Abstract

Objectives

Implement a Pharmacy Faculty Academy designed to foster professional growth of new faculty members in an outcomes-oriented, “frames”-based manner and to evaluate the impact on faculty satisfaction and retention rates.

Design

A Faculty Academy was designed based on critical themes relevant to junior faculty members and important symbolic, structural, human resource, and political considerations. The year-long program included concentrated sessions during the first 4 weeks of employment followed by longitudinal activities requiring an advancing level of faculty performance.

Assessment

Qualitative and quantitative metrics for engagement and professional growth improved dramatically during the implementation period. The 21 faculty members who completed the program from 2005-2007 provided positive feedback.

Conclusion

An individualized, systematic approach to faculty development resulted in more highly engaged and productive faculty members who were more likely to remain long term within the College.

Keywords: professional growth, faculty development, faculty, orientation, faculty academy

INTRODUCTION

The American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) Committee on Academic Affairs summarized critical internal and external factors influencing the integrity and direction of pharmaceutical education. This environmental scan advanced previous work suggesting the academy maintain a “dynamic curriculum congruent with the needs of society.”1 The most influential factor was the release of modifications to the pharmacy professional degree standards (Standards 2007) by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE).2 Standards 2007 emphasized the “development of students who can contribute to the care of patients and to the profession by practicing with competence and confidence.” It further reinforced the recommendations of the Institute of Medicine that pharmacists, like all health professionals, be prepared to “deliver patient-centered care as members of an inter-professional team, emphasizing evidence-based practice, quality improvement approaches, and informatics.”2

Standards 2007 emphasizes the need for pharmacy students to receive more exposure to quality experiential opportunities across multiple pharmacy practice settings. This creates a challenge for experiential programs as the availability of preceptors and faculty members diminish. In fact, the academy is in urgent need of sustainable, effective models for mentoring and fostering the growth of junior faculty and preceptors.3 Approximately 3 pharmacy practice members per department resign annually.4 Pharmacy practice faculty members represent the largest segment of academia and almost half of pharmacy practice faculty members are assistant professors with less than 5 years of academic experience.5 Faculty and pharmacist shortages, increasing workloads, poor communication with administrators, and salary differentials can create situations leading to faculty burnout and eventual departure. In order to successfully transform and maintain quality curricula, the academy must proactively engage the faculty workforce so they are prepared to guide the next generation of direct-patient-care practitioners.3

Growth in new schools of pharmacy and expansion of existing programs in the context of decreased faculty resources may jeopardize the future enterprise of pharmacy education. Solutions to effectively recruit, mentor, and retain junior faculty members are complicated by the sheer numbers of new faculty members hired annually compared to the number of senior faculty members who assist with development and mentoring activities. Given the desire to positively influence measures of performance, faculty morale, satisfaction, and overall engagement within St. Louis College of Pharmacy, a strategic framework was created to address junior faculty development in an outcomes-based, comprehensive manner, while maximizing existing faculty time and resources.

DESIGN

The St. Louis College of Pharmacy desired to create a systematic framework linked with outcomes to guide quality improvement and faculty success. The format of a Faculty Academy was chosen as a means of connecting diverse activities, workshops, simulations, reflections, and social interactions in an organized fashion. The following principles guided the design of the program: (1) reinforce mission, vision, and core values as often as possible to create a community of pharmacy faculty with shared understandings; (2) drive quality improvement through timely assessments and evaluations measuring progress; (3) model processes or “best practices” requiring participants to perform at increasingly higher levels as they progress through the Faculty Academy; and (4) foster organizational commitment for the faculty development initiatives.

