Abstract

Background

Individuals are reinfected with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) repeatedly. The nature of reinfections in relation to RSV genetic and antigenic diversity is ill defined and has implications to persistence and vaccine control.

Methods

We examined the molecular relatedness of RSV causing primary and repeat infections by phylogenetic analysis of the attachment (G) gene in 12 infants from a birth cohort in rural Kenya, using nasal washings collected over a 16 month period in 2002-03 spanning two successive epidemics.

Results

Six infants were infected in both epidemics, 4 with RSV-A in the first epidemic followed by RSV-B in the second epidemic and 2 infected with RSV-A strains in both epidemics with no significant G gene sequence variability between samples. Two children showed infection and reinfection with different RSV-A strains within the same epidemic. Possible viral persistence was suspected in the remaining 4 infants, although reinfection with same variant cannot be excluded.

Summary

These are the first data specifically addressing strain-specific reinfections in infancy in relation to the primary infecting variant. The data strongly suggest that following primary infection some infants lose strain-specific immunity within 7-9 months (between epidemics) and group-specific immunity within 2-4 months (within an epidemic period).

Keywords: Respiratory syncytial virus, infants, reinfection

Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) causes significant burden of acute respiratory disease during infancy and childhood in both the developed and the developing world, characteristically occurring in recurrent, discrete epidemics[1-3]. First (primary) infection with RSV occurs early in life, usually before the age of 3 years and is associated with a high risk of lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI)[4]. Immunity following primary exposure, however, does not prevent secondary or subsequent infections[5], and reinfections with RSV have been recorded throughout life[6], although associated with lower risk of severe disease[4]. The absence of solid immunity to RSV is likely to be of importance to the persistence of infection within a population and of relevance to the potential impact of future vaccines. However, this phenomenon is inadequately understood. A possible role exists for RSV antigenic and genetic diversity in the reinfection process, although presently this is poorly defined. RSV isolates can be divided into 2 groups, A and B, which are distinct at both the antigenic and nucleotide sequence levels. Both groups often co-circulate in epidemics, but group A isolates more commonly predominate than group B. In addition, the groups can be subdivided into several strains or genotypes which also co-circulate in the epidemics with the predominant strain typically being replaced each year, possibly as a result of localised herd immunity to particular variants[7-10]. The molecular epidemiological evidence suggests that group or genotype infection prevalence influences future transmission of the homologous and heterologous variants within a population; a notion supported by recent mathematical modelling studies[11].

At the individual level, studies of RSV reinfection are few, particularly in the context of the group or genotype of infecting strains. Natural reinfections with the homologous and heterologous group of RSV have been shown. Mufson et al reported 13 children (age range 6-49 months) with RSV infection who were subsequently reinfected at least 9 months later[12]. Six reinfections of group B occurred in ten children initially infected with group A, and two group B reinfections occurred in three children initially infected with group B, data which provide little support for greater homologous than heterologous protection. Sullender et al studied two children (aged 7 and 23 months at first infection) each with sequential (separated by over 1 year) group A virus infections, for whom the attachment (G) protein amino acid sequences of the reinfecting viruses were up to 15% different[6]. In a study of adult volunteers who, following natural infection, were repeatedly challenged with the same strain of virus, Hall et al found that clinical reinfection could occur within a few months of initial exposure[13]. Though experimental, these data raise questions on the strength of homologous protection. Furthermore, a study of hospitalised patients from 1981-1990 in Finland[14] found no direct evidence for homologous protection in the 18 cases of reinfection typed, with occurrence reflecting the predominant group in circulation. Re-admissions with infections with the same RSV group were always within an epidemic. Differentiating repeat infection from delayed clearance of the same infection in the absence of genotyping was not possible.

We have previously described the incidence of RSV infection and risk of associated disease in a birth cohort in the first year of life from Kilifi, Kenya[15]. We now report on the molecular analysis of the viruses from infants within this cohort who experienced primary followed by repeat infections over the course of two sequential epidemics, and compare these data with the viruses characterised from these epidemics from the whole cohort[16].

Materials & Methods

Study population and samples

The study was undertaken in Kilifi District, a rural coastal area of Kenya, and forms part of an epidemiological investigation of RSV through the intensive surveillance of a birth cohort, details of which have been previously described[15;16]. Infants were recruited at or near to birth between January and June 2002, and monitored through active household visits, weekly during epidemic periods and otherwise every 4 weeks, and through passive referral to a research out-patient clinic at the District hospital. The total observation period reported here spanned 16 months and 2 epidemics of RSV.

