Abstract

During reverse transcription of retroviral RNA, synthesis of (−) strand DNA is primed by a cellular tRNA that anneals to an 18-nt primer binding site within the 5′ long terminal repeat. For (+) strand synthesis using a (−) strand DNA template linked to the tRNA primer, only the first 18 nt of tRNA are replicated to regenerate the primer binding site, creating the (+) strand strong stop DNA intermediate and providing a 3′ terminus capable of strand transfer and further elongation. On model HIV templates that approximate the (−) strand linked to natural modified or synthetic unmodified tRNA3Lys, we find that a (+) strand strong stop intermediate of the proper length is generated only on templates containing the natural, modified tRNA3Lys, suggesting that a posttranscriptional modification provides the termination signal. In the presence of a recipient template, synthesis after strand transfer occurs only from intermediates generated from templates containing modified tRNA3Lys. Reverse transcriptase from Moloney murine leukemia virus and avian myoblastosis virus shows the same requirement for a modified tRNA3Lys template. Because all retroviral tRNA primers contain the same 1-methyl-A58 modification, our results suggest that 1-methyl-A58 is generally required for termination of replication 18 nt into the tRNA sequence, generating the (+) strand intermediate, strand transfer, and subsequent synthesis of the entire (+) strand. The possibility that the host methyl transferase responsible for methylating A58 may provide a target for HIV chemotherapy is discussed.

Keywords: reverse transcription, strand transfer, HIV, tRNA

During reverse transcription, reverse transcriptase (RT) catalyzes the conversion of the single-stranded RNA genome to duplex DNA by first producing a (−) strand of DNA using the RNA genome as a template, followed by generation of the (+) strand DNA using the newly formed (−) strand as a template (Fig. 1) (1). Two intermediates in this process, (−) and (+) strand strong stop DNA intermediates which undergo strand transfer, have been found by using detergent-disrupted virions to perform reverse transcription in the presence of added deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Fig. 1 b and d) (1, 2). With model as well as natural substrates, many steps in the retroviral DNA replicative life cycle have been reconstituted. For example, the mechanism for generation of the (−) strand strong stop DNA intermediate and subsequent (−) strand transfer has been described (3).

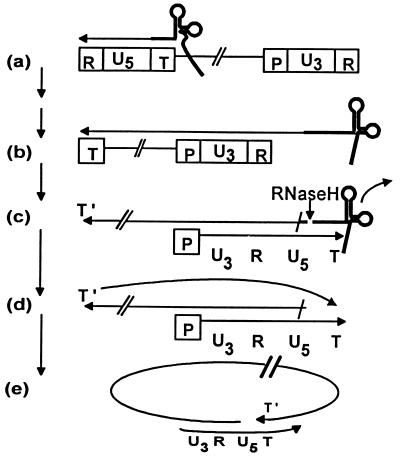

Figure 1.

Partial model for reverse transcription of retroviral RNA. T represents the tRNA primer binding site in the 5′ long terminal repeat, R is the terminally redundant sequence in both long terminal repeats, P is the polypurine tract that provides the primer for (+) strand synthesis, and U3 and U5 are unique sequence elements found in 3′ and 5′ long terminal repeats, respectively. A cellular tRNA primes (−) strand synthesis, resulting initially in the formation of the (−) strand strong stop DNA intermediate (a). The replicated RNA template is degraded by RNaseH, enabling (−) strand transfer (not shown) by annealing of complementary 5′ and 3′ R sequences, which leads to synthesis of a full-length (−) strand (b). Degradation of the replicated RNA template except for a preserved polypurine tract (P), and the ensuing (+) strand synthesis initiated from primer P, stops 18 nt into the tRNA primer (c), regenerating T and forming the (+) strand strong stop DNA intermediate. The tRNA is degraded by RNaseH (c), permitting annealing of the complementary sequences T and T′ (d) and creating a template (e) used for full-length (+) strand synthesis.

