Abstract

Dendritic cells (DC) are specialized in the presentation of antigens and the initiation of specific immune responses. They have been involved recently in supporting innate immunity by interacting with various innate lymphocytes, such as natural killer (NK), NK T or T cell receptor (TCR)-γδ cells. The functional links between innate lymphocytes and DC have been investigated widely and different studies demonstrated that reciprocal activations follow on from NK/DC interactions. The cross-talk between innate cells and DC which leads to innate lymphocyte activation and DC maturation was found to be multi-directional, involving not only cell–cell contacts but also soluble factors. The final outcome of these cellular interactions may have a dramatic impact on the quality and strength of the down-stream immune responses, mainly in the context of early responses to tumour cells and infectious agents. Interestingly, DC, NK and TCR-γδ cells also share similar functions, such as antigen uptake and presentation, as well as cytotoxic and tumoricidal activity. In addition, NK and NK T cells have the ability to kill DC. This review will focus upon the different aspects of the cross-talk between DC and innate lymphocytes and its key role in all the steps of the immune response. These cellular interactions may be particularly critical in situations where immune surveillance requires efficient early innate responses.

Keywords: DC, NK, NK T cells, TCR-γδ cells

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DC), characterized as the most potent antigen-presenting cells (APC), represent a multi-functional population of cells (Table 1). Conventional DC subsets described in humans include myeloid DC (mDC) CD11c+ BDCA1+ and plasmacytoid DC (pDC) CD11c− BDCA2+ (CD303+) whereas, in mice, the corresponding subsets are CD11c+ CD8a−CD11b+ and CD11cloB220+Ly6C−CD11b− respectively [1–3]. The two subsets differ in their expression of highly conserved microbial pattern recognition receptors, known as Toll-like receptors (TLR), but both are able to induce the stimulation of naive T cells. In mice, a small population of mDC can express CD8 [2]. These splenic CD8+ DC are able to cross-present antigen to T cells in vitro, in contrast to CD8− DC [4]. No equivalent CD8+ DC subpopulation has been described in humans, but Langerhans cells (LC), a particular DC population in the skin of mice and humans, also display good cross-presentation capabilities [5]. In steady-state conditions, DC are in an immature stage and induce tolerogenic T cell responses [6,7]. In an inflammatory microenvironment, upon ligand recognition by TLR, maturation process occurs and DC migrate to the lymph nodes where productive immune responses are induced [8,9]. Recent reviews highlighted the role of inflammation signals on DC differentiation [10] and on the pro- or anti-inflammatory effects of DC [11,12].

Table 1.

Populations of DC in mice and humans.

| DC subsets | Tissue distribution | Species | Immature phenotype | Mature phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone marrow derived DC | Dermis, airways, intestine, thymus, spleen, liver, lymphoid tissue | Mouse | CD11c+CD8α− CD11b+MHC-II+ TLR-1–3+/−TLR-2,4–9+ | CD83+ CCR7+ CD80++ CD86++ MHC-II++ |

| Human | CD1a+ CD14−CD11c++CD11b++ CD1c+ CD209+ MHC-II+ TLR-1, 6+,3,8++ | CD40+ | ||

| Plasmacytoid DC | Lymphoid organs, liver, lung, skin | Mouse | CD11c+/−B220+Ly−6C+CD11b− PDCA+ MHC-II+ TLR-2–9+ | |

| Human | CD14−CD11c−CD123++ BDCA2+ ILT7+ MHC-II+ TLR-7,9++ | |||

| CD8α+DC | Thymus, spleen, lymph node, liver | Mouse | CD8α+CD4−CD11c++ CD11b CD205++-TLR-2–4,6,8,9+ | |

| Human | Not identified | |||

| Langerhans cells | Mucosal epithelia, epidermis | Mouse | CD8α− CD11c+ CD205++ E-cadherin+CD207+ | E-cadherin +/− |

| Human | CD14+/−CD11c+CD1a+ E-cadherin+CD207+CCR6+ |

DC, dendritic cells. +/−, low; ++, high.

In addition to their role in induction of adaptive immune responses, DC also activate natural killer (NK) cells [13]. More recently, this DC activation was extended to other cell types such as NK T or T cell receptor (TCR)-γδ cells [14,15]. Moreover, certain DC subsets share common developmental pathways with NK cells, suggesting that these cells could influence each other during differentiation [16–18].

Natural killer, NK T and TCR-γδ lymphocytes constitute particular populations of lymphocytes which play important roles in innate immunity and share similar functions upon activation, such as expansion, secretion of soluble factors (cytokines, chemokines) and cytolytic activity [19–22].

The functions of NK cells are the result of activating and inhibitory signals received from their receptors (Table 2), which can sense viral infections, as well as modified self-antigens. In contrast to cytolytic T cells, these cells do not require specific antigen recognition to acquire the ability to kill target cells. Two different functional subsets of NK cells can be distinguished in humans regarding the expression of CD56 molecule, NK CD56low-non-cytolytic and NK CD56high-cytolytic respectively [23]. Mouse NK cells do not express CD56 and were subdivided recently according to CD27 expression [24]. After activation, which can be dependent upon DC, NK cells proliferate, produce interferon (IFN)-γ and acquire cytolytic activity.

Table 2.

