Abstract

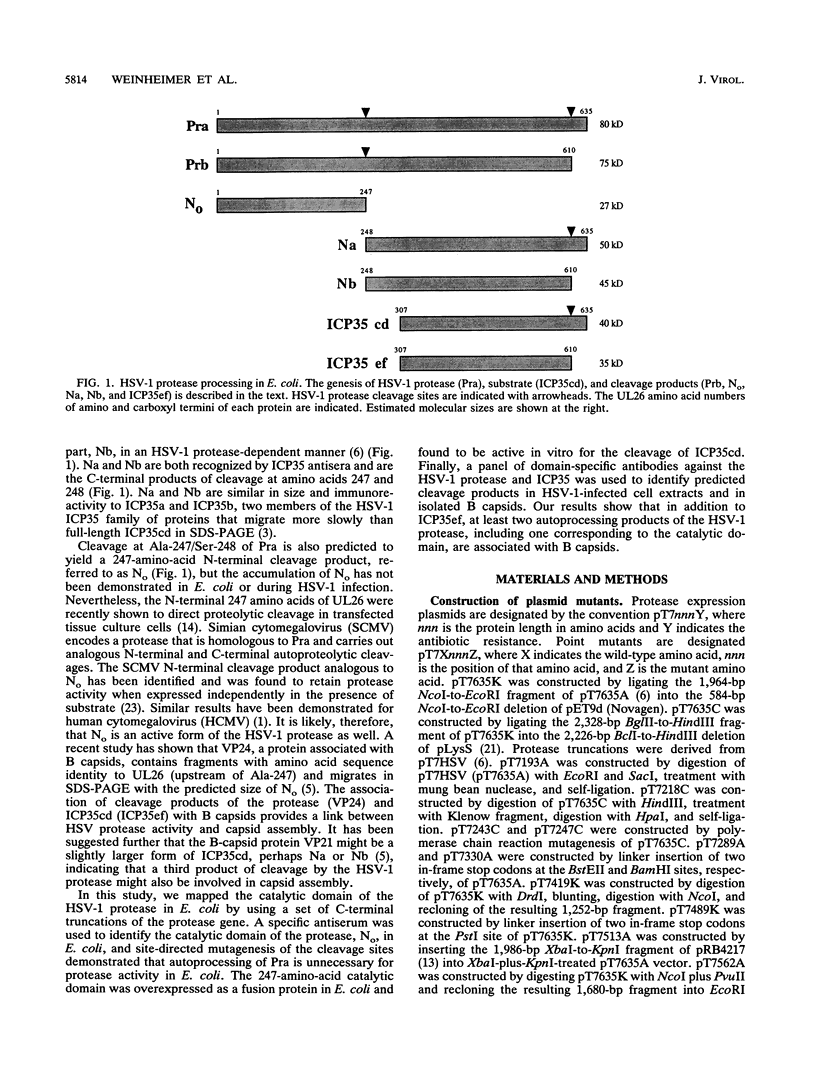

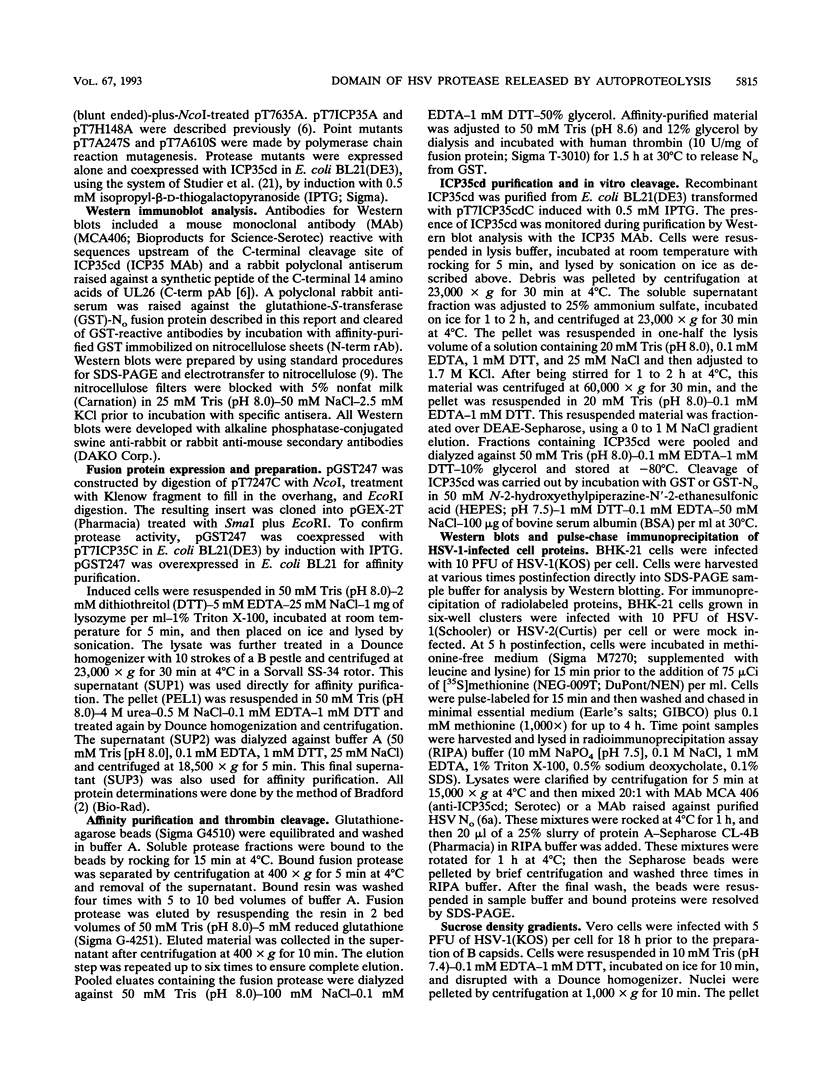

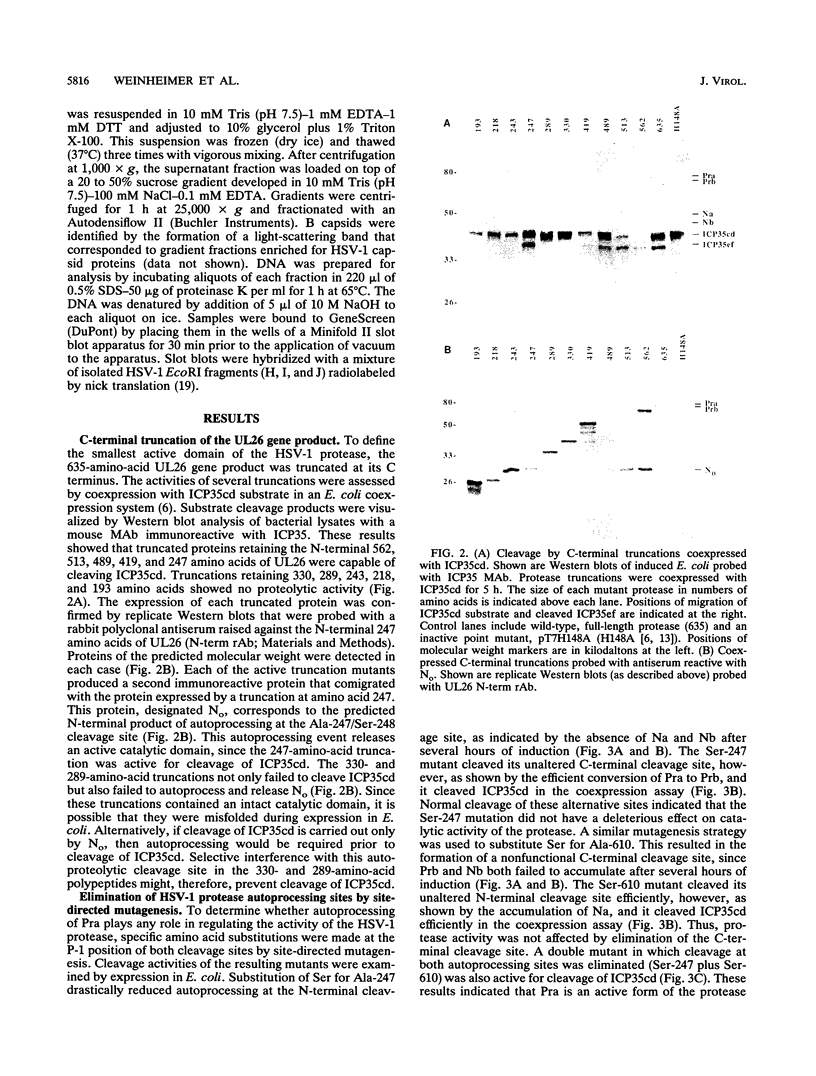

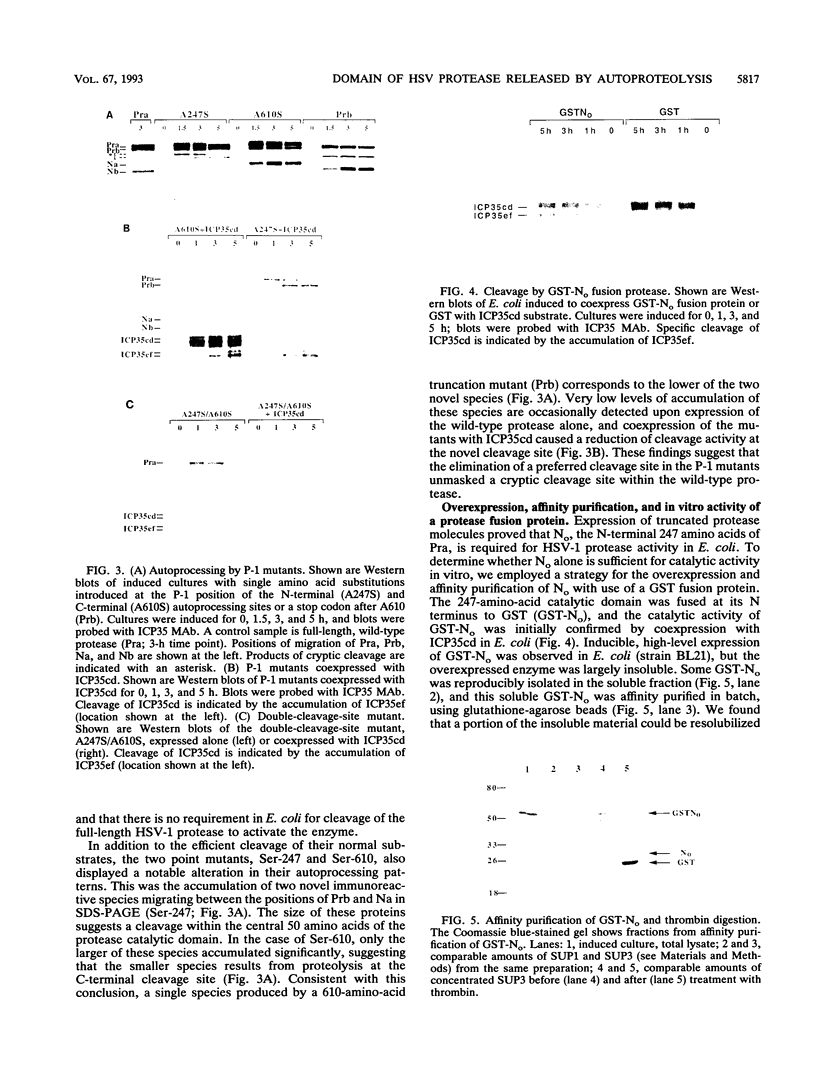

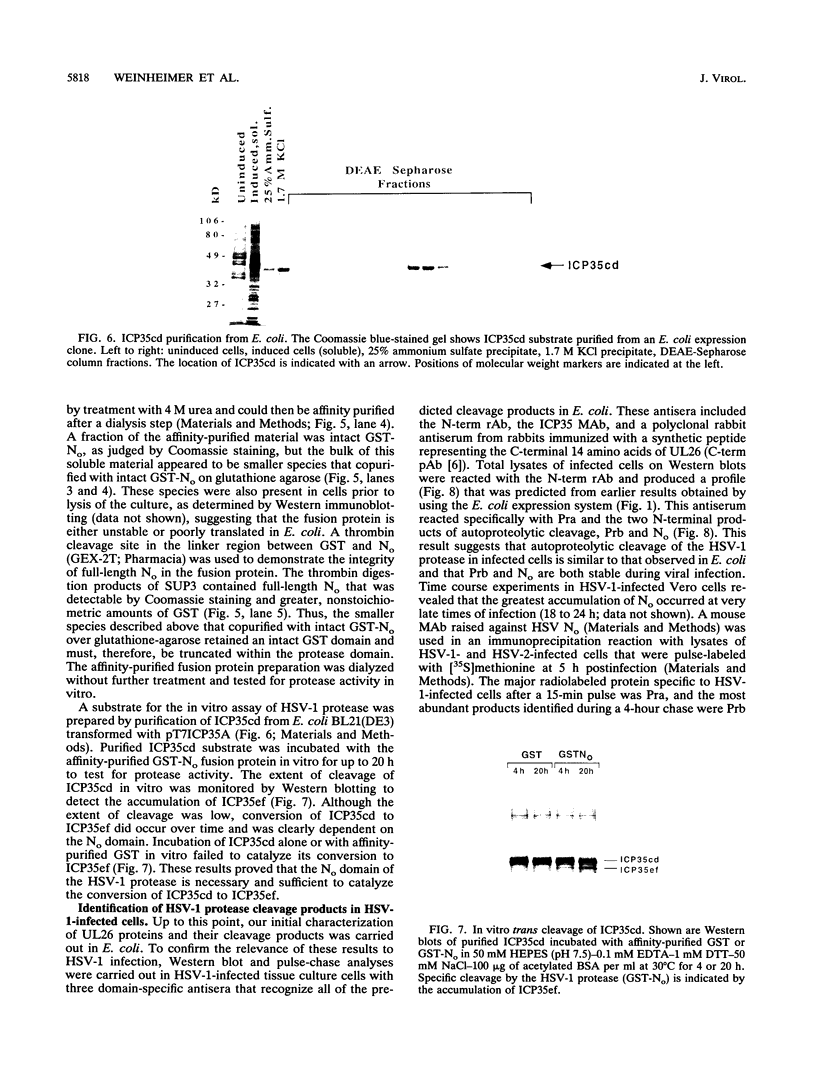

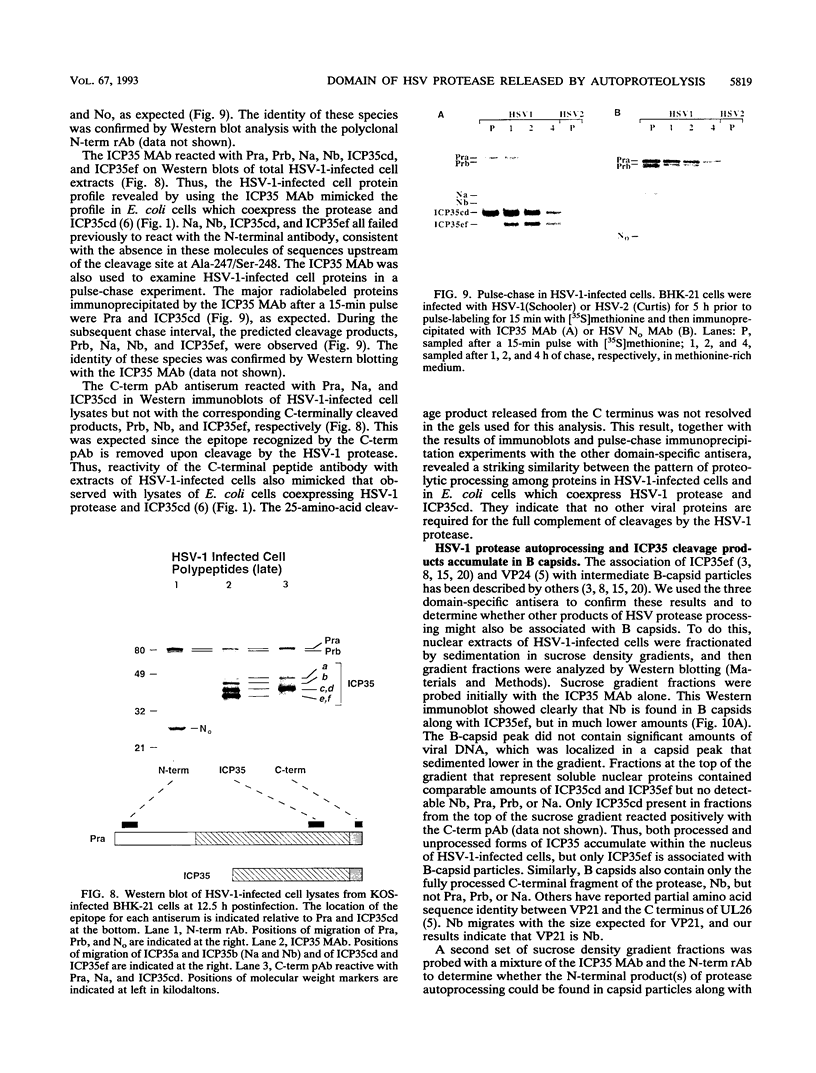

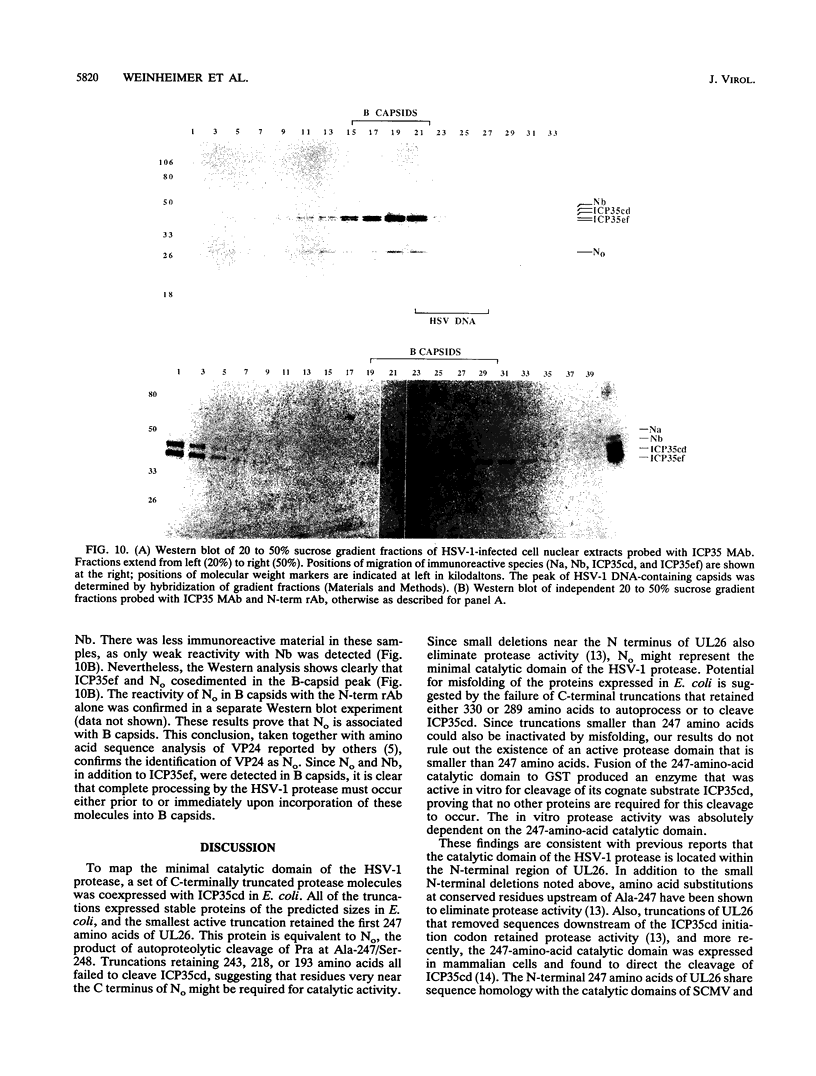

The UL26 gene of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) encodes a 635-amino-acid protease that cleaves itself and the HSV-1 assembly protein ICP35cd (F. Liu and B. Roizman, J. Virol. 65:5149-5156, 1991). We previously examined the HSV protease by using an Escherichia coli expression system (I. C. Deckman, M. Hagen, and P. J. McCann III, J. Virol. 66:7362-7367, 1992) and identified two autoproteolytic cleavage sites between residues 247 and 248 and residues 610 and 611 of UL26 (C. L. DiIanni, D. A. Drier, I. C. Deckman, P. J. McCann III, F. Liu, B. Roizman, R. J. Colonno, and M. G. Cordingley, J. Biol. Chem. 268:2048-2051, 1993). In this study, a series of C-terminal truncations of the UL26 open reading frame was tested for cleavage activity in E. coli. Our results delimit the catalytic domain of the protease to the N-terminal 247 amino acids of UL26 corresponding