All replication-competent retroviruses contain an 18-nt primer binding site complementary to the 3′ end of a cellular tRNA that primes (−) strand synthesis (Fig. 1a) (1, 4–6). HIV primes its synthesis using tRNA3Lys (7); tRNATrp and tRNAPro provide primers for avian myoblastosis virus (AMV) (8, 9) and Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) (10), respectively. After synthesis of the (−) strand DNA, the tRNA primer remains covalently linked to the newly formed (−) strand and serves as a partial template for (+) strand synthesis. Plus-strand DNA synthesis is initiated from a polypurine tract within the 3′ long terminal repeat (11–13) that is resistant to the action of RNaseH of RT (14–19). Replication proceeds only 18 nt into the tRNA primer, where it stops to generate the (+) strand strong stop DNA intermediate (20). This replicated portion of the tRNA is complementary to the primer binding site that is regenerated without replicating the remaining sequence of the tRNA (2, 11, 20, 21). It has been suggested that the posttranscriptional modification, 1-methyl-A58 (m1A58), which exists 19 nt from the 3′ end of all tRNAs that prime retroviral DNA production, is the signal that terminates (+) strand synthesis to generate the (+) strand strong stop DNA intermediate (1). This hypothesis and the question of whether generation of the proper (+) strand strong stop intermediate is necessary for (+) strand transfer have never been experimentally tested (to our knowledge).

After its replication, but before (+) strand transfer, the tRNA sequence is cleaved by RNaseH (22, 23) to generate a nascent 3′ end capable of annealing to the complementary sequence on the 5′ end of the (−) strand DNA (Fig. 1d). If (+) strand DNA synthesis were to proceed beyond the m1A58 position, replicating the rest of the tRNA, strand transfer could presumably occur, but the extended 3′ end could not anneal to the complementary sequence in the (−) strand. Therefore, the 3′ end might not serve to prime further elongation to produce a double-stranded DNA molecule for integration into the host chromosome.

In this report, we compare natural tRNA3Lys containing posttranscriptional modifications to synthetic tRNA3Lys without modifications for their ability to terminate synthesis and generate an authentic (+) strand strong stop DNA intermediate and to provide a 3′ terminus that can efficiently prime replication after (+) strand transfer has occurred. Our findings suggest that the m1A posttranscriptional modification present 19 nt from the 3′ end of cellular tRNAs that prime retroviral (−) strand DNA synthesis is required for termination of (+) strand synthesis at the appropriate site. Without proper termination, post-strand-transfer replication does not occur.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Pure heterodimeric (p66/p51) RT from HIV was kindly provided by A. West of our laboratory. Pure RT from MMLV and AMV were purchased from GIBCO/BRL and Promega, respectively. T4 DNA kinase and T4 DNA ligase were from Boehringer Mannheim.

Preparation of Nucleic Acid Substrates.

DNA oligonucleotides were produced by the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center Oligonucleotide Core Facility on a Millipore nucleic acid synthesizer. The sequences of the DNA oligonucleotides used in this study are as follows: the DNA 18-nt equivalent of the 3′ sequence of tRNA3Lys, 5′-GTCCCTGTTCGGGCGCCA-3′; the 24-nt primer of (+) strand synthesis, 5′-CGGAGACTCTGGTAACTAGACATC-3′; the 46-nt bridge, 5′-GTCAGTGTGGAAAAATCTCTAGCAGTGGCGCCCGAACAGGGACTTG-3′, used to enable ligation of the 76-mer 5′-CTGCTAGAGATTTTTCCACACTGACTAAAAGGGTCTGATTGATGTCTAGTTACCAGAGTCTCCGCCCGTTTCTTTT-3′ with tRNA3Lys or the 18-mer; and the 60-nt recipient strand transfer template 5′-CCTGCGTCGAGAGAGCTCCTCTGGTTCTACTTTCGCTTTCGCGTCCCTGTTCGGGCGCCA-3′. Oligonucleotides were purified by denaturing ion exchange chromatography on a 1-ml MonoQ (Pharmacia) column in a buffer containing 20 mM NaOH and 1 mM EDTA and eluted with a NaCl gradient. Purified oligonucleotides were then desalted on Sep-Pak Cartridges (Millipore). Purified natural and synthetic tRNA3Lys were kindly provided by R. Thimmig of our laboratory (unpublished work).

