Abstract

Long-range promoter–enhancer interactions are a crucial regulatory feature of many eukaryotic genes yet little is known about the mechanisms involved. Using cloned chicken βA-globin genes, either individually or within the natural chromosomal locus, enhancer-dependent transcription is achieved in vitro at a distance of 2 kb with developmentally staged erythroid extracts. This occurs by promoter derepression and is critically dependent upon DNA topology. In the presence of the enhancer, genes must exist in a supercoiled conformation to be actively transcribed, whereas relaxed or linear templates are inactive. Distal protein–protein interactions in vitro may be favored on supercoiled DNA because of topological constraints. In this system, enhancers act primarily to increase the probability of rapid and efficient transcription complex formation and initiation. Repressor and activator proteins binding within the promoter, including erythroid-specific GATA-1, mediate this process.

Keywords: β-globin gene, in vitro transcription, DNA topology, GATA-1, derepression, enhancers

The regulation of promoters by distal enhancers within complex genetic loci has been the subject of intense investigation. Models of communication between distant protein–DNA complexes include DNA looping, protein tracking, or changes in DNA topology, each of which is thought to activate transcription by increasing the local concentration of factors in the vicinity of the promoter (1–5). It has been difficult to directly test these models or elucidate other mechanistic information regarding long-range communication experimentally. Thus, the ability to recreate distal transcriptional regulation in vitro would provide a valuable biochemical tool to investigate how enhancers or other genetic elements acting at a distance actually function.

Previous in vitro analyses of enhancer control generally relied on placing these elements within 400 bp or less of the start site of transcription with enhancer activity diminishing over longer distances from the promoter (2). Distal activation has been reported on model DNA templates by derivatives of strong activators, such as GAL4–VP16 (6), and on natural yeast ribosomal RNA genes in cell-free extracts (7). Another study demonstrated that long-range transcriptional regulation by GAL4-VP16 is dependent on histone H1-containing chromatin, indicating that a precise nucleosome configuration is necessary to mediate this effect (8). These studies support models in which distal enhancers regulate transcription by direct activation of an initiation complex or by displacement of chromatin components, using the potent activator GAL4–VP16.

We have previously reported enhancer-dependent transcription of the chicken βA-globin gene within cosmids containing its 40-kb chromosomal locus when assembled into chromatin and synthetic nuclei by Xenopus egg extracts in the presence of stage-specific erythroid proteins (9). We wished to exploit this in vitro system to define the minimum structural requirements needed for long-range enhancer regulation of natural RNA polymerase II-transcribed genes. As a first step, conditions were devised in which cloned βA-globin templates were transcribed in an enhancer-dependent manner in soluble, nuclear protein extracts prepared from 11-day, definitive, chicken embryo red blood cells (RBC) that normally express the endogenous adult β-globin gene. Somewhat surprisingly, the Xenopus nucleosome assembly extract was completely dispensable for this process; neither extensive chromatin formation nor nuclear membrane attachment was required to generate distal promoter-enhancer interactions. Enhancer-regulated gene expression was observed using either plasmids containing the 4.2-kb βA-globin gene flanked by its promoter and 3′ β-ɛ enhancer or cosmids encompassing the entire 40-kb β-type globin locus. In both templates the β-ɛ enhancer was in its natural location at a distance of 2 kb 3′ of the βA-globin promoter. We have employed this enhancer-dependent in vitro transcription system to define the essential role of DNA topology in mediating regulation through specific enhancer-responsive regions of the promoter. Our results demonstrate that distal enhancer elements derepress the inactive βA-globin gene promoter in the presence of specific erythroid proteins and confer an increased probability of productive transcription complex formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid Constructions.

Cosmids containing the entire 38-kb chicken β-type globin gene locus sCos5βA1 and a derivative deleted of the shared βA- and ɛ-enhancer sCos5βA1/Δenh have been described previously (10). Plasmids containing the isolated 4.2-kb βA-globin gene pUC18ABC/Δ1, a derivative deleted of the β-ɛ enhancer pUC18AB/ΔC, and constructs with 5′ end deletions or point mutations within the promoter have also been described (11, 12).

Preparation of DNA Templates.

Except where noted in the text, all plasmids employed in these studies were negatively supercoiled preparations of DNA that were isolated from bacterial cultures by standard alkaline lysis/CsCl purification methods (13). Relaxed DNA templates were prepared by incubation with Wheat Germ DNA topoisomerase I (General Mills, Vallego, CA) according to the method of Dynan et al. (14). Restriction enzyme-digested DNAs were processed and purified by standard methods (13).

