Abstract

Protein translocation into peroxisomes takes place via recognition of a peroxisomal targeting signal present at either the extreme C termini (PTS1) or N termini (PTS2) of matrix proteins. In mammals and yeast, the peroxisomal targeting signal receptor, Pex5p, recognizes the PTS1 consisting of -SKL or variants thereof. Although many plant peroxisomal matrix proteins are transported through the PTS1 pathway, little is known about the PTS1 receptor or any other peroxisome assembly protein from plants. We cloned tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) cDNAs encoding Pex5p (NtPEX5) based on the protein’s interaction with a PTS1-containing protein in the yeast two-hybrid system. Nucleotide sequence analysis revealed that the tobacco Pex5p contains seven tetratricopeptide repeats and that NtPEX5 shares greater sequence similarity with its homolog from humans than from yeast. Expression of NtPEX5 fusion proteins, consisting of the N-terminal part of yeast Pex5p and the C-terminal region of NtPEX5, in a Saccharomyces cerevisiae pex5 mutant restored protein translocation into peroxisomes. These experiments confirmed the identity of the tobacco protein as a PTS1 receptor and indicated that components of the peroxisomal translocation apparatus are conserved functionally. Two-hybrid assays showed that NtPEX5 interacts with a wide range of PTS1 variants that also interact with the human Pex5p. Interestingly, the C-terminal residues of some of these peptides deviated from the established plant PTS1 consensus sequence. We conclude that there are significant sequence and functional similarities between the plant and human Pex5ps.

Plant peroxisomes are 0.2- to 1.8-μm organelles that are bounded by a single membrane and that characteristically contain hydrogen peroxide-generating oxidases and catalase (1). In higher plants, peroxisomes can be divided into at least three different classes based on their metabolic functions and the developmental state of the cells in which they are found (reviewed in refs. 1 and 2). Glyoxysomes are present primarily in germinating seedlings and contain enzymes responsible for fatty acid degradation. Leaf peroxisomes play roles in photorespiration in photosynthetically active tissues. In root nodules, metabolic reactions involved in nitrogen transport occur in peroxisomes. Although the physiology of plant peroxisomes has been studied extensively, little is known of the specific mechanisms that govern the biogenesis of this organelle.

Peroxisomal matrix proteins are translocated posttranslationally from the cytosol into the organelle (reviewed in refs. 2 and 3). Specific transport is mediated through at least two types of evolutionarily conserved peroxisomal targeting signals, PTS1 and PTS2 (reviewed in ref. 4). PTS1, initially defined by the prototypical tripeptide -SKL, is present at the extreme C terminus of peroxisomal proteins (5). A wide range of C-terminal tripeptide sequences has been shown to function as PTS1s in plants. For example, the motifs [A/C/P/S]-[K/R]-[I/L/M] and [A/C/G/S/T]-[H/K/L/N]-[I/L/M/Y], respectively, have been shown to function as PTS1s in transgenic plant (6) and transient expression experiments (7, 8). Thus, the translocation system of plant peroxisomes appears to accept a diversity of PTS1 variants. PTS2 is located at the N terminus of peroxisomal proteins and is defined by the loose consensus sequence -R-[L/I/Q]-X5-H-L- (reviewed in ref. 4). Similar sequences found at the N terminus of the plant peroxisomal proteins malate dehydrogenase, citrate synthase, and thiolase have been shown to function as PTS2 (9–11). Plant peroxisomal proteins containing PTS1 and PTS2 have been shown to be correctly targeted in other organisms such as yeast and mammals, suggesting that the transport mechanisms are conserved between kingdoms (9, 12).

Although plants possess several classes of peroxisomes, similar or identical components appear to be involved in the recognition and transport of their peroxisomal proteins. For example, glyoxysomes, leaf peroxisomes, and root peroxisomes are competent to import ectopically expressed glyoxysome-specific proteins (13, 14), and both glyoxysomal and leaf peroxisomal enzymes are colocalized in peroxisomes of cells undergoing the transition from postgerminative to vegetative growth (15, 16).

The PTS1 receptor, Pex5p (17), was identified in yeasts and humans and shown to interact directly with the PTS1 (reviewed in ref. 18). Pex5p contains seven tetratricopeptide repeats (TPR) in its C-terminal half that are necessary and sufficient for the interaction with PTS1 (19, 20). TPRs are degenerate 34-aa repeats postulated to function in protein–protein interactions (21). Recognition of PTS1 by Pex5p most likely takes place in the cytosol, and the cargo-loaded Pex5p complex is then thought to bind to the peroxisomal membrane proteins Pex13p and Pex14p (22–26). However, the mechanism by which matrix proteins are translocated into the organelle has not yet been defined. In vitro experiments using isolated plant peroxisomes suggest the existence of a plant PTS1 receptor similar to the human and yeast Pex5p (27, 28). However, no component of the peroxisome recognition and translocation machinery of plants had been identified.