Methodology for Faculty Academy Design

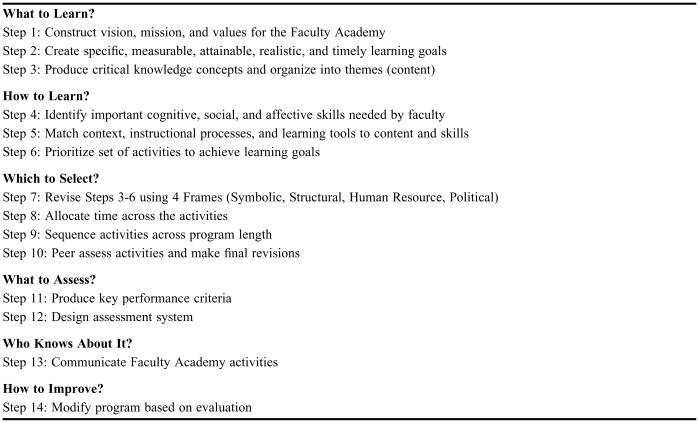

In order to systematically design a sensible program for new faculty members, it was important to clearly define the complex series of steps fostering program development and implementation. In this methodology (Table 1), the authors expanded the concept of “reframing” to ensure success of the program. This framework helped the designers to uncover potential obstacles and to organize the complex steps in logical, effective sequences.6-7

Table 1.

Methodology for Faculty Academy

To begin, the authors set the scope of the program by articulating the starting and ending points for the initial phase of the Faculty Academy. The assumption was made that new faculty members would begin the program with minimal knowledge of teaching and learning principles. Therefore, more emphasis was placed on the themes described in Table 2 and at a more basic level. Within each theme, decisions were made to define the level of performance expected to be achieved at the completion of the program. These outcomes served as a compass to ensure the consistency of performance expectations while keeping in mind that the audience was junior faculty members. A decision was made to provide more emphasis on teaching and learning while maintaining a balance with other dimensions such as service and scholarship themes.

Table 2.

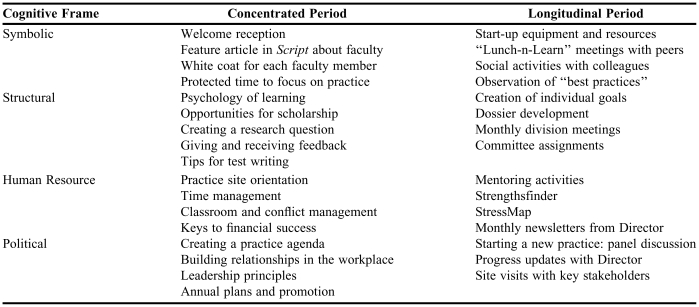

Examples of Frame-Based Activities

Once the scope of the program was defined, the authors critically evaluated faculty development needs utilizing the cognitive lenses.7 By doing this, an inventory of key issues was identified within each frame. It was important not only to consider cognitive components such as key content areas to include within workshops, eg, the psychology of learning, but to also think about social and affective qualities as well. Therefore, new faculty members were put into situations where they had to demonstrate abilities such as interacting with students, giving feedback, and professionalism. Next, the authors merged the inventories together to consider contexts in which the critical issues should be delivered or “practiced” by new faculty members. For example, decisions were made to have faculty members not only read articles about classroom active-learning techniques but also observe senior faculty members demonstrating techniques in a classroom, with new faculty members providing an assessment and self-reflection. This was followed by a team of new faculty members leading a book club such as How Full is Your Bucket?, in which they designed the active-learning techniques and delivered the program for an audience of peers. The emphasis was placed on processes that model and reinforce “best practices” of teaching and learning while fostering a greater understanding of core values and expectations within the College.

Once the key elements were placed into specific context and grouped into logical activities, the next challenging step was sequencing the order. To help create more focus, criteria were designed for each phase of the academy to ensure that each set of activities allowed faculty members to build upon the previously practiced abilities, ensuring their growth as they progressed through the academy. The foundation period was the first 4 weeks of employment. The longitudinal period was the next 3 months in which the faculty members were primarily observing, practicing, and receiving feedback on various activities. The performance period was the next 6 months in which each member was actively performing key activities such as taking his/her first student on an advanced practice experience. Within each stage, criteria facilitated both organization of product and processes so that faculty members experienced “just in time” learning.

For each series of steps, feedback mechanisms were important as a means for assessment and evaluation. Not only did faculty members have opportunities to complete self-assessments and receive peer feedback, but the data gathered provided feedback to the academy designers regarding ways to improve the program. A method of identifying strengths, areas for improvements, and insights was incorporated into the program to provide feedback for improvements. As a faculty member moved from one stage to the next, information and resources were made available to assist with development.