Preparation of Protein Extracts and in Vitro Transcription.

In vitro transcription extracts were prepared from primary chicken erythrocytes at 11 days of embryonic development (11). Cells were collected, washed twice with cold PBS, gently resuspended in hypotonic buffer (10 mM Hepes, pH 7.9/10 mM NaCl/3 mM MgCl2/1 mM DTT/0.3 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride), and incubated for 10 min on ice. Cells were immediately pelleted, resuspended in 2× packed cell volume of hypotonic buffer containing 15% glycerol, and lysed by Dounce homogenization with 15 strokes of a B pestle. Nuclei were pelleted, resuspended in hypotonic buffer plus 15% glycerol, and extracted by the addition of ammonium sulfate to a final concentration of 0.4 M for 30 min at 4°C with stirring in the presence of protease inhibitors (3 μg/ml pepstatin/0.5 μg/ml leupeptin/2 μg/ml aprotinin/1 μg/ml benzamidine/0.3 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). Nuclei were centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, and proteins were precipitated by the addition of solid ammonium sulfate to 0.35 g/ml if further concentration was necessary. Protein extracts were dialyzed for 6 hr at 4°C in RBC buffer (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.9/50 mM KCl/0.2 mM EDTA/1 mM DTT/0.3 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 20% glycerol) and briefly centrifuged to remove insoluble debris. Small volume aliquots were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −100°C. For some experiments, this extract (designated RBC*) was modified by washing the nuclei two to three times after Dounce homogenization, which removes some nuclear proteins. Control HeLa extracts were prepared in an identical manner as the corresponding RBC extract. The total protein concentration of each extract was 15–20 mg/ml. Recombinant mGATA-1 (pETmGATA-1) was expressed and purified as described (15). In vitro transcription reactions utilizing 0.5 μg of plasmid DNA in a final volume of 50 μl were performed and analyzed by S1 nuclease digestion under the conditions previously described (11). The autoradiograms in Figs. 2, 3, 4 were scanned with a Hewlett–Packard ScanJet IIcx/T, and the images were processed in canvas 3.5.1.

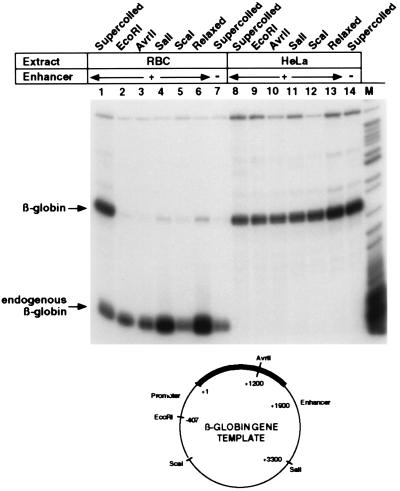

Figure 2.

Enhancer-dependent βA-globin transcription requires a supercoiled DNA topology. In vitro transcription of βA-globin topological isomers: DNA templates described below and within the text were transcribed with extracts from 11-day RBCs (lanes 2–6) or HeLa cells (lanes 9–13). Transcription of supercoiled βA-globin genes containing the β-ɛ enhancer (lanes 1 and 8) or deleted of this region (lanes 7 and 14) was also performed in these extracts. Diagram of restriction cleavages used to generate βA-globin gene templates: A negatively supercoiled preparation of the βA-globin gene plasmid containing the 3′ β-ɛ enhancer was relaxed by incubation with topoisomerase I or digested with individual restriction enzymes that each cut at a unique site: EcoRI, 5′ of the promoter (−407); Avr II, within the coding region at +1202; SalI, 3′ of the enhancer; and ScaI, within the vector.

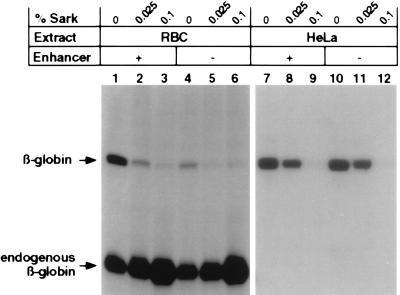

Figure 3.

Enhancer commitment is concomitant with transcription initiation. In vitro transcription of a supercoiled preparation of the βA-globin gene plasmid (0.5 μg) was performed as described under conditions that permit multiple rounds of transcription (0.0% Sarkosyl; lanes 1, 4, 7, and 10), a single round of transcription (0.025% Sarkosyl; lanes 2, 5, 8, and 11) or inhibit elongation (0.10% Sarkosyl; lanes 3, 6, 9, and 12). No enhancer-dependent transcription is observed in the HeLa transcription extract under the identical conditions of transcription (lanes 7–12).

