Abstract

Chronic systemic inflammation in the late stage of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 (HIV-1) infection could increase neuroinvasion of infected monocytes and cell-free virus, causing an aggravation of neurological disorders in AIDS patients. We previously showed that the peripheral administration of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) enhanced the uptake across the blood-brain barrier (BBB) of the HIV-1 viral protein gp120. Brain microvessel endothelial cells are targets of LPS. Here, we investigated whether the direct interaction between LPS and the BBB also affected HIV-1 transport using primary mouse brain microvessel endothelial cells (BMECs). LPS produced a dose (1–100 μg/mL)- and time (0.5–4 hr)-dependent increase in HIV-1 transport and a decrease in transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER). Whereas indomethacin (cyclooxygenase inhibitor) and L-NAME (NO synthase inhibitor) did not affect the LPS-induced changes in HIV-1 transport or TEER, pentoxifylline (TNF-αinhibitor) attenuated the decrease in TEER induced by LPS, but not the LPS-induced increase in HIV-1 transport. LPS also increased the phosphorylation of p44/42 MAPK and p38 MAPK but not that of JNK. U0126 (p44/42 MAPK inhibitor) and SP600125 (JNK inhibitor) did not inhibit the LPS-induced increase in HIV-1 transport although U0126 attenuated the reduction in TEER. SB203580 (p38 MAPK inhibitor) inhibited the LPS-induced increase in HIV-1 transport without affecting TEER. Thus, LPS-enhanced HIV-1 transport is independent of changes in TEER and so is attributed to increased transcellular trafficking of HIV-1 across the BBB. These results show that LPS increases HIV-1 transcellular transport across the BBB by a pathway that is mediated by p38 MAPK phosphorylation in BMECs.

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection of the central nervous system occurs in a majority of patients with AIDS and induces neurological dysfunctions known as AIDS-dementia complex or HIV-associated dementia (HAD). Clinical and pathological abnormalities are caused by inflammatory mediators (e.g., cytokines, chemokines, prostaglandins, and nitric oxide (NO)) secreted by brain endothelial cells (Didier et al., 2002) and HIV-infected cells in the brain, such as invading monocytes, astrocytes, and microglia (González-Scarano and Martín-García, 2005). Therefore, HIV-1 entering the brain would participate in the incidence and development of neuroAIDS syndrome. The blood-brain barrier (BBB) strictly regulates the transport of blood-borne cells and substances into the brain. Brain microvessel endothelial cells are a major component of the BBB and do not express CD4 receptor which HIV-1 uses to enter other cell types (Moses et al., 1993). Despite and absence of the CD4 receptor, HIV-1 can cross the BBB by two routes, the passage of cell free virus by adsorptive endocytosis (Banks et al., 2001) and the trafficking of infected immune cells across BBB (Persidsky et al., 1997). Both routes involve gp120, an HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein, expressed by HIV-1 infected immune cells. The binding of gp120 to brain endothelial cell surface glycoproteins induces adsorptive endocytosis (Banks et al., 1997 and 1998; Banks and Kastin, 1997). In addition to these transcellular routes, HIV-1 could use the paracellular route resulting from the disruption of tight junctions by gp120 and Tat (Kanmogne et al., 2005; András et al., 2003, 2005; Pu et al., 2005).

Although BBB disruption is associated with HAD, the degree of BBB disruption is generally minimal or mild in neuroAIDS (Power et al., 1993). HIV-1 entry through BBB disruption by the viral proteins would not be necessary for the occurrence of neurological impairment of AIDS. Indeed, at the early phase of the infection, when the BBB is fully functional, HIV-1 enters the brain (Davis et al., 1992). The basal permeability of HIV-1 for brain endothelial cells is 4.7 times greater than that of the much smaller albumin, a molecule used as a marker of BBB integrity (Nakaoke et al., 2005). This suggests that HIV-1 can cross the intact BBB. At this stage, HIV-1 would enter the brain through the transcellular route rather than the increased paracellular route disrupted by gp120 and Tat. HAD occurs after a latency of HIV-1 in CNS. This latency is a clinically relatively long stable period in which the BBB is unaffected (Nottet, 2005). Therefore, the disruption of the BBB by the viral proteins likely plays a role in the development of HAD in the late phase of AIDS.

At the late phase, HIV-1 entry becomes highly complicated because multiple factors are involved in HIV-1 entry. Probably, elevated levels of cytokines in blood and adhesion molecule expression in brain endothelial cells are involved in the development of HAD, leading to disruption of the BBB and an increase of HIV-1 and infected immune cell invasion. Chronic immune activation of HIV disease progression leads to dysregulation of macrophages, with the overproduction of various proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Gartner, 2000). Proinflammatory cytokine levels are elevated in the blood of patients with AIDS (Alonso et al., 1997; Hittinger et al., 1998). Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) enhances paracellular transport of HIV-1 across brain endothelial cells (Fiala et al., 1997) and increases endocytosis via activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling (Miller et al., 2005), which regulates HIV-1 transport (Liu et al., 2002). Both transcellular and paracellular routes for HIV-1 would be enhanced in systemic inflammatory states. Such systemic inflammation might be associated with the increase in HIV-1 entry into the brain which leads to the development of neurological impairments in HIV infection.

Our previous study showed that the peripheral administration of gram-negative bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) enhances gp120 uptake across BBB (Banks et al., 1999). This proposes two possibilities; (i) elevated levels of inflammatory mediators, including prostaglandins, NO and cytokines, in blood enhance the transport of HIV-1 across BBB or (ii) LPS directly acts on the BBB to enhance HIV-1 transport. Therefore, a systemic inflammatory or a bacterial infection could facilitate the neuroinvasion of HIV-1. Bacterial infection in HIV patients influences the severity and rate of disease progression (Blanchard et al., 1997). LPS increases the HIV-1 replication in T cells through Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling (Equils et al., 2001). The BBB is a target of LPS as are peripheral organs and immune cells. Brain endothelial cells express LPS receptors, such as TLR-2, TLR-4, and CD14 (Singh and Jiang, 2004). Several studies using in vitro BBB model showed that LPS induced an increase in BBB permeability of marker molecules (Tunkel et al., 1991; de Vries et al., 1996; Descamps et al., 2003; Boveri et al., 2006; Veszelka et al., 2007) and the release of cytokines (Verma et al., 2006), prostaglandin E2 (de Vries et al., 1995) and NO (Veszelka et al., 2007) by brain endothelial cells. We hypothesized that LPS directly acts on the BBB to facilitate HIV-1 entry across the BBB through the release of inflammatory modulators by brain endothelial cells.