To create templates that approximate the (−) strand covalently linked to the priming tRNA, the 5′ end of the 76-base oligonucleotide was first phosphorylated by T4 DNA kinase. Equimolar amounts of phosphorylated 76-base oligonucleotide and the 18-base oligonucleotide, the natural tRNA3Lys, or the synthetic tRNA3Lys were annealed to the 46-base bridging oligonucleotide in 100 mM NaCl by heating for 3 min at 93°C followed by cooling over a 60-min period to 30°C. Templates were annealed to the 46-nt bridge, with ligation catalyzed by 0.5 units/μl of T4 DNA ligase at room temperature for 48 h, and purified by electrophoresis on denaturing polyacrylamide gels. After further purification by ion exchange chromatography on a 1-ml MonoQ column to remove any contaminating polyacrylamide, templates were dialyzed into 10 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7) and 1 mM EDTA by using 3.5-kDa cutoff dialysis tubing (11.5-mm diameter Spectra/Por) that had been soaked in a 0.1% diethylpyrocarbonate solution for 12 h at 37°C and then boiled for 20 min. Concentrations of DNA oligonucleotides were determined spectrophotometrically at 260 nm by using extinction coefficients of 1 OD = 33 μg/ml for single-stranded DNA and 1 OD = 37 μg/ml for the mixed DNA/tRNA templates. The 24-nt primer was 5′ end-labeled with 0.1 mCi (4,500 Ci/mmol; 1 Ci = 37 GBq) of [γ-32P]ATP (ICN) and T4 DNA kinase to a specific activity of 0.01 μCi/pmol. Unincorporated [γ-32P]ATP was removed by the Sep-Pak Cartridge.

Standard Reaction Conditions.

Replication reactions were conducted by addition of 0.1 pmol of RT from HIV, MMLV, or AMV to 2 pmol of templates a, b, or c (see Fig. 2A) in 40 μl of 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.1), 2 mM MgCl2, 200 mM potassium glutamate, 8 mM DTT, 0.05% Triton X-100, and 15 μM each dATP, dGTP, dCTP, and dTTP. For strand transfer reactions, 2 pmol of recipient template was added.

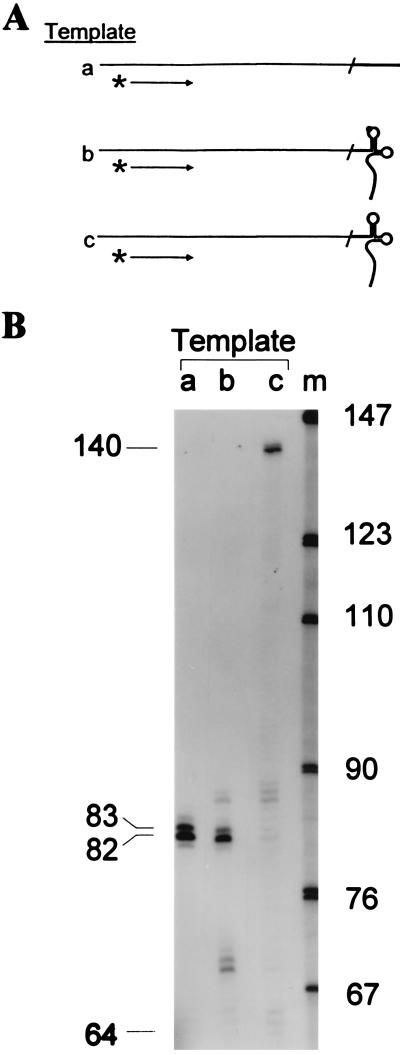

Figure 2.

Only templates containing natural tRNA3Lys with base modifications signal termination of reverse transcription to generate the authentic (+) strand strong stop DNA intermediate. (A) A 76-base DNA oligonucleotide was ligated to the 3′ ends of either an 18-base DNA oligonucleotide, natural tRNA3Lys, or synthetic tRNA3Lys by an oligonucleotide bridge resulting in templates containing 18 DNA nt on the 5′ end of the template identical to the 3′ end of tRNA3Lys (template a); the natural tRNA3Lys with m1A58 and other naturally modified bases (template b); and synthetic tRNA3Lys with no base modifications (template c). Plus-strand synthesis was primed on each template with a 32P-end-labeled 24-nt primer annealed nucleotide from the template 3′ end and initiated by addition of RT, Mg2+, and dNTPs. Reaction mixtures were incubated for 10 min at 37°C and synthesis was stopped by the addition of EDTA to 50 mM (final concentration). (B) Samples for each reaction were subjected to electrophoresis on an 8 M urea/7% polyacrylamide sequencing gel. The gel was dried and exposed to x-ray film. Lanes a, b, and c show the products of reactions using templates a, b, and c, respectively. The size in nucleotides of the products generated with the labeled primer are shown on the left. Position of products expected from termination at the ligation junction between the 76-base DNA oligonucleotide and tRNA3Lys sequences at 64 nt is also indicated. Positions of bands were determined relative to a sequencing ladder run in parallel (data not shown). Size standards (lane m; MspI-digested pBR322) are shown.