To isolate the plant PTS1 receptor, a tobacco cDNA library was screened by using the yeast two-hybrid system, and cDNA clones were identified that encode proteins that interact with the PTS1. Nucleotide sequencing studies showed that the tobacco cDNA clones encoded a Pex5p homolog that shares greater sequence identity with human than with yeast Pex5p. The function of Nicotiana tabacum Pex5p (NtPEX5) as a PTS1 receptor was established by showing that the plant protein restored protein translocation into peroxisomes when expressed in a yeast pex5 deletion mutant. Two-hybrid assays showed that NtPEX5 interacts with PTS1 variants that are also recognized by its homolog from humans, suggesting both sequence and functional similarities between the plant and human Pex5ps.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid Constructions.

Standard cloning procedures were used for the construction of all plasmids (29). The nucleotide sequences of fragments produced by PCR mutagenesis were verified. A PCR strategy was used to obtain a plasmid encoding a fusion protein consisting of the Gal4p-binding domain and the C-terminal 274 residues of NtPEX5. Plasmid pAH950 containing ScPEX5 (codons 78–612; ref. 20) and clone #165 were used as templates for PCR mutagenesis. The resulting fragments were cloned into pGBT9 (30) to produce pAH9875. Specific details of cloning procedures are available upon request.

Transformed Strains and Culture Conditions.

Escherichia coli strain HB101 was used for all plasmid isolations and transformations. Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain HF7c (MATa, ura3–52, his 3–200, lys2–801, ade2–101ochre, trp1–901, leu2–3, gal4–542, gal80–538, LYS2∷GAL1-HIS3, URA3∷(GAL4 17-mers)3-CYC1-LacZ) (31) was used in the two-hybrid screen for PTS1 interaction partners. The strain PCY3 (MATα, his3–200, ade2–101ochre, trp1–63, leu2–3, gal4–542, gal80–538, LYS2∷GAL1-HIS3, URA3∷GAL1-lacZ (32) was used for testing the specific interaction of the cDNA clones selected in the initial screen. All yeast transformants were selected and grown at 30°C on the appropriate selective synthetic complete (SC) media supplied with 2% glucose. For fluorescence microscopy, transformed yeast cells were grown at 30°C with shaking (200 rpm) in SC media (0.5% glucose) for 12–16 h, harvested, and resuspended in twice the initial volume of yeast extract/peptone medium with 2% ethanol as the sole carbon source (33). After 8 h of shaking at 30°C the cells were harvested and immediately used for examination under a fluorescence microscope (Leitz). For immunoelectron microscopy experiments, transformed yeast cells were grown with shaking in selective media (SC + 0.5% glucose) for 12–16 h, harvested, and resuspended in twice the initial volume of SC media containing 2.5% ethanol and 0.05% oleic acid without glucose. After 16 h of shaking at 30°C the cells were harvested and processed.

NtPEX5 cDNA Clone Isolation.

The Nicotiana tabacum cDNA library in the pAD-GAL4 phagemid vector used for the two-hybrid screen was a kind gift from Chris Mau (CEPRAP, University of California, Davis). The library plasmids encoded fusion proteins consisting of the Gal4p activation domain and C-terminal amino acid sequence encoded by the cDNA. The bait plasmid, pcoxIV-SKL, expressing a fusion protein consisting of the Gal4-binding domain, subunit IV of cytochrome c-oxidase (coxIV), and a C-terminal PTS1 (-KNIESKL) and the control plasmid, pcoxIV, producing a coxIV fusion protein lacking the C-terminal PTS1 were described previously (20, 34). The two-hybrid screen was conducted as described previously (20, 23). Positive clones were identified as those that conferred histidine auxotrophy and β-galactosidase activity after plasmid isolation and retransformation of strain HF7c. Initial screening of approximately 330,000 transformants yielded about 2,000 histidine auxotrophs. Of these, 400 were tested for β-galactosidase activity, and 5 positives were identified. The library plasmid was isolated from each and used to transform strain HF7c. The specificity of interaction was retested by mating each transformant with strain PCY3 containing either the bait plasmid or the control plasmid. The full-length NtPEX5 clone was obtained in a plaque hybridization screen of the tobacco cDNA library by using the 0.4-kb EcoRI fragment from clone #165 as a probe.

NtPEX5 Function in Yeast.

