Abstract

ETS transcription factors play important roles in hematopoiesis, angiogenesis, and organogenesis during murine development. The ETS genes also have a role in neoplasia, for example in Ewing’s sarcomas and retrovirally induced cancers. The ETS genes encode transcription factors that bind to specific DNA sequences and activate transcription of various cellular and viral genes. To isolate novel ETS target genes, we used two approaches. In the first approach, we isolated genes by the RNA differential display technique. Previously, we have shown that the overexpression of ETS1 and ETS2 genes effects transformation of NIH 3T3 cells and specific transformants produce high levels of the ETS proteins. To isolate ETS1 and ETS2 responsive genes in these transformed cells, we prepared RNA from ETS1, ETS2 transformants, and normal NIH 3T3 cell lines and converted it into cDNA. This cDNA was amplified by PCR and displayed on sequencing gels. The differentially displayed bands were subcloned into plasmid vectors. By Northern blot analysis, several clones showed differential patterns of mRNA expression in the NIH 3T3-, ETS1-, and ETS2-expressing cell lines. Sixteen clones were analyzed by DNA sequence analysis, and 13 of them appeared to be unique because their DNA sequences did not match with any of the known genes present in the gene bank. Three known genes were found to be identical to the CArG box binding factor, phospholipase A2-activating protein, and early growth response 1 (Egr1) genes. In the second approach, to isolate ETS target promoters directly, we performed ETS1 binding with MboI-cleaved genomic DNA in the presence of a specific mAb followed by whole genome PCR. The immune complex-bound ETS binding sites containing DNA fragments were amplified and subcloned into pBluescript and subjected to DNA sequence and computer analysis. We found that, of a large number of clones isolated, 43 represented unique sequences not previously identified. Three clones turned out to contain regulatory sequences derived from human serglycin, preproapolipoprotein C II, and Egr1 genes. The ETS binding sites derived from these three regulatory sequences showed specific binding with recombinant ETS proteins. Of interest, Egr1 was identified by both of these techniques, suggesting strongly that it is indeed an ETS target gene.

ETS genes have been cloned and characterized from a variety of Metazoan species, ranging from human to Drosophila, that retains a region of similarity with the v-ets oncogene (1, 2). ETS family gene products bind specific purine-rich DNA sequences and transcriptionally activate a number of genes that contain ETS binding site(s) (EBS; refs. 1, 3). The ETS DNA binding domain is comprised of 85 amino acids (4); the secondary structures of ETS1 and FLI1 were determined recently by NMR analyses and indicated the presence of three α-helices and a four-stranded β-sheet similar to structures of helix–turn–helix motifs found in several mammalian and bacterial transcription factors (5–7). The ETS proteins are an important family of transcription factors that play roles in a number of biological processes, such as organogenesis during murine development, hematopoiesis, B cell development, signal transduction, as well as maintenance of T cells in the resting state and the subsequent activation of these T cells (8–11).

The ETS family genes and their products also have been implicated in several malignant diseases and pathological genetic disorders. For instance, ETS1, ETS2, and ERG have been shown to act as protooncogenes in that they can transform NIH 3T3 cells in vitro, and the subsequent injection of these cells into nude mice results in tumor formation (12–14). Furthermore, the FLI1 and ERG genes have been shown to be translocated and expresses chimeric fusion transcripts in almost all Ewing’s sarcomas as well as in a large number of other primitive neuroectodermal tumors (15–17). Thus, these findings are strongly suggestive of a basic role for these genes in the genesis of these types of tumors. Recently, the overexpression of ETS2 in transgenic mice has been shown to cause skeletal abnormalities phenotypically reminiscent of those seen in Down syndrome, in which ETS2 genes are known to be present in triplicate (18).