RESULTS

Posttranscriptional Modification of tRNA3Lys Is Essential for Generation of the (+) Strand Strong Stop DNA Intermediate.

To experimentally test the hypothesis that the m1A58 modification in the priming tRNA is necessary for the production of the (+) strand strong stop DNA intermediate, we created templates that mimic those used in the natural reaction (Fig. 1c). Three different templates were created by ligating a 76-nt DNA to an 18-base DNA oligonucleotide (Fig. 2A, template a), natural tRNA3Lys (the HIV-1 primer; template b), or synthetic, unmodified tRNA3Lys (template c). The 38 nt adjacent to the tRNA3Lys sequence are identical to the authentic viral template.

A 5′ 32P-end-labeled 24-nt DNA primer was annealed 12 nt from the 3′ end of all three templates (Fig. 2A) and extended with HIV-1 RT. Analysis of products by denaturing gel electrophoresis (Fig. 2B) permitted determination of the replication termination sites. On template b, containing natural tRNA3Lys, the major 82-nt product resulted from replication of only the first 18 nt of the tRNA binding site (Fig. 2B, lane b), thus regenerating the primer binding site and reproducing the (+) strand strong stop product formed in vivo. When the products were analyzed with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics), over 65% of the elongated primer terminated one base before the m1A58. In contrast, the entire tRNA molecule was replicated when template c, containing synthetic tRNA3Lys without base modifications, was used, generating a 140-nt product (Fig. 2B, lane c); no product that terminated one base before the A58 position was detected. Replication of DNA template a yielded an 82-nt product (Fig. 2B, lane a) that reflected replication of the entire template and also products resulting from the addition of bases in a non-template-directed reaction typical of many polymerases (24). Additional minor bands present beyond the point of termination in the reaction with template b may also represent addition of nucleotides in a non-template-directed reaction similar to that seen for template a and for the (−) strand transfer reaction (3). Minor bands seen before the point of termination may be caused by RT stalling due to specific sequence elements, secondary structure, or distributive synthesis (25, 26). These results demonstrate that a posttranscriptional modification, presumably m1A58 in natural tRNA3Lys, is a required signal for generation of the (+) strand strong stop DNA intermediate.

Posttranscriptional Modification of tRNA3Lys Is Essential for Replication After (+) Strand Transfer.

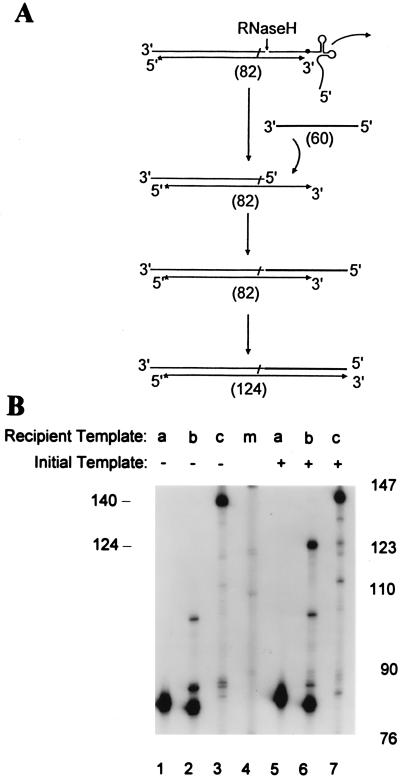

Once RT replicates the primer binding site, RNaseH should cleave the tRNA3Lys from both templates b and c to provide a sequence (T) that can anneal to a recipient template containing a complementary sequence generated during (−) strand DNA synthesis (Fig. 1 d and e). This would provide an accessible single-stranded primer binding site that could anneal to the exposed complementary (−) strand sequence, enabling strand transfer and continued replication. We investigated this possibility by adding a recipient strand transfer template that is identical to the first 60 nt of the natural HIV recipient for (+) strand transfer (Fig. 3A), as described in Materials and Methods. A specific product of 124 nt was observed in the reaction containing both template b and the recipient template (Fig. 3B, compare lanes 6 and 2), whereas reactions containing template a or c yielded the same products as did reactions lacking the recipient template (Fig. 3B, compare lanes 5 vs. 1 and lanes 7 vs. 3). The product formed on template a, a fully DNA template, is resistant to RNaseH, precluding strand transfer and providing further evidence that RNaseH cleavage is required to enable (+) strand transfer. Products formed on template c likely yield a single-stranded primer binding site that strand-transfers to the recipient template, but since replication proceeded 58 nt beyond the proper termination site, its 3′ end is not complementary to the template, and it cannot serve to prime further synthesis. Therefore, only reactions containing template b with the m1A58 modification yield a 3′ end that can strand-transfer and serve to prime further (+) strand synthesis on the recipient template.