Clone #165 was used as a template for PCR to obtain a 1.8-kb fragment that was cloned as a PstI fragment into pUC18, resulting in the plasmid LW2. PCR was used to amplify a 0.45-kb fragment harboring the promoter and 37 codons of ScPEX5 (23) that was cloned into Yep352 (35) to produce plasmid LW3. Plasmid LW3 was linearized with PstI and ligated with the 1.8-kb PstI fragment from plasmid LW2. The sequence of the fragment in the resulting plasmid, LW7, verified that it encoded a fusion protein consisting of the first 37 aa of ScPex5p and the C-terminal 553 aa of NtPEX5 under the control of the ScPEX5 promoter. A similar PCR-based cloning strategy was employed to produce plasmid LW8 that encodes 307 aa from the N-terminal half of ScPex5p fused to 274 aa of the NtPEX5 C terminus. Transport into yeast peroxisomes was assessed by localizing the green fluorescent protein from Aequoria victorea extended by the functional C-terminal PTS1, -SKL, described previously (GFP-SKL; refs. 23 and 36). The plasmid YEpScPex5 encoding the wild-type ScPex5p was constructed by ligation of a BamHI-SphI PCR fragment (23) into a BamHI-SphI-digested YEp352 shuttle vector. Immunoelectron microscopy to localize GFP-SKL was done as described previously by using rabbit anti-GFP primary antibody (1:250) and goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (1:200) labeled with 15-nm gold particles (37). Mouse anti-GFP mAb (1:10), rabbit antithiolase polyclonal antibody (1:1,000; gift from W. Kunau, Ruhr-Universität Bochum), 5-nm gold particles coated with goat anti-mouse antibody (1:20), and 10-nm gold particles coated with goat anti-rabbit antibodies (1:20) were used for double-labeling experiments.

β-Galactosidase (β-gal) Activity Measurements.

β-gal filter assays were performed according to the Matchmaker protocol (CLONTECH) after transformants were grown on SC-media plates for 2 days at 30°C. For specific enzyme activity measurements, the yeast cells were grown in liquid media and washed twice with distilled water as described (20). After disruption of the cells at 4°C with glass beads, the protein concentration of the lysate was determined (38) and β-gal activity was measured photometrically at 420 nm by using o-nitrophenyl β-d-galactopyranoside as a substrate (39).

RESULTS

Identification of cDNA Clones Encoding Proteins That Interact with PTS1.

The yeast two-hybrid system (30) was used to identify the tobacco PTS1 receptor. We identified cDNA clones from a suspension culture library encoding proteins that interacted with the PTS1, -SKL, fused to the C terminus of cytochrome oxidase subunit IV (coxIV-SKL). Suspension culture cells have been shown to contain unspecialized peroxisomes that translocate PTS1 proteins (40).

Approximately 330,000 HF7c yeast cells transformed with the pcoxIV-SKL plasmid and plasmids from the tobacco cDNA library were screened initially for histidine auxotrophy (see Materials and Methods). Five cDNA clones consistently conferred both histidine auxotrophy and β-gal activity to transformants, indicating that the encoded proteins interacted with coxIV-SKL, as summarized in Table 1. PTS1-dependent interactions were observed with proteins encoded by three cDNA clones, #114, #165, and #354, whereas the other two cDNA clones, #15 and #351, encoded proteins that interacted with coxIV alone. The three cDNA clones were analyzed further to determine whether they encoded peroxisomal PTS1 receptors.

Table 1.

Interactions between coxIV-SKL and proteins encoded by cDNA clones selected in the two-hybrid screen

| cDNA | BD-coxIV-SKL | BD-coxIV | BD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clone | HIS+ | β-gal | β-gal* | β-gal* |

| #15 | + | +++ | +++ | − |

| #114 | ++ | ++++ | − | − |

| #165 | ++ | ++++ | − | − |

| #351 | ++ | ++++ | ++++ | − |

| #354 | ++ | ++++ | − | − |

The encoding regions of cDNA inserts fused with the Gal4 activation domain were used in the two-hybrid system to test for interactions with the subunit IV of cytochrome c oxidase extended with the C-terminal amino acid sequence-KNIESKL (coxIV-SKL) and coxIV, each of which was fused with the Gal4-binding domain (BD). Transformants were tested for relative growth in the absence of histidine (HIS+) and relative β-gal activity.

β-gal activity was determined in diploid strains derived from the haploid strains PCY3 and HF7 expressing the indicated binding-domain protein and cDNA clone, respectively.

Nucleotide sequencing studies, to be discussed below, showed that clones #114/#165 and #354 represented similar but not identical RNAs, suggesting that they correspond to members of a gene family. RNA gel blot analysis showed that clone #165 hybridized with a 3.1-kb mRNA present in mature seed, seedlings grown for 3 days, and young leaves (data not shown). The cDNA inserts of clones #114, #165, and #354 were 2.0 kb, 2.1 kb, and 1.5 kb, respectively, suggesting that none contained the complete protein coding region. We screened the tobacco suspension culture cDNA library with a fragment from clone #165 and identified several cDNA clones. One clone, P1, had a 2,682-bp cDNA insert and a 2,223-bp ORF with the predicted polypeptide shown in Fig. 1. The insert appeared to contain the complete protein coding region because it had an in-frame translational stop codon upstream of the initiator methionine.