Innate lymphocyte receptors.

| Species | Ligands | Function | NK NKp46+ CD3– | NK T Particular Vα TCR | γδT TCR-γδ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KIR | h | HLA-A,B,C allotypes | Activation and inhibition | + | + | + |

| Ly49 | m | MHC class I | Activation and inhibition | + | + | Subset |

| NKG2A-C/CD94 | h | HLA-E | Inhibition | + | ? | + |

| m | Qa-1 | Inhibition | + | ? | ? | |

| NKG2D | h | MICA/B, RAET | Activation | + | ? | + |

| m | RAET | Activation | + | ? | ? | |

| NCR (NKp30,44) | h | Virus? | Activation | + | ? | Subset |

| CD16 | h, m | Immune complexes | Activation | + | – | – |

| CD161 | h, m | Clr-g, Clr-b | Activation and inhibition | + | + | ? |

| CD27 | h, m | CD70 | Activation | + | ? | ? |

HLA, human leucocyte antigen; MICA/B, major histocompatibility complex class I-related; NK, natural killer; TCR, T cell receptor, MHC, major histocompatibility complex; h, human; m, mouse; RAET, retinoic acid early transcript.

Natural killer T lymphocytes are T lymphocytes expressing several NK markers (Table 2) and bearing an invariant TCR (Vα14Jα28 gene segments in mice and Vα24JαQ in humans). Both self and microbial glycolipids presented on non-polymorphic CD1d molecules can induce NK T activation [25]. Upon activation, they produce type 1 as well as type 2 cytokines and display cytotoxic activity [21]. Therefore, NK T cells are involved in a large number of immune responses such as autoimmunity [26] and immunity against viral [27], bacterial [28], fungal [29], parasitic pathogens [30] and tumours [31].

T cell receptor-γδ T cells differ from the classical αβ T lymphocytes by a TCR with unique structural and antigen-binding features [20], that endows them with independence of any APC for the recognition of foreign epitopes [32]. Each tissue has its own specific subset of TCR-γδ cells, according to the variable (V) gene used to generate the TCR [33]. Various populations of TCR-γδ cells reside in the peripheral tissues of mice, including the skin, gut and uterus. However, in humans, tissue-specific TCR-γδ cells are not as prominent and the adult human TCR-γδ cell repertoire is dominated by a polyclonal population bearing the Vγ9Vδ2 TCR. TCR-γδ cells recognize phosphorylated isoprenoid precursors and alkylamines, which are conserved in the metabolic pathways of many species including plants, pathogens and primates [34]. In the periphery, TCR-γδ cells express mainly the Vδ1 TCR [35]. TCR-γδ cells are key players in innate immunity and, arguably, the most complex and advanced cellular representative of the innate immune system [36].

However, a clear distinction between these innate lymphocyte populations is difficult, because of overlapping of some specific markers. Expression of NK1·1, NKG2D, Ly49, 2B4 and NKp46 receptors were detected on TCR-γδ cells, while non-rearranged germline TCR-δ locus transcripts were present in mature NK cells [37]. Similarly Vα14 activated NK T cells can down-regulate CD3/TCR, which renders them indistinguishable from NK cells [38].

The interactions between DC and innate lymphocytes have been documented both in mice and humans. This review will focus upon the different aspects of this cross-talk and its key role in all steps of an immune response, such as differentiation, maturation, effector stage and control.

Innate lymphocyte ability to modulate the differentiation of DC

It has been suggested that DC differentiation can be influenced by interactions with other immune cells, such as NK cells, in the inflammatory environment of rheumatoid arthritis joints [39,40]. In mice, NK cells are able to inhibit myelopoesis in autologous host [41,42]. Moreover, NK depletion resulted in increased numbers of myeloid precursors in the spleen, but not in the bone marrow, suggesting that NK cells serve as regulators of myelopoesis [41,43]. Soluble factors such as granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and interleukin (IL)-3, which are produced mainly by resting NK, stimulate colony formation, while tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, secreted after NK activation, exerts inhibitory effects [44].

Most studies focused upon the role of NK cells in the maturation of immature DC differentiated in vitro in the presence of cytokines [45–47]. In contrast to IL-4 differentiated cultures, DC derived from monocyte-enriched peripherasl blood mononuclear cells, in the presence of IFN-α, require NK cells for complete maturation as shown by CD83, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II and co-stimulatory molecules up-regulation and priming of efficient antitumour CD8+ T cell responses [48].

A recent study investigated the role of NK cells in an early stage of DC differentiation from CD14+ monocyte precursors. Co-culturing these cells with autologous NK cells in the presence of IL-15 induced morphological and phenotypic changes associated with DC, such as down-regulation of CD14, up-regulation of CD40, CD80, CD86, DC-SIGN, DEC 205 and antigen uptake. The process requires cell–cell contact between NK and monocytes, as well as soluble factors, such as GM-CSF and CD40L (CD154), produced by NK cells. CD3− KIR− CD56bright NK cells were shown to be more efficient in inducing DC differentiation when compared with CD56dim counterparts, suggesting that the process might occur in lymph nodes. Supporting the hypothesis that this process occurs in vivo, synovial fluid from patients with rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis (containing IL-15) was able to induce DC differentiation only in the presence of freshly isolated autologous NK cells. Therefore, NK have been proposed as crucial for maintaining inflammatory diseases by providing a milieu for monocytes to differentiate towards DC [40].