“Frames” as a Quality Enhancement Tool

A key element of the methodology used was the incorporation of frames as a method to enhance the quality of the program. Reframing is based on the work of Bolman and Deal who introduced the concept within their book Reframing Organizations: Artistry, Choice, and Leadership.7 The authors describe cognitive lenses that help leaders look at complex and deceptive and perhaps surprising aspects of organizations through 4 perspectives or “frames” to help find clarity and meaning that can lead to good decision making. The symbolic frame guides one to think about symbols that carry powerful emotional messages that create the culture within the organization. The structural frame allows one to focus more on the organizational structure, policies and procedures, or perhaps committee structures that help to form goals and outcomes. The human resource frame allows one to focus more on the individuals within the organization in order to recognize and reward talent, seek ways to enhance development, or empower individuals. Finally, the political frame provides more focus on methods for managing conflict, identifying stakeholders, mapping the political terrain, bargaining and negotiating to set agendas.

Symbolic Frame

Symbols are often used to reinforce the culture within an organization. Symbols can be simple activities, like meetings or social events, or more significant events like merit raises, graduation ceremonies, or white coat presentations. Also, symbols can be the collective “way of being” within an organization, such as furnishings, photographs placed on desks, or the clothing worn within the organization. Together, these symbols create images of meaning that share information with others regarding “the way we do things.” Hopefully, they reinforce positive, constructive images of the institution. When symbols are genuine they can stimulate the mind's eye, touch the heart, or rally support during stressful times. When they are superficial or inauthentic, colleagues may see them as a waste of time or sustaining a hidden agenda. Therefore, good intentions can be interpreted in the wrong way. For example, faculty evaluations could be considered as a positive activity to reinforce individual strengths, recognize good work, and reward excellence. However, if they are conducted in ways perceived as subjective, disorganized, or demoralizing, then the outcome is destructive.7

The first step of planning was to create an inventory of the symbols within the College to decide if they sent the intended message and then decide upon components that should be reinforced within the Faculty Academy. Table 2 summarizes examples of symbolic items that were incorporated into the program. The inventory was updated annually to evaluate whether modifications were needed. It is important to tailor the Faculty Academy to the mission and vision of the institution. The vision of St. Louis College of Pharmacy was to be the benchmark learning-and-growth-centered college of pharmacy. Therefore, the symbols would be more reflective of this emphasis on excellence in teaching and learning. The vision of the Division of Pharmacy Practice's was to be recognized as a leader in academic clinical pharmacy. The Divisions' mission was to make a meaningful difference in student learning, patient care, and pharmacy education. To achieve this end we were committed to (1) developing an assessment-driven curriculum that provides students with the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes to succeed in the future; (2) supporting role-model faculty practitioners who impact on patient outcomes and achieve high levels of credibility with other members of the health care team; (3) creating opportunities for all faculty members to engage in purposeful research and scholarship that address questions related to pharmacotherapy, education, or patient care; and (4) achieving effective collegial and mentoring relationships with students, trainees, and faculty peers.

Structural Frame

Organizations use structures such as committees, policies, and procedures to create expectations, define lines of communication and authority, and establish goals for achieving defined outcomes.7 Therefore, significant time should be allocated to foster the understanding of the structure within the college. By reviewing the organizational structure of the college and general duties of key administrators, the faculty develops a better understanding of their major responsibilities in case questions arise or assistance is needed. The strategic plans provide concepts about goals and direction for the future which give faculty members a sense of “the College's” expectations as they prepare individualized goals for their immediate future. Some of the most important items were those “just in time” that help address immediate questions or concerns for new faculty members, such as the process for determining topics to teach, expectations for students completing advanced practice experiences, indicators regarding good performance, and calendar of upcoming events.