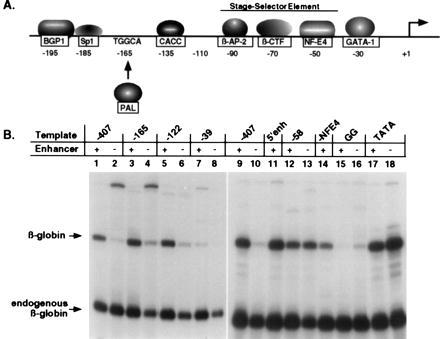

Figure 4.

Enhancer activity is dependent upon specific regions of the βA-globin promoter from −120 through the −30 GATA site. (A), Diagram of trans-acting proteins that bind the chicken βA-globin gene promoter. (B), Transcription of mutated chicken βA-globin gene plasmids. DNA templates containing sequential 5′ deletions of the promoter from −407 to −39 and site-specific mutations at −30 were analyzed for enhancer-regulated transcription by incubation with 11-day RBC extracts (refs. 11 and 12). The reactions shown in lanes 1–8 and lanes 9–18 were obtained from separate experiments. Templates with 5′ sequential truncations containing (+) or deleted (−) of the 3′ β-ɛ enhancer are as follows: full-length promoter to −407 (lanes 1 and 2; 9 and 10); −165 (lanes 3 and 4); −122 (lanes 5 and 6); −39 (lanes 7 and 8); −58 (lanes 12 and 13). Templates containing site-specific mutations are as follows: −NF-E4 (lane 14); −30 GAGG ± enhancer (lanes 15 and 16); −30 TATA ± enhancer (lanes 17 and 18). Other βA-globin templates contain the β-ɛ enhancer moved 5′ of the promoter (5′ enh: lane 11).

Conditions for in vitro transcription in the presence of N-lauroylsarcosine (Sarkosyl; Sigma) were basically as described by Hawley and Roeder (16, 17). Preinitiation complexes were allowed to form for 10 min at 30°C in the absence of NTPs. Sarkosyl detergent and NTPs were added simultaneously, and transcription proceeded for 1 hr at 30°C. To limit transcription to a single round, 0.025% Sarkosyl was added. Inhibition of transcription elongation occurred upon the addition of 0.1% Sarkosyl. Excising and counting the labeled S1-protected βA-globin RNA from the 8 M urea/polyacrylamide gel allowed the quantitation of transcripts produced under each reaction condition. The percentage of templates transcribed was determined under single-round transcription conditions, as described above, and by calculation of percent template usage during multiple rounds of transcription divided by the total number of rounds.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Distal Enhancers Regulate Transcription by Derepression of Promoter Activity.

In vivo studies have shown that the shared β-ɛ enhancer is positioned between the adult β-globin and embryonic ɛ-globin genes and regulates each promoter at different times in erythroid development (18, 19). Although β-ɛ enhancer activation is conferred mainly by the interaction of two erythroid-restricted proteins, GATA-1 and NF-E2, within an intergenic region of 126 bp (20), βA-globin promoter selection by the enhancer in definitive red cells is dependent upon the binding of several stage-specific transcription factors to the proximal promoter (21). We have reproduced an in vitro transcription system that displays an absolute dependence on the presence of the distal enhancer by transcription of chicken βA-globin DNA templates in crude nuclear extracts of developmentally staged erythroid cells.