Dendritic cell-innate lymphocyte cross-talk in the activation of the immune response

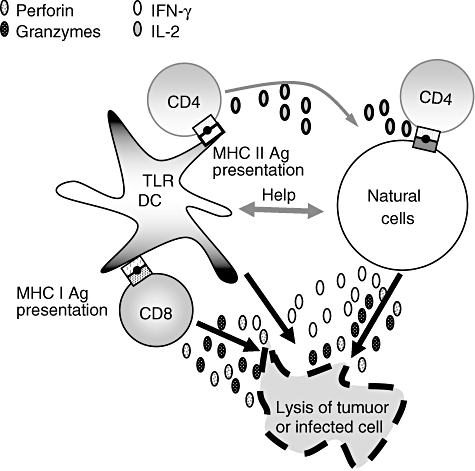

The role of DC-innate lymphocytes cross-talk in the activation of the immune response is illustrated in Fig. 1. The first evidence for innate immunity stimulated by DC was provided by the work of Fernandez et al. [13], which showed a direct activation of NK cells by DC in vivo. Subsequently, NK cell activation in vitro has been documented by using a variety of mouse or human DC [19]. Most studies focused upon the interactions between NK cells and mDC and only recently upon the interaction with pDCs [49]. Monocytes-derived DC appear as the most potent stimulators of NK cell proliferation and cytotoxicity. Human dermal DC have intermediate effects and LC are able to activate NK cells only in the presence of exogenous IL-2 and IL-12 [50]. Moreover, mDC and pDC isolated from peripheral blood are both able to activate NK cells after stimulation with different TLR ligands [51,52].

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of dendritic cell (DC)-innate lymphocyte cross-talk in the activation of the immune response. pDC, plasmacytoid DC; IL, interleukin; IFN, interferon; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; TLR, Toll-like receptors; mDC, myeloid DC; NK, natural killer; NKT, natural killer T; TCR, T cell receptor; HLA-DR, human leucocyte antigen-DR.

The DC-induced activation of resting NK cells in vitro requires direct cell contact resulting in a polarized secretion of pre-assembled stores of IL-12 by DC towards NK cells within the synapse between both cell types [53]. In synergy with IL-12, IL-15Rα expression on DC was shown to be required for NK cells priming [54]. Subsequently, the DC/NK interactions were found to be multi-directional, involving not only cell–cell contact but also soluble factors [49]. Cytokines such as IL-2, IL-18 and type I IFN play crucial roles in this cross-talk [55–57]. These results suggest that different DC subsets activate NK cells at several steps of the immune response, with the pDC promoting early activity of NK cells followed by mDC. Early release of IL-12 by pathogen-activated DC could be the link between NK/mDC and NK/pDC interactions [52]. Conversely, NK can activate DC optimally in vitro. This process requires both cell–cell contact, mediated via the receptors NKp30, KIR or NKG2A [58], and TNF-α production [47].

Similar to NK/DC cross-talk, bidirectional interactions take place between DC and NK T. Responses of NK T cells to synthetic α-GalCer presented by CD1d molecules on DC requires IL-12 production by DC and CD40/CD40 ligand-mediated cell contacts [59]. Conversely, CD40 signalling and the release of TNF-α and IFN-γ induce DC maturation [60]. Despite the expression of CD1d, NK T activation by mDC does not occur unless the DCs are activated through TLRs [61,62]. DC maturation induced by TLR stimuli is enhanced by NK T cells [63,64]. pDC stimulated through TLR-9 induce NK activation markers and licence these cells to respond to antigen loaded mDC [65]. These data suggest that NK T cells interact with DC subsets (mDC and pDC) and contribute to the outcome of immune responses after pDC activation.

A mutually co-stimulatory relationship was also found between TCR-γδ cells and DC. Activation of TCR-γδ cells by phosphoantigens induces a significant up-regulation of CD86 and MHC class I molecules and the acquisition of functional features typical of mature/activated DC [66]. Cell–cell contacts are required for stimulation with aminophoshonate, but not with phoshomonoesters. In return, DCs induce CD25 and CD69 up-regulation on TCR-γδ cells, as well as IFN-γ and TNF-α secretion by TCR-γδ cells [66]. Moreover, TCR-γδ cells enhance DC maturation induced by TLR-2 and TLR-4 ligands [67,68]. Another study showed that freshly isolated TCR-γδ cells were as efficient as those activated by phosphoantigens in inducing maturation of DCs and IL-12 production by DC [69].

Dendritic cell-innate lymphocytes cross-talk is exploited to achieve reciprocal full activation, with DC maturation being a sensor that links innate immune responses and adaptive ones (Fig. 1). The final outcome of these cellular interactions may have a dramatic impact on the quality and strength of the down-stream immune responses.

Dendritic cell-innate lymphocyte cross-talk in the induction and effector phases of adaptive immune responses

Dendritic cells and innate lymphocytes in effector phases of the immune responses are summarized in Fig. 2. DC maturation by innate lymphocytes is relevant in early responses to tumour cells and certain viruses, when the absence of inflammation and pathogen-associated molecules does not result in DC maturation and subsequent antigen presentation [51,70]. In addition, the interaction between mature, but not immature DC, results in innate lymphocyte proliferation, IFN-γ production and cytolytic activity against tumours, virus or pathogen-infected cells [13,45]. Therefore, these interactions play an important role in the induction of early immune responses to tumours, pathogens and certain viruses, before an adaptive immune response can be developed. Moreover, this cross-talk bridges innate and adaptive immunity, as it affects the magnitude and polarization of T cell-mediated responses.

