Abstract

While chemical synapses are very plastic and modifiable by defined activity patterns, gap junctions, which mediate electrical transmission, have been classically perceived as passive intercellular channels. Excitatory transmission between auditory afferents and the goldfish Mauthner cell is mediated by coexisting gap junctions and glutamatergic synapses. Although an increased intracellular Ca2+ concentration is expected to reduce gap junctional conductance, both components of the synaptic response were instead enhanced by postsynaptic increases in Ca2+ concentration, produced by patterned synaptic activity or intradendritic Ca2+ injections. The synaptically induced potentiations were blocked by intradendritic injection of KN-93, a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase (CaM-K) inhibitor, or CaM-KIINtide, a potent and specific peptide inhibitor of CaM-KII, whereas the responses were potentiated by injection of an activated form of CaM-KII. The striking similarities of the mechanisms reported here with those proposed for long-term potentiation of mammalian glutamatergic synapses suggest that gap junctions are also similarly regulated and indicate a primary role for CaM-KII in shaping and regulating interneuronal communication, regardless of its modality.

Keywords: long-term potentiation/gap junctions/synaptic plasticity/Mauthner cell

The degree of interneuronal communication via chemical synapses is a dynamic feature of the central nervous system and is mainly determined by the synapses’ own activity (1). In contrast, gap junction-mediated electrical synapses (2) are considered to be largely unmodifiable. Recent studies indicate, however, that these synapses also can undergo activity-dependent potentiation. As with chemical synapses, patterned synaptic activity has been shown to produce short- and long-term modifications of interneuronal coupling (3, 4).

Eighth nerve afferents (see Fig. 1a) terminate on the lateral dendrite of the M-cell as individual “large myelinated club endings” (5). Stimulation of the posterior branch of the eighth nerve evokes a mixed excitatory synaptic response in the dendrite (Fig. 1b) composed of a fast electrical potential followed by a chemical EPSP mediated by glutamate (6, 7). Because of the fast membrane time constant of the M-cell (about 400 μs; ref. 8), these two kinetically distinct components can be easily distinguished and reliably measured (Fig. 1b), providing a unique opportunity to dynamically explore modifications of junctional conductance under different physiological conditions.

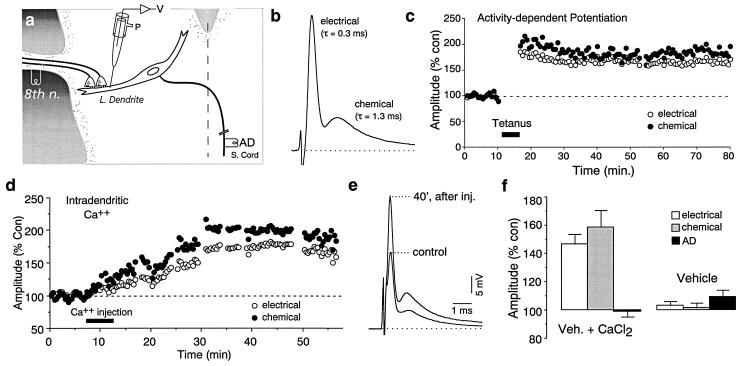

Figure 1.

Mixed synapses on the Mauthner cell (M-cell) exhibit activity-dependent potentiations. (a) Experimental arrangement (see Material and Methods). V, voltage; P, pressure; 8th n., eighth nerve; L. dendrite, lateral dendrite; AD, antidromic stimulation of the spinal cord (S. cord). (b) Eighth nerve stimulation evokes a fast electrotonic potential followed by a chemical glutamatergic excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP), with the indicated decay time constants. (c) Discontinuous tetanic stimulation of the nerve produces persistent homosynaptic potentiations of both components. Plots here and in subsequent figures illustrate the amplitudes of the electrotonic (○) and chemical ([circf) components versus time (each point represents the average of 20 traces) for one experiment. (d) Intradendritic injections of Ca2+ enhanced both components. (e) Superimposed traces represent the averages of 20 consecutive responses obtained in the control and 40 min after Ca2+ injection, at the maximum level of potentiation. (f) Bar plots represent the amplitudes (% of control) of the electrotonic potential, chemical EPSP, and antidromic spike (AD), all measured once the maximum potentiation had been reached. They averaged 146.4% (±7.2%) and 158.6% (±11.8%) of control for the electrical and chemical components, respectively (n = 5). Antidromic spike height, a measure of the cell’s input resistance, remained unchanged (98.8% ± 3.8%). Recordings made with the vehicle solution in the electrode did not affect the amplitudes, as measured at comparable time intervals, averaging 102.9% ± 2.8%, 101.6% ± 7%, and 109.4% ± 4.6%, for the electrical and chemical postsynaptic potentials and the AD spike, respectively (n = 5). Here and elsewhere, error bars represent 1 SEM.