In view of the importance of the ETS family of transcription factors to various biological and pathological processes, the identification of downstream cellular target genes of the ETS family of transcription factors is warranted. The methods for elucidation of ETS targets used typically up to now have been mainly serendipitous or characterized by the purine-rich GGAA/T core sequences identified in the promoters/enhancers of various cellular or viral regulatory regions (1, 2). Subsequently, synthetic oligonucleotides containing EBS were used in electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) and transactivation assays using different ETS expression constructs together with reporter genes containing the minimum promoter linked to the prospective target genes EBS (19). Although these approaches have had some success, they suffer from several disadvantages: (i) They are not comprehensive in that they rely on EMSAs or transfection–transactivation assays; (ii) they often do not discriminate between the preferred target genes that are transactivated by the different members of the ETS family; and (iii) thus they may not adequately define the biological and/or pathological roles of specific members of the ETS family of transcription factors. Therefore, for this study, we used two novel approaches using RNA differential display and whole genome PCR to identify putative cellular target genes downstream of the ETS1 gene product (20–22). Of 59 clones identified by these combined techniques, 53 of them turned out to be unique and not previously identified or characterized. Of the five known genes, Egr1 was identified by both methods. The CArG binding factor (CBF) and the phospholipase A2 activating protein (PLA2P) were cloned and characterized by differential display. The other ETS gene targets, human serglycin and preproapolipoprotein C II were cloned and identified by whole genome PCR. The CBF gene product was found to be expressed in both ETS1- and ETS2-expressing cell lines using Northern blot analysis. Similar analysis found PLA2P expressed only in the ETS2-transformed cell line and Egr1 expressed only in the ETS1-transformed cells. None of these gene products was detected in any of the control NIH 3T3 cell lines. We also confirmed that the promoter regions of human serglycin, preproapolipoprotein, and Egr1 contain consensus EBS and are able to bind to the ETS proteins. Collectively, these findings (i) demonstrate the effective deployment of RNA differential display and whole genome PCR as novel approaches for discovering downstream cellular ETS target genes, and (ii), in this report, identify the Egr1 as an ETS target gene by both techniques.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

RNA Differential Display.

The method used for differential display was essentially as described by Liang and Pardee (21). Total RNA was prepared from cells by RNazol method and converted to cDNA by oligo(dT) and reverse transcriptase. cDNAs were amplified using T12MN and 5′ arbitrary primers provided in the RNA map differential display kit (GenHunter, Boston). After PCR, the samples were displayed on a 6% acrylamide DNA sequencing gels. The differentially displayed bands were recovered and subcloned into pBluescript (Stratagene), and the DNA sequence was analyzed by fasta and blast computer programs. The isolated cDNA fragments were used as probes to determine the differential expression by Northern blot analysis (23).

Whole Genome PCR.

HTB-166 genomic DNA digested with MboI was ligated to double stranded 43/39 unphosphorylated linkers using T4 DNA ligase (24): GATCCGGCAACGAAGGTACCATGGCCGCATAGGCCACTAGTGCGCCGTTGCTTCCATGGTACCGGCGTATCCGGTGATCACG. The linker ligated genomic DNA was incubated with recombinant ETS1 protein followed by immunoprecipitation with specific mAb (25). The ETS1 protein-bound DNA was released and amplified by PCR using primer I:GCACTAGTGGCCTATGCGG in the first two rounds of PCR amplification (22). Primer II:GTACCTTCGTTGCCGGATC was used in the fourth PCR round to minimize nonspecific amplifications. PCR amplification products were labeled with 32P using polynucleotide kinase and separated on a 6% polyacrylamide gel. The DNA bands in the range of 500 bp were recovered and digested with MboI and subcloned at the BamHI site of pBS (23). Recombinant clones were analyzed by DNA sequence analysis. The DNA sequences were evaluated by fasta and blast computer programs.

EMSA.

Nuclear extracts of recombinant proteins prepared in a baculovirus system were incubated with 32P-labeled oligonucleotides (50,000 cpm) in the presence or absence of mAb. Samples were electrophoresed on a 4% polyacrylamide gel in 0.25 × TBE buffer (90 mM Tris/64.6 mM boric acid/2.5 mM EDTA, pH 8.3) for 1.5 h at 250 V. The gel was dried and autoradiographed overnight (26, 27).

Chloramphenical Acetyltransferase (CAT) Assays.

The cotransfection experiments were done using CAT reporter plasmids containing Egr1–EBS and ETS expression vectors (ETS1 or FLI1) or CAT reporter plasmids containing the entire Egr1 promoter and specific deletion variants. The cells were harvested after 48–72 h and the cell extracts were normalized for the protein concentrations and β-galactosidase activity and assayed for CAT activity by thin layer chromatography (28, 29). Quantitation was performed by scanning TLC plates on the AMBIS radioisotopic imaging system (28, 29). All transfection experiments were repeated three times.

Northern Blot Analysis.

Total RNA was fractionated on 1.2% agarose gels containing formaldehyde followed by transfer on to Nytran membrane (23). Blots were hybridized with Egr1, PLA2P, and CBF probes (30).

RESULTS

Identification of Egr1 as a Putative ETS1 Target Gene Using RNA Differential Display.

To identify genes that are downstream targets of the ETS1 transcription factor, we used RNA differential display using RNA from NIH 3T3 cell line that has been transfected with ETS1 cDNA and produces high levels of ETS1 protein (12). The RNA differential display pattern of this ETS1-expressing cell line was compared with the differential display pattern from both the nontransfected parental NIH 3T3 and an ETS2-expressing cell line generated by transfection of ETS2 cDNA (14). More than 80 bands were found to be differentially expressed using eight different primer sets (see Material and Methods and ref. 21). From a total of 82 differentially expressed cDNA bands, 16 were found to be differentially expressed in reproducible fashion. These 16 bands were subcloned and subsequently analyzed by DNA sequencing and Northern blot analysis.