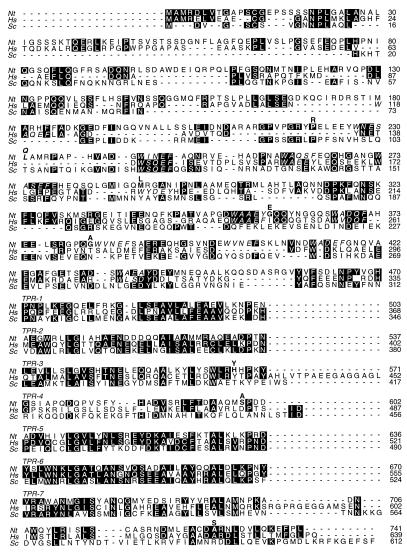

Figure 1.

Amino acid sequence comparison of NtPEX5. The deduced amino acid sequence of NtPEX5 (Nt) is shown in comparison with Pex5ps from humans (Hs) and S. cerevisiae (Sc). The TPR domains were aligned and the N-terminal region of NtPEX5 was compared directly with those of HsPex5p and ScPex5p. Amino acids in bold above the NtPEX5 sequence show differences encoded by clone #165. Italicized residues represent pentapeptide repeats in the tobacco, human, and yeast proteins. Each TPR domain is listed separately; only the first 34 aa residues in each line constitute the TPR. Identical residues in the plant and the human and/or yeast polypeptides are highlighted with a black background. Amino acid residues are numbered to the right.

The deduced amino acid sequence of clone #165 overlapped that of clone P1 from amino acid positions 191–741 (Fig. 1). Although 33 nucleotide sequence differences were detected, these resulted in only eight changes in amino acid sequence. Clone #114 shared identical nucleotide sequences with #165 in their region of overlap. Clone #354 overlapped P1 between positions 410 and 741. By contrast to clone #165, the deduced amino acid sequence of clone #354 was identical with that of P1. Partial nucleotide sequences of six other cDNA clones identified by hybridization showed that they corresponded to either the #165/#114 or the P1/#354 class (data not shown). Together, these results suggest that P1 is a full-length cDNA clone for the putative tobacco PTS1 receptor and that the receptor is encoded by a gene family in tobacco.

The Tobacco PTS1 Receptor Is a Pex5p Homolog.

Sequence analyses and comparisons with the databases using beauty and fasta (41, 42) revealed significant amino acid sequence similarities between the predicted tobacco PTS1 receptor and Pex5p. Similar to all other Pex5ps characterized, the tobacco PTS1 receptor possesses seven TPR domains in the C-terminal region of the protein although the predicted polypeptide was longer than either of its homologs from humans or yeast (Fig. 1). The overall sequence identities of the tobacco PTS1 receptor with human and S. cerevisiae Pex5ps were 29% and 21%, respectively. Within the TPR domains, the extent of sequence identity was higher at 41% and 32%, respectively. Additionally, the tobacco PTS1 receptor contained 10 copies of a pentapeptide repeat, W-[A/L/N/V]-X-[A/E/Q/S]-[F/L/Y] (Fig. 1). Seven and one copy, respectively, of similar repeats were present in the human and S. cerevisiae Pex5ps (Fig. 1). The ability of the tobacco PTS1 receptors to interact with coxIV-SKL and its sequence similarity to HsPex5p and ScPex5p suggested that the tobacco receptor is a Pex5p homolog that we designated NtPEX5, consistent with nomenclature conventions. The data also suggest that NtPEX5 is more similar to its homolog from humans than from yeast.

NtPEX5 Restores Peroxisomal Protein Translocation in a pex5 Yeast Mutant.

To test the function of NtPEX5 as a receptor that mediates the translocation of PTS1 proteins into peroxisomes, we asked whether two fusion proteins containing NtPEX5 sequences could complement the S. cerevisiae pex5 mutation. Plasmid LW7 encoded a fusion protein that consisted of the N-terminal 37 aa of ScPex5p and the 553 C-terminal residues of NtPEX5. Our strategy was to effectively reduce the size of NtPEX5 to that of the yeast homolog while retaining the seven tobacco TPRs in the fusion protein. The second plasmid, LW8, encoded a protein in which the N-terminal 307 aa of ScPex5p was fused with the complete TPR domain of NtPEX5, the C-terminal 274 aa. Each fusion protein gene, under the control of the yeast PEX5 promoter, was expressed in the pex5 mutant yeast strain, CB82, along with a GFP extended by the PTS1 tripeptide, -SKL (GFP-SKL). GFP-SKL was shown previously to be targeted specifically to peroxisomes in wild-type yeast (23, 36).