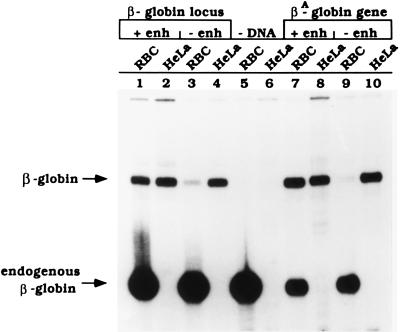

In vitro transcriptional analysis of chicken βA-globin plasmid and cosmid templates in 11-day RBC extracts resulted in efficient gene expression only in the presence of the 3′ distal β-ɛ enhancer (Fig. 1, compare lanes 1 and 3 with 7 and 9). By contrast, these templates were transcribed with equal efficiency under the same conditions in HeLa extracts in the presence or absence of the 3′ enhancer (compare lanes 2 and 4, with 8 and 10). HeLa extracts are an enriched source of general transcription factors, and they efficiently transcribe most genes in vitro with no tissue-specificity. We have used these extracts as a control to demonstrate that each of our DNA templates are active under deregulated conditions. These results indicate that: i, in the absence of the β-ɛ enhancer, the βA-globin promoter is active in HeLa extracts but is inactivated by proteins present in erythroid extracts; ii, promoter repression in erythroid extracts is relieved by the distal enhancer; and, iii, the maximal levels of βA-globin transcription are the same in the two extracts. The degree of distal enhancer function in this in vitro system is determined by repression of promoter activity in the absence of the enhancer in RBC extracts. Quantitative analyses reveal an average 58-fold derepression of β-globin gene transcription due to enhancer function in RBC extracts. This level of in vitro enhancer activity compares well with experiments in which the β-ɛ enhancer was placed 3′ of a CAT reporter gene driven by the βA-globin promoter and transiently transfected into chicken primary erythrocytes (80-fold activation; ref. 22).

Figure 1.

The 3′ β-ɛ enhancer is required for βA-globin gene transcription in vitro. Transcription of chicken β-globin locus cosmids and βA-globin gene plasmids in erythroid and HeLa cell extracts in the presence or absence of the β-ɛ enhancer. DNA templates consisted of the following: the chicken β-globin locus in its entirety (lanes 1 and 2) or with the shared enhancer of the βA- and ɛ- globin genes (E) deleted (lanes 3 and 4); the individual βA-globin gene with the complete β-ɛ enhancer in its natural 3′ location (lanes 7 and 8) or with the enhancer deleted (lanes 9 and 10); and no DNA (lanes 5 and 6). These templates were transcribed in vitro using extracts prepared from 11-day chicken embryonic RBC (odd-numbered lanes; RBC) or HeLa fibroblast cells (even-numbered lanes; HeLa) and analyzed by S1 nuclease digestion as described (11). In vitro-generated β-globin RNA and the β-globin message endogenous to the erythroid extract are designated by arrows. Derepression of transcription activity by RBC extracts is 58.7-fold for isolated βA-globin gene plasmids (data averaged from nine experiments), and 6.8-fold for β-globin locus cosmids (data from five experiments) in a comparison of enhancer-plus and enhancer-minus transcription reactions.

Within the β-globin locus cosmid clone are the previously described 5′ hypersensitive sites (more than 10 kb 5′ of the βA-globin promoter) characteristic of the locus control region in the human β-globin gene family (23, 24). Although deletion of the β-ɛ enhancer from the β-globin locus cosmid greatly decreased transcription in the RBC extracts, a low level of βA-globin RNA transcripts is produced (Fig. 1, lane 3), and complete repression was not achieved (compare lane 3 with lane 9). The remaining cis-acting elements including the 10 kb distal 5′ locus control region within the cosmid clone contributed approximately 7-fold to overall enhancer activity in this system (compare lane 1 with lane 3). Thus, this in vitro system reproduces critical aspects of β-ɛ enhancer and possible locus control region enhancer activity in the context of the chromosomal locus or individual gene.

A Supercoiled DNA Structure Is Essential for Enhancer Function.

With the availability of an enhancer-dependent in vitro transcription system, we have determined an absolute requirement for specific DNA template topology in the regulation of promoter activity by distal enhancers. βA-Globin gene expression in erythroid extracts is silenced as efficiently by disrupting the supercoiled structure of the enhancer-containing DNA template as by deleting the entire enhancer element (Fig. 2). This was demonstrated either by linearizing supercoiled βA-globin gene plasmids with restriction enzymes or by forming relaxed DNA topoisomers and comparing the transcriptional activity of each to supercoiled control templates by incubation in both enhancer-dependent erythroid extracts (lanes 1–7) and enhancer-independent HeLa extracts (lanes 8–14).