DNA sequence and fasta analyses revealed that three of the 16 clones represented sequences that had significant identity to other genes in the database; the other 13 clones may represent novel sequences not previously identified. The three specific clones identified by us corresponded to: PLA2P, CBF, and the Egr1) (Table 1; and refs. 31–33).

Table 1.

ETS target genes identified by differential display and whole genome PCR

| Clone | Strategy | Insert size, bp | Sequence homology | ETS–DNA binding | RNA expression

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIH 3T3 | ETS1 | ETS2 | |||||

| AE112 | DD* | 240 | CBF | ND | − | ++ | ++ |

| AE134 | DD* | 206 | PLA2P (rat) | ND | − | − | ++ |

| AE117 | DD* | 258 | Egr1 | + | − | ++ | − |

| L510 | WG† | 500 | Serglycin | + | ND | ND | ND |

| L45 | WG† | 500 | EGR1 | + | − | + | − |

| L29 | WG† | 500 | Preproapolipoprotein C II | + | ND | ND | ND |

ND, not determined.

Differential display: From 82 cDNA bands, three known and 13 unknown clones were isolated.

Whole genome PCR: Of 43 clones, three are known and 40 are unknown.

Identification of Egr1 as a Downstream Target Gene of ETS1 Using Whole Genome PCR.

To isolate and identify ETS target genes by whole genome PCR, the MboI-digested genomic DNA was ligated to unphosphorylated linkers to facilitate PCR amplification of the selected genomic fragments (24). Protein–DNA binding was carried out using linker-ligated DNA and recombinant ETS1 protein in the presence of ETS1 mAb E44 (25, 34). Recovery of the immunocomplexed ETS1 protein-bound DNA fragments was achieved with protein A-Sepharose. PCR amplification of the antibody-selected, ETS1-bound DNA was accomplished using primer I. The immunoprecipitation and PCR amplification were repeated twice using primer I. The selected fragments were subjected to a final round of amplification using primer II (see Materials and Methods). The resultant PCR-amplified DNA fragments were subcloned into the pBluescript vector at the BamHI site. Forty-three clones were sequenced and subjected to computer analysis using the fasta DNA sequence comparison program. Forty clones were found to be unlike any in the database although some showed partial homology with various known DNA sequences. Three clones that were found to be homologous to genes in the database were derived from the regulatory regions of the human serglycin, the preproapolipoprotein C II, and the Egr1 genes (Table 1) (33–36). The preproapolipoprotein gene promoter contains an EBS located 10 bp upstream of the TATA box (Fig. 1). The human serglycin promoter also contains an EBS at a position −75 to −71 from the RNA transcription start site (Fig. 1). Of interest, the Egr1 promoter contains multiple EBSs, two of those flank a CArG box, and a third site is flanked by two CArG boxes (Fig. 1). DNA sequences derived from these regulatory regions show specific binding with recombinant ETS1 and FLI1 proteins (see below). Significantly, the Egr1 gene was identified as a potential downstream cellular target gene of the ETS1 transcription factor using these two different methods, RNA differential display, and whole genome PCR. Consequently, in the next series of experiments, we focused our attention on the regulation of Egr1 promoter by ETS transcription factors.

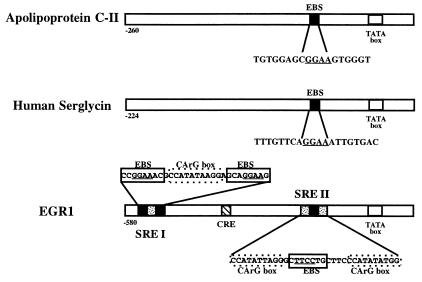

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of ETS target gene promoters. The ETS target gene promoters (Egr1, preproapolipoprotein C II, and serglycin) were identified by the whole genome PCR technique. Open rectangles indicate the promoter regions. TATA boxes and EBSs are indicated. The preproapolipoprotein C II and human serglycin promoters contain single EBSs whereas the Egr1 promoter contains multiple EBSs. Three of the EBS in Egr1 are part of serum response elements SREI and SREII as indicated.

The EBSs in the Egr1, Human Serglycin, and Preproapolipoprotein Promoters Are Able to Bind Recombinant ETS Proteins.