As shown previously (3, 4), discontinuous high-frequency stimulation of the eighth nerve quickly induces homosynaptic potentiation (Fig. 1c) of both the electrical and glutamatergic components (3), which usually persist for the remainder of the experiment (up to 2 hr). However, the changes observed in both components of the synaptic response can be transient (4), lasting only for a period of 3–10 min, suggesting in the case of these gap junctions that junctional conductance is tightly regulated, perhaps involving post-translational modifications of gap junction channels. These short-term potentiations (STP; ref. 4) are likely to constitute the early phase of the long-lasting potentiations (LTP; ref.3), since in both cases the induction depends on the activation of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors and an increase in postsynaptic intracellular Ca2+. That is, they can be prevented by NMDA receptor antagonists and previous intradendritic injections of the Ca2+ chelator 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetate (BAPTA) (3, 4). The apparent role of Ca2+ contradicts the expectation that elevating its intracellular concentration should rather suppress gap junction conductance, given the direct inhibitory action of this cation on gap junction channels (9). On the other hand, stimulating paradigms known to promote an increase in presynaptic Ca2+ concentration (e.g., paired pulses, continuous high-frequency stimulation) were ineffective at inducing changes in junctional conductance (4).

We therefore investigated the role of Ca2+ and its molecular mechanism(s) in modulating both the electrical and chemical components of synaptic transmission in the goldfish M-cell. On the basis of this indirect evidence, we postulated that gap junctional conductance at these mixed synapses can be potentiated as a consequence of post- but not presynaptic elevations in Ca2+ concentration. The results presented here show that, in accord with this prediction, activity-dependent modulation of gap junctional conductance and glutamatergic transmission relies on a postsynaptic increase in the intracellular concentration of Ca2+, which in turn leads to activation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaM-KII), an essential step in the induction of the modifications.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Experimental Arrangement.

Responses to stimulation of the posterior eighth nerve or to antidromic stimulation of the spinal cord were recorded intracellularly in vivo from the M-cell’s lateral dendrite. The intracellular electrode was also used for iontophoretic or pressure injections. Responses were quantified after averaging sets of 20 or more consecutive traces. Student’s t test was used to assess statistical significance. Errors are presented as 1 SEM. To obtain activity-dependent potentiation, discontinuous tetanic stimulation of the nerve was used (trains of 4–6 pulses at 500 Hz applied every 2 s during 4 min; strength was sufficient to orthodromically activate the M-cell at least once per train; see refs. 3 and 4). Intraterminal recordings of large myelinated club endings (5–15 μm in diameter) were obtained at about 20 μm lateral to the initial penetration of the M-cell’s lateral dendrite.

Intracellular Injections.

For intradendritic injections the following compounds were added to the recording vehicle solutions and pressure injected into the M-cell’s lateral dendrite (see ref. 4): CaCl2 (2–6 mM in 0.5–2.5 M KCl/10 mM Hepes, pH 7.2); EGTA (5 mM in 2.5 M KCl/10 mM Hepes, pH 7.2); or KN-93, a CaM-K inhibitor (Seikagaku America, Rockville, MD; 200–300 μM in 0.5 M KCl/10 mM Hepes, pH 7.2). CaM-KIINtide, a potent and specific peptide inhibitor of CaM-KII: aliquots (10 μl) of 100 μM CaM-KIINtide were diluted to 50–70 μM in the electrode vehicle solution (0.5 M KCl/10 mM Hepes, pH 7.2) just before use and refrigerated. Electrode resistance was about 25 MΩ. The final intradendritic concentration of the peptide was lower than that in the electrode. α-CaM-KII: aliquots (5 μl) of 10 μM α-CaM-KII or heat-inactivated α-CaM-KII were diluted 2-fold in the electrode recording solution (0.5 M KCl/10 mM Hepes, pH 7.2) just before use and refrigerated. It was unnecessary to add phosphatase inhibitors to the recording solution (10).