The first epidemic of this study occurred between March and July 2002 and the second was between December 2002 and March 2003. The epidemic peaks occurred approximately 9 months apart. Nasal washings were collected only from infants experiencing episodes of acute respiratory illness, and then tested for RSV by immunofluorescence (IFAT) as the primary detection method. The severity of disease was assigned as upper respiratory tract infection (URTI), mild pneumonia (LRTI) or severe pneumonia (severe LRTI) based on WHO criteria as described previously[15;17]. All IFAT positives and a proportion of negatives were investigated by molecular methods (described below). The criteria for ascribing a separate RSV infection event were a positive IFAT or RT-PCR nasal washing arising no less than 14 days after a previous positive sample (the interval chosen was based on shedding durations reported by Hall et al[13]; the shedding period was not studied in these infants). Of 338 recruits (yielding 311 child years of observation), 11 individuals had more than one separate RSV infection (one with three infections, the remainder two) identified by IFAT[15]. Typing data were incomplete on two of these individuals who were excluded from this study. Molecular screening of IFAT negative samples yielded an additional 3 children each with a single reinfection. In total, therefore, molecular data exists for 12 children, and are presented here.

RNA Extraction, Amplification, Typing, Sequencing & Analysis

Methods for genetic analysis have been previously described[16]. Briefly, RNA was extracted from the samples using QiAmp Viral RNA kits (Qiagen UK, Ltd), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was synthesised using the Omniscript RT kit (Qiagen UK Ltd). All samples were subjected to RSV/influenza multiplex RT-PCR[18], RSV N gene typing[19] and RSV G gene typing by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP)[16]. G gene amplicons of all RSV positive samples from the 12 infants were sequenced using a Beckman Coulter CEQ 2000XL sequencer and CEQ quick start DECTS cycle sequencing kits (Beckman Coulter UK). Sequences were compared phylogenetically with others from Kilifi District, Kenya and from other countries in sub-Saharan Africa. All G gene sequences were confirmed by re-extraction, RT-PCR and sequencing from the clinical sample.

The Kilifi District repeat infection sample sequences have been deposited into GenBank with accession numbers AY524606, AY524610, AY524614, AY524621, AY524622, AY524625, AY660677, AY660679, AY660681 and AY773286-AY773301 inclusive.

Results

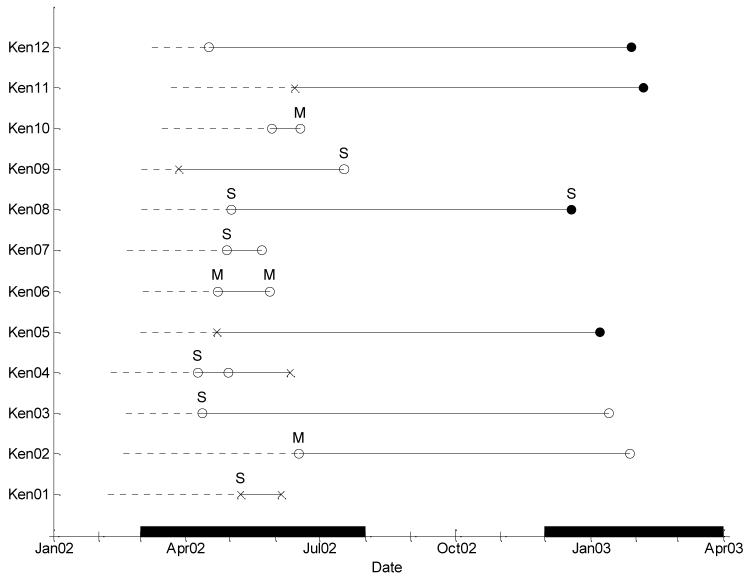

Details of age at infection, and the length of time between, and the clinical status of each RSV infection for the 12 children studied (designated Ken01-Ken12) are given in Table I and Figure 1. Six infants were found to have separate RSV infections in each of the two epidemics and 6 infants were identified with 2 or, in one instance, 3 separate RSV infections in the first epidemic alone. No child experienced reinfections in both epidemics. All infants in this study were in their first year of life, with 2 children being less than 40 days old. Of the 12 primary infections, 7 had LRTI, 5 of which were severe. Of 13 repeat infections (one child had two) 2 involved mild pneumonia and 2 severe pneumonia, and only 1 of the 6 reinfections (children aged 10 or 11 months) in the second epidemic involved the lower respiratory tract (severe case Ken08).

Table I.

