Abstract

To be effective as antiviral agent, AZT (3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine) must be converted to a triphosphate derivative by cellular kinases. The conversion is inefficient and, to understand why AZT diphosphate is a poor substrate of nucleoside diphosphate (NDP) kinase, we determined a 2.3-Å x-ray structure of a complex with the N119A point mutant of Dictyostelium NDP kinase. It shows that the analog binds at the same site and, except for the sugar ring pucker which is different, binds in the same way as the natural substrate thymidine diphosphate. However, the azido group that replaces the 3′OH of the deoxyribose in AZT displaces a lysine side chain involved in catalysis. Moreover, it is unable to make an internal hydrogen bond to the oxygen bridging the β- and γ-phosphate, which plays an important part in phosphate transfer.

Keywords: antiviral agents, phosphorylation, azido-thymidine, crystallography

AZT (3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine) and the dideoxy analogs of cytosine and inosine are major drugs against retroviral diseases. Upon infection by human immunodeficiency virus, these nucleoside analogs are incorporated by the reverse transcriptase copying the viral genome, and DNA synthesis terminates, because they lack the 3′OH needed for elongation of the polynucleotide chain. Because substrates for reverse transcriptase are deoxynucleoside triphosphates, the analogs must undergo phosphorylation before incorporation. This reaction is performed in several steps by cellular phosphokinases, and it is very slow beyond the first step. Thus, lymphocytes incubated with AZT accumulate inactive intermediates (1). With natural nucleotides, the conversion of the di- to the triphosphate is efficiently carried out by nucleoside diphosphate (NDP) kinase, an enzyme present in all organisms (2). Human cells have two isotypes, NDP kinases A and B, the products of the nm23-H1 and nm23-H2 genes (3). When the capacity of human NDP kinase B to phosphorylate derivatives of AZT and dideoxy-nucleosides was tested, it was found to be several orders of magnitude less than for natural substrates (4). This may make triphosphate production rate-limiting in viral inhibition by the drugs, and suggests that analogs that are better substrates of NDP kinase should also be better drugs.

To understand why NDP kinase is so unefficient in activating AZT, we determined a 2.3-Å x-ray structure of a complex with AZT diphosphate (AZT-DP) and compared it with a previously determined complex with thymidine diphosphate (dTDP) (5). The enzyme was a point mutant of the NDP kinase of the slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum, a 100-kDa hexamer that is highly similar to the human enzyme (57% sequence identity). It has a very similar three-dimensional structure, especially at the active site where all residues are conserved and make the same interactions with nucleotide substrates (6, 7). The structure of the complex shows that the analog binds at the same site and in the same way as natural substrates. It brings strong support to the conclusion that the 3′OH group of the sugar, missing in dideoxy compounds and replaced with a N3 azido group in AZT, is a major component of the mechanism of phosphate transfer catalysis by NDP kinase (4).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein Preparation and Crystallization.

Preparation of the N119A mutant of Dictyostelium NDP kinase has been described (8). The wild-type and N119A enzymes were expressed in Escherichia coli cells and purified as described (8) from the flow-through fraction of a DEAE-Sephacel (pH 8.4) column (Pharmacia) by adsorption on Blue Sepharose (Pharmacia) at pH 7.4 followed by elution in 0–2 M NaCl. Fractions were concentrated by ultrafiltration on Diaflo PM10 membranes (Amicon) and equilibrated in 50 mM Tris⋅HCl buffer (pH 7.4). The proteins were pure as judged by SDS/PAGE.

Commercially available nucleotides were obtained from Pharmacia, and [γ-32P]GTP (5,000 Ci/mmol; 1 Ci = 37 GBq) from Amersham. The diphosphate (AZT-DP) and triphosphate derivatives of AZT were synthesized as described (4). The purity of AZT-DP was checked by 31P NMR.

Crystals of the N119A–AZT-DP complex were grown in hanging drops over 32% PEG 550 as described for the wild-type NDP kinase–ADP–AlF3 complex (9), with 10 mM AZT-DP replacing ADP; 20 mM Mg2+ was present. They belong to space group P3121 (Table 1) with one-half of the 100-kDa hexamer in the asymmetric unit. Attempts to crystallize the wild-type protein–AZT-DP complex under similar conditions were unsuccessful.