For intraterminal injections, CaCl2 (2–4 mM) was added to the recording solution (2.5 M KCl/10 mM Hepes, pH 7.2) and Ca2+ was injected iontophoretically.

Immunohistochemistry and Immunoblot Analysis.

Affinity-purified samples of anti-peptide CaM-KII antibodies directed against sequences in the autoregulatory domain of the rat brain α subunit (G-301) or at the COOH-terminus of the association domain of the β/β′ subunits (RU-16) were used in all experiments (11). Fish were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde and brains were stored overnight. Vibratome sections (50 μm) were rinsed with PBS, incubated overnight with either G-301 (dilution 1:1000/5000; n = 7) or RU-16 (dilution 1:200/2000; n = 6), then rinsed in PBS and incubated for 2 hr with secondary antibodies conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), CY-3, or Texas red, rinsed again with PBS, and mounted on slides. Images obtained with a confocal microscope (Bio-Rad) were processed with nih image and canvas 3.1. Controls (n = 3) were obtained in the absence of primary antibodies.

To assess the specificity of both antibodies in goldfish brain, immunoblots were prepared as described (11), using ECL (enhanced chemiluminescence) reagents (Amersham) for detection. Rat cerebral cortex was rapidly dissected and homogenized in hot (95°C) 1% SDS. Whole goldfish brains were rapidly frozen and pooled prior to homogenization. Protein content was measured by using the BCA assay (Pierce) with BSA as the standard.

Kinase Assays.

To measure the specificity of CaM-KIINtide in goldfish brain we compared its effect on the activity of three kinases, CaM-KII, protein kinase A (PKA), and protein kinase C (PKC) (Fig. 3d). One goldfish brain was homogenized in 2 ml of a hypotonic solution (10 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5/1 mM EDTA/1 mM EGTA/1 mM DTT and protease inhibitor cocktail) and centrifuged at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected. Approximately 4 μg of protein was used per assay, which took place in a standard mixture of 50 mM Hepes at pH 7.5 (20 mM for PKC), 1 mM DTT, 10 mM MgCl2, and 0.4 mM [γ-32P]ATP. For CaM-KII, the activators were 0.8 mM Ca2+ and 2 μM calmodulin; for PKA, the activator was 1 mM cAMP with 1 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine; and for PKC it was 0.3 mM Ca2+, 0.14 mM phosphatidylserine, and 3.8 μM diacylglycerol. The substrates for CaM-KII, PKA, and PKC were 40 μM Syntide 2 (Peptide Express, Fort Collins, CO), 100 μM Kemptide (Peninsula Laboratories), and 100 μM epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) peptide, respectively.

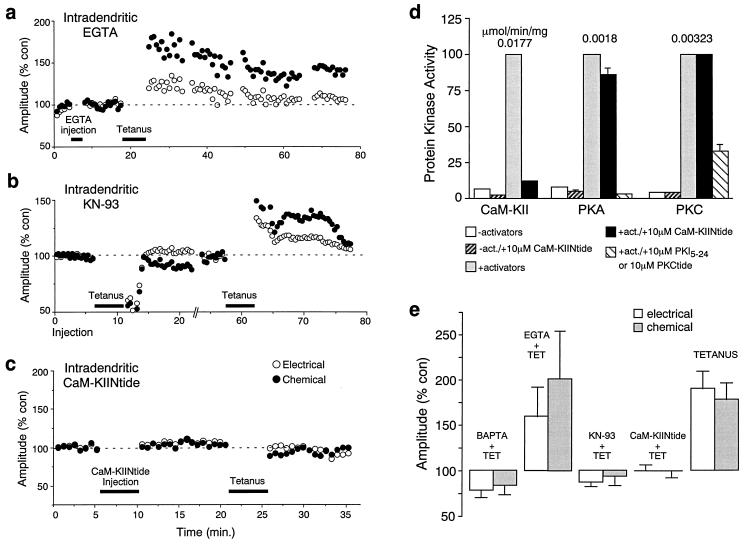

Figure 3.