Here, We used primary mouse brain microvessel endothelial cells (BMECs) to examine the ability of LPS to alter the permeability of BBB to HIV-1 and then, investigated its mechanisms in terms of inflammatory mediators released by LPS and MAPK signaling pathway.

Materials and Methods

Radioactive labeling

HIV-1 (MN) CL4/CEMX174 (T1) prepared and rendered noninfective by aldrithiol-2 treatment as previously described (Rossio et al. 1998) was a kind gift of the National Cancer Institute, NIH. The virus was radioactively labeled by the chloramine T method, a method which preserves vial coat glycoprotein activity (Frost, 1977; Montelaro and Rueckert, 1975). Two mCi of 131I-Na (Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA), 10 μg of chloramine-T (Sigma) and 5.0 μg of the virus were incubated together for 60 sec. The radioactively labeled virus was purified on a column of Sephadex G-10 (Sigma).

Primary culture of mouse brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs)

BMECs were isolated by a modified method of Szabó et al. (Szabó et al., 1997). In brief, the cerebral cortices from 8-week-old CD-1 mice were cleaned of meninges and minced. The homogenate was digested with collagenase type II (1 mg/mL; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and DNase I (30 U/mL; Sigma) in DMEM (Sigma) containing 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 50 μg/mL gentamicin and 2 mM GlutaMAX™-I (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 37°C for 40 min. Neurons and glial cells were removed by centrifugation in 20% bovine serum albumin (BSA)-DMEM (1,000 × g for 20 min). The microvessels obtained in the pellet were further digested with collagenase/dispase (1 mg/mL; Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and DNase I (30 U/mL) in DMEM at 37°C for 30 min. Microvessel endothelial cell clusters were separated by 33% Percoll (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) gradient centrifugation (1,000×g for 10 min). The obtained microvessel fragments were washed in DMEM (1,000×g for 10 min) and seeded on 60 mm culture dishes (BD FALCON™, BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) coated with 0.05 mg/mL fibronectin (Sigma), 0.05 mg/mL collagen I (Sigma) and 0.1 mg/mL collagen IV (Sigma). They were incubated in DMEM/F-12 (Sigma) supplemented with 20% plasma derived bovine serum (PDS; Quad Five, Ryegate, MT), 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 50 μg/mL gentamicin, 2 mM GlutaMAX™-I and 1 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; Sigma) at 37°C with a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air. On the next day, the BMECs migrated from the isolated capillaries and started to form a continuous monolayer. To eliminate contaminating cells (mainly pericytes), BMECs were treated with 4 μg/mL puromycin (Sigma) for the first 2 days (Perrière et al., 2005). After 2 days of the treatment, puromycin was removed from the culture medium. Culture medium was changed every other day. After 7 days in culture, BMECs typically reached 80–90% confluency.

Preparation of in vitro BBB models

BMECs (4 × 104 cells/well) were seeded on the inside of the fibronectin-collagen IV (0.1 and 0.5 mg/mL, respectively)-coated polyester membrane (0.33 cm2, 0.4 μm pore size) of a Transwell®-Clear insert (Costar, Corning, NY) placed in the well of a 24-well culture plate (Costar). Cells were cultured in DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 20% PDS, 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 50 μg/mL gentamicin, 2 mM GlutaMAX™-I, 1 ng/mL bFGF and 500 nM hydrocortisone (Sigma) at 37°C with a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air until the BMEC monolayers reached confluency (3 days). To check the integrity of the BMEC monolayers, transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER in Ω × cm2) was measured before the experiments and after an exposure of LPS using an EVOM voltohmmeter equipped with STX-2 electrode (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). The TEER of cell-free Transwell®-Clear inserts were subtracted from the obtained values.

Pretreatment protocol

Indomethacin (cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitor; Sigma), U0126 (MEK inhibitor; Tocris Cookson Inc., Ellisville, MO), SB203850 (p38 MAPK inhibitor; Tocris) and SP600125 (JNK inhibitor; Sigma) were first dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and diluted with serum-free DMEM/F-12 (0.1% as the final DMSO concentration). Lipopolysaccharide from Salmonella typhimurium (LPS; Sigma) was dissolved in serum-free DMEM/F-12 and loaded to BMEC monolayers with or without indomethacin (1 and 5 mM), NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME; NO synthase (NOS) inhibitor, Sigma) (1 and 3 mM), pentoxifylline (Phosphodiesterase inhibitor, Sigma) (0.2 and 2 mM), U0126 (5–20 μM), SB203580 (1–10 μM) and SP600125 (5–20 μM). The confluent BMEC monolayers were washed with serum-free DMEM/F-12 and then exposed to LPS (1–100 μg/mL) for 0.5–4 hr. The maximum concentration of LPS (100 μg/mL) used in these experiments was chosen based on our previous study (Verma et al., 2006).