The content for the academy was guided by the 10 principles of “good practice” created by Chickering and Gamson: communicates expectations for performance; (2) gives feedback on progress; (3) enhances collegial review processes; (4) creates flexible timelines for tenure; (5) encourages mentoring by senior faculty; (6) extends mentoring and feedback to graduate students who aspire to be faculty members; (7) recognizes the department chair as a career sponsor; (8) supports teaching; (9) supports scholarly development; (10) fosters a balance between professional and personal life.8

In addition, Wilkerson and colleagues proposed that a comprehensive development program should include promotion of individual scholarship and overall academic success (professional) and opportunities for faculty members to enhance teaching abilities (instruction); become change agents within the organization (leadership); and influence the culture of the institution (organizational).9 MacKinnon provided further information on topics and delivery options that are most desirable during a faculty member's first year.10 These items included developing instruction methods, grant writing skills, using technology, managing personal time, and understanding the promotion and tenure processes. The most preferred method of delivery consisted of live seminars followed by computer-assisted instruction. Table 2 describes structural examples of the critical themes incorporated into the Faculty Academy as well as activities that provided faculty members chances to be actively engaged. In addition, the activities provided faculty members with exposure to “best practices” for teaching and learning and all activities were designed to progressively build on each other so that faculty members would be challenged to reach higher levels of performance.

From the structural perspective, the goal of the academy was to create a clear picture of the structure of the College. In order to model this aspect, attempts were made to ensure that the academy was well organized. First, a survey was conducted to determine the most important information that new faculty members needed as they began an academic career. Artifacts incorporated into the academy were distributed in a binder or hardcopy format and via the online course management program, WebCT. This online system was specifically used so faculty members could become familiar with the technology from a student perspective. In addition, an Intranet site was available to faculty members called, “myStLCoP” which allowed access to policies, forms, committees, and Internet links from a single Internet location.

Besides providing key documents and artifacts for faculty members, another major step of the academy development was deciding on the concepts, processes, and contexts to use for faculty learning. Phase one of the academy was a 4-week program coinciding with the first day of employment. This allowed emphasis to be placed on general campus and clinical site orientations and the basics for student teaching and learning. During this time, faculty members spent each morning at their assigned clinical site conducting orientation activities followed by campus programming in the afternoons. Since our mission was to provide excellence in teaching and learning, a majority of our content emphasized this theme. At the conclusion of phase one, the faculty began a longitudinal aspect that was more individualized to best meet their development needs. Finally, the academy was meant to engage faculty members in various activities so they could “practice” in a controlled environment and to provide them with opportunities for self-reflection and peer feedback. Therefore, the concepts were often delivered via structured homework, online presentations, readings, or live seminars. This was typically followed by opportunities to “do” or practice these abilities. The following summarizes some of the practice opportunities embedded within the academy: providing feedback to residents, preparing teaching and learning materials such as cases or test questions, assessing self or others and discussing how to improve assessment abilities, leading book clubs for the division that allowed them to incorporate the teaching techniques learned, observing facilitation sessions, planning syllabi and sharing feedback with mentors, making site visits to observe how other faculty members have created learning environments in clinical practice, and creating learning activities using technology.

Human Resource Frame

One of the greatest resources within a college of pharmacy is its people. Each person is uniquely talented to advance the mission of the college. Bolman and Deal indicate the importance of a “good fit” between employees and the organization. For example, faculty members seek activities that are meaningful and will ultimately bring happiness and pride. College of pharmacy seek “the best and brightest” individuals who have good ideas and abilities to achieve organizational goals. Therefore, it is a symbiotic relationship that should be nurtured. It is critical to consider the way in which we reward and recognize quality work while fostering individual growth as academicians.7

Based on the human resource frame, activities should be designed that place emphasis on methods to recognize and reward excellence, build powerful relationships, encourage empowerment, and provide opportunities to continuously develop strengths. Activities should be planned to allow new faculty members to socially interact with each other as well as other faculty or staff members in order to foster trusting relationships. In addition, time should be set aside to clearly describe the expectations of new faculty members and how they relate to the expectations of other faculty members. Often, individuals want to make sure they are “pulling their fair share” of the workload and contributing to the overall functioning of the college. Mentors assist new faculty members with developing an individualized development plan and offering tips for success. Finally, the reporting supervisor should consider methods for recognizing the successes of new faculty members and routinely meet with new faculty members to discuss progress.