Figure 3.

Plus-strand transfer and elongation. (A) When the (+) strand intermediate is synthesized (82 nt long), replication terminates. A recipient strand transfer template (60 nt long) added to the reaction anneals to the 3′ end of the (+) strand intermediate and serves as a template for further synthesis to generate a 124-nt product. (B) For strand transfer and elongation reactions, a 60-nt recipient strand transfer template was added along with the initial templates a, b, or c in lanes 5–7, respectively. Reactions lacking the recipient template are shown for comparison in lanes 1–3. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 15 min at 37°C, subjected to electrophoresis, and exposed to x-ray film. Size standards (lane m) are shown for comparison.

The Termination Signal for Generation of the (+) Strand Strong Stop Intermediate and Post-Strand-Transfer Replication Is Recognized by Noncognate RT.

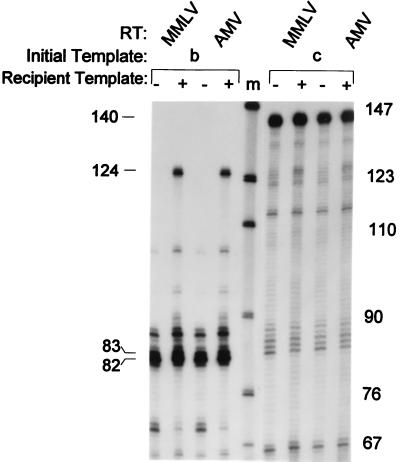

Since all retroviral tRNA primers contain m1A 19 nt from their 3′ ends (1), we asked whether other retroviral RTs would generate a (+) strand strong stop intermediate and elongated strand transfer product on our model HIV templates. The reactions were repeated by using RTs from MMLV and AMV. Both RTs produced the proper 82-nt (+) strand strong stop intermediate on template b, containing natural tRNA3Lys, but not template c (Fig. 4). When the recipient strand-transfer template was added to these reactions, RT from MMLV and AMV also synthesized the expected 124-nt strand transfer product only in reactions containing template b (Fig. 4), consistent with the results obtained with HIV RT. This indicates that the signal found in the primer for HIV reverse transcription, m1A58 in tRNA3Lys, is a general one recognized by noncognate RTs, consistent with the presence of m1A at the (+) strand strong stop termination site in all retroviral primers. Presumably, the m1A modification on retroviral tRNA primers acts to stall or destabilize replication during (+) strand synthesis, resulting in the generation of the (+) strand strong stop DNA intermediate.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the (+) strand intermediate and strand transfer products produced by MMLV and AMV RT. RT from MMLV and AMV was added to reactions containing templates b and c in the presence and absence of recipient strand transfer template. All reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 min at 37°C, and samples were processed, subjected to electrophoresis, and exposed to x-ray film. Size standards (lane m) are shown for comparison.

DISCUSSION

Several studies have demonstrated the generation of the (+) strand strong stop DNA intermediate upon addition of deoxynucleoside triphosphates to a preparation of disrupted MMLV (1, 2, 11). Goff and colleagues (20) demonstrated that the (+) strand MMLV intermediate generated in vivo stops precisely after replication of the first 18 3′ nucleotides of tRNA primer. Like all tRNA primers for replicative retroviruses, the primer for MMLV contains m1A58, a modification that has been suggested as the signal that causes replication termination and generation of the (+) strand strong stop DNA intermediate (1). Efficient use of tRNA3Lys as a primer, interaction of the anticodon loop of tRNA3Lys with the RNA genome, and the switch from initiation to an elongation complex for synthesis of the (−) strand all require posttranscriptional modifications of tRNA3Lys (27–29). In this report, we experimentally demonstrate the importance of posttranscriptional modifications in generating a (+) strand strong stop DNA intermediate of proper length, and in subsequent elongation of the (+) strand after strand transfer.