Transendothelial transport of 131I-HIV-1

For the transport experiments, the medium was removed and BMECs were washed with physiological buffer containing 1% BSA (141 mM NaCl, 4.0 mM KCl, 2.8 mM CaCl2, 1.0 mM MgSO4, 1.0 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM D-glucose and 1% BSA, pH 7.4). The physiological buffer containing 1% BSA was added to the outside (abluminal chamber; 0.6 mL) of the Transwell® insert. To initiate the transport experiments, 131I-HIV-1 (3 × 106 cpm/mL) was loaded on the luminal chamber. The side opposite to that to which the radioactive materials were loaded is the collecting chamber. Samples were removed from the collecting chamber at 15, 30, 60 and 90 min and immediately replaced with an equal volume of fresh 1% BSA/physiological buffer. The sampling volume from the abluminal chamber was 0.5 mL. All samples were mixed with 30% trichloroacetic acid (TCA; final concentration 15%) and centrifuged at 5,400 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Radioactivity in the TCA precipitate was determined in a gamma counter. The permeability coefficient and clearance of TCA-precipitable 131I-HIV-1 was calculated according to the method described by Dehouck et al. (Dehouck et al., 1992). Clearance was expressed as microliters (μL) of radioactive tracer diffusing from the luminal to abluminal (influx) chamber and was calculated from the initial level of radioactivity in the loading chamber and final level of radioactivity in the collecting chamber: Clearance (μL) = [C]C × VC/[C]L, where [C]L is the initial radioactivity in a microliter of loading chamber (in cpm/μL), [C]C is the radioactivity in a microliter of collecting chamber (in cpm/μL), and VC is the volume of collecting chamber (in μL). During a 90-min period of the experiment, the clearance volume increased linearly with time. The volume cleared was plotted versus time, and the slope was estimated by linear regression analysis. The slope of clearance curves for the BMEC monolayer plus Transwell® membrane was denoted by PSapp, where PS is the permeability × surface area product (in μL/min). The slope of the clearance curve with a Transwell® membrane without BMECs was denoted by PSmembrane. The real PS value for the BMEC monolayer (PSe) was calculated from 1/PSapp = 1/PSmembrane + 1/PSe. The PSe values were divided by the surface area of the Transwell® inserts (0.33 cm2) to generate the endothelial permeability coefficient (Pe, in cm/min).

Cell viability

The effect of LPS on the viability of BMECs was assessed using a MTS assay (CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay, Promega, Madison, WI) (Price et al., 2006). MTS tetrazolium is reduced by mitochondrial dehydrogenase into a colored formazan product proportionally to the number of living cells. BMECs (4 × 104 cells/well) plated on 24-well collagen I/collagen IV/fibronectin-coated culture plate (Costar) were exposed to 200 μL of serum-free DMEM/F-12 containing LPS (100 μg/mL) for 4 hr. CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Reagent (20 μL/well) was added to the wells and the plate was incubated at 37°C with a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air for 1 hr. MTS formazan product was measured by determining the absorbance of aliquots (100 μL) with a 490 nm test wavelength using a 96-well plate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Western blot analysis for phosphorylated p44/42 MAPK, p38 and JNK

LPS-treated and control BMECs were washed three times with ice-cold phosphate buffered saline containing 1 mM Na3VO4. Cells were scraped and lysed in phosphoprotein lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) containing 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) and briefly sonicated. Cell lysates were centrifuged (15,000 × g at 4°C for 15 min) and the supernatants were stored at −80°C until use. The protein concentration of each sample was determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Twenty μg of the total protein was mixed with NuPAGE® LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen) and incubated for 3 min at 100°C. Proteins were separated on NuPAGE® Novex 4–12% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen) and then transferred to an nitrocellulose membrane (Invitrogen). After transfer, the blots were blocked with 5% BSA/Tris-buffered saline (TBS: 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl) overnight at 4°C. The membrane was incubated with the primary antibody diluted in 0.1% BSA/TBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (TBS-T) for 2 hr at room temperature. The phosphorylation of p44/42 MAPK, p38 MAPK and JNK were detected using anti-Active® MAPK (1:5000), anti-Active® p38 (1:2000) and anti-Active® JNK (1:5000) polyclonal antibodies, respectively (all purchased from Promega). Blots were washed and incubated with peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) diluted in 0.1% BSA/TBS-T for 1 hr at room temperature. The immunoreactive bands were visualized on an X-ray film (Kodak) using SuperSignal® West Pico chemiluminescent substrate kit (Pierce). To reprobe total p44/42 MAPK, p38 MAPK and JNK, the membrane was incubated in stripping buffer (0.2 M glycine, 0.1% SDS and 1% Tween 20, pH 2.2) for 15 min twice and blocked with 5% non-fat milk/TBS-T. The total p44/42 MAPK, p38 MAPK and JNK were detected using anti-p44/42 MAPK (1:1000), p38 MAPK (1:1000) and JNK (1:1000) antibodies, respectively (all purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA).

Statistical analysis

Values are expressed as means ± SEM. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s or Tukey-Kramer’s test were applied to multiple comparisons. The differences between means were considered to be significant when P values were less than 0.05 using Prism 5.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA).

Results

LPS increases HIV-1 transport across BMECs

To determine whether LPS could induce the increase of HIV transport across the BBB, LPS was added into the luminal side of BMEC monolayer cultures. A 4-hr exposure of BMECs to LPS at 1, 10, and 100 μg/mL dose-dependently increased the permeability coefficient for 131I-HIV by 15.0, 26.7 and 80.0%, respectively (Fig. 1A). LPS at the concentration of 100 μg/mL increased the permeability coefficient for 131I-HIV by 6.9 to 37.3% during 0.5 to 4 hr exposure (Fig. 1C). To determine whether LPS could disrupt the integrity of the tight junctions, TEER was measured. LPS decreased TEER dose- and time-dependently (Fig. 1B and 1D). A 4 hr exposure of BMECs to LPS at 1, 10, and 100 μg/mL reduced TEER to 35.2, 33.4, and 27.3 Ω × cm2, respectively (Fig. 1B). Similarly, TEER was decreased to 39.6, 45.3, and 32.5 Ω × cm2 by 0.5 to 4 hr exposure to LPS at 100 μg/mL (Fig. 1D). The MTS assay showed that LPS did not change the viability of BMECs after a 4 hr exposure to LPS (100 μg/mL) (data not shown). This indicated that although LPS increased HIV transport and disrupted tight junction integrity, these events were not caused by the cytotoxicity of LPS to BMECs. In all subsequent studies, BMEC monolayers were treated with 100 μg/mL LPS for 4 hr.