Clinical information for each child. Sex is represented by F=female, M=male. Age is represented in days

| Child (sex) | Sample date | Age in days at diagnosis (months)* | Days since last diagnosis (months)* | Clinical statusa | NP type | Genotypeb (Accession number) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ken01 (F) | May 2002 | 90 (3) | - | Severe pneumonia | NP2 | A1 (AY524610) | This child appears to have been infected with virtually identical virus over 28 days |

| Jun 2002 | 118 (4) | 28 (1) | URTI | NP2 | A1 (AY524614) | ||

| Ken02 (M) | Jun 2002 | 119 (4) | - | Mild pneumonia | NP4 | A2 (AY773287) | This child has been infected with very similar virus in 2 epidemics |

| Jan 2003 | 344 (11) | 225 (7) | URTI | NP4 | A2 (AY660679) | ||

| Ken03 (F) | Apr 2002 | 52 (2) | - | Severe pneumonia | NP4 | A2 (AY773286) | This child has been infected with very similar virus in 2 epidemics |

| Jan 2003 | 328 (11) | 276 (9) | URTI | NP4 | A2 (AY660677) | ||

| Ken04 (M) | Apr 2002 | 59 (2) | - | Severe pneumonia | NP4 | A2 (AY773300) | This child was infected with identical virus for 3 weeks and then reinfected with a different group A genotype six weeks later |

| Apr 2002 | 80 (3) | 21 (1) | URTI | NP4 | A2 (AY773301) | ||

| Jun 2002 | 122 (4) | 42 (1) | URTI | NP2 | A1 (AY773288) | ||

| Ken05 (M) | Apr 2002 | 52 (2) | - | URTI | NP2 | A1 (AY773299) | This child was infected with group A virus in the first epidemic and then with group B in the second |

| Jan 2003 | 312 (10) | 260 (9) | URTI | NP3 | B1 (AY773292) | ||

| Ken06 (M) | Apr 2002 | 51 (2) | - | Mild pneumonia | NP4 | A2 (AY773298) | This child was infected with identical virus for 7 weeks |

| May 2002 | 86 (3) | 35 (1) | Mild pneumonia | NP4 | A2 (AY773297) | ||

| Ken07 (F) | Apr 2002 | 68 (2) | - | Severe pneumonia | NP4 | A2 (AY773296) | This child was infected with identical virus for 24 days |

| May 2002 | 92 (3) | 24 (1) | URTI | NP4 | A2 (AY773295) | ||

| Ken08 (M) | May 2002 | 61 (2) | - | Severe pneumonia | NP4 | A2 (AY773290) | This child was infected with group A virus in the first epidemic and then with group B in the second |

| Dec 2002 | 292 (10) | 231 (8) | Severe pneumonia | NP3 | B1 (AY773291) | ||

| Ken09 (F) | Mar 2002 | 25 (1) | - | URTI | NP2 | A1 (AY524606) | This child was infected twice in the first epidemic, with different group A viruses. The second infection was more severe than the first |

| Jul 2002 | 138 (5) | 113 (4) | Severe pneumonia | NP4 | A2 (AY524621) | ||

| Ken10 (F) | May 2002 | 75 (2) | - | URTI | NP4 | A2 (AY773294) | This child was infected with identical virus for 19 days |

| Jun 2002 | 94 (3) | 19 (1) | Mild pneumonia | NP4 | A2 (AY524622) | ||

| Ken11 (F) | Jun 2002 | 84 (3) | - | URTI | NP2 | A1 (AY524625) | This child was infected with group A virus in the first epidemic and then with group B in the second |

| Feb 2003 | 321 (11) | 237 (8) | URTI | NP3 | B1 (AY773289) | ||

| Ken12 (F) | Apr 2002 | 39 (1) | - | URTI | NP4 | A2 (AY773293) | This child was infected with group A virus in the first epidemic and then with group B in the second |

| Jan 2003 | 326 (11) | 287 (9) | URTI | NP3 | B2(60nt)c (AY660681) |

Months rounded to nearest integer.

Clinical Status is indicated according to the definitions of Nokes et al[15]. No child was admitted to hospital.

G gene genotypes are indicated according to the systems previously described[16].

Sample has 60 nucleotide duplication described by Trento et al[24].

Figure 1.

Time course of the RSV infections for each infant from a birth cohort study, Kilifi District, Kenya. Dotted lines represent time from birth to first positive sample. Each symbol represents a positive sample: × – NP2; ● – NP3; ○ – NP4. The letter above each sample represents the clinical status: no letter – URTI; M – mild pneumonia; S – severe pneumonia.