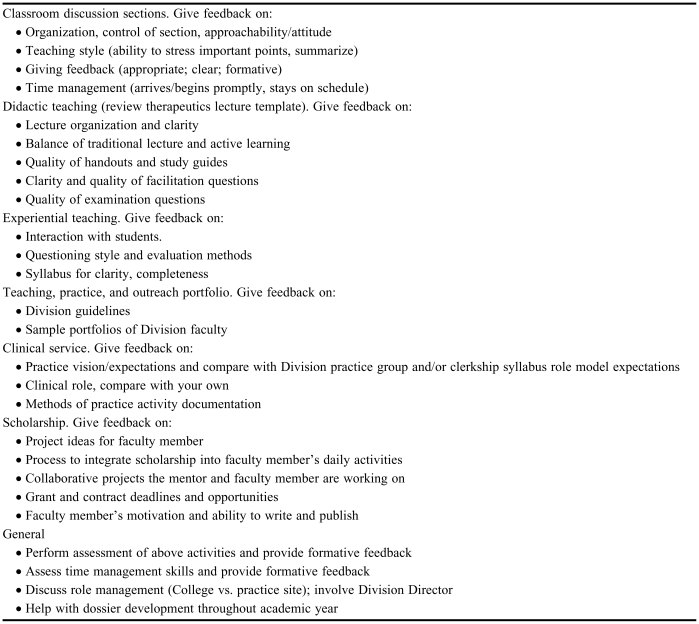

Table 2 summarizes examples of the activities incorporated into the Academy based on this analysis of human resource needs within our College. Table 3 provides an excerpt of mentoring activities incorporated into the Faculty Academy that ran longitudinally during the first year. Each new faculty member was assigned to a senior mentor to assist with transition into the College. Individuals were paired based on shared areas of interest, previous professional background, teaching responsibilities, and personality. The assignments were made by the Division Director following conversations with each new faculty member.

Table 3.

Mentoring Activities Incorporated into Faculty Academy

Political Frame

The political frame emphasizes building supportive teams, dealing with conflicts, and advancing agendas. This frame provides insight for new faculty as they create pharmacy services within new practice sites. Bolman and Deal emphasizes that organizations are typically filled with individuals with varying backgrounds, opinions, and interests. These coalitions help shape the values and agendas of colleges of pharmacy and are influential in determining the allocation of scare resources. Therefore, it is imperative that faculty members develop skills such as bargaining, negotiation, and positioning oneself among competing stakeholders.7

Given these assumptions, new faculty members must develop the abilities to mobilize individuals in a fashion to accomplish important objectives despite obstacles and external forces. Bolman and Deal describe these key skills as “agenda setting, mapping the political terrain, networking and forming coalitions, and bargaining and negotiating.” Therefore emphasis is placed on activities that help new faculty members create agendas for implementing a clinical practice that will effectively support the experiential education of students and provide a model for innovative patient care. These activities guide new faculty members to think about the needs of the providers, the patient population, and the pharmacy services that best serve them, and balancing these aspects with the strengths and expertise of the faculty member. This needs assessment allows the faculty member the opportunity to set measurable goals, a statement of direction, and a strategy to move with focus toward implementation. Activities to help faculty members with this aspect are included in Table 2.

Faculty mentors and the department chairs play an important role in familiarizing new faculty members with the political terrain and identifying key stakeholders within the organization. Communication is also important and mentors can help new faculty members determine essential channels of communication while uncovering potential “landmines” or challenges. It is essential that supervisors adequately prepare a practice site in advance for the new faculty member. This helps to create a shared understanding of the role of the individual and eases the faculty member's transition into the new environment. The department chair is an integral person in helping the new faculty member form a coalition of support for new services and activities.11 The chair serves as the “cheerleader” and prevents new faculty members from getting caught in the middle of a tug-of-war between practice site wishes and college needs. Finally, junior faculty members need guidance regarding methods for bargaining and negotiating for resources, privileges, and promotions so that mutual gain can be achieved while holding to a standard of fairness.