Evidence that Ca2+ effects are mediated by CaM-KII. (a) Intradendritic EGTA injections did not prevent the induction of potentiations by tetanic eighth nerve stimulation. (b) Intradendritic injection of KN-93 blocked induction. In this experiment KN-93 was pressure injected for 3 min, ending at time 0, and PSP amplitudes postinjection were taken as controls. The antagonist itself had no significant effect. While tetanic stimulation 7–11 min after the injection failed (typically a transient depression followed unsuccessful tetani), a second tetanus 1 hr later successfully triggered potentiations of both components (each point represents the average of 15 traces). A new control was established at 50 min. (c) Intradendritic injections of CaM-KIINtide prevented the induction. (d) Specificity of CaM-KIINtide for CaM-KII in goldfish brain: Bar plots of protein kinase activity in the indicated conditions. CaM-KII was assayed for 1 min, PKA and PKC for 8 min each. Each column represents a mean and standard deviation of three data points. (e) To accurately estimate the effects of intradendritically injected compounds on the induction of these rapid activity-dependent potentiations, averages of the last 15–40 responses obtained before and after tetanic stimulation were compared. Bar plots represent the normalized posttetanus amplitude (% of control) of the electrotonic potential and chemical EPSP. BAPTA and EGTA at 5 mM have significantly different (P < 0.05) effects on induction (BAPTA + TET, EGTA + TET). In the presence of BAPTA, tetanic stimulation transiently depressed both PSPs, which averaged 78.1% (±9.8%, SEM) for the electrical and 83.8% (±7.4%, SEM) for the chemical, of their respective control amplitudes (n = 5; ref. 4). In the presence of EGTA the two components averaged 159.6% (±33.1%) and 202.6% (±53.2%), of their respective control amplitudes (n = 5). Intradendritic injections of KN-93 blocked activity-dependent potentiations (KN-93 + TET). Electrical and chemical responses averaged 86.8% (±4.4%) and 93.7% (±10.5%), of their respective control amplitudes (n = 9). CaM-KIINtide also prevented induction of the potentiations (CaM-KIINtide + TET; n = 12). In contrast, tetanic stimulation in controls (n = 30) produced potentiations that averaged 190.02% (±19.4%) and 178.8% (±18.2%).

RESULTS

Effects of Pre- and Postsynaptic Injections of Ca2+.

On the basis of indirect evidence, we postulated that gap junctional conductance at these mixed synapses can be potentiated as a consequence of post- but not presynaptic elevations in Ca2+ concentration. We directly tested this hypothesis by performing intradendritic and intraterminal recordings and injections close to the synapses themselves, a unique experimental advantage of this system. As predicted, intradendritic pressure injections of Ca2+ enhanced both components of the synaptic response. These enhancements grew slowly over a period of 10–15 min, attaining postsynaptic response magnitudes of approximately 150% of controls (Fig. 1 d–f). The M-cell antidromic spike height, a measure of the cell’s input resistance, remained unchanged (Fig. 1f). These Ca2+-induced potentiations occluded those evoked by eighth nerve tetani (n = 3, not shown). Response amplitudes for the electrical and chemical postsynaptic potentials (PSPs) and antidromic spike measured after at least 20 min of recording without Ca2+ in the electrode solution were not significantly different from controls (Fig. 1f). Thus, postsynaptic elevations of Ca2+ triggered an enhancement of gap junctional conductance.