to No, the amino-terminal product of protease autoprocessing. Autoprocessing of the full-length protease was found to be unnecessary for catalysis, since elimination of either or both cleavage sites by site-directed mutagenesis fails to prevent cleavage of ICP35cd or an unaltered protease autoprocessing site. Catalytic activity of the 247-amino-acid protease domain was confirmed in vitro by using a glutathione-S-transferase fusion protein. The fusion protease was induced to high levels of expression, affinity purified, and used to cleave purified ICP35cd in vitro, indicating that no other proteins are required. By using a set of domain-specific antisera, all of the HSV-1 protease cleavage products predicted from studies in E. coli were identified in HSV-1-infected cells. At least two protease autoprocessing products, in addition to fully processed ICP35cd (ICP35ef), were associated with intermediate B capsids in the nucleus of infected cells, suggesting a key role for proteolytic maturation of the protease and ICP35cd in HSV-1 capsid assembly.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976 May 7;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun D. K., Roizman B., Pereira L. Characterization of post-translational products of herpes simplex virus gene 35 proteins binding to the surfaces of full capsids but not empty capsids. J Virol. 1984 Jan;49(1):142–153. doi: 10.1128/jvi.49.1.142-153.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casjens S., King J. Virus assembly. Annu Rev Biochem. 1975;44:555–611. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.44.070175.003011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison M. D., Rixon F. J., Davison A. J. Identification of genes encoding two capsid proteins (VP24 and VP26) of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Gen Virol. 1992 Oct;73(Pt 10):2709–2713. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-10-2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deckman I. C., Hagen M., McCann P. J., 3rd Herpes simplex virus type 1 protease expressed in Escherichia coli exhibits autoprocessing and specific cleavage of the ICP35 assembly protein. J Virol. 1992 Dec;66(12):7362–7367. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7362-7367.