Table 1.

Statistics on crystallographic analysis

| Parameter | Values |

|---|---|

| Diffraction data | |

| Space group | P3121 |

| Cell parameters a = b, c, Å | 71.59, 152.7 |

| Resolution, Å | 2.3 |

| Measured intensities | 134,673 |

| Unique reflections | 19,887 |

| Completeness, % | 86 |

| Rmerge, % | 6.3 |

| Refinement | |

| Rcryst(Rfree),† % | 21.6 (28.0) |

| Reflections | 16,845 |

| Protein atoms‡ | 3515 |

| Solvent atoms | 140 |

| Average B, Å2 | 23.5 |

| Geometry§ | |

| Bond length, Å | 0.013 |

| Bond angle, deg. | 1.9 |

| ω torsion angle, deg. | 1.5 |

Rmerge = Σhi |I(h)i − 〈I(h)〉|/Σhi I(h)i.

Rcryst = Σh ∥F0| − |Fc∥/Σh |F0| calculated on reflections with F > 2σ. Rfree was estimated by omitting 5% of the reflexions and running a final 100 steps of refinement.

Includes Mg2+ and nucleotide atoms.

Root-mean-square deviation from ideal values.

Enzyme Assay.

Assays of NDP kinase activity were performed as described (4) with either dTDP or AZT-DP as the phosphate acceptor and 1 mM [γ-32P]GTP as the donor. To prevent inhibition by the GDP reaction product, a regenerating system was included consisting of pyruvate kinase (0.3 unit) and phosphoenolpyruvate (1 mM). The test included 10 pg of enzyme when the substrate was dTDP, and 5 ng when it was AZT-DP. It was started by adding 3 μl enzyme in a 10 μl reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.4) and 5 mM MgCl2 and the substrates at 37°C; 3 μl aliquots were withdrawn at time intervals, heated for 2 min at 86°C, and then cooled on ice. An excess of cold nucleotides was added and the mixture was analyzed by thin layer chromatography using 0.4 M ammonium carbonate as solvent. After drying, the plates were exposed to a PhosphorImager screen (Molecular Dynamics) and the radioactivity in each spot was quantified as described (4).

Crystallographic Analysis.

X-ray diffraction data were collected at the W32 station of the Laboratoire pour l’Utilisation du Rayonnement Electromagnetique (LURE-DCI) synchrotron radiation center (Orsay, France) using a MAResearch imaging plate system. A single N119A–AZT-DP crystal was used. The wavelength was λ = 0.994 Å and the temperature was 4°C. Data reduction used the CCP4 package (10). The data had good statistics to 2.3-Å resolution (Table 1) and phases could be calculated using atomic coordinates of the isomorphous wild-type NDP kinase–ADP–AlF3 structure (9). Relative to this structure, the electron density map clearly showed the absence of the Asn-119 side chain and the replacement of ADP–AlF3 with AZT-DP. The density for the nucleotide analog was easily interpretable at two of three active sites in the asymmetric unit (subunits A and C). At the third site (subunit B), the phosphate positions were obvious, but the sugar and base density was weaker. An occupancy of 1 was therefore assumed for AZT-DP in subunit A and C, and 0.7 only at subunit B. The AZT moiety was taken from the x-ray structure (11) deposited in the Cambridge Structural Data Bank. Refinement was done with x-plor (12). The final model has an R factor of 21.6% and correct geometry (Table 1). It contains three NDP kinase subunits (residues 6–155), three bound AZT-DP–Mg2+ complexes, and 140 water molecules. As in other x-ray structures of Dictyostelium NDP kinase (13), N-terminal residues are disordered. The electron density is absent up to residue 5 and weak for residues 6–7. The three subunits in the asymmetric unit are identical to within experimental error over most of the polypeptide chain, the rms Cα deviation between pairs being 0.4 Å for residues 8–155. Main chain discrepancies up to 2 Å are nevertheless observed in the extended C-terminal segment at residues 145–147, which are poorly ordered and have above average temperature factors.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