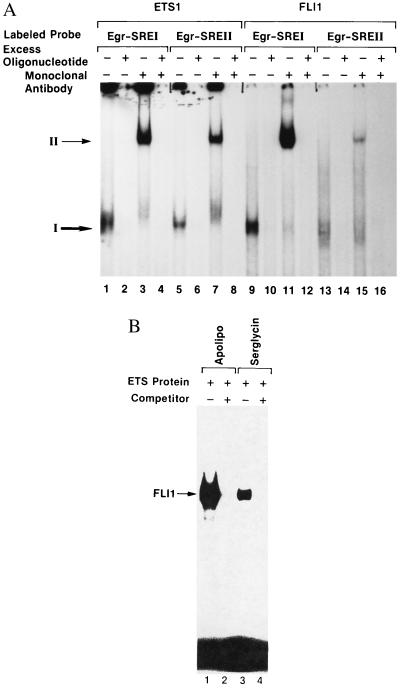

To validate the findings of our novel approaches to elucidate ETS targets, we tested the ability of recombinant ETS proteins to bind to the EBS located within the promoters isolated by whole genome PCR. EMSAs were carried out using synthetic oligonucleotides corresponding to the EBSs located in the Egr1, preproapolipoprotein, and human serglycin promoters (Fig. 1). The results demonstrate that recombinant ETS1 and FLI1 proteins bind to the ETS sites in Egr1, as well as serglycin and preproapolipoprotein promoters (Fig. 2). Although the ETS1 protein bound to both the Egr1–SREI and Egr1–SREII with equal efficiency, the FLI1 protein showed much higher affinity for the dual EBS-containing Egr1–SREI (Fig. 2a). The ETS1 and FLI1 DNA interactions are specific because the complexes can be supershifted with specific mAb (lanes 3, 7, 11, and 15) and can be competed out in the presence of excess unlabeled oligonucleotides (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16). Similarly, the FLI1 (Fig. 2b) and the ETS1 (data not shown) proteins also bound specifically to EBSs derived from preproapolipoprotein and serglycin promoters because the protein DNA interactions are effectively blocked with excess unlabeled oligonucleotides. These data illustrate that ETS proteins are able to bind to the EBSs present in Egr1, preproapolipoprotein, and serglycin promoter sequences.

Figure 2.

Interaction of ETS proteins with target promoters. (A) EMSA of ETS1 and FLI1 with Egr1 SREI and SREII. The ETS1 and FLI1 proteins were expressed in insect cells, and the cell extracts were prepared as described (19). Cell extracts (1 μg) contained ETS1 (lanes 1–8) and FLI1 (lanes 9–16) and SREI oligonucleotides (lanes 1–4 and 9–12) and SREII oligonucleotides (lanes 5–8 and 13–16) (19). The binding was performed in the presence of excess oligonucleotides (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16) and specific mAb (lanes 3, 7, 11, and 15). Arrows indicate protein–DNA complexes in the absence (I) or presence (II) of mAb. (B) EMSA of FLI1 with preproapolipoprotein C II serglycin promoters. 32P-labeled EBS containing oligonucleotides were incubated with FLI1 protein in the presence (lanes 2 and 4) or absence (lanes 1 and 3) of competitor. Arrow indicates the binding of FLI1 to preproapolipoprotein C II and serglycin promoter EBSs.

ETS Proteins Transactivate the Egr1 Promoter.

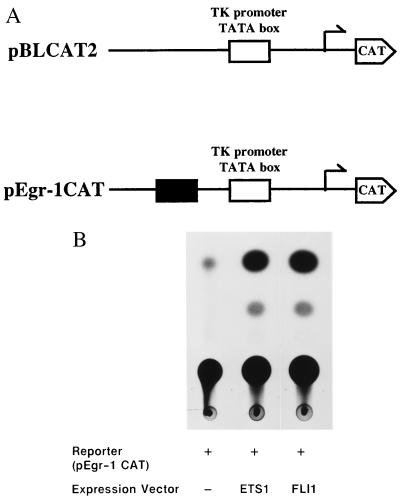

Having shown that ETS proteins bind the EBSs in the Egr1 promoter, we analyzed whether the ETS proteins are able to transactivate the Egr1 promoter. Cells were cotransfected with the ETS1 or FLI1 expression vector and the CAT construct containing Egr1 SREI (Fig. 3a) or with the ETS expression vectors and a control CAT construct lacking Egr1 EBSs (28, 29). We observed more than a 5-fold greater transactivation of the CAT gene from the Egr1 promoter construct compared with the control plasmid lacking EBS (Fig. 3b). Thus, the ETS proteins bound sequences within the Egr1 SREI and are able to transactivate transcription of the CAT reporter gene, further verifying our unique approach.

Figure 3.