Digestion of βA-globin gene plasmids with a uniquely cutting enzyme either midway between the promoter and enhancer within both the gene coding region (Avr II, Fig. 2, lane 3) and the plasmid vector sequences (ScaI, lane 5), 5′ distal of the promoter (EcoRI, lane 2) or 3′ distal of the enhancer (SalI, lane 4) severely diminished βA-globin transcription (compare with lane 1). Quantifying these results revealed an average 2-fold derepression of linear templates in the presence of the enhancer (lanes 2–5 versus lane 7), as compared with an approximately 60-fold derepression of supercoiled templates (lane 1 compared with lane 7, and in Fig. 1) in RBC extracts. Incubation of βA-globin gene plasmids with topoisomerase I to convert supercoiled DNA to a mixture of predominantly relaxed, isomeric topological forms also disrupted enhancer-mediated derepression, resulting in 3.2-fold derepressed transcription activity (Fig. 2, lane 6 versus lane 7). Conversely, relaxation of enhancer-deleted templates resulted in a 2-fold induction of promoter-driven transcription in RBC extracts (data not shown). As an essential control, each DNA template was transcribed with relatively equal efficiency when assayed in a HeLa extract, indicating that βA-globin expression by general initiation factors and ubiquitous activators present in these extracts is independent of DNA topology in the presence or absence of the enhancer (lanes 8–14). Although these crude transcription extracts rapidly relax supercoiled plasmids, protein complex assembly on input DNA is very rapid in these reactions. Our results are consistent with the view that DNA topology influences the type of structure that is immediately assembled on the template. This structure must be stable during the transcription reaction, even in the presence of topoisomerases, because supercoiled enhancerless β-globin genes remain repressed and enhancer-containing genes remain active in RBC extracts throughout the incubation period. The topological form and structure of the DNA that is actively transcribed or repressed is currently under investigation.

Distal Enhancers Act by Increasing the Probability of Transcriptional Activation.

To determine whether enhancers function by promoting multiple rounds of transcription or by increasing the relative number of derepressed promoters, we analyzed in vitro expression of supercoiled βA-globin gene plasmids in the presence of varying concentrations of Sarkosyl detergent to limit the number of rounds of transcription per template (16, 17). As shown in Fig. 3, multiple rounds of transcription occur in the absence of detergent (lanes 1, 4, 7 and 10). However, reinitiation is inhibited by the addition of 0.025% Sarkosyl after preinitiation complex formation (lanes 2, 5, 8, and 11) and the addition of 0.1% Sarkosyl disrupts transcription completely (lanes 3, 6, 9, and 12).

Quantitation of transcription in RBC extracts revealed that 11.2% of total DNA templates were transcribed in the presence of the enhancer, versus a 1.3% usage in the absence of the enhancer. By restricting transcription to a single round (0.025% Sarkosyl added, lanes 2 and 5) and comparing it to reactions performed in the absence of detergent (lanes 1 and 4), we determined that 11 rounds of transcription occur in the presence of the enhancer and six rounds in the absence, only a 1.8-fold difference. No differences in template usage or rounds of transcription initiation as a result of enhancer deletion were observed with the HeLa transcription reactions (lanes 7–12). Therefore, topologically constrained enhancer–promoter interaction promotes a higher probability of preinitiation complex formation on a greater number of DNA templates in an erythroid-specific, enhancer-dependent in vitro transcription system. This results in the control of gene expression primarily at the level of initiation rather than by inducing multiple rounds of transcription via an enhancer-modified polymerase complex.

Specific Regions of the Promoter Are Required for Enhancer Control of Transcription.

The chicken βA-globin promoter is regulated by a complex array of tissue- and developmental stage-specific proteins in combination with general transcription factors (see Fig. 4A and refs. 11, 24–29). We examined βA-globin genes containing progressive 5′ deletions or site-specific mutations within the promoter by in vitro transcription using RBC extracts. The results of these studies established which factor binding sites are required for enhancer-dependent expression and identified tissue-specific factors that are critical for this level of gene regulation.

In agreement with previous transfection analyses (22), the β-ɛ enhancer can regulate βA-globin transcription whether it is located 2 kb 3′ of the gene or in reverse orientation 1 kb 5′ upstream of the +1 site (Fig. 4B, lane 11; 95% enhancer function). βA-globin promoters deleted to −165 (lanes 3 and 4; 93% enhancer function) or −122 (lanes 5 and 6; 94% enhancer function) were still regulated by the distal β-ɛ enhancer nearly as effectively as the full-length promoter to −407 (lanes 1, 2, 9, and 10; 100% enhancer function). Promoters truncated to −122 interact with at least four erythroid proteins (β-AP2, β-CTF, and NF-E4), which are stage-specific and present in highest concentrations in definitive red cells and GATA-1 which is present throughout red cell development. The proteins β-AP2, β-CTF, and NF-E4 bind the chicken βA-globin developmental stage-selector element and mediate the developmental switch from ɛ-globin to βA-globin expression in vivo (21).