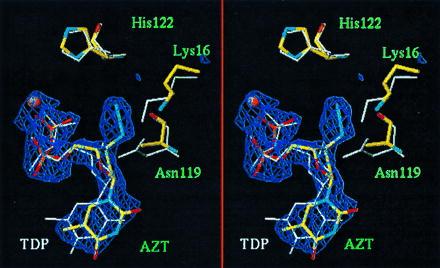

NDP kinase transfers the γ-phosphate of a nucleoside triphosphate donor to a diphosphate acceptor via a phospho-histidine intermediate (2, 14). It has a “ping-pong” type of mechanism and binds both donor and acceptor substrates at the same site located in a cleft on the surface of the hexamer. The cleft has a α-helix hairpin (helices αA–α2) on one side, a large loop called the Kpn loop on the other; the name refers to the killer-of-prune mutation of Drosophila (15), which is a point substitution in the equivalent loop of Drosophila NDP kinase. The bound nucleotide is oriented with the nucleobase pointing outside the protein, the phosphate groups pointing inside and toward the active site histidine, His-122 in Dictyostelium NDP kinase. Fig. 1 shows that AZT-DP binds at that site and in the same orientation as the natural substrate dTDP (5). The protein fold is essentially unchanged. The rms Cα deviation is 0.41–0.46 Å between subunits of the dTDP and AZT-DP complexes, comparable to the deviation between the three independent subunits of the latter. The Asn to Ala substitution at residue 119 has a small local effect on the main chain, which is displaced by 0.7 Å over two residues.

Figure 1.

Stereoview of the superimposed AZT-DP and TDP structures at the NDP kinase active site. The N119A–AZT-DP complex is colored by atom type; the wild-type–dTDP complex (5) has white bonds. The electron density for AZT-DP is contoured at 3 σ in a 2.3 Å Fo − Fc map. The thymine base points down toward outside the protein. The phosphates carry a Mg2+ ion (orange ball) and point toward the active site His-122 on top. Though the N119A mutation locally affects the main chain conformation, the protein structure is essentially the same in the two complexes and crowding by the 3′-azido group of AZT-DP is chiefly responsible for the observed movement of the Lys 16 side chain. Drawn with turbo (A. Roussel and C. Cambillau, Marseille, France, personal communication).

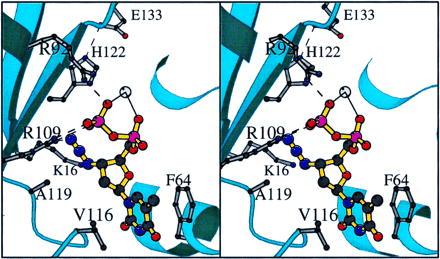

Interactions of AZT-DP with protein groups and Mg2+ are listed in Table 2. The thymine base lies in between the side chains of Phe-64 at the tip of the αA–α2 helix hairpin, and Val-116 of the Kpn loop (Fig. 2). Its polar groups make no direct interaction with the protein. Compared with dTDP, the base shifts in its plane by about 1 Å, and the Phe-64 side chain accompanies its movement. A very similar shift is observed with GDP or ADP (7, 17), the mobility of Phe-64 contributing to the lack of discrimination between purine and pyrimidine substrates which is a peculiar feature of NDP kinase. The phosphate moieties have identical positions in the AZT-DP and dTDP complexes. They bind arginine side chains and coordinate a Mg2+ ion in the same way, though the metal–oxygen bonds are long with AZT-DP suggesting that the metal site is partly occupied by solvent.

Table 2.

Nucleotide–protein contacts

| Nucleotide | Protein | Distance, Å* |

|---|---|---|

| Thymine ring | Phe-64 cycle | 3.6 (0.25) |

| Val-116 Cγ1 | 3.7 (0.25) | |

| α-phosphate O11 | His-59 Nɛ | 3.2 (0.15) |

| Mg2+ | 2.7 (0.25) | |

| β-phosphate O21† | Mg2+ | 2.6 (0.1) |

| Arg-92 Nη1 | 2.7 (0.2) | |

| O22 | Arg-109 Nη2 | 3.0 (0.15) |

| O7 | Arg-109 Nη1 | 3.1 (0.25) |

| AzidoN4 | Lys-16 Nζ | 3.6 (0.15) |

| N6 | Ala-119 Cβ | 3.7 (0.4) |

| Ile-121 O | 3.0 (0.4) | |

| His-122 Cβ | 3.5 (0.1) | |

| Arg-109 Nη1 | 3.0 (0.15) |

Average of three values observed in the crystallographic unit; the standard deviation is in parentheses.