Transient transactivation of CAT reporter via binding to Egr1 EBS by ETS1 and FLI1 proteins. (A) Map of the CAT reporter plasmids. The pBLCAT2 was used to construct reporter plasmid that contained the Egr1 SREI. (B) CAT assays were carried out with plasmids containing CAT reporter gene linked to Egr1 SREI and either ETS1 or FLI1 expression vectors. The CAT activity was examined by thin layer chromatography. The reaction products were quantified by analyzing the TLC plates on an AMBIS radioisotopic imaging system.

The Egr1 Promoter Contains Multiple EBSs, One of Which Is in a Region Essential for Promoter Functionality.

Mouse Egr1 promoter-linked CAT reporter gene constructs, and similar constructs with several deletions in the promoter region (Fig. 4a), were tested for expression in NIH 3T3 and COS cells (28). The largest promoter fragment (p903) and one that contained 667-bp sequences 5′ of the transcription initiation site (p667) were able to strongly effect CAT reporter expression (Fig. 4b). Both of these fragments contained two intact, serum response elements [note that the serum response elements contained EBS(s) together with a CArG box(es)]. Of interest, a promoter fragment (p666) that had one SRE disrupted by a deletion of the CArG box, together with the 5′ EBS, resulted in a dramatic reduction in promoter functionality (Fig. 4). Further deletion of the promoter resulted in a total loss of promoter functionality. These data demonstrate that SREI (a CArG box flanked by two EBSs, compare to. Fig. 1) is necessary for significant transactivational activity of the Egr1 promoter and that deletion of these site(s) results in a loss of most of the promoter activity. The SREII site, on the other hand, appears to be insufficient by itself to effect promoter activity function because the Egr1 promoter shows no effect using a construct that contained only an intact and presumably functional SREII site.

Figure 4.

Transactivation of Egr1 promoter linked to CAT gene. (A) Schematic representation of the CAT constructs containing serial deletions of promoter sequences (30). (B) Relative activity of each construct also has been shown. CAT assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods. The CAT activities were analyzed by thin layer chromatography as described in legend of Fig. 3. Three different concentrations of reporter vector were used, as indicated below each lane. CAT vectors p662 and p663 that lack the SREI are inactive in promoter activation assays.

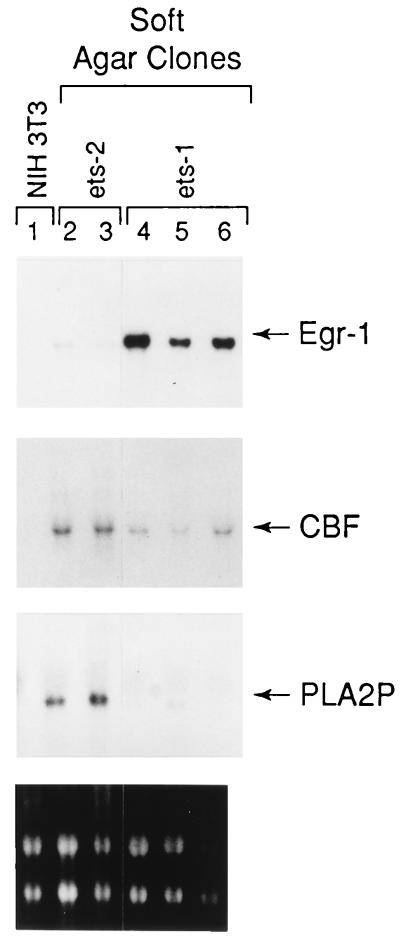

ETS1 and ETS2 Induce the Expression of ETS Target Genes Egr1, CBF, and PLA2P in NIH 3T3 Cells.

To study the regulation of candidate ETS target genes identified by differential display PCR and whole genome PCR techniques, we compared, by Northern blot analyses, the expression of Egr1, CBF, and PLA2P in ETS1-transfected NIH 3T3 cells to ones that had been transfected with ETS2 and parental controls (12, 14). Egr1 expression was induced in three independent clones of NIH 3T3 cells that had been transfected with ETS1 (Fig. 5). This effect was specific for ETS1 because Egr1 expression was either undetectable or weakly detectable in clones transfected with ETS2 (Fig. 5). Thus, these data demonstrate that ETS1 expression is sufficient to effect induction of Egr1 expression in NIH 3T3 cells. In contrast to Egr1, however, elevated expression of CBF occurs in both ETS1 and ETS2 transfectants (Fig. 5). On the other hand, the PLA2P gene product was found to be expressed only in the ETS2-expressing cell lines, that is, neither in the ETS1-expressing cells nor in nontransfected control NIH 3T3 cells, where endogenous ETS gene expression is low or absent. Thus, in the ETS1- and ETS2-expressing cells, these data consistently identify Egr1 promoter as a putative downstream cellular target gene for the ETS1 transcription factor, PLA2P as a target for the ETS2 transcription factor, and the CBF gene as a target for both of these ETS proteins.