Further deletion beyond −122 to −58 within the stage-selector element, which removes the binding sites for β-AP2 and β-CTF, greatly diminished enhancer-dependent transcription (Fig. 4B, lanes 12 and 13; 24% of enhancer function) compared with the full-length promoter (lanes 9 and 10; 100% of enhancer function). This indicates that one or both of these developmental factors is critical for the selective repression of βA-globin promoters, which is specifically relieved by the distal enhancer. NF-E4 is an efficient activator of βA-globin promoter-driven transcription (30% reduction in transcription activity due to site-specific mutation, lane 14). However, in the absence of other trans-acting factors, NF-E4 does not support enhancer control of expression resulting in a high basal promoter activity in the absence of the enhancer (lanes 12 and 13). Deletion of the promoter to −39, leaving only GATA-1 bound at the −30 site, was sufficient for low levels of promoter function (lane 7) that proved to be enhancer-dependent (lane 7 versus 8, 129% of enhancer function). Thus, by eliminating the additive effects of multiple factors binding between −407 to −122 and NF-E4, the critical mediators of enhancer-promoter communication are identified as β-AP2, β-CTF, and GATA-1. This is in agreement with previous demonstrations of β-ɛ enhancer-controlled globin gene switching in cell culture (21).

A Noncanonical TATA Box Mediates Enhancer Regulation of βA-Globin Gene Expression.

Site-specific mutations at the −30 GATA initiation sequence show an absolute dependence of enhancer regulation on the binding of the GATA-1 protein. Mutation of this site to a canonical TATA box, which binds TBP/TFIIID but eliminates GATA-1 interaction (12), preserves promoter function (Fig. 4B, lane 17) but completely abolishes enhancer-dependent transcription (lane 18). It is postulated that GATA-1 must first bind at −30 to recruit the enhancer and then be displaced by TBP/TFIID, in combination with TFIIA-like cofactors, to initiate transcription (12). The loss of this specific order of events by mutation to a canonical TATA sequence underscores the possible role of kinetics in enhancer-directed expression. Another mutation at the −30 GATA site (GAGG) completely eliminated both promoter function, presumably due to the lack of TBP/TFIID binding, and enhancer-dependent transcription, due to the lack of GATA-1 binding (Fig. 4B, lanes 15 and 16; 1% of control enhancer function). Thus, GATA-1 must be bound to both the enhancer and the −30 initiation site within the promoter for distal enhancer regulation to occur in vitro. These results emphasize the importance of GATA-1 protein in the context of both promoter and enhancer control of transcription.

Trans-Acting Erythroid Factors Can Complement an Enhancer-Deficient Transcription Extract and Confer Enhancer-Dependent Regulation.

Our analyses indicate that promoter derepression is a critical feature of long-range regulation because 5′ deletions or mutations that abrogate enhancer dependence result in equivalent or greater levels of gene expression in the presence or absence of the enhancer (e.g, see Fig. 4B, −58; lanes 12 and 13, and TATA; lanes 17 and 18). These results suggest that repressor proteins may interact directly or indirectly with enhancer-responsive regions of the promoter, such as −30 GATA and the stage-selector element, and be relieved by the action of the distal 3′ β-ɛ enhancer. In addition, enhancers may replicate promoters by activation as well as by derepression in view of the complex balance of positive and negative factors that control the net activity of the gene. Identification of cis-acting elements, and the proteins that interact with them, that are involved in enhancer regulation of promoter activity suggests the following: (i) the addition of enhancer-dependent erythroid extracts to enhancer-independent HeLa extracts should confer long-range regulation of βA-globin promoter activity, and (ii) the depletion of factors that bind to critical cis-acting elements from enhancer-dependent RBC extracts may result in a loss of enhancer-mediated transcription.

In support of these predictions, complementation of HeLa extracts with limited concentrations of RBC extracts efficiently restores enhancer-dependent βA-globin expression, as shown in Fig. 5. This is achieved by the erythroid-specific repression of βA-globin genes that lack the enhancer (lanes 7–9) and the derepression of templates linked to the enhancer (lanes 2–4). Interestingly, the addition of RBC proteins to HeLa extracts does not amplify the overall level of βA-globin transcription or nonspecifically repress promoters in the presence of the enhancer (lanes 1–4), rather it selectively inactivates transcription only in the absence of the enhancer (lanes 7–9). These results underscore the interpretation that enhancer-dependent transcription is the result of derepression of promoter activity rather than amplification of basal expression.

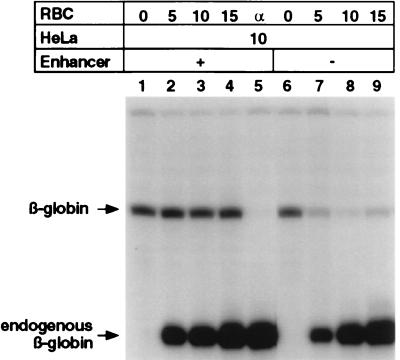

Figure 5.