Figure 1.

Effect of LPS on the permeability of BMECs to 131I-HIV-1 (A and C) and TEER (B and D). In panels A and B, BMECs were treated with LPS for 4 hr. In panels C and D, BMECs were treated with 100 μg/mL LPS. In panels A and C, results are expressed as % of control. Control values were 5.24 ± 0.71 × 10−5 and 1.75 ± 0.07 × 10−5 cm/min (A and C, respectively). Values are means ± SEM (n = 4–9). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, significant differences from control.

Effects of various inhibitors of soluble factors induced by LPS on LPS-increased HIV transport across BMECs

To determine whether inflammatory mediators produced the LPS-induced increase in HIV transport across BMECs, indomethacin (COX inhibitor; 1 and 5 μM), L-NAME (NOS inhibitor; 1 and 3 mM) and pentoxifylline (TNF-α inhibitor; 0.2 and 2 mM) were incubated with LPS. All three inhibitors failed to inhibit the increase in HIV permeability for BMEC monolayers treated with LPS (Fig. 2A–C). By contrast, pentoxifylline (2 mM) attenuated the decrease in TEER induced by LPS, and resulting in a 32% inhibition of the LPS-induced decrease in TEER (Fig. 2F, P < 0.05 vs. LPS). Indomethacin and L-NAME did not inhibit LPS-induced decrease in TEER (Fig. 2D and E).

Figure 2.

Effects of indomethacin, L-NAME, and pentoxifylline on the LPS-induced increase in permeability of 131I-HIV-1 to BMECs (A, C, and E) and the LPS-induced decrease in TEER (B, D, and F). BMECs were treated with LPS (100 μg/mL) for 4 hr in the presence or absence of indomethacin (1, 5 μM; A and B), L-NAME (1, 3 mM; C and D), or pentoxifylline (0.2, 2 mM; E and F). In panels A, C, and E, results are expressed as % of control. The control values of permeability coefficient for 131I-HIV-1 in panel A, C, and E were 2.90 ± 0.44 × 10−5, 2.83 ± 0.44 × 10−5, and 1.28 ± 0.09 × 10−5 cm/min, respectively. Values are means ± SEM (n = 6–21). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, significant difference from control. #P < 0.05, significant difference from LPS (100 μg/mL).

Effects of various MAPK inhibitors on LPS-induced increase in HIV-1 transport across BMECs