Strain Typing by RFLP

Results of N gene RFLP typing are presented in Table I. All infants were infected with RSV-A strains during the first epidemic (Figure 1). Of the 12 primary infections there were 4 genotype NP2 and 8 genotype NP4. Of the 6 infants with reinfection in the second epidemic, 4 had RSV-B genotype NP3 infections and 2 had RSV-A genotype NP4 infections (same as initial infection). Of these 6 cases, 0 out of 2 infected with the same strain resulted in LRTI, and 1 of 4 infected with group B resulted in severe LRTI. Two of the 6 infants showing repeat RSV diagnosis within the same epidemic were reinfected with a different RSV-A strain (Ken04 NP4 to NP2 and Ken09 NP2 to NP4). The remaining four (Ken01, Ken06, Ken07, Ken10) showed that their infecting virus was of the same group and genotype, and in Ken04 a repeat infection of NP4 preceded the reinfection with NP2. Of the 4 reinfections with the same genotype, 2 resulted in mild pneumonia, and 1 of the 3 reinfections with a different genotype resulted in severe pneumonia. The overall distribution of genotypes of viruses was similar in the infections and reinfections reported here as that previously described for these epidemics[16].

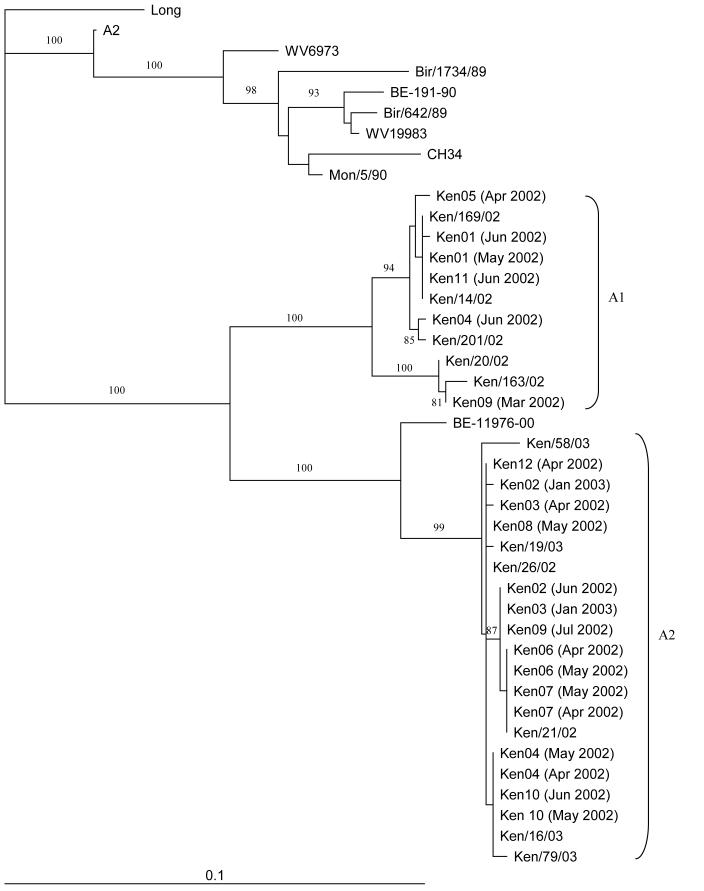

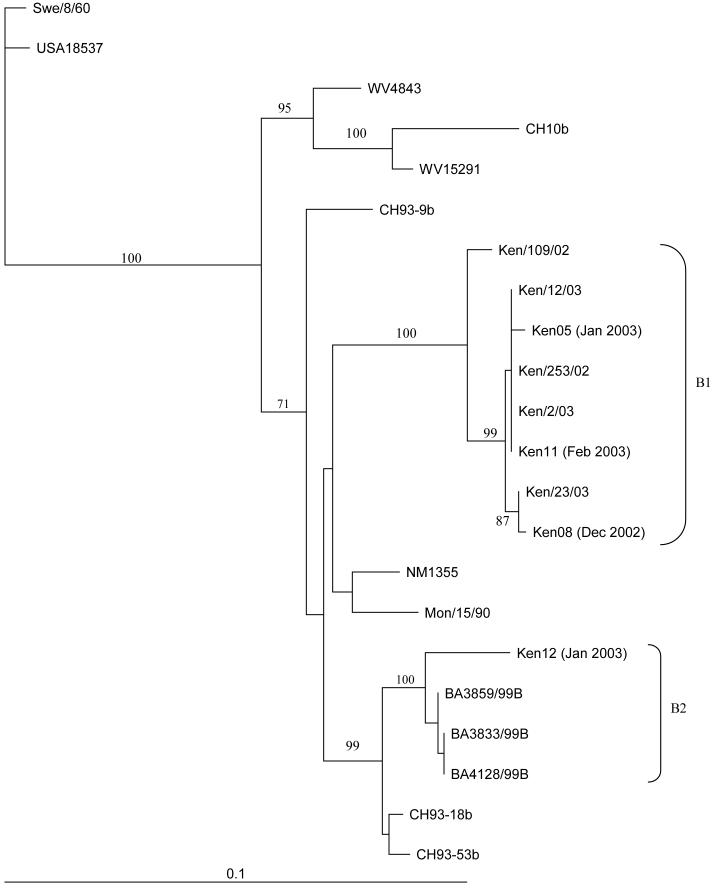

Sequencing & Phylogenetic Analysis of G gene: comparisons with circulating strains in each epidemic

The G genes (nucleotides 284-912 for RSV-A, and 194-915 for RSV-B) from all RSV positive samples (n=25) from each of the 12 infants were sequenced and analysed phylogenetically. Comparisons were made with other samples from Kilifi, published previously[16], as well as reference isolates from around the world. All of these samples were found to cluster with others from Kilifi from the same time-period (Figures 2 and 3, RSV-A and RSV-B, respectively). Six out of 21 samples (28%) clustered with others in cluster A1 and 15/21 (71%) clustered with A2 for RSV-A (Figure 2). Clusters A1 and A2 correspond to previously described RSV genotypes SHL1/3/4 and SHL2[20], or GA2 and GA5, respectively[10;16;21-23].

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree comparing the RSV-A Kilifi District, Kenya reinfection samples with other Kilifi District samples and sequences from Genbank at nucleotides 284-912 of the G gene. Internal node labels represent the bootstrap values for 1000 iterations. Reinfection samples are represented as follows: KenXX, where XX is a two-digit number. Scale bar represents 0.1 nucleotide substitutions per site. Other Kenyan samples from the same epidemics are designated Ken/xxx/yy, where xxx represents a unique sample ID and yy represents the epidemic year.