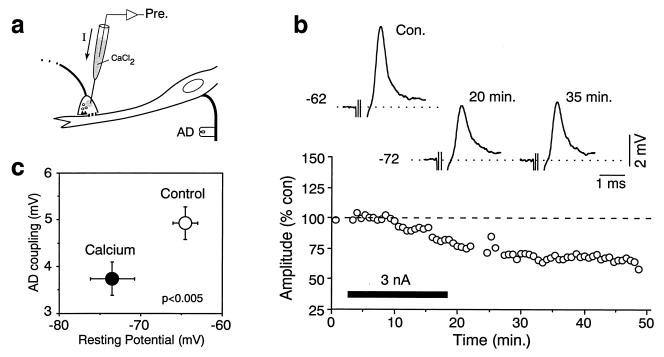

Intraterminal Ca2+ injections (Fig. 2a) did not enhance gap junctional conductance as measured by the electrotonic coupling potential in the terminal due to the passive dendritic depolarization produced by the antidromically evoked M-cell action potential (Fig. 2b Upper). Rather, they actually decreased the amplitude of the coupling potentials, an effect associated with a hyperpolarization of the terminals (Fig. 2b). On average (n = 11), the terminal resting potential was hyperpolarized, from 64.6 ± 1.5 mV to 73.4 ± 2.7 mV, and the coupling potential amplitude was reduced from 4.9 ± 0.4 mV to 3.7 ± 0.4 mV (Fig. 2c). Iontophoretic Ca2+ injections of shorter duration (not shown) resulted in reversible changes in both parameters, suggesting that these effects may be due to the activation of a Ca2+-dependent potassium conductance present at many synaptic terminals (12). Moreover, the decrease in the amplitude of the electrotonic potential can also be attributed to its previously shown voltage dependence in the terminal (13). Consistent with this finding, intraaxonal Ca2+ injections (afferent recording site in the eighth nerve root), performed while simultaneously recording the lateral dendrite, did not modify the amplitude of the orthodromically evoked unitary coupling potential, which averaged 94.1% ± 3.6% of control (n = 5). Therefore, the Ca2+-dependent process that triggers the modifications in junctional conductance is most likely restricted to the postsynaptic hemichannels.

Figure 2.

Presynaptic injections of Ca2+ do not increase junctional conductance. (a) Intraterminal recordings were obtained from large myelinated club endings, and Ca2+ was injected iontophoretically. (b) After Ca2+ injection the terminal was hyperpolarized from −62 to −72 mV in this case, and the antidromic coupling potential was decreased to approximately 70% of control (Upper). (Lower) Plot of the amplitude of the antidromic coupling potential versus time (each point represents the average of 10 traces) for the same experiment. (c) Diagram summarizing the values of the resting potential and coupling potential amplitudes (AD coupling) obtained for 11 terminals in control (○) and after at least 10 min of continuous Ca2+ injection (•). The changes were statistically significant.

Synaptically Induced Potentiations: Evidence for the Involvement of CaM-KII.

To determine whether induction of the enhancements depends on a localized rather than generalized intradendritic increase of Ca2+, we compared (14) the blocking efficacy of a slower Ca2+ buffer, EGTA, with that previously shown for a faster one, BAPTA (4). EGTA (5 mM) injected intradendritically prior to tetanic stimulation was a significantly less effective blocker of the potentiations than was 5 mM BAPTA. In the presence of BAPTA, tetanic stimulation transiently depressed both components of the synaptic response, whereas a clear potentiation was observed with EGTA (Fig. 3a). To accurately measure the effect of these buffers or other compounds (see above) on the induction of these rapid activity-dependent potentiations, we compared the averages of the last 15–40 traces obtained before and after tetanic stimulation. The dramatic difference between the effects of EGTA and BAPTA (Fig. 3e) suggests that a localized increase in Ca2+ is indeed responsible for the induction process.

Because this localized increase seems to be synaptically mediated through activation of NMDA receptor channels, the Ca2+ sensor responsible for the induction should be localized in the postsynaptic cell close to these channels. A likely candidate was multifunctional CaM-KII, whose α-subunit represents a major protein in the postsynaptic densities (PSDs; ref. 15) of vertebrate synapses and has a primary role in modulating neuronal synaptic plasticity (16–18). To test for involvement of CaM-KII, we first injected KN-93, a CaM-K inhibitor. As shown in Fig. 3b, KN-93 injection blocked both components of the synaptic response immediately after a tetanus, and this effect was reversible with time, presumably because of washout of the drug (Fig. 3 b and e).