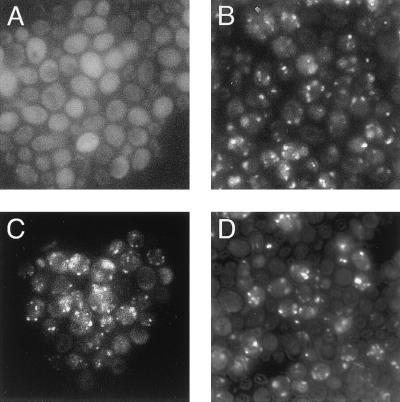

We localized GFP-SKL in a pex5 deletion mutant by using fluorescence and immunoelectron microscopy. In mutant yeast cells transformed with a YEp352 vector with no PEX5 sequences, localization of GFP-SKL was exclusively cytosolic as shown in Fig. 2A. By contrast, GFP-SKL was localized in peroxisomes in mutant cells transformed with a plasmid expressing wild-type ScPex5p, as indicated by the characteristic punctate fluorescence pattern within the cytoplasm (Fig. 2B). As shown in Fig. 2 C and D, pex5 mutant cells expressing either of the NtPEX5 fusion proteins displayed fluorescence patterns similar to that of cells expressing ScPex5p (Fig. 2B), indicating that the TPR domain of NtPEX5 was able to restore the targeting of GFP-SKL to peroxisomes. Cells expressing the NtPEX5 fusion proteins displayed a higher background level of cytosolic GFP-SKL compared with pex5 cells complemented with ScPex5p.

Figure 2.

NtPEX5 restores protein transport to peroxisomes in pex5 mutants. The yeast pex5 mutant strain, CB82, expressing GFP-SKL that is targeted to peroxisomes, was transformed with the following plasmids. GFP-SKL localization was determined by using fluorescence microscopy. (A) Cells transformed with vector only (Yep352) show a diffuse fluorescence pattern because of cytosolic localization of GFP-SKL. (B) Cells expressing the wild-type ScPex5p from YepScPex5 display a punctate fluorescence pattern, showing transport of GFP-SKL to peroxisomes. (C) LW8 transformed cells expressing a ScPex5p-NtPEX5 fusion protein carrying 307 aa from the amino terminus of ScPex5p and 276 aa from the C terminus of NtPEX5. The fluorescence pattern is similar to that observed in B, suggesting NtPEX5-mediated transport of GFP-SKL to peroxisomes. (D) Cells transformed with LW7 expressing a ScPex5p-NtPEX5 fusion protein consisting of 37 N-terminal amino acids of ScPex5p and 553 C-terminal amino acids of NtPEX5. The punctate pattern of GFP-SKL within the cells is similar to that visible in B and C.

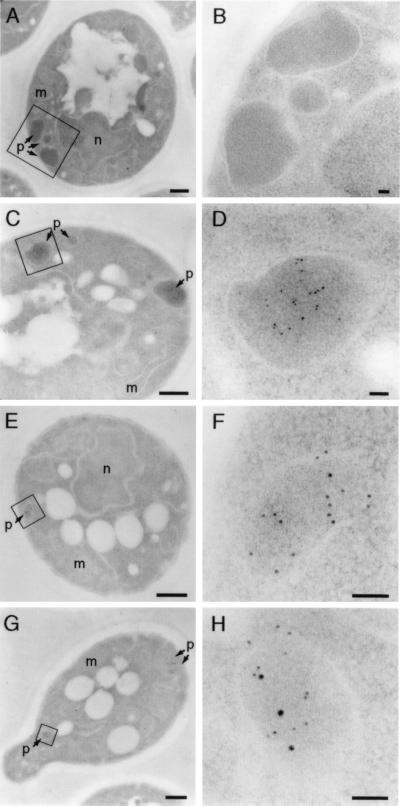

To determine whether the NtPEX5 fusion protein mediated protein translocation into peroxisomes, we localized the reporter protein by using immunoelectron microscopy. Fig. 3 E and F shows that anti-GFP antibodies decorated peroxisomes of pex5 mutant yeast cells expressing GFP-SKL and the ScPex5p (307 residue)–NtPEX5 (274 residue) hybrid protein (LW8), suggesting that the fusion protein restored import into peroxisomes. Control experiments provided additional support for this conclusion. First, GFP-SKL was distributed similarly in pex5 mutants either complemented with ScPex5p (Fig. 3 C and D) or expressing the NtPEX5 fusion protein (Fig. 3 E and F). Second, Fig. 3 G and H shows that peroxisomal thiolase colocalized with GFP-SKL, indicating that the reporter protein was present in peroxisomes. Third, anti-GFP antibodies did not decorate peroxisomes of pex5 mutants expressing ScPex5p but not GFP-SKL, demonstrating its specificity (Figs. 3 A and B). Similar results were obtained by using the other ScPex5p (37 residue)–NtPEX5 (553 residue) fusion protein from LW7. Together, these results strongly suggested that NtPEX5 is the PTS1 receptor and indicated that the TPR domains of the plant and the yeast Pex5p homologs are functionally interchangeable.

Figure 3.