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree comparing the RSV-B Kilifi District, Kenya reinfection samples with other Kilifi District samples and sequences from Genbank at nucleotides 194-915 of the G gene. Internal node labels represent the bootstrap values for 1000 iterations. Reinfection samples are represented as follows: KenXX, where XX is a two-digit number. Scale bar represents 0.1 nucleotide substitutions per site. Other Kenyan samples from the same epidemics are designated Ken/xxx/yy, where xxx represents a unique sample ID and yy represents the epidemic year.

All but one (3/4) of the RSV-B infections (all reinfections) clustered with other Kilifi samples (Figure 3) within the B1 cluster (genotype SAB1[22]). The reinfection sample that was distinct from the others was found to have a 60 nucleotide duplication within the G gene as previously described by Trento et al[24] and belongs to the B2 cluster (genotype BA).

Infants reinfected in separate epidemics

Infant Ken02 showed minor sequence variability between primary and secondary RSV-A infection, seven months apart, with 3/629 non-coding nucleotide changes in the samples. The G gene sequences of the samples from infant Ken03 from each epidemic also had very similar sequences, with 3/629 non-coding nucleotide changes. Both of these infants thus appear to have been infected with the same RSV-A variant (A2, Figure 2), as the G gene sequences were highly similar.

Both Ken05 and Ken11 were infected with an RSV-A A1 variant in the first epidemic and then with an RSV-B B1 virus in the second epidemic (Figures 2 and 3). Infants Ken08 and Ken12 were infected with RSV-A A2 viruses during the first epidemic and then reinfected with RSV-B variants during the second epidemic. Ken08 demonstrated reinfection was with an RSV-B B1 virus, while Ken12’s reinfection was with the only B2 RSV-B variant to be found in this study.

Infants reinfected within the same epidemic

Infant Ken04 was infected with an RSV-A A2 variant, then by A2 again after 3 weeks, followed by an A1 variant within a period of almost two months from the primary infection or 42 days from the date the second A2 strain was identified. Conversely, Ken09 had a primary infection with an RSV-A A1 variant, followed by reinfection with an A2 variant over a period of nearly four months (Table I).