The β-ɛ enhancer regulates βA-globin transcription by promoter derepression. In vitro transcription of βA-globin gene plasmids in HeLa extracts complemented with enhancer-dependent RBC extracts was performed as described above by addition of 10 μl of HeLa extract to 0.5 μg of βA-globin plasmid DNA in each reaction (lanes 1–9). RBC extracts were added simultaneously with HeLa extracts in the indicated amounts to βA-globin genes containing (lanes 1–5) or deleted (lanes 6–9) of the enhancer. Reaction volumes were held constant by addition of nuclear extract dialysis buffer. Transcription was dependent on RNA polymerase II as indicated by sensitivity to α-amanitin (lane 5).

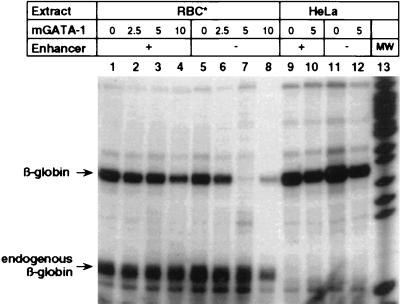

Depletion of GATA-1 Protein Results in a Loss of Enhancer Control of Transcription.

Our results and those of others indicate that multiple proteins binding to the promoter (GATA-1, β-AP2, β-CTF) and enhancer (GATA-1, NF-E2) are critical for enhancer-dependent βA-globin expression. A transcription analysis shown in Fig. 6 demonstrates that the depletion of one essential protein, GATA-1, from enhancer-responsive RBC extracts (generating RBC* extracts, see Materials and Methods) results in a loss of enhancer regulation (lanes 1 and 5). Enhancer-dependent transcription can be restored to GATA-1-depleted RBC* extracts by the addition of recombinant mGATA-1 functioning in combination with β-AP2, β-CTF, and other retained erythroid transcription factors (compare lanes 2–4 with lanes 6–8 in Fig. 6). By contrast, the addition of mGATA-1 to HeLa extracts in the absence of additional erythroid factors failed to confer enhancer-dependent control of βA-globin transcription (Fig. 6, lanes 10 and 12), although complementation with crude RBC extract did result in enhancer-regulated expression (Fig. 5).

Figure 6.

Depletion of GATA-1 protein from RBC extracts abrogates enhancer regulation of βA-globin expression. In vitro complementation analysis using enhancer-independent RBC* and HeLa extracts in combination with mGATA-1. βA-Globin gene plasmids, either enhancer-plus (lanes 1–4, 9 and 10) or enhancer-minus (lanes 5–8, 11 and 12), were incubated with the following concentrations of purified, recombinant mGATA-1 prior to transcription with either 11-day RBC* (lanes 1–8) or HeLa extracts (lanes 9–12) that do not support enhancer-regulated expression: 2.5, 5, and 10 footprinting units in lanes 2–4 and 6–8, respectively; and 5 footprinting units in lanes 10 and 12.

The likely interaction of GATA-1 with other critical erythroid factors present in the RBC* extracts during enhancer-mediated derepression of promoter activity is further supported by the reduced or “squelched” enhancer-dependent transcription in the presence of a high concentration of the recombinant mGATA-1 protein (Fig. 6, lanes 4 and 8). These high concentrations of GATA-1 may deplete cofactors and result in both a lower overall transcription level (lane 4) and an aberrant derepression of the enhancerless template (lane 8). GATA-1 and other erythroid proteins that are required for enhancer-regulation may stabilize a torsionally constrained DNA structure that we have shown to be essential for this type of control. Identification of these cofactors and their mechanism of action are the subject of a current investigation.

Mechanisms of Enhancer-Regulated Gene Expression.

We have shown that two major criteria must be met for enhancer-dependent transcription in vitro to occur. First, our data support the idea that long-range regulatory interactions are more complex than simply involving protein–protein interaction through space or protein translocation along contiguous DNA without a significant contribution from DNA conformation. Enhancer control of transcription displays a critical dependence on DNA topology that may affect the spatial proximity of distal sequences, as proposed previously (2), and the potential to form non-B DNA structures. Destruction of the supercoiled conformation by relaxing or linearizing the enhancer-containing DNA templates effectively abolishes transcription. Second, the binding of trans-acting factors either directly to the promoter or by protein–protein interactions results in transcription repression in the absence of the enhancer. Relief of repression could be accomplished by physical displacement of repressors or altered protein–protein interactions due to enhancer communication with the promoter.