The (+) strand strong stop DNA intermediate for HIV DNA replication was synthesized by using model DNA/tRNA templates containing a (−) strand DNA ligated to either natural tRNA3Lys with posttranscriptional modifications or synthetic tRNA3Lys lacking modifications. Plus-strand synthesis catalyzed by RT was primed from an oligonucleotide annealed to a (−) strand DNA. Proper termination one base before the m1A58 modification generated the (+) strand strong stop DNA intermediate only on templates containing the natural tRNA3Lys sequence. The m1A58 modification cannot form a standard Watson–Crick base pair because of the methyl group at the N-1 position, which presumably destabilizes elongation of the (+) strand and leads to termination. Therefore, synthesis would terminate one base before the m1A58 at G59, exactly 18 nt from the 3′ end of the tRNA primer. Although the template with the natural tRNA3Lys contains other posttranscriptional modifications, termination occurred mostly opposite the G59 position (Fig. 2B). A small amount of read-through synthesis terminated at a pseudouridine at position 55 in tRNA3Lys.

After synthesis is terminated to produce the (+) strand strong stop intermediate, the tRNA primer must be removed to allow annealing of the nascent 3′ terminus (T) to (T′), permitting strand transfer and synthesis of the entire (+) strand (Figs. 1 d and e and 3A). A strand transfer product was only generated when the recipient template was added to reactions containing the modified tRNA3Lys (Fig. 3B), but not with the fully DNA template, a result consistent with the requirement for RNaseH activity in strand transfer. Because 18 nt of tRNA sequence are replicated and approximately 18 nt separate the polymerase and RNaseH active sites (30, 31), cleavage is expected to occur near or at the junction of the DNA/tRNA sequence. Cleavage on model substrates has been found to occur one base from the junction, leaving a single 3′ AMP attached to the DNA (23). The cleaved tRNA dissociates, permitting annealing of the recipient template to the 3′ terminus of the (+) strand intermediate and, in turn, further replication and completion of (+) strand synthesis. Cleavage of the template containing unmodified tRNA3Lys and strand transfer probably also occurs, but no full-length (+) strand product was observed (Fig. 3B). On templates containing unmodified tRNA, replication proceeds 58 nt beyond the point of normal termination; the newly formed 3′ end is not complementary to the recipient template and cannot efficiently prime further (+) strand synthesis.

Other posttranscriptional modifications or factors may aid in formation of the (+) strand strong stop DNA intermediate and in post-strand-transfer replication. Structures that encourage pausing facilitate strand transfer (32). Viral structures or exogenous factors may enhance the in vivo efficiency of strand transfer proceeding from products paused at m1A58. However, given the general nature of the specific termination 1 nt before m1A58, a modified base that cannot form a standard Watson–Crick base pair, and the ubiquity of this modification in tRNAs that prime retroviral replication, it appears that m1A is likely the primary determinant for termination of the (+) strand intermediate.

HIV is highly mutable and, because of the large number of replication cycles that occur within a single individual, is subject to extraordinary genetic variation in response to selective pressure (33). This is caused, in part, by the lack of an editing function in retroviral RTs and is also due to a very low fidelity of base incorporation, particularly in the context of certain sequences (34). Consequently, HIV clones resistant to drugs such as AZT (3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine) (35–37) and non-nucleoside RT inhibitors (38, 39) have emerged. Combination therapy with nucleoside and non-nucleoside inhibitors has also led to the appearance of virus with multi-drug-resistant RT (40). Antiretroviral therapy treatments that target HIV protease in combination with nucleoside inhibitors have been more effective than the inhibitors alone in reducing viral load in infected individuals to nondetectable levels.* However, mutations that confer resistance to protease inhibitors also occur (41).

Our work demonstrating a requirement for the posttranscriptional modification m1A58 of tRNAs that prime retroviral synthesis in generating the (+) strand strong stop DNA intermediate and post-strand-transfer replication implicates tRNA A58 adenine N-1 methyl transferase as a potential target for anti-HIV chemotherapeutic intervention. A highly proliferative rat adenocarcinoma cell line that lacks or has greatly diminished levels of this enzyme has been described (42), suggesting that tRNA A58 methylation is not essential for cell viability. This is consistent with biochemical studies that demonstrated that A58 → G substitutions are tolerated without significant effect upon aminoacylation kinetics (43) or participation in protein biosynthesis (44). This apparent dispensability of the methyl transferase, together with an expected lower mutability and lack of positive selective pressure favoring host mutants, might make it a superior target for chemotherapeutic intervention. A specific inhibitor of the tRNA A58 adenine N-1 methyl transferase should cause a block in HIV reverse transcription by inhibiting the generation of the proper (+) strand strong stop intermediate and hence post-strand-transfer replication.