Four other children where multiple samples were taken from within the same season (2002: Ken01, Ken06, Ken07 and Ken10) showed no significant phylogenetic differences in any of the samples (Ken06, Ken07 and Ken10 had no nucleotide changes and Ken01 showed only one coding nucleotide change between the samples). All of the samples for these individuals were taken approximately one month apart, suggesting the possibility that these were prolonged single infections rather than reinfections, as is likely for the two A2 variants identified in Ken04.

Amino acid comparisons between primary and secondary infections

Analysis of the amino acid sequences (codons 91-298 for RSV-A and 60-297 for RSV-B) of all primary and secondary infection samples was carried out (data not shown). All RSV-A sequences were the same length, with the stop codon at the same position and all have 6 potential N glycosylation sites. All but one of these glycosylation sites were shared by all samples examined. The exception was within the carboxy terminus of the gene product and the potential N glycosylation site was moved by one amino acid downstream in samples corresponding to the A1 genotype, represented by NTT in the sequences. The A2 variants had NST in this area. The two children with reinfection with a different variant had clear differences in the G gene deduced amino acid sequences (Ken04 and Ken09). Comparisons of the amino acid sequences within and between patients, showed very little differences where the variant of RSV was the same genotype (maximum 4% and <1% difference for A1 and A2 variants, respectively). Inter-genotype differences were found to be 19%, in the region examined.

The RSV-B amino acid analysis demonstrated that the duplicated sequence was at codons 260-279 of the G gene product and samples from variants without this duplication had a 4 amino acid extension to the end of the gene product, which was not present in RSV-B variants circulating in the previous epidemic, but were representative of the current epidemic. The variants with the duplication have 4 potential N glycosylation sites and those without had 6 sites. Comparisons of the amino acid sequences within and between patients, showed very little difference where the variant of RSV was the same genotype (<1%). However, cross genotype differences were much greater (maximum 20% and 12% difference including and excluding the duplication, respectively).

Discussion

The mechanism by which RSV reinfects the host is unclear. Given that RSV displays considerable genetic and antigenic variation[25], which is thought to be under immune selection[23;26], there is good reason to suppose that RSV group or genotype may play a role in the avoidance of immune recognition, although evidence is very limited at present. The lack of solid immunity following primary infection is of particular importance for the development of effective infant vaccines. Data are therefore specifically required to characterise the relationship between the reinfecting and primary infecting variant. Despite the fact that the sample size was small, the results presented here from a rural coastal region of Kenya provide valuable information on the molecular characteristics of RSV reinfections and the first such study to target the key infant age group. Furthermore, these data provide the most detailed information available to date regarding repeat and persistent infections in the general community, as opposed to hospital inpatient and outpatient based studies[6;12;27] or an adult based study[13]. We show not only reinfection with RSV occurring within the first year of life, but also within the same epidemic, and, importantly, that reinfections can arise with the same variant within the space of 7-9 months and the same group but different variant within the space of 2-4 months. The virus strains in these infants reflect those being detected generally at the time within Kilifi District, Kenya as shown by phylogenetic analysis of G gene data[16]. All RSV G gene sequences from the first epidemic were RSV-A variants, as expected, since this group represented 98% of strains during the 2002 epidemic[16]. Similarly, RSV-B predominated during the second epidemic (61%[16]) and 4/6 samples from the reinfection infants were RSV-B variants. One of these infants demonstrated reinfection with a variant of RSV-B that contained a 60 nucleotide duplication within the G gene that has been previously described[16;24;28]. However, due to the small numbers it is not possible to state whether the presence of this emerging strain of RSV-B has any significance in this community.

Protective immunity can be transient to virus of the same group in some individuals, as suggested by infants Ken04 and Ken09, who showed reinfection with a different strain of RSV-A approximately 2-3 months after the first infection (RSV-A), both during the first epidemic. However, this observation does not preclude the possible existence of some form of genotype specific immunity in the infants reinfected with the heterologous group of virus.

A possible explanation for the 2 infants apparently re-infected with the same virus 7 and 9 months later (Ken02 and Ken03, respectively) is that strain-specific immunity wanes in some individuals over this time period allowing reinfection. Alternatively, these two infants may not have been reinfected, but rather demonstrated very prolonged viral persistence/shedding. However, this would seem unlikely, due to negative RT-PCR results from samples collected between the two infections in each case (data not shown). Experimental reinfection with the same virus within 2 months has been demonstrated in adults[13], so, perhaps it is possible that reinfection did occur in these children. Comparisons of the sequences of the G genes from each of the infections between both children have shown that they are identical. Further analysis would be necessary to ascertain whether this particular RSV strain is prone to immune evasion, especially in light of RT-PCR and IFAT negative intermediate samples.