In subunit B, the Mg2+ site is poorly occupied and appears to coordinate only the α-phosphate.

Figure 2.

NDP kinase interactions with AZT-DP. The N3 azido group in the center is in contact with the side chains of Lys-16, of Ala-119 replacing an asparagine in wild-type NDP kinase, and of His-122 on top. It may also hydrogen bond to Arg 109. The grey ball is a Mg2+ ion interacting with both phosphate groups. The stereopair was drawn with molscript (16).

The most noticeable difference between the natural substrate and the analog is the sugar pucker. The conformation of the nucleoside moiety of AZT-DP is C2′-endo with the base anti, essentially the same as in the crystal structure of AZT alone (11). In contrast, the deoxyribose is C3′-endo in bound dTDP (Table 3). As a result of the change in sugar pucker, the 3′-azido group moves away from the site normally occupied by the hydroxyl, where it would collide with protein atoms. Instead, it overlaps with the mobile ɛ-amino group of Lys-16. This is displaced by as much as 2.6 Å, whereas other active site residues stay essentially unperturbed. The azido group is also in van der Waals contact with the side chains of Ala-119 and His-122, and with the carbonyl group of Ile-121. In addition, it may receive a hydrogen bond from Arg-109 (Table 2).

Table 3.

Conformation of bound nucleotides

| Dihedral angle (deg.) | AZT | AZT-DP | dTDP |

|---|---|---|---|

| χ (glycosidic bond) | −125 | −128 (2) | −156 |

| γ (C5′-C4′ bond) | 52 | 63 (2) | 57 |

| P (sugar pucker) | 173 | 152 (6) | 31 |

Dihedral angles and the pseudo-rotation angle P are defined as in ref. 18. AZT is from the crystal structure of the free compound (11). AZT-DP are average values, with the standard deviation in parentheses, observed in the three independent subunits of the NDP kinase complex (this work). dTDP is from the complex with NDP kinase (5).

In NDP kinase, the 3′OH of the sugar in the bound substrate normally receives a hydrogen bond from the amide group of Asn-119 and donates one to the oxygen bridging the β- and γ-phosphates (O7 in Table 2) (5–7, 17). The azido group of AZT cannot make these interactions. Moreover, it is much bulkier than a hydroxyl, and the N119A mutant was designed to make room for it. The lack of a carboxamide group in alanine has only a local effect on the conformation of the polypeptide chain, but it does affect the catalytic activity, which in N119A NDP kinase is of the order of 10% of that of the Dictyostelium wild type (Table 4). With AZT-DP as the phosphate acceptor and GTP as the phosphate donor, the kinetic parameters of the Dictyostelium and human enzymes are similar (4). There is a ratio of 103 in kcat and 104 in kcat/KM in the relative efficiency toward dTDP and AZT-DP. In the mutant, the relative efficiency is 2 × 103 as measured by kcat/KM, the most significant parameter in an enzyme with a “ping-pong” mechanism, since its value for one substrate is independent of the other substrate concentration.

Table 4.

Phosphorylation of AZT-DP by wild-type and N119A mutant NDP kinase

| Enzyme acceptor substrate | WT

|

N119A

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dTDP | AZT-DP | dTDP | AZT-DP | |

| kcat, s−1 | 1,220 | 1.0 | 160 | 3.2 |

| KM, μM | 55 | 500 | 75 | 3,000 |

| kcat/KM, M−1⋅s−1 | 2.3 × 107 | 2 × 103 | 2 × 106 | 1 × 103 |

Enzyme assays were performed on wild-type (wt) and N119A Dictyostelium NDP kinases at 37°C as described in Materials and Methods. [γ-32P]GTP (1 mM) was the donor substrate, and either dTDP or AZT-DP was the acceptor substrate.