Enhancer-mediated derepression of transcription results in an increased probability of initiation and relies on the interaction of specific erythroid factors within the promoter and enhancer regions. Our in vitro findings support the “binary model” of enhancer function in which apparent activation of gene expression in vivo occurs by derepression of a given gene in an increased number of actively expressing cells rather than by an enhanced rate or level of transcription (30–32). We favor the view that DNA topology strongly influences transcription by immediately promoting the assembly of specialized structures that are required for enhancers to exert their regulatory effects. Indeed, DNA supercoiling may greatly increase the probability of forming direct protein–protein interactions between distal sites (2, 33). Although enhancer function may not be required continuously, the structures involved in promoter repression are apparently very stable in the absence of enhancers. Thus, our results suggest that the primary role of DNA topology in enhancer-regulated βA-globin transcription is to establish enhancer–promoter dependence. The role of a constrained DNA template topology in mediating enhancer control of promoter activity must now be incorporated into a mechanistic description of regulated gene expression. This process may involve direct interaction between distal promoters and enhancers by DNA looping (2, 33), or by the propagation of a structural change through DNA (34, 35), or both. Efforts are currently underway to use these biochemical assays to define how critical erythroid proteins control the complex processes involved in long-range transcriptional regulation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. J. Ma, I. Cartwright, and B. Aronow for a critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by Grant GM 38760 from the National Institutes of Health to B.M.E. and by a National Institutes of Health postdoctoral fellowship to M.C.B., who is also a recipient of an American Cancer Society Junior Faculty Research Award.

ABBREVIATION

- RBC

red blood cells

References

- 1.Bellomy G R, Record M T J. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1990;39:81–128. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60624-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ptashne M. Nature (London) 1986;322:697–701. doi: 10.1038/322697a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herendeen D R, Kassavetis G A, Geiduschek E P. Science. 1992;256:1298–1303. doi: 10.1126/science.1598572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kassavetis G A, Geiduschek E P. Science. 1993;259:944–945. doi: 10.1126/science.7679800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang J C, Giaever G N. Science. 1988;240:300–304. doi: 10.1126/science.3281259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carey M, Leatherwood J, Ptashne M. Science. 1990;247:710–712. doi: 10.1126/science.2405489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schultz M C, Choe S Y, Reeder R H. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2644–2654. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.5.2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laybourn P J, Kadonaga J T. Science. 1992;257:1682–1685. doi: 10.1126/science.1388287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barton M C, Emerson B M. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2453–2465. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.20.2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barton M C, Hoekstra M F, Emerson B M. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:7349–7355. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.24.7349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emerson B M, Nickol J M, Fong T C. Cell. 1989;57:1189–1200. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fong T C, Emerson B M. Genes Dev. 1992;6:521–532. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.4.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd Ed. Plainview NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dynan W S, Jendrisak J J, Hager D A, Burgess R R. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:5860–5865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barton M C, Madani N, Emerson B M. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1796–1809. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.9.1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hawley D K, Roeder R G. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:3452–3461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawley D K, Roeder R G. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:8163–8172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi O B, Engel J D. Cell. 1988;55:17–26. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nickol J M, Felsenfeld G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2548–2552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reitman M, Felsenfeld G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:6267–6271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.17.6267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foley K P, Engel J D. Genes Dev. 1992;6:730–744. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.5.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hesse J E, Nickol J M, Lieber M R, Felsenfeld G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:4312–4316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.12.4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reitman M, Lee E, Westphal H, Felsenfeld G. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3990–3998. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reitman M, Felsenfeld G. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:2774–2786. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.6.2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emerson B M, Lewis C D, Felsenfeld G. Cell. 1985;41:21–30. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emerson B M, Felsenfeld G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:95–99. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Emerson B M. In: Gene Expression: General and Cell-Type-Specific. Karin M, editor. Vol. 1. Boston: Birkhauser; 1993. pp. 116–161. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Evans T, Reitman M, Felsenfeld G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5976–5980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.5976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans T, Felsenfeld G, Reitman M. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1990;6:95–124. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.06.110190.000523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walters M C, Fiering S, Eidemiller J, Magis W, Groudine M, Martin D I K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7125–7129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.7125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walters M C, Magis W, Fiering S, Eidemiller J, Scalzo D, Groudine M, Martin D I K. Genes Dev. 1996;10:185–195. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Majumder S, Miranda M, DePamphilis M L. EMBO J. 1993;12:1131–1140. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05754.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vologodskii A, Cozzarelli N R. Biophys J. 1995;70:2548–2556. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79826-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu H-Y, Tan J, Fang M. Cell. 1995;82:445–451. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90433-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parekh B S, Hatfield G W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1173–1177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]