The recent cloning of a CaM-KII inhibitor protein (CaM-KIIN) and a related 28-residue peptide that contains the inhibitory potency and specificity (CaM-KIINtide; see ref. 19) provided an alternative means to examine the effect of selective inhibition of CaM-KII on the induction of the activity-dependent potentiations. Although postsynaptic injection of other CaM-KII inhibitory peptides has been shown to block induction of long-lasting potentiation in region CA1 of mammalian hippocampus, those peptides have limited CaM-KII specificity and also inhibit several other kinases, thereby complicating interpretation of their effects (20–23). In contrast, CaM-KIINtide was shown to be a potent and highly specific inhibitor of CaM-KII activity from several species (19). The effect of CaM-KIINtide on CaM-KII, PKA, and PKC activities in soluble extracts from goldfish brain homogenates was tested (Fig. 4d). CaM-KIINtide inhibits goldfish CaM-KII with an IC50 of 300–400 nM, and it showed no significant inhibition of PKA or PKC at concentrations up to 10 μM. In confirmation of our hypothesis, intradendritic injections of this peptide prevented the activity-dependent potentiations (Fig. 3c). For 12 experiments in which the effect of this peptide was tested, the electrical and chemical components of the synaptic response averaged 100.3% ± 6.3% and 98.8% ± 7.6% of their control amplitudes prior to the tetanus, respectively (Fig. 3e). In addition, the effect of this peptide seems to be specific, since it has been shown that although intradendritic injections of the PKA inhibitory peptide PKI5–24 (see Fig. 3d) blocked the dopamine-mediated potentiations (24), they did not block induction of the activity-dependent enhancements [in a preliminary series, n = 5, PKI5–24 successfully prevented dopamine-evoked potentiations but was unable to block induction of activity-dependent potentiations (S. Kumar and D. S. Faber, personal communication)].

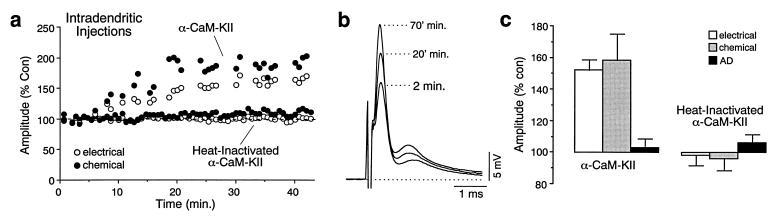

Figure 4.

Intradendritic injections of a constitutively active form of α-CaM-KII enhanced both components of the synaptic response. (a) Time course of two experiments in which recordings were obtained with electrodes containing either the constitutively active or a heat-inactivated form of α-CaM-KII. (b) Superimposed average traces (>20) obtained at different intervals after penetrating the dendrite with an electrode containing α-CaM-KII. Typically, leakage of α-CaM-KII alone caused continuously increasing potentiations. (c) Bar plots represent the normalized amplitudes of the synaptic components and antidromic (AD) spike measured at the end of the recording sessions in experiments with α-CaM-KII (30–80 min; electrical and chemical PSPs averaged 152.1% ± 6.5% and 158.3% ± 16.7% of their respective control amplitudes, respectively, n = 7) and heat-inactivated α-CaM-KII (40–80 min; corresponding synaptic responses averaged 98.3% ± 6.6% and 96% ± 7.4%, n = 7). M-cell antidromic spike height did not change significantly in either experimental series.

To further investigate the regulatory role of CaM-KII, we next determined whether intradendritic injections of a constitutively active form of CaM-KII could potentiate synaptic responses, as occurs in region CA1 of hippocampus (10). Indeed, CaM-KII injection resulted in slow increases in both components of the synaptic response to approximately 150% of control (Fig. 4 a–c). On the other hand, injecting a heat-inactivated form of this kinase did not increase the synaptic responses. M-cell antidromic spike did not change significantly in both experimental conditions (Fig. 4c). These enhancements did not saturate or plateau, which prevented us from examining whether the CaM-KII-induced potentiations occluded those evoked by tetanic stimulation.