Figure 5.

Northern blot analysis of ETS target gene expression. RNA was prepared from a control NIH 3T3 cell line and from two ETS2- and three ETS1-derived soft agar clone cell lines. Total RNA (10 μg) was loaded in each lane. For RNA integrity, the ethidium bromide staining of the gel before transfer onto nylon membrane is shown in the lowest panel. The blot was probed sequentially with Egr1, CBF, and PLA2P probes.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to reliably identify downstream cellular target genes that are either directly or indirectly regulated by the ETS transcription factors. Our initial approach applied the novel use of RNA differential display analyses of NIH 3T3 cells transfected with vectors expressing ETS1 or ETS2 transcription factors, respectively, and compared these to appropriate controls. The up-regulation of genes specifically in ETS1 transfectants was indicative of bona fide downstream cellular targets rather than genes whose expressions change as a consequence of transformation because the latter would also be up-regulated in both ETS1 and ETS2 transfectants. The differential display strategy allowed us to identify target genes that are either directly or indirectly regulated by ETS1 or ETS2 transcription factors. By this method, we isolated 16 previously unknown and three known genes (Egr1, CBF, and PLA2P). The second whole genome PCR approach used the binding of genomic DNA fragments with the recombinant ETS1 protein to isolate target promoters that are directly regulated by ETS transcription factors. By this method, we were able to clone 43 gene regulatory fragments. Three of those clones contained inserts that corresponded to the promoter regions of Egr1, preproapolipoprotein C II, and human serglycin genes. Important to note, Egr1 was identified by both the methods independently, indicating by its consistency that it is a bona fide ETS transcription factor target gene.

Human serglycin is a proteoglycan that is stored in secretory granules of many hematopoietic cells and is involved in its differentiation (37). The 5′ flanking regions of human and mouse serglycin genes have been characterized and show 96% identity in the 119-bp portion just upstream of the transcription start sites (38). Both of the promoters lack TATA boxes, but the GC-rich areas, however, contain cAMP response element binding/ATF (residues −70 to −65) and glucocorticoid receptor (residues −63 to −58) binding sites. By whole genome PCR approach, we identified an EBS in the 5′ flanking region (residues −75 to −80) of the human serglycin gene, which also is conserved in the mouse serglycin promoter region, suggesting that this site is important for transcriptional regulation. The expression of the human serglycin gene was shown to be up-regulated in a number of human leukemic cell lines, ones that coincidentally have been shown to express high levels of ETS1 and FLI1 (39, 40). In addition, we demonstrated that this site is functional in EMSAs with ETS1 and FLI1 proteins. Furthermore, similar to human serglycin, the ETS1 and FLI1 are also found to be expressed in hematopoietic cells, including activated T cells (41). Taken together, these observations suggest that the ETS1 and FLI1 transcription factors play an essential role in the regulation of human and mouse serglycin genes. The promoter of the preproapolipoprotein C II gene has an optimal EBS, containing the seven residues that are identical to the murine sarcoma virus–long terminal repeat; these sequences were originally used to establish the ETS1 as a sequence-specific DNA binding protein (42).

Analysis of the Egr1 promoter revealed two SREs (SREI and SREII), each containing CArG box(es) contiguous with EBS(s). The two SREs had different configurations; the distal one contained a CArG box flanked by two EBSs (SREI) whereas the proximal one contained a single EBS flanked by two CArG boxes (SREII). Deletion analysis demonstrated that the SREI is necessary for promoter function because removal of just this SRE resulted in a dramatic loss of promoter activity. It is important to note that this dramatic loss in promoter activity of p666 construct was achieved solely by the deletion of the most 5′ EBS and the CArG box of the SREI element. These findings provided further evidence for the Egr1 as a cellular target of an ETS family transcription factor. The finding that ETS1 binds to and transactivates transcription from the Egr1-SREI suggests that Egr1 is a cellular target of ETS1. Further support for this comes from the data showing that Egr1 expression is up-regulated only in ETS1-expressing, and not in ETS2-expressing, NIH 3T3 cells.