Engagement

The Faculty Academy involved the entire division of pharmacy practice. Therefore, a measure was sought to determine the influence of the program in overall division performance and culture. The engagement of faculty members within the department was measured by the Gallup Q index.12 The Gallup University interviewed over 1 million employees worldwide across more than 2500 business, healthcare, and educational organizations. Analysis of employee attitude responses isolated specific dimensions that differentiate very successful units from less successful ones. Their research produced a set of 12 items that measured employee “engagement.” Engagement is the description of positive employee perceptions that best predicts retention of employees, overall organization productivity, satisfaction, and profitability of an organization. Validity was established by comparing top-performing organizations and poor performers to analyze the engagement index corresponding to the resulting workplace outcomes. Changes in the engagement index of at least 0.2 units resulted in significant workplace outcomes.

ASSESSMENT

Twenty-one individuals participated in the St Louis College of Pharmacy's Faculty Academy from 2005-2007. Faculty engagement improved from a baseline score of 3.37 in 2004, which was below the national benchmark Gallup 50th percentile (3.72). By 2007, the College's engagement score rose to 3.91, approaching the Gallup 75th percentile (4.0). The most dramatic rise was observed in items related to employee recognition and praise (+1.4) and encouragement of personal development (+0.83). While no areas declined, the least dramatic improvement was observed in the dimension measuring perceptions of colleague commitment to quality work, which faculty members had rated high at baseline. The improvement in organizational engagement reflected an improvement in retention rates. For example, the College's attrition rate improved from a 5-year average of 25% (2000-2004) to 6% (2005-2007).

During the Academy, faculty participants were asked to provide feedback regarding the quality of the programming. Overall, the assessments were positive and provided direction for continued improvements. Feedback such as “the academy recognized we were humans, not robots. It was great to hear that we should block off time to focus on personal development like hobbies and not just do work. It was nice they encouraged us to block off time for personal activities to create balance” and “peer assessment of lectures and slides prior to presenting them for a class is very informative and really accelerated the mentoring process” allowed us to build upon the strengths of the Faculty Academy. Feedback such as “midway through the first year it would be nice to have some focus sessions on ‘balancing’ scholarship with teaching and how to make sure we have protected time to develop scholarship” provided suggestions for improving the program.

The professional growth of faculty participants was measured by various metrics illustrating productivity changes. The average publication per faculty member per year increased from 0.72 (2004) to 1.46 (2007). The number of abstracts, case reports, or monographs per faculty member per year increased from 0.52 (2004) to 1.53 (2007). The number of invited national lectures, papers, and posters increased from 1.1 (2004) to 1.78 (2007). The percentage of pharmacy practice faculty members with the credential of board certification increased from 62% (2004) to 81% (2007). The overall composite rating of individual teaching performance improved from a mean score of 3.95 (2004) to 4.48 (2007), using a scale of 0.0 (lowest performance) to 5.0 (highest performance). Finally, 4 faculty members were successfully promoted to the rank of associate professor and 16 assistant professors received positive third-year promotion and tenure reviews by peers reviewing dossiers and performance portfolios.

St. Louis College of Pharmacy demonstrated commitment to professional growth by providing resources for faculty development activities embedded within the Faculty Academy. Overall, the pharmacy practice operational budget grew with approximately a 90% increase in faculty development funds, along with the creation of new budget lines for faculty retention and professional development exceeding $10,000 to support the Faculty Academy program.

DISCUSSION

An AACP taskforce identified the need for members of the academy to develop, implement, and share model programs and “best practices” so that more programs could be implemented in the future.3 This paper describes a methodology for designing a comprehensive, sustainable faculty development program, the Faculty Academy. It demonstrates that a College of Pharmacy can effectively incorporate evidence-based strategies using a reframing analysis to help balance the various internal and external factors most likely to influence faculty recruitment, retention, and engagement.