After this paper was submitted for initial review, a report by Ben-Artzi et al. (45) made similar conclusions. In their system, a (+) strand primer was added to an endogenous (−) strand strong stop reaction where the (−) strand DNA template was generated from (+) strand RNA by HIV RT and modified or unmodified tRNA3Lys primers. In their system, unlike ours, significant termination of replication occurred within the primer binding site sequences. Also, Ben-Artzi et al. did not observe a requirement for A58 methylation for (+) strand transfer to occur, presumably because of the pausing and inefficient readthrough observed. The source of this discrepancy might be due to intra- or interstrand structures formed in their complex reaction mixtures. Yusupova and coworkers (46) recently observed that the ability of HIV RT to read into a tRNA was largely influenced by the identity of nucleic acids annealed to it. Due to the way Ben-Artzi and coworkers generated their substrates, RNA was probably still annealed to the 3′ 18 nt of tRNA3Lys, making the process of reverse transcription a strand-displacement reaction. Yusupova et al. showed that tRNA3Lys can be recognized differently by RT, depending on the nature of the oligonucleotide hybridized to its 3′ terminus. An RNA oligonucleotide hybridized to the tRNA 3′ terminus specifies the tRNA to be used as a primer: the annealed oligonucleotide is not elongated. In contrast, an annealed DNA oligonucleotide is preferentially used as a primer. They also showed that an RNA oligonucleotide supported full reverse transcription of unmodified tRNA (46). It is not clear how annealed RNA would influence pausing of reverse transcriptase in a strand displacement reaction. These differences indicate the need for further investigation of A58 methylation on the course of HIV replication in biochemical and cellular contexts to establish whether methylation alone is sufficient to signal proper termination of (+) strand strong stop synthesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Anthony West and Roberta Thimmig for providing material and advice. This work is supported by National Institutes of Health Grant 5 RO1 AI26600 and by National Institutes of Health Fellowship 1F32 AI09171.

ABBREVIATIONS

- m1A58

1-methyl-A58

- MMLV

Moloney murine leukemia virus

- AMV

avian myoblastosis virus

- RT

reverse transcriptase

Footnotes

Gulick, R., Mellors, J., Havlir, D., Eron, J., Gonzalez, C., McMahon, D., Richman, D., Valentine, F., Jonas, L., Meibohm, A., Chiou, R., Deutsch, P., Emini, E. & Chodakewitz, J., Third Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Feb. 28–Mar. 1, 1996, Washington, DC, p. 162, abstr. LB 7.