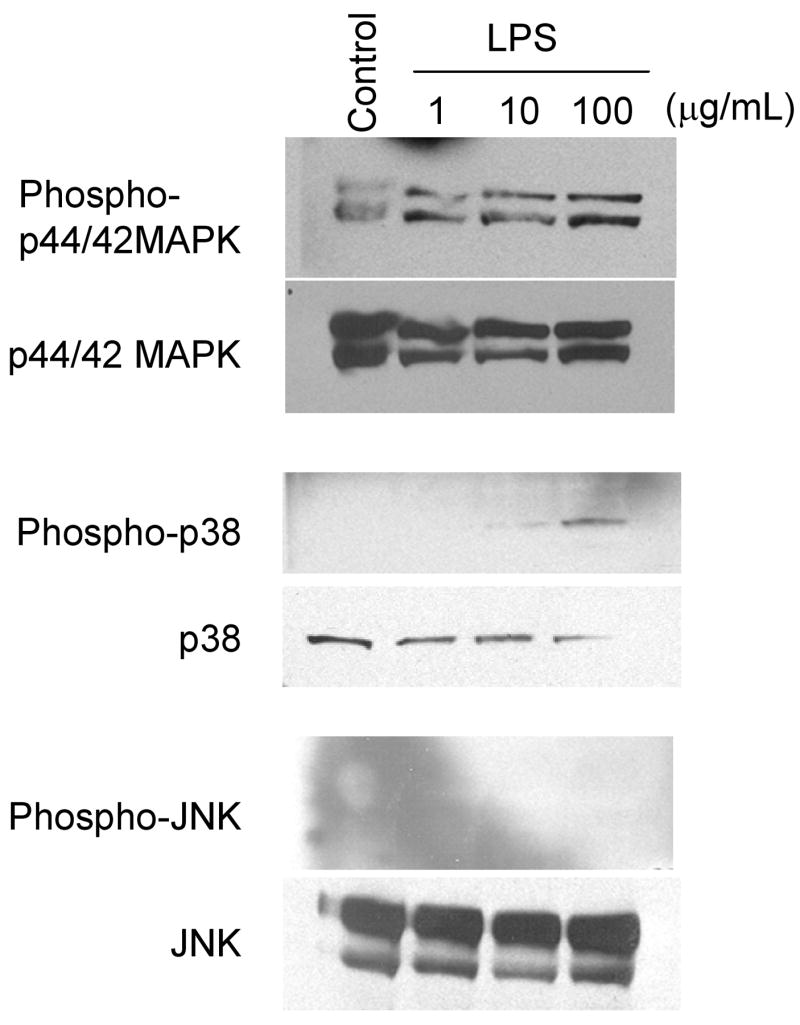

To determine whether LPS could activate MAPK pathways and then increase HIV transport across BMECs, the cells were treated with LPS in the presence of various inhibitors, U0126 (5–20 μM; p44/42 MAPK inhibitor), SB203580 (1–10 μM; p38 MAPK inhibitor) and SP600125 (5–20 μM; JNK inhibitor), respectively. In addition, the increases of phosphorylation of MAPKs were detected by Western blot analysis. U0126 (5–20 μM) did not affect the LPS-induced increase in 131I-HIV transport (Fig. 3A), but 20 μM of U0126 did significantly attenuated the decrease in TEER induced by LPS by 40% (P < 0.05 vs. LPS) (Fig. 3B). SB203580 (10 μM) significantly decreased the LPS-induced increase in permeability for 131I-HIV to 124.6% of control (P < 0.05 vs. LPS) (Fig. 3C), whereas SB203580 did not inhibit the decrease in TEER induced by LPS (Fig. 3D). SP600125 did not change either the increase in 131I-HIV transport or the decrease in TEER induced by LPS (Fig. 3E and 3F, respectively). As shown in Fig. 4, LPS dose-dependently increased phoshorylation of p44/42 MAPK and p38 MAPK in BMECs, but did not that of JNK. As positive control for phospho-JNK, we confirmed that phosphorylation of JNK was induced in sorbitol-treated PC12 cells (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Effects of various MAPK inhibitors on the LPS-induced increase in permeability of 131I-HIV-1 to BMECs (A, C, and E) and the LPS-induced decrease in TEER (B, D, and F). BMECs were treated with LPS (100 μg/mL) for 4 hr in the presence or absence of U0126 (5–20 μM; A and B), SB203580 (1–10 μM; C and D), or SP600125 (5–20 μM; E and F). In panels A, C, and E, results are expressed as % of control. The control values of permeability coefficient for 131I-HIV-1 in panel A, C, and E were 1.47 ± 0.19 × 10−5, 2.04 ± 0.35 × 10−5, and 1.24 ± 0.91 × 10−5 cm/min, respectively. Values are means ± SEM (n = 3–18). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, significant difference from control. #P < 0.05, significant difference from LPS (100 μg/mL).

Figure 4.

LPS increased phosphorylation of MAPKs in BMECs. BMECs were treated with LPS (1, 10 and 100 μg/mL) for 4 hr. Western blot analyses were performed to detect phosphorylated p44/42 MAPK, p38 MAPK and JNK as well as total p44/42 MAPK, p38 MAPK and JNK. Photographs are representative in three independent experiments.

Discussion

In the present study, we used noninfective cell-free HIV-1 inactivated by aldrithiol-2 and a monolayer of primary mouse brain endothelial cells to investigate the mechanism of HIV-1 transport across the BBB as reported previously (Banks et al., 2004; Nakaoke et al., 2005). This virus retains conformational and functional integrity of envelope proteins (Rossio et al., 1998) and radiolabeling of virus by chloramine T method can preserve the viral coat glycoprotein activity (Frost, 1977; Montelaro and Rueckert, 1975). Infectious HIV-1 penetrated the BBB without productive replication in brain endothelial cells (Liu et al., 2002), suggesting that the ability of infection is independent of BBB permeability of cell-free HIV-1. We assessed the properties of BMEC monolayer as BBB model by measuring TEER, permeability to albumin, and expression of tight junction associated proteins. In our in vitro BBB model (non-treated), TEER and permeability coefficient of albumin were 52–75 Ω × cm2 and less than 1 × 10−5 cm/min, respectively. Occludin, claudin-5, and ZO-1 were expressed (data not shown). Although the TEER value is slightly lower than that of brain endothelial cells isolated from other species, such as human, bovine, porcine, and rat (Deli et al., 2005), the permeability to albumin is as low as bovine brain endothelial cells (Plateel, et al., 1997). The BMEC monolayer used in this study showed a similar permeability coefficient of HIV-1 (1.2–5.2 × 10−5 cm/min) compared with our previous study in vivo (3.3 × 10−5 cm/min when surface area of brain microvessel is 100 cm2/g brain) (Banks et al., 2004). Therefore, the use of this virus and BMEC monolayer is suitable for the purposes of the present study.

Bacterial LPS dose- and time-dependently increased the permeability of BMECs to HIV-1 and decreased TEER values of BMECs (Fig. 1). TEER indicates the integrity of tight junctions in this model. LPS can enhance HIV-1 transport across the BBB and disrupt the integrity of tight junction through direct action at the BBB. These effects of LPS were evident after 4 hr treatment of LPS at the concentration of 100 μg/mL. In this condition, LPS was not cytotoxic to the BMECs. Therefore, this disruption was not caused by the damage to the BMECs by LPS. Previous in vitro studies demonstrated that LPS increases paracellular permeability of brain endothelial cells and decreases TEER (Tunkel et al., 1991; de Vries et al., 1996; Descamps et al., 2003; Boveri et al., 2006; Veszelka et al., 2007). An in vivo study showed that LPS facilitated transport of gp120 by enhancement of adsorptive endocytosis and disruption of the BBB (Banks et al., 1999). The findings here suggest that LPS increased HIV-1 transport across BBB primarily through transcytotic mechanisms.

Since LPS induces the release of prostaglandin E2, NO, and several cytokines including TNF-α by brain endothelial cells, we examined whether the LPS-induced increase in HIV-1 transport was mediated by these inflammatory mediators. The enhanced permeability of the BBB to HIV-1 and decreased TEER induced by LPS were not inhibited by indomethacin or L-NAME (Fig. 2), In the presence of pentoxifylline, LPS-induced increase in HIV-1 transport was not inhibited, although pentoxifylline attenuated the LPS-induced decrease in TEER (Fig. 2). These results indicated that LPS increased HIV-1 transport across the BBB independently of prostaglandins, NO, and TNF-α, while LPS decreased TEER through a TNF-α dependent pathway. Moreover, these results would suggest that LPS increased HIV-1 transport across BBB mainly through a transcellular pathway, such as adsorptive endocytosis. Pentoxifylline, a general phosphodiesterase inhibitor, is known to have anti-inflammatory properties and inhibits the production of TNF-α (Strieter et al., 1988). Phosphodiesterase inhibitors prevent the hydrolysis of intracellular cAMP, which increases TEER and reduces paracellular permeability of the BBB (Deli et al., 1995). Therefore, the effect of pentoxifylline likely involved the inhibition of TNF-α production by BMECs and/or the increase in intracellular cAMP level in BMECs.