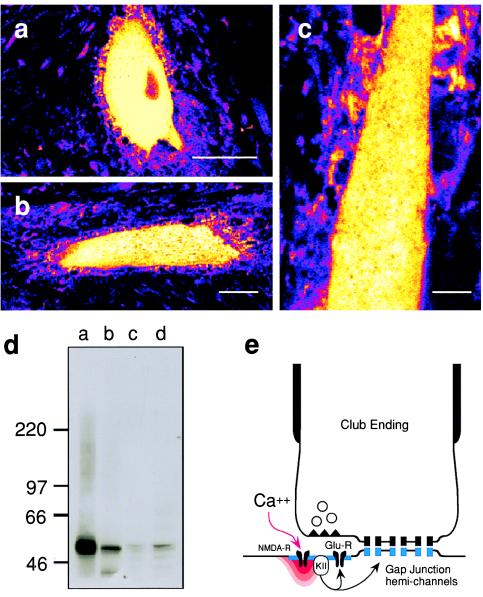

Immunohistochemistry using the G-301 antibody, which exhibits relative selectivity for the α-subunit of rat brain CaM-KII (Fig. 5 a–c), demonstrated that CaM-KII was present in the M-cells, particularly in their lateral dendrites (Fig. 5c), where these afferent synapses are localized. Immunoblot analysis of goldfish brain homogenate with G-301 revealed the presence of multiple immunoreactive bands of a size similar to the rat brain α-subunit (Fig. 5d). Studies using a second antibody, RU-16, directed against the C terminus of the β-subunit of rat CaM-KII, showed comparable results (data not shown).

Figure 5.

CaM-KII immunoreactivity is present in goldfish M-cells. (a–c) Immunohistochemical evidence for the presence of CaM-KII in the M-cell. Confocal (pseudocolor; white corresponds to maximum brightness) images obtained with the antibody G-301 (1:1000; Texas red). (a) Soma. (Bar: 50 μm.) (b) Lateral dendrite. (Bar: 30 μm.) (c) Higher magnification view of another stained lateral dendrite. (Bar: 15 μm.) Note the punctate staining surrounding the M-cell soma and lateral dendrite, most likely corresponding to the presynaptic localization of this enzyme. (d) Immunoblot using G-301 (1:200 dilution) and the following: lane a, 2 μg of rat cerebral cortex homogenate; lane b, 2.5 ng of CaM-KII purified from rat forebrain (11); lanes c and d, 30 μg and 90 μg, respectively, of goldfish brain homogenate. Molecular weight markers (× 10−3) are shown on the left. (e) Schematic representation of the proposed potentiating pathway. KII, CaM-KII; R, receptor.

DISCUSSION

Our data show that a postsynaptic elevation of Ca2+ concentration is an essential step for the induction of activity-dependent potentiation of the eighth nerve mixed synaptic responses. Although there could be other sources, this increase in Ca2+ is likely to be synaptically mediated, is probably localized to the postsynaptic densities (possibly forming a NMDA receptor microdomain), and leads to the activation of CaM-KII, which seems to be essential for the induction process (Fig. 5e). Because the changes are relatively rapid, and potentially transient, CaM-KII is also likely to be involved in at least the early phase of the expression of the potentiations. Likely targets of CaM-KII (Fig. 5e) are non-NMDA glutamate receptors (25, 26) and gap junction proteins (27). Although the mechanism of action of CaM-KII on gap junction channels is presently unknown, it is likely to involve changes in single channel conductance and/or open probability, as is the case for other kinases (28).

Multifunctional CaM-KII has a well established role in modulating chemical synaptic plasticity (16–18). The present results show that its modulatory role is not restricted to a specific modality of synaptic transmission, and they suggest a primary role for CaM-KII in shaping and regulating interneuronal communication in general. In the case of the M-cell system, the increased synaptic gain of these eighth nerve synapses will sensitize a vital escape response, lowering its threshold to auditory stimuli.

Finally, in contrast to the generally accepted tenet, elevations of intracellular Ca2+ concentration can lead to an increase in gap-junctional conductance. This effect is synaptically mediated and asymmetric—i.e., restricted to only one side of the gap junction plaque. This finding suggests that the hemichannels in the membrane of the postsynaptic M-cell are likely to be different in connexin composition from those in the presynaptic side (heterologous gap junctions; refs. 29 and 30) or that there may be different regulatory mechanisms in operation on the two sides of the connection, namely the M-cell dendrite and the afferent terminals. From the functional point of view, this asymmetric regulatory phenomenon implies that each individual neuron may be capable of exerting autonomous control of the degree of intercellular communication with its neighbors. This strategy could be essential for the rapid and tight regulatory control of these gap junctions in the M-cell system.