The remaining four children (and the first two samples from Ken04) with the same G gene amino acid sequences in samples collected one-month apart implies that viral persistence can occur for at least one month. For infants for whom prolonged shedding was a possibility (Ken 01-04, 06, 07, 10) we investigated potential predisposing factors from outpatient and KDH admission records; no relevant underlying conditions such as congenital disease, malnutrition, or immunocompromised state, were identified.

Repeat analysis from all nasal washings yielded the same sequences as those presented here so errors in the RT-PCR and sequencing are unlikely. Consequently, the two individuals showing reinfection with a different RSV-A strain in the same epidemic (Ken04 and Ken09) were probably reinfected, as opposed to coinfected with both strains at the same time. This was also highlighted by the NP typing in these two individuals, where only one N gene pattern was noted at any one time.

Most of the amino acid variation was associated with the variable regions flanking the conserved cysteine rich domain, as expected. The significance of occasional amino acid differences between samples of the same genotype is not known, but may be a result of the host immune pressure on the virus during the course of infection.

Susceptibility to reinfections with RSV is a result of the individual immunity to previous infections and the currently circulating strains. Thus individual risks of reinfections are combinations of factors of both the individual child (immunity and previous exposure) and the population (previous circulating strains and current circulating strains). The factors at the population level are determined by the individuals within the population, for example the most parsimonious explanation for strain replacement between epidemics is that it is driven by individual (homologous) immunity. However, that the RSV variants in each of the two epidemics reported here are similar (and in the case of two infants, reinfection occurred with identical variants) makes interpretation of the transmission and genetic dynamics less straightforward.

Further information on the pattern of infection and reinfection observed may be provided by the families of these individuals, but this data is not available for this particular cohort.

It should also be noted that, in the case of influenza, there is the hypothesis of “original antigenic sin” that suggests that the response to secondary (and subsequent) infections can depend at least partially on the immune response towards the primary infection. This may be the case for RSV, but many more reinfections would need to be studied in order to elucidate this.

In summary, we have demonstrated multiple RSV infections in the first year of life in a community study of a birth cohort. In two consecutive seasons, and separated by a gap of by 7-9 months, some infants were apparently reinfected with the same strain, while others were reinfected with the heterologous group (RSV-A followed by RSV-B). Within the same epidemic, we observed infection and reinfection with different RSV-A strains within 2-4 months, suggesting transient immunity to the homologous group of RSV in some individuals. These data are important in questioning the nature of immunity to re-infection in relation to the primary infecting and re-infecting variant in the infant.

Acknowledgements

We thank the study volunteers for generous participation. We thank also the RSV team for tireless work and enthusiasm, and research outpatient clinic field workers and clinical officers, paediatric ward, maternity and MCHC staff, and senior hospital staff from Kilifi District Hospital for support and cooperation in the running of this study. The manuscript is published with permission of the Director of the Kenya Medical Research Institute. This work was supported by The Wellcome Trust (Grant Number: 061584).

(4) Funded by the Wellcome Trust (United Kingdom) (grant ref: 061584).

Footnotes

Presented in part: Research in Progress Short Presentations and Posters, Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, London, UK. December 2004

Informed consent for participation in the study was obtained from each infant’s mother. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the KEMRI/National Ethical Review Committee, in Kenya (Protocol No. 594) and Coventry Research Ethics Committee, in the UK (No. 025/09/00).

No conflict of interest exists for any of the authors.

No changes of affiliations.