Colleges of pharmacy can do much more to address the needs of faculty members in a formal, comprehensive manner. Based on the AACP Task Force on Faculty Workforce projection that the number of vacant faculty positions could surpass 1200 by the year 2017, the committee wrote “hindsight being what it is, it is safe to say that the academy would be in a different place today, if it would have been more responsive to earlier warnings.”3 MacKinnon collected data from a random sample of 600 faculty members to determine the attitudes and experiences of pharmacy educators toward faculty development programs. Approximately 25% indicated programs for newly hired faculty members existed within their colleges of pharmacy. The level of formal faculty development opportunities was available in less than 10% of institutions. Finally, the majority of respondents did not perceive a mentoring relationship present within their first academic appointment.10 In fact, Wutoh and colleagues found only 18% of colleges have formal mentoring program in place.13

The lack of junior faculty mentorship and development may jeopardize the integrity of future academic pharmacy programs. An AACP Task force articulated several important internal and external forces influencing faculty and academic institutions. Examples of the critical internal factors included the following: demand for faculty to meet needs of new pharmacy schools, lower salaries in academia compared to other pharmacy sectors, substantial retirement within the academy during the next 5 years, and quality of life concerns as faculty struggle to balance career and family/personal needs. Examples of critical external factors include the following: changing financial climate with more emphasis on research and grants, globalization of professional education, technology advances for delivery of education, and changes in pre-professional requirements to remediate poor high school preparation.

Along with the pressures described above, the current workforce shortage makes it challenging for colleges of pharmacy to hire qualified faculty members. A 2006 survey conducted by the AACP revealed the pharmaceutical education enterprise was supported by approximately 4300 full-time pharmacy faculty members with nearly 40% consisting of junior faculty members within pharmacy practice.5 The rise in pharmacy practice faculty members is not surprising given the increased requirements for experiential learning activities, the opening of new pharmacy schools, and the increase in existing enrollments to address pharmacy workforce shortages. In 2005, the demand for faculty members, as reported by 76 colleges and schools of pharmacy, exceeded 400, with the vast majority consisting of pharmacy practice faculty members.3 AACP has suggested colleges preferentially hire pharmacy practice faculty members with 2 years of residency training. The 2007 results of the matching process for ASHP accredited residency programs indicated that less than 200 second-year residency positions were filled for 2007.14 Therefore, it appears that the inadequate supply of practitioners with more advanced training will result in more junior faculty members requiring development and mentoring. By hiring these individuals, colleges are accepting an immense responsibility and commitment to foster continued professional development for junior faculty members within the intricate academic environment.

The strength of the Faculty Academy is the structure of the program as a system for outcome-based faculty development. Rather than simply a series of disconnected workshops, the Academy format connects learning outcomes for new faculty members across multiple dimensions, while emphasizing the foundations of both collaborative mentoring and more typical mentor-protégé models. While little is published regarding faculty academies, the concepts of building communities or teams is widely used in academia to attain levels of performance that serve as catalysts for enhanced productivity within the entire organization. Teams foster the development of trusting relationships, shared values, healthy debate of ideas, and accountability for achieving progress.15

Another strength of the Faculty Academy is the importance placed on gaining organizational commitment, creating flexibility to meet the individualized needs of the faculty member, and providing resource commitment by college leadership to support the program. Faculty members serve in so many roles. They are our clinicians, teachers, ambassadors, and scholars. Therefore, the program must be diverse to prepare new faculty members for the tripartite mission of higher education. In addition, it is critical that senior faculty members serve as mentors to help form a sense of trust and development. Through these relationships and bonds, a support system is created whereby faculty members can develop trust and camaraderie with colleagues. Because new faculty members feel bewildered about the range of things expected of them, it is helpful that the Academy created a sense of direction, goals, and integration into the College. Faculty members from across disciplines and administrators up to the President of the College participated in leading sessions of the Academy. This was an important symbolic message to everyone of the importance placed on developing new faculty members and integrating them within the organization.

An area of improvement for the Faculty Academy is to include programming beyond the initial year of employment. This is a critical time that could bridge to the promotion and tenure midpoint review which occurs at the end of their third year. This would give more time to encourage development as a scholar by collaborating on research endeavors and other scholarly projects. In addition, the program should be modified to include new hires from other disciplines. Since St. Louis College of Pharmacy is a 0-6 pharmacy program, the college is composed of liberal arts and science faculty members as well as the pharmacy faculty. A process should be created to routinely have a focus group of faculty members and practitioners conduct environmental scans of the literature to recommend additional ideas to incorporate into the Faculty Academy. Finally, other metrics should be considered as a means to monitor success of the program, such as senior faculty perceptions and teaching and learning performance, as well as measuring student learning outcomes as a result of the program.

