et al. The Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor LAQ824 Induces Human Leukemia Cell Death through a Process Involving XIAP Down-Regulation, Oxidative Injury, and the Acid Sphingomyelinase-Dependent Generation of Ceramide. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:216–225. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.017145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim JS, Baek SJ, Bottone FG, Jr, Sali T, Eling TE. Overexpression of 15-lipoxygenase-1 induces growth arrest through phosphorylation of p53 in human colorectal cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2005;3:511–517. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu MK, Moos PJ, Cassidy P, Wade M, Fitzpatrick FA. Conditional expression of 15-lipoxygenase-1 inhibits the selenoenzyme thioredoxin reductase: modulation of selenoproteins by lipoxygenase enzymes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:28028–28035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313939200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodrigues NR, Rowan A, Smith ME, Kerr IB, Bodmer WF, Gannon JV, et al. p53 mutations in colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:7555–7559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.19.7555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Block A, Freund CT, Chen SH, Nguyen KP, Finegold M, Windler E, et al. Gene therapy of metastatic colon carcinoma: regression of multiple hepatic metastases by adenoviral expression of bacterial cytosine deaminase. Cancer Gene Ther. 2000;7:438–445. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nyati MK, Sreekumar A, Li S, Zhang M, Rynkiewicz SD, Chinnaiyan AM, et al. High and selective expression of yeast cytosine deaminase under a carcinoembryonic antigen promoter-enhancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2337–2342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brand K, Baker AH, Perez-Canto A, Possling A, Sacharjat M, Geheeb M, et al. Treatment of colorectal liver metastases by adenoviral transfer of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 into the liver tissue. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5723–5730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Midgley R, Kerr D. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1999;353:391–399. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07127-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jessup JM, McGinnis LS, Steele GD, Jr, Menck HR, Winchester DP. The National Cancer Data Base. Report on colon cancer. Cancer. 1996;78:918–926. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960815)78:4<918::AID-CNCR32>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dmitriev I, Krasnykh V, Miller CR, Wang M, Kashentseva E, Mikheeva G, et al. An Adenovirus Vector with Genetically Modified Fibers Demonstrates Expanded Tropism via Utilization of a Coxsackievirus and Adenovirus Receptor-Independent Cell Entry Mechanism. J Virol. 1998;72:9706–9713. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9706-9713.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fang B, Ji L, Bouvet M, Roth JA. Evaluation of GAL4/TATA in vivo. Induction of transgene expression by adenovirally mediated gene codelivery. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4972–4975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.4972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shureiqi I, Zuo X, Broaddus R, Wu Y, Guan B, Morris JS, et al. The transcription factor GATA-6 is overexpressed in vivo and contributes to silencing 15-LOX-1 in vitro in human colon cancer. Faseb J. 2007;21:743–753. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6830com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.