Reference List

- [1].Weber MW, Mulholland EK, Greenwood BM. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in tropical and developing countries. Trop Med Int Health. 1998;3:268–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Simoes EA. Respiratory syncytial virus infection. Lancet. 1999;354:847–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)80040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Robertson SE, Roca A, Alonso P, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infection: denominator-based studies in Indonesia, Mozambique, Nigeria and South Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:914–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Glezen WP, Taber LH, Frank AL, Kasel JA. Risk of primary infection and reinfection with respiratory syncytial virus. Am J Dis Child. 1986;140:543–6. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1986.02140200053026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Henderson FW, Collier AM, Clyde WA, Jr., Denny FW. Respiratory-syncytial-virus infections, reinfections and immunity. A prospective, longitudinal study in young children. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:530–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197903083001004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sullender WM, Mufson MA, Prince GA, Anderson LJ, Wertz GW. Antigenic and genetic diversity among the attachment proteins of group A respiratory syncytial viruses that have caused repeat infections in children. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:925–32. doi: 10.1086/515697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cane PA. Molecular epidemiology of respiratory syncytial virus. Rev Med Virol. 2001;11:103–16. doi: 10.1002/rmv.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Loscertales MP, Roca A, Ventura PJ, et al. Epidemiology and clinical presentation of respiratory syncytial virus infection in a rural area of southern Mozambique. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:148–55. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200202000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cane PA, Matthews DA, Pringle CR. Analysis of respiratory syncytial virus strain variation in successive epidemics in one city. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1–4. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.1.1-4.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Peret TC, Hall CB, Schnabel KC, Golub JA, Anderson LJ. Circulation patterns of genetically distinct group A and B strains of human respiratory syncytial virus in a community. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:2221–9. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-9-2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].White LJ, Waris M, Cane PA, Nokes DJ, Medley GF. The transmission dynamics of groups A and B human respiratory syncytial virus (hRSV) in England & Wales and Finland: seasonality and cross-protection. Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133:279–89. doi: 10.1017/s0950268804003450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Mufson MA, Belshe RB, Orvell C, Norrby E. Subgroup characteristics of respiratory syncytial virus strains recovered from children with two consecutive infections. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:1535–9. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.8.1535-1539.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hall CB, Walsh EE, Long CE, Schnabel KC. Immunity to and frequency of reinfection with respiratory syncytial virus. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:693–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.4.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Waris M. Pattern of respiratory syncytial virus epidemics in Finland: two-year cycles with alternating prevalence of groups A and B. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:464–9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.3.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Nokes DJ, Okiro EA, Ngama M, et al. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Epidemiology in a Birth Cohort from Kilifi District, Kenya: Infection during the First Year of Life. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:1828–32. doi: 10.1086/425040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Scott PD, Ochola R, Ngama M, et al. Molecular epidemiology of respiratory syncytial virus in Kilifi district, Kenya. J Med Virol. 2004;74:344–54. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].WHO . Management of the child with a serious infection or severe malnutrition: guidelines for care at the first-referral level in developing countries. Geneva: WHO; 2000. WHO/FCH/CAH/00/1. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Stockton J, Ellis JS, Saville M, Clewley JP, Zambon MC. Multiplex PCR for typing and subtyping influenza and respiratory syncytial viruses. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2990–5. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.2990-2995.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cane PA, Pringle CR. Molecular epidemiology of respiratory syncytial virus: rapid identification of subgroup A lineages. J Virol Methods. 1992;40:297–306. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(92)90088-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Cane PA. Analysis of linear epitopes recognised by the primary human antibody response to a variable region of the attachment (G) protein of respiratory syncytial virus. J Med Virol. 1997;51:297–304. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199704)51:4<297::aid-jmv7>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Peret TC, Hall CB, Hammond GW, et al. Circulation patterns of group A and B human respiratory syncytial virus genotypes in 5 communities in North America. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1891–6. doi: 10.1086/315508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Venter M, Madhi SA, Tiemessen CT, Schoub BD. Genetic diversity and molecular epidemiology of respiratory syncytial virus over four consecutive seasons in South Africa: identification of new subgroup A and B genotypes. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:2117–24. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-9-2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zlateva KT, Lemey P, Vandamme AM, Van Ranst M. Molecular evolution and circulation patterns of human respiratory syncytial virus subgroup a: positively selected sites in the attachment g glycoprotein. J Virol. 2004;78:4675–83. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.9.4675-4683.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Trento A, Galiano M, Videla C, et al. Major changes in the G protein of human respiratory syncytial virus isolates introduced by a duplication of 60 nucleotides. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:3115–20. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19357-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sullender WM. Respiratory syncytial virus genetic and antigenic diversity. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:1–15. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.1.1-15.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Woelk CH, Holmes EC. Variable immune-driven natural selection in the attachment (G) glycoprotein of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) J Mol Evol. 2001;52:182–92. doi: 10.1007/s002390010147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kawasaki Y, Hosoya M, Katayose M, Suzuki H. Role of serum neutralizing antibody in reinfection of respiratory syncytial virus. Pediatr Int. 2004;46:126–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-200x.2004.01860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Nagai K, Kamasaki H, Kuroiwa Y, Okita L, Tsutsumi H. Nosocomial outbreak of respiratory syncytial virus subgroup B variants with the 60 nucleotides-duplicated G protein gene. J Med Virol. 2004;74:161–5. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]