Subcellular localization of GFP-SKL in yeast pex5 mutants expressing a NtPEX5 fusion protein. Anti-GFP antibodies were used to localize GFP-SKL in pex5 mutant strain CB82 by using immunoelectron microscopy. Boxed regions in A, C, E, and G are shown at a higher magnification in B, D, F, and H. (A and B) CB82 cells expressing ScPex5p but not GFP-SKL. Peroxisomes are not labeled. (C and D) Mutant expressing ScPex5p and GFP-SKL. Peroxisomes are decorated specifically. (E and F) pex5 mutants expressing GFP-SKL and the fusion protein consisting of 307 N-terminal amino acids of ScPex5p and 274 C-terminal amino acids of NtPEX5 (LW8). Peroxisomes are specifically labeled. (G and H) Colocalization of thiolase (10-nm gold particles) and GFP-SKL (5-nm gold particles) in mutant cells expressing the ScPex5p-NtPEX5 fusion protein (LW8) and GFP-SKL. m, mitochondrion; n, nucleus; p, peroxisome. [Bars = 400 nm (A, C, E, and G) or 50 nm (B, D, F, and H).]

Interaction of NtPEX5 with PTS1 Variants.

The yeast two-hybrid system was used to define the range of C-terminal peptide sequences that were able to interact with NtPEX5. We analyzed interactions between the protein encoded by plasmid pAH9875 that consisted of the NtPEX5 TRP domain fused with the Gal4p-binding domain and peptides previously shown to interact with HsPex5p and/or ScPex5p (43).

Table 2 shows that NtPEX5 bound to a variety of PTS1 variants with different affinities, as indicated by β-gal activities measured in the two-hybrid assay. The TPR domain of NtPEX5 recognized C-terminal peptides ending in tripeptide sequences previously shown to target proteins to peroxisomes in transgenic plants, [A/C/G/P/S/T]-[H/K/L/N/R]-[I/L/M/Y] (6–8). An exception was that the K01 peptide ending in -SKI did not detectably interact with the TPR domain of NtPEX5 though this tripeptide was shown to be sufficient for targeting chloramphenicol acetyl transferase into plant peroxisomes (6, 7). The experiments also showed that NtPEX5 interacted with peptides Hs50, Hs52, Hs62, and Hs64 ending with -SQL, -SML, -SSL, and -SAL, respectively. These C-terminal tripeptides do not conform with the plant PTS1 consensus sequence. The lack of interaction between NtPEX5 and peptides K02 and K03 that were previously shown not to interact with HsPex5p provided negative controls for the assays (43). Table 2 also shows that the NtPEX5 TPR domain was able to recognize a wide range of peptides previously shown to interact in the two-hybrid assay with HsPex5p, including many that did not interact with ScPex5p (43). We conclude that the plant and human Pex5p homologs share similar binding specificities.

Table 2.

Interactions between PTS1 variants and the TPR domain of NtPEX5

| Peptide | C-terminal amino acid sequence | β-gal activity (SE)* | Interaction with†

|

Tripeptide function in vivo‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Pex5p | Yeast Pex5p | ||||

| Hs04 | −VVYSLLALAVQCSKL | 902 (197) | + | + | + |

| Hs19 | −GETMPPNNIGCTASRL | 441 (20) | + | + | + |

| Hs52 | −SERRLRSML | 534 (40) | + | + | ND |

| Hs35 | −SKVFVSGWGAGGMSRM | 1,244 (80) | + | − | + |

| Hs50 | −SDTIAMNCVQVKSQL | 97 (17) | + | − | ND |

| Hs57 | −PEYSRAGQGTMWRSLL | 1,015 (154) | + | − | ± |

| Hs62 | −DGLWLGNFGVSLCSSL | 302 (32) | + | − | − |

| Hs64 | −AGGRIASNCNLVSAL | 151 (31) | + | − | ND |

| Hs08 | −VGDYKLTVRWAWRAKL | 694 (93) | + | ND | ND |

| Hs27 | −RVCWNGIEQGKKWARL | 389 (20) | + | ND | + |

| Hs31 | −WRIVSPYTGGSLSCKL | 411 (56) | + | ND | + |

| Hs33 | −RDGELVPLYHLIPCRL | 1,068 (299) | + | ND | + |

| Hs36 | −RWLYVWREGWGVRARM | 1,200 (188) | + | ND | ND |

| Hs37 | −IVVVPLTPRCILICRM | 79 (7) | + | ND | ND |

| Hs38 | −ATSQDWAGLPLRSHL | 1,208 (116) | + | ND | + |

| Hs41 | −LYILWGRL | 152 (30) | + | ND | − |

| Hs44 | −RDWEMGMCTGMLWPRL | 1,278 (20) | + | ND | + |

| K01 | −VVYSLLALAVQCSKI | <2 | − | − | + |

| K02 | −VIGMCRLGWLPKGDA | <2 | − | − | ND |

| K03 | −FEWGSQGWTRGRIDML | <2 | − | − | ND |

Interactions were determined by measuring β-gal activity in S. cerevisiae strain PCY3 expressing the TPR domain of NtPEX5 fused with the Gal4p-binding domain from pAH9875 and transformed with plasmids expressing the Gal4-activation domain extended by the indicated peptides. These peptides originally were isolated because of their ability to interact with HsPex5p (43). Control peptides that did not interact with HsPex5p are named K01, K02, and K03 (43). ND, not determined.