Besides TNF-α, LPS induces the release of several other cytokines by BMECs, such as IL-6. In addition, IL-6 and LPS activate MAPK signaling pathways through their receptors. The phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and JNK is induced by inflammatory cytokines and various stresses. The activation of p44/42 MAPK signaling is involved in HIV-1 entry to brain endothelial cells (Liu et al., 2002). We next determined whether MAPK signaling pathways were involved in LPS-enhanced HIV-1 transport by using inhibitors of MAPK kinase (MEK) 1/2 (U0126), p38 MAPK (SB203580), and JNK (SP600125). U0126 inhibits the phosphorylation of MEK1/2, which is up stream of p44/42 MAPK. Although U0126 significantly inhibited the decrease in TEER induced by LPS, HIV-1 transport was not affected (Fig. 3A and 3B). SB203580 significantly decreased the LPS-induced increase HIV-1 permeability without affecting TEER (Fig. 3C and 3D). SP600125 had no effects on the changes in HIV-1 permeability and TEER induced by LPS (Fig. 3E and 3F). In parallel, LPS dose-dependently increased the phosphorylation of p44/42 MAPK and p38 MAPK but not that of JNK in BMECs (Fig. 4). These results showed that the activation of p44/42 MAPK and p38 MAPK by LPS induced the decrease in TEER and the increase in HIV-1 transport, respectively. In addition, the p38 MAPK signaling pathway would mainly contribute to the enhanced transcellular transport of HIV-1 by LPS. The role of p44/42 MAPK in regulation of BBB paracellular permeability has been controversial. The inhibition of mannitol-induced activation of p44/42 MAPK in brain endothelial cells did not alter paracellular permeability of sucrose (Miller et al., 2005). HIV-1 Tat alters claudin-5 and ZO-1 expression in brain endothelial cells through p44/42 MAPK activation (András et al., 2005; Pu et al., 2005). The regulation of paracellular permeability by p44/42 MAPK activation may be dependent on the stimulators (extracellular signals) and/or involved in other signaling pathways. SB203580 did not alter the basal permeability of BBB to HIV-1 (data not shown). The activation of the p38 MAPK pathway leads to the production and release of several cytokines (Dong et al., 2002). Probably, the production of these cytokines is regulated by p38 MAPK, which in turn may induce the increased transcellular transport of HIV-1 by LPS.

Figure 5 shows the diagram of the possible mechanisms by which LPS increased HIV-1 transport across BBB. The question of how LPS increases the phosphorylation of p44/42 MAPK and p38 MAPK is raised. The two likely mechanisms by which LPS induced the activation of p44/42 MAPK and p38 MAPK signaling are (i) LPS acts directly through TLRs or (ii) soluble factors induced by LPS activate their receptors. MAPKs are key elements in the TLR signaling pathway (Akira and Takeda, 2004). LPS induces the release of GM-CSF, IL-6, and TNF-α from BMECs (Verma et al., 2006). These cytokines are known to activate MAPKs signaling (Heinrich et al., 2003; Miller et al., 2005; Okuda et al., 1992). Since pentoxifylline and U0126 attenuated the LPS-induced decrease in TEER, the activation of p44/42 MAPK, which may be caused by TNF-α(Miller et al., 2005), contributes to the disruption of tight junctions through affecting the expression of tight junction associated proteins. The activation of p38 MAPK mediates transcellular transport of HIV-1 across the BBB. In addition, p38 MAPK can up-regulate expression of inflammatory cytokines, which might increase the transcellular transport of HIV-1.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the mechanisms by which LPS induced the activation of MAPKs followed by the increase in the BBB permeability through paracellular and transcelluar routes. LPS-increased HIV-1 transport is mainly dependent on transcellular route. Dashed lines indicate possible intermediate steps.

Although highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) dramatically decreased the incidence and severity of HIV-associated dementia, prevalence of HAD including minor cognitive motor disorder is increasing with the longer lifespan of HIV patients with HAART (González-Scarano and Martín-García, 2005). Recent concern about the consequences of HAD has emerged with the increasing resistance to antiretroviral drugs. With introduction of HAART, therefore, the patients on HAART with a slowly progressive dementia and incomplete virological control have been proposed (McArthur et al., 2003). Recently, Brenchley et al. reported that plasma LPS levels are still higher in chronic HIV-infected patients with HAART than in the uninfected (Brenchley et al., 2006). Furthermore, HAART is often started when immune suppression first manifests. Immune suppression would easily lead to opportunistic infections. Taken together, our results suggested that bacterial infection might be a risk factor for the development of HIV-associated neurological impairments in HIV patients with HAART or pre-HAART treatment.