SREs regulate the expression of various immediate early genes, including c-fos, Egr1, and pip92 (32, 43, 44). EMSAs demonstrated the ability of ETS1 and FLI1 to bind the EBSs located within the Egr1 SREs. This finding is intriguing because data currently in the literature suggest that the ETS proteins (ELK1 and SAP1a) do not form binary complexes with c-fos SRE and require SRF to form ternary complexes (3, 43). In this study and recently, we have shown that ETS proteins such as ETS1, ETS2, FLI1, EWS-FLI1, ELK1, and SAP1a can form binary complexes with the Egr1 SREs and that ELK1, SAP1a, FLI, and EWS-FLI1 also can form ternary complexes with the Egr1 SREs (45). It is possible that all ETS proteins may be capable of binding to specific SREs; however, some of these binding interactions will be dependent and modulated by SRF, and others will be independent of interactions with SRF. However, the issue of which specific ETS family member binds to specific SRE depends, perhaps, on the context of specific sites (EBS or CArG) located within a given promoter. This is supported by our previous finding that spatial configurations of EBSs within the p53 promoter influence the specificity with which individual ETS family proteins bind these sequences (27). In addition, our data demonstrate that FLI1 can form ternary complex on the Egr1 SRE but not on the c-fos SRE (45). However, ELK1, SAP1a, and EWS-FLI1 can form ternary complexes on both the Egr1 and c-fos SREs. These findings suggest that the Egr1 promoter is regulated stringently and, depending on the cell types, it may be regulated by different ETS proteins in a SRF-dependent or -independent manner.

Similar to SRF, CBF binds to CArG boxes found in different promoters, acting as a transcriptional repressor on smooth muscle α-actin genes (32). Significantly, there is an EBS site adjacent to the CArG box in the regulatory region of smooth muscle α-actin gene. It would be interesting therefore to explore the possibility of protein–protein interaction between CBF and various ETS factors.

In this paper, we demonstrate that ETS1 is able to regulate expression of EGR1, which has been shown to bind to defined DNA sequences, thereby regulating protooncogenes, genes encoding mitogens, and mitogen receptors that are involved in cell growth and transformation (46). Up-regulation of EGR1 may therefore be an important step in transformation of NIH 3T3 cells transfected with ETS1. Taken together, our results provide the first evidence that ETS1- and ETS2-induced transformation involves the activation of specific transcription factors and defines the expression of these genes as possible molecular mechanisms in ETS-mediated cellular transformation.

Finally, the data in this study provide evidence for the utility of RNA differential display and/or whole genome PCR for the identification of genes that are downstream cellular targets of specific transcription factors. Because this is one of the major aims of transcription factor biology, it is incumbent that these multiple approaches be used for such studies that can then be validated by EMSA and transcription transactivational analysis. Collectively, these techniques should reveal additional and unique targets for the ETS family transcription factors. In a broader sense, these approaches can be extended to compare multiple samples derived from cells containing ETS transcriptional factor gene mutations and translocations, thus providing leads to ETS targets that are of clinical importance.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Thompson for technical assistance, Richard Ascione for reading of the manuscript, and V. P. Sukhatme for providing the Egr1 promoter constructs. Part of this work was funded by a Medical Research Council Canada Group Grant to A.S., American Cancer Society Grant CN-164 to T.S.P., and by the Medical Research Council of Australia and the Anti-Cancer Council of Victoria to I.K.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CBF