References

- 1.Gilboa E, Mitra S W, Goff S, Baltimore D. Cell. 1979;18:93–100. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90357-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitra S W, Goff S, Gilboa E, Baltimore D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4355–4359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peliska J A, Benkovic S J. Science. 1992;258:1112–1118. doi: 10.1126/science.1279806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faras A J, Taylor J M, Levinson W E, Goodman H M, Bishop J M. J Mol Biol. 1973;79:163–183. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90277-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor J M, Illmensee R. J Virol. 1975;16:553–558. doi: 10.1128/jvi.16.3.553-558.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor J M. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1977;473:57–71. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(77)90007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ratner L, Haseltine W, Patarca R, Livak K, Starcish B, Josephs S, Doran E, Ragfalski J, Whitehorn E, Baumeister K, Ivanoff L, Petteway S, Jr, Pearson M, Lautenberger J, Papas T, Ghrayeb J, Chang N, Gallo R, Wong-Staal F. Nature (London) 1985;313:277–284. doi: 10.1038/313277a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harada F, Sawyer R C, Dalhberg J E. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:3487–3497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cordell B, Stavnezer E, Friedrich R, Bishop J M, Goodman H M. J Virol. 1976;19:548–558. doi: 10.1128/jvi.19.2.548-558.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harada F, Peters G G, Dalhberg J E. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:10979–10985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitra S W, Chow M, Champoux J, Baltimore D. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:5983–5986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charneau P, Clavel F. J Virol. 1991;65:2415–2421. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2415-2421.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hugnes O, Tjotta E, Grinde B. Arch Virol. 1991;116:133–141. doi: 10.1007/BF01319237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith J K, Cywinski A, Taylor J M. J Virol. 1984;49:200–204. doi: 10.1128/jvi.49.1.200-204.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finston W I, Champoux J J. J Virol. 1984;51:26–33. doi: 10.1128/jvi.51.1.26-33.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Champoux J J, Gilboa E, Baltimore S. J Virol. 1984;49:686–691. doi: 10.1128/jvi.49.3.686-691.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Resnick R, Omar C A, Faras A J. J Virol. 1984;51:813–821. doi: 10.1128/jvi.51.3.813-821.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boone L R, Skalka A M. J Virol. 1981;37:109–116. doi: 10.1128/jvi.37.1.109-116.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huber H E, Richardson C C. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:10565–10573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roth M J, Schwartzberg P L, Goff S P. Cell. 1989;58:47–54. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90401-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Varmus H E, Heasley S, Kung H J, Oppermann H, Smith V C, Bishop J M, Shank P R. J Mol Biol. 1978;120:55–82. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90295-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Omar C A, Faras A J. Cell. 1982;30:797–805. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furfine E S, Reardon J E. Biochemistry. 1991;30:7041–7046. doi: 10.1021/bi00243a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clark J M. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:9677–9686. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.20.9677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klarmann G J, Schauber C A, Preston B D. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:9793–9802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abbotts J, Bebenek K, Kunkel T A, Wilson S H. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:10312–10323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Isel C, Marquet R, Keith G, Ehresmann C, Ehresmann B. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:25269–25272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Isel C, Ehresmann C, Keith G, Ehresmann B, Marquet R. J Mol Biol. 1995;247:236–250. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Isel C, Lanchy J M, LeGrice S F J, Ehresmann C, Ehresmann B, Marquet R. EMBO J. 1996;15:917–924. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohlstaedt L A, Wang J, Friedman J M, Rice P A, Steitz T A. Science. 1992;256:1783–1790. doi: 10.1126/science.1377403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gopalakrishnan V, Peliska J A, Benkovic S J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10763–10767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu W, Bluimberg B M, Fay P J, Bambera R A. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:325–332. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.1.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coffin J M. Science. 1995;267:483–489. doi: 10.1126/science.7824947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bebenek K, Kunkel T A. In: Reverse Transcriptase. Skalka A M, Goff S P, editors. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1993. pp. 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larder B A, Darby G, Richman D D. Science. 1989;243:1731–1734. doi: 10.1126/science.2467383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larder B A, Kemp S D. Science. 1989;246:1155–1158. doi: 10.1126/science.2479983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boucher C A B, O’Sullivan E, Mulder J W, Ramautarsing C, Kellam P, Darby G, Lange J M A, Goudsmit J, Larder B A. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:105–110. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Richman D, Shih C K, Lowy I, Rose J, Prodanovich P, Goff S, Griffin J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:11241–11245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nunberg J H, Schleif W A, Boots E J, O’Brien J A, Quintero J C, Hoffman J M, Emini E A, Goldman M E. J Virol. 1991;65:4887–4892. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.9.4887-4892.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Larder B A, Kellam P, Kemp S D. Nature (London) 1993;365:451–453. doi: 10.1038/365451a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Condra J H, Schleif W A, Blahy O M, Gabryelski L J, Graham D J, Quintero J C, Rhodes A, Robbins H L, Roth E, Shivaprakash M, Titus D, Yang T, Teppler H, Squires K E, Deutsch P J, Emini E A. Nature (London) 1995;374:569–571. doi: 10.1038/374569a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hansen J, Schulze T, Moelling K J. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:12393–12396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sampson J R, DiRenzo A B, Behlen L S, Uhlenbeck O C. Biochemistry. 1990;29:2523–2532. doi: 10.1021/bi00462a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nazarenko I A, Harrington K M, Uhlenbeck O C. EMBO J. 1994;13:2464–2471. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06531.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ben-Artzi H, Shemesh J, Zeelon E, Amit B, Kleiman L, Gorecki M, Panet A. Biochemistry. 1996;35:10549–10557. doi: 10.1021/bi960439x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yusupova G, Janchy J, Yusupov M, Keith G, Le Grice S, Ehresmann C, Ehresmann B, Marquet R. J Mol Biol. 1996;261:315–321. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]