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of dendritic cell (DC)-innate lymphocyte cross-talk in the effector phase of the immune response. IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; TLR, Toll-like receptors; MHC, major histocompatibility complex.

In lymph nodes, NK cells may play an important role in the initiation of specific T cell responses by influencing DC maturation. Indeed, under in vitro conditions where DCs are activated suboptimally with type-I IFN, NK cells licence DC to prime T cell responses [48]. Consequently, mature DCs activate NK to produce IFN-γ, which is required for T helper 1 (Th1) polarization [71,72]. In some cases, T cell-mediated tumour rejection is dependent upon DC activation by NK cells [73]. Furthermore, Adam et al. [74] reported that NK cell–DC cross-talk may bypass the Th arm in CTL induction against tumours expressing NKG2D ligands. A critical role for NKG2D-mediated NK–DC interaction in generating robust CD8+ T cell immunity against intracellular parasites was also documented [75].

Antigen-specific, IFN-γ-producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells could also be induced down-stream of interactions between NK T and antigen-capturing DC. These data suggest that DC activated by a population of innate lymphocytes, such as NK T cells, can activate another group of innate lymphocytes, such as NK cells, to induce anti-tumour effects [59,63]. TCR-γδ are also activated by DC infected in vitro by the bacillus Calmette–Guérin, as indicated by elevated CD69 expression on their cell surface, IFN-γ secretion and cytotoxic activity. Consequently, DC-stimulated TCR-γδ cells help DCs to prime a significantly stronger anti-mycobacterial CD8 T cell response [14]. TCR-γδ cells activated by the synthetic phosphoantigen bromohydrin pyrophosphate induce the production of IL-12 by DC, an effect involving IFN-γ production. The relevance of this finding to DC function was demonstrated by the increased production of IFN-γ by alloreactive T cells when stimulated in a mixed leucocyte reaction with DC preincubated in the presence of activated TCR-γδ cells. These data suggest that TCR-γδ cell activation results in DC maturation and enhanced TCR-αβ T cell responses [69].

Moreover, DC and innate lymphocytes share similar functions. As well as their APC function, DC may acquire cytotoxic properties [76,77], for example in response to stimulation with type I IFN [78]. In fact, human DC can induce in vitro growth arrest and apoptosis of tumour cells [77,79,80]. DC able to kill tumour cells have also been described in rat models [81]. Cytotoxic DC activity seems to be independent of Fas-associated death domain but dependent upon caspase-8 [77], whereas the inhibiting effect of DC on tumour proliferation is likely to be caspase-8 independent and does not require cell contact [80].

Last year, Taieb et al. [82] described a new subset of murine DC expressing NK markers and producing large amounts of IFN. These cells killed cells lacking self-MHC molecules in a TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-dependent manner and they have been named ‘IFN-producing killer dendritic cells (IKDC)’[83]. They have been described as a distinct cell population because they differ in their developmental origin, because Rag2−/−IL2rg−/− mice lack canonical NK cells but possess functional IKDC in the spleen [82]. However, very recently several groups have shown that these cells were, in fact, activated NK cells [84–86].

Other types of DC-bearing NK cell receptors have been identified, such as bitypic cells expressing both CD11c and the NK cell marker DX5 in the context of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection [87]. In a mouse autoimmune diabetes model, treatment with CD40L induces the presence of this bitypical NK/DC regulatory cell population [88]. These cells can kill NK sensitive target cells and present ovalbumin antigen [88].

On the other hand, activated NK cells could become potent APC [89]. After activation, NK cells can up-regulate MHC class II, CD80, and CD86 molecules and acquire independent unique mechanisms of antigen capture and presentation, involving activating receptors such as NKp46, NKp30 and NKG2D [89]. NK cells may also acquire functional APC-like properties after target-cell killing [89]. Studies on the T cell-activating potential of human NK cells in different clinical conditions revealed that a proinflammatory, but not immunosuppressive, microenvironment can up-regulate T cell-activating molecules on NK cells [89]. Even a subtype of TCR-γδ cells (Vδ2+ T cells) upon microbial activation can display antigen and provide enough co-stimulatory signals to induce a strong naive αβ T cell proliferation and differentiation [90]. TCR-γδ cells also express DC activation markers, such as MHC class II, CD80 and CD86 [91]. Expression of MHC class II and ligands for T cell co-stimulatory molecules is not a guarantee for APC capability as eosinophils, for example, express significant levels of MHC class II and CD86 on their surface after activation but cannot process antigen [92]. The APC function of TCR-γδ cells seems to be associated with the expression of CCR7, allowing their migration to lymph nodes. This expression is early, but transient [93], suggesting that the APC function of TCR-γδ cells may be more effective in the early stage of antimicrobial immune processes. The mechanisms controlling antigen uptake and processing in these cells are, however, still unknown and because in vivo studies are understandably difficult to perform in humans, there is no evidence that these cells function as APC.