The gap junction regulatory mechanism described here may constitute a widespread property of electrical synapses that could apply to these junctions in other tissues. As an example, a synaptically mediated unilateral control mechanism may be relevant during neural development, where both gap-junctional coupling and activity-dependent synaptic plasticity are believed to play essential roles in establishing connections and creating functional compartments (31, 32).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DC03186 (to A.P.), NS15335 (to D.S.F), and NS27037 (to T.R.S.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- M-cell

Mauthner cell

- PSP

postsynaptic potential

- EPSP

excitatory PSP

- NMDA

N-methyl-d-aspartate

- BAPTA

1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetate

- CaM-KII

Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II

- PKA and PKC

protein kinases A and C

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the Proceedings Office.

References

- 1. Malenka R C, Nicoll R A. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:521–527. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90197-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett M V L. In: Cellular Biology of Neurons, Handbook of Physiology. Kandel E R, editor. 1, Sect. I. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1977. pp. 357–416. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang X D, Korn H, Faber D S. Nature (London) 1990;348:542–545. doi: 10.1038/348542a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pereda A, Faber D S. J Neurosci. 1996;16:983–992. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-00983.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartelmez G W. J Comp Neurol. 1915;25:87–128. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin J W, Faber D S. J Neurosci. 1988;8:1302–1312. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-04-01302.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolszon L, Pereda A, Faber D S. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:2693–2706. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.5.2693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukami Y, Furukawa T, Asada Y. J Gen Physiol. 1964;48:581–600. doi: 10.1085/jgp.48.4.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baux G, Simmoneau M, Tauc L, Segundo J P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:4577–4581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.9.4577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lledo P M, Hjelmstad G O, Mukherji S, Soderling T R, Malenka R C, Nicoll R A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11175–11179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamagata Y, Czernik A J, Greengard P. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:15391–15397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robitaille R, Charlton M P. J Neurosci. 1992;12:297–305. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-01-00297.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pereda A, Bell T, Faber D S. J Neurosci. 1995;15:5943–5955. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-09-05943.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adler E M, Augustine G J, Duffy S N, Charlton M. J Neurosci. 1991;11:1496–1507. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-06-01496.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kennedy M B, Bennett M K, Erondu N E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:7357–7361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.23.7357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barria A, Muller D, Derkach V, Griffith L C, Soderling T R. Science. 1997;276:2042–2045. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pettit D L, Perlman S, Malinow R. Science. 1994;266:1881–1885. doi: 10.1126/science.7997883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lisman J. Trends Neurosci. 1993;17:406–412. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang B H, Mukherji S, Soderling T R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10890–10895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malenka R C, Kauer J A, Perkel D J, Mauk M D, Kelly P T, Nicoll R A, Waxham M N. Nature (London) 1989;340:554–557. doi: 10.1038/340554a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malinow R, Schulman H, Tsien R W. Science. 1989;245:862–866. doi: 10.1126/science.2549638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith M K, Colbran R J, Soderling T R. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:1837–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hvalby O, Hemmings H C, Jr, Paulsen O, Czernik A J, Nairn A C, Godfraind J M, Jensen V, Raastad M, Storm J F, Andersen P, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4761–4765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pereda A, Triller A, Korn H, Faber D S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:12088–12092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mammen A L, Kameyama K, Roche K W, Huganir R L. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32528–32533. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barria A, Derkach V, Soderling T R. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32727–32730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.32727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saez J C, Nairn A C, Czernik A, Spray D C, Hertzberg E L, Greengard P, Bennett M V L. Eur J Biochem. 1990;192:263–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saéz J C, Berthoud V M, Moreno A P, Spray D C. In: Advances in Second Messenger and Phosphoprotein Research. Shirish Shenolikar S, Nairn A C, editors. Vol. 27. New York: Raven; 1993. pp. 163–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.White T W, Bruzzone R. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1996;28:339–350. doi: 10.1007/BF02110110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bruzzone R, White T W, Paul D L. Eur J Biochem. 1996;238:1–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0001q.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peinado A, Yuste R, Katz L. Neuron. 1993;10:103–114. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90246-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goodman, C. S. & Shatz, C. J. (1993) Cell 72/Neuron 10 (Suppl.), 427–437.