CArG box binding factor

- PLA2P

phospholipase A2 activating protein

- EBS

ETS binding sites

- EMSA

electrophoretic mobility shift assays

- CAT

chloramphenicol acetyltransferase

References

- 1.Seth A, Ascione R, Fisher R J, Mavrothalassitis G J, Bhat N K, Papas T S. Cell Growth Differ. 1992;3:327–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsylyk B, Hahn S L, Giovanne A. Eur J Biochem. 1993;211:7–18. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78757-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janknecht R, Nordheim A. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1155:346–356. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(93)90014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelsen B, Tian G, Erman B, Gregoire J, Maki R, Graves B, Sen R. Science. 1993;261:82–86. doi: 10.1126/science.8316859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liang H, Olejniczak E T, Mao X, Nettesheim D G, Yu L, Thompson C B, Fesik S W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11655–11659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donaldson L W, Petersen J M, Graves B J, McIntosh L P. Biochemistry. 1994;33:13509–13516. doi: 10.1021/bi00250a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Werner M H, Clore G M, Fisher C L, Fisher R J, Trinh L,, Shiloach J, Gronenborn AM. Cell. 1995;83:761–771. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kola I, Brookes S, Green A R, Garber R, Tymms M, Papas T S, Seth A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7588–7592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maroulakou I G, Papas T S, Green J E. Oncogene. 1994;9:1551–1565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muthusamy N, Barton K, Leiden J M. Nature (London) 1995;377:639–642. doi: 10.1038/377639a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhat N K, Thompson C B, Lindsten T, June C H, Fujiwara S, Koizumi S, Fisher R J, Papas T S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:3723–3727. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.10.3723. ,. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seth A, Papas T S. Oncogene. 1990;5:1761–1767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Topol L Z, Tatosyan A G, Ascione R, Thompson D M, Blair D G, Kola I, Seth A. Cancer Lett. 1992;67:71–78. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(92)90010-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seth A, Watson D K, Blair D G, Papas T S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7833–7837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.7833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delattre O, Zucman J, Plougastel B, Desmaze C, Melot T, Peter M, Kovar H, Joubert I, de Jong P, Rouleau G, Aurias A, Thomas G. Nature (London) 1992;359:162–165. doi: 10.1038/359162a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sorensen P H, Lessnick S L, Lopez-Terrada D, Liu X F, Triche T J, Denny D T. Nat Genet. 1994;6:146–141. doi: 10.1038/ng0294-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.May W A, Lessnick S L, Braun B S, Klemsz M, Lewis B C, Lunsford L B, Hromas R, Denny C T. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:1793–1798. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.12.7393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sumarsono S H, Wilwon T J, Tymms M J, Venter D J, Corrick C M, Kola R, Lahoud M H, Papas T S, Seth A, Kola I. Nature (London) 1996;379:534–538. doi: 10.1038/379534a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seth A, Robinson L, Panayiotakis A, Thompson D M, Hodge D R, Zhang X K, Watson D K, Ozato K, Papas T S. Oncogene. 1994;9:469–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang P, Averboukh L, Keyomarsi K, Sager R, Pardee A B. Science. 1992;257:967–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang P, Pardee A B. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6966–6968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Deiry W S, Kern S E, Pietenpol J A, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B. Nat Gen. 1992;1:45–49. doi: 10.1038/ng0492-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Handbook. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seth A. Gene Anal Tech. 1984;1:99–103. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koizumi S, Fisher R J, Fujiwara S, Jorcyk C, Bhat N, Seth A, Papas T S. Oncogene. 1990;5:675–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seth A, Hodge D R, Thompson D M, Robinson L, Panayiotakis A, Watson D K, Papas T S. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1993;9:1017–1023. doi: 10.1089/aid.1993.9.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Venanzoni M C, Robinson L R, Hodge D R, Kola I, Seth A. Oncogene. 1996;12:1199–1204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hodge D R, Thompson D M, Panayiotakis A, Seth A. In: Methods in Molecular Biology: Transcription and Translation Protocols. Tymms M J, editor. Clifton NJ: Humana; 1995. pp. 409–421. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hodge D R, Robinson L, Watson D, Lautenburger J, Zhang X K, Seth A. Oncogene. 1996;12:11–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sukhatme V P, Cao S M, Chang L C, Tsai-Morris C H, Stamenkovick D, Ferreira P C, Cohen D R, Edwards S A, Shows T B, Curran T, Le Beau M, Adamson E. Cell. 1988;53:37–43. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90485-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang H, Lemasters J, Herman B. Gene. 1995;161:237–241. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00253-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamada S, Miwa T. Gene. 1992;119:229–236. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90276-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Christy B, Lau L F, Nathans D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:7857–7861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.7857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seth A, Robinson L, Thompson D M, Watson D K, Papas T S. Oncogene. 1993;8:1783–1790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fojo S S, Law S W, Brewer H B., Jr FEBS Lett. 1987;213:221–226. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81495-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Humphries D E, Nicodemus C F, Schiller V, Stevens R L. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:13558–13563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toyama-Sorimachi N, Sorimachi H, Tobita Y, Kitamura F, Yagita H, Suzuki K, Miyasaka M. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7437–7444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nicodemus C F, Avraham S, Austen K F, Purdy S, Jablonski J, Stevens R L. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:5889–5896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maillet P, Alliel P M, Mitjavila M T, Perin J P, Jolles P, Bonnet F. Leukemia. 1992;6:1143–1147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Papas T S, Watson D K, Sacchi N, Fujiwara S, Seth A K, Fisher R J, Bhat N K, Mavrothalassitis G, Koizumi S, Jorcyk C L, Schweinfest C W, Kottaridis S D, Ascione R. Am J Med Genet. 1990;7:251–261. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320370751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhat N K, Thompson C B, Lindsten T, June C H, Fujiwara S, Koizumi S, Fisher R J, Papas T S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:3723–3727. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.10.3723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gunther C, Nye J, Bryner R, Greaves B. Genes Dev. 1990;4:667–679. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.4.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dalton S, Treisman R. Cell. 1992;68:597–612. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90194-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Latinkic B V, Lau L F. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:23163–23170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watson D K, Robinson L, Hodge D R, Kola I, Papas T S, Seth A. Oncogene. 1997;14:213–221. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lemaire P, Vesque C, Schmitt J, Stunnenberg H, Frank R, Charnay P. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:3456. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.7.3456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]