Dendritic cell-innate lymphocytes in the control of immune responses

Recently, a novel function was assigned to NK cells, that involves them in ‘DC editing’. This process is mediated by NK aggression of normal immature DC. Only DCs undergoing optimal maturation become refractory to NK killing and are allowed to prime Th1 cells after migration to the lymph nodes [94]. In bacterial infections, interactions between NK cells and DC result in the rapid induction of NK cell activation and in the lysis of uninfected DC [95].

Among NK receptors, NKp30 seems to play an important role in the maturation and control of DC apoptosis, whereas the up-regulation of human leucocyte antigen-E (HLA-E) expression on DC protects them from NK lysis through the CD94/NKG2A receptor [96]. The interactions betweenNK cells and DC via NKp30 differ according to the ratio between NK cells and DC. A low NK/DC (1:5) ratio results in DC activation, whereas at a high (5:1) ratio, NK cells kill immature DC [45,47]. In contrast, pDC seem to display an intrinsic resistance to lysis by NK cells but exposure of pDC to IL-3 increases their susceptibility to NK cell cytotoxicity [49]. Until now, DC killing by NK cells in vivo has been demonstrated only in murine transgenic [97] or transplantation models, with no evidence so far that DC killing occurs in vivo under normal physiological conditions.

Like NK cells, NK T cells could also, under certain conditions, kill both immature and mature DC. These cells expressing inhibitory NK receptors are restricted by HLA-E molecules and are able to kill most NK-susceptible tumour cell lines [98]. Interestingly, in Leishmania infantum infections, immature DC up-regulate CD1d and are killed efficiently by NK T cells, whereas they are resistant to NK cell-mediated lysis because of an up-regulation of HLA-E expression which protects them through the inhibitory receptor CD94/NKG2A [99].

In conclusion, there is accumulating evidence that DC- innate lymphocyte interactions are multi-directional, playing important roles in differentiation, maturation, effector phases and control of immune responses. After activation, innate lymphocytes are able to induce DC maturation and therefore to shape both innate immune reactions in inflamed tissues and adaptive immune responses in lymph nodes. These cellular interactions may be particularly critical in situations where immune surveillance requires efficient early innate responses.