The major insight gained through development of the Faculty Academy is the important role colleges of pharmacy have in proactively creating successful strategies for recruiting and retaining faculty members. A Faculty Academy is only one component of a college's armamentarium for achieving faculty engagement. It was important that all faculty and administrators participated in the program through attending informal discussions or leading workshops because it conveyed the College's level of commitment and sent an important message regarding the significance and value of mentoring faculty members. Recruitment strategies may consist of exposing students and residents to aspects of the academy earlier in their training, supporting residency programs, and conducting strengths-based interviewing strategies to ensure appropriate faculty members are hired to meet the challenges facing the college of pharmacy. Retention strategies may consist of salary adjustments, sabbaticals, novel benefit packages, and creative workloads to achieve balance. In concert with these initiatives, the Faculty Academy concept establishes an environment for promoting professional growth.

CONCLUSIONS

A framework for designing a Faculty Academy in a college of pharmacy was introduced. The strategy is helping the College address professional development and engagement of faculty members. Keys to successful implementation include an environmental scan to understand the internal and external forces influencing faculty engagement and using a reframing analysis to determine key aspects to incorporate into the development program. Overall, faculty members were pleased with the program as demonstrated by positive reflections, and the program has led to objective growth in metrics of engagement.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the faculty, staff, students, and administration at St Louis College of Pharmacy who participated in and helped to implement the Faculty Academy. We would like to particularly thank the Pharmacy Faculty Success Team, Ken Kirk, and Wendy Duncan-Hewitt for their leadership and advice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Report of the 2006-2007 Academic Affair Committee, American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP). Available at: http://aacp.org/. Accessed September 8, 2007.

- 2.Accreditation Standards and Guidelines for Professional Program in Pharmacy, Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE). Available at: http://www.acpe-accredit.org/standards/default.asp. Accessed August 28, 2007.

- 3.Report of the 2006-2007 Council of Faculty/Council of Deans Task Force on Faculty Workforce, American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP). Available at: http://aacp.org/. Accessed September 8, 2007.

- 4.Glover ML, Armayor GM. Expectations and orientation activities of first-year pharmacy practice faculty. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(4) Article 87. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Profile of Pharmacy Faculty, American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP). Available at: http://aacp.org. Accessed September 8, 2007.

- 6.Smith P, Apple D. Methodology for creating methodologies. In: Apple D, editor. Faculty Guidebook. Lisle, Illinois: Pacific Crest; 2006. pp. 371–4. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolman LG, Deal TE. Reframing Organizations: Artistry, Choice and Leadership. 3rd ed. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chickering AW, Gamson ZF. Applying the Seven Principles for Good Practice in Undergraduate Education. New Directions for Teaching and Learning . In: Wulff D, editor. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilkerson L, Irby DM. Strategies for improving teaching practices: a comprehensive approach to faculty development. Acad Med. 1998;73:387–96. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199804000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacKinnon GE. An investigation of pharmacy faculty attitudes toward faculty development. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(1) Article 11. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conklin MH, Desselle SP. Job turnover intentions among pharmacy faculty. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71 doi: 10.5688/aj710462. Article 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harter JK, Schmidt FL, Keyes CL. Well-being in the workplace and its relationship to business outcomes: a review of the Gallup studies. In: Keyes CL, editor. Flourishing: The Positive Person and the Good Life. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 2003. pp. 205–24. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wutoh AK, Colebrook MN, Holladay JW, et al. Faculty mentoring programs at schools/colleges of pharmacy in the U.S. J Pharm Teach. 2000;8:61–72. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pharmacy residency match-program statistics, National Matching Service. Available at: http://www.natmatch.com/ashprmp/prgstats.htm. Accessed May 7, 2007.

- 15.Grigsby RK, Kirch DG. Faculty and staff teams: a tool for unifying the academic health center and improving mission performance. Acad Med. 2006;81:688–95. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200608000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]