The present x-ray structure excludes the possibility that the low activity on AZT-DP reflects binding of the analog in a nonproductive way due to steric hindrance by the azido group. Alternative explanations are the induced movement of the Lys-16 side chain and the missing hydrogen bonds. The movement of Lys-16 apparently suffices to release crowding by the azido group. It has functional consequences, for the ɛ-amino group can no longer interact with the γ-phosphate of the donor nucleotide as it does in a normal substrate (7, 14). Substitution of Lys-16 with an alanine reduces activity to 0.2% (8). The role of the Asn-119 bond to the 3′OH is illustrated in Table 4 by kinetic data obtained on the N119A mutant with dTDP as a substrate: kcat/KM drops by a factor of 10 when the carboxamide group is deleted. The loss of the internal hydrogen bond of the 3′OH to the bridging phosphate oxygen in AZT-DP has much more effect and it must be a major reason for the low activity of NDP kinase on that substrate. Dideoxy-nucleotides that, like AZT-DP, are unable to make this bond are equally poor substrates of the human enzyme (4). The bridging oxygen is the leaving group when phosphorylating, and the attacking group when dephosphorylating the active site histidine. Therefore, to be efficiently activated by NDP kinase, a nucleoside analog must carry a hydrogen donor group comparable to the 3′OH and also occupy approximately the same location relative to the phosphates. The challenge is that it may not be a hydroxyl, nor any other group on which reverse transcriptase can add a phosphate to elongate the DNA chain. Our structural data should help in its design.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. LeBras (Laboratoire d’Enzymologie et de Biochimie Structurales, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Gif-sur-Yvette) for protein purification and crystallization, Dr. L. Tchernova (ICSN, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Gif-sur-Yvette) for searching the Cambridge Structural Data Bank, and the staff of Laboratoire pour l’Utilisation du Rayonnement Electromagnetique (Orsay, France) for access to the W32 station and help in data collection. This work was supported by Université Paris-Sud, Orsay, Agence Nationale de Recherche contre le SIDA, Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer, and the PRA B95-03 cooperative program between Université Paris-Sud and University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, China.

ABBREVIATIONS

- NDP

nucleoside diphosphate

- AZT

3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine

- AZT-DP

AZT diphosphate

- dTDP

thymidine diphosphate

Footnotes

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Chemistry Department, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, NY 11973 (reference 1LWX).

References

- 1.Balzarini J, Herdewijn P, De Clercq E. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:9062–9069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parks R E, Jr, Agarwal R P. Enzymes. 1973;8:307–334. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilles A M, Presecan E, Vonica A, Lascu I. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:8784–8789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourdais J, Biondi R, Sarfati S, Guerreiro C, Lascu I, Janin J, Véron M. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7887–7890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.7887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cherfils J, Moréra S, Lascu I, Véron M, Janin J. Biochemistry. 1994;33:9062–9069. doi: 10.1021/bi00197a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Webb P A, Perisic O, Mendola C E, Backer J M, Williams R L. J Mol Biol. 1995;251:574–587. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moréra S, Lacombe M L, Xu Y, LeBras G, Janin J. Structure. 1995;3:1307–13014. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00268-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tepper A, Dammann H, Bominaar A A, Véron M. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32175–32180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu Y, Moréra S, Janin J, Cherfils J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3579–3583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4. Acta Crystallogr A. 1994;50:157–163. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gurskaya G V, Tsapkina E N, Skaptsova N V, Kraevskii A A, Lindeman S V, Struchko Yu T. Dokl Akad Nauk SSSR. 1986;291:854. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brünger A T, Kuriyan J, Karplus M. Science. 1987;235:458–460. doi: 10.1126/science.235.4787.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moréra S, LeBras G, Lascu I, Lacombe M-L, Véron M, Janin J. J Mol Biol. 1994;243:873–890. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moréra S, Chiadmi M, LeBras G, Lascu I, Janin J. Biochemistry. 1995;34:11062–11070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Timmons L, Shearn A. Adv Genet. 1997;35:207–252. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kraulis P J. J Appl Crystallogr. 1991;24:949–950. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moréra S, Lascu I, Dumas C, LeBras G, Briozzo P, Véron M, Janin J. Biochemistry. 1994;33:459–67. doi: 10.1021/bi00168a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saenger W. Principles of Nucleic Acid Structure. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]