References

- 1.Colonna M, Trinchieri G, Liu YJ. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells in immunity. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1219–26. doi: 10.1038/ni1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shortman K, Naik SH. Steady-state and inflammatory dendritic-cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:19–30. doi: 10.1038/nri1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sumpter TL, Abe M, Tokita D, Thomson AW. Dendritic cells, the liver, and transplantation. Hepatology. 2007;46:2021–31. doi: 10.1002/hep.21974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.den Haan JM, Lehar SM, Bevan MJ. CD8(+) but not CD8(-) dendritic cells cross-prime cytotoxic T cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1685–96. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.12.1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ratzinger G, Baggers J, de Cos MA, et al. Mature human Langerhans cells derived from CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors stimulate greater cytolytic T lymphocyte activity in the absence of bioactive IL-12p70, by either single peptide presentation or cross-priming, than do dermal-interstitial or monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:2780–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.4.2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–52. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinman RM, Hawiger D, Nussenzweig MC. Tolerogenic dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:685–711. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ito T, Wang YH, Liu YJ. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors/type I interferon-producing cells sense viral infection by Toll-like receptor (TLR) 7 and TLR9. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2005;26:221–9. doi: 10.1007/s00281-004-0180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lutz MB, Schuler G. Immature, semi-mature and fully mature dendritic cells: which signals induce tolerance or immunity? Trends Immunol. 2002;23:445–9. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02281-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sabatte J, Maggini J, Nahmod K, et al. Interplay of pathogens, cytokines and other stress signals in the regulation of dendritic cell function. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2007;18:5–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cools N, Ponsaerts P, Van Tendeloo VF, Berneman ZN. Balancing between immunity and tolerance: an interplay between dendritic cells, regulatory T cells, and effector T cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:1365–74. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0307166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ueno H, Klechevsky E, Morita R, et al. Dendritic cell subsets in health and disease. Immunol Rev. 2007;219:118–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez NC, Lozier A, Flament C, et al. Dendritic cells directly trigger NK cell functions: cross-talk relevant in innate anti-tumor immune responses in vivo. Nat Med. 1999;5:405–11. doi: 10.1038/7403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dieli F, Caccamo N, Meraviglia S, et al. Reciprocal stimulation of gammadelta T cells and dendritic cells during the anti-mycobacterial immune response. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:3227–35. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi T, Chiba S, Nieda M, et al. Cutting edge: analysis of human V alpha 24+CD8+ NK T cells activated by alpha-galactosylceramide-pulsed monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:3140–4. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blom B, Spits H. Development of human lymphoid cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:287–320. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marquez C, Trigueros C, Franco JM, et al. Identification of a common developmental pathway for thymic natural killer cells and dendritic cells. Blood. 1998;91:2760–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perez SA, Sotiropoulou PA, Gkika DG, et al. A novel myeloid-like NK cell progenitor in human umbilical cord blood. Blood. 2003;101:3444–50. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamerman JA, Ogasawara K, Lanier LL. NK cells in innate immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayday AC. [Gamma][delta] cells: a right time and a right place for a conserved third way of protection. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:975–1026. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lauwerys BR, Garot N, Renauld JC, Houssiau FA. Cytokine production and killer activity of NK/T–NK cells derived with IL-2, IL-15, or the combination of IL-12 and IL-18. J Immunol. 2000;165:1847–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vivier E. What is natural in natural killer cells? Immunol Lett. 2006;107:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper MA, Fehniger TA, Turner SC, et al. Human natural killer cells: a unique innate immunoregulatory role for the CD56 (bright) subset. Blood. 2001;97:3146–51. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayakawa Y, Smyth MJ. CD27 dissects mature NK cells into two subsets with distinct responsiveness and migratory capacity. J Immunol. 2006;176:1517–24. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lantz O, Bendelac A. An invariant T cell receptor alpha chain is used by a unique subset of major histocompatibility complex class I-specific CD4+ and CD4-8- T cells in mice and humans. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1097–106. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linsen L, Somers V, Stinissen P. Immunoregulation of autoimmunity by natural killer T cells. Hum Immunol. 2005;66:1193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2006.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albarran B, Goncalves L, Salmen S, et al. Profiles of NK, NKT cell activation and cytokine production following vaccination against hepatitis B. APMIS. 2005;113:526–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2005.apm_191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kinjo Y, Tupin E, Wu D, et al. Natural killer T cells recognize diacylglycerol antigens from pathogenic bacteria. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:978–86. doi: 10.1038/ni1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawakami K, Kinjo Y, Uezu K, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1-dependent increase of V alpha 14 NK T cells in lungs and their roles in Th1 response and host defense in cryptococcal infection. J Immunol. 2001;167:6525–32. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korten S, Anderson RJ, Hannan CM, et al. Invariant Valpha14 chain NKT cells promote Plasmodium berghei circumsporozoite protein-specific gamma interferon- and tumor necrosis factor alpha-producing CD8+ T cells in the liver after poxvirus vaccination of mice. Infect Immun. 2005;73:849–58. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.2.849-858.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawano T, Nakayama T, Kamada N, et al. Antitumor cytotoxicity mediated by ligand-activated human V alpha24 NKT cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5102–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morita CT, Li H, Lamphear JG, et al. Superantigen recognition by gammadelta T cells: SEA recognition site for human Vgamma2 T cell receptors. Immunity. 2001;14:331–44. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haas W, Pereira P, Tonegawa S. Gamma/delta cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:637–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.003225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bukowski JF, Morita CT, Brenner MB. Human gamma delta T cells recognize alkylamines derived from microbes, edible plants, and tea: implications for innate immunity. Immunity. 1999;11:57–65. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferrarini M, Ferrero E, Dagna L, Poggi A, Zocchi MR. Human gammadelta T cells: a nonredundant system in the immune-surveillance against cancer. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:14–18. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02110-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Born WK, Reardon CL, O'Brien RL. The function of gammadelta T cells in innate immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:31–8. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stewart CA, Walzer T, Robbins SH, Malissen B, Vivier E, Prinz I. Germ-line and rearranged Tcrd transcription distinguish bona fide NK cells and NK-like gammadelta T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1442–52. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crowe NY, Uldrich AP, Kyparissoudis K, et al. Glycolipid antigen drives rapid expansion and sustained cytokine production by NK T cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:4020–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.4020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Santiago-Schwarz F, Anand P, Liu S, Carsons SE. Dendritic cells (DCs) in rheumatoid arthritis (RA): progenitor cells and soluble factors contained in RA synovial fluid yield a subset of myeloid DCs that preferentially activate Th1 inflammatory-type responses. J Immunol. 2001;167:1758–68. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang AL, Colmenero P, Purath U, et al. Natural killer cells trigger differentiation of monocytes into dendritic cells. Blood. 2007;110:2484–93. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-076364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hansson M, Petersson M, Koo GC, Wigzell H, Kiessling R. In vivo function of natural killer cells as regulators of myeloid precursor cells in the spleen. Eur J Immunol. 1988;18:485–8. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830180326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trinchieri G. Natural killer cells wear different hats: effector cells of innate resistance and regulatory cells of adaptive immunity and of hematopoiesis. Semin Immunol. 1995;7:83–8. doi: 10.1006/smim.1995.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pisa P, Sitnicka E, Hansson M. Activated natural killer cells suppress myelopoiesis in mice with severe combined immunodeficiency. Scand J Immunol. 1993;37:529–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1993.tb03330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pistoia V, Zupo S, Corcione A, et al. Production of colony-stimulating activity by human natural killer cells: analysis of the conditions that influence the release and detection of colony-stimulating activity. Blood. 1989;74:156–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferlazzo G, Tsang ML, Moretta L, Melioli G, Steinman RM, Munz C. Human dendritic cells activate resting natural killer (NK) cells and are recognized via the NKp30 receptor by activated NK cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:343–51. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gerosa F, Baldani-Guerra B, Nisii C, Marchesini V, Carra G, Trinchieri G. Reciprocal activating interaction between natural killer cells and dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:327–33. doi: 10.1084/jem.20010938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Piccioli D, Sbrana S, Melandri E, Valiante NM. Contact-dependent stimulation and inhibition of dendritic cells by natural killer cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:335–41. doi: 10.1084/jem.20010934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tosi D, Valenti R, Cova A, et al. Role of cross-talk between IFN-alpha-induced monocyte-derived dendritic cells and NK cells in priming CD8+ T cell responses against human tumor antigens. J Immunol. 2004;172:5363–70. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Della CM, Romagnani C, Thiel A, Moretta L, Moretta A. Multidirectional interactions are bridging human NK cells with plasmacytoid and monocyte-derived dendritic cells during innate immune responses. Blood. 2006;108:3851–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-004028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Munz C, Dao T, Ferlazzo G, de Cos MA, Goodman K, Young JW. Mature myeloid dendritic cell subsets have distinct roles for activation and viability of circulating human natural killer cells. Blood. 2005;105:266–73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gerosa F, Gobbi A, Zorzi P, et al. The reciprocal interaction of NK cells with plasmacytoid or myeloid dendritic cells profoundly affects innate resistance functions. J Immunol. 2005;174:727–34. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Romagnani C, Della CM, Kohler S, et al. Activation of human NK cells by plasmacytoid dendritic cells and its modulation by CD4+ T helper cells and CD4+ CD25hi T regulatory cells. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:2452–8. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Borg C, Jalil A, Laderach D, et al. NK cell activation by dendritic cells (DCs) requires the formation of a synapse leading to IL-12 polarization in DCs. Blood. 2004;104:3267–75. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koka R, Burkett P, Chien M, Chai S, Boone DL, Ma A. Cutting edge: murine dendritic cells require IL-15R alpha to prime NK cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:3594–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barr DP, Belz GT, Reading PC, et al. A role for plasmacytoid dendritic cells in the rapid IL-18-dependent activation of NK cells following HSV-1 infection. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1334–42. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Granucci F, Zanoni I, Pavelka N, et al. A contribution of mouse dendritic cell-derived IL-2 for NK cell activation. J Exp Med. 2004;200:287–95. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lucas M, Schachterle W, Oberle K, Aichele P, Diefenbach A. Dendritic cells prime natural killer cells by trans-presenting interleukin 15. Immunity. 2007;26:503–17. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vitale M, Della CM, Carlomagno S, et al. NK-dependent DC maturation is mediated by TNFalpha and IFNgamma released upon engagement of the NKp30 triggering receptor. Blood. 2005;106:566–71. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-4035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kitamura H, Iwakabe K, Yahata T, et al. The natural killer T (NKT) cell ligand alpha-galactosylceramide demonstrates its immunopotentiating effect by inducing interleukin (IL)-12 production by dendritic cells and IL-12 receptor expression on NKT cells. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1121–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.7.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fujii S, Liu K, Smith C, Bonito AJ, Steinman RM. The linkage of innate to adaptive immunity via maturing dendritic cells in vivo requires CD40 ligation in addition to antigen presentation and CD80/86 costimulation. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1607–18. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brigl M, Bry L, Kent SC, Gumperz JE, Brenner MB. Mechanism of CD1d-restricted natural killer T cell activation during microbial infection. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1230–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mattner J, Debord KL, Ismail N, et al. Exogenous and endogenous glycolipid antigens activate NKT cells during microbial infections. Nature. 2005;434:525–9. doi: 10.1038/nature03408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hermans IF, Silk JD, Gileadi U, et al. NKT cells enhance CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses to soluble antigen in vivo through direct interaction with dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:5140–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Silk JD, Hermans IF, Gileadi U, et al. Utilizing the adjuvant properties of CD1d-dependent NK T cells in T cell-mediated immunotherapy. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1800–11. doi: 10.1172/JCI22046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marschner A, Rothenfusser S, Hornung V, et al. CpG ODN enhance antigen-specific NKT cell activation via plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:2347–57. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Conti L, Casetti R, Cardone M, et al. Reciprocal activating interaction between dendritic cells and pamidronate-stimulated gammadelta T cells: role of CD86 and inflammatory cytokines. J Immunol. 2005;174:252–60. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Leslie DS, Vincent MS, Spada FM, et al. CD1-mediated gamma/delta T cell maturation of dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1575–84. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shrestha N, Ida JA, Lubinski AS, Pallin M, Kaplan G, Haslett PA. Regulation of acquired immunity by gamma delta T-cell/dendritic–cell interactions. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005;1062:79–94. doi: 10.1196/annals.1358.