Mean of β-gal specific activity (units⋅mg protein−1) measured in the lysate of more than four transformants.

Based on the data of Lametschwandtner et al. (43).

DISCUSSION

cDNAs encoding tobacco proteins that interact with PTS1 were identified by using the two-hybrid assay. The ability of the plant protein to restore PTS1-mediated protein transport in yeast pex5 mutants and sequence comparisons of the deduced NtPEX5 amino acid sequence confirmed that the isolated cDNA encodes a PTS1 receptor from tobacco. The TPR domain of NtPEX5 recognized a range of C-terminal tripeptide sequences in the two-hybrid system that is even broader than the currently established PTS1 consensus for plants.

We have shown that PTS1 receptors are conserved both in primary structure and in function. Pex5ps from plants, humans, and yeast display significant amino acid sequence identity within the TPR domain. Other regions of sequence similarity are also detected outside this domain, particularly in comparisons of the homologs from tobacco and humans (Fig. 1). Our experiments showing that the expression of NtPEX5 fusion proteins in yeast pex5 mutants restores peroxisomal protein translocation suggest that components of the peroxisome transport apparatus are conserved (Figs. 2 and 3). In yeast, Pex5p interacts with the membrane-bound complex of Pex13p and Pex14p during protein translocation into peroxisomes (22–26). Previous studies showed that the N-terminal 77 aa of ScPex5p are not required for its interactions with ScPex14 (23). Therefore, the ability of the fusion protein consisting primarily of NtPEX5 sequences and only 37 N-terminal residues from ScPex5p to reestablish protein transport in pex5 mutants suggests that tobacco NtPEX5 functionally interacts with yeast Pex13p and Pex14p. We also note that the low level of GFP-SKL observed in the cytosol of complemented yeast cells may indicate that the efficiency of protein translocation into peroxisomes is not restored completely by the fusion protein (Fig. 2). The inability of pex5 mutants expressing NtPEX5 fusion proteins to grow when oleic acid is supplied as the sole carbon source provides additional support for this idea (data not shown). Furthermore, pex5 mutants expressing the NtPEX5 fusion protein had fewer peroxisomes compared with those expressing ScPex5p (data not shown).

Our results also indicate that the plant Pex5p is more similar to its homolog from humans than from yeast. NtPEX5 shares greater sequence identity with HsPex5p than with ScPex5p both within and outside the TPR domain (Fig. 1). This relationship also holds when NtPEX5 is compared with homologs from other yeasts including Hansenula polymorpha, Pichia pastoris, and Yarrowia lipolytica (data not shown). Additionally, repeats similar to the consensus sequence W-[A/L/N/V]-X-[A/E/Q/S]-[F/L/Y] are scattered throughout the N-terminal regions of NtPEX5 and HsPex5p, but it is observed only once in the homologs from yeasts (Fig. 1), although the function of these repeats, if any, is not known. Interaction between Pex5p and PTS1 is mediated through the TPR domain (19, 20). Our finding that the TPR domain of NtPEX5 interacts with many PTS1 variants recognized by HsPex5p but not by ScPex5p suggests that the binding specificities of the plant and human Pex5p homologs mirror the sequence identities (Table 2).

The C-terminal tripeptides previously shown to target proteins to plant peroxisomes were recognized by NtPEX5 in the two-hybrid assay with one exception (Table 2). The PTS1, -SKI, that targets a reporter protein to peroxisomes in vivo did not interact with NtPEX5 (peptide K01, Table 2). Additionally, two peptides that did interact with NtPEX5, Hs62 and Hs41 ending in -SSL and -GRL, respectively, previously were shown not to target a reporter protein to peroxisomes (6). These differences may reflect the influence of accessory amino acid residues preceding the PTS1. Mullen et al. (7) suggested that these neighboring amino acids may enhance the ability of “weak” PTS1s to serve as targeting determinants. Peptide Hs04 that interacts strongly with NtPEX5 and peptide K01 that does not interact differ only by the C-terminal amino acid. This result suggests that the “strong” PTS1, -SKL, can be recognized by NtPEX5 without auxiliary upstream residues. Other peptides ending in -SQL, -SML, -SSL, and -SAL that interacted with NtPEX5 also deviated from the suggested plant PTS1 consensus [A/C/G/P/S/T]-[H/K/L/N/R]-[I/L/M/Y] (6–8). Future studies will show whether these tripeptides are sufficient to target heterologous proteins to peroxisomes in plants.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Wabnegger and K. Mastudaira Yee for technical assistance, M. Binder for help with the immunoelectron microscopy, K. C. McFarland of the National Science Foundation Plant Cell Biology Training Facility at University of California, Davis, for help with the figures, and W. Kunau for antibodies. This work was supported by the Austrian FWF Grant 10725-MOB to A.H. and by a National Science Foundation grant to J.J.H. F.K. was supported by an Erwin Schrödinger Fellowship (J1249-GEN) provided by the Austrian FWF, and J.C. was supported, in part, by a National Science Foundation-Research Opportunity Awards supplement to J.J.H.