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiIanni C. L., Drier D. A., Deckman I. C., McCann P. J., 3rd, Liu F., Roizman B., Colonno R. J., Cordingley M. G. Identification of the herpes simplex virus-1 protease cleavage sites by direct sequence analysis of autoproteolytic cleavage products. J Biol Chem. 1993 Jan 25;268(3):2048–2051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson W., Roizman B. Proteins specified by herpes simplex virus. 8. Characterization and composition of multiple capsid forms of subtypes 1 and 2. J Virol. 1972 Nov;10(5):1044–1052. doi: 10.1128/jvi.10.5.1044-1052.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. Y., Irmiere A., Gibson W. Primate cytomegalovirus assembly: evidence that DNA packaging occurs subsequent to B capsid assembly. Virology. 1988 Nov;167(1):87–96. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F. Y., Roizman B. The herpes simplex virus 1 gene encoding a protease also contains within its coding domain the gene encoding the more abundant substrate. J Virol. 1991 Oct;65(10):5149–5156. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.10.5149-5156.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F. Y., Roizman B. The promoter, transcriptional unit, and coding sequence of herpes simplex virus 1 family 35 proteins are contained within and in frame with the UL26 open reading frame. J Virol. 1991 Jan;65(1):206–212. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.1.206-212.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F., Roizman B. Characterization of the protease and other products of amino-terminus-proximal cleavage of the herpes simplex virus 1 UL26 protein. J Virol. 1993 Mar;67(3):1300–1309. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.3.1300-1309.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F., Roizman B. Differentiation of multiple domains in the herpes simplex virus 1 protease encoded by the UL26 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Mar 15;89(6):2076–2080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb W. W., Brown J. C. Structure of the herpes simplex virus capsid: effects of extraction with guanidine hydrochloride and partial reconstitution of extracted capsids. J Virol. 1991 Feb;65(2):613–620. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.2.613-620.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb W. W., Brown J. C. Use of Ar+ plasma etching to localize structural proteins in the capsid of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Virol. 1989 Nov;63(11):4697–4702. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.11.4697-4702.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston V. G., Coates J. A., Rixon F. J. Identification and characterization of a herpes simplex virus gene product required for encapsidation of virus DNA. J Virol. 1983 Mar;45(3):1056–1064. doi: 10.1128/jvi.45.3.1056-1064.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman G., Bachenheimer S. L. Characterization of intranuclear capsids made by ts morphogenic mutants of HSV-1. Virology. 1988 Apr;163(2):471–480. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90288-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studier F. W., Rosenberg A. H., Dunn J. J., Dubendorff J. W. Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:60–89. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch A. R., Woods A. S., McNally L. M., Cotter R. J., Gibson W. A herpesvirus maturational proteinase, assemblin: identification of its gene, putative active site domain, and cleavage site. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Dec 1;88(23):10792–10796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]