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ismaili J, Olislagers V, Poupot R, Fournie JJ, Goldman M. Human gamma delta T cells induce dendritic cell maturation. Clin Immunol. 2002;103:296–302. doi: 10.1006/clim.2002.5218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Granelli-Piperno A, Golebiowska A, Trumpfheller C, Siegal FP, Steinman RM. HIV-1-infected monocyte-derived dendritic cells do not undergo maturation but can elicit IL-10 production and T cell regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:7669–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402431101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ferlazzo G, Pack M, Thomas D, et al. Distinct roles of IL-12 and IL-15 in human natural killer cell activation by dendritic cells from secondary lymphoid organs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16606–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407522101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Martin-Fontecha A, Thomsen LL, Brett S, et al. Induced recruitment of NK cells to lymph nodes provides IFN-gamma for T (H) 1 priming. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1260–5. doi: 10.1038/ni1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mocikat R, Braumuller H, Gumy A, et al. Natural killer cells activated by MHC class I (low) targets prime dendritic cells to induce protective CD8 T cell responses. Immunity. 2003;19:561–9. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00264-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Adam C, King S, Allgeier T, et al. DC–NK cell cross talk as a novel CD4+ T-cell-independent pathway for antitumor CTL induction. Blood. 2005;106:338–44. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Guan H, Moretto M, Bzik DJ, Gigley J, Khan IA. NK cells enhance dendritic cell response against parasite antigens via NKG2D pathway. J Immunol. 2007;179:590–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Josien R, Heslan M, Soulillou JP, Cuturi MC. Rat spleen dendritic cells express natural killer cell receptor protein 1 (NKR-P1) and have cytotoxic activity to select targets via a Ca2+-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med. 1997;186:467–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.3.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vanderheyde N, Aksoy E, Amraoui Z, Vandenabeele P, Goldman M, Willems F. Tumoricidal activity of monocyte-derived dendritic cells: evidence for a caspase-8-dependent, Fas-associated death domain-independent mechanism. J Immunol. 2001;167:3565–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.7.3565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vidalain PO, Azocar O, Lamouille B, Astier A, Rabourdin-Combe C, Servet-Delprat C. Measles virus induces functional TRAIL production by human dendritic cells. J Virol. 2000;74:556–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.556-559.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hubert P, Giannini SL, Vanderplasschen A, et al. Dendritic cells induce the death of human papillomavirus-transformed keratinocytes. FASEB J. 2001;15:2521–3. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0872fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vanderheyde N, Vandenabeele P, Goldman M, Willems F. Distinct mechanisms are involved in tumoristatic and tumoricidal activities of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Immunol Lett. 2004;91:99–101. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Trinite B, Chauvin C, Peche H, Voisine C, Heslan M, Josien R. Immature CD4- CD103+ rat dendritic cells induce rapid caspase-independent apoptosis-like cell death in various tumor and nontumor cells and phagocytose their victims. J Immunol. 2005;175:2408–17. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Taieb J, Chaput N, Menard C, et al. A novel dendritic cell subset involved in tumor immunosurveillance. Nat Med. 2006;12:214–19. doi: 10.1038/nm1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chan CW, Crafton E, Fan HN, et al. Interferon-producing killer dendritic cells provide a link between innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Med. 2006;12:207–13. doi: 10.1038/nm1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Blasius AL, Barchet W, Cella M, Colonna M. Development and function of murine B220+CD11c+NK1.1+ cells identify them as a subset of NK cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2561–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Caminschi I, Ahmet F, Heger K, et al. Putative IKDCs are functionally and developmentally similar to natural killer cells, but not to dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2579–90. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vosshenrich CA, Lesjean-Pottier S, Hasan M, et al. CD11cloB220+ interferon-producing killer dendritic cells are activated natural killer cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2569–78. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cavanaugh VJ, Deng Y, Birkenbach MP, Slater JS, Campbell AE. Vigorous innate and virus-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses to murine cytomegalovirus in the submaxillary salivary gland. J Virol. 2003;77:1703–17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.3.1703-1717.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Homann D, Jahreis A, Wolfe T, et al. CD40L blockade prevents autoimmune diabetes by induction of bitypic NK/DC regulatory cells. Immunity. 2002;16:403–15. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00290-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hanna J, Gonen-Gross T, Fitchett J, et al. Novel APC-like properties of human NK cells directly regulate T cell activation. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1612–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI22787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 90.Moser B, Brandes M. Gammadelta T cells: an alternative type of professional APC. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:112–18. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Brandes M, Willimann K, Moser B. Professional antigen-presentation function by human gammadelta T Cells. Science. 2005;309:264–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1110267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Celestin J, Rotschke O, Falk K, et al. IL-3 induces B7.2 (CD86) expression and costimulatory activity in human eosinophils. J Immunol. 2001;167:6097–104. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brandes M, Willimann K, Lang AB, et al. Flexible migration program regulates gamma delta T-cell involvement in humoral immunity. Blood. 2003;102:3693–701. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Moretta A, Marcenaro E, Sivori S, Della CM, Vitale M, Moretta L. Early liaisons between cells of the innate immune system in inflamed peripheral tissues. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:668–75. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ferlazzo G, Morandi B, D'Agostino A, et al. The interaction between NK cells and dendritic cells in bacterial infections results in rapid induction of NK cell activation and in the lysis of uninfected dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:306–13. doi: 10.1002/immu.200310004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Della CM, Vitale M, Carlomagno S, Ferlazzo G, Moretta L, Moretta A. The natural killer cell-mediated killing of autologous dendritic cells is confined to a cell subset expressing CD94/NKG2A, but lacking inhibitory killer Ig-like receptors. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:1657–66. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hayakawa Y, Screpanti V, Yagita H, et al. NK cell TRAIL eliminates immature dendritic cells in vivo and limits dendritic cell vaccination efficacy. J Immunol. 2004;172:123–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pietra G, Romagnani C, Mazzarino P, Millo E, Moretta L, Mingari MC. Comparative analysis of NK- or NK-CTL-mediated lysis of immature or mature autologous dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:3427–32. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Campos-Martin Y, Colmenares M, Gozalbo-Lopez B, Lopez-Nunez M, Savage PB, Martinez-Naves E. Immature human dendritic cells infected with Leishmania infantum are resistant to NK-mediated cytolysis but are efficiently recognized by NKT cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:6172–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.6172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]