In conclusion, we found that LPS-increased HIV-1 transport across the BBB through transcytotic pathway was dependent on p38 MAPK signaling but independent on prostaglandins, NO, TNF-α or p44/42 MAPK signaling. This LPS-increased HIV-1 transport was mainly dependent on transcellular route because inhibition of p38 MAPK by SB203580 attenuated the LPS-increased HIV-1 transport without affecting the LPS-induced reduction in TEER. Interestingly, our results indicated that the recovery of LPS-decreased TEER by pentoxifylline and U0126 did not help to inhibit the LPS-increased HIV-1 transport. These results suggest that the inhibition of the transcellular route is important in preventing the invasion of cell-free HIV-1 to the CNS rather than that of the paracellular route increased by disruption of tight junctions. Considering the possibility that p38 MAPK could be activated by blood-borne inflammatory mediators, our results suggest that the p38 MAPK signaling pathway would mediate the enhancement of transcellular transport of HIV-1 across the BBB in the systemic inflammatory state and/or bacterial infection.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Melissa Fleegal-DeMotta (VA Medical Center-St.Louis and Saint Louis University School of Medicine) for support with cell culture and Western blot analysis and Dr. Mária A. Deli (Institute of Biophysics, Biological Research Centre of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences) for technical advice on primary brain endothelial cell culture. Funded in part with Federal funds from National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under Contract No. N01-CO-12400. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of names, commercial products, or organization imply endorsement by the U.S. government. Supported by VA Merit Review and NIH R01NS050547. The virus was a kind gift the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signaling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso K, Pontiggia P, Medenica R, Rizzo S. Cytokine patterns in adults with AIDS. Immunol Invest. 1997;26:341–350. doi: 10.3109/08820139709022691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- András IE, Pu H, Deli MA, Nath A, Hennig B, Toborek M. HIV-1 Tat protein alters tight junction protein expression and distribution in cultured brain endothelial cells. J Neurosci Res. 2003;74:255–265. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- András IE, Pu H, Tian J, Deli MA, Nath A, Hennig B, Toborek M. Signaling mechanisms of HIV-1 Tat-induced alterations of claudin-5 expression in brain endothelial cells. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:1159–1170. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA, Akerstrom V, Kastin AJ. Adsorptive endocytosis mediates the passage of HIV-1 across the blood-brain barrier: evidence for a post-internalization coreceptor. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:533–540. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA, Freed EO, Wolf KM, Robinson SM, Franko M, Kumar VB. Transport of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 pseudoviruses across the blood-brain barrier: Role of envelop proteins and adsorptive endocytosis. J Virol. 2001;75:4681–4691. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.10.4681-4691.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA, Kastin AJ. Characterization of lectin-mediated brain uptake of HIV-1 gp120. J Neurosci Res. 1998;54:522–529. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19981115)54:4<522::AID-JNR9>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA, Kastin AJ, Akerstrom V. HIV-1 protein gp120 crosses the blood-brain barrier: role of adosorptive endocytosis. Life Sci. 1997;61:PL119–PL125. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00597-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA, Kastin AJ, Brennan JM, Vallance KL. Adsorptive endocytosis of HIV-1 gp120 by blood-brain barrier is enhanced by lipopolysaccharide. Exp Neurol. 1999;156:165–171. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.7011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA, Robinson SM, Wolf KM, Bess JW, Jr, Arthur LO. Binding, internalization, and membrane incorporation of human immunodeficiency virus-1 at the blood-brain barrier is differentially regulated. Neuroscience. 2004;128:143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard A, Montagnier L, Gougeon ML. Influence of microbial infections on the progression of HIV disease. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:326–331. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW, Asher TE, Silvestri G, Rao S, Kazzaz Z, Bornstein E, Lambotte O, Altmann D, Blazar BR, Rodriguez B, Teixeira-Johnson L, Landay A, Martin JN, Hecht FM, Picker LJ, Lederman MM, Deeks SG, Douek DC. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat Med. 2006;12:1365–1371. doi: 10.1038/nm1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boveri M, Kinsner A, Berezowski V, Lenfant AM, Draing C, Cecchelli R, Dehouck MP, Hartung T, Prieto P, Bal-Price A. Highly purified lipoteichoic acid from gram-positive bacteria induced in vitro blood-brain barrier disruption through glia activation: role of proinflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide. Neuroscinece. 2006;137:1193–1209. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis LE, Hjelle BL, Miller VE, Palmer DL, Llewellyn AL, Merlin TL, Young SA, Mills RG, Wachsman W, Wiley CA. Early viral brain invasion in iatrogenic human immunodeficiency virus infection. Neurology. 1992;42:1736–1739. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.9.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehouck MP, Jolliet-Riant P, Brée F, Fruchart JC, Cecchelli R, Tillement JP. Drug transfer across the blood-brain barrier: correlation between in vitro and in vivo models. J Neurochem. 1992;58:1790–1797. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb10055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deli MA, Ábrahám CS, Kataoka Y, Niwa M. Permeability studies on in vitro blood-brain barrier models: physiology, pathology, and pharmacology. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2005;25:59–127. doi: 10.1007/s10571-004-1377-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deli MA, Dehouck MP, Abrahám CS, Cecchelli R, Joó F. Penetration of small molecular weight substances through cultured bovine brain capillary endothelial cell monolayers: the early effects of cyclic adenosine 3’,5’-monophosphate. Exp Physiol. 1995;80:675–678. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1995.sp003877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descamps L, Coisne C, Dehouck B, Cecchelli R, Torpier G. Protective effect of glial cells against lipopolysaccharide-mediated blood-brain barrier injury. Glia. 2003;42:46–58. doi: 10.1002/glia.10205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries HE, Blom-Roosemalen MC, de Boer AG, van Berkel TJ, Breimer DD, Kuiper J. Effect of endotoxin on permeability of bovine cerebral endothelial cell layers in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;277:1418–1423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries HE, Hoogendoorn KH, van Dijk J, Zijlstra FJ, van Dam AM, Breimer DD, van Berkel TJ, de Boer AG, Kuiper J. Eicosanoid production by rat cerebral endothelial cells: stimulation by lipopolysaccharide, interleukin-1 and interleukin-6. J Neuroimmuol. 1995;59:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(95)00009-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didier N, Banks WA, Créminon C, Dereuddre-Bosquet N, Mabondzo A. HIV-1-induced production of endothelin-1 in an in vitro model of the human blood-brain barrier. Neuroreport. 2002;13:1179–1183. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200207020-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong C, Davis RJ, Flavell RA. MAP kinase in the immune response. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:55–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.091301.131133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Equils O, Faure E, Thomas L, Bulut Y, Trushin S, Arditi M. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide activates HIV long terminal repeat through Toll-like receptor 4. J Immunol. 2001;166:2342–2347. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiala M, Looney DJ, Stins M, Way DD, Zhang J, Gan X, Chiappelli F, Schweitzer ES, Shapshak P, Weinand M, Graves MC, Witte M, Kim KS. TNF-α opens a paracellular route for HIV-1 invasion across the blood-brain barrier. Mol Med. 1997;3:553–564. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost HE. Radioactive labelling of viruses: an iodination preserving biological properties. J Gen Virol. 1977;35:181–185. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-35-1-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartner S. HIV infection and dementia. Science. 2000;287:602–604. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Scarano F, Martín-García J. The neuropathogenesis of AIDS. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:69–81. doi: 10.1038/nri1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich PC, Behrmann I, Haan S, Hermanns HM, Müller-Newen G, Schaper F. Principles of interleukin (IL)-6 cytokine signaling and its regulation. Biochem J. 2003;374:1–20. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hittinger G, Poggi C, Delbeke E, Profizi N, Lafeuillade A. Correlation between plasma levels of cytokines and HIV-1 RNA copy number in HIV-infected patients. Infection. 1998;26:100–103. doi: 10.1007/BF02767768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanmogne GD, Primeaux C, Grammas P. HIV-1 gp120 proteins alter tight junction protein expression and brain endothelial cell permeability: implications for the pathogenesis of HIV-associated dementia. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64:498–505. doi: 10.1093/jnen/64.6.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu NQ, Lossinsky AS, Popik W, Li X, Gujuluva C, Kriederman B, Roberts J, Pushkarsky T, Burkrinsky M, Witte M, Weinand M, Fiala M. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 enters brain microvascular endothelia by macropinocytosis dependent on lipid rafts and the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. J Virol. 2002;76:6689–6700. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.13.6689-6700.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur JC, Haughey N, Gartner S, Conant K, Pardo C, Nath A, Sacktor N. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated dementia: An evolving disease. J Neurovirol. 2003;9:205–221. doi: 10.1080/13550280390194109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller F, Fenart L, Landry V, Coisne C, Cecchelli R, Dehouck MP, Buée-Scherrer V. The MAP kinase pathway mediates transcytosis induced by TNF-α in an in vitro blood-brain barrier model. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:835–844. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montelaro RC, Rueckert RR. On the use of chloramine-T to iodinate specifically the surface proteins of intact enveloped viruses. J Gen Virol. 1975;29:127–131. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-29-1-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses AV, Bloom FE, Pauza CD, Nelson JA. Human immunodeficiency virus infection of human brain capillary endothelial cells occurs via a CD4/galactosylceamide-independent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10474–10478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaoke R, Ryerse JS, Niwa M, Banks WA. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transport across the in vitro mouse brain endothelial cell monolayer. Exp Neurol. 2005;193:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nottet HSLM. The blood-brain barrier: monocyte and viral entry into the brain. In: Gendelman HE, Grant I, Everall IP, Lipton SA, Swindells S, editors. The Neurology of AIDS. 2. Oxford University Press; New York: 2005. pp. 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Okuda K, Sanghera JS, Pelech SL, Kanakura Y, Hallek M, Griffin JD, Druker BJ. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, interleukin-3, and steel factor induce rapid tyrosine phosphorylation of p42 and p44 MAP kinase. Blood. 1992;79:2880–2887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrière N, Demeuse P, Garcia E, Regina A, Debray M, Andreux JP, Couvreur P, Scherrmann JM, Temsamani J, Couraud PO, Deli MA, Roux F. Puromycin-based purification of rat brain capillary endothelial cell cultures. Effect on the expression of blood-brain barrier-specific properties. J Neurochem. 2005;93:279–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.03020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persidsky Y, Stins M, Way D, Witte MH, Weinand M, Kim KS, Bock P, Gendelman HE, Fiala M. A model for monocyte migration through the blood-brain barrier during HIV-1 encephalitis. J Immunol. 1997;158:3499–3510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plateel M, Teissier E, Cecchelli R. Hypoxia dramatically increases the nonspecific transport of blood-borne proteins to the brain. J Neurochem. 1997;68:874–877. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68020874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power C, Kong PA, Crawford TO, Wesselingh S, Glass JD, McArthur JC, Trapp BD. Cerebral white matter changes in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome dementia: alterations of the blood-brain barrier. Ann Neurol. 1993;34:339–350. doi: 10.1002/ana.410340307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price TO, Uras F, Banks WA, Ercal N. A novel antioxidant N-acetylcysteine amide prevents gp120- and Tat-induced oxidative stress in brain endothelial cells. Exp Neurol. 2006;201:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu H, Tian J, András IE, Hayashi K, Flora G, Hennig B, Toborek M. HIV-1 Tat protein-induced alterations of ZO-1 expression are mediated by redox-regulated ERK 1/2 activation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:1325–1335. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossio JL, Esser MT, Suryanarayana K, Schneider DK, Bess JW, Jr, Vasquez GM, Wiltrout TA, Chertova E, Grimes MK, Sattentau Q, Arthur LO, Henderson LE, Lifson JD. Inactivation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity with preservation of conformational and functional integrity of virion surface proteins. J Virol. 1998;72:7992–8001. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.7992-8001.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AK, Jiang Y. How does peripheral lipopolysaccharide induce gene expression in the brain of rats? Toxicology. 2004;201:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strieter RM, Remick DG, Ward PA, Spengler RN, Lynch JP, 3rd, Larrick J, Kunkel SL. Cellular and molecular regulation of tumor necrosis factor-α production by pentoxifylline. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;155:1230–1236. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)81271-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabó CA, Deli MA, Ngo TKD, Joó F. Production of pure primary rat cerebral endothelial cell culture: a comparison of different methods. Neurobiology. 1997;5:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunkel AR, Rosser SW, Hansen EJ, Scheld WM. Blood-brain barrier alterations in bacterial meningitis: development of an in vitro model and observations on the effects of lipopolysaccharide. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1991;27A:113–120. doi: 10.1007/BF02630996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma S, Nakaoke R, Dohgu S, Banks WA. Release of cytokines by brain endothelial cells: A polarized response to lipopolysaccharide. Brain Behav Immun. 2006;20:449–455. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veszelka S, Pásztói M, Farkas AE, Krizbai I, Ngo TK, Niwa M, Abrahám CS, Deli MA. Pentosan polysulfate protects brain endothelial cells against bacterial lipopolysaccharide-induced damages. Neurochem Int. 2007;50:219–228. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]