ABBREVIATIONS

- GFP-SKL

green fluorescent protein with the C-terminal PTS1 extension, -SKL

- PTS1 and PTS2

C-terminal and N-terminal peroxisomal targeting signal, respectively

- Pex5p

peroxisomal import receptor for PTS1-containing proteins

- TPR

tetratricopeptide repeats

- β-gal

β-galactosidase

Footnotes

References

- 1. Huang A H C, Trelease R N, Moore T S., Jr . Plant Peroxisomes. New York: Academic; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsen L J, Harada J J. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1995;46:123–146. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rachubinski R A, Subramani S. Cell. 1995;83:525–528. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Subramani S. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:445–478. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.002305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gould S J, Keller G A, Subramani S. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:2923–2931. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.6.2923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayashi M, Aoki M, Kondo M, Nishimura M. Plant Cell Physiol. 1997;38:759–768. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mullen R T, Lee M S, Trelease R N. Plant J. 1997;12:313–322. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1997.12020313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mullen R T, Lee M S, Flynn C R, Trelease R N. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:881–889. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.3.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gietl C, Faber K N, Van Der Klei I J, Veenhuis M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3151–3155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kato A, Hayashi M, Kondo M, Nishimura M. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1601–1611. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.9.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kato A, Hayashi M, Takeuchi Y, Nishimura M. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;31:843–852. doi: 10.1007/BF00019471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trelease R N, Choe S M, Jacobs B L. Eur J Cell Biol. 1994;65:269–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onyeocha I, Behari R, Hill D, Baker A. Plant Mol Biol. 1993;22:385–396. doi: 10.1007/BF00015970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olsen L J, Ettinger W F, Damsz B, Matsudaira K, Webb M A, Harada J J. Plant Cell. 1993;5:941–952. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.8.941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishimura M, Yamaguchi J, Mori H, Akazawa T, Yokota S. Plant Physiol. 1986;80:313–316. doi: 10.1104/pp.81.1.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Titus D E, Becker W M. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:1288–1299. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.4.1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Distel B, Erdmann R, Gould S J, Blobel G, Crane D I, Cregg J M, Dodt G, Fujiki Y, Goodman J M, Just W W, et al. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1–3. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subramani S. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32483–32486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fransen M, Brees C, Baumgart E, Vanhooren J C, Baes M, Mannaerts G P, Van Veldhoven P P. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7731–7736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brocard C, Kragler F, Simon M M, Schuster T, Hartig A. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;204:1016–1022. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lamb J R, Tugendreich S, Hieter P. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:257–259. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Albertini M, Rehling P, Erdmann R, Girzalsky W, Kiel J A, Veenhuis M, Kunau W H. Cell. 1997;89:83–92. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80185-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brocard C, Lametschwandtner G, Koudelka R, Hartig A. EMBO J. 1997;16:5491–5500. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.18.5491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gould S J, Kalish J E, Morrell J C, Bjorkman J, Urquhart A J, Crane D I. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:85–95. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erdmann R, Blobel G. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:111–121. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elgersma Y, Kwast L, Klein A, Voorn-Brouwer T, Van Den Berg M, Metzig B, America T, Tabak H F, Distel B. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:97–109. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brickner D G, Harada J J, Olsen L J. Plant Physiol. 1997;113:1213–1221. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.4.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolins N E, Donaldson R P. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1149–1153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fields S, Song O. Nature (London) 1989;340:245–246. doi: 10.1038/340245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feilotter H E, Hannon G J, Rudell C J, Beach D. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1502–1503. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.8.1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chevray P M, Nathans D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5789–5793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.5789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. New York: Wiley; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kragler F, Langeder A, Raupachova J, Binder M, Hartig A. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:665–673. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.3.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hill J E, Myers A M, Koerner T J, Tzagaloff A. Yeast. 1986;2:163–167. doi: 10.1002/yea.320020304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Monosov E Z, Wenzel T J, Luers G H, Heyman J A, Subramani S. J Histochem Cytochem. 1996;44:581–589. doi: 10.1177/44.6.8666743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Binder M, Hartig A, Sata T. Histochem Cell Biol. 1996;106:115–130. doi: 10.1007/BF02473206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bradford M M. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller H J. Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trelease R N, Lee M S, Banjoko A, Bunkelmann J. Protoplasma. 1996;195:156–167. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pearson W R. Protein Sci. 1995;4:1145–1160. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Worley K C, Wiese B A, Smith R F. Genome Res. 1995;5:173–184. doi: 10.1101/gr.5.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lametschwandtner, G., Brocard, C., Fransen, M., Van Veldhoven, P., Berger, J. & Hartig, A. (